| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

Hudden and Dudden and Donald O'Neary

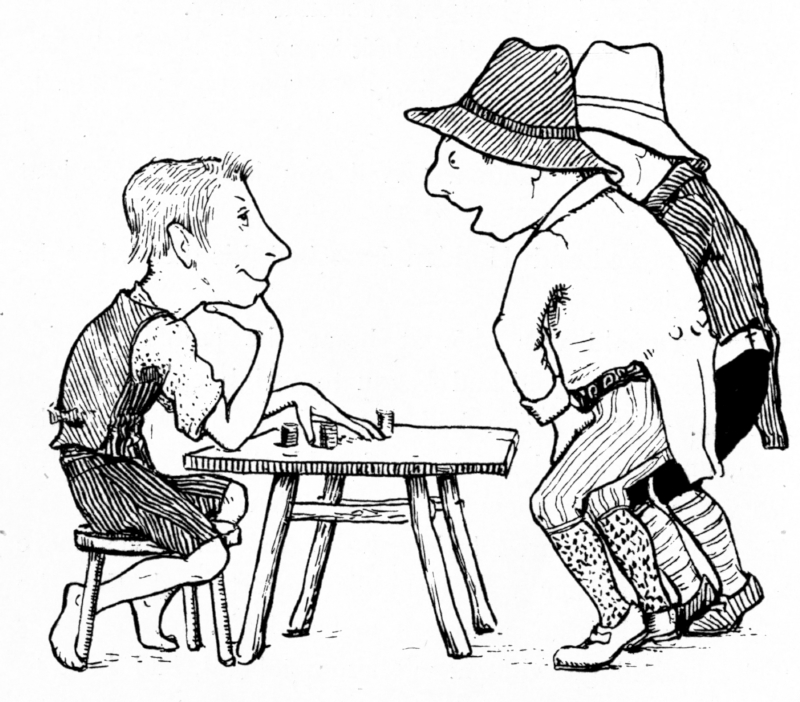

One day

Hudden met Dudden, and they were soon grumbling as usual, and all to

the tune of

"If only we could get that vagabond Donald O'Neary out of the country." "Let's

kill Daisy," said Hudden at last; "if that doesn't make him clear out,

nothing will." No sooner

said than agreed, and it wasn't dark before Hudden and Dudden crept up

to the little

shed where lay poor Daisy trying her best to chew the cud, though she

hadn't had

as much grass in the day as would cover your hand. And when Donald came

to see if

Daisy was all snug for the night, the poor beast had only time to lick

his hand

once before she died. Well,

Donald was a shrewd fellow, and downhearted though he was, began to

think if he

could get any good out of Daisy's death. He thought and he thought, and

the next

day you could have seen him trudging off early to the fair, Daisy's

hide over his

shoulder, every penny he had jingling in his pockets. Just before he

got to the

fair, he made several slits in the hide, put a penny in each slit,

walked into the

best inn of the town as bold as if it belonged to him, and, hanging the

hide up

to a nail in the wall, sat down. "Some

of your best whisky," says he to the landlord. But the

landlord didn't like his looks. "Is it fearing I won't pay you, you

are?"

says Donald; "why I have a hide here that gives me all the money I

want."

And with that he hit it a whack with his stick and out hopped a penny.

The landlord

opened his eyes, as you may fancy. "What'll

you take for that hide?" "It's

not for sale, my good man." "Will

you take a gold piece?" "It's

not for sale, I tell you. Hasn't it kept me and mine for years?" and

with that

Donald hit the hide another whack and out jumped a second penny. Well,

the long and the short of it was that Donald let the hide go, and, that

very evening,

who but he should walk up to Hudden's door? "Good-evening,

Hudden. Will you lend me your best pair of scales?" Hudden

stared and Hudden scratched his head, but he lent the scales. When Donald

was safe at home, he pulled out his pocketful of bright gold and began

to weigh

each piece in the scales. But Hudden had put a lump of butter at the

bottom, and

so the last piece of gold stuck fast to the scales when he took them

back to Hudden. If Hudden

had stared before, he stared ten times more now, and no sooner was

Donald's back

turned, than he was of as hard as he could pelt to Dudden's. "Good-evening,

Dudden.

That

vagabond, bad

luck to himó" "You

mean Donald O'Neary?" "And

who else should I mean? He's back here weighing out sackfuls of gold." "How

do you know that?" "Here

are my scales that he borrowed, and here's a gold piece still sticking

to them." Off they

went together, and they came to Donald's door. Donald had finished

making the last

pile of ten gold pieces. And he couldn't finish because a piece had

stuck to the

scales. In they

walked without an "If you please" or "By your leave." "Well,

I never!" that was all they could say.  "Good-evening,

Hudden; good-evening, Dudden. Ah! you thought you had played me a fine

trick, but

you never did me a better turn in all your lives. When I found poor

Daisy dead,

I thought to myself, 'Well, her hide may fetch something;' and it did.

Hides are

worth their weight in gold in the market just now." Hudden

nudged Dudden, and Dudden winked at Hudden. "Good-evening,

Donald O'Neary." "Good-evening,

kind friends." The next

day there wasn't a cow or a calf that belonged to Hudden or Dudden but

her hide

was going to the fair in Hudden's biggest cart drawn by Dudden's

strongest pair

of horses. When they

came to the fair, each one took a hide over his arm, and there they

were walking

through the fair, bawling out at the top of their voices: "Hides to

sell! hides

to sell!" Out came

the tanner: "How

much for your hides, my good men?" "Their

weight in gold." "It's

early in the day to come out of the tavern." That was

all the tanner said, and back he went to his yard. "Hides

to sell! Fine fresh hides to sell!" Out came

the cobbler. "How

much for your hides, my men?" "Their

weight in gold." "Is

it making game of me you are! Take that for your pains," and the

cobbler dealt

Hudden a blow that made him stagger. Up the

people came running from one end of the fair to the other. "Here

are a couple of vagabonds selling hides at their weight in gold," said

the

cobbler. "Hold

'em fast; hold 'em fast!" bawled the innkeeper, who was the last to

come up,

he was so fat. "I'll wager it's one of the rogues who tricked me out of

thirty

gold pieces yesterday for a wretched hide." It was

more kicks than halfpence that Hudden and Dudden got before they were

well on their

way home again, and they didn't run the slower because all the dogs of

the town

were at their heels. Well,

as you may fancy, if they loved Donald little before, they loved him

less now. "What's

the matter, friends?" said he, as he saw them tearing along, their hats

knocked

in, and their coats torn off, and their faces black and blue. "Is it

fighting

you've been? or mayhap you met the police, ill luck to them?" "We'll

police you, you vagabond. It's mighty smart you thought yourself,

deluding us with

your lying tales." "Who

deluded you? Didn't you see the gold with your own two eyes?" But it

was no use talking. Pay for it he must, and should. There was a

meal-sack handy,

and into it Hudden and Dudden popped Donald O'Neary, tied him up tight,

ran a pole

through the knot, and off they started for the Brown Lake of the Bog,

each with

a pole-end on his shoulder, and Donald O'Neary between. But the

Brown Lake was far, the road was dusty, Hudden and Dudden were sore and

weary, and

parched with thirst. There was an inn by the roadside. "Let's

go in," said Hudden; "I'm dead beat. It's heavy he is for the little he

had to eat." If Hudden

was willing, so was Dudden. As for Donald, you may be sure his leave

wasn't asked,

but he was lumped down at the inn door for all the world as if he had

been a sack

of potatoes. "Sit

still, you vagabond," said Dudden; "if we don't mind waiting, you

needn't." Donald

held his peace, but after a while he heard the glasses clink, and

Hudden singing

away at the top of his voice. "I

won't have her, I tell you; I won't have her!" said Donald. But nobody

heeded

what he said. "I

won't have her, I tell you; I won't have her!" said Donald, and this

time he

said it louder; but nobody heeded what he said. "I

won't have her, I tell you; I won't have her!" said Donald; and this

time he

said it as loud as he could. "And

who won't you have, may I be so bold as to ask?" said a farmer, who had

just

come up with a drove of cattle, and was turning in for a glass. "It's

the king's daughter. They are bothering the life out of me to marry

her." "You're

the lucky fellow. I'd give something to be in your shoes." "Do

you see that now! Wouldn't it be a fine thing for a farmer to be

marrying a princess,

all dressed in gold and jewels?" "Jewels,

do you say? Ah, now, couldn't you take me with you?" "Well,

you're an honest fellow, and as I don't care for the king's daughter,

though she's

as beautiful as the day, and is covered with jewels from top to toe,

you shall have

her. Just undo the cord, and let me out; they tied me up tight, as they

knew I'd

run away from her." Out crawled

Donald; in crept the farmer. "Now

lie still, and don't mind the shaking; it's only rumbling over the

palace steps

you'll be. And maybe they'll abuse you for a vagabond, who won't have

the king's

daughter; but you needn't mind that. Ah! it's a deal I'm giving up for

you, sure

as it is that I don't care for the princess." "Take

my cattle in exchange," said the farmer; and you may guess it wasn't

long before

Donald was at their tails driving them homewards. Out came

Hudden and Dudden, and the one took one end of the pole, and the other

the other. "I'm

thinking he's heavier," said Hudden. "Ah,

never mind," said Dudden; "it's only a step now to the Brown Lake." "I'll

have her now! I'll have her now!" bawled the farmer, from inside the

sack. "By

my faith, and you shall though," said Hudden, and he laid his stick

across

the sack. "I'll

have her! I'll have her!" bawled the farmer, louder than ever. "Well,

here you are," said Dudden, for they were now come to the Brown Lake,

and,

unslinging the sack, they pitched it plump into the lake. "You'll

not be playing your tricks on us any longer," said Hudden. "True

for you," said Dudden. "Ah, Donald, my boy, it was an ill day when you

borrowed my scales." Off they

went, with a light step and an easy heart, but when they were near

home, who should

they see but Donald O'Neary, and all around him the cows were grazing,

and the calves

were kicking up their heels and butting their heads together. "Is

it you, Donald?" said Dudden. "Faith, you've been quicker than we have." "True

for you, Dudden, and let me thank you kindly; the turn was good, if the

will was

ill. You'll have heard, like me, that the Brown Lake leads to the Land

of Promise.

I always put it down as lies, but it is just as true as my word. Look

at the cattle." Hudden

stared, and Dudden gaped; but they couldn't get over the cattle; fine

fat cattle

they were too. "It's

only the worst I could bring up with me," said Donald O'Neary; "the

others

were so fat, there was no driving them. Faith, too, it's little wonder

they didn't

care to leave, with grass as far as you could see, and as sweet and

juicy as fresh

butter." "Ah,

now, Donald, we haven't always been friends," said Dudden, "but, as I

was just saying, you were ever a decent lad, and you'll show us the

way, won't you?" "I

don't see that I'm called upon to do that; there is a power more cattle

down there.

Why shouldn't I have them all to myself?" "Faith,

they may well say, the richer you get, the harder the heart. You always

were a neighbourly

lad, Donald. You wouldn't wish to keep the luck all to yourself?" "True

for you, Hudden, though 'tis a bad example you set me. But I'll not be

thinking

of old times. There is plenty for all there, so come along with me." Off they

trudged, with a light heart and an eager step. When they came to the

Brown Lake,

the sky was full of little white clouds, and, if the sky was full, the

lake was

as full. "Ah!

now, look, there they are," cried Donald, as he pointed to the clouds

in the

lake. "Where?

where?" cried Hudden, and "Don't be greedy!" cried Dudden, as he

jumped his hardest to be up first with the fat cattle. But if he jumped

first, Hudden

wasn't long behind. |

here was once upon a time

two farmers,

and their names were Hudden and Dudden. They had poultry in their

yards, sheep on

the uplands, and scores of cattle in the meadow-land alongside the

river. But for

all that they weren't happy. For just between their two farms there

lived a poor

man by the name of Donald O'Neary. He had a hovel over his head and a

strip of grass

that was barely enough to keep his one cow, Daisy, from starving, and,

though she

did her best, it was but seldom that Donald got a drink of milk or a

roll of butter

from Daisy. You would think there was little here to make Hudden and

Dudden jealous,

but so it is, the more one has the more one wants, and Donald's

neighbours lay awake

of nights scheming how they might get hold of his little strip of

grass-land. Daisy,

poor thing, they never thought of; she was just a bag of bones.

here was once upon a time

two farmers,

and their names were Hudden and Dudden. They had poultry in their

yards, sheep on

the uplands, and scores of cattle in the meadow-land alongside the

river. But for

all that they weren't happy. For just between their two farms there

lived a poor

man by the name of Donald O'Neary. He had a hovel over his head and a

strip of grass

that was barely enough to keep his one cow, Daisy, from starving, and,

though she

did her best, it was but seldom that Donald got a drink of milk or a

roll of butter

from Daisy. You would think there was little here to make Hudden and

Dudden jealous,

but so it is, the more one has the more one wants, and Donald's

neighbours lay awake

of nights scheming how they might get hold of his little strip of

grass-land. Daisy,

poor thing, they never thought of; she was just a bag of bones.