|

|

||

| Kellscraft

Studio Home Page |

Wallpaper

Images for your Computer |

Nekrassoff Informational Pages |

Web

Text-ures© Free Books on-line |

|

Celtic Fairy Tales Selected and

Edited By Joseph Jacobs Editor of

"Folk Lore" Illustrated

by John D.

Batten

London David Nutt.

270 Strand 1892

TO ALFRED

NUTT PREFACE

In making

my selection I have chiefly tried to make the stories characteristic.

It would have

been easy, especially from Kennedy, to have made up a volume entirely

filled with

"Grimm's Goblins" à la Celtique. But one can have too much even

of that very good thing, and I have therefore avoided as far as

possible the more

familiar "formulae" of folk-tale literature. To do this I had to

withdraw

from the English-speaking Pale both in Scotland and Ireland, and I laid

down the

rule to include only tales that have been taken down from Celtic

peasants ignorant

of English. Having

laid down the rule, I immediately proceeded to break it. The success of

a fairy

book, I am convinced, depends on the due admixture of the comic and the

romantic:

Grimm and Asbjörnsen knew this secret, and they alone. But the Celtic

peasant who

speaks Gaelic takes the pleasure of telling tales somewhat sadly: so

far as he has

been printed and translated, I found him, to my surprise, conspicuously

lacking

in humour. For the comic relief of this volume I have therefore had to

turn mainly

to the Irish peasant of the Pale; and what richer source could I draw

from? For the

more romantic tales I have depended on the Gaelic, and, as I know about

as much

of Gaelic as an Irish Nationalist M. P., I have had to depend on

translators. But

I have felt myself more at liberty than the translators themselves, who

have generally

been over-literal, in changing, excising, or modifying the original. I

have even

gone further. In order that the tales should be characteristically

Celtic, I have

paid more particular attention to tales that are to be found on both

sides of the

North Channel. In

re-telling

them I have had no scruple in interpolating now and then a Scotch

incident into

an Irish variant of the same story, or vice versa. Where the

translators

appealed to English folklorists and scholars, I am trying to attract

English children.

They translated; I endeavoured to transfer. In short, I have tried to

put myself

into the position of an ollamh or sheenachie familiar

with both forms

of Gaelic, and anxious to put his stories in the best way to attract

English children.

I trust I shall be forgiven by Celtic scholars for the changes I have

had to make

to effect this end. The stories

collected in this volume are longer and more detailed than the English

ones I brought

together last Christmas. The romantic ones are certainly more romantic,

and the

comic ones perhaps more comic, though there may be room for a

difference of opinion

on this latter point. This superiority of the Celtic folk-tales is due

as much to

the conditions under which they have been collected, as to any innate

superiority

of the folk-imagination. The folk-tale in England is in the last stages

of exhaustion.

The Celtic folk-tales have been collected while the practice of

story-telling is

still in full vigour, though there are every signs that its term of

life is already

numbered. The more the reason why they should be collected and put on

record while

there is yet time. On the whole, the industry of the collectors of

Celtic folk-lore

is to be commended, as may be seen from the survey of it I have

prefixed to the

Notes and References at the end of the volume. Among these, I would

call attention

to the study of the legend of Beth Gellert, the origin of which, I

believe, I have

settled. While

I have endeavoured to render the language of the tales simple and free

from bookish

artifice, I have not felt at liberty to retell the tales in the English

way. I have

not scrupled to retain a Celtic turn of speech, and here and there a

Celtic word,

which I have not explained within brackets — a practice to be

abhorred of

all good men. A few words unknown to the reader only add effectiveness

and local

colour to a narrative, as Mr. Kipling well knows. One

characteristic

of the Celtic folk-lore I have endeavoured to represent in my

selection, because

it is nearly unique at the present day in Europe. Nowhere else is there

so large

and consistent a body of oral tradition about the national and mythical

heroes as

amongst the Gaels. Only the byline, or hero-songs of Russia,

equal in extent

the amount of knowledge about the heroes of the past that still exists

among the

Gaelic-speaking peasantry of Scotland and Ireland. And the Irish tales

and ballads

have this peculiarity, that some of them have been extant, and can be

traced, for

well nigh a thousand years. I have selected as a specimen of this class

the Story

of Deirdre, collected among the Scotch peasantry a few years ago, into

which I have

been able to insert a passage taken from an Irish vellum of the twelfth

century.

I could have more than filled this volume with similar oral traditions

about Finn

(the Fingal of Macpherson's "Ossian"). But the story of Finn, as told

by the Gaelic peasantry of to-day, deserves a volume by itself, while

the adventures

of the Ultonian hero, Cuchulain, could easily fill another. I have

endeavoured to include in this volume the best and most typical stories

told by

the chief masters of the Celtic folk-tale, Campbell, Kennedy, Hyde, and

Curtin,

and to these I have added the best tales scattered elsewhere. By this

means I hope

I have put together a volume, containing both the best, and the best

known folk-tales

of the Celts. I have only been enabled to do this by the courtesy of

those who owned

the copyright of these stories. Lady Wilde has kindly granted me the

use of her

effective version of "The Horned Women;" and I have specially to thank

Messrs. Macmillan for right to use Kennedy's "Legendary Fictions," and

Messrs. Sampson Low & Co., for the use of Mr. Curtin's Tales. In making

my selection, and in all doubtful points of treatment, I have had

resource to the

wide knowledge of my friend Mr. Alfred Nutt in all branches of Celtic

folk-lore.

If this volume does anything to represent to English children the

vision and colour,

the magic and charm, of the Celtic folk-imagination, this is due in

large measure

to the care with which Mr. Nutt has watched its inception and progress.

With him

by my side I could venture into regions where the non-Celt wanders at

his own risk. Lastly,

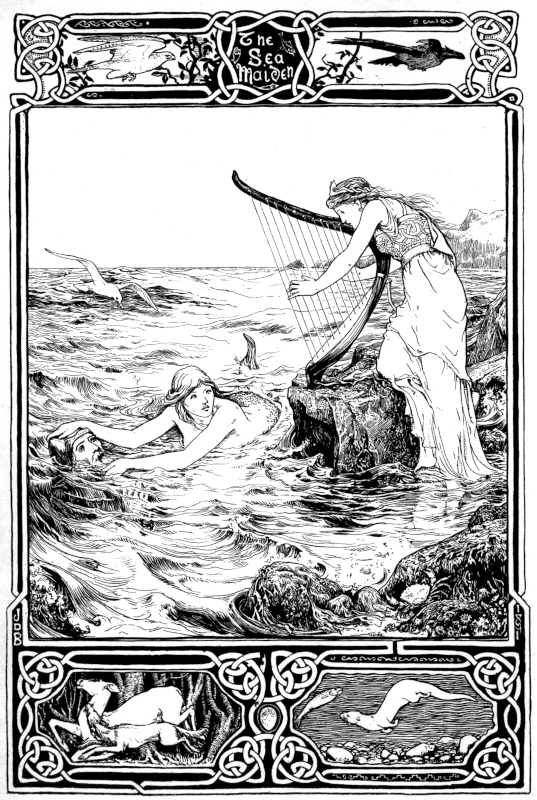

I have again to rejoice in the co-operation of my friend, Mr. J. D.

Batten, in giving

form to the creations of the folk-fancy. He has endeavoured in his

illustrations

to retain as much as possible of Celtic ornamentation; for all details

of Celtic

archaeology he has authority. Yet both he and I have striven to give

Celtic things

as they appear to, and attract, the English mind, rather than attempt

the hopeless

task of representing them as they are to Celts. The fate of the Celt in

the British

Empire bids fair to resemble that of the Greeks among the Romans. "They

went

forth to battle, but they always fell," yet the captive Celt has

enslaved his

captor in the realm of imagination. The present volume attempts to

begin the pleasant

captivity from the earliest years. If it could succeed in giving a

common fund of

imaginative wealth to the Celtic and the Saxon children of these isles,

it might

do more for a true union of hearts than all your politics. JOSEPH

JACOBS. Contents Connla and the Fairy Maiden Guleesh The Field of Boliauns The Horned Women Conall Yellowclaw Hudden and Dudden and Donald O'Neary The Shepherd of Myddvai The Sprightly Tailor The Story of Deirdre Munachar and Manachar Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree King O'Toole and his Goose The Wooing of Olwen Jack and his Comrades The Shee an Gannon and the Gruagach Gaire The Story-Teller at Fault The Sea-Maiden A Legend of Knockmany Fair, Brown, and Trembling Jack and His Master Beth Gellert The Tale of Ivan Andrew Coffey The Battle of the Birds Brewery of Eggshells The Lad with the Goat-Skin Notes and References |

ast year, in giving the

young ones a

volume of English Fairy Tales, my difficulty was one of collection.

This time, in

offering them specimens of the rich folk-fancy of the Celts of these

islands, my

trouble has rather been one of selection. Ireland began to collect her

folk-tales

almost as early as any country in Europe, and Croker has found a whole

school of

successors in Carleton, Griffin, Kennedy, Curtin, and Douglas Hyde.

Scotland had

the great name of Campbell, and has still efficient followers in

MacDougall, MacInnes,

Carmichael, Macleod, and Campbell of Tiree. Gallant little Wales has no

name to

rank alongside these; in this department the Cymru have shown less

vigour than the

Gaedhel. Perhaps the Eisteddfod, by offering prizes for the collection

of Welsh

folk-tales, may remove this inferiority. Meanwhile Wales must be

content to be somewhat

scantily represented among the Fairy Tales of the Celts, while the

extinct Cornish

tongue has only contributed one tale.

ast year, in giving the

young ones a

volume of English Fairy Tales, my difficulty was one of collection.

This time, in

offering them specimens of the rich folk-fancy of the Celts of these

islands, my

trouble has rather been one of selection. Ireland began to collect her

folk-tales

almost as early as any country in Europe, and Croker has found a whole

school of

successors in Carleton, Griffin, Kennedy, Curtin, and Douglas Hyde.

Scotland had

the great name of Campbell, and has still efficient followers in

MacDougall, MacInnes,

Carmichael, Macleod, and Campbell of Tiree. Gallant little Wales has no

name to

rank alongside these; in this department the Cymru have shown less

vigour than the

Gaedhel. Perhaps the Eisteddfod, by offering prizes for the collection

of Welsh

folk-tales, may remove this inferiority. Meanwhile Wales must be

content to be somewhat

scantily represented among the Fairy Tales of the Celts, while the

extinct Cornish

tongue has only contributed one tale.