| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

PART

III.

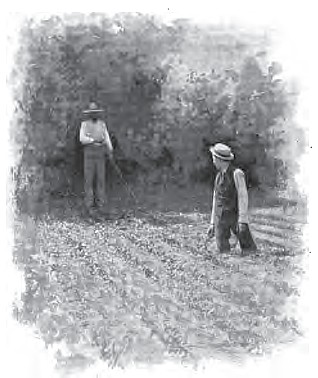

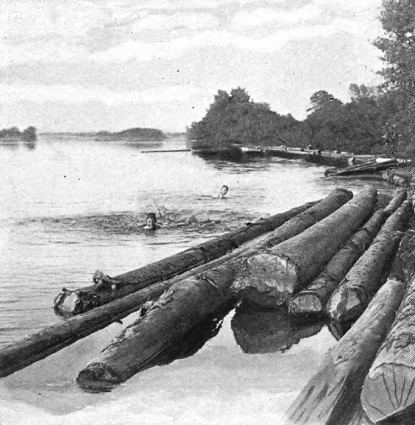

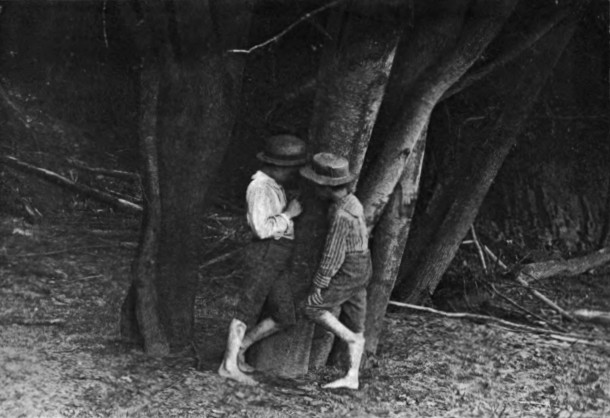

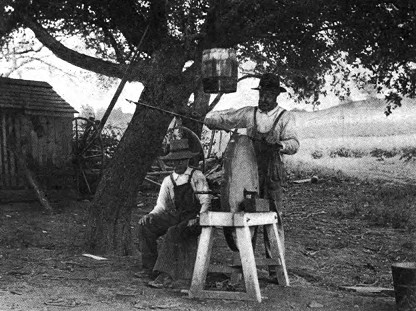

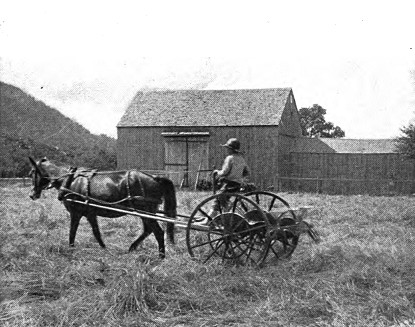

SUMMER. THE boy feels that summer has really come about the time he gets a new straw hat and begins to go barefoot. When he first gets on the earth without shoes and stockings he is as frisky as are the cows when, after the winter's sojourn in the barn, they are let out to go to pasture for the first time. The boy remembers very well how he nearly ran his legs off on that occasion, for the cows wanted to career all through the neighborhood, and they kicked and capered and ran and hoisted their tails in the air, and were as bad as a circus broke loose. The boy would have gone barefoot some weeks before, only he could not get his mother to understand how warm the earth really was. It is cooler now than he thought, but he gets into a glow running, and in a few days the exposure toughens his feet so that he can stand almost anything — anything but shoes and stockings. He hates to put those uncomfortable things on, and, when he does, is glad to kick them off at the earliest opportunity. Even the first frosts of autumn do not at once bring the shoes out. He will drive the cows up the whitened lane, and slip shivering along in the tracks brushed half clear of frost by the herd, certain that he will be entirely comfortable a little later when the sun gets well up. But the joy of bare feet is not altogether complete even in summer. About half the time the boy goes with a limp. He has hurt his toe, cut his heel, or met with some like mishap. There is something always lying around for him to step on, and in the late summer certain wicked burs ripen in the meadow that have hooks to their prickles, that hurt enough going in, but are, oh, so much worse pulling out! The boy never likes to walk on newly mown land on account of the stiff grass stubs that cover it. Yet he can manage pretty well by sliding his feet along and making the stubble lie flat when he steps on it. However, the gains of bare feet certainly much more than offset the losses, to his mind; for he can tramp and wade almost everywhere and in all kinds of weather, with no fear of tearing his stockings, muddying his shoes, or "getting his feet wet."  Advising the hired boy He appreciates this going barefoot most, perhaps, after a rain storm. You have no idea, unless you have been a boy yourself, what fun it is to slide and spatter through the pools and puddles of the roadway. There is the boy's mother, for instance — she fails to have the mildest kind of appreciation of it. She has even less, if that is possible, when the boy comes in to her after he has astonished himself by a sudden slip that seats him in the middle of one of these puddles.  Waiting for the dinner horn When the air, after a storm, is very still, the boy is sometimes impressed by the apparent depth of these shallow pools. They seem to go down miles and miles, and he can see the clouds and sky reflected in their clear deeps. He is half inclined to keep away from their edges, lest he should fall over and go down and down till he was drowned among those far-off cloud reflections. Another roadway sentiment the boy sometimes entertains is connected with the ridges of dirt thrown up by the wagon-wheels. Their shadows make pictures to him as of a great line of jagged rocks — like the wild coast of Norway in his geography. He feels like an explorer as he follows the ever-changing craggedness of their outlines. I mentioned that the boy had a new straw hat with the beginning of summer. You would not think it two days afterward. It had by then lost its store manner and had taken to itself an individual shape all its own. It did not take long for the ribbon to begin to fly loose on the breezes, and then the colt took a bite out of the edge, and a general dissolution set in. The boy used it to chase grasshoppers and butterflies with, and one day he brought it home half full of strawberries he had picked in a field. On another occasion he utilized it to catch pollywogs in when he was wading, and he hastened its ruin by using it as a ball on summer evenings to throw in the air. He thought, one night, he had put it past all usefulness when, not thinking where he had placed it, he went and sat down in the chair where it was. You would not have known it for a hat when he picked it up, though he straightened it out after a fashion and concluded it would serve for a while longer, anyway. But things presently got to that desperate pass where the brim was gone and there was a bristly hole in the top, and "the folks" saw the hat could not possibly last the summer through, and the next time his father went to town he bought the boy a new one. Of course, he told him to be more careful with this than with the old one, when he gave it to him.  Eating clover blossoms The summer was not far advanced when the boy became anxious as to whether the water had warmed up enough in the streams to make it allowable to go in swimming. As for the little rivers among the hills, they never did get warmed up, and in the hottest spells of midsummer it made the boy's teeth chatter to jump into their cold pools. But there was a glowing reaction after the plunge, and if he did not stay in too long he came out quite enlivened by his bath, The bathing places on these woodland streams are often quite picturesque. It may be a spot where the stream widens into a little pond hemmed in by walls of green foliage, whose branches in places droop far out over the water. It may be in a rocky gorge strewn with bowlders, where the stream fills the air with a continual roar and murmur as it dashes down the rapids and plunges from pool to pool. On the large rivers of the valleys the swimming places have usually muddy shores and a willow-screened bank, and there are logs to float on or an old boat to push about. In favorable weather the boys will go in swimming every evening, and they make the air resound for half a mile about with their shouts and splashings.  In swimming June comes in with lots of work in the planting line. The boy has to drop fertilizer and drop potatoes some days from morning till night, by which time he is ready to drop himself. In corn planting he has his own bag of tarred corn and his hoe, and takes the row next to his father's. For a spell he may keep up with the rest, but as the day advances he lags behind, and his father plants a few hills occasionally on the boy's row to encourage him. One of the things a boy soon becomes an adept at is leaning on his hoe. He naturally does this most when he is alone in the field and not liable to sudden interruptions in his meditations. At such times he gets lonesome and has "that tired feeling," and gets to wondering why the dinner horn doesn't blow. You would not think a hoe an easy thing to lean on; but the boy will stand on one leg, with the hoe-handle hooked under his shoulder, for any length of time. The corn is no sooner in the ground than the crows begin to happen around to investigate. They will pull it even after it gets an inch or two high and snap off the kernel at the roots, and it seems sometimes as if they rather liked the flavor of the tar put on to destroy their appetite. The boy's indignation waxes high and he wishes he had a gun or a pistol, or something, to "fix" those old crows. His mother does not like firearms. She is afraid he will shoot himself; but she gives him some old clothes, and he goes off to the shop to tack a scarecrow together and stuff him with hay. When his father appears and pretends to be scared by the scarecrow's terrible figure, the boy is quite elated. After supper he and his mother and the smaller children go out in the field and set the man up, and the boy shakes hands with him and holds a little conversation with him. His small brothers and sisters are sure the crows won't "dast" to come around there any more, and they are kind of scared of the old scarecrow themselves.  Cutting their names in a tree-trunk The days wax hotter and hotter as the season advances, and the boy presently gets down to the simplest elements in the clothing line, Indeed, if his folks do not insist on something more elaborate, he goes about entirely content in a shirt and a pair of overalls. His hair is apt to grow rather long between the cuttings his mother gives it, and about this time he looks up an uncle or a cousin who is an adept in the hair-cutting line, and gets a tight clip that leaves him as bald as his most ancient ancestor. He feels delightfully cool, anyway, and looks don't count much with him at that age. As soon as the first plowing was done in the spring the onions were sowed. Their little green needles soon prickled up through the ground, and now they had the company of a multitude of weeds, and must be hoed and weeded out. One thing the boy never quite gets to understand is the curious fact that weeds, at first start, will grow twice as fast as any useful crop. He wishes weeds had some value. All you'd have to do would be to let them grow. They'd take care of themselves. In the case of the onions the hoeing-out part is not very bad, but when you get down on your hands and knees to scratch the weeds out of the rows with your fingers your trouble begins. The boy says his back aches. His father comforts him by telling him that he guesses not — that he's too young to have the backache — that he'd better wait till he's fifty or sixty, and his joints get stiff and he has the rheumatism; then he'll have something to talk about. But the boy knows very well that his back does ache, and the sun is as hot again as it was when he was standing up, and his head feels as if it were going to drop off. He gets up once in a while to stretch, and to see if there are any signs of his mother's wanting him at the house, or hens around that ought to be chased off, or anything else going on that will give him a chance for a change. He bends to his work again presently, and tries various changes from the plain stoop, such as one knee down and the other raised to support the chest, or a sit down in the row and an attempt to weed backward. When left to himself he takes long rests at the ends of the rows, lying in the grass on his back under the shadow of an apple tree, or he gets thirsty and goes in the house for a drink. He is afflicted with thirst a great deal when he is weeding onions, and gets cooky-hungry remarkably often, too.  Weeding onions His most agreeable respite while weeding occurs when he discovers that the neighbor's boy has come out and is at work just over the fence. He throws a lump of dirt at him to attract his attention, and then they exchange "hulloes!" They soon come together and lean on the fence and compare gardens, and likely enough get to boasting and on the borders of a quarrel before they are through. Our boy goes back to work in time, and his aches are not so severe afterward — at least, so long as he has the neighbor's boy over the fence to call at. When the boy's father goes away from home, to be gone all day, he is apt to set the boy a "stent." "You put into it, now," he says, "and hoe those eighteen rows of corn, and then you can play the rest of the day." The boy is inclined to be dubious when he contemplates his task; it doesn't look to him as if he could get it done in the whole day. But he makes a start, and concludes it is not so bad, after all. He keeps at work with considerable perseverance, and only stops to sit on the fence for a little while at the end of every other row, and once to go up the lane to pick a few raspberries that have turned almost black. As the rows dwindle he becomes increasingly exuberant, and whistles all through the last one; and when that is done, and he puts the hoe over his shoulder and marches home, he has not a care in the world. He made up his mind early in the day that he would go fishing when he was free, and now he digs some worms back of the shop, gets out his pole, and hunts up his best friend. The best friend is watering tobacco. He can't go just then, but if Tommy will pitch in and help him for about fifteen minutes, he'll have that job done and will be with him. The boys make the water fly, and it is not long before they and their poles and their tin bait-box are at the river side. The water just dimples in the light breeze. The warm afternoon sunlight shines in the boys' faces and glitters on the ripples. They conclude, after a little while, that it is not a good afternoon for fishing, and think wading will prove more profitable. As a result, they get their "pants" wet and their jackets spattered, though where on earth all that water came from they can't make out. They thought they were careful. They are afraid their mothers will make some unpleasant remarks when they get home. It seems best they should roll down their trousers and give them a chance to dry a little before they have to leave. Meanwhile they do not suffer for lack of amusement, for they find a lot of rubbish to throw into the water, and some flat stones to skip, and some lucky-bugs to catch, and lastly Charlie Thompson's spotted dog shows himself on the bank, and they entice him down to the shore and take to wading again, and have great fun, and get wetter than ever. As they walked home, Tommy said, "Let's go fishing again, some day," and Sammy agreed without any hesitation. They caught not even a shiner this time, but on some occasions they brought home a perch or two and a bullhead and a sucker, strung on a willow twig. Rainy days were those on which they were freest to go fishing, and on such days the fish were supposed to bite best. The boy seemed perfectly willing to don an old coat and an old felt hat and spend a whole drizzling morning at almost any time slopping along the muddy margin of the river. No one could accuse him of being over-fastidious.  Working out his "stent" At some time in his career the boy was pretty sure to bring home a live fish in his tin lunch-pail and turn him loose in the water-tub at the barn; and he might catch a dozen or two minnows in a pool left landlocked by a fall of the water, and put those in. He would see them chasing around in there, and the old big fish lurking, very solemn, in the darkest depths, and he fed them bits of bread and worms, and planned for them a very happy and comfortable life till they should be grown up and he was ready to eat them. But they disappeared in time, and there was not one left. The boy has an idea they must have eaten each other, and then the cow swallowed the last one. If it wasn't that, what was it?  Fishing In the early summer strawberries are ripe. They are the first berries to come that amount to anything. You can pick a few wintergreen and partridge berries on the hillsides in spring, but those hardly count. The boy always knows spots on the farm where the strawberries grow wild, and when, some early morning, he goes up with the cows and is late to breakfast, it proves he has been tramping in the pasture after berries. He has pushed about among the dew-laden tangles of the grass until he is as wet as if he had been in the river, but he is in a glowing triumph on his return over the red clusters he pulls from his hat to display to the family. Probably some farmer in the neighborhood raises strawberries for market, and pays two cents a quart for picking. If so, the boy can not rest easy till his folks agree to let him improve this chance to gain pocket money, which is a thing he never fails to be short of. He will get up at three o'clock in the morning and carry his breakfast with him in order to be on hand with the rest of the children on the field at daybreak. His eagerness cools off in a few days, and it is only with the greatest difficulty that the employer can get his youthful help to stick to the work through the season. They have eaten the berries till they are sick of them; they are tired of stooping, and. they have earned so much that their longings for wealth are satisfied. They are apt to get to squabbling about rows while picking, and to enliven the work on dull days by "sassing" one another. The proper position for picking is a stooping posture, but when the boy comes home you can see by the spotted pattern on the knees and seat of his trousers that he had made some sacrifices to comfort. The proprietor of the berry fields, and all concerned, are glad when they get to the end of the season. When the boy got up so early those June mornings he was in time to hear the air full of bird-songs as it would be at no other time through the day. What made the birds so madly happy as soon as the east caught the first tints of the coming sun? The village trees seemed fairly alive with the songsters, and every bird was doing his best to outdo the rest. Most boys have not a very wide acquaintance with the birds, but there are certain ones that never fail to interest them. The boy's favorite is pretty sure to be the bobolink — he is such a happy fellow; he reels through the air in such delight over his singing and the sunny weather. How his song gurgles and glitters! How he swells out his throat! How prettily he balances and sways on the woody stem of some tall meadow flower! He has a beautiful coat of black and white, and the boy wonders at the rusty feathers of his mate, which looks like an entirely different bird. As the season advances bobolink changes, and not for the better. His handsome coat gets dingy, and he loses his former gayety. He has forgotten almost altogether the notes of his earlier song of tumbling happiness, and croaks harshly as he stuffs himself on the seeds with which the fields now teem. Ease and high living seem to have spoiled his character, just as if he had been human. Before summer is done the bobolinks gather in companies, and wheel about the fields in little clouds preparatory to migrating. Sometimes the whole flock flies into some big tree, and from amid the foliage come scores of tinkling notes as of many tiny bells jingling. The boy sees no more of the bobolinks till they return in the spring to once more pour forth their overflowing joy on the blossom-scented air of the meadows.  A faithful follower One of the other birds that the boy is familiar with is the lark, a coarse, large bird with two or three white feathers in its tail; but the lark is too sober to interest him much. Then there is the catbird, of sleek form and slatey plumage, flitting and mewing among the shadows of the apple-tree boughs. The brisk robin, who always has a scared look and therefore is out of character as a robber, he knows very well. Robin builds a rough nest of straws and mud in the crotches of the fruit trees, and he has a habit of crying in sharp notes at sundown, as if he were afraid sorrow was coming to him in some shape. The robin has a caroling song, too, but that the boy is not so sure of separating from the music of the other birds. He always knows the woodpeckers by their long bills and the way they can trot up and down the tree trunks, bottom-side up, or anyhow. He knows the bluebird by its color and the phoebe by its song. The orioles are not numerous enough for him to have much acquaintance with, but he is familiar with the dainty nest they swing far out on the tips of the branches of the big shade trees. He sees numbers of little birds when the cherries ripen and the peapods fill out that are as bright as glints of golden sunlight. They vary in their tinting and size, but he calls them all yellow-birds, and has a poor opinion of them, for he rarely sees them except when they are stealing. Along the water courses he now and then glimpses a heavy-headed kingfisher sitting in solemn watchfulness on a limb or making a startling, headlong plunge into a pool. Along shore the sandpipers run about in a nervous way on their thin legs, always teetering and complaining, and taking fright and flitting away like a shot at the least sound. On the borders of the ponds the boy sometimes comes upon a crane or a blue heron meditating on one leg up to his knee in water. Off he goes in awkward flight, trailing his long legs behind him. On the ponds, too, the wild ducks alight in the fall and spring on their journeys South and North. There may be as many as twenty of the compact, glossy-backed creatures in a single flock, but a much smaller number is more common. The swallows, on summer days, are to be found skimming over the waters of the streams and ponds, and they make flying dips and twitter and rise and fall and twist and turn, and seem very happy. They have holes in a high bank in the vicinity, and if the boy thinks he wants to get a collection of birds' eggs he arms himself with a trowel, some day, and climbs the steep dirt bank to dig them out. The holes go in about an arm's length, and at the end is a rude little nest, and some white eggs with such tender shells that the boy breaks many more than he succeeds in carrying away. He stores such eggs as he gathers from time to time in small wooden or pasteboard boxes, with cotton in the bottoms, until too many of them get broken, when he throws the whole thing away. His interest has been destructive and temporary, and he would much better have studied in a different fashion, or turned his talent to something else.  Two who have been a-borrowing

Several other birds are still to be mentioned that get his attention. There are the humming birds, that are so small and that buzz about among the blossoms and prick them with their long bills, and poise so still on their misty wings, and have hues of rainbow in their feathers, and flash out of sight across the yard in no time when they see you. There are the barn and chimney swallows that you notice most at twilight, darting in tangled flights in upper air or skimming low over the fields in twittering alertness. How they worry the old cat as she crouches in the hayfield! Again and again they almost touch her head in their circling, but they are so swift and changeful that the cat has no chance of catching them. Then there is the kingbird the boy very much admires. He is a vigorous, well-looking fellow, with an admirable antipathy for tyrants and bullies. Size makes no difference with him. He puts the crow to ungainly flight; he follows the hawk, and you can see him high in air darting down at the great bird's back again and again; and he does not even fear the eagle. In corn-planting time the whip-poor-will makes the evening air ring with his lonely calls, and the boy has sometimes seen his dusky form standing lengthwise of a fence rail just as he was about to flit far off across the fields and renew more distantly his whistling cry. The most distressing bird of all is the little screech-owl. His tremulous and long-drawn wail suggests that some one human is out there in the orchard crying out in his last feeble agonies. To put it mildly, the boy is scared when he hears the screech-owl. The great and only holiday of the summer is Fourth of July. The boy very likely does not know or especially care what the philosophic meaning of the day is. As he understands it, the occasion is one whose first requirement is lots of noise. To furnish this in plenty, he is willing to begin the day by getting up at midnight to parade the village street with the rest of the boys, and toot horns and set off firecrackers, and liven up the sleepy occupants of the houses by making particular efforts before each dwelling. They have a care in their operations to be on guard, that they may hasten to a safe distance if any one rushes out to lecture or chastise them; but if all continues quiet within doors they will hoot and howl about for some time, and even blow up the mail-box with a cannon cracker, or commit other mild depredations, to add to the glory of the occasion. When some particularly brilliant brain conceived the idea of getting all the boys to take hold of an old mowing machine and gallop it through the dark street in full clatter, it may be supposed that the final touch was given to American independence and liberty. It was not all the boys that went roaming around thus, and it was the older and rougher ones who were the leaders. The smaller boys did not enter very heartily into all of the fun, though they dared not openly hang back; and when the stars paled and the first gray approach of dawn began to lighten the east, the little fellows felt very sleepy and lonely in spite of the company and noise. They were glad enough when, soon after, the band broke up and they could steal away home and to bed. The day itself was enlivened by much popping of firecrackers and torpedoes in farm dooryards — by a village picnic, in the afternoon, and by a grand setting off in the evening of pin-wheels, Roman candles, a nigger-chaser, and a rocket. After the rocket had gone up into the sky with its wild whirr and its showering of sparks, and had toppled and burst and burned out into blackness, the day was ended, and the boy retired with the happiness that comes from labor done and duty well performed.  The Fourth of July The work of all others that fills the summer months is haying. In the hill towns the land is stony and steep, and much of it is cut over with scythes, but the majority of New England farmers do most of their grass-cutting with mowing machines. A boy will hardly do much of the actual mowing in either case until he is in his teens; but long before that he is called on to turn the grindstone — an operation that precedes the mowing of each fresh field. He gets pretty sick of that grindstone before the summer is through. He likes to follow after the mowing machine. There is something enlivening in its clatter, and he enjoys seeing the grass tumble backward as the darting knives strike their stalks. He does not care so much about following his father when he mows with a scythe; for then he is expected to carry a fork and spread the swath his father piles up behind him. On the little farms machines are lacking to a degree, and the boys have to do much of the turning and raking by hand. Finally, they have to borrow a horse to get it in. The best-provided farmer usually does some borrowing, and there are those who are running all the time — that is, they keep the boy running; boys are made for running. The boy does not like this job very well, for the lender is too often doubtful in his manner, if not in his words.  Getting ready to mow On still summer days the hayfield is apt to be a very hot place. The hay itself has a gray glisten, and the low-lying air shimmers with the heat. It is all very well if you can ride on the tedder or rake, but it makes the perspiration start if you have to do any work by hand. You do not have to be much of a boy to be called on by your father to rake up the scatterings back of the load, and you find you have to be on the jump all the time to keep up. If you can rake, you are large enough to be on the load and tread the hay into place as it is thrown up. It is not till you are pretty well grown that you have the strength to do the pitching on. Whatever the boy does in the field, in the barn his place is up under the roof "mowing away." The place is dusky, and the dust flies, and a cricket or some uncomfortable many-legged creature crawls down your back; it is hot and stifling, and the hay comes up about twice as fast as you want it to. Before the load is quarter off you begin to listen for the welcome scratch of your father's fork on the wagon rack that signals the nearing of the bottom of the load. Even then you have to creep all around under the eaves to tread the hay more solidly. You are glad enough when you can crawl down the ladder and go into the house and give your head a soak under the pump, and get a drink of water. There's nothing tastes much better than water when you are dry that way, unless it is sweetened water that you take in a jug right down to the hayfield with you.  On the hay tedder I do not wish to give the impression that haying is made up too much of sweat and toil, and that the boy finds it altogether a season of trial and tribulation. It is not at all bad on cool days, and some boys like the jumping about on load and mow. There is fun in the jolting, rattling ride in the springless wagon to the hayfield, and when the haycocks in the orchard are rolled up for the night the boys have great sport turning somersaults over them. Then there are exhilarating occasions when the sky blackens, and from the distant horizon comes the flashing and muttering of an approaching thunderstorm. Everybody does his best then; you race the horses, and the hay is rolled up and goes, forkful after forkful, twinkling up on the load in no time. But the storm is likely to come before you have done. There is a spattering of great drops, that gives warning, and a dash of cold wind, and everybody — teams and all — will be seen racing helter-skelter to the barns. You are in luck if you get there before the whole air is filled with the flying drops. It is a pleasurable excitement, anyway, and you feel very comfortable, in spite of your wet clothes, as you sit on the meal-chest talking with the others, listening to the rolling thunder and the rain rattling on the roof and splashing into the yard from the eaves-spout. You look out of the big barn doors into the sheeted rain that veils the fields with its hurrying mists, and see its half-glooms lit up now and then by the pallid flashes of the lightning. Then comes a burst of sunlight, the rain ceases, and as the storm recedes a rainbow arches its shredded tatters. All Nature glitters and drips and tinkles. The trees and fields have the freshness of spring; the tip of every leaf and every blade of grass twinkles with a diamond drop of water. The boy runs out with a shout to the roadside puddles. The chickens leave the shelter of the sheds, and rejoice in the number of worms crawling about the hard-packed earth of the dooryard, and all kinds of birds begin singing in jubilee. But whatever incidental pleasures there may be in haying, it is generally considered a season of uncommonly hard work, and at its end the farm family thinks itself entitled to a picnic and a season of milder labor. The picnic idea usually develops into a plan to spend a whole day at some resort of picnickers, where you have to pay twenty-five cents for admission — children half price. Of course, there are all sorts of ways that you can spend a good deal more than that at these places, but it is mostly the young men, who feel called upon to demonstrate their fondness for the girls they have brought with them, that patronize the extras. The farm family is economical; it carries feed for its horses and a big lunch-basket packed full for itself, and simply goes in for all the things that are free; though Johnny and Tommy are allowed to draw on their meager supply of pocket money to the extent of five cents each for candy. There are swings to swing in and tables to eat on in a grove, and, if it is by a lake or river, there are boats to row in and fish to catch, only you can't catch them. Meanwhile the horses are tied conveniently in the woods, and spend the day kicking and switching at the flies that happen around. Toward evening the wagon is backed about and loaded up, the horses hitched into 'it, and everybody piles in and noses are counted, and off they go homeward. The sun sets, the bright skies fade, and the stars sparkle out one by one and look down on them as the horses jog along the glooms of the half-wooded, unfamiliar roadways. Some of the children get down under the seats and croon in a shaking gurgle as the wagon jolts their voices; and they shut their eyes and fancy the wagon is going backward — oh, so swiftly! Then they open their eyes, and there are the tree leaves fluttering overhead and the deep night sky above, and they see they are going on, after all. When they near home they all sit up on the seats once more and watch for familiar objects along the road. There is the house at last; the horses turn into the yard; they all alight, and in a few minutes a lamp is lighted in the kitchen. A neighbor has milked the cows. There are the full pails on the bench in the back room. The children are so tired they can hardly keep their eyes open, but they must have a slice of bread and butter all around, and a piece of pie. Then, tired but happy, they bundle off to bed.  The boy rakes after Not every excursion of this kind is to a public pleasure resort. Sometimes the family goes after huckleberries or blackberries, or for a day's visit to relatives who live in a neighboring town, or to see a circus-parade at the county seat. The family vehicle is apt to be the high, two-seated spring wagon. It is not particularly handsome to look at, but I fancy it holds more happiness than the gilded cars with their gaudy occupants that they see pass in the parade.  A summer evening game of tag The strawberries are the first heralds of a summer full of good things to eat. The boy begins sampling each in turn as soon as they show signs of ripening, and on farms where children are numerous and fruits are not, very few things ever get ripe. You would not think, to look at him, that a small boy could eat as much as he can. He will be chewing on something all the morning, and have just as good an appetite for dinner as ever. In the afternoon he will eat seventeen green apples, and be on hand for supper as lively as a cricket. Still, there are times when he repents his eating indiscretion in sackcloth and ashes. There is a point in the green-apple line beyond which even the small boy can not safely go. The twisting pains get hold of his stomach, and he has to go to his mother and get her to do something to keep him in the land of the living. He repents of all his misdeeds while the pain is on him, just as he would in a thunderstorm in the night that waked and scared him; and he says his prayers, and hopes, after all, if these are his last days, he has not been so bad but that he will go to the good place. When he gets better, however, he forgets these vows and does some more things to repent of. But that is not peculiarly a boyish trait. Grown-up people do that.  Waders—they wet their "pants" |