| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

The Lad with

the Goat-Skin

"Never

say't twice, mother," says Tom — "here goes." When he

had it gathered and tied, what should come up but a big giant, nine

foot high, and

made a lick of a club at him. Well become Tom, he jumped a-one side,

and picked

up a ram-pike; and the first crack he gave the big fellow, he made him

kiss the

clod. "If

you have e'er a prayer," says Tom, "now's the time to say it, before I

make fragments of you." "I

have no prayers," says the giant; "but if you spare my life I'll give

you that club; and as long as you keep from sin, you'll win every

battle you ever

fight with it." Tom made

no bones about letting him off; and as soon as he got the club in his

hands, he

sat down on the bresna, and gave it a tap with the kippeen, and says,

"Faggot,

I had great trouble gathering you, and run the risk of my life for you,

the least

you can do is to carry me home." And sure enough, the wind o' the word

was

all it wanted. It went off through the wood, groaning and crackling,

till it came

to the widow's door. Well,

when the sticks were all burned, Tom was sent off again to pick more;

and this time

he had to fight with a giant that had two heads on him. Tom had a

little more trouble

with him — that's all; and the prayers he said, was to give Tom a fife;

that nobody

could help dancing when he was playing it. Begonies, he made the big

faggot dance

home, with himself sitting on it. The next giant was a beautiful boy

with three

heads on him. He had neither prayers nor catechism no more nor the

others; and so

he gave Tom a bottle of green ointment, that wouldn't let you be

burned, nor scalded,

nor wounded. "And now," says he, "there's no more of us. You may

come and gather sticks here till little Lunacy Day in Harvest, without

giant or

fairy-man to disturb you." Well,

now, Tom was prouder nor ten paycocks, and used to take a walk down

street in the

heel of the evening; but some o' the little boys had no more manners

than if they

were Dublin jackeens, and put out their tongues at Tom's club and Tom's

goat-skin.

He didn't like that at all, and it would be mean to give one of them a

clout. At

last, what should come through the town but a kind of a bellman, only

it's a big

bugle he had, and a huntsman's cap on his head, and a kind of a painted

shirt. So

this — he wasn't a bellman, and I don't know what to call him —

bugleman, maybe,

proclaimed that the King of Dublin's daughter was so melancholy that

she didn't

give a laugh for seven years, and that her father would grant her in

marriage to

whoever could make her laugh three times. "That's

the very thing for me to try," says Tom; and so, without burning any

more daylight,

he kissed his mother, curled his club at the little boys, and off he

set along the

yalla highroad to the town of Dublin. At last

Tom came to one of the city gates, and the guards laughed and cursed at

him instead

of letting him in. Tom stood it all for a little time, but at last one

of them

— out of fun, as he said — drove his bayonet half an inch or so into

his side. Tom

done nothing but take the fellow by the scruff o' the neck and the

waistband of

his corduroys, and fling him into the canal. Some run to pull the

fellow out, and

others to let manners into the vulgarian with their swords and daggers;

but a tap

from his club sent them headlong into the moat or down on the stones,

and they were

soon begging him to stay his hands. So at

last one of them was glad enough to show Tom the way to the

palace-yard; and there

was the king, and the queen, and the princess, in a gallery, looking at

all sorts

of wrestling, and sword-playing, and long-dances, and mumming, all to

please the

princess; but not a smile came over her handsome face. Well,

they all stopped when they seen the young giant, with his boy's face,

and long black

hair, and his short curly beard — for his poor mother couldn't afford

to buy razors

— and his great strong arms, and bare legs, and no covering but the

goat-skin that

reached from his waist to his knees. But an envious wizened bit of a

fellow, with

a red head, that wished to be married to the princess, and didn't like

how she opened

her eyes at Tom, came forward, and asked his business very snappishly. "My

business," says Tom, says he, "is to make the beautiful princess, God

bless her, laugh three times." "Do

you see all them merry fellows and skilful swordsmen," says the other,

"that

could eat you up with a grain of salt, and not a mother's soul of 'em

ever got a

laugh from her these seven years?" So the

fellows gathered round Tom, and the bad man aggravated him till he told

them he

didn't care a pinch o' snuff for the whole bilin' of 'em; let 'em come

on, six at

a time, and try what they could do. The king,

who was too far off to hear what they were saying, asked what did the

stranger want. "He

wants," says the red-headed fellow, "to make hares of your best men." "Oh!"

says the king, "if that's the way, let one of 'em turn out and try his

mettle." So one

stood forward, with sword and pot-lid, and made a cut at Tom. He struck

the fellow's

elbow with the club, and up over their heads flew the sword, and down

went the owner

of it on the gravel from a thump he got on the helmet. Another took his

place, and

another, and another, and then half a dozen at once, and Tom sent

swords, helmets,

shields, and bodies, rolling over and over, and themselves bawling out

that they

were kilt, and disabled, and damaged, and rubbing their poor elbows and

hips, and

limping away. Tom contrived not to kill any one; and the princess was

so amused,

that she let a great sweet laugh out of her that was heard over all the

yard. "King

of Dublin," says Tom, "I've quarter your daughter." And the

king didn't know whether he was glad or sorry, and all the blood in the

princess's

heart run into her cheeks. So there

was no more fighting that day, and Tom was invited to dine with the

royal family.

Next day, Redhead told Tom of a wolf, the size of a yearling heifer,

that used to

be serenading about the walls, and eating people and cattle; and said

what a pleasure

it would give the king to have it killed. "With

all my heart," says Tom; "send a jackeen to show me where he lives, and

we'll see how he behaves to a stranger." The princess

was not well pleased, for Tom looked a different person with fine

clothes and a

nice green birredh over his long curly hair; and besides, he'd got one

laugh out

of her. However, the king gave his consent; and in an hour and a half

the horrible

wolf was walking into the palace-yard, and Tom a step or two behind,

with his club

on his shoulder, just as a shepherd would be walking after a pet lamb. The king

and queen and princess were safe up in their gallery, but the officers

and people

of the court that wor padrowling about the great bawn, when they saw

the big baste

coming in, gave themselves up, and began to make for doors and gates;

and the wolf

licked his chops, as if he was saying, "Wouldn't I enjoy a breakfast

off a

couple of yez!" The king

shouted out, "O Tom with the Goat-skin, take away that terrible wolf,

and you

must have all my daughter." But Tom

didn't mind him a bit. He pulled out his flute and began to play like

vengeance;

and dickens a man or boy in the yard but began shovelling away heel and

toe, and

the wolf himself was obliged to get on his hind legs and dance "Tatther

Jack

Walsh," along with the rest. A good deal of the people got inside, and

shut

the doors, the way the hairy fellow wouldn't pin them; but Tom kept

playing, and

the outsiders kept dancing and shouting, and the wolf kept dancing and

roaring with

the pain his legs were giving him; and all the time he had his eyes on

Redhead,

who was shut out along with the rest. Wherever Redhead went, the wolf

followed,

and kept one eye on him and the other on Tom, to see if he would give

him leave

to eat him. But Tom shook his head, and never stopped the tune, and

Redhead never

stopped dancing and bawling, and the wolf dancing and roaring, one leg

up and the

other down, and he ready to drop out of his standing from fair

tiresomeness.  When the princess seen that there was no fear of any one being kilt, she was so divarted by the stew that Redhead was in, that she gave another great laugh; and well become Tom, out he cried, "King of Dublin, I have two halves of your daughter." "Oh, halves or alls," says the king, "put away that divel of a wolf, and we'll see about it." So Tom

put his flute in his pocket, and says he to the baste that was sittin'

on his currabingo

ready to faint, "Walk off to your mountain, my fine fellow, and live

like a

respectable baste; and if ever I find you come within seven miles of

any town, I'll

— " He said

no more, but spit in his fist, and gave a flourish of his club. It was

all the poor

divel of a wolf wanted: he put his tail between his legs, and took to

his pumps

without looking at man or mortal, and neither sun, moon, or stars ever

saw him in

sight of Dublin again. At dinner

every one laughed but the foxy fellow; and sure enough he was laying

out how he'd

settle poor Tom next day.

"So,"

says Tom to the king, "will you let me have the other half of the

princess

if I bring you the flail?" "No,

no," says the princess; "I'd rather never be your wife than see you in

that danger." But Redhead

whispered and nudged Tom about how shabby it would look to reneague the

adventure.

So he asked which way he was to go, and Redhead directed him. Well,

he travelled and travelled, till he came in sight of the walls of hell;

and, bedad,

before he knocked at the gates, he rubbed himself over with the

greenish ointment.

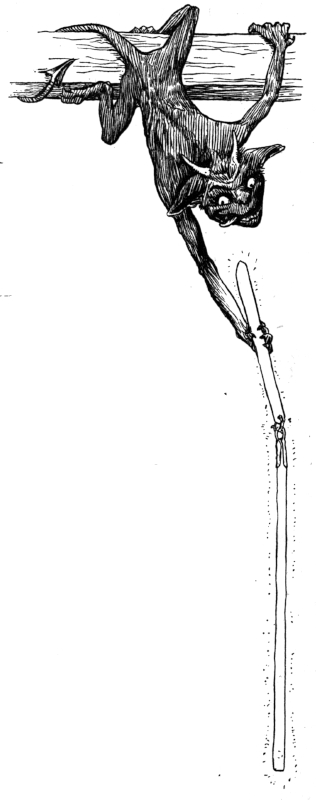

When he knocked, a hundred little imps popped their heads out through

the bars,

and axed him what he wanted. "I

want to speak to the big divel of all," says Tom: "open the gate." It wasn't

long till the gate was thrune open, and the Ould Boy received Tom with

bows and

scrapes, and axed his business. "My

business isn't much," says Tom. "I only came for the loan of that flail

that I see hanging on the collar-beam, for the king of Dublin to give a

thrashing

to the Danes." "Well,"

says the other, "the Danes is much better customers to me; but since

you walked

so far I won't refuse. Hand that flail," says he to a young imp; and he

winked

the far-off eye at the same time. So, while some were barring the

gates, the young

devil climbed up, and took down the flail that had the handstaff and

booltheen both

made out of red-hot iron. The little vagabond was grinning to think how

it would

burn the hands o' Tom, but the dickens a burn it made on him, no more

nor if it

was a good oak sapling. "Thankee,"

says Tom. "Now would you open the gate for a body, and I'll give you no

more

trouble." "Oh,

tramp!" says Ould Nick; "is that the way? It is easier getting inside

them gates than getting out again. Take that tool from him, and give

him a dose

of the oil of stirrup." So one

fellow put out his claws to seize on the flail, but Tom gave him such a

welt of

it on the side of the head that he broke off one of his horns, and made

him roar

like a devil as he was. Well, they rushed at Tom, but he gave them,

little and big,

such a thrashing as they didn't forget for a while. At last says the

ould thief

of all, rubbing his elbow, "Let the fool out; and woe to whoever lets

him in

again, great or small." So out

marched Tom, and away with him, without minding the shouting and

cursing they kept

up at him from the tops of the walls; and when he got home to the big

bawn of the

palace, there never was such running and racing as to see himself and

the flail.

When he had his story told, he laid down the flail on the stone steps,

and bid no

one for their lives to touch it. If the king, and queen, and princess,

made much

of him before, they made ten times more of him now; but Redhead, the

mean scruff-hound,

stole over, and thought to catch hold of the flail to make an end of

him. His fingers

hardly touched it, when he let a roar out of him as if heaven and earth

were coming

together, and kept flinging his arms about and dancing, that it was

pitiful to look

at him. Tom run at him as soon as he could rise, caught his hands in

his own two,

and rubbed them this way and that, and the burning pain left them

before you could

reckon one. Well the poor fellow, between the pain that was only just

gone, and

the comfort he was in, had the comicalest face that you ever see, it

was such a

mixtherum-gatherum of laughing and crying. Everybody burst out a

laughing — the

princess could not stop no more than the rest; and then says Tom, "Now,

ma'am,

if there were fifty halves of you, I hope you'll give me them all." Well,

the princess looked at her father, and by my word, she came over to

Tom, and put

her two delicate hands into his two rough ones, and I wish it was

myself was in

his shoes that day! Tom would

not bring the flail into the palace. You may be sure no other body went

near it;

and when the early risers were passing next morning, they found two

long clefts

in the stone, where it was after burning itself an opening downwards,

nobody could

tell how far. But a messenger came in at noon, and said that the Danes

were so frightened

when they heard of the flail coming into Dublin, that they got into

their ships,

and sailed away. Well,

I suppose, before they were married, Tom got some man, like Pat Mara of

Tomenine,

to learn him the "principles of politeness," fluxions, gunnery, and

fortification,

decimal fractions, practice, and the rule of three direct, the way he'd

be able

to keep up a conversation with the royal family. Whether he ever lost

his time learning

them sciences, I'm not sure, but it's as sure as fate that his mother

never more

saw any want till the end of her days.  |

ong ago, a poor widow woman

lived down

near the iron forge, by Enniscorth, and she was so poor she had no

clothes to put

on her son; so she used to fix him in the ash-hole, near the fire, and

pile the

warm ashes about him; and according as he grew up, she sunk the pit

deeper. At last,

by hook or by crook, she got a goat-skin, and fastened it round his

waist, and he

felt quite grand, and took a walk down the street. So says she to him

next morning,

"Tom, you thief, you never done any good yet, and you six foot high,

and past

nineteen; — take that rope and bring me a faggot from the wood."

ong ago, a poor widow woman

lived down

near the iron forge, by Enniscorth, and she was so poor she had no

clothes to put

on her son; so she used to fix him in the ash-hole, near the fire, and

pile the

warm ashes about him; and according as he grew up, she sunk the pit

deeper. At last,

by hook or by crook, she got a goat-skin, and fastened it round his

waist, and he

felt quite grand, and took a walk down the street. So says she to him

next morning,

"Tom, you thief, you never done any good yet, and you six foot high,

and past

nineteen; — take that rope and bring me a faggot from the wood." "Well,

to be sure!" says he, "King of Dublin, you are in luck. There's the

Danes

moidhering us to no end. Deuce run to Lusk wid 'em! and if any one can

save us from

'em, it is this gentleman with the goat-skin. There is a flail hangin'

on the collar-beam,

in hell, and neither Dane nor devil can stand before it."

"Well,

to be sure!" says he, "King of Dublin, you are in luck. There's the

Danes

moidhering us to no end. Deuce run to Lusk wid 'em! and if any one can

save us from

'em, it is this gentleman with the goat-skin. There is a flail hangin'

on the collar-beam,

in hell, and neither Dane nor devil can stand before it."