A babe is in the Indian's

hut,

A babe but lately born,

And yet the dwelling is not

shut,

At noon, or night, or morn,

But heat and cold, and light

and air,

The little stranger learns

to bear.

And daily in the stream or

flood

The tender child is bathed,

And daily to a piece of wood,

With bandage closely

swathed;

That spreading joint, or

crooked limb,

May not deform and trouble

him.

And when the mother goes

abroad,

And bears her infant young,

Still fastened to this piece

of board,

Upon her back 'tis hung;

Through summer's heat and

winter's snow,

For many a mile they travel

so.

Sometimes in basket sleeping

laid,

'Twas hung upon a tree,

The wind a lulling music

made,

And rock'd it merrily;

Hard by, her work the mother

plied,

And listened when it waked

or cried.

She made no garment thick or

thin,

Its person to array;

No cap was tied beneath its

chin,

Bedeck'd with ribbons gay,

And not a single frill of

lace,

Was round the Indian baby's

face.

And yet it eat, and drank

and slept,

And grew as fast and strong,

As if in splendid chamber

kept,

By servants tended long,

Perhaps the little Indian,

too,

As mindful of its parents

grew.

For as we read, of lash or

thong

But little use was made,

And yet the aged, by the young,

Were reverenced and obeyed;

And in this day 'twere not

amiss,

For all to heed and copy

this.

To the forest fine, where

the oak and pine

With spreading branches

grew,

In days of old, came the

Indian bold,

Who wanted a canoe.

When his practised eyes, a

tree espies

Of proper size and strength,

With ready blow he lays it

low,

And hews to proper length.

All this is done with axe of

stone,

And arm of labor stout;

But 'twill now require the

aid of fire,

The trunk to hollow out.

With careful hands the

glowing brands

On the russet bark are laid,

And watched and turned, till

the core is burn'd,

And the needful hollow made.

His boat thus made, from the

forest's shade

The Indian bears with pride,

And with paddle good of

oaken wood,

Impels it o'er the tide.

Unlike indeed, in form and

speed,

Was the Indian's poor canoe,

To the pinnace gay, which

now each bay

And harbor brings to view.

And every lad may well be

glad

As he sails in vessel trim,

That this early day hath

passed away,

And a better risen for him,

THE HUNTER

His food was scant, his

venison gone,

And he must hunt perchance

all day,

E'er he his hunger can

allay.

His bow the hunter closely

eyes,

Its string of twisted sinews

tries;

Since steel or iron he had none,

His arrow heads were

sharpened stone.

With these equipped, and

round him tied

His garments of the dun

deer's hide,

He from his wigwam's opening

came,

With steps erect and sturdy

frame.

True to his purpose, all the

day

He ranged the forest for his

prey,

Nor sought alone the

antler'd deer

And tender fawn to make him

cheer.

The hunter knew how sweet

and fresh,

Was rabbit's and was

squirrel's flesh;

Nor lightly was esteemed by

him,

The woodchuck and the

weasel's limb.

The sun was in the western

sky,

His children with impatient

eye,

Had long looked out, in

hopes to greet

The hunter's home returning

feet.

His form is seen, and shout

and whoop

Come loudly from the merry

troop,

For meat beside, he seldom

fails

To bring them fox and

squirrel's tails.

Now nearer come, his

gladsome squaw

A fresh supply of venison

saw;

For one fine deer, with

smaller game,

The victims of the chase

became.

Now placed within the

wigwam's bounds,

The impatient group the food

surrounds,

And the brisk wife prepares

to dress,

In fashion rude her evening

mess.

You who would learn the way

they took,

With neither pot nor pan to

cook,

May read the next-ensuing

verses,

Which Indian cookery

rehearses.

No little girl or boy hath

guess'd

The process or the art,

By which the early Indians

dress'd

And cut their meat apart;

Since neither knife, nor

spoon, nor fork,

Had they to aid them in

their work.

A piece of flint or

sharpen'd shell,

The place of knife supplied,

And answered every purpose

well,

To free it from the hide,

To clear the entrails,

scrape the hair,

And make the carcass clean

and fair.

Then in the earth a pit was

made,

To hold the fish or game,

With stones at side and

bottom laid,

An oven soon became:

No better did their wants

require

And here they lighted up a

fire.

From this when gained

sufficient heat,

The glowing coals were dug.

And here deposited the meat,

With leaves encompass'd

snug;

With heated stones 'twas

covered up,

Till time to breakfast,

dine, or sup.

But how without a pot to

boil,

Must puzzle Indian wit;

A stone they sought, and mighty

toil

A hollow made in it,

And water got its warmth

alone

From heated pebbles in it

thrown.

And other pebbles burning

hot,

Kept up the boiling heat,

Within this strangely

fashioned pot,

And here they cooked their

meat;

Not over nice, for Indian

eye

Beheld not dainty cookery.

And fish well broiled on

embers red,

The Indians often saw,

And shell-fish from their

rocky bed,

Were eaten roast and raw:

Yet poor the viands Indians

prized

Would seem to people

civlized.

THE WARRIOR

Bade all his brave warriors

be ready for fight;

Some neighboring tribe had

his people annoyed,

Their wigwams had plundered,

or corn had destroyed.

Then up rose each warrior,

his tomahawk tried,

His bow and his arrows most

carefully eyed,

And soon to the gathering

came in a fierce throng,

To join in the war dance and

sing the war song.

The song and the dance, how

unlike was the tune

And the motion, to that of

the hall and saloon;

They sung in wild screams

how their foes they'd engage,

And the dance was but

gestures of fury and rage.

And then with her paint an

old woman came in,

To daub every warrior from

forehead to chin,

They imagined their foemen

would view them with dread,

When each was made hideous

with black, white and red.

These colors the matron at

random disposes,

On cheeks and on foreheads,

on eyelids and noses,

Their hair long and lank in

a close knot she gathers,

And sticks in the centre a

bunch of gay feathers.

A small stock of corn which

the women must parch,

Is all the provision they

make for their march;

And with little farewell to

wife, parent or daughter,

The war-party goes on its

errand of slaughter.

I follow them not where the

battle arose,

I tell not of scalped or of

tomahawk'd foes:

The deeds of their arms are

too sad for my story,

For war they call'd

pleasure, and cruelty glory.

"I do not like this

frock of mine,"

Said little Ellen to her

mother;

"The girls at school are dress'd so fine,

I wish you would get me

another.

"And will you get one

very gay,

And a new bonnet trim'd with

lace,

That I may look as smart as

they,

Nor be ashamed to show my

face!"

Her mother answered her,

"My dear Your clothes,

I'm sure, are very good,

Nor would I wish you to

appear

So fine and gaudy if you

could.

"But if you'll love

your studies, child,

I'll buy you many pretty books;

And be good-natur'd, kind

and mild,

And all your friends will

like your looks,"

We love the town in wintry

weather,

Here houses are all close

together,

When not a single leaf of

green,

Is in the fields or gardens

seen;

But when summer comes so

warm,

What so pleasant as a Farm,

O how children love to play,

Where the men are raking

hay;

Now with baskets see them

go,

Where the grapes or berries

grow.

In the orchard next you'll

see

Them picking fruit from tree

to tree,

What lovely apples, pears

and plums,

Hang on the trees when

autumn comes.

Little friends who yet have

left

Grandmothers whom age

endears;

Little friends who are

bereft

Of this joy of early years,

Unto me your ears incline,

While I fondly tell of mine.

Memory yet delights to view,

Hours of infantine delight,

When her high-heeled velvet

shoe,

With its silver buckle

bright,

Gave her grandchild greater

joy,

Than the most expensive toy.

Half my joy cannot be told,

When from pockets deep and

wide,

Treasures new and treasures

old,

Lay commingled side by side,

All my admiration won,

E'en her worsted pin

cushion.

Other charms, as years went

by,

In this lov'd one could I see;

Soon I noticed that her eye

Sent her fondest glance to

me;

None like her had healing

skill,

When her little girl was

ill.

Then her cap of cambric fine

Cover'd locks as white as

snow,

These my fingers oft would

twine,

While her neck they

compass'd slow,

Every golden bead to tell,

Though I knew their number

well.

Others painted for my

choice,

Good and evil deed and

thought,

But my own grandmother's

voice,

To my heart their lessons

brought;

For that heart had confidence,

In her wisdom, love, and

sense.

I have seen since I was

young,

Many a year of care and

strife;

But the precepts of her

tongue,

And the lessons of her life,

Still have power my feet to

stay,

From a tempting evil way.

Since the time that she was

born,

More than eighty years had

passed,

Like a shock of ripen'd

corn,

To the grave she sunk at

last,

And we humbly trust found

rest,

With the spirits of the

blest.

'Tis twilight when the

glorious sun,

Has left his place on high,

When evening shades have

just begun

To steal along the sky.

The swallow leaves the

fields of air,

The busy bee the flower,

And busier man is glad to

share,

The quiet of the hour.

Tho' small in size, the

cricket tries,

His voice so shrill and

strong,

And many a frog from pond

and bog,

Sends forth its croaking

song.

'Tis now the time when

children dear

May rest their wearied

limbs,

And as the time for bed draws near,

Repeat their evening hymns.

Too dark to read, if now

should fail

Their little stock of verse,

May listen to some pleasant

tale,

Which others can rehearse.

For one dear boy, who loved

the power

Of twilight's quiet time,

A friend belov'd, in leisure

hour

Composed this book of rhyme.

For at the close of every

day,

Did Thomas seek this friend,

To ask for some amusing lay,

Which she had heard or

penn'd.

If good and gentle was the

boy,

Her arms she round him

threw,

And from her memory drew

with joy,

Her stories old and new.

But if departing from the

right,

His deeds had been amiss,

No twilight tale had he that

night,

Or pleasant parting kiss.

And here behold in fair

array,

A part of this her work,

Printed and sold by Mahlon

Day,

Who lives in famed New-York.

In Pearl-street stands his

handsome store,

The number we affix,

In figures marked above the

door,

Three hundred seventy-six.

THE INDIAN AND THE PLANTER

By the door of his house a

planter stood,

In fair Virginia's clime,

When the setting sun had

tinged the wood

With its golden hue sublime.

The lands of this planter were

broadly spread,

He lacked not gold or gear,

And his house had plenty of

meat and bread

To make them goodly cheer.

An Indian came from the

forest deep,

A hunter in weary plight,

Who in humble accents asked

to sleep

'Neath the planter's roof

that night.

To the Indian's need he took

no heed,

But forbade his longer stay:

"Then give me," he

said, "but a crust of bread,

"And I'll travel on my

way."

In wrath the planter this

denied,

Forgetting the golden rule;

"Then give me, for

mercy's sake," he cried,

"A cup of water cool.

"All day I have

travel'd o'er fen and bog,

"In chase of the

bounding deer;"

"Away," cried the

planter, "you Indian dog,

"For you shall have

nothing here."

The Indian turned to his

distant home,

Though hungry and travel

sore,

And the planter enter'd his

goodly dome,

Nor thought of the Indian

more.

When the leaves were sere,

to chase the deer,

This self same planter went,

And bewildered stood, in a

dismal wood,

When the day was fully

spent.

He had lost his way in the

chase that clay,

And in vain to find it

tried,

When a glimmering light fell

on his sight,

From a wigwam close beside.

He thither ran, and a savage

man

Received him as a guest;

He brought him cheer, the

flesh of deer,

And gave him of the best.

Then kindly spread for the

white man's bed,

His softest skins beside,

And at break of day, through

the forest way,

Went forth to be his guide.

At the forest's verge, did

the planter urge,

His service to have paid,

But the savage bold refused

his gold,

And thus to the white man said:

"I came of late to the

white man's gate,

"And weary and faint

was I,

"Yet neither meat, nor

water sweet,

"Did the Indian's wants supply.

"Again should he come

to the white man's home,

"My service let him

pay,

"Nor say again to the

fainting man,

"You 'Indian dog,

away!' "

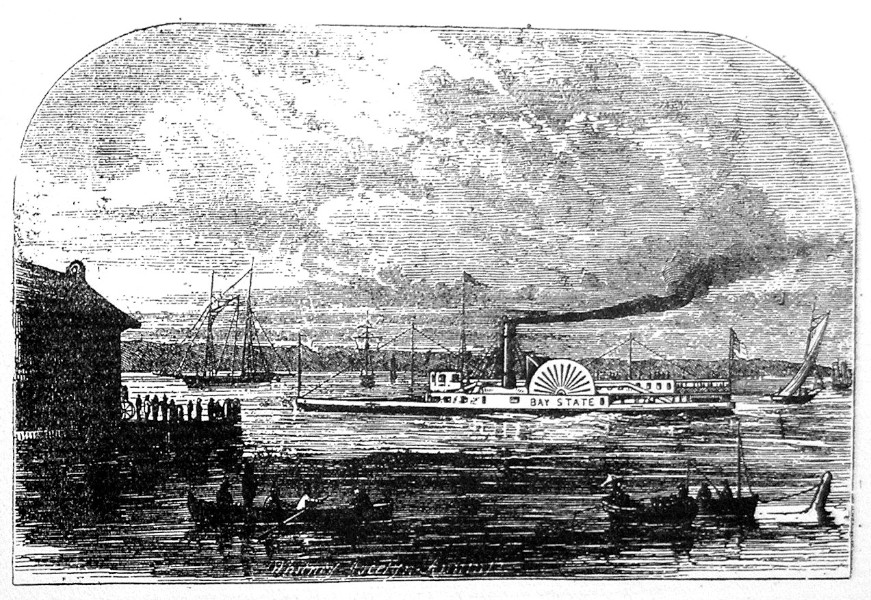

THE ACCIDENT

Said Robert to some idle

boys,

"We will see all the

passengers land on the wharf,

And hear all the clatter and

noise."

Away they all ran, with Bob

at their head,

Whom his parents thought

safe in the school;

Oh! how 't would have

griev'd them to know that instead,

He was idling and playing

the fool.

So speedily over the

Steam-boat he went,

He tri'd every passage and

stair,

Through this room and that

room his footsteps he bent,

For nobody knew he was

there.

And when the machinery came

in his view

Of this thing and that thing

he feels

And thought not of danger,

for little lie knew

The terrible power of the

wheels.

But as he was turning from

what he had seen,

To view something else that

was near,

His foot was caught fast in

the dreadful machine,

As it rolled in its rapid

career.

He screamed till they heard

him and stopp'd the great wheel,

Then up to the deck he was

borne,

But sad to relate, from his

toe to his heel

Was dreadfully mangled and

torn.

The poor little fellow was

put in the chair,

And conveyed to his own father's door;

A surgeon was sent for, who

dress'd it with care,

But the blood ran in streams

to the floor.

Long he lay on his bed,

where he suffer'd so much,

That his folly he deeply

deplores,

And through all his life

must he walk with a crutch,

With which he just hobbles

out doors.

Little boys, have a care,

and keep close to your homes

Nor pleasures forbidden

pursue,

Not only yourselves, but

when punishment comes,

All who love you must suffer

with you.

Little boys, have a care,

'tis our Father in Heaven,

Who has bless'd us with life

and with limb,

And to carelessly trifle with what he hath given,

Is surely displeasing to

him.

A LITTLE BOY WHO BROKE HIS

ARM

A little happy boy, one day,

Jump'd up into a chair to

play,

Not thinking any harm;

When, O how sad! I grieve to

tell,

Down came the chair, and

William fell

And broke his little arm.

Poor little fellow, how he

cried,

His mother grieved, and all

beside

Who heard what had been

done:

A tedious time he had to

wait,

Until the doctor set it

straight,

And put the splinters on.

His mother held him all the

while,

And pleased was she to see

him smile,

When all the pain was o'er,

When on his bed he sweetly

slept,

'Twas then she sat her down

and wept,

Till she could weep no more.

He suffer'd much before

'twas set,

But still he did not scream

and fret,

As many would have done:

All lov'd him more than words

can tell,

Because he did behave so

well,

With such a broken bone.

His father, aunts, and

cousins too,

All brought him sweetmeats

not a few,

He was so good a child:

Then little children don't

you see,

How happy 'tis for one to be

So gentle, and so mild.

"A HAPPY NEW YEAR"

I wish you all a happy year!

The most industrious, it is

true,

Will always be the happiest

too—

If little fingers fast will

fly,

There'll be no time to fret

and sigh;

And if the head have full

employ,

The heart will always dance

with joy.

If good and active, children

dear,

You're sure to have a happy

year.

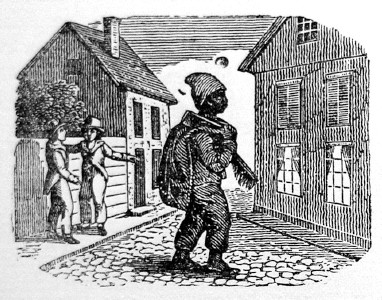

THE CHIMNEY SWEEP

With sooty clothes tatter'd and torn?

An old cap on his head, but

no shoes on his feet,

O surely he looks most

forlorn!

O why don't his mother take

off his old clothes,

And wash him and dress him

up neat?

He scares all the children wherever he goes,

A screaming so loud in the

street.

O don't be afraid of the

poor little boy,

Because he is ragged and

black;

I dare say his mother

beholds him with joy,

And calls him her poor

little Jack.

He's oblig'd to sweep

chimneys to earn her some bread,

Because she is feeble and

poor,

With the money he earns all

the children are fed,

Then Jack's a good boy I am

sure.

And he has no father, he

died long ago,

When Jack was a very small

boy:

O then do not wonder to see

him look so,

And have not a better

employ.

And boys should not call him

a dunce and a fool,

Because the poor Sweep-O

could not go to school.

Note,—Little colored boys in

cities used to find employment sweeping out chimneys, They went about the

streets with their brushes calling out "Sweep-O, Sweep-O," much the

same as newsboys now call out their papers.

For those who have fathers

and mothers to feel,

A grief in their follies, a

joy in their weal,

But sometimes forget the

obedience their due,

This story is written as sad

as 'tis true.

A kind hearted Lady, a

friend to the poor,

One bitter cold morning

beheld at her door,

A poor little fellow, his

jacket was thin,

And the rags called his

trowsers scarce cover'd his skin.

She spoke to the child in a

compassionate tone,

And found he subsisted by

begging alone,

He early was forced for his

living to strive,

For of years he yet wanted

some months to be five.

Yet bright and intelligent

Willy appear'd,

Surpassing far many more

tenderly rear'd;

His father, a soldier, was

gone from the state,

And three little children

were left with his mate.

This mother of Willy's, the

neighbors all thought,

Spent a good deal more money

in gin than she ought,

While he and his sister

asked victuals and wood,

The poor little baby made

out as it could.

When marked by the blows

which her anger inspired,

Thus Willy excused her to

all that inquired:

Mother said I was saucy, and

missing the place

Where her hand meant to

strike me, it fell on my face.

His kind benefactress did

all that she could,

She fed him, she clothed

him, advised him for good,

He must beg for his mother

as long as 'tis cool,

But when the spring comes

she will send him to school.

But you who have fathers and

mothers to feel,

A grief in your follies, and

joy in your weal,

Remember, I pray you, how

much is their due,

Lest poor little Will should

be better than you.

|

|