| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

PART

IV.

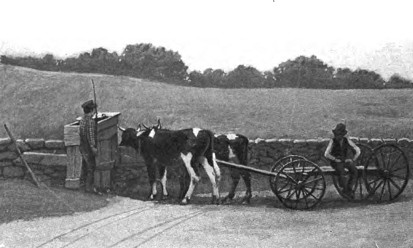

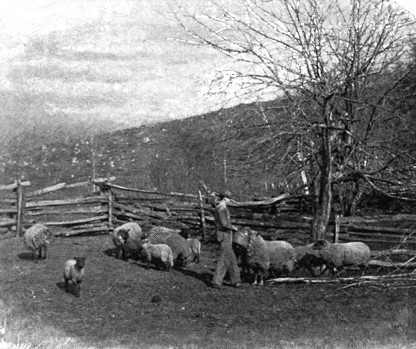

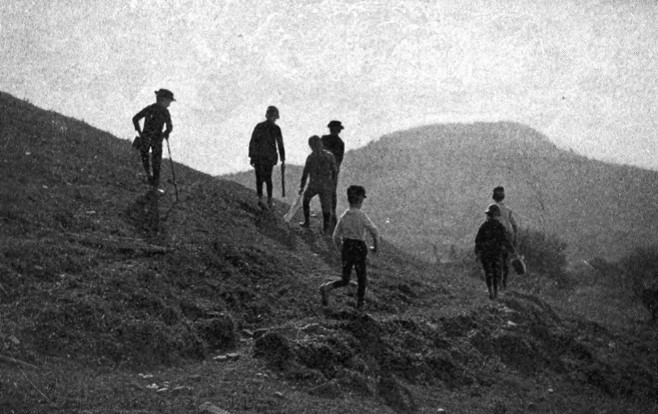

AUTUMN. BY September you begin to find dashes of color among the upland trees. It is some weakling bush, perhaps, so poorly nourished, or by chance injured, that it must shorten its year and burn out thus early its meager foliage; but as soon as you see these pale flames among the greens, you feel that the year has passed its prime. Grown people may experience a touch of melancholy with the approach of autumn. The years fly fast — another of those allotted them is almost gone; the brightening foliage is a presage of bare twigs, of frost and frozen earth, and the gales and snows of winter. This is not the boy's view. He is not retrospective; his interests are bound up in the present and the future. There is a good deal of unconscious wisdom in this mental attitude. He looks forward, whatever the time of year, with unflagging enthusiasm to the days approaching, and he rejoices in what he sees and experiences for what these things then are, and does not worry himself with allegories. The bright-leaved tree at the end of summer is a matter of interest both for its brightness and its unexpectedness. The boy will pick a branch and take it home to show his mother, and the next day he will carry it to school and give it to the teacher. He would be glad to share all the good things of life that come to him with his teacher. Next to his mother, she is the best person he knows of. He never finds anything in his wanderings about home or in the fields or woods that is curious or beautiful or good to eat but that the thought of the teacher flashes into his mind. His intentions are better than his ability to carry them out, for he often forgets himself, and eats all the berries he picked on the way home, or he gets tired and throws away the treasures he has gathered. But what he does take to the teacher is sure of a welcome and an interest that makes him happy, and more her faithful follower than ever.  A voyage on a log Summer merges so gently into autumn that it is hard to tell where to draw the line of separation. September, as a rule, is a month of mild days mingled with some that have all the heat of midsummer; but the nights are cooler, and the dew feels icy cold to the boy's bare feet at times on his morning trips to and from pasture. Yet, if you notice the fields closely, you will see, that many changes are coming in to mark the season. The meadows are being clipped of their second crop of grass; the potato tops have withered and lost themselves in the motley masses of green weeds that continue to flourish after they have ripened; the loaded apple trees droop their branches and sprinkle the earth with early fallen fruit; the coarse grasses and woody creepers along the fences turn russet and crimson, and the garden becomes increasingly ragged and forlorn. The garden reached its fullness and began to go to pieces in July. First among its summer treasures came a green cucumber, then peas and sweet corn and string beans and early potatoes. The boy had a great deal more to do with these things than he liked, for the gathering of them was among those small jobs it is so handy to call on the boy to do. However, he got not a little consolation out of it by eating of the things he gathered. Raw string beans were not at all bad, and a pod full of peas made a pleasant and juicy mouthful, while a small ear of sweet corn or a stalk of rhubarb or an onion, and even a green cucumber, could be used to vary the bill of fare. Along one side of the garden was a row of currant bushes. He was supposed to let those mostly alone, as his mother had warned him she wanted them for "jelly." But he did not interpret her warning so literally but that he allowed himself to rejoice his palate with an occasional full cluster. It was when the tomatoes ripened that the garden reached the top notch in its offering of raw delicacies. Those red, full-skinned trophies fairly melted in the boy's mouth. He liked them better than green apples. The potatoes were the hardest things to manage of all the garden vegetables he was sent out to gather for dinner. His folks had an idea that you could dig into the sides of the hills and pull out the big potatoes, and then cover up and let the rest keep on growing; but when the boy tried this and had done with a hill, he had to acknowledge that it didn't look as if it would ever amount to much afterward.  Potato-bugging The sweet-corn stalks from which the ears were picked had to be cut from time to time and fed to the cows. It was this thinning out of the corn, as much as the withering of the pea and cucumber vines and irregular digging of the potatoes, that gave the garden its early forlornness. By August the pasture grass had been cropped short by the cows, and the drier slopes had withered into brown. Thenceforth it was deemed necessary to furnish the cows extra feed from other sources of supply. The farmer would mow with his scythe, on many evenings, in the nooks and corners about his buildings or along the roadside and in the lanes, and the results of these small mowings were left for the boy to bring in on his wheelbarrow. Another source of fodder supply was the field of Indian corn. Around the bases of the hills there sprouted up many surplus shoots of a foot or two in length known as "suckers." These were of no earthly use where they were, and the boy on a small farm had often the privilege, of an afternoon, of cutting a load of these suckers for the cows. Among them he gathered a good many full-grown stalks that had no ears on them. Later there was a whole patch of fodder corn sown in furrows on some piece of late-plowed ground to gather from. He had to bring in as heavy a load as he could wheel every night, and on Saturday an extra one to last over Sunday. The cows had to have attention one way or another the year through. They were most aggravating, perhaps, when in September the shortness of feed in the pasture made them covetous of the contents of the neighboring fields. Sometimes the boy would sight them in the corn. His first great anxiety was not about the corn, but as to whether they were his folks' cows or some of the neighbors'. He would much rather warn some one else than undertake the cow-chasing himself. If his study of the color and spotting of the cows proved they were his, he went in and told his mother, then got his stick and took a bee-line across the fields. He was wrathfully inclined when he started, and he became much more so when he found how much disposed the cows were to keep tearing around in the corn or to racing about the fields in as many different directions as there were animals. He and the rest of the school had lately become members of the Band of Mercy, and on ordinary occasions he had a kindly feeling for his cows; but now he was ready to throw all sentiment overboard, and he would break his stick over the back of any one of these cows if she would give him the chance, which she very unkindly would not. He had lost his temper, and now he lost his breath, and he just dripped with perspiration. He dragged himself along at a panting walk, and he found, after all, that this did fully as well as all the racing and shouting he had been indulging in. Indeed, he was not sure but that the cows had got the notion that he had come out to have a little caper over the farm with them for his personal enjoyment. All things have an end, and in time the boy made the last cow leap the gap in the broken fence back into the pasture. They every one went to browsing as if nothing had happened, or looked at him mildly with an inquiring forward tilt of the ears, as if they wanted to know what all this row was about, anyway. The boy put back the knocked-down rails, staked things up as well as he knew how, picked some peppermint by the brook to munch on, and trudged off home. When he had drunk a quart or so of water and eaten three cookies, he began to feel himself again.  A chipmunk up a tree Besides all the extra foddering mentioned, it is customary on the small farms to give the cows, late in the year, an hour or two's baiting each day. The cows are baited along the roadside at first, but after the rowen is cut they are allowed to roam about the grass fields. Of course, it is the boy who has to watch them. There are unfenced crops and the apples that lie thick under the trees to be guarded, not to mention the turnips in the newly seeded lot, and the cabbages on the hill that will spoil the milk if the cows get them. The boundary-line fences, too, are out of repair, and the cows seem to have a great anxiety to get over on the neighbors' premises, even if the feed is much scantier than in the field where they are feeding. The boy brings out a book, and he settles himself with his back against a fencepost and plans for an easy time. The cows seem to understand the situation, and they go exploring round, as the boy says, "in the most insensible fashion he ever saw — wouldn't keep nowhere, nor anywhere else." He tries to make them stay within bounds by yelling at them while sitting where he is, but they do not seem to care the least bit about his remarks unless he is right behind them with a stick in his hand. The cows do not allow the boy to suffer for lack of exercise, and the hero in the book he is reading has continually to be deserted in the most desperate situations while he runs off to give those cows a training.  Baiting the cows by the roadside There is one of the cow's relations that the boy has a particular fondness for — I mean the calf. On small farms the lone summer calf is tethered handily about the premises somewhere out-of-doors. Every day or two, when it has nibbled and trodden the circuit of grass in its tether pretty thoroughly, it is moved to a fresh spot. The boy does this, and he feeds the calf its milk each night and morning. If the calf is very young it does not know enough to drink, and the boy has to dip his fingers in the milk and let the calf suck them while he entices it, by gradually lowering his hand, to put its nose in the pail. When he gets his hand into the milk and the calf imagines it is getting lots of milk out of the boy's fingers, he will gently withdraw them. The calf is inclined to resent this by giving a vigorous buck with his head. Very likely the boy gets slopped, but he knows well enough what to expect, not to allow himself to be sent sprawling. He repeats the finger process until in time the calf will drink alone, but he never can get it to stop bucking. Indeed, he does not try very hard, except occasionally, for he finds this butting rather entertaining, and sometimes he does not object to butting his own head against the calf's. He and the calf cut many a caper together before the summer is through. Things become most exciting when the calf gets loose. It will go galloping all about the premises. It has no regard for the garden or the flower plants, or the linen laid out on the grass to dry. It makes the chickens squawk and scamper, and the turkeys gobble and the geese gabble. Its heels go kicking through the air in all sorts of positions, its tail is elevated like a flag-pole, and there is a rattling chain hitched to its neck that is jerking along in its company. The calf is liable to step on this chain, and then it stands on its head with marvelous suddenness. The women and girls all come out to save their linen and "shoo" the calf off when it approaches the flowers, but it is the boy that takes on himself the task of capturing the crazy animal. The women folks seem much distressed by the calf's performances, while the boy is so overcome with the funniness of his calf that he is only halfway effective in his chasing. At last the calf apparently sees something it never noted before; for it comes down on its four legs stock still and stretches its ears forward as if in great amazement. Now is the boy's chance. He steals up and grabs the end of the chain; but at that moment the calf concludes that it sees nothing worthy of astonishment, and starts off again full tilt, trailing a small boy behind, whose twinkling legs never went so fast before and it is a question if things are not in a more desperate state than they were previously. By this time the boy's father and a few of the neighbors' boys appear on the scene, and between them all the calf gets confused, and allows himself to be tethered once more in the most docile subjection. You would not think the gentle little creature, who is so mildly nibbling off the clover leaves, was capable of such wild doings. On farms where oxen are used the boy is allowed to bring up and train a pair of steers. While the training is going on you can hear the boy shouting out his threats and commands from one end of the town to the other. Even old Grandpa Smith, who has been deaf as a stone these ten years, asked what the noise was about when our boy began training steers. By dint of his shoutings and whackings it was no great time before the boy had the steers so that they were quite respectable. He got them so they would turn and twist according to his directions almost any way, and he could make them snake the clumsy old cart he hitched them into over any sort of country he pleased. He trained them so they would trot quite well, too. Altogether, he was proud of them, and believed they would beat any steers in the county clean out of sight. He was going to take them to the cattle-show some time and see if they would not.  The boys and their steers Cattle-show comes in the autumn, usually about the time of the first frosts. There is some early rising among the farmers on the morning of the great day, for they must get their flocks under way promptly or they will be late. Every kind of farm creature has its place on the grounds; and in the big hall are displayed quantities of fruits and vegetables that are the biggest and best ever seen, and samples of cooking and samples of sewing, and a bedquilt, that an old lady made after she was ninety years old, that has about a million pieces in it; and another one that Ann Maria Totkins made, who is only ten years old, that has about nine hundred thousand pieces in it; and a picture in oils that this same Ann Maria Totkins painted; and some other paintings, and lots of fancy things, and all sorts of remarkable work that women and girls can do and a boy isn't good for anything at. However, the boy admires all this handiwork, and is astonished at the big squash that grew in one summer and weighs twice as much as he does, and surveys the fruits with watery mouth, and exclaims, when he gets to the potatoes, any one of which would almost fill a quart measure, "Jiminy! wouldn't those be the fellers to pick up, though?" "I don't think you use very nice language," says Eddie's older sister, who is nearly through the high school. "Well, you don't know much about picking up potatoes," is Eddie's retort. There are more chances to spend money than you can "shake a stick at" on the cattle-show grounds. All sorts of men are walking around through the crowd with popcorn and candies, and gay little balloons and whistles and such things to sell, and there are booths where you can see how much you can pound and how much you can lift and how straight you can throw an egg at a "nigger's" head stuck through a canvas two rods away. There are shooting galleries, and there is a phonograph, where you tuck some little tubes into your ears and can hear the famous baritone, Augustus William de Monk, sing the latest songs, and it is so funny you can not help laughing. Of course, the boy can not invest in all the things he sees at the fair; he has to stop when his pocket money runs out. But there is lots of free fun, such as the chance to roam around and look on at everything, and he has quantities of handbills and brightly colored cards and pamphlets thrust upon him, all of which he faithfully stows away in his gradually bulging pockets and takes home to consider at leisure. For a number of days afterward he squeaks about on his journeyings with his whistles and jews-harps and other noise-makers purchased at the fair,with great persistency; but these things soon get broken, and the pamphlets and circulars he gathered get scattered, and the occasion may be said to have been brought to an end by his finding, two Sundays later, a lone peanut in his jacket pocket. It was in church time, and he was at great pains to crack it quietly, so that he could eat it at once. He succeeded, though he had to assume great innocence and a remarkably steadfast interest in the preacher when his mother glanced his way suspiciously as she heard the shucks crush.  Shooting with a sling Autumn is a time of harvest. The potato field has first attention. When the boy's father is otherwise busied, he has to go out alone and do digging and all, unless he can persuade his smaller brothers and sisters to bring along their little express wagon and assist. In such a case he spends about half his time showing them how, and offering inducements to keep them at work. Usually it is the men folks who dig, and the boy has to do most of the picking up. After he has handled about five bushels of the dirty things he has had enough of it; but he can not desert. It is one of the great virtues of farm life that the boy must learn to do disagreeable tasks, and to stick to them to the finish however irksome they are. It gives the right kind of boy a decided advantage in the battles of life that come later, whatever his field of industry. He has courage to undertake and persistence to carry out plans that boys of milder experience will never dare to cope with. Potato fields that have been neglected in the drive of other work in their ripening weeks, flourish often at digging time with many weedy jungle. This made digging slow, but the economical small farmer saw some gain in the fact, for he could feed the weeds to the pigs. After the midday digging, while the boy's father was carrying the bags of potatoes down cellar, the boy wheeled in a few loads of the weeds. The pigs were very glad to come wallowing up from the barnyard mire to the bars where the boy threw the weeds over. They grunted and crunched with great satisfaction. When the boy brought in the last load, he had a little conversation with the pigs, and he scratched the fattest one's back with a piece of board, until the stout porker lay down on its side and curled up the corners of its mouth and grunted as if in the seventh heaven of bliss.  A corner of the sheep yard A little later in the fall the onions have to be topped, the beets pulled, the carrots spaded out, and the corn cut. Work at the corn, in one shape or another, hangs on until snow flies. The men do most of the cutting and binding, though the boy often assists; but what he is sure to do is to drop the straw and to hand up the bundles when they are ready for stacking, and gather the scattered pumpkins and put them under the stacks to protect them from the frost. He likes to play that these stacks are Indian tents, and he will crowd himself in among their slanting stalks till he is out of sight. He picks out one or two good-sized green pumpkins that night from among those they have brought home to feed to the cows, and hollows them out and cuts awful faces on them for jack-o'-lanterns. He fixes with considerable trouble a place in the bottom for a candle, and gets the younger children to come out on the steps while he lights up. They are filled with delight and fright by the ghostly heads with their strangely glowing features and their grinning, saw-toothed mouths. The boy goes sailing around the yard with them, and puts them on fence-posts and carries them up a ladder, and cuts up all sorts of antics with them. Finally, the younger children are called in, and the boy gets lonesome and blows out his candles, and puts the jack-o'-lanterns away for another occasion. On days following there is much corn-husking in the fields, which the boy assists at, though the breaking off of the tough cobs is often no easy matter, and it makes his wrists and fingers ache. Toward sundown the farmer frequently brings home a load to husk in the evening, or for the morrow's work should the day chance to be rainy. In the autumn it is quite common to do an hour or two's work in the barn of an evening, though the boy does not fancy the arrangement much, and begs off when he can think of a good excuse.  Helping grandpa husk In October the apples have to be picked. The pickers go to the orchard armed with baskets, ropes, and ladders, and the wagon brings out a load of barrels and scatters them about among the trees. It looks dangerous the way the boy will worm about among the branches and pursue the apples out to the tips of the smallest limbs. He never falls, though he many times comes near it. The way he hangs on seems to confirm the truth of the theory that he was descended from monkey ancestors. But the boy is on the ground much of the time, emptying the baskets the men let down into the barrels and picking up the best of the windfalls, and gathering the rest of the apples on the ground into heaps for cider.  Out for a tramp It is a treat to take the cider apples to mill. There is always something going on there — always other teams and other boys, and great bins of waiting apples and creaking machinery, and an atmosphere full of cidery odors. The boy loses no time in hunting up a good straw and finding a newly filled barrel with the bung out. He establishes prompt connections with the cider by means of the straw, and fills himself up with sweetness. When he has enough, and has wiped his mouth with his sleeve, he remarks that he guesses he has lowered that cider some. When they brought their own cider home and propped up the barrels in the yard next the shop, the boy kept a bunch of straws conveniently stored, and as long as he called the cider sweet he frequently drew on the barrels' contents. When the cider grew hard he took to visiting the apple bins more frequently, and, if you noticed him closely, you would almost always see that he had bunches in his pockets that showed that he was well provided with these food stores.  A drink at the tub in the back yard The great day of the fall for the boy was that on which he and a lot of the other fellows went chestnutting. They had been planning it and talking it over for a week beforehand. The sun had not been long up when they started off across the frosty quiet of the pastures. Some had tin pails, some had bags, some had both. One boy had hopes so high that he carried three bags that would hold half a bushel each. Most of them had salt bags that would contain two or three quarts. Several carried clubs to knock off the chestnuts that still clung in the burs. They were all in eager chatter as they tramped and skipped and climbed the fences and rolled stones down the hillside and whirled their pails about their heads, and waited for the smallest boy, who was getting left behind, to catch up, and did all those other things that boys do when they are off that way. How they raced to be first when they neared the chestnut trees! There was a scattering, and a shouting over finds, and a rustling among the fallen leaves. The nuts were not so numerous that it took them long to clear the ground. Then they threw their clubs, but the limbs were too high for their strength to be effective, and they soon gave up and went on to find more trees. The chestnuts rattled on the bottoms of their tin pails, and the boys with bags twisted them up and exhibited to each other the knob of nuts within. As the sun rose higher the grass became wet with melted frost, and the wind began to blow in dashing little breezes that kept increasing in force till the whole wood was set to singing and fluttering. The boys enjoyed the briskness of the gale, and agreed, besides, that it would bring down the chestnuts. They wandered on over knolls and through hollows, sometimes in the brown pastures, sometimes in the ragged, autumn forest patches. They clubbed and climbed and picked, and bruised their shins, and got chestnut-bur prickles into their fingers, and they had some squabbles among themselves, and the smallest boy tumbled and got the nose-bleed and shed tears, and it took the whole company to comfort him. On the whole, though, they got on very well. At noon the biggest boy, who had a watch, told them it was twelve o'clock, and they stopped on the sunny side of a pine grove, where there was a brook that slipped down over some rocks near by, and ate their dinner. The wind was whistling and swaying high up among the pine-tops, and now and then a tiny whirlwind caught up the leaves beyond the brook and dashed them into a white-birch thicket. In the sheltered nook where the boys sat the wind barely touched them, and they ate, and drank from the brook, and lounged about afterward in great comfort. They followed the little stream down a rough ravine, when they again started and went through the same experiences as those of the morning. They saw two gray squirrels, they heard a hound baying on the mountain, and there was a gun fired off somewhere in the woods. They found a crow's nest, only it was so high in a tree that they could not get it, and they picked up many pretty stones by the side of the brook that they put in with their chestnuts. They got under one tree that was in sight of an orchard where a man was picking apples. The man hallooed to them to "get out of there!" and after a little hesitation — for the spot was a promising one — they straggled off into the woods again. While they traveled they did a good deal of odd eating. They made way with an occasional chestnut, and they found birch and mountain mint, and dug some sassafras root, which they ate after getting most of the dirt off. The biggest boy's name was Tom Cook, and he would eat almost anything. He would eat acorns, which the rest found too bitter, and he would chew pine and hemlock needles and sweet-fern leaves, and all such things. He got out his knife while they were crossing a pasture and cut out a plug of bark from a pine tree and scraped out the pitch and juice next the wood, and said it was sweet. The others tried it, and it was sweet, though they did not care much for it.  Over the pasture hills to the chestnut trees In the late afternoon the squad of boys came out on a precipice of rocks that overhung a pond. The wind had gone down and the sun was getting low, and it seemed best that they should start homeward. They were back among the scattered houses of the village just as the evening had begun to get dusky and frosty. The smallest boy had more than a pint of chestnuts, and the biggest boy had as many as three quarts, not counting stones and other rubbish. The day had been a great success, but they felt as if they had trudged a thousand miles, and were almost too tired to eat supper. However, when the boy began to tell his adventures, and set forth in glowing terms his triumphs and trials, and listed the wonderful things he had seen, his spirits revived, and in the evening he was able to superintend the boiling of a cup of the chestnuts he had gathered, and to do his share of the eating.  A mud turtle When the chestnut burs opened, autumn was at its height. Now it began to decline. Every breeze set loose relays of the gaudy leaves and sent them fluttering to the earth in a many-tinted shower, and the bare twigs and the increasing sharpness of the morning frosts warned the farm dwellers that winter was fast approaching. |