|

II. THE METROPOLITAN REGION

The

thirty-six cities and towns comprising with modern Boston the

Metropolitan District (see Plate V), all lying in the “Boston

Basin,” or touched by a circle with a radius of ten

miles from the State House, are:

CITIES

— Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Lynn, Malden, Medford, Melrose,

Newton, Quincy, Somerville, Waltham, and Woburn.

Towns

— Arlington, Belmont, Braintree, Brookline, Canton, Dedham, Hull,

Hyde Park, Milton, Nahant, Lexington, Needham, Reading, Revere,

Saugus, Stoneham, Swampscott, Wakefield, Watertown, Wellesley,

Weston, Weymouth, Winchester, and Winthrop.

All

of these places, with the exception of Hull and Nahant, are within

the suburban districts of the railroads terminating in Boston, with

frequent train service, and are embraced in the electric-railway

system.

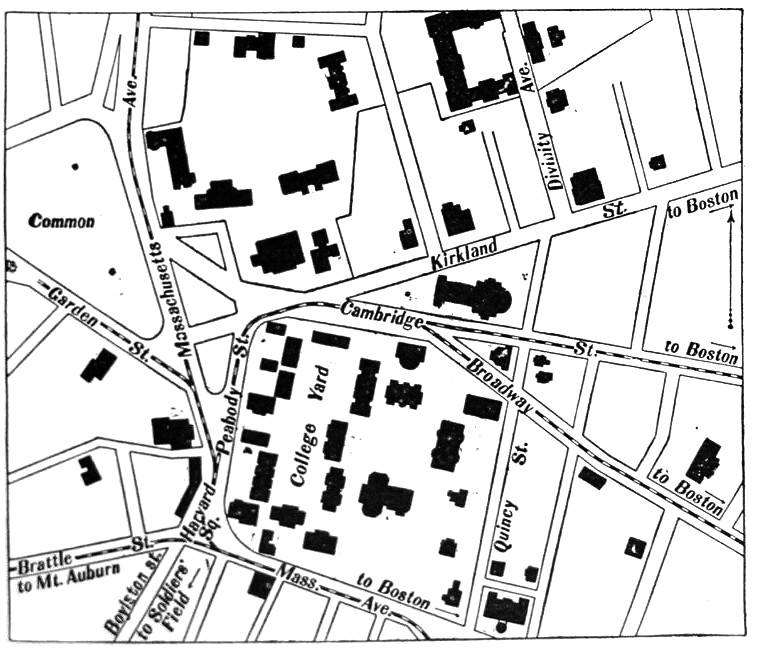

CAMBRIDGE

AND HARVARD

Harvard

Square is our destination, and it is barely a half hour’s ride

by electric car taken in the Subway at Park Street station, or at

Copley Square (Boylston Street), or further out on Massachusetts

Avenue; or by an electric car taken at Bowdoin Square. Let us agree

to go by the latter route, purposing to return by the former, and not

forgetting, ere we board the car in Bowdoin Square, to glance at the

venerable Revere House, and especially at the little iron-railed

balcony from which Daniel Webster delivered many a famous speech. We

soon reach Charles Street, with the County Jail frowning on the

right, and cross Charles River by the new and massive Cambridge

Bridge, completed in 1907.

Athenaeum Press

First Street, Near

Cambridge Bridge

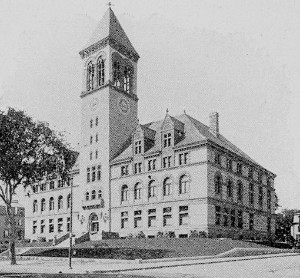

City Hall |

The

river crossed, we find ourselves in busy Cambridgeport so

called, amid factories and workshops, notably the great Athenæum

Press of Ginn & Company, near the river. A mile or so beyond

we pass Cherry Street; and on Cherry Street (at the corner of Eaton

Street) still stands the house in which Margaret Fuller was born.

A little farther on at the left is Magazine Street, where, at the

corner of Auburn Street Washington Allston once lived. Near by

on the right one observes a fine building of reddish granite with

brownstone trimmings and a clock tower. This is City Hall, the

gift of Frederick H. Rindge. The architects were Longfellow, Alden

&

Harlow. A short distance back of the City Hall may be seen a tablet

which marks the spot where General Israel Putnam had his

headquarters during the Siege of Boston. Other city institutions

may be seen by leaving the car at Trowbridge Street, at the end of

which will be found the Public Library (by Ware and Van Brunt,

1889) and the Manual Training School (by Rotch and Tilden). These

buildings also were the gift of Mr. Rindge. Close by are the Latin

School and the English High School.

|

|

Let

us suppose, however, that, with our minds fixed on the Harvard

University, we remain in the car until, rounding a corner,

we come upon a large Baptist church of slatestone. This has no

connection with the university, but it stands in strange contiguity

with Beck Hall, one of the most costly and luxurious of

Harvard dormitories, — not the property of the college. Alighting

here, we find ourselves at once on sacred ground. In front of us, and

to the left, is the “Yard.” To the right and separated

from the yard by Quincy Street is the new Harvard Union,

erected 1901, of which Henry L. Higginson and the late Henry Warren

were the chief donors. McKim, Mead & White were the architects.

It contains offices for the college papers, billiard rooms, a

restaurant, a good library, and a large assembly room. It is a sort

of home or meeting ground for graduates and undergraduates. Just

beyond is the Colonial Club, where may be found the

quintessence of Cambridge, the literary and academic élite.

These buildings are on the right of Quincy Street. Upon the opposite

side of the street, the first house, on the corner and within the

Yard, was formerly the Harvard Observatory. Afterward it

was the home of President Felton, and later of the venerated

Professor A. P. Peabody. The boundary wall of the yard in front of

this building, built in 1901, was given by the class of 1880.

The brick house next above is the president’s house; that next

beyond was long occupied by Professor Shaler. Next stands the newly

erected Emerson Hall in memory of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

|

|

Harvard Main Gate |

Let

us now retrace our steps and, turning the corner by the sometime

observatory, we come first to a gate given by Mrs. Wirt Dexter to

commemorate her son, Samuel Dexter, a member of the class of 1890,

who died in 1894. Next is the gate erected by the class of 1877, and

entering here we find ourselves in front of the Library, or

Gore Hall. The original building was the gift of

Christopher

Gore, a leading lawyer and governor of Massachusetts. Enlargements of

modern date have increased its usefulness, if not its beauty. The

library contains 400,200 bound volumes, and this number is swelled by

outlying collections in various departments of the university to

607,100, — to say nothing of pamphlets. For students who feel

unequal to mastering the library as a whole, a small lot of 22,500

volumes is provided on the easily accessible shelves of the reading

room. Among the valuable private collections that have been

contributed to the library are Parkman’s books, George Ticknor’s

collection of Dante literature, and Carlyle’s collection of books

relating to Cromwell and Frederick the Great. Emerging from the

library and skirting the yard to the right, we come first to Sever

Hall, a recitation building, simple, substantial, and dignified,

the work of the late H. H. Richardson. It was built in 1880 from a

fund given by Mrs. Anne E. P. Sever. To the left is the college

chapel, called Appleton Chapel, a building of light stone

erected in 1858, the gift of Samuel Appleton. Beyond it and facing on

Cambridge Street is a neat building of stone, almost white, brought

from Indiana. This is the William Hayes Fogg Art Museum, erected

in 1895, and given by Mrs. Elizabeth Fogg. It contains a large

collection of casts, statues, engravings, coins, etc., but leaves

something to be desired in point of beauty. Turning sharply to the

left and continuing to skirt the yard, we find at the bend in the

road the Phillips Brooks House, designed by A. W. Longfellow.

It is the center of the religious life of the university. In this

vicinity are two gates, one given by the class of 1876 and one by the

class of 1886.

|

Leaving

this house behind us and turning our steps toward the center of the

Yard, we come first to Holworthy, which was erected in 1812 from

money obtained by a lottery. Back of Holworthy, by the way, is

a gate given by George von L. Meyer, our Secretary of the Navy.

Holworthy from its slightly elevated site at the head of the yard,

occupies a commanding position, and has always been a favorite build

ing. It was the first dormitory that made any pretense to luxury, for

it is arranged in suites of three rooms for “chums,” — a study

in front and two bedrooms in the rear of the building. Class-Day

spreads and Commencement punches always found in Holworthy their

fittest home. In front of Holworthy the Glee Club sings, and noted

men gather in groups. Standing here we obtain the best view of the

beautiful Yard, with its great elms, its shadows, its splashes of

sunshine on the turf; or, of a Class-Day night, its festoons of

Japanese lanterns swaying from tree to tree. Who can number the

romances that have been transacted or begun in the deeply recessed

window seats, in the somber, academic, almost monastic shades of

Holworthy Hall! Time presses, however, and we must glance at the

other buildings in the Quadrangle.

|

Turning

to the right or westerly side of the Yard, we come first to

Stoughton, a dormitory built in 1805. In its rear,

or nearly

so, is Holden Chapel, the gift (1744) of Madam Holden of London, and

once the college chapel. It is now used for society meetings. Just

south of Holden Chapel is a gate given by the class of 1873, and

north of that a gate and sundial erected by the class of 1870. Next

comes Hollis Hall, also a dormitory, which dates back to 1763

and was the gift of Thomas Hollis of London. Three generations of

that family were benefactors of the college. This building was used

as barracks by the American soldiers in the Revolution at the time

when the college was temporarily removed to Concord. Next to Hollis

is Harvard Hall, a building which replaced an earlier Harvard

Hall burned in 1764. The present building was also used as barracks

in the Revolutionary War. It now holds some special libraries.

There is a cupola on Harvard Hall containing a bell which rings for

prayers and recitations. The space between the corners of the

two buildings, Harvard and Hollis, is only five or six feet, and

there is a tradition that once a student, trying to steal the tongue

of the bell, heard the janitor mounting the cupola, and running clown

the steep roof of Harvard, jumped across

the gap and landed safely on the roof of Hollis, whence he escaped.

|

Harvard Gate, Class of

1877 |

Next

in order comes Massachusetts, but between Massachusetts Hall and

Harvard Hall is the principal entrance from the street to the college

yard, through the beautiful Johnston gateway, designed by

Charles F. McKim. This is inscribed with the orders of the General

Court relating to the establishment of the college in 1636-1639 and

this extract:

After

God had carried vs safe to New England

and

wee had bvilded ovr hovses

provided

necessaries for ovr liveli hood

reard

convenient places for Gods worship

and

setled the civill government

one

of the next things we longed for

and

looked after was to advance learning

and

perpetvate it to posterity

dreading

to leave an illiterate ministery

to

the churches when our present ministers

shall

die in the dvst

New

Englands First Fruits.

Massachusetts

Hall, the oldest of the college buildings, was a gift to the

college by the Province in 1720. This hall also was occupied by

troops during the Revolution. Afterward it became a dormitory again,

later a lecture room, and it is now used for meetings and public

purposes. Beyond Massachusetts, in our tour of the Quadrangle, comes

Matthews Hall, a dormitory erected in 1872 through the

generosity of Nathan Matthews of Boston. This hall is said to stand

on the site of the old Indian College, which was built in 1654 and in

which several Indian youths struggled with the classics. One of them,

Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, took a degree and died. Just beyond Matthews

Hall, and facing on the square, is Dane Hall. This was

formerly the Law School, but is now occupied by the Bursar’s

office, lecture rooms, and a psychological laboratory. We come

next to Grays Hall, a modern dormitory which faces Holworthy

Hall, at the south end of the yard. It was the gift (1863) of Francis

C. Gray of Boston, and its site is probably that of the first college

building. Back of Grays Hall, and close to the street, is an ancient

wooden building, yet of dignified aspect, called Wadsworth House.

This house was built in 1726, jointly by the Province and by the

college, as a residence for the presidents of the institution. It was

Washington’s headquarters until, as we shall presently see, he

removed to the Longfellow house on Brattle Street. The speaker of the

Massachusetts House of Representatives, 1900-1903, James J. Myers,

who after his graduation at Harvard became a tutor and proctor, took

up his residence in Wadsworth House at that time, and, with rare

fidelity, has remained there ever since. Returning now to the

Quadrangle, the substantial granite building standing a little back

and near the street is Boylston Hall, built in 1857 from money

bequeathed by Ward Nicholas Boylston, whose picture, in flowered,

silk dressing gown and cap, lights up Memorial Hall. Boylston Hall is

devoted to chemistry. Next in order, and facing Matthews Hall, is

Weld Hall, a dormitory given to the college in 1872 by

William

F. Weld. Beyond that is a simple, graceful, and dignified building of

white granite, built in 1815 from a design by Bulfinch. It is called

University Hall, and for many years was the main

recitation

building. It is now used as an office building. University Hall and

Sever Hall might perhaps be described as the two buildings in the

yard which are beautiful in themselves, apart from any association.

Beyond University, standing at right angles with Holworthy, is Thayer

Hall, a dormitory given to the college in 1870 by Nathaniel

Thayer.

Passing

out of the Quadrangle and continuing to Cambridge Street, which

bounds the yard on the north, we have within view many buildings,

mostly of recent construction, belonging to the university. Opposite

the Phillips Brooks House, on the other side of the street, is

the Hemenway Gymnasium, given by Augustus Hemenway in 1878. To

the right is the Lawrence Scientific School building, given by

Abbott Lawrence in 1847, and reënforced in 1884 by a building in

Holmes’s Field just beyond, erected by T. Jefferson Coolidge of

Boston. In this last building the visitor may behold an electric

machine given to the college by Benjamin Franklin, and a telescope

used by Professor John Winthrop. Immediately in front of us is a

triangular-shaped piece of ground called the Delta, formerly

the college playground, until Memorial Hall, designed by Ware and Van

Brunt, was built there in the seventies. The statue in the Delta is

an ideal statue of John Harvard, whose bequest of his library

to the college in 1636 was really its start ing point. It is the work

of Daniel C. French, and the gift of Samuel J. Bridge. The exterior

of Memorial Hall may perhaps strike the visitor as lacking

unity and simplicity, but the interior will not disappoint him.

Memorial Hall proper, where are inscribed the names of those Harvard

graduates who died in the Civil War, is noble and impressive; and the

great dining hall, which occupies the whole western end of the

building, with room for over a thousand students, which is paneled

with oak, beautified by memorial stained-glass windows, and filled

with pictures and busts, all of which have an historic and some of

which have an artistic interest, is probably unique in this country.

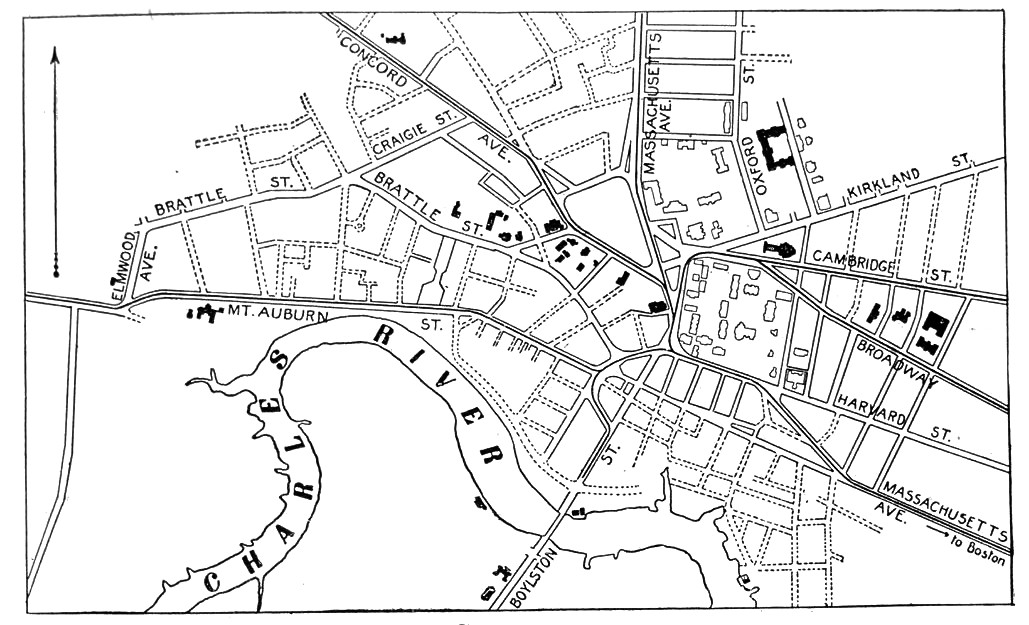

Cambridge

If,

before entering Memorial Hall (and Sanders Theatre), we turn to the

right on leaving the college yard, we shall come first to Robinson

Hall, at the corner of Quincy Street and Broadway, the

architectural building, containing many casts and engravings. On the

opposite side of Broadway, in the “Little Delta,”

is the old gymnasium, built in 1858, now occupied by the Germanic

Museum.

Of

the many other buildings belonging to the university in this

neighborhood only a few can be mentioned. Randall Hall, at the

corner of Divinity Avenue, with a dining room that seats five

hundred, is a good piece of architecture, constructed by Wheelwright

& Haven. Beyond are the Semitic Museum; Divinity Hall, an

unsectarian theological school; the University Museum,

comprising the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, the

Botanical Museum, the Mineralogical Museum, the

Geological Museum, and the Peabody Museum, founded

in

1866 by George Peabody, the American banker of London. All of these

are open to visitors, and all contain something to interest even the

unscientific person.

Returning

to the vicinity of the yard, mention should be made of the Law School

building, near the Hemenway Gymnasium, as this harbors one of the

strongest departments of the university. The Harvard Law School

has not only a national but an international reputation, and it has

been described by an English jurist as superior to any other school

of the kind in the world. The building was designed by H. H.

Richardson, the architect of Seaver Hall, to which, however, it is

scarcely equal. The library contains forty-four thousand volumes.

Near this hall once stood the yellow gambrel-roofed house in which

Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes was born. It was removed about

twenty years ago. The statue of Charles Sumner, by Miss Anne Whitney,

is in the triangular plot of ground near by.

|

Leaving

the university buildings we cross the Cambridge Common to the west of

the yard, formerly, by the way, a place of execution, and once the

scene of an open-air sermon by Whitefield. Here is a bronze statue of

John Bridge, the Puritan, in the garb of his time, an excellent piece

of sculpture by Thomas R. Gould and his son, Marshall S. Gould. In

the roadway, just west of the

Common,

stands the timeworn Washington Elm, to which is affixed a

tablet stating the historic fact that under this tree Washington

first took command of the American army. Opposite the Washington Elm

is the group of buildings belong ing to Radcliffe College, the

girls’ college, a recognized and highly successful part of the

university. These buildings are on the corner of Garden and Mason

streets.

|

Washington Elm |

Longfellow House |

This

venture of giving women instruction in the same studies that were

pursued at Harvard was begun in a small way in 1879. It was not a

part of Harvard, but, as a humorous student remarked, it was a

Harvard Annex. The name came into common use. The professors and

tutors as a rule were strongly in favor of the scheme, some even

offering to teach for nothing rather than have it fail. The Annex was

a success. The Fay house on Garden Street was bought. Lady Anne

Moulson in 1643 had given £100 as a scholarship to Harvard, the

first one. Her maiden name was Radcliffe, and as the Annex grew it

was incorporated as Radcliffe College, and now has several fine

buildings, a large number of students, and its diplomas bear the seal

of the older institution and the signature of its president. In the

Fay house, by the way, in 1836, the words of “Fair Harvard” were

written by the Rev. Samuel Gilman of Charleston, S.C.

|

|

Returning

toward the college we pass Christ Church, which was built in

1760 by Peter Harrison, who designed King’s Chapel in Boston.

Washington worshiped here. Adjoining the church is an old burying

ground which dates from 1636, the year of the founding of the

college. Near the fence will be observed a milestone bearing this

inscription: “Boston, 8 miles. 1734.” This was one of many mile

stones set up by Governor Dudley; and what is now a legend was once

true, for, before the bridges were constructed over the Charles River

between Boston and Cambridge, the highway connecting the two places

ran through Boston Neck and what is now Brighton, and was no less

than eight miles long.

|

Lowell House |

Some

outlying spots might well be visited if time allowed, especially the

great Stadium, erected in 1903, and Soldiers Field, the

present extensive playground of the university, a gift of Major Henry

L. Higginson. These are across the river, and near by are the

University and Weld boathouses. Brattle Street,

the

“Tory Row” of Provincial days, is easily reached by electric car

from Harvard Square, and is full of inter est. Here are the stone

buildings of the Episcopal Theological School, and just above

them the Longfellow house, one of the finest of colonial

mansions. It was built about the year 1759 by Colonel John Vassall, a

refugee of the Revolution. Washington took up his headquarters here

when he removed from Wadsworth House, and here Madam Washington

joined him. Afterward the estate passed into the hands of various

owners: was used as a lodging house by Harvard professors when the

widow Craigie owned it; was occupied by such distinguished persons as

Jared Sparks, Edward Everett, and Worcester, the dictionary maker;

and finally became the home of the poet Longfellow. It is now

occupied by a daughter, Miss Alice Longfellow, and next to it is the

home of another daughter who married a public-spirited citizen,

Richard H. Dana, son of the distinguished lawyer who wrote “Two

Years Before the Mast,” and grandson of the poet of the same name.

About ten minutes’ walk on Brattle Street beyond the Longfellow

house brings us to the corner of Elmwood Avenue, which leads

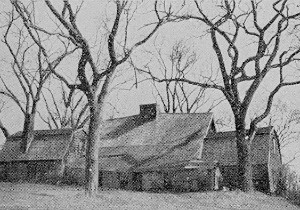

past the familiar Lowell house, where James Russell Lowell was

born, and which was his lifelong home. The seclusion of the house,

which Lowell so much enjoyed, is now impaired by the parkway which

skirts the Lowell grove. Mt. Auburn Street itself has been

modernized by a succession of public hospitals and the like.

Back of these hospitals, on the river, the

curious visitor may behold the site where Leif Ericson built his

house in the year 1001, or thereabout, — according to the

identification of Professor Eben N. Horsford, whose other memorials

of supposed Norsemen we shall encounter later. Close at hand is Mount

Auburn, celebrated for its natural beauty, as well as for the

distinguished dead who lie buried here. In the vestibule

of

the brownstone chapel at the left of the entrance to the cemetery are

the much-admired statues of John Winthrop (by Greenough), John Adams

(by Randall Rogers), James Otis (by Thomas Crawford), and Joseph

Story (by his son). Turning to the left we seek Fountain Avenue and

the graves of the Rev. Charles Lowell, of his son, James Russell

Lowell, and of the latter’s three nephews, all of whom were killed

in the Civil War. “Some choice New England stock in that little

plot of ground.” On the ridge back of this lot is the monument of

Longfellow, and near by (on Lime Avenue) the grave of Holmes. If,

instead of turning to the left from the entrance, we ascend the hill

to the right, passing the statue of Bow, ditch, the mathematician, we

shall come to the old Gothic chapel now used as a crematory. Facing

this stands the famous Sphinx, the work of Martin Milmore. Among

other monuments in various parts of the cemetery are those of William

Ellery Channing (Green-Briar Path), Hosea Ballou (Central Avenue),

Charles Sumner (Arethusa Path), Edward Everett (Magnolia Avenue),

Charlotte Cushman (Palm Avenue), Edwin Booth (Anemone Path), Louis

Agassiz (Bellwort Path), Anson Burlingame (Spruce Avenue), Samuel G.

Howe (near Spruce Avenue), and Phillips Brooks (Mimosa Path). In the

Fuller lot (Pyrola Path) is a monument to Margaret Fuller Ossoli.

From

the cemetery a Huron Avenue car will take us to the Astronomical

Observatory, and by walking through the observatory grounds we

can reach the Harvard Botanic Garden, laid out in 1807. This

garden, open to the public, is full of interesting features, such as

a bed of Shakespearean flowers, another of flowers mentioned by

Virgil, and still another of such quaint plants as grew in an

old-time New England garden.

The

sight-seeing resources of Cambridge are not yet exhausted, but the

sight-seer may be; and so from the Botanic Garden we will take an

electric car for Boston, “stopping off,” however, at Harvard

Square. Across Massachusetts Avenue, at the corner of Dunster

Street, we may observe the site, marked by a tablet, of the house

of Stephen Daye, first printer in British America, 1638-1648.

Here were printed the “Bay Psalm-Book” and Eliot’s Indian

Bible. Farther down Dunster Street, at the corner of Mt. Auburn

Street, is marked the site of the first meeting house in

Cambridge, set up in 1632; and still farther down, at the corner

of South Street, is a tablet where once stood the house of Thomas

Dudley, founder of Cambridge, who lived here in 1630.

From

the south side of Massachusetts Avenue leads off Bow Street, once the

great highway through these parts; and here may still be seen the

colonial mansion occupied in prerevolutionary days by Colonel David

Phips. In the same street the regicides Whalley and Gaffe were

in hiding (1660) until the king, learning of their presence, ordered

their arrest; they fled to New Haven. Just above Bow Street is

Plympton Street, where, shut in by modern brick

dormitories,

is a fine wooden colonial mansion, constructed about 1761 by the Rev.

East Apthorp, rector of Christ Church. Mr. Apthorp, it was supposed,

aspired to be a bishop, and consequently his house was called in

derision the “Bishop’s Palace.” Burgoyne was lodged here

after his surrender at Saratoga.

Taking

an electric car again, we return to Boston via the Harvard Ridge. Two

hundred years ago this would have been a ride on horse back, or in a

chaise, of eight miles, and over a rough road. Now it is a trip of

three or four miles, accomplished luxuriously in less than half an

hour. When the Subway (now building) is finished, it may be

made in half that time. Cotton Mather would have shuddered at the

change; and yet the university is now so large and so completely a

little world in itself, that even the proximity of Boston can hardly

ruffle its composure or divert its scholastic energies.

BROOKLINE

Brookline

is the richest suburb of Boston and in many respects the most

attractive, with numerous beautiful estates and tasteful “villas”

and charming drives. During all the years since its population

entitled it to a city charter, its people have steadfastly refused to

give up their primitive government by the New England town meeting,

just as they have declined all propositions looking to annexation to

Boston, although their territory is embraced on three sides by the

encroaching municipality. It began, however, as a possession of

Boston. As “Muddy River,” so first called from the stream which

still bears the name and contributes no little to the attractiveness

of the Fenway section of the Boston City Parks System, its fertile

fields were originally utilized by the chief settlers at Boston as a

“grazing-place for their swine and other cattle, while corn” was

on the ground in Boston. For a time, through this usage, it was known

as “Boston Commons.” It was set off as an independent town only

in 1705, when the name of Brooklyn was given it, and its inhabitants

were “enjoyned to build a meeting house and obtain an Orthodox

minister,” — so closely were civic and ecclesiastical

prerogatives blended in the government then.

We

may reach Brookline from Boston easily, quickly, and cheaply by

several routes. The Newton Circuit line of the New York Central

Railroad (South Station, or Trinity Place Station, a few steps from

Copley Square) skirts and traverses the town, and has four

stations within its borders. Various trolley lines cover it more

generally, — via Tremont Street and Roxbury Crossing to Brookline

Village; via Boylston and Ipswich streets and Brookline Avenue to the

same point; via Beacon Street to the Chestnut Hill reservoir; via

Huntington Avenue and Brookline Village to several destinations. For

the purpose of rapid exploration the trolley is superior to the steam

railway, and the last-named line is the most convenient. In the

Subway, or on Boylston Street or Huntington Avenue, or at Copley

Square we may take any outward-bound car bearing the legend

“Brookline Village via Huntington Avenue.”

|

Leaving

Copley Square we soon pass the succession of notable buildings about

and beyond Massachusetts Avenue, and presently traverse a somewhat

open territory, observing, as we pass, the Opera House, the Museum of

Fine Arts, and other institutions. On the

left, overlooking the expansive grounds of the Base Ball Club,

southward, we get a fair view of the roofs and towers of the Roxbury

district of the city. On our right, beyond the expanse of land

reclaimed from the primeval salt marsh, we catch glimpses of the Back

Bay Fens, part of the Boston City Parks System (ultimately to be

developed into a region of rare beauty but now in spots forlorn),

which follow the general course of the tortuous Muddy River from its

mouth at the Charles to a point near Brookline Avenue, where they

narrow into the Riverway. The Riverway, passing out from the Fens,

follows the line of Muddy River through Brookline into Leverett Park,

which connects with Jamaicaway leading to Jamaica Park and pond in

the Jamaica Plain district of the city. Here connection is made with

the Arnold Arboretum, or Bussey Park, West Roxbury district (the

territory of the Bussey Institution, Harvard University), which in

turn connects with the extensive Franklin Park lying between the

Roxbury, West Roxbury, and Dorchester districts. Thence this lovely

chain of parkways and parks from the Back Bay district is continued

by Dorchesterway and the Strandway to Marine Park at City Point,

South Boston. The most important part of the Riverway, including the

main driveway, lies within the city limits, while some of its most

charming features and scenic effects are found in the Brookline

section. It is crossed by Brookline and Longwood avenues. Tremont

Street separates it from Leverett Park.

|

Agassiz Bridge in the Fens |

Near

the Tremont entrance to the Fens from Huntington Avenue we get a

view, on the right, of Fenway Court and Simmons College. Next in our

immediate neighborhood, also on the right, appear the

cluster of high-grade public school houses, and the fine assemblage

of Harvard Medical School buildings described in earlier pages. (see

pp. 91 E, 91 F). A little farther on we pass the House of the Good

Shepherd, a worthy Catholic institution for the shelter and

reclamation of wayward women and girls, — the large brick structure

set in ample grounds.

As

we cross the Riverway just at the foot of Leverett Pond, into

which the river here widens, a pleasing vista opens out to the left.

On either side of the tranquil lake are superb driveways, which of a

pleasant afternoon are crowded with vehicles. A few rods farther on

we are brought to our immediate destination, Village Square,

where free transfers to other trolley lines may be made. Since our

present object is to see something of the historical side of

Brookline, as well as the part wherein is most exhibited the progress

attained in the art of the landscape architect, we will here transfer

to another car. We may remark in passing that on the left of the

street (Washington) by which we entered the square stood in the old

days the “Punch-Bowl Tavern,” built about 1730, — before the

Revolution a favorite junketing place for British officers from the

Boston garrison, and for nearly a century the stopping place of the

stagecoaches for Worcester and other inland towns, and for the great

goods wagons, the pioneers of our modern freight trains.

Boylston

Street, originally the Worcester turnpike, branches off to the

left, and since the Ipswich Street line of cars from Boston,

mentioned above, continues out through this street, we will take one

of them for the rest of our journey in this direction. For a little

way the street is lined with buildings more utilitarian than elegant,

but soon we pass on the left the immense and modernly complete

William H. Lincoln Schoolhouse and enter upon a region of

large and imposing estates, rising to either side of the road on the

great pudding-stone ledges, the country rock of all this section. In

two or three minutes more we come face to face with the granite

gatehouse of the old Brookline Reservoir (fifty years ago the

chief distributing basin of the Boston Water works), still in

service, though its capacity is diminutive as compared with

reservoirs of later date or with the needs of the city.

Here

we will leave the car for a stroll over carless streets in

Brookline’s choicest parts. We take Warren Street up the

hill to Walnut Street, the first turn to the left. On either

side are handsome dwellings with generous grounds, and on the far

corner of Walnut Street stands the fine stone church of the

old First (Unitarian) Parish. A little way below, on Walnut Street,

is the ancient Town Busying Ground, lying close to the

sidewalk, a serene old-time inclosure encompassed by modern

structures, with mounds and vales, rural paths and venerable trees.

Near the street, one of the highest of the mounds contains the tombs

of the Gardner and Boylston families, both prominent in Brookline

town history. Perhaps the most eminent Boylston who lies here was Dr.

Zabdiel Boylston, who introduced in America the practice of

inoculation, as the tablet’s extended inscription relates. He died

in 1766, aged 87. The slab over the Gardner tomb contains thirty

names, among them that of the single minuteman from Brookline killed

at Lexington. A near-by ancient headstone informs that the widow of

the Rev. Increase Mather of Boston lies buried here.

Returning

to Warren Street (named for the famous Boston surgeon, Dr.

John C. Warren, who owned the lands through which it winds), we may

continue for a mile or more between splendid estates with stately

houses set in velvety lawns fringed with trees. At the opening of

Dudley Street is the fine old “Clark house,” built early in the

nineteenth century, latterly the home of Frederick Law Olmsted,

the noted landscape architect, to whose skill a good part of the town

owes much of its beauty. The extensive country seat beyond it,

covering many acres, is the Gardner place, that of the late

John L. Gardner; and on the left hand is the beautiful Sargent

place, the estate of Professor Charles S. Sargent, perhaps the

richest in the town as regards landscape.

At

Cottage Street Warren Street turns off abruptly to the right and,

after a somewhat erratic course, loses itself in Heath Street, which

emerges upon Boylston Street just above the Reservoir. On the

right-hand farther corner of Cottage Street is the unique and

celebrated old Goddard house, whose huge chimney bears the

date 1730. Its quaint architecture, the old-fashioned garden which

surrounds it, and the beautiful trees and shrubs which form its

setting, make it one of the most worthy memorials of Province days.

Next beyond, on the Warren Street side, is the castlelike country

house of the late Barthold Schlesinger, behind noble trees and

dominating a grand expanse of diversified landscape. Joining this

extensive estate is the equally noteworthy Winthrop place, the

former country seat of the late Hon. Robert C. Winthrop, its lands

stretching to Clyde Street. A little farther along, on the left, is

the Lee place, long the summer home of the late Henry Lee, a

sterling Bostonian of his day; on the right, the Augustus Lowell

estate, — these among others; and where Warren Street ends in

Heath, the Theodore Lyman estate, named by some authorities

forty years ago as the finest of modern country seats in this region.

We

skirt this beautiful place as we continue through Heath Street.

Turning down Boylston Street to the right, we soon see on the

opposite (north) side of the way Fisher Avenue, which climbs

over the hill of the same name on top of which are two reservoirs,

one belonging to the city of Boston, the other to the town of

Brookline. On the lower corner of Boylston Street stands the stately

residence of Henry M. Whitney, its sides mantled in ivy.

On a

shaded slope, a little below, is the old Boylston house,

occupying the site of the original homestead of the family, which was

once almost seignorial in this town. Its head was Thomas Boylston,

2d, a surgeon who settled here in 1665, and whose son was the eminent

Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, whose monument we saw in the old burying

ground. One of the daughters was the wife of John Adams and mother of

the second President of the United States. Dr. Zabdiel Boylston built

the present house. During the Revolution it sheltered some of the

patriot troops.

At

Cottage Street, on our route through Warren, we might have turned off

to the south for a walk to Jamaica Pond and Park (Boston City Parks

System), something more than a half mile distant; and at Clyde Street

we might have taken a stroll southwest for three quarters of a mile

to Clyde Park, the property of the Boston Country Club,

where the most fashionable racing events and golf and tennis matches

here abouts take place. But there is more to see in the northern part

of the town.

Accordingly

we take a car back to Village Square, changing there to one bearing

the legend “Newton Boulevard.” This conveys us along Washington

Street, through the business center, past the post office, the steam

railroad station, — trains cross underneath the street, — the

fine granite Town Hall, and the new Public Library building

(capacity of this library, 100,000 volumes) on the right. We now

enter upon a region of ample, homelike-looking houses, generously

encompassed by well-kept grounds.

To

our left we see Aspinwall Hill rise sharply, its sides here

and there showing open patches of pleasant lawn among the

tree-embowered estates. An occasional break in the line of front

walls inclosing the Washington Street properties accommodates a “path

“of steep stairs leading up to Gardner Road, the first of the

series of streets partly encircling the hill. Many others there are,

in sweeping curves or crescents, entering upon and continuing short

bits of straight highway. The landscape architects have happily

avoided the mistake of trying to lay out a swelling hilltop in

rectangles.

We

may alight at Gardner Path, hedge, and vine-bordered, which

will bring us up to the most picturesque part of Gardner Circle.

To our left is the Blake estate, occupying part of the

original Muddy River farm of the Rev. John Cotton, the early colonial

minister of the church in Boston. Above, on one of the most sightly

parts of the slope, stood, until within a year or two, the old

Aspinwall house, shaded by fine elms. Its site now bears a

modern mansion. Dr. William Aspinwall, who built it in 1803, was a

notable physician in his day, a minuteman from the town, and a

patriot all through the Revolution. His house — a grand one in its

period, and to its last day a dignified, ample structure — was once

the only dwelling on this side of the hill, and commanded the whole

sweep of the Charles River and the then distant town of Boston in its

outlook. Ascending to the top of the hill, if we desire, by a sort of

switch-back arrangement of curving and gradually rising roads, we

pass many attractive residences, mostly modern, our highest point

being reached on the S-shaped Addington Road, two hundred and

forty feet above sea level. From here, so far as the breaks between

the rows of apartment houses will permit, we catch glimpses of

country hills to the south, and of the village at our feet; to the

north, across the Beacon Street Boulevard, rises Corey Hill,

two hundred and sixty feet high, formerly part of the extensive farm

of Deacon Timothy Corey, now covered with showy modern estates.

We

can descend to the boulevard in a few minutes by Addington Path and

Winthrop Road, and take any Newton Boulevard car, west bound,

which will convey us shortly to Beacon Circle, directly facing

which is the high embankment and gatehouse of the Chestnut Hill

Reservoir, through which flows a great part of the water supply

of Boston. Here to the left is the High-Service Pumping Station,

a group of solid buildings of some architectural merit, especially

when seen across the beautiful expanse of waters making up the

reservoir. The pumps are among the largest and finest of their class.

From

this point our car turns to the right through Chestnut Hill

Avenue, along the eastern edge of the reservoir, and immediately

we reenter Boston. To our right are various roads with English and

Scotch names, making up the Aberdeen District, an attractive and

healthful addition to the city’s “sleeping room,” lately built

up in the midst of what was primeval forest and ragged ledges of

pudding stone. To our left, as we turn into Commonwealth Avenue,

the grounds surrounding the twin lakes of the reservoir have been

taken by the Metropolitan Water Board and converted into the

Reservoir Park, one of the most restful and charming

pleasure

grounds to be found in the neighborhood of any great city. All around

the winding outlines of the basin runs a trim driveway, and beside it

a smooth gravel footpath. On all sides of the lake are symmetrical

knolls, covered with forest trees and the greenest of turf. The banks

to the water’s edge are sodded and bordered with flowering shrubs;

and the stonework, which in one place carries the road across a

natural chasm, and the great natural ledges, are mantled with

clinging vines, and in autumn are aflame with the crimson of the

Ampelopsis and the Virginia creeper. On the southern side, close to

the narrow isthmus dividing the upper from the lower lake, stands a

classical gatehouse, and behind it Chestnut Hill rears its

wooded mass, crowned with some attractive dwellings. A pleasant,

shaded road winds to the hilltop, which commands a noble prospect.

Our

car continues along Commonwealth Avenue, which here crosses a

high ridge. To the right the view embraces a pretty stone chapel,

thrifty truck patches sloping away from our feet, a deep, verdant

valley, with Strong’s and Chandler’s ponds nestling in its

greenery. At the foot of the hill below us stands the Catholic

Theological Seminary of St. John, a cluster of buildings

imbedded in noble trees. The estate which it occupies was once an

extensive country seat, known as the Stanwood place, comprising many

acres of beautiful wooded land; and much of its beauty in woodland

has wisely been retained. On our left we pass Evergreen Cemetery, and

beyond several handsome estates set well back from the street. At the

foot of the hill, Lake Street, we reach the boundary line of

the city of Newton, and here is a little transfer station, where we

change to a car of the Commonwealth Avenue line, which

traverses the beautiful extension of the famous Boston avenue, —

this part called the Newton Boulevard, — leading to various

sections of Newton and to the country town of Weston.

THE

NEWTONS AND WESTON

Along

Newton Boulevard to the Newtons and Weston. From the transfer

station at Lake Street (reached by all electric cars from the Subway

or Copley Square marked “Newton Boulevard”) our car first climbs

the long slope of Waban Hill, the highest of Newton’s many

hills — three hundred and twenty feet, — lined with modern houses

whose chief recommendation is the charming outlook which they enjoy.

On the summit, to our right, is the reservoir of the city of Newton.

From this point the road stretches out in graceful, sweeping curves

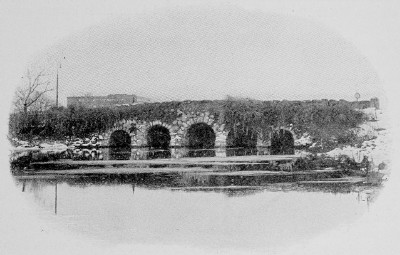

for about five miles, to the old stone bridge crossing the Charles

River to Weston, at nearly the westernmost apex of the town. The

road is practically perfect, — a broad, smooth driveway on either

side of a turfed and shaded park through which the double tracks of

the trolley line run, permitting of high speed. Advantage has been

taken of the naturally diversified configuration of the country to

make the highway as picturesque as possible, and we smoothly climb

lofty ridges, gayly swing down their farther slopes, wind around the

shoulders of swelling knolls, and whirl through shady forest depths

in as much comfort and with nearly as much speed as the occupants of

the many automobiles which find this their most delightful trip out

of Boston.

We

pass between the villages of Newton, Newtonville, and West Newton on

our right; Newton Center, Newton Highlands, and Waban on our left,

and through one edge of Auburndale, which here skirts the river. Our

terminus is the favorite pleasure ground called Norumbega Park,

where the trolley company has provided on the shore of the stream a

variety of attractions for many tastes, — an open-air theater, an

extensive menagerie, a café, and a large boathouse, where

canoes and rowboats may be hired. A launch plies the river between

the park and Waltham, making hourly trips daily, afternoon and

evening.

Canoeing

is the all-engrossing sport on this part of the river, and just

around the bend to our left is the Riverside Recreation Ground. We

cannot see it, for a high wooded promontory shuts off our view; but

we may take a canoe and paddle up through the stone arch of the

Weston Bridge, and in a few minutes we shall be in the

thick

of the fleet at Riverside, where on a pleasant afternoon or

evening the water is often so densely covered that one might almost

cross the stream by stepping from one canoe to another. Frequently

during the summer the fleet parades, decorated with lanterns,

bunting, and flowers, and various water fêtes are held at odd

times. The grounds and boathouses are extensive and well equipped;

and near by are the houses of the Newton Boat Club, the Boston

Canoe Club, and the Boston Athletic Association, whose

large membership helps to swell the crowds upon the river on these

occasions.

As

we stand at the Weston Bridge, looking west, the noble mass of

Doublet Hill, with its twin summits respectively three

hundred

and forty and three hundred and sixty feet high, rises directly

before us. On the hither slope appears the great equalizing

reservoir, having a channel leading to it and great sixty-inch

mains down from it to and across the river, which was constructed by

the Metropolitan Water Board, the work beginning in 1902. A

thirteen-mile aqueduct, much of it tunneled through the rock, brings

the water from the Sudbury dam in Southboro, through Framingham,

Wayland, and Weston, to this new reservoir. The huge mains

constructed during the summer of 1902 along the Newton Boulevard now

convey the additional supply to the Chestnut Hill basins.

From

its summit Doublet Hill presents a fine view of the

surrounding country, and its ascent is easy, either by a path through

the wood or via South Avenue (which forms the western

continuation of Common wealth Avenue through Weston and Wayland) and

Newton Street, which branches off a little to the right

and

leads to Weston village and the station of the Boston & Maine

Railroad. If we take the latter course we shall pass the residences

of many professional and business men, who find Weston a quiet

and healthful home. Thus far the trolley road has not invaded the old

town; but the selectmen have granted a franchise lately to a company

which proposes to build from Waltham, and very soon the ubiquitous

electric cars will be whizzing and clanging through the shady

streets, so long sacred to private vehicles.

To

the left of South Avenue, East Newton Street pursues a winding

course to the river at Newton Lower Falls, a factory village,

where one may take a train for Boston if he so desires. On the way

one passes “Kewaydin,” the extensive estate of Francis

Blake (inventor of the Blake telephone transmitter), a castellated

structure standing on a high, stone-walled hank.

But

probably the most generally interesting spot to be reached by a short

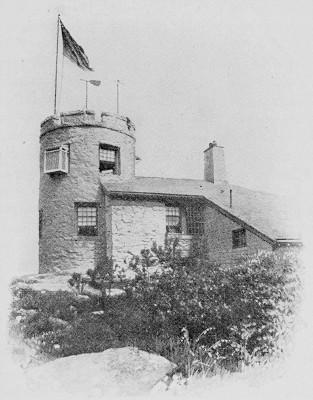

walk from Weston Bridge is the famous Norumbega Tower, built

by the late Professor Eben N. Horsford to commemorate the site of the

Norsemen’s fort founded by Leif Ericson about the year 1000, as

Professor Horsford held. He elaborately carried out his

identification of Watertown with the Vinland of the Northmen, and

traced their wharves, canals, docks, and walls along the river to

this point, the site of their stronghold, where may still be seen —

at least the professor saw them — the remains of the moat and dam

which the Northmen constructed. On this walk a short distance up

South Avenue we take the first turn to the right, River Street, and

follow that street along the riverside for about half a mile, to the

mouth of Stony Brook, which divides Weston from Waltham. The

tower is a structure of field stone, with an inside staircase giving

access to a lookout at the top, and it bears a tablet upon which is

inscribed a detailed description of the Norsemen’s works according

to Professor Horsford’s theory.

Here

the waters of Stony Brook are collected by a dam across the

mouth of the narrow gorge, forming one of the reservoirs of the city

of Cambridge. Beyond it, the towering bulk of Prospect Hill, in

Waltham, cuts off further view in this direction. We might reach

Prospect Hill by a walk of about three miles, but it would

be

better to return to Norumbega Park and Boston.

The

Northern Newtons. By way of varying our route and seeing some

thing of the northern Newtons, we will take a red car, which

turns off the boulevard at Washington Street and follows that

chief thoroughfare of this section down the steep incline through

West Newton, a convenient and — away from the railroad — a pretty

residential section. This is also the civic center of Newton, the

City Hall standing near the New York Central Railroad

station.

We pass it soon after reaching the foot of the hill, Washington

Street swinging around to the right and hence forward following the

steam railroad tracks. These were depressed a few years ago, at great

expense, so as entirely to eliminate grade crossings — of which

there were many — throughout the city. This street is the chief

business avenue all along through Newtonville to Newton, —

anciently Newton Corner, — where our line ends and we may transfer

to cars for other villages or for Boston, via Brighton and

Commonwealth Avenue.

Taking

one of the latter, a ride of less than five minutes through Tremont

Street brings us to Waverley Avenue, where we alight if we

wish to see the Eliot Monument, commemorating the first

preaching to the Indians by John Eliot, “the apostle.” It is

rather a stiff climb up Waverley Avenue to Kenrick Street (on the

left), and a few minutes’ walk along Kenrick Street to a lane on

the right, which leads a few steps down to the unique monument, — a

handsome balustraded terrace, on the face of which are set tablets

bearing the names of Eliot and his associates, and this inscription:

Here

at Nonantum, Oct. 28, 1646, in Waban’s wigwam near this spot, John

Eliot began to preach the gospel to the Indians. Here he founded the

first Christian community of Indians within the English colonies.

The

view from the top of the terrace is very fine. It embraces much of

the ground which we traversed on our way out from Boston, including

the wooded slope of Waban Hill just opposite, Strong’s and

Chandler’s ponds in the valley to our left, and St. John’s

Catholic Seminary in its grove close beside the Boulevard.

We

may, if we wish, cross over Waban Hill via Waverley and Grant

avenues, returning to Lake Street transfer station, and choose one of

two or three pleasant routes back to the city. The cars via

Coolidge’s Corner and the Beacon Street boulevard

will show us all the latest triumphs of the builder’s art in blocks

and apartment houses; those via Commonwealth Avenue will take us

swiftly over a magnificent ridge, — the northwestern end of Corey

Hill, — from the top of which a sweep ing view is had of Boston,

Cambridge, and many towns beyond. The road is winding and runs up

hill and down dale, like its Newton prolongation; and since it is not

largely built up as yet, and there are few intersecting streets, our

speed is but little less than that of the automobiles which make this

a favorite course. Either car we may take will soon bring us back to

Copley Square or the Subway.

Newton

was originally part of Cambridge, but in 5695 was set off as Newton

by the General Court, its previous designation having been Little

Cambridge. Its Indian name of Nonantum is perpetuated in one of the

least attractive of its many villages, — a manufacturing hamlet on

the north side, separated from Watertown only by the river. The area

within the city limits is nearly thirteen thousand acres, and its

contour is very diversified, a number of fine hills rising to heights

of from two hundred to three hundred and twenty feet. The Charles

River forms the meandering boundary line, separating Newton from

Watertown, Waltham, Weston, Wellesley, and Needham, successively. The

main line and also the Newton Circuit branch of the New York Central

Railroad traverse the city and serve the various sections with a

dozen stations. A number of electric lines, radiating mostly from the

business center, — anciently Newton Corner, now plain Newton, —

thread all sections.

NEWTON

AND WELLESLEY

The

many trolley lines radiating from Boston to all its suburbs make it

easy to reach widely separated places of interest in a single

afternoon, or at most in a day. In such a trip could be included the

southern Newtons, Wellesley, Natick, Needham, Waltham, and Watertown.

The territory embraced in these places is very extensive; but if,

instead of describing the wide arc of a circle including them, one

traverses several chords of that arc, the various points are easily

and rapidly covered.

Essaying

first the southernmost of these chords, we may take a Boston &

Worcester car in Park Square, thence ride out through Brookline and

Newton via Boylston Street and its continuations in Wellesley, almost

in a bee line to Natick; or we may take at the Subway a car for the

Reservoir, marked Newton Boulevard, and change there for a car

passing along the Newton Boulevard to Washington Street, Newton;

thence to the left through Auburndale and the “Lower Falls” to

the same destination.

If

we choose the route last mentioned, — by way of the Newton

Boulevard, — our course from the intersection of the Boulevard and

Washington Street, in Newton, is up quite a steep rise, past

the Woodland Park Hotel on the right, — a roomy, wooden building,

in wide-spreading, shaded grounds. At the next street opening above

we get a glimpse of the large building of the Lasell Seminary,

a noted school for girls; and a little farther on we cross the track

of the Newton Circuit steam line, the Woodland station being close at

our right. We pass attractive houses by the way, nearly all

surrounded by generous grounds and several shaded by natural forest

trees. As we cross Beacon Street we pass the Newton Hospital, an

excellent example of the cottage type of such institutions, standing

in large and well-kept grounds.

Our

course continues in the same general direction, southwest, to Newton

Lower Falls, a small, conventional factory village, where the

water power of the Charles River has been utilized to propel woolen

mills and one or two paper mills since about 1790. An ancient burying

ground here contains the graves of Revolutionary soldiers.

At

this point we cross the river and enter the town of Wellesley.

For the rest of our way the trolley track parallels the main line of

the New York Central Railroad. That part of Wellesley through which

we first pass is locally known as “The Farms,” though the

village and railroad station are some distance to our right.

Wellesley is by nature one of the most picturesque towns in eastern

Massachusetts, and its natural beauties have been enhanced by the art

of the landscape architect.

As

we continue along Washington Street, to our left rises Maugus

Hill, three hundred feet high, on top of which is the town

reservoir. About a mile from the town line we pass the neat stone

Wellesley Hills station of the steam railroad, which just

above has made its way through a deep rock cutting in the high ledge.

Above the station is the Wellesley High School building.

Beyond is an attractive stone church (Unitarian). Nearly a mile

farther, in a picturesque inclosure of ten acres, shaded by fine

trees and bordered on its hither side by a gurgling brook overhung

with water willows, stands the Wellesley Town Hall and Public

Library building, a gift to the town by the late H. Hollis

Hunnewell, all complete, in 188x, when the town was set off from

Needham and incorporated (its name being taken from Mr. Hunnewell’s

notable estate, which in turn was named from Mrs. Hunnewell’s

maternal grandfather, Samuel Welles, who about 1750 owned the place).

The Town Hall is of stone, in the style of a French chateau, with

porch facing the square, surmounted by a clock. The library is a

distinct part of the building, with a separate entrance.

A

short distance beyond we come to Wellesley Square, where is

the Needham trolley line. Here carriages may be taken for a drive to

the Hunnewell estate, which is generously open to the

public.

An hour may profitably be given to visiting it. The grounds embrace

five hundred acres, of which sixty acres nearest the house have a

frontage on the beautiful Lake Waban, named for the Indian

chief who was Eliot’s first convert. Two long avenues of fine trees

extend from the public way to the house, on one side of which is a

vast lawn, on the other a French parterre, or architectural garden.

Broad flights of stairs lead down therefrom to the parapet wall along

the lake front, through successive terraces with evergreens on either

side, trimmed into various fanciful forms. Along the lake shore is an

Italian garden, with prim array of formal clipped trees. Great hedges

of hemlock and arbor vita, fine vistas down avenues of purple beeches

and white pines, extensive conservatories, and a graceful azalea

tent, all add to the charm of the place.

Near

by is the Robert G. Shaw estate, a picturesque mansion house

set among fine trees and surrounded by beautiful lawns. Not far away

— just where the Charles River in one of its most sinuous bends

forms the boundary line between Wellesley and Dover — is the Cheney

place, country seat of Mrs. B. P. Cheney, widow of a pioneer in

the express business of America and in transcontinental railroads, an

estate of two hundred acres. The views up and down the river here

enhance the natural beauties of the land, which is highly

diversified. The estate is laid out in a mingling of lawns, flower

gardens, woods, groves, meadows, and fields. The five great elms

which surround the house, tradition says, were brought from Nonantum,

now Newton, and planted here by one of the friendly Indian tribe whom

Eliot taught. The lawn of six teen acres, inclosed by fine hedges, is

one of the noteworthy features.

Still

farther south — indeed almost at the southern boundary of the town,

where Ridge Hill, two hundred feet high, slopes to the placid waters

of Sabrina Pond — is the famous Ridge Hill farm, of eight

hundred and seventy acres. This attained most of its fame during the

life time of a former owner, William Emerson Baker, who made a

fortune in sewing machines, and who delighted in giving great fêtes

here on occasion, providing for the amusement and mystification of

his guests various surprises, droll and bewildering, sumptuous

feasts, and odd sports.

But

Wellesley’s chief fame lies in Wellesley College, for women,

which crowns the rounded hilltops on the north side of Waban Lake,

toward which its 300 acres of grounds gently slope. On the

lake

are the college boathouses, whence on “Float Day” go forth the

class crews of young women to show off their prowess as oarswomen

before the admiring gaze of relatives and friends ashore. The college

is at the left of Central Street, through which our car continues on

its way to Natick. A short distance beyond the square, as we cross

Blossom Street, we catch the first glimpse of the buildings and pass

Fiske Cottage at one of the entrances to the grounds, A little

beyond, the white dome and low, square building of the new

observatory — gift of Mrs. Sarah E. Whitin of Whitinsville — cap

a gentle hillock. As we near the North Lodge, opposite, across the

valley, on the crest of a fine ridge, stands College Hall, the main

building, designed by Hammatt Billings. Its ground plan is a double

Latin cross, and its façades are broken by bays, pavilions,

and porches, topped by towers and spires. Within, the great central

hall is open to the glass roof, eighty feet above. In this building

are the college offices, the library, the original chapel, class and

lecture rooms, and laboratories; also dormitories and a dining-room.

Other

buildings are Stone Hall, gift of Mrs. Valeria G. Stone of Malden,

devoted to botanical work and dormitories, on another knoll

overlooking the lake; the Farnsworth Art Building, gift of Isaac D.

Farnsworth of Boston, on an eminence opposite College Hall; the Music

Hall, the Memorial Chapel, gift of Miss Elizabeth G. and Mr. Clement

S. Houghton of Boston; the Chemistry Building; a group of dormitories

of Elizabethan architecture; Mary Hemenway Hall, with the Gymnasium:

the dormitories and the gymnasium completed in 1910. The main avenue

winds through woodland and meadow from College Hall to the East Lodge

at the entrance on Washington Street.

Wellesley

College was founded by the Hon. Henry F. Durant, formerly a

conspicuous member of the Massachusetts bar, who died in Wellesley in

1881, aged fifty-nine. The greater part of his fortune was devoted to

its establishment as a non-sectarian institution for the purpose “of

giving to young women opportunities for education equivalent to those

usually provided in colleges for young men.” In this work he had

the ardent coöperation of his wife, Mrs. Pauline Adeline (Fowle)

Durant, who continues, since his death, her devotion to the work

which jointly they planned. The college was chartered in 1871 and

formally opened in 1875. The scheme of its founder included these

features: a faculty of women and a selected board of trustees

composed of both women and men, in whom the property of the college

and its official control should be vested.

Our

car passes for nearly a mile along the northern side of the college

estate, and at the farther end stands another lodge at its western

entrance.

NATICK

AND NEEDHAM

We

continue along Central Street and soon cross the line into the town

of Natick. At our left rises Broad’s Hill, three

hundred feet high; at our right is the railroad, close alongside. We

reach Natick station in fifteen minutes from Wellesley Square. The

village is chiefly devoted to shoe manufacturing. Here is the Morse

Institute Library, founded by the bequest of Mary Ann Morse, who

died in 1862. It was dedicated on Christmas day, 1873. Here also is

the former homestead of Henry Wilson, the “Natick cobbler,”

as he was known for many years, who rose from the shoemaker’s bench

to the Senate of the United States and the Vice Presidency. It is a

roomy, plain house of wood, painted white, standing back a little way

from the street, under majestic elms. In the square near the station

is the Soldiers’ Monument of the Civil War, flanked by brass

siege guns.

A

branch trolley line runs hence to Needham, and if we desire to see

more relics of the Indian apostle Eliot, we may take the car to South

Natick, only a mile and a half southeast. On the way we pass over

Carver Hill, two hundred and eighty feet high, whence a

splendid view of the upper Charles River country is gained. In the

South Natick village center was the Eliot Oak, under which,

tradition says, Eliot preached his first sermon to his then newly

established plantation of praying Indians, in 1650. Here he did much

of his work of translating the Bible into the Indian language; and

here, in 1651, his converts built their first schoolhouse and church.

Here, also, are to be seen the Eliot Monument, set up by the

citizens in 1847, and the headstone from the grave of Daniel

Takawambait, the first native minister, set into a granite block

alongside the near-by sidewalk. The Eliot Church (Unitarian)

is the fifth on the site of the rude structure reared by the red men.

It is a typical New England meetinghouse of the early nineteenth

century. It has no connection, except by name and location, with that

founded by Eliot.

South

Natick is said to have been the original Oldtown of Harriet Beecher

Stowe’s “Oldtown Folks.”

From

here to Needham, about five miles, the route lies mostly through a

smiling farming country. We cross the Charles twice within a mile,

and at Charles River Village, which we pass midway, its waters

drive some paper mills. Needham is a quiet, dignified village

of the conventional type, with a fine new high-school building and

one or two other public edifices of brick.

Changing

here to a car for Newton, a ride of a mile north brings us to

Highlandville, the north village of Needham, where a

Carnegie

public library has lately been raised, and where are a couple of shoe

factories. Two miles farther, in a generally northeasterly direction,

the trolley line again crosses the Charles River, which, since

we left it at South Natick, has made divagations into Dover and

Dedham, skirted West Roxbury, and has assumed a path of comparative

rectitude as the boundary line between Needham and Newton.

THE

SOUTHERN NEWTONS

The

railway enters the factory village of Newton Upper Falls, and

traverses several rather depressing streets in the zigzags necessary

for the car to mount the lofty brownstone cliff through which the

river cut its way in ages past, and at the foot of which the village

nestles.

Rustic Bridge and Cave,

Hemlock Gorge |

It

will interest us more if we leave the car just before it crosses the

bridge and take the path, plainly marked, to the left, into Hemlock

Gorge, one of the smallest but most picturesque of the

Metropolitan Park Reservations. Its area is only about twenty-four

acres, but it includes a wild, rocky chasm, through which the swift,

narrow river makes its way, dense thickets, and a grand growth of old

hemlocks towering over all. This park was established in 1895. At its

upper end is the famous Echo Bridge, perhaps the most

photographed bit of masonry in the neighborhood of Boston. It is a

finely proportioned structure, reminding one much of the noted Cabin

John Bridge near Washington, though on a smaller scale. It is the

means by which the aqueduct from the Sudbury River crosses the

Charles on its way to Boston. We may walk across it, enjoying the

attractive outlook over the river, the falls, and the gorge, and

descend by the stone stairs to the bank of the stream and try the

remarkable echoes which give the bridge its name. From the northern

end of the bridge a narrow plank walk between two houses brings us

out to Chestnut Street, where we may again take the car, which, sweep

ing around the right, along the edge of the high cliff, gives a good

view of the village at its foot.

|

The

most direct route from Boston to Echo Bridge and Hemlock Gorge is by

a Boston & Worcester trolley car, which passes over the Back Bay,

through Brook line and Newton, directly to the upper end of the

Gorge, where the deep, black water sweeps through the narrow chasm

close beside the track. Alighting here, one can explore the

reservation in a short time. By this route, also, it is a delightful

ride to Wellesley Hills (where the line crosses that of the Natick

cars by which we came out), and so on to Framingham and Worcester.

Continuing

a mile or so farther, in the same general direction, we cross the

tracks of the New York Central Railroad, and also those of the Boston

& Worcester electric railway, at the neat and busy village of

Newton Highlands. All about on the swelling slopes, in

attractive modem houses, dwell many of Boston’s business men.

Swinging around to the left into Walnut Street, our course is over a

wooded eminence thickly studded with residences. Descending its

farther slope, we pass on our left the Gothic arched entrance of the

Newton Cemetery, one of the most beautiful, by nature and

art,

of any around Boston. A little farther down we see, away to our left,

the great power house of the street railway system.

At

the Newton Boulevard, where is a commodious waiting room, one

may transfer to cars for Boston or to other parts of Newton. We might

take a side trip hence to Newton Center via Homer

Street, but the route is not particularly attractive; a better way to

that pretty village is reached by taking a Boulevard car from Boston,

and changing at Centre Street. This route passes the old burying

ground of the town, where lie the first settlers, a great granite

monument of modern date bearing their names. Of a later period are

the graves of heroes of the French and Indian and Revolutionary wars,

— Major General William Hull, Brigadier General Michael Jackson and

sons, officers in the Revolution, the son and namesake of the apostle

Eliot, and others noted in the early annals of the town. The old

first parish church formerly fronted this ground, and its first

pastor was buried here in 1668. At Newton Center are many beautiful

residences, and on Institution Hill stand the buildings of the Newton

Theological Institution, founded by the Baptists in 1826, as a

training school for the ministry. Its grounds are extensive, and the

view in all directions is inspiring. Within the past few years, under

the presidency of the Rev. Nathan E. Wood, D.D., much money has been

added to the funds of the school, a new library, chapel, and

dormitories have been built, and the whole hilltop has been laid out

in most attractive landscape style. At the foot of the hill lies

Crystal Lake, as the former Wiswall’s Pond is known. It was named

from old Elder Wiswall, in whose homestead it was included. A

splendid road around its shores is one of the attractions of “the

Center.” The stone Baptist church, of Romanesque architecture, is

one of the finest in Boston suburbs.

But

our car is bound north, to Newtonville, and immediately after

crossing the Boulevard we pass a forest-covered hill on the left,

while to our right is a deep, shady valley, through which brawls a

swift brook down rocky ridges. It is a charming section, and some of

the prettiest homes of the city are along this way. One famous estate

which we soon go by is Brooklawn, once the home of General

Hull, of Revolutionary fame; since 1854 that of ex-Governor William

Claflin, who has dispensed hospitality to many distinguished guests

here. Just beyond, on the left, is the stately High School; on

the other side, the Claflin School; and again on the left, the

attractive house and grounds of the Newton Club. A little

farther on we come to the business center of Newtonville, where we

cross the New York Central tracks and Washington Street. Here change

may be made for Newton proper and most of the other villages. Soon we

turn into Watertown Street and pass through the village of Nonantum,

where on the left are the Nonantum worsted mills; also a tiny pond,

bearing the lofty title of Silver Lake.

In

a few minutes, turning sharply to the right, we are in Galen Street,

in the small corner of Watertown lying south of the Charles,

leading to the broad new bridge, replacing an old-time one, by which

we are to cross into Watertown Square.

As

we cross the grand stone bridge we miss the granite tablets which

were on either side of the old bridge. These were erected by the late

Professor Eben N. Horsford, one of them to mark his Norsemen

sites, — that on the left inscribed “Outlook upon the stone

dam and stone walled docks and wharves of Norumbega, the seaport of

the Northmen in Vineland.” The other had this inscription: “The

old bridge by the mill crossed Charles River near this spot as early

as 1641.”

WALTHAM

It

is but a few steps to Watertown Square, where cars from Boston

and Cambridge arrive by several routes, and where we change to a car

for Waltham. Our course all the way is along old Main Street,

to the foot of Prospect Hill, at the terminus of the route.

Here we alight and, following the plain directions on guideboards,

climb, first by the street crossing the Central Massachusetts

Division of the Boston & Maine Railroad, and afterward by a

winding path through the natural woodland park which the city of

Waltham has made of the upper part of the hill, to its summit. From

the outlook, four hundred and eighty, two feet above sea level —

the highest eminence in the Metropolitan district except the Great

Blue Hill in Milton, — we may see to the north, on a clear day, as

far as Kearsarge (seventy-five miles) and several other mountains of

southern New Hampshire; as well as Wachusett, Watatic, and

Asnybumskit in central Massachusetts. The view embraces all the towns

within a radius of twenty miles or more. In taking this noble hill

and laying it out as a reservation, the city has wisely refrained

from “fixing it up” or making it a “parky” affair. Its

wildness and naturalness are its chief charms.

Returning

to Main Street, we will take a car for about a mile east, passing

along the pleasant, shaded thoroughfare, to the Common, on

which stands the Soldiers’ Monument, and near which is the station

of the Fitchburg Division, Boston & Maine Railroad. A branch of

the trolley company’s lines to Newton, by the Moody Street bridge,

crosses the Charles River just south of the Common. On our way down