| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

PART

II.

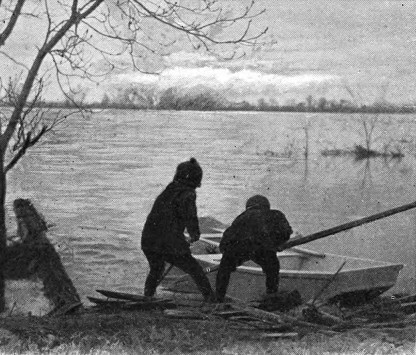

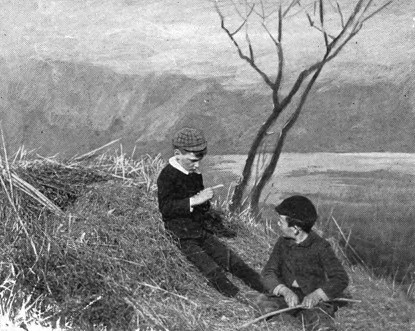

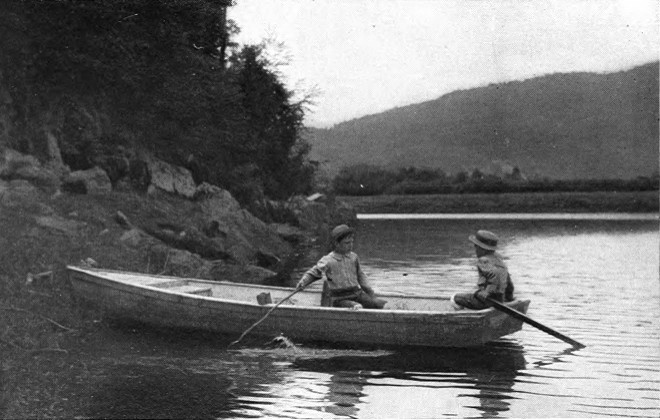

SPRING.  A new picture paper WITH the coming of March comes spring, according to the almanac, but in New England the snowstorms and wintry gales hold sway often to the edge of April. Yet you can generally look for some vigorous thaws before the end of the month. There are occasional days of such warmth and quiet that you can fairly hear the snow melt, and the air is full of the tinkle of running brooks. You catch the sound of a woodpecker tapping in the orchard, and the small boy tumbles into the house, jubilant over the fact that he has seen a bluebird flitting through the branches of the elm before the house. All the children make haste to run out into the yard to see the sight. Even the mother throws a shawl over her head and steps out on the piazza. "Yessir! there he is!" says Tommy, excitedly. "That's a bluebird, sure pop!" Puddles have gathered in the soggy snow along the roadside, and the little stream in the meadow has overflowed its banks. When the boy perceives this, he becomes immediately anxious to get into his rubber boots and go wading. His mother has a doubtful opinion of these wadings, but it is such a matter of life and death to the boy that she has not the heart to refuse him, and contents herself with admonitions not to stay out too long, not to wade in too deep, not to get his clothes wet, etc., etc. The boy begins with one of the small puddles, for he has these cautions in his mind, but the scope of his enterprise continually enlarges, and he presently finds himself trying to determine just how deep a place he can get into without letting the water in over his boot-tops. He does not desist from the experiment until he feels a cold trickle down one of his legs, from which he concludes that he got in just a little too far that time, and he makes a hasty retreat. But he has made his mind easy on the point as to how deep he can go, and now turns his attention to poking about with a stick he has picked up. He is quite charmed with the way he can make the water and slush spatter with it. When he gets tired with this, and the accumulating wet begins to penetrate his clothing here and there, he adjourns to the meadow and sets his stick sailing down the stream there. It fills his heart with delight to see the way it pitches and whirls, and he slumps along the brook borders and shouts at it as he keeps it company. Later he returns to the roadway and makes half a dozen dams or more to stop the tiny rills that are coursing down its furrows. He does this with such serious thoughtfulness and with such frequent, studious pauses as would well fit the actions of some of the world's great philosophers.  Catching flood-wood No doubt the boy is making discoveries and learning lessons; for the farm, with varied Nature always so close, is an excellent kindergarten, and the farm child is all the time improving its opportunities after some fashion. When our boy goes indoors his mother shows symptoms of alarm over his condition. He thinks he has kept pretty dry, but his mother wants to know what on earth he's been doing to get so wet. "Ain't been doin' nothin'," says Tommy. "Well, I should say so!" remarks his mother. "Here, you let me sit you in this chair to kind o' drean off, while I pull off them soppin' mittens." She has to wring the mittens out at the sink before she hangs them on the line back of the stove. Next she pulls off the boy's boots, and stands him up while she takes off his overcoat, and lastly pushes him, chair and all, up by the fire, where he can put his feet on the stove-hearth. Tommy did not see the necessity for all this fuss. He felt dry enough, and all right; yet, as long as his mother does not get disturbed to the chastising point, he finds a good deal of comfort in having her attend to him in this way. It was on one of these still, sunshiny March days that it occurred to the oldest boy of the household that it was about time for the sap to begin to run. He does not waste much time in making tracks for the shop, where he hunts up some old spouts and an auger. He will tap two or three of the trees near the house, anyway. There is no lack of helpers. All the smaller children are on hand to watch and advise him, and to fetch pans from the house and prop them up under the spouts. They watch eagerly for the appearance of the first drops, and when they sight them each tells the rest that "There they are!" and "It does run!" and they want their older brother to stop his boring at the next tree and come and look. But William feels that he is too old to show enthusiasm about such things, and he simply tells them that he guesses that he's "seen sap 'fore now." The children take turns applying their mouths to the end of spout number one to catch the first drops that trickle down it. In days following they are frequent visitors to these tapped trees, with the avowed purpose of seeing how the sap is running; but it is to be noticed that at the same time they seem always to find it convenient to take a drink from a pan. In the more hilly regions of New England most of the farms have a sugar orchard on them, and the tree-tapping that begins about the house is soon transferred to the woods. The boy goes along, too — indeed, what work is there about a farm that he does not have a hand in, either of his own will or because he has to? But the phase I wish now to speak of is that found on the farms that possess no maple orchard. The boy sees that the trees about the house are attended to, as a matter of course, and he guards the pans and warns off the neighbors' boys when he thinks they are making too free with the pans' contents. Each morning he goes out with a pail, gathers the sap, and sets it boiling in a kettle on the stove. In time comes the final triumph, when, some morning, the family leaves the molasses pot in the cupboard, and they have maple sirup on their griddle-cakes. It is not every boy whose enterprise stops with the tapping of the shade trees in front of the house. On many farms there is an occasional maple about the fields, and sometimes there are a few in a patch of near woodland. In such a case the boy gathers a lot of elder-stalks while it is still winter, cleans out the pith, and shapes them into spouts. At the first approach of mild weather he taps the scattered trees and distributes among them every receptacle the house affords that does not leak, or whose leaks can be soldered or beeswaxed, to catch the sap. After that, while the season lasts, he and his brother swing a heavy tin can on a staff between them and make periodical tours sap-collecting. These frequent tramps through mud and snow in all kinds of weather soon become monotonously wearisome, and the boys usually find one season of this kind of experience enough.  A hillside sheep pasture With the going of the snow comes a mud spell that lasts fully a month. It takes you forever to drive anywhere with a team. It is drag, drag, drag, and slop, slop, slop all the way. Even the home dooryard is little better than a bog, and the boy can never seem to step out anywhere without coming in loaded with mud — at least, so his mother says. She has continually to be warning him to keep out of the sitting-room, and at times seems to be thrown into as much consternation over some of his footprints that she finds on the kitchen floor as was Robinson Crusoe over the discovery of that lone footprint in the sand. Just as soon as she hears the boy's shuffle on the piazza and catches sight of him coming in at the kitchen door, she says, "There, Willy, don't you come in till you've wiped your feet." "I have," says Willy. "Why, just look at 'em!" his mother responds. "I should think you'd got about all the mud there was in the yard on 'em." "I never saw such sticky old stuff," says Willy. "Your broom's most wore out already." "Well," remarked his mother, "what are you gettin' into the mud for all over that way, every time you step out? Pa's laid down boards all around the yard to walk on. Why don't you go on them?" "They ain't laid where I want to go," replies Willy. "Anyway," is his mother's final remark, "I can't have my kitchen floor mussed up by you trackin' in every five minutes." But the really severe experiences in this line come when the barnyard is cleaned out. For several days the boy's shoes are "a sight," and his journeyings are accompanied with such an odor that his mother warns him off entirely from her domains. He is not allowed to walk in and get that piece of pie for his lunch, but has it handed out to him through the narrowly opened kitchen door. When mealtime comes he has to leave his shoes and overalls in the woodshed, and comes into the house in his stocking-feet. Even then his mother makes derogatory remarks, though he tells her he "can't smell anything." It is astonishing how quickly, after the snow goes, the green will clothe the fields, and how, with bursting buds and the first blossoms, all Nature seems teeming with life again. I think the sentiment of the boy is touched by this season more than by any other. The unfolding of all this new life is full of mysterious charm. It is a delight to tread the velvety turf, to find the first flowers, to catch the oft-repeated sweetness of a phoebe's song, or the more forceful trilling of a robin at sundown. It is at nightfall that spring appeals to the boy most strongly. He can still feel the heat of the sun when it lingers at the horizon, and in the gentle warmth of its rays enjoys a run about the yard, and claps at the little clouds of midges that are sporting in the air. As soon as the sun disappears there is a gathering of cool evening damps, and from the swampy hollows come many strange pipings and croakings. The boy wonders vaguely about all the creatures that make these noises, and imitates their voices from the home lawn. When the dusk begins to deepen into darkness he is glad to get into the light and warmth of the kitchen.  Spring chickens To tell the truth, our boy is rather afraid of the dark. Just what he fears is but dimly defined, though bears, thieves, and Indians are among the fearsome shades that people the night glooms. It does not take much of a noise, when he is out alone in the dark, to set his heart thumping, and his imagination pictures dreadful possibilities in the shapes and movements that greet his eyesight. This fear is not confined to out-of-doors. He has a notion that there may be a lurking savage in the pantry, or the cellar, or the dusky corners of the hallways, or, worst of all, under his bed. Those fears are most vivid after he has been reading some tale of desperate adventure or of mystery, dark doings and evil characters. Very good books and papers often have in them the elements that produce these scary effects. These are the sources of his timidity, for dime-novel trash, although not altogether absent, is not common in the country. The boy does not usually acquire much of his fear from the talk of his fellows, and his parents certainly do not foster such feelings. It is undoubtedly his reading, mainly. He rarely feels fear if he has company, or if he is where there is light, or after he gets into bed — that is, unless there are noises. What makes these noises you hear sometimes in the night? You certainly don't hear such noises in the daytime. The boy does not mind rats. He knows them. They can race through the walls, and grit their teeth on the plastering, and throw all those bricks and things, whatever they are, down inside there that they want to. But it's these creakings and crackings and softer noises, that you can't tell what they are, that are the trouble. The very best that you can do is to pull the covers up over your head and shiver into sleep again. But if the boy has frights, they are intermittent, for the most part, and soon forgotten.  Willow whistles With the thawing of the snow on the hills and the early rains comes, each spring, a time of flood on all the brooks and rivers that no one appreciates more than the boy who is so fortunate as to have a home on their banks. Water, in whatever shape, possesses a fascination for the boy, if we except that for washing purposes. It does not matter whether it is a dirty puddle or a sparkling brook or the spirting jet at the highway watering-trough — he wants to paddle and splash in every one. He even sees a touch of the beautiful and sublime in water in some of its effects. There is a charm to him in the placid pond that mirrors every object along its banks, or, on brisker days, in the choppy waves that break the surface and curl up on the muddy shore. He likes to follow the course of a brook, and takes pleasure in noting the clearness of its waters and in watching its crystal leaps. When spring changes the quiet streams into muddy torrents, and they become foaming and wild and unfamiliar, the boy finds the sight impressive and exhilarating. But it is on the larger rivers that the floods have most meaning. The water sets back in all the hollows, and broadens into wide lakes on the meadows, and covers portions of the main road. The boy cuts a notch in a stick and sets his mark at the water's edge, that he may keep posted as to how fast the river is rising. He gets out the spike pole and fishes out the flood-wood that floats within reach. If he is old enough to manage a boat, he rows out into the stream and hitches on to an occasional log or large stick that is sailing along on the swift current. For this purpose, if he is alone, he has an iron hook fastened at the back end of the boat that he pounds into the log. It is hard, jerky work towing a log to shore, and he does not always succeed in landing his capture. Sometimes the hook will keep pulling out; sometimes the thing he hitches onto is too bulky or clumsy, and, after a long, hard pull, panting and exhausted, he finds himself getting so far downstream that he reluctantly knocks out the hook, rows inshore, and creeps in the eddies along the bank back to his starting place. There is just one trouble about this catching flood-wood — it increases the woodpile materially, and makes a lot of work, sawing and chopping, that the boy has little fancy for. In the early spring there is sometimes a long-continued spell of dry weather. In the woods the trees are still bare, and the sunlight has free access to the leaf-carpeted earth. At such a time, if a fire gets started among the shriveled and tinderlike leaves it is no easy task to put it out. Whole neighborhoods turn out to fight it, and several days and nights may pass before it is under control. The boy is among the first on the spot with his hoe, and immediately begins a vigorous scratching to clear a path in the leaves that the fire will not burn across. The company scatters, and sometimes the boy finds himself alone. Close in front, extending away in both directions, is the ragged fire line leaping and crackling. The woods are still, the sun shines bright, and there is a sense of mystery and danger in the presence of those sullen, devouring flames. Now comes a puff of wind that causes the fire to make a sudden dash forward and shrouds the boy with smoke. He runs back to a point of safety and listens to the far-off shouts of the men. The fire is across the path he hoed, and he picks a piece of birch to eat while he clambers up the hill to find company.  The opening of the fishing season When night comes the boy wanders off home, to do his work and eat supper. If he is allowed, he is out again with his hoe in the evening. The scene is full of a wild charm. From the somberness of the unburned tracts you look into the hot, wavering line of dazzling flames and on into regions where linger many sparkling embers which the fire has not yet burned out, and now and then there is a pile of wood that is a great mass of glowing coals, and again the high stump of some dead tree that burns like a torch in the blackness. The boy thinks the men do more talking and advising than work. He does not accomplish much himself. The men keep together, and he hangs about the dark, half-lighted groups, listens to what is said, and with the others does some desultory scratching to keep the fire from gaining new ground at the point they are guarding. By-and-by there comes a man hallooing his way through the woods to them, who has brought a milk-can full of coffee. Every man and boy takes a drink, and they all crack jokes and exchange opinions with the bearer till he starts off to find the next group. Some of the men stay on guard all night, but the boy and his father, about ten o'clock, leave the crackle and darting of the flames behind them, and take a gloomy wood-road that leads toward home. There has been nothing very alarming in the day's adventures, but the boy never forgets the experience. Fire is fascinating to the boy in any form. He burned his fingers at the stove damper when he was a baby. He likes to look at the glow of a lamp; and a candle, with its soft flicker and halo, is especially pleasing. Then those new matches his folks have got, that go off with a snap and burst at once into a sudden blaze — he has never seen anything like them. They remind him of the delights of Fourth of July.  Leap-frog in the front yard A chief event of the spring is a bonfire in the garden. There is an accumulation of dead vines and old pea-brush and apple-tree trimmings that often makes a large heap. The fire is enjoyable at whatever time it comes, but it is at its best if they touch it off in the evening. The whole family comes out to see it then, and Frank fixes up a seat for his mother and the baby out of a board and some blocks, and invites some of the neighbors' boys to be on hand. He puts an armful of leaves under a corner of the pile and sets it going with some of those parlor matches. The neighbors' boys stand around and tell him how, and even offer to do it themselves. When the blaze fairly starts and begins to trickle up through the twigs above it the smaller children jump for joy and clap their hands, and run to get handfuls of leaves and scattered rubbish to throw on. Frank pokes the pile this way and that with his pitchfork, and the neighbors' boys light the ends of long sticks and wave them about in the air. Even the baby coos with delight. The father has a rake and does most of the work that is really necessary, while the boys furnish all the action and noise needful to make the occasion a success. When the blaze is at its highest and the heat penetrates far back, the company becomes quiet, and they stand about exchanging occasional words and simply watching the flames lick up the brush and flash upward and disappear amid the smoke and sparks that rise high toward the dark deeps of the sky. The frolic is resumed when the pile of brush begins to fall inward, and presently mother says she and the baby and the smallest children must go in. The latter protest, but they have to go, and not long after the embers of the fire are all raked together, and Frank and the neighbors' boys fool around a little longer, and get about a half-dozen final warming-ups and then tramp off homeward in whistling happiness. On the day following the garden is plowed and harrowed. Then the boy has to help scratch it over and even it off with a rake, and is kept on the jump all the time getting out seeds and planters and tools, that never seem to be in the right place at the right time. Meanwhile he induces his father to let him have a corner of the garden for his own, and gets his advice as to what he had best put in it to make his fortune. He scratches over the plot about twice as fine as the rest of the garden, and won't let any of the old hens that are hanging around looking for worms come near it. He has concluded that peas are the things to bring in money, but he is tempted to try three or four hills of potatoes between the rows after he has the peas in. He has saved space for a hill of watermelons, and, just to fill up the blanks, which seem rather large with nothing yet up, he puts in as a matter of experiment a number of other seeds here and there of one sort and another. He puts these in from time to time along when it comes handy and the thought occurs to him. He was somewhat astonished at the way things came up. Indeed, he thought they would never get done coming up, and they were pretty well mixed in their arrangement. He got so discouraged over the things that kept sprouting in one corner that he hoed the whole thing up on that spot and transplanted a few cabbages on it. He used to get his mother to come out and look at his garden-patch, and he enjoyed telling her his plans; but he left that off for a while when the things became so erratic, and waited till he could thin them out and bring their proceedings within his comprehension.  A blossom for the baby It is in spring, more than any other season, that the boy's ideas bud with new enterprises. He forgets most of them by the time he has them fairly started, and none of them are apt to have any pecuniary value. But that never damps his enthusiasm in rushing into new ones. The hunting fever is apt to take him pretty soon after the snow goes, and he makes a bow and whittles out some arrows and turns Indian. He may even visit the resorts of the hens and collect enough feathers to make a circlet to wear round his head. Then he goes off and hunts bears and things, and scalps the neighbors' boys. Sometimes, instead of being an Indian, he gets his father to saw out a wooden gun and turns pioneer. Then savages and wild animals both have to catch it. He will skulk around in the most approved fashion and say "Bang!" for his gun every time he fires, and he will like enough kill half a hundred Indians and a dozen grizzly bears in one forenoon. He is fearless as you please — until night comes. Not all the boy's hunting is so mild as to stop at the killing off of bears and Indians. Sometimes he shoots his arrows at real, live things, or he has a rubber sling, or he practices throwing stones; and does not resist the temptation to make the birds and squirrels, and possibly the cats and the chickens, his marks. It is true he rarely hits any of them; and the sensitive boy, if he seriously hurts one of the creatures fired at, has a twinge of remorse. But there are those who will only glory in the straightness of their aim. There is something of the savage still in their nature, and they feel a sense of prowess and power in bringing down that which, in spite of its life and movement, did not escape them. It is to them a much grander and more enjoyable thing than to hit a lifeless and unmoving mark.  Playing "Indian" The boys — at any rate many of them — are at times, in a thoughtless way, downright cruel. See how they will bang about the old horse upon occasion! They have no compunctions about drowning a cat or wringing the neck of a chicken, and will run half a mile to be present at a hog-killing. They have barely a grain of sympathy for the worm they impale on their fish-hooks; they kill the grasshopper who will not give them "molasses"; they crush the butterfly's wings in catching it with their straw hats; and they pull off insects' limbs to see them wriggle, or to find out how the insect will get along without them. I will not extend the horrible list, and I am not sure but that most boys would be guiltless of the majority of these charges. However, they are much too apt to play the part of destroyers. This spirit is shown in the way the boy will whip off the heads of flowers along his path, if he has a stick in his hand, and the manner in which he gathers them when gathering happens to be his purpose. He never thinks of their life or of their beauty where they stand, or of the future. He picks them all, snaps off the heads, pulls them up by the roots — any way to get the whole thing in the shortest possible time. If the boy was as thorough as he is ruthless, you could never find more flowers of the same sort on that spot. This does not argue a total disregard for the flowers, but it is a pity to love a thing to destruction.  On the way to pasture The first token of spring in the flower line that the boy brings into the house is probably a sprig of pussy-willow. The fuzzy catkins are to his mind very odd and interesting and pretty. The ground is still snow-covered, and they have started with the first real thaw. Before the pastures get their first green the boy goes off to find the new arbutus buds, that smell sweetest of all the flowers he knows, unless it may be honeysuckle, that comes later. Already by the brook are the queer skunk-cabbage blossoms, and the boy sometimes pulls one to pieces, and even sniffs the odor, just to learn how bad it really is. He may find a stout, short-stemmed dandelion thus early open in some warm, grassy hollow, and a few days later the anemone's dainty cups are out in full and trembling on their slender stems with every breath of air. In pasture bogs and along the brooks are violets — mostly blue; but in places there are yellow and white ones, ready to delight their finder. The higher and drier slopes of the pastures are in spots sometimes almost blue with the coarse bird-foot violets, while lower down the ground is as white with the multitudes of innocents as if there had been a light snowfall. Along the roadways and fences the wild-cherry trees are clouded full of white petals, and in the woods are great dashes of white where the dogwoods have unfurled their blossoms. By the end of May the meadows are like a night sky full of stars, so thick are the dandelions, and on the rocks of the hillside the columbines sway, full of their oddly shaped, pendulous bells. In some damp woodpath the boy is filled with rejoicing by the finding of one of the rare lady's-slippers where he has been gathering wake-robin. The only other spring flower I will mention as of special interest to the boy is the Jack-in-the-pulpit, and that hardly seems a flower to him, it is so queer.  Discussing the colt Spring has three days with an individuality that makes them stand out among the rest. The 1st of April is April Fool's Day. The only idea the boy has about it is that the more things he can make the rest of the world think on that day are not so, the better. It has to be acknowledged that most of the tricks are not very clever or commendable, and the boy himself feels that he is sometimes getting uncomfortably close to lying. The common form of fooling is to get a person to look at something that is not in sight.  A little housekeeper "See that crow out there!" says the boy to his father. "Where?" asks his father, when he looks out. "April fool!" shouts the boy, and he is pleased with the slick way he fooled his pa, for about half an hour, when he discovers that he has been walking around for he doesn't know how long with a slip of paper on his back that his sister pinned there; and what he reads on it when he gets it off is "April fool!" He does not feel so happy then, but he saves the paper to pin on some one else. All day his brain is full of schemes to get people looking at the imaginary objects he calls their attention to, and at the same time he is full of suspicions himself, and you have to be very sharp and sudden to fool him. When night comes he rejoices in the fact that he has got one or two "fools" off on every member of the family, and there is no knowing what a nuisance he has made of himself among the rest of his friends. It gives him a grand good appetite, and he feels inclined to be quite conversational. His remarks, however, assume a milder tenor when he bites into a portly doughnut and finds it made of cotton. He is afraid his mother is trying to fool him. He wouldn't have thought it of her!  Some fun in a boat Soon after this day comes Fast Day. School "lets out," and there's meeting at the church, but most folks do not pay much attention to that, and, it being a holiday, they eat rather more than on other days, if anything, and they joke about its being "fast" in the sense that it is not slow. Our boy does what work he has to do, and then asks the privilege of going off to see some other boy and have some fun. However, that is a thing that happens on all sorts of days. He is always ready with that request when he has leisure, and makes it oftentimes, too, when he has no leisure in any one's opinion but his own. The 30th of May is Decoration Day, and a company of soldiers will come with a band and flags, and will decorate the graves of the soldiers in the little cemetery, and there will be singing and other exercises, and everybody will be there. The boy has his bouquet, and he is on the spot promptly and chatting with some of his companions. It may be the quiet of the early morning that is the appointed time. There are lines of teams hitched along the roadside, and two or three score of waiting people have gathered near the entrance. The occasion has something of the solemnity of a funeral, and even the boys lower their voices as they talk. The sound of a drum and fife is heard around the turn of the road; the soldiers, under their drooping flag, approach and file into the cemetery. A song, an address, and a prayer follow — all very impressive to the boy, out there under the skies with the wide, blossoming landscape about. Finally, he lays his flowers with the others on the graves, the soldiers form in line, the fife pipes once more, the drum beats, and off they go down the road. Then the people begin a more cheerful visiting, and there is a cramping of wheels as the teams turn to go homeward. The boy, with his friends, pokes about among some of the old stones, and then lingers along in the rear of the scattered groups that are taking the road that leads to the village. |