| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOM

|

| Guleesh

Hardly

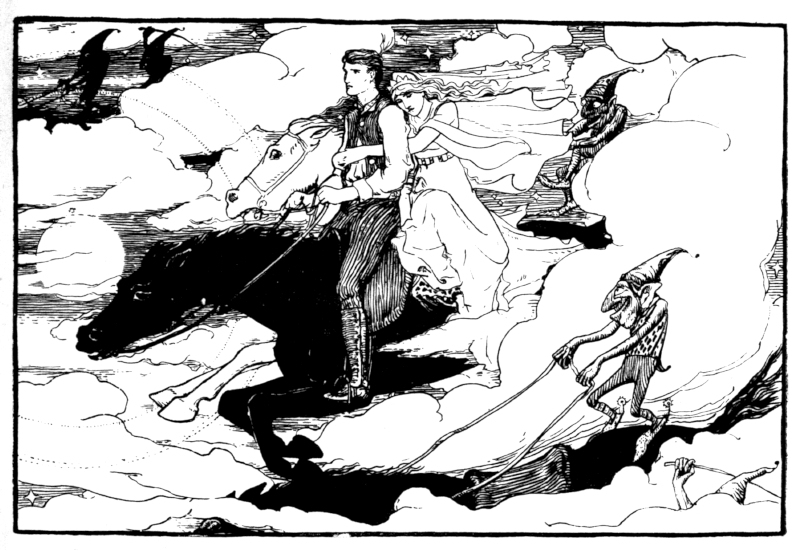

was the word out of his mouth when he heard a great noise coming like

the sound

of many people running together, and talking, and laughing, and making

sport, and

the sound went by him like a whirl of wind, and he was listening to it

going into

the rath. "Musha, by my soul," says he, "but ye're merry enough,

and I'll follow ye." What was

in it but the fairy host, though he did not know at first that it was

they who were

in it, but he followed them into the rath. It's there he heard the fulparnee,

and the folpornee, the rap-lay-hoota, and the roolya-boolya,

that they had there, and every man of them crying out as loud as he

could: "My

horse, and bridle, and saddle! My horse, and bridle, and saddle!" "By

my hand," said Guleesh, "my boy, that's not bad. I'll imitate ye,"

and he cried out as well as they: "My horse, and bridle, and saddle! My

horse,

and bridle, and saddle!" And on the moment there was a fine horse with

a bridle

of gold, and a saddle of silver, standing before him. He leaped up on

it, and the

moment he was on its back he saw clearly that the rath was full of

horses, and of

little people going riding on them. Said a

man of them to him: "Are you coming with us to-night, Guleesh?" "I

am surely," said Guleesh. "If

you are, come along," said the little man, and out they went all

together,

riding like the wind, faster than the fastest horse ever you saw

a-hunting, and

faster than the fox and the hounds at his tail. The cold

winter's wind that was before them, they overtook her, and the cold

winter's wind

that was behind them, she did not overtake them. And stop nor stay of

that full

race, did they make none, until they came to the brink of the sea. Then every

one of them said: "Hie over cap! Hie over cap!" and that moment they

were

up in the air, and before Guleesh had time to remember where he was,

they were down

on dry land again, and were going like the wind. At last

they stood still, and a man of them said to Guleesh: "Guleesh, do you

know

where you are now?" "Not

a know," says Guleesh. "You're

in France, Guleesh," said he. "The daughter of the king of France is to

be married to-night, the handsomest woman that the sun ever saw, and we

must do

our best to bring her with us; if we're only able to carry her off; and

you must

come with us that we may be able to put the young girl up behind you on

the horse,

when we'll be bringing her away, for it's not lawful for us to put her

sitting behind

ourselves. But you're flesh and blood, and she can take a good grip of

you, so that

she won't fall off the horse. Are you satisfied, Guleesh, and will you

do what we're

telling you?" "Why

shouldn't I be satisfied?" said Guleesh. "I'm satisfied, surely, and

anything

that ye will tell me to do I'll do it without doubt." They got

off their horses there, and a man of them said a word that Guleesh did

not understand,

and on the moment they were lifted up, and Guleesh found himself and

his companions

in the palace. There was a great feast going on there, and there was

not a nobleman

or a gentleman in the kingdom but was gathered there, dressed in silk

and satin,

and gold and silver, and the night was as bright as the day with all

the lamps and

candles that were lit, and Guleesh had to shut his two eyes at the

brightness. When

he opened them again and looked from him, he thought he never saw

anything as fine

as all he saw there. There were a hundred tables spread out, and their

full of meat

and drink on each table of them, flesh-meat, and cakes and sweetmeats,

and wine

and ale, and every drink that ever a man saw. The musicians were at the

two ends

of the hall, and they were playing the sweetest music that ever a man's

ear heard,

and there were young women and fine youths in the middle of the hall,

dancing and

turning, and going round so quickly and so lightly, that it put a soorawn

in Guleesh's head to be looking at them. There were more there playing

tricks, and

more making fun and laughing, for such a feast as there was that day

had not been

in France for twenty years, because the old king had no children alive

but only

the one daughter, and she was to be married to the son of another king

that night.

Three days the feast was going on, and the third night she was to be

married, and

that was the night that Guleesh and the sheehogues came, hoping, if

they could,

to carry off with them the king's young daughter. Guleesh

and his companions were standing together at the head of the hall,

where there was

a fine altar dressed up, and two bishops behind it waiting to marry the

girl, as

soon as the right time should come. Now nobody could see the

sheehogues, for they

said a word as they came in, that made them all invisible, as if they

had not been

in it at all. "Tell

me which of them is the king's daughter," said Guleesh, when he was

becoming

a little used to the noise and the light. "Don't

you see her there away from you?" said the little man that he was

talking to. Guleesh

looked where the little man was pointing with his finger, and there he

saw the loveliest

woman that was, he thought, upon the ridge of the world. The rose and

the lily were

fighting together in her face, and one could not tell which of them got

the victory.

Her arms and hands were like the lime, her mouth as red as a strawberry

when it

is ripe, her foot was as small and as light as another one's hand, her

form was

smooth and slender, and her hair was falling down from her head in

buckles of gold.

Her garments and dress were woven with gold and silver, and the bright

stone that

was in the ring on her hand was as shining as the sun. Guleesh

was nearly blinded with all the loveliness and beauty that was in her;

but when

he looked again, he saw that she was crying, and that there was the

trace of tears

in her eyes. "It can't be," said Guleesh, "that there's grief on

her, when everybody round her is so full of sport and merriment." "Musha,

then, she is grieved," said the little man; "for it's against her own

will she's marrying, and she has no love for the husband she is to

marry. The king

was going to give her to him three years ago, when she was only

fifteen, but she

said she was too young, and requested him to leave her as she was yet.

The king

gave her a year's grace, and when that year was up he gave her another

year's grace,

and then another; but a week or a day he would not give her longer, and

she is eighteen

years old to-night, and it's time for her to marry; but, indeed," says

he,

and he crooked his mouth in an ugly way — "indeed, it's no king's son

she'll

marry, if I can help it." Guleesh

pitied the handsome young lady greatly when he heard that, and he was

heart-broken

to think that it would be necessary for her to marry a man she did not

like, or,

what was worse, to take a nasty sheehogue for a husband. However, he

did not say

a word, though he could not help giving many a curse to the ill-luck

that was laid

out for himself, to be helping the people that were to snatch her away

from her

home and from her father. He began

thinking, then, what it was he ought to do to save her, but he could

think of nothing.

"Oh! if I could only give her some help and relief," said he, "I

wouldn't care whether I were alive or dead; but I see nothing that I

can do for

her." He was

looking on when the king's son came up to her and asked her for a kiss,

but she

turned her head away from him. Guleesh had double pity for her then,

when he saw

the lad taking her by the soft white hand, and drawing her out to

dance. They went

round in the dance near where Guleesh was, and he could plainly see

that there were

tears in her eyes. When the

dancing was over, the old king, her father, and her mother the queen,

came up and

said that this was the right time to marry her, that the bishop was

ready, and it

was time to put the wedding-ring on her and give her to her husband. The king took the youth by the hand, and the queen took her daughter, and they went up together to the altar, with the lords and great people following them.

When they

came near the altar, and were no more than about four yards from it,

the little

sheehogue stretched out his foot before the girl, and she fell. Before

she was able

to rise again he threw something that was in his hand upon her, said a

couple of

words, and upon the moment the maiden was gone from amongst them.

Nobody could see

her, for that word made her invisible. The little maneen seized

her and raised

her up behind Guleesh, and the king nor no one else saw them, but out

with them

through the hall till they came to the door. Oro! dear

Mary! it's there the pity was, and the trouble, and the crying, and the

wonder,

and the searching, and the rookawn, when that lady disappeared

from their

eyes, and without their seeing what did it. Out of the door of the

palace they went,

without being stopped or hindered, for nobody saw them, and, "My horse,

my

bridle, and saddle!" says every man of them. "My horse, my bridle, and

saddle!" says Guleesh; and on the moment the horse was standing ready

caparisoned

before him. "Now, jump up, Guleesh," said the little man, "and put

the lady behind you, and we will be going; the morning is not far off

from us now." Guleesh

raised her up on the horse's back, and leaped up himself before her,

and, "Rise,

horse," said he; and his horse, and the other horses with him, went in

a full

race until they came to the sea. "Hie

over cap!" said every man of them. "Hie

over cap!" said Guleesh; and on the moment the horse rose under him,

and cut

a leap in the clouds, and came down in Erin. They did

not stop there, but went of a race to the place where was Guleesh's

house and the

rath. And when they came as far as that, Guleesh turned and caught the

young girl

in his two arms, and leaped off the horse. "I

call and cross you to myself, in the name of God!" said he; and on the

spot,

before the word was out of his mouth, the horse fell down, and what was

in it but

the beam of a plough, of which they had made a horse; and every other

horse they

had, it was that way they made it. Some of them were riding on an old

besom, and

some on a broken stick, and more on a bohalawn or a hemlock-stalk. The good

people called out together when they heard what Guleesh said: "Oh!

Guleesh, you clown, you thief, that no good may happen you, why did you

play that

trick on us?" But they

had no power at all to carry off the girl, after Guleesh had

consecrated her to

himself. "Oh!

Guleesh, isn't that a nice turn you did us, and we so kind to you? What

good have

we now out of our journey to France. Never mind yet, you clown, but

you'll pay us

another time for this. Believe us, you'll repent it." "He'll

have no good to get out of the young girl," said the little man that

was talking

to him in the palace before that, and as he said the word he moved over

to her and

struck her a slap on the side of the head. "Now," says he, "she'll

be without talk any more; now, Guleesh, what good will she be to you

when she'll

be dumb? It's time for us to go — but you'll remember us, Guleesh!" When he

said that he stretched out his two hands, and before Guleesh was able

to give an

answer, he and the rest of them were gone into the rath out of his

sight, and he

saw them no more. He turned

to the young woman and said to her: "Thanks be to God, they're gone.

Would

you not sooner stay with me than with them?" She gave him no answer.

"There's

trouble and grief on her yet," said Guleesh in his own mind, and he

spoke to

her again: "I am afraid that you must spend this night in my father's

house,

lady, and if there is anything that I can do for you, tell me, and I'll

be your

servant." The

beautiful

girl remained silent, but there were tears in her eyes, and her face

was white and

red after each other. "Lady,"

said Guleesh, "tell me what you would like me to do now. I never

belonged at

all to that lot of sheehogues who carried you away with them. I am the

son of an

honest farmer, and I went with them without knowing it. If I'll be able

to send

you back to your father I'll do it, and I pray you make any use of me

now that you

may wish." He looked

into her face, and he saw the mouth moving as if she was going to

speak, but there

came no word from it. "It

cannot be," said Guleesh, "that you are dumb. Did I not hear you

speaking

to the king's son in the palace to-night? Or has that devil made you

really dumb,

when he struck his nasty hand on your jaw?" The girl

raised her white smooth hand, and laid her finger on her tongue, to

show him that

she had lost her voice and power of speech, and the tears ran out of

her two eyes

like streams, and Guleesh's own eyes were not dry, for as rough as he

was on the

outside he had a soft heart, and could not stand the sight of the young

girl, and

she in that unhappy plight. He began

thinking with himself what he ought to do, and he did not like to bring

her home

with himself to his father's house, for he knew well that they would

not believe

him, that he had been in France and brought back with him the king of

France's daughter,

and he was afraid they might make a mock of the young lady or insult

her. As he

was doubting what he ought to do, and hesitating, he chanced to

remember the priest.

"Glory be to God," said he, "I know now what I'll do; I'll bring

her to the priest's house, and he won't refuse me to keep the lady and

care for

her." He turned to the lady again and told her that he was loth to take

her

to his father's house, but that there was an excellent priest very

friendly to himself,

who would take good care of her, if she wished to remain in his house;

but that

if there was any other place she would rather go, he said he would

bring her to

it. She bent

her head, to show him she was obliged, and gave him to understand that

she was ready

to follow him any place he was going. "We will go to the priest's

house, then,"

said he; "he is under an obligation to me, and will do anything I ask

him." They went

together accordingly to the priest's house, and the sun was just rising

when they

came to the door. Guleesh beat it hard, and as early as it was the

priest was up,

and opened the door himself. He wondered when he saw Guleesh and the

girl, for he

was certain that it was coming wanting to be married they were. "Guleesh,

Guleesh, isn't it the nice boy you are that you can't wait till ten

o'clock or till

twelve, but that you must be coming to me at this hour, looking for

marriage, you

and your sweetheart? You ought to know that I can't marry you at such a

time, or,

at all events, can't marry you lawfully. But ubbubboo!" said he,

suddenly,

as he looked again at the young girl, "in the name of God, who have you

here?

Who is she, or how did you get her?" "Father,"

said Guleesh, "you can marry me, or anybody else, if you wish; but it's

not

looking for marriage I came to you now, but to ask you, if you please,

to give a

lodging in your house to this young lady." The priest

looked at him as though he had ten heads on him; but without putting

any other question

to him, he desired him to come in, himself and the maiden, and when

they came in,

he shut the door, brought them into the parlour, and put them sitting. "Now,

Guleesh," said he, "tell me truly who is this young lady, and whether

you're out of your senses really, or are only making a joke of me." "I'm

not telling a word of lie, nor making a joke of you," said Guleesh;

"but

it was from the palace of the king of France I carried off this lady,

and she is

the daughter of the king of France." He began

his story then, and told the whole to the priest, and the priest was so

much surprised

that he could not help calling out at times, or clapping his hands

together. When Guleesh

said from what he saw he thought the girl was not satisfied with the

marriage that

was going to take place in the palace before he and the sheehogues

broke it up,

there came a red blush into the girl's cheek, and he was more certain

than ever

that she had sooner be as she was — badly as she was — than be the

married wife

of the man she hated. When Guleesh said that he would be very thankful

to the priest

if he would keep her in his own house, the kind man said he would do

that as long

as Guleesh pleased, but that he did not know what they ought to do with

her, because

they had no means of sending her back to her father again. Guleesh

answered that he was uneasy about the same thing, and that he saw

nothing to do

but to keep quiet until they should find some opportunity of doing

something better.

They made it up then between themselves that the priest should let on

that it was

his brother's daughter he had, who was come on a visit to him from

another county,

and that he should tell everybody that she was dumb, and do his best to

keep every

one away from her. They told the young girl what it was they intended

to do, and

she showed by her eyes that she was obliged to them. Guleesh

went home then, and when his people asked him where he had been, he

said that he

had been asleep at the foot of the ditch, and had passed the night

there. There

was great wonderment on the priest's neighbours at the girl who came so

suddenly

to his house without any one knowing where she was from, or what

business she had

there. Some of the people said that everything was not as it ought to

be, and others,

that Guleesh was not like the same man that was in it before, and that

it was a

great story, how he was drawing every day to the priest's house, and

that the priest

had a wish and a respect for him, a thing they could not clear up at

all. That was

true for them, indeed, for it was seldom the day went by but Guleesh

would go to

the priest's house, and have a talk with him, and as often as he would

come he used

to hope to find the young lady well again, and with leave to speak;

but, alas! she

remained dumb and silent, without relief or cure. Since she had no

other means of

talking, she carried on a sort of conversation between herself and

himself, by moving

her hand and fingers, winking her eyes, opening and shutting her mouth,

laughing

or smiling, and a thousand other signs, so that it was not long until

they understood

each other very well. Guleesh was always thinking how he should send

her back to

her father; but there was no one to go with her, and he himself did not

know what

road to go, for he had never been out of his own country before the

night he brought

her away with him. Nor had the priest any better knowledge than he; but

when Guleesh

asked him, he wrote three or four letters to the king of France, and

gave them to

buyers and sellers of wares, who used to be going from place to place

across the

sea; but they all went astray, and never a one came to the king's hand. This was

the way they were for many months, and Guleesh was falling deeper and

deeper in

love with her every day, and it was plain to himself and the priest

that she liked

him. The boy feared greatly at last, lest the king should really hear

where his

daughter was, and take her back from himself, and he besought the

priest to write

no more, but to leave the matter to God. So they

passed the time for a year, until there came a day when Guleesh was

lying by himself,

on the grass, on the last day of the last month in autumn, and he was

thinking over

again in his own mind of everything that happened to him from the day

that he went

with the sheehogues across the sea. He remembered then, suddenly, that

it was one

November night that he was standing at the gable of the house, when the

whirlwind

came, and the sheehogues in it, and he said to himself: "We have

November night

again to-day, and I'll stand in the same place I was last year, until I

see if the

good people come again. Perhaps I might see or hear something that

would be useful

to me, and might bring back her talk again to Mary" — that was the name

himself

and the priest called the king's daughter, for neither of them knew her

right name.

He told his intention to the priest, and the priest gave him his

blessing. Guleesh

accordingly went to the old rath when the night was darkening, and he

stood with

his bent elbow leaning on a grey old flag, waiting till the middle of

the night

should come. The moon rose slowly; and it was like a knob of fire

behind him; and

there was a white fog which was raised up over the fields of grass and

all damp

places, through the coolness of the night after a great heat in the

day. The night

was calm as is a lake when there is not a breath of wind to move a wave

on it, and

there was no sound to be heard but the cronawn of the insects

that would

go by from time to time, or the hoarse sudden scream of the wild-geese,

as they

passed from lake to lake, half a mile up in the air over his head; or

the sharp

whistle of the golden and green plover, rising and lying, lying and

rising, as they

do on a calm night. There were a thousand thousand bright stars shining

over his

head, and there was a little frost out, which left the grass under his

foot white

and crisp. He stood

there for an hour, for two hours, for three hours, and the frost

increased greatly,

so that he heard the breaking of the traneens under his foot as

often as

he moved. He was thinking, in his own mind, at last, that the

sheehogues would not

come that night, and that it was as good for him to return back again,

when he heard

a sound far away from him, coming towards him, and he recognised what

it was at

the first moment. The sound increased, and at first it was like the

beating of waves

on a stony shore, and then it was like the falling of a great

waterfall, and at

last it was like a loud storm in the tops of the trees, and then the

whirlwind burst

into the rath of one rout, and the sheehogues were in it. It all

went by him so suddenly that he lost his breath with it, but he came to

himself

on the spot, and put an ear on himself, listening to what they would

say. Scarcely

had they gathered into the rath till they all began shouting, and

screaming, and

talking amongst themselves; and then each one of them cried out: "My

horse,

and bridle, and saddle! My horse, and bridle, and saddle!" and Guleesh

took

courage, and called out as loudly as any of them: "My horse, and

bridle, and

saddle! My horse, and bridle, and saddle!" But before the word was well

out

of his mouth, another man cried out: "Ora! Guleesh, my boy, are you

here with

us again? How are you getting on with your woman? There's no use in

your calling

for your horse to-night. I'll go bail you won't play such a trick on us

again. It

was a good trick you played on us last year?" "It

was," said another man; "he won't do it again." "Isn't

he a prime lad, the same lad! to take a woman with him that never said

as much to

him as, 'How do you do?' since this time last year!" says the third man. "Perhaps

be likes to be looking at her," said another voice. "And

if the omadawn only knew that there's an herb growing up by his

own door,

and if he were to boil it and give it to her, she'd be well," said

another

voice. "That's

true for you." "He

is an omadawn." "Don't

bother your head with him; we'll be going." "We'll

leave the bodach as he is." And with

that they rose up into the air, and out with them with one roolya-boolya

the way they came; and they left poor Guleesh standing where they found

him, and

the two eyes going out of his head, looking after them and wondering. He did

not stand long till he returned back, and he thinking in his own mind

on all he

saw and heard, and wondering whether there was really an herb at his

own door that

would bring back the talk to the king's daughter. "It can't be," says

he to himself, "that they would tell it to me, if there was any virtue

in it;

but perhaps the sheehogue didn't observe himself when he let the word

slip out of

his mouth. I'll search well as soon as the sun rises, whether there's

any plant

growing beside the house except thistles and dockings." He went

home, and as tired as he was he did not sleep a wink until the sun rose

on the morrow.

He got up then, and it was the first thing he did to go out and search

well through

the grass round about the house, trying could he get any herb that he

did not recognise.

And, indeed, he was not long searching till he observed a large strange

herb that

was growing up just by the gable of the house.  He went

over to it, and observed it closely, and saw that there were seven

little branches

coming out of the stalk, and seven leaves growing on every branches of

them; and

that there was a white sap in the leaves. "It's very wonderful," said

he to himself, "that I never noticed this herb before. If there's any

virtue

in an herb at all, it ought to be in such a strange one as this." He drew

out his knife, cut the plant, and carried it into his own house;

stripped the leaves

off it and cut up the stalk; and there came a thick, white juice out of

it, as there

comes out of the sow-thistle when it is bruised, except that the juice

was more

like oil. He put

it in a little pot and a little water in it, and laid it on the fire

until the water

was boiling, and then he took a cup, filled it half up with the juice,

and put it

to his own mouth. It came into his head then that perhaps it was poison

that was

in it, and that the good people were only tempting him that he might

kill himself

with that trick, or put the girl to death without meaning it. He put

down the cup

again, raised a couple of drops on the top of his finger, and put it to

his mouth.

It was not bitter, and, indeed, had a sweet, agreeable taste. He grew

bolder then,

and drank the full of a thimble of it, and then as much again, and he

never stopped

till he had half the cup drunk. He fell asleep after that, and did not

wake till

it was night, and there was great hunger and great thirst on him. He had

to wait, then, till the day rose; but he determined, as soon as he

should wake in

the morning, that he would go to the king's daughter and give her a

drink of the

juice of the herb. As soon

as he got up in the morning, he went over to the priest's house with

the drink in

his hand, and he never felt himself so bold and valiant, and spirited

and light,

as he was that day, and he was quite certain that it was the drink he

drank which

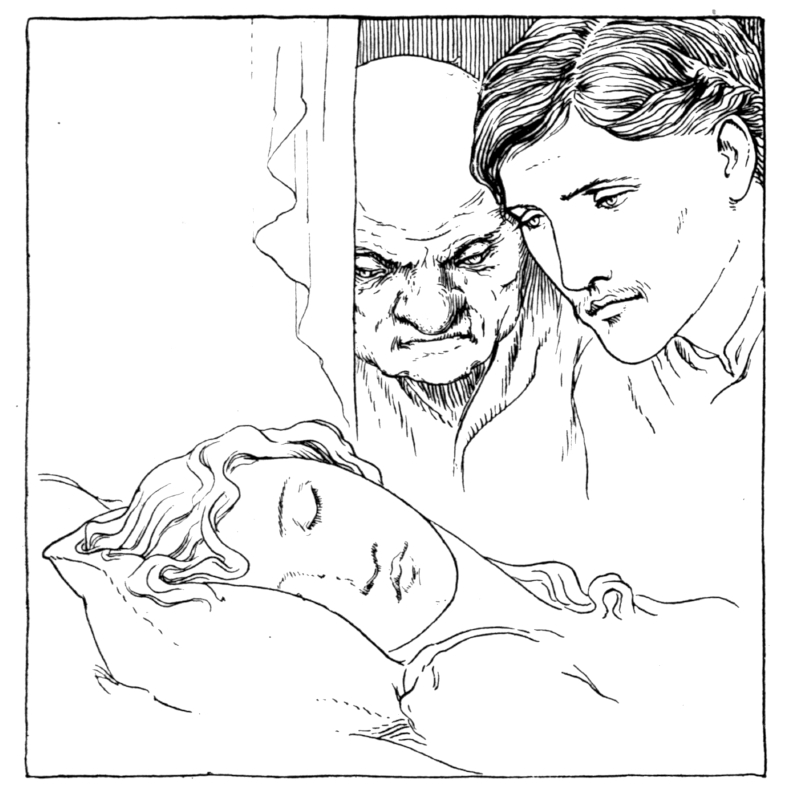

made him so hearty. When he

came to the house, he found the priest and the young lady within, and

they were

wondering greatly why he had not visited them for two days. He told

them all his news, and said that he was certain that there was great

power in that

herb, and that it would do the lady no hurt, for he tried it himself

and got good

from it, and then he made her taste it, for he vowed and swore that

there was no

harm in it.  Guleesh

handed her the cup, and she drank half of it, and then fell back on her

bed and

a heavy sleep came on her, and she never woke out of that sleep till

the day on

the morrow. Guleesh

and the priest sat up the entire night with her, waiting till she

should awake,

and they between hope and unhope, between expectation of saving her and

fear of

hurting her. She awoke

at last when the sun had gone half its way through the heavens. She

rubbed her eyes

and looked like a person who did not know where she was. She was like

one astonished

when she saw Guleesh and the priest in the same room with her, and she

sat up doing

her best to collect her thoughts. The two

men were in great anxiety waiting to see would she speak, or would she

not speak,

and when they remained silent for a couple of minutes, the priest said

to her: "Did

you sleep well, Mary?" And she

answered him: "I slept, thank you." No sooner

did Guleesh hear her talking than he put a shout of joy out of him, and

ran over

to her and fell on his two knees, and said: "A thousand thanks to God,

who

has given you back the talk; lady of my heart, speak again to me." The lady

answered him that she understood it was he who boiled that drink for

her, and gave

it to her; that she was obliged to him from her heart for all the

kindness he showed

her since the day she first came to Ireland, and that he might be

certain that she

never would forget it. Guleesh

was ready to die with satisfaction and delight. Then they brought her

food, and

she ate with a good appetite, and was merry and joyous, and never left

off talking

with the priest while she was eating. After

that Guleesh went home to his house, and stretched himself on the bed

and fell asleep

again, for the force of the herb was not all spent, and he passed

another day and

a night sleeping. When he woke up he went back to the priest's house,

and found

that the young lady was in the same state, and that she was asleep

almost since

the time that he left the house. He went

into her chamber with the priest, and they remained watching beside her

till she

awoke the second time, and she had her talk as well as ever, and

Guleesh was greatly

rejoiced. The priest put food on the table again, and they ate

together, and Guleesh

used after that to come to the house from day to day, and the

friendship that was

between him and the king's daughter increased, because she had no one

to speak to

except Guleesh and the priest, and she liked Guleesh best. So they

married one another, and that was the fine wedding they had, and if I

were to be

there then, I would not be here now; but I heard it from a birdeen that

there was

neither cark nor care, sickness nor sorrow, mishap nor misfortune on

them till the

hour of their death, and may the same be with me, and with us all!

|

here

was once a boy in the County Mayo; Guleesh was his name. There was the

finest rath

a little way off from the gable of the house, and he was often in the

habit of seating

himself on the fine grass bank that was running round it. One night he

stood, half

leaning against the gable of the house, and looking up into the sky,

and watching

the beautiful white moon over his head. After he had been standing that

way for

a couple of hours, he said to himself: "My bitter grief that I am not

gone

away out of this place altogether. I'd sooner be any place in the world

than here.

Och, it's well for you, white moon," says he, "that's turning round,

turning

round, as you please yourself, and no man can put you back. I wish I

was the same

as you."

here

was once a boy in the County Mayo; Guleesh was his name. There was the

finest rath

a little way off from the gable of the house, and he was often in the

habit of seating

himself on the fine grass bank that was running round it. One night he

stood, half

leaning against the gable of the house, and looking up into the sky,

and watching

the beautiful white moon over his head. After he had been standing that

way for

a couple of hours, he said to himself: "My bitter grief that I am not

gone

away out of this place altogether. I'd sooner be any place in the world

than here.

Och, it's well for you, white moon," says he, "that's turning round,

turning

round, as you please yourself, and no man can put you back. I wish I

was the same

as you."