|

BOSTON: A GUIDE BOOK

I.

MODERN BOSTON

HISTORICAL

SKETCH

HE

town of Boston was founded in 163o by English colonists sent out by

the “Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England,”

under the lead of John Winthrop, the second governor of the Bay

Colony, who arrived at Salem in June of that year with the charter of

1629. It originated in an order passed by the Court of Assistants

sitting in the “Governor’s House” in Charlestown, on the

opposite side of the Charles River, first selected as their place of

settlement. This order was adopted September 17 (7 O. S.), and

established three towns at once by the simple dictum, “that

Trimountane shalbe called Boston; Mattapan, Dorchester; & ye

towne vpon Charles Ryver, Waterton.” “Trimountane” consisted of

a peninsula with three hills, the highest (the present Beacon Hill),

as seen from Charlestown, presenting three distinct peaks. Hence this

name, given it by the colonists from Endicott’s company at Salem,

who had preceded the Winthrop colonists in the Charlestown

settlement. The Indian name was “Shawmutt,” or “Shaumut,”

which signified, according to some authorities, “Living Waters,”

but according to others, “Where there is going by boat,” or “Near

the neck.” The name of Boston was selected in recognition of the

chief men of the company, who had come from Boston in England, and

particularly Isaac Johnson, “the greatest furtherer of the Colony,”

who died at Charlestown on the day of the naming. The peninsula was

chosen for the chief settlement primarily because of its springs, the

colonists at Charlestown suffering disastrously from the use of

brackish water. The Rev. William Blaxton, the pioneer white settler

on the peninsula (coming about 1625), then living alone in his

cottage on the highest hill slope, “came and acquainted the

governor of an excellent spring there, withal inviting him and

soliciting him thither.” HE

town of Boston was founded in 163o by English colonists sent out by

the “Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England,”

under the lead of John Winthrop, the second governor of the Bay

Colony, who arrived at Salem in June of that year with the charter of

1629. It originated in an order passed by the Court of Assistants

sitting in the “Governor’s House” in Charlestown, on the

opposite side of the Charles River, first selected as their place of

settlement. This order was adopted September 17 (7 O. S.), and

established three towns at once by the simple dictum, “that

Trimountane shalbe called Boston; Mattapan, Dorchester; & ye

towne vpon Charles Ryver, Waterton.” “Trimountane” consisted of

a peninsula with three hills, the highest (the present Beacon Hill),

as seen from Charlestown, presenting three distinct peaks. Hence this

name, given it by the colonists from Endicott’s company at Salem,

who had preceded the Winthrop colonists in the Charlestown

settlement. The Indian name was “Shawmutt,” or “Shaumut,”

which signified, according to some authorities, “Living Waters,”

but according to others, “Where there is going by boat,” or “Near

the neck.” The name of Boston was selected in recognition of the

chief men of the company, who had come from Boston in England, and

particularly Isaac Johnson, “the greatest furtherer of the Colony,”

who died at Charlestown on the day of the naming. The peninsula was

chosen for the chief settlement primarily because of its springs, the

colonists at Charlestown suffering disastrously from the use of

brackish water. The Rev. William Blaxton, the pioneer white settler

on the peninsula (coming about 1625), then living alone in his

cottage on the highest hill slope, “came and acquainted the

governor of an excellent spring there, withal inviting him and

soliciting him thither.”

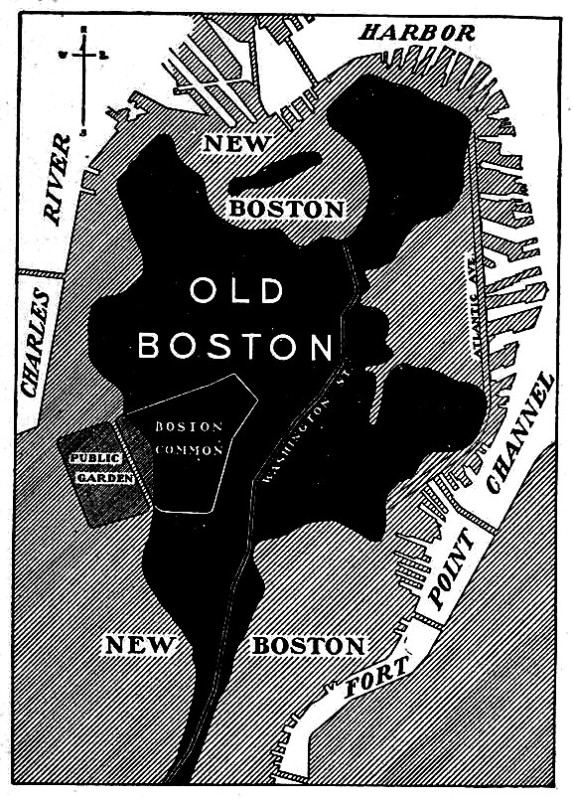

The

three-hilled peninsula originally contained only about 783 acres, cut

into by deep coves, estuaries, inlets, and creeks. It faced the

harbor, at the west end of Massachusetts Bay, into which empty the

Charles and Mystic rivers. It was pear-shaped, a little more than a

mile wide at its broadest, and less than three miles long, the stem,

or neck, connecting it with the mainland (at what became Roxbury) a

mile in length, and so low and narrow that parts were not

infrequently overflowed by the tides. By the reclamation of the broad

marshes and flats from time to time, and the filling of the great

coves, the original area of 783 acres has been expanded to 1801

acres; and where it was the narrowest it is now the widest.

Additional territory has been acquired by the development of East

Boston and South Boston, and by the annexation of adjoining cities

and towns. Thus the area of the city has become more than thirty

times as large as that of the peninsula on which the town was built.

Its bounds now embrace 27-251 acres, or 42.6 square miles. Its

extreme length, from north to south, is eleven miles, and its extreme

breadth, from east to west, nine miles. While the Colonial town was

confined to the little peninsula, its jurisdiction at first extended

over a large territory, which embraced the present cities and towns

of Chelsea and Revere on the north, and Brookline, Quincy, Braintree,

and Randolph on the west and south. So there was quite a respectable

“Greater Boston” in those old first days. The metropolitan

proportions continued till 1640, and were not entirely reduced to the

limits of the peninsula and certain harbor

islands till 1739.

East

Boston is comprised in two harbor islands: Noddle’s Island, which

was “layd to Boston” in 1637, and Breed’s (earlier Hog) Island,

annexed in 1635. South Boston was formerly Dorchester Neck, a part of

the town of Dorchester, annexed in 1804. The city of Roxbury (named

as a town October 8, 1630) was annexed in 1868; the town of

Dorchester (named in 1630 in the order naming Boston), in 1870; and

in 1874 the city of Charlestown (founded as a town July 4, 1629), the

town of Brighton (incorporated 1807), and the town of West Roxbury

(incorporated 1851) were by one act added. These annexed

municipalities retain their names with the term “ District “

added to each. Boston remained under town government, with a board of

selectmen, till 1822. It was incorporated a city, February 23 of that

year, after several ineffectual attempts to change the system.

BOSTON

PROPER

The

term “Boston Proper” is customarily used to designate the

original city exclusive of the annexed parts; but for the purposes of

this Guide we comprehend in the term the entire municipality, as in

business and social relations, but yet independent political

corporations. Together with the municipality these allied cities and

towns constitute what is colloquially known as Greater Boston. This

metropolitan community is officially recognized at present only in

two state departments: the Metropolitan Parks and the consolidated

Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Departments; and in part in the

Boston Postal districts the Metropolitan Parks District is the

largest, comprising Boston and thirty-eight cities and towns within a

radius of thirteen miles towns; the Metropolitan Sewerage District,

twenty-four; and the Boston Postal District, ten. The “Boston

Basin,” however, is regarded as constituting the true bounds of

“Greater Boston.” This includes a territory of some fifteen miles

in width, lying between the bay on the east, distinguished from the

allied cities and towns, closely identified with it District

established by the Post Office Department. Of these several from the

City Hall, having a combined population approximating 1,300,000. The

Metropolitan Water District includes seventeen cities and the Blue

Hills on the south, and the ridges of the Wellington Hills sweeping

from Waltham on the west around toward Cape Ann on the north. It

embraces thirty-six cities and towns. The population of Boston alone

(census of 1905) is 595,380.

The

present city is divided by custom long established into several

distinct sections. These are:

The

Central District or General Business Quarter

The

North End

The

West End

The

South End

The

Back Bay Quarter

The

Brighton District, on the west side

The

Roxbury District, on the south

The

West Roxbury District, on the southwest

The

Dorchester District, on the southeast

The

Charlestown District, on the north

East

Boston on its two islands, on the northeast

South

Boston projecting into the harbor, on the east

The

Business Quarters now occupy not only the Central District, but

extend over most of the North End, parts of the West End and of the

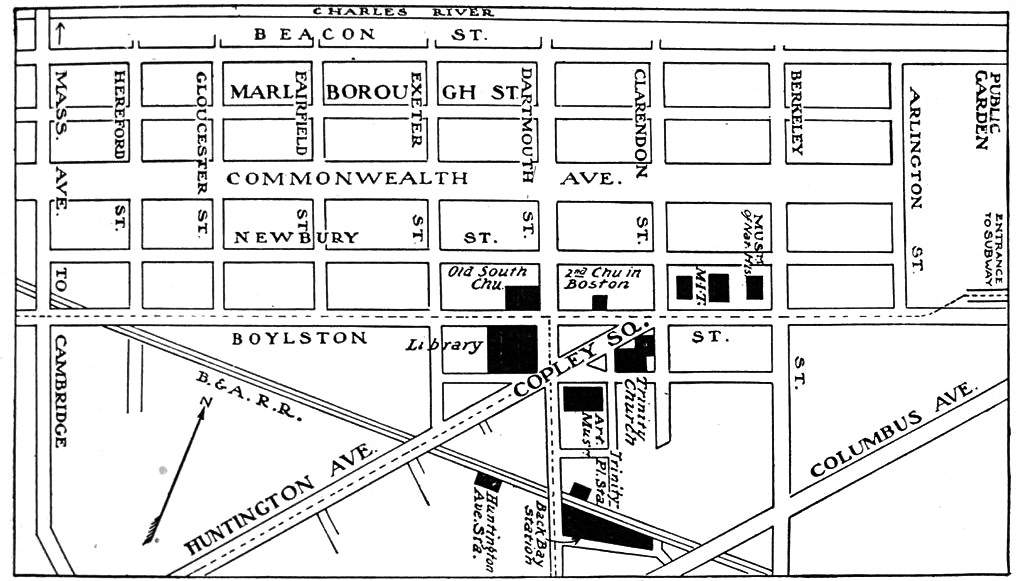

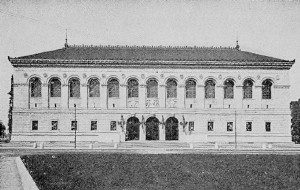

South End, and penetrate even the Back Bay Quarter, laid out in

comparatively modern times (1860-1886), where the bay had been, as

the fairest residential quarter of the city and the place for its

finest architectural monuments.

I.

THE CENTRAL DISTRICT

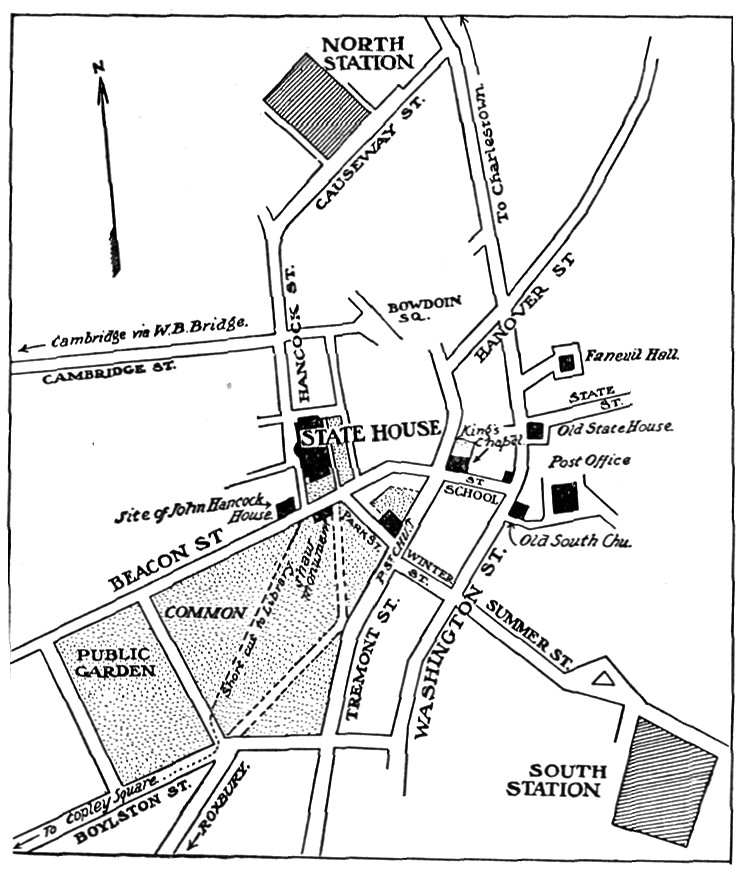

The

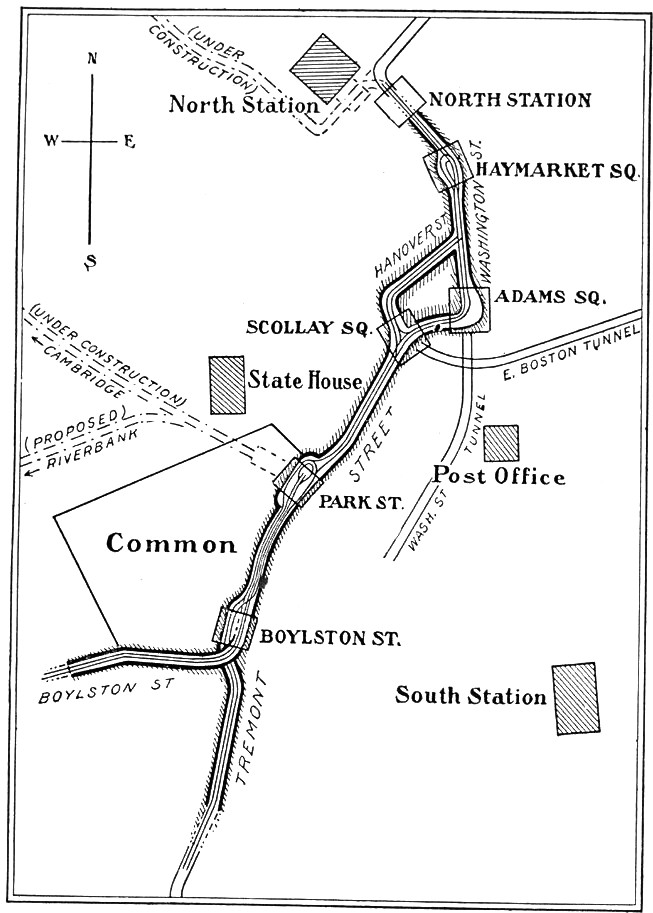

Central District (see Plates II and III) is of first interest to the

visitor, for here are most of the older historic landmarks. This

small quarter of the present city, together with the North End,

embraces that part of the original peninsula to which the historic

town Colonial, Provincial, and Revolutionary Boston — was

practically confined. The town of 1630 was begun along

the irregular water front, the principal houses being placed round

about the upper part of what is now State Street, modern Boston’s

financial center, and on or near the neighboring Dock Square, back of

the present Faneuil Hall, where was the first Town Dock, occupying

nearly all of the present North Market Street, in the “Great Cove.”

The square originally at the head of State Street (first Market, then

King Street), in the middle of which now stands the Old State House,

was the first center of town life. At about this point, accordingly,

our explorations naturally begin.

State-Street

square and the Old State House. Our starting place is the square

at the head of State St., which the Old State House faces. This

itself is one of the most notable historic spots in Boston. For the

first quarter-century of Colony life the entire square, including the

space occupied by the Old State House, was the public marketstead.

Thursday was market day, — the day also of the “Thursday Lecture”

by the ministers. Early (1648) semiannual fairs here, in June and

October, were instituted, each holding a market for two or three

days. Here were first inflicted the drastic punishments of offenders

against the rigorous laws, and here unorthodox literature was burned.

The

Stocks, the Whipping Post, and the Pillory were earliest placed here.

When the town was a half-century old a Cage, for the confinement and

exposure of violators of the rigid Sunday laws, was added to these

penal instruments. In the Revolutionary period the Stocks stood near

the northeast corner of the Old State House, with the Whipping Post

hard by; while the Pillory when used was set in the middle of the

square between the present Congress Street (first Leverett’s Lane)

on the south side and Exchange Street (first Shrimpton’s Lane,

later Royal Exchange Lane) on the north. The Whipping Post lingered

here till he opening of the nineteenth century.

This

square continued to be the gathering place of the populace from the

Colonial through the Province period on occasion of momentous events.

It was the rendezvous of the people in the “bloodless revolution”

of April, 1689, when the government of Andros was overthrown. In the

Stamp Act excitement of 1765 a stamp fixed upon a pole was solemnly

brought here by a representative of the “Sons of Liberty” and

fastened into the town Stocks, after which it was publicly burned by

the “executioner.” On the evening of March 5, 1770, the so-called

Boston Massacre, the fatal collision between the populace and the

soldiery, occurred here, the site being indicated by a tablet on the

building at the Exchange Street corner, northwest.

On

the south side of the original marketstead, by the present Devon

shire Street (first Pudding Lane), where now is the modern Brazer’s

Building (27 State Street), was the first meetinghouse, a rude

structure of mud walls and thatched roof. This also served through

its existence of eight years for Colonial purposes, as the carved

inscription above the entrance of Brazer’s Building relates:

Site of the First Meetinghouse in

Boston, built A.D. 1632.

Preachers: John Wilson, John

Eliot,

John Cotton.

Used before 1640 for town meetings

and

for

sessions of the General Court of the

Colony.

At

the upper end of this side of the marketstead, extending to

Washington Street (first The High Street), were the house and garden

lot of Captain Robert Keayne, charter member and first

commander of the first “Military Company of the Massachusetts”

(founded 1637, chartered 1638), from which developed the still

flourishing “Ancient and Honor able Artillery Company,” the

oldest military organization in the country. A century later, on the

Washington Street corner, was Daniel Henchman’s bookshop, in

which Henry Knox, afterward the Revolutionary general and

Washington’s friend, learned his trade and ultimately succeeded to

the business. When the British regulars were quartered on the town,

in 1768-1770, the Main Guardhouse was on this side, directly

opposite the south door of the Old State House, with the two

fieldpieces pointed toward this entrance.

On

the west side of the marketstead, — the present Washington Street,

— nearly opposite Captain Keayne’s lot, was the second

meetinghouse, built in 1640, the site now occupied by the Rogers

Building (209 Washington Street). This was used for all civic

purposes, as well as religious, through eighteen years.

It

stood till 1711, when it was destroyed in the “Great Fire” (the

eighth “Great Fire” in the young town) of October that year, with

one hundred other buildings in the neighborhood. Its successor, on

the same spot, was the “Brick Meetinghouse” which remained for

almost a century.

North

of the second meetinghouse site, where is now the Sears Building (199

Washington Street), was the house of John Leverett, after ward

Governor Leverett (1673). On the opposite corner, now covered by the

Ames Building (Washington and Court streets), was the home stead

of Henry Dunster, first president of Harvard College.

On

the north side of the marketstead, near the east corner of the

present Devonshire Street, was the glebe of the first minister of

the first church, the Rev. John Wilson, with his house, barn, and two

gardens. His name was perpetuated in Wilson’s Lane, which

was cut through his garden plot in 1640, and which in turn was

absorbed in the widened Devonshire Street.

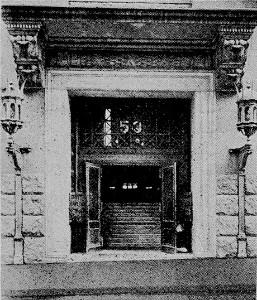

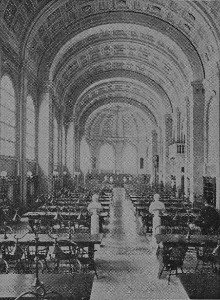

Doorway, Exchange Building |

Looking

again across to the south side, we see the site of Governor

Winthrop’s first house, covered by the expansive Exchange

Building (53 State Street). It stood on or close to the ground

occupied by the entrance hall of the building.

This

was the governor’s town house for thirteen years from the

settlement. Thence he removed to his last Boston home, the mansion

which stood next to the Old South Meetinghouse. The first General

Court — the incipient Legislature — ever held in

America, October 19, 1630, may have sat in the governor’s first

house, the frame of which was brought here from Cambridge, where the

governor first proposed building.

At

the corner of Kilby Street (first Mackerel Lane), where the Exchange

Building ends, stood the Bunch-of-Grapes Tavern of Provincial

times, with its sign of a gilded carved cluster of grapes, the pop

dated from 1711, and was preceded by a Colonial “ordinary,” as

taverns were then called, of 1640 date. In the street before the

Bunch-of-Grapes’ doors, the lion and unicorn, with other emblems of

royalty and signs of Tories that had been torn from their places

during the celebration of the news of the Declaration of Independence

in July, 1776, At the corner of Kilby Street (first Mackerel Lane),

where the popular resort of the High Whigs in the prerevolutionary

period. It were burned in a great bonfire.

|

The

Bunch-of-Grapes was a famous tavern of its time. In 1750 Captain

Francis Goelet, from England, on a commercial visit to the town,

recorded in his diary that it was “noted for the best punch house

in Boston, resorted to by most of the gentn merchts and masters

vessels.” After the British evacuation, when Washington spent ten

days in Boston, he and his officers were entertained here at an

“elegant dinner” as part of the official ceremonies of the

occasion. The tavern was especially distinguished as the place where

in March, 1786, the group of Continental army officers, under the

inspiration of General Rufus Putnam of Rutland (cousin of General

Israel Putnam), organized the Ohio Company which settled Ohio,

beginning at Marietta.

State

Street, when King Street, practically ended at Kilby Street on the

south side and Merchants Row on the north, till the reclamation of

the flats beyond, high-water mark being originally at these points.

“Mackerel Lane” was a narrow passage by the shore till after the

“Great Fire of 1760,” which destroyed much property in the

vicinity. Then it was widened and named Kilby Street in recognition

of the generous aid which the sufferers by the fire had received from

Christopher Kilby, a wealthy Boston merchant, long resident in London

as the agent for the town and colony, but then living in New York.

Nearly

opposite the Bunch-of-Grapes, at about the present No. 66, stood

the British Coffee House, where the British officers

principally resorted. It was here in 1769 that James Otis was

assaulted by John Robinson, one of the royal commissioners of

customs, upon whom the fiery orator had passed some severe

strictures, and thus through a deep cut on his head this brilliant

intellect was shattered.

At

the east corner of Exchange Street was the Royal Customhouse,

where the attack upon its sentinel by the little mob of men and boys,

with a fusillade of street snow and ice, and taunting shouts, led to

the Massacre of 1770. The opposite, or west, corner was

occupied by the Royal Exchange Tavern, dating from the early

eighteenth century, another resort of the British officers stationed

in town. It was here in 1727 that occurred the altercation which

resulted in the First Duel fought in Boston (on the Common),

when Benjamin Woodbridge was killed by Henry Phillips, both young men

well connected with the “gentry” of the town, the latter related

by marriage to Peter Faneuil, the giver of Faneuil Hall. Woodbridge’s

grave is in the Granary Burying Ground, and can be seen close by

the sidewalk fence.

It

was this grave which inspired those tender passages in the “Autocrat

of the Breakfast Table” describing “My First Walk with the

Schoolmistress.”

The

Old State House dates from 1748. Its outer walls, however,

are

older, being those of its predecessor, the second Town and Province

House, built in 1712-1713. That house was destroyed by fire, all but

these walls, in 1747, sharing very nearly the fate of its

predecessor, the first Town House and colonial building, which went

down in the “Great Fire” of 1711 with the second meetinghouse

and

neighboring buildings and dwellings. It occupies the identical site

in the middle of the market, stead chosen for the first Town House in

1657. It has served as Town House, Court House, Province Court House,

State House, and City Hall. As the Province Court House, identified

with the succession of prerevolutionary events in Boston, it has a

special distinction among the historical buildings of the country.

After its abandonment for civic uses it suffered many vicissitudes

and indignities, being ruthlessly refashioned, made over, and patched

for business purposes, that the city which owns it might wrest the

largest possible rentals from it; and in the year 188 its

removal was seriously threatened. Then, through the well-directed

efforts of a number of worthy citizens, its preservation was secured,

and in 1882 the historic structure was restored to much the

appearance which it bore in Provincial days. Further restorations

were made in 1908-1909.

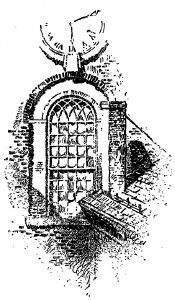

|

In

both exterior and interior the original architecture is in large part

reproduced. The balcony of the second story has the window of twisted

crown glass, out of which have looked all the later royal governors

of the Province and the early governors of the Commonwealth. The

windows of the upper stories are modeled upon the small-paned windows

of Colonial days. Within, the main halls have the same floor and

ceilings, and on three sides the same walls that they had in 1748.

The eastern room on the second floor, with its outlook down State

Street, was the Council Chamber, where the royal governors and the

council sat. The western room was the Court Chamber. Between the two

was the Hall of the Representatives. The King’s arms, which were in

the Council Chamber before the Revolution, were removed by Loyalists

and sent to St. John, New Brunswick, where they now decorate a

church. The carved and gilded arms of the Colony (handiwork of a

Boston artisan, Moses Deshon), displayed above the door of the

Representatives Hall after 1750, disappeared with the Revolution. The

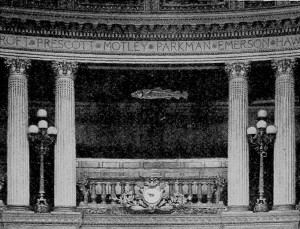

Wooden Codfish, “emblem of the staple of commodities

of the

Colony and the Province,” which hung from the ceiling of this

chamber through much of the Province period, is reproduced in the

more artistic figure (embellished by Walter M. Brackett, the master

painter of fish and game) that now hangs in the Representatives Hall

of the present State House.

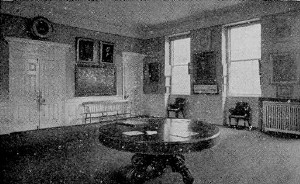

|

Old State House

|

|

The

restored rooms above the basement are open for public exhibition,

with the rare collection of antiquities relating to the early history

of the Colony and Province, as well as the State and the Town,

brought together by the Bostonian Society, to whose control

these rooms passed, through lease by the city, upon the restoration

of the building. The collection embraces a rich variety of

interesting relics: historical manuscripts and papers; quaint

paintings, engravings, and prints; numerous portraits of old

worthies; and many photographs illustrating Boston in various

periods. In the Council Chamber is the old table formerly used by the

royal governors and councillors.

The

Bostonian Society, established here, was incorporated in 1881 “to

promote the study of the history of Boston, and the preservation of

its antiquities”; and in it was merged the Antiquarian Club,

organized in 1879 especially for the promotion of historical

research, whose members had been most influential in the campaign for

the preservation of this building. It has rendered excellent service

in the identification of historic sites and in verifying historical

records.

|

Council Chamber, Old

State House |

|

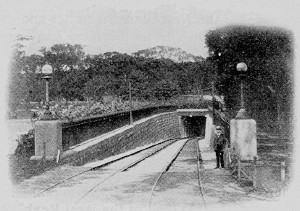

Deep

down below the basement of the building is now the State station of

the Washington Street Tunnel, and also the State Street

station of the East Boston Tunnel, which runs directly under

the ancient structure to Scollay Square, where it connects by

passageways with the Subway.

The

first Town House, completed in 1659, was provided for by the will of

Captain Keayne, the Ancient and Honorable Artillery

Company’s

chief founder (the longest will on record, comprising 158 folio pages

in the testator’s own hand, though disposing of only £4000).

Captain Keayne left £300 for the purpose, and to this sum was

added £100 more, raised by subscription among the townspeople,

and paid largely in provisions, merchandise, and labor. It was a

small “comely building” of wood, set upon twenty pillars,

overhanging the pillars “three feet all around,” and topped by

two tall slender turrets. The place inclosed by the pillars was a

free public market, and an exchange, or “walk for the merchants.”

|

Franklin Press,

Old State House

|

It

contained the beginnings of the first public library in America,

for which provision was made in Captain Keayne’s will. Portions of

this library were saved from the fire of 1711 which destroyed the

building; but these probably perished later in the burning of the

second Town and Province House.

The

second house, of brick, completed in 1713, also had an open public

exchange on the street floor. Surrounding it were thriving

booksellers’ shops, observing which Daniel Neal, visiting the town

in 1719, was moved to remark that “the Knowledge of Letters

flourishes more here than in all the other English plantations put

together; for in the city of New York there is but one book seller’s

shop, and in the Plantations of Virginia, Maryland, Carolina,

Barbadoes, and the Islands, none at all.” So, it appears, thus

early Boston was the “literary center” of the country, a fact

calculated to bring almost as great satisfaction to the complacent

Bostonian as that later-day saying in the “Autocrat” (in which

this stamp of Bostonian declines to recognize any satire), that

“Boston State-House is the hub of the solar system”

Down

State Street. Following State Street to its end, we shall come

upon Long Wharf (originally Boston Pier, dating from 171o), where the

formal landings of the royal governors were made, the main landing

place of the British soldiers when they came, and the departing place

at the Evacuation. At that time it was a long, narrow pier, extending

out beyond the other wharves, the tide ebbing and flowing beneath the

stores that lined it. Atlantic Avenue, the water-front thoroughfare

that now crosses it, and on which the elevated railway runs, follows

generally the line of the ancient Barricado, an early harbor

defense erected in 1673 between the north and south outer points of

the “Great Cove.” It connected the North Battery, where is

now Battery Wharf, and the South Battery, or “Boston

Sconce,” at the present Rowe’s Wharf, where the steamer for

Nantasket is taken. It was provided with openings to allow vessels to

pass inside, and so came to be generally called the “Out Wharves.”

Its line is so designated on the early maps.

|

In

the short walk down State Street are passed in succession on either

side of the way notable modern structures that have almost entirely

replaced the varied architecture of different periods, which before

gave this street a peculiar distinction and a certain picturesque

ness that is now wanting. The Exchange Building takes the

place of the first Merchants’ Exchange, a dignified building in its

day (1842 1890), covering a very small part of the ground over which

the present structure spreads. The Board of Trade Building, at

the east corner of Broad Street, is, perhaps, the most attractive in

design of the newer architecture. At the India Street corner, its

massive granite-pillared front facing that street, is the United

States Custom House (dating from 1847), in marked contrast

with its younger neighbors. This occupied several years in building,

and the transportation of the heavy granite columns, each weighing

about forty-two tons, which surround it on all sides, was a great

feat for the time. Its site was the head of Long Wharf, and the

bowsprits of vessels lying there, stretching across the street,

almost touched its eastern side.

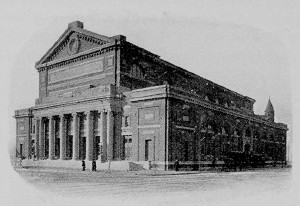

|

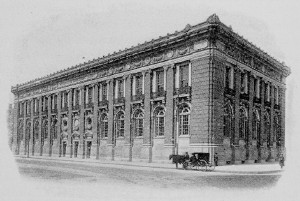

Custom House |

On

India Street, a few rods south of this specimen of a past

architecture, is the modern Chamber of Commerce (built in

1902), also of granite. Viewed from a distance, its rounded front,

with turreted dormer windows and conical tower, has a unique

appearance. Opposite it opens Custom House Street, only a block in

length, where is still standing the Old Custom House, built in

1810, in which Bancroft, the historian, served as collector of the

port in 1838-1841, and which was the “darksome dungeon” where

Hawthorne spent his two years as a customs officer, first as a

measurer of salt and coal, then as a weigher and gauger.

Faneuil

Hall and its Neighborhood. From lower State Street we can pass to

Faneuil Hall by way of Commercial Street and the long granite Quincy

Market House, — the central piece of the great work of the

first Mayor Josiah Quincy, in 1825-1826, in the construction of six

new streets over a sweep of flats and docks, — or we may go direct

from the Old State House through Exchange Street, a walk of a few

minutes.

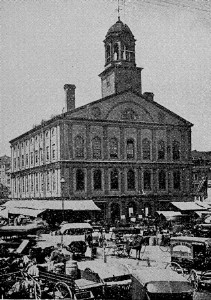

Faneuil

Hall as now seen is the “Cradle of Liberty” of the

Revolutionary period doubled in width and a story higher. The

enlargement was made in 1805, under the superintendence of Charles

Bulfinch, the pioneer Boston architect of enduring fame, whose most

characteristic work we shall see in the “Bulfinch Front “of the

present State House, The hall was built in 1762-1763, upon the brick

walls of the first Faneuil Hall, Peter Faneuil’s gift to the town

in 1742, which was consumed, except its walls, in a fire in January,

1762. Bulfinch, in his work of 1805, introduced the galleries resting

on Doric columns, and the platform with its extended front, with

various interior embellishments. In 1898 the entire building was

reconstructed with fireproof material on the Bulfinch plan, iron,

steel, and stone being substituted for wood and combustible

material

Faneuil Hall

|

Of

the fine collection of portraits on the walls many are copies, the

originals having been placed in the Museum of Fine Arts for

safe-keeping. The great historical painting at the back of the

platform, “Webster’s Reply to Hayne,” by G. P. A. Healy,

contains one hundred and thirty portraits of senators and other men

of distinction at that time. The scene is the old Senate Chamber, now

the apartment of the United States Supreme Court. The canvas measures

sixteen by thirty feet. The portrait of Peter Faneuil, on one side of

this painting, is a copy by Colonel Henry Sargent, from a smaller

portrait in the Art Museum, and was given to the city by Samuel

Parkman, grandfather of the historian Parkman. It takes the place of

a full-length portrait executed by order of the town in 1744, as a

“testimony of respect” to the donor of the hall, which

disappeared, and was probably destroyed, at the siege of Boston, —

the fate also of portraits of George H, Colonel Isaac Barré,

and Field Marshal Conway, the last two solicited by the town in

gratitude for their defense of Americans on the floor of Parliament.

The full-length Washington, on the other side of the great painting,

is a Gilbert Stuart. It, also, was presented to the town by Samuel

Parkman, in 1806. Of the portraits elsewhere hung, those of Warren,

Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Quincy Adams are all

Copleys. The General Harry Knox and the Commodore Preble are credited

to Stuart. The Abraham Lincoln and Rufus Choate are by Ames. The “war

governor,” John A. Andrew, is by William M. Hunt. The others —

Robert Treat Paine, Caleb Strong, Edward Everett, Admiral Winslow,

Wendell Phillips, and Anson Burlingame — are by various American

painters. The ornamental clock in the face of the gallery over the

main entrance was a gift of Boston school children in 1850. The

gilded spread eagle was originally on the façade of the United

States Bank which, erected in 1798, preceded the first Merchants’

Exchange on State Street. The gilded grass hopper on the cupola of

the building, serving as a weather vane, is the reconstructed, or

rejuvenated, original one of 1742, fashioned from sheet copper by the

“cunning artificer,” “Deacon” Shem Drowne, immortalized by

Hawthorne in “Drowne’s Wooden Image.”

|

The

floors above the public hall have been occupied by the Ancient and

Honorable Artillery Company for many years. Its armory is a rich

museum of relics of Colonial, Provincial, and Revolutionary times,

and is hospitably open to appreciative inspection. Among the

treasured memorials here are the various banners of the company, the

oldest being that carried in 1663. Eighteen silk flags reproduce

colonial colors and their various successors. In the London room are

mementos of the visit of a section of the company to England in the

summer of 1896, as guests of the Honourable Artillery Company of

London. On the walls of the main hall are portraits of one hundred

and fourteen captains of the company. On the street floor of the

building is the market, which has continued from its establishment

with the first Faneuil Hall in 1742. John Smibert, the Scotch

painter, long resident and celebrated in Boston from 1729, was the

architect of the first building.

Faneuil

Hall was instituted primarily as a market house, the inclusion of a

public town hall in the scheme being an afterthought of the donor.

Peter Faneuil’s offer to provide a suitable building at his own

expense upon condition only that the town should legalize and

maintain it, was at a time of controversy over the town market houses

then existing. Three had been set up seven years before, one close to

this site, in Dock Square; one at the North End, in North Square; the

third at the then South End, by the south corner of the present

Boylston and Washington streets. The Dock Square market was the

principal one, and this had recently been demolished by a mob

“disguised as clergymen.” The contention was over the market

system. One faction demanded a return to the method of service at the

home of the townspeople, as before the setting up of these market

houses; the others insisted upon the fixed market-house system. So

high did the feeling run that Faneuil’s gift was accepted by the

town by the narrow margin of seven votes.

The

building was completed in September, 1742. It was only one hundred

feet in length and forty feet wide. But it was of brick, and

substantial. The hall, calculated to hold only one thousand persons,

was pronounced in the vote of the first town meeting held in it as

“spacious and beautiful.” In the same vote it was named Faneuil

Hall, “to be at all times hereafter called and known by that name,”

in testimony of the town’s gratitude to its giver and to perpetuate

his memory. Then his full-length portrait was ordered for the hall;

and a year and a half later the Faneuil arms, “elegantly carved and

gilt” by Moses Deshon, the same who later carved the Colony seal

for the Town House, were added at the town’s expense.

The

first public gathering in the hall, other than a town meeting, was,

singularly, to commemorate Faneuil, he having died suddenly, March 3,

1743, but a few months after the completion of the building. On this

occasion the eulogist was John Lovell, master of the Latin School,

who in the subsequent prerevolutionary controversies was a Loyalist,

and at the Evacuation went off to Halifax. The Faneuils who succeeded

Peter, his nephews, were also Loyalists, and left the country with

the Evacuation.

The

second Faneuil Hall, embraced in the present structure, was built by

the town, and the building fund was largely obtained through a

lottery authorized by the General Court. The first public meeting in

this hall was on March 14, 1763, when the patriot James Otis was the

orator, and by him the hall was dedicated to the “Cause of

Liberty.” Then followed those town meetings of the Revolutionary

period, debating the question of “justifiable resistance,” from

which the hall derived its sobriquet of the “Cradle of American

Liberty.” In 1766 cm the news of the Stamp Act repeal the hall was

illuminated. In 1768 one of the British regiments was quartered here

for some weeks. In 1772 the Boston Committee of Correspondence, “to

state the rights of the colonists” to the world, was established

here, on that motion of Samuel Adams which Bancroft says “contained

the whole Revolution.” In 1773 the “Little Senate,” composed of

the committees of the several towns, began their conferences with the

“ever-vigilant” Boston committee, in the selectmen’s room.

During the siege the hall was transformed into a playhouse, under the

patronage of a society of British officers and Tory ladies, when

soldiers were the actors, and a local farce, “The Blockade of

Boston,” by General Burgoyne, was the chief attraction.

Since

the Revolution the hall has been the popular meeting place of

citizens on important and grave occasions, and a host of national

leaders, orators, and agitators have spoken from its historic

rostrum. In 1826 Webster delivered here his memorable eulogy on Adams

and Jefferson, in the presence of President John Quincy Adams and an

audience of exceptional character. Here in 1837 Wendell Phillips made

his first antislavery speech; in 1845 Charles Sumner first publicly

appeared in this cause; in 1846 the antislavery Vigilance Committee

was formed at a meeting to denounce the return of a fugitive slave;

in 1854 the preconcerted signal was given, at a crowded meeting to

protest against the rendition of Anthony Burns, for the bold but

fruitless move on the Court House (see p. 59) to effect the escape of

this fugitive slave.

|

Faneuil

Hall is protected by a provision of the city charter forbidding its

sale or lease. It is never let for money, but is opened to the people

upon the request of a certain number of citizens, who must agree to

comply with the prescribed regulations.

Faneuil

Hall occupies made land close to the head of the Old Town Dock. The

streets around the sides and back of the building constitute Faneuil

Hall Square. From the south side of this square opens Corn Court,

which runs in irregular form to Merchants Row. This space was the

Corn Market of Colonial times. A landmark of a later day here, which

remained till 1903, was an old inn long known as Hancock Tavern.

While not so ancient as it was assumed to be, nor occupying, as

alleged, the site of the first tavern in the town, it was an

interesting landmark with rich associations. It became the Hancock

Tavern when John Hancock was made the first governor of the

Commonwealth, and the swing sign displaying his roughly painted

portrait is still preserved. At other periods it was the Brazier Inn,

kept by Madam Brazier, niece of Provincial Lieutenant Governor

Spencer Phipps (1733), who made a specialty of a noonday punch for

its patrons. In this tavern lodged Talleyrand, when exiled from

France, during his stay in Boston in 1795; also, two years later,

Louis Philippe; and, in 1796, the exiled French priest, John

Cheverus, who afterward became the first Roman Catholic bishop of

Boston. An annex to a modern office building occupies its site.

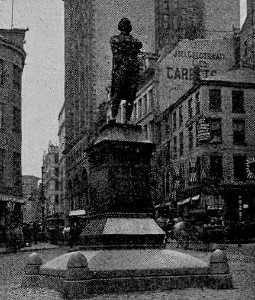

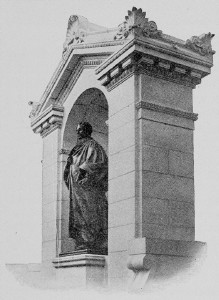

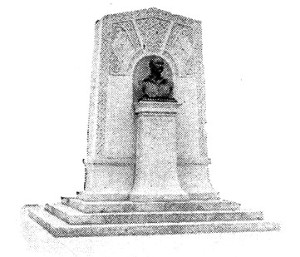

|

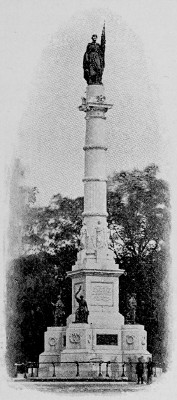

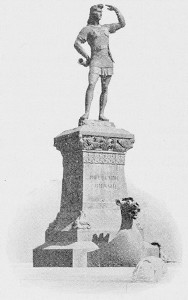

The Adams Statue |

East

of Corn Court, near the east end of Faneuil Hall, also on land

reclaimed from the Town Dock, was John Hancock’s Store,

where he advertised for sale “English and India goods, also choice

Newcastle Coals and Irish Butter, Cheap for Cash.” West of Corn

Court opens Change Alley (incongruously designated as

“avenue”), a quaint, narrow foot passage to State Street, one of

the earliest ways established in the town. It was sometime Flagg

Alley, from being laid out with flag stones. Until the erection of

the great financial buildings that now largely wall it in, the alley

was picturesque with bustling little shops.

On

the west side of Faneuil Hall Square the triangle, covered with low,

old buildings, marks the head of the ancient Town Dock.

Old

Dock Square makes into modern Adams Square (opened

in

1879), near the middle of which stands the bronze statue of Samuel

Adams, by Anne Whitney. This is a counterpart of the statue of

the revolutionary leader in the Capitol at Washington. It portrays

him as he is supposed to have appeared when before Lieutenant

Governor Hutchinson and the council, in the Council Chamber of the

Old State House, as chairman of the committee of the town meeting the

day after the Boston Massacre of 1770, and at the moment that,

having delivered the people’s demand for the instant removal of the

British soldiers from the town, he stood with a resolute look

awaiting Hutchinson’s reply.

The

principal architectural feature of this open space is the stone Adams

Square Station of the Subway.

Cornhill

and about Scollay Square. From the west side of Adams Square we

pass into Cornhill, early in its day a place of bookshops, and still

occupied by several booksellers at long-established stands. It is the

second Cornhill, the first having been the part of the present

Washington Street between old Dock Square and School Street.

Washington Street originally ended at Dock Square north of the

present Cornhill, and its extension to Haymarket Square (1872), where

it now ends, greatly changed this part of the town and obliterated

various landmarks. A little north of the present opening of Cornhill,

lost in the Washington Street extension, was the site of the dwelling

of Benjamin Edes, where, on the afternoon preceding the Boston Tea

Party of December 16, 1773, a number of the leaders in that

affair met and partook of punch from the punch bowl now possessed by

the Massachusetts Historical Society.

This

Cornhill dates from 1816, and was first called Cheapside, after the

London fashion. Then for a while it was Market Street, being a new

way to Faneuil Hall Market. From its northerly side was once an

archway leading to Brattle Street and old Dock Square, which also

disappeared in the extension of Washington Street. Midway, at

its curve toward Court Street, where it ends, it is crossed by

Franklin Avenue (another short passageway, or alley, with

this

ambitious title), at the Court Street end of which was Edes &

Gill’s printing office, the principal rendezvous of the

Tea-Party men, in a back room of which a number of them assumed

their disguise. This was on the westerly corner of the “avenue,”

then Dasset Alley, and Court, then Queen, Street. Earlier, on the

east corner, was the printing office of Benjamin Franklin’s brother

James, where the boy Franklin learned the printer’s trade as

his brother’s apprentice, and composed those ballads on “The

Lighthouse Tragedy” and on “Teach” (or “Blackbeard”), the

pirate, which he peddled about the streets with a success that

“flattered” his “vanity,” though they were “wretched

stuff,” as he confesses in his Autobiography. Here James Franklin

issued his New England Courant, the fourth newspaper that

appeared in America, which Franklin managed during the month in which

his brother was imprisoned for printing an article offensive to the

Assembly, and himself “made bold to give our rulers some rubs in

it”; and which, after James’s release inhibited from publishing,

was issued for a while under Benjamin’s name.

The

north end of Franklin Avenue, from Cornhill by a short flight of

steps, is at Brattle Street, a short distance above the site

of Murray’s Barracks, on the opposite side, where were

quartered the Twenty, Ninth, the regiment of the British force of

1768-1770 most obnoxious to the “Bostoneers,” and where the

fracas began that culminated in the Boston Massacre. The

Quincy House, nearer the avenue’s end, covers the site of the first

Quaker meetinghouse, built in 1697, the first brick meetinghouse

in the town. Opposite the side of the Quincy House, facing Brattle

Square, stood till 1871 the Brattle Square Church, which

after the Revolution bore on its front a memento of the Siege, in the

shape of a cannon ball, thrown there by an American battery at

Cambridge on the night of the Evacuation. This was the meetinghouse

alluded to in Holmes’s “A Rhymed Lesson,”

. .. that, mindful of the hour

When Howe’s artillery shook its

half-built tower,

Wears on its bosom, as a bride

might

do,

The iron breastpin which the ‘Rebels’

threw.

A

model of the church as it thus appeared is in the house of the

Massachusetts Historical Society, where also the cannon ball is

preserved. The quoins of the structure, of Connecticut stone, were

placed inside the tower of its successor on Commonwealth Avenue, Back

Bay, now the church of the First Baptist Society. Though new, and

“the pride of the town “at the time of the Revolution, having

been consecrated in 1773, it was utilized as barracks for the British

soldiers; and only the fact that the removal of the pillars which

embellished its interior would have endangered the structure,

prevented its use during the Siege as a military riding school, like

the Old South Meetinghouse (see p. 51). It was the church that

Hancock, Bowdoin, and Warren attended. Warren’s house, from

1764, was near by on Hanover Street, on the site now covered by the

American House.

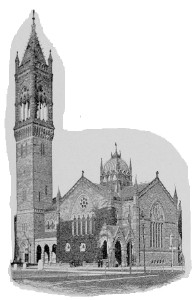

Court Street |

At

the head of Cornhill, in front of Scollay Square, stood the

bronze statue of John Winthrop until its removal was

necessitated by the East Boston Tunnel work below it in 1903. It was

well worth a moment’s study, though the constant traffic of the

busy thoroughfare made its near neighborhood perilous. The Colonial

governor, clad in the picturesque costume of the period, is

represented as stepping from a gang board to the shore. In his right

hand he holds the charter of the Colony by its great seal; in his

left the Bible. Behind the figure appears the base of a newly hewn

forest tree, with a rope attached, significant of the fastening of a

boat. The statue is the work of Richard S. Greenough and is a copy of

the marble one in the Capitol at Washington. It was cast in Rome. It

was first erected in 1880, on the 250th anniversary of the settlement

of Boston. It now stands on Marlborough Street beside the First

Church.

About

where the Scollay Square Station stands, or a little north of its

site, was the first Free Writing School, set up in 1683-1684.

This was the second school in the town, the first being on School

Street, as we shall presently see. It continued in use till after the

Revolution (or about 1793), latterly known as the Central Reading and

Writing School.

Looking

down Court Street eastward, we have in near view the

somber-pillared front of the Old Court House, dating from 1836. It

was designed by Solomon Willard, the architect of Bunker Hill

Monument. Its exterior is of Quincy granite. The ponderous fluted

columns (originally eight in all, there having been a row on the rear

as well as in front) weigh each twenty-five tons. The first two were

brought over the roads from Quincy by sixty-five yoke of oxen and ten

horses, making a great street show. This building was the center of

the exciting scenes attending the fugitive slave cases in 1851 and

1854. Here is the main entrance to the East Boston Tunnel.

|

Here

occurred first, in February, 1851, the rescue of Shadrach, who had

been confined in the United States court room awaiting action upon a

process for his rendition. Six weeks later came the Thomas Sims

affair, when, to prevent the rescue of this slave, the building was

guarded and surrounded with chains breast high, under which the

judges and all others having business within were obliged to stoop to

reach the doors. Finally, in May, 1854, occurred the Anthony Burns

riot, on the evening of the 26th, with the failure of the rescue

planned by a number of the anti slavery “Vigilance Committee,”

when, in the assault made at the entrance on the west side of the

building, one of the marshal’s deputies was killed. It was after

this affair that indictments were brought against Theodore Parker,

Wendell Phillips, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and several others, for

“obstructing the process of the United States.” For their defense

a formidable array of counsel appeared here, but the indictment was

quashed.

|

On

this same spot was the Colonial prison, its outer walls of

stone three feet thick, with unglazed iron-barred windows, stout

oaken doors covered with iron, hard cells, and gloomy passages, where

were incarcerated the Quakers and, later, victims of the witchcraft

delusion. Here also, after the overthrow of Andros in 1689,

Ratcliffe, the rector of the first Episcopal church, which Andros so

fostered (see King’s Chapel, p. 24), was confined with his leading

parishioners for nine months, till sent to England by royal command.

Another distinguished prisoner here, in 1699, was the piratical

Captain Kidd. It was this prison that Hawthorne fancifully describes

in “The Scarlet Letter.” The prison was first placed here in

1642, and gave to the street the name of Prison Lane, which it

bore through the seventeenth century. Then it became Queen Street,

and Court Street after the Revolution.

Looking

westward up Court Street to the upper side, called Tremont

Row, we may imagine the site of Governor John Endicott’s

house, where he lived after his removal from Salem to Boston, and

where, in 1661, Samuel Shattuck, bearing the order of the King

releasing the imprisoned Quakers, had audience with him, — the

event upon which Whittier’s “The King’s Missive” is founded.

This house is variously placed by local authorities on Tremont Row,

between Tremont Street and Howard Street, but the best evidence

appears to point to a situation toward the Howard Street end.

|

The Winthrop Statue

|

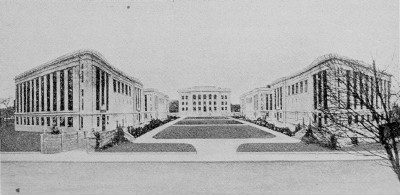

Tremont

Street and King’s Chapel. Now we take Tremont Street. From the

west side, at its beginning, opens the short way up to Pemberton

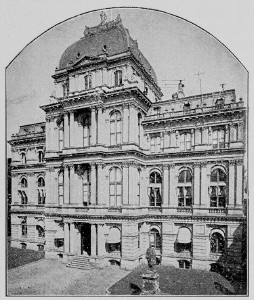

Square, at the head of which we see the façade of the

present County Court House (built 1887-1893). This is a long

granite structure in the German Renaissance style of architecture,

designed by George A. Clough. Its plan is on the system of open

courtyards: four are in the area of the general block. It covers

65,300 feet of land. The feature of the interior is the great hall,

broad and lofty, a flight of steps ascend ing to it from the front

entrance, and other flights ascending from it to the rear exit on

Somerset Street. Upon the faces of the cornices in the

vestibule at the main entrance are statuesque bas-reliefs of Law,

Justice, Wisdom, Innocence, and Guilt. On one side of the hall is the

bronze statue of Rufus Choate, the great lawyer of his day.

This is by Daniel C. French. It was placed in 1898. It was a gift to

the city, provided for in the will of a Boston public-school master.

The donor was some time master of the Dwight School for boys, and

afterward principal of the Everett School for girls.

Pemberton

Square marks the second highest peak of Beacon Hill. This

peak at first received the name of Cotton Hill, from the Rev.

John Cotton, the early minister of the First Church, whose house was

on its slope facing Tremont Street. The Cotton estate

originally spread over this peak, extending back across Somerset

Street to about the middle of Ashburton Place in the rear of the

Court House.

The

peak rose originally in irregular heights, the loftiest bluff being

at the southerly end of Pemberton Square, or on the west side of

Tremont Street about opposite the gate of King’s Chapel Burying

Ground. Against its slopes were early favorite places for house

sites.

John

Cotton’s house was set up in 1633, soon after his arrival in

the Griffin. It stood a little south of the entrance to

Pemberton Square. Next above, or adjoining it, was Sir Harry

Vane’s house. This was built by the young statesman a few

months after his arrival (October, 1635), he having at first been the

minister’s guest. It was Vane’s home when he was governor of the

Colony in 1636-1637. Later the Cotton house came into possession of

John Hull, the “mint master,” who made the pine-tree

shillings, the first New England money. In course of time it fell to

Chief Justice Samuel Sewall (one of the witchcraft judges

at

Salem in 1692), the diarist of early Boston, through his marriage

with the “mint master’s” daughter Hannah, whose wedding dowry,

tradition tells, was her weight in the pine-tree shillings.

|

About

on the site now occupied by the showy Beacon Theater, but back from

the street, was Richard Bellingham’s stone house, in which

he lived through his several terms as governor and till his death in

1672. He was dwelling here when, in 1641, he scandalized his brethren

by the manner of his marriage to Penelope Pelham, his second wife,

without “publishing” the marriage intention, and especially by

performing the marriage ceremony himself, being a magistrate, as

Winthrop relates in picturesque detail in his journal.

In

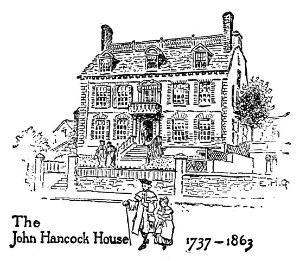

the next century the grand Faneuil mansion and terraced

gardens were here. This was the estate that Peter Faneuil inherited

in 1737 and was occupying when he built Faneuil Hall. It was

maintained in all its elegance by its several owners till some years

after the Revolution. At that time it was confiscated, its owner

being a Royalist, — William Vassal, uncle of the Colonel

John Vassal who built the Cambridge mansion now treasured as the

Longfellow house. Early in the nineteenth century it was joined to

the Gardner Greene estate, the finest in the town.

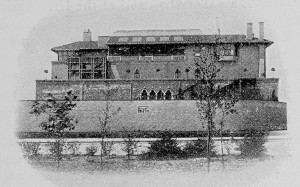

|

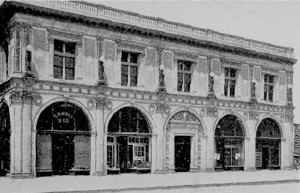

Old

Boston Museum

|

The

peak was finally cut down in the thirties, and Pemberton Square was

then laid out through the Greene estate as a place of genteel

residences in blocks, which character it sustained till the late

sixties.

On

the east side the Boston Museum, razed in 1903 to make way for

a modem business structure, long stood the oldest playhouse of the

city. For more than half a century it was a familiar landmark. At

first the museum proper, with its halls of marvelous curiosities, was

the chief feature of the institution, the performances being

subordinate to these attractions, and the theater being called “the

lecture hall,” to quiet the consciences of its patrons, who shied

from the openly pro claimed playhouse. William Warren, the “prince

of comedians,” as Bostonians delighted in calling him, was

identified with the Museum for forty years. Here Edwin Booth made his

first appearance on any stage.

From

King’s Chapel to Park Street Church. King’s Chapel Burying

Ground, adjoining the old stone church, is very nearly as ancient as

the town of Boston. The exact date of its establishment is not known,

but it was probably soon after the beginning of the settlement, for

this record appears in Winthrop’s journal: “Capt. Welden, a

hopeful young gent, & an experienced soldier, dyed at

Charlestowne of a consumption, and was buryed at Boston wth a

military funeral.” And Dudley wrote that the young man was “buryed

as a souldier with three volleys of shott.” The earliest interment

of record here was that of Governor Winthrop in 1649. It is believed

that his third wife, Margaret Winthrop, who followed him to New

England the year after he came out and who died two years before him,

was also buried here.

In

the same tomb are the ashes of other distinguished Winthrops — the

Massachusetts governor’s eldest son and grandsons: John Winthrop,

Jr., the governor of the Connecticut Colony, who died in 1676, and

John Jr.’s two sons, Fitz John Winthrop, governor of the United

Colonies of Connecticut (died 1707), and Wait Still Winthrop, chief

justice of Massachusetts and sometime major general of the forces of

the Colony (died 1717). A second Winthrop tomb contains the dust of

Professor John Winthrop of Harvard College, the friend of Franklin

and correspondent of John Adams (died in 1779).

The

first Winthrop tomb is seen not far from the middle of the ground.

Beside it is the tomb of Elder Thomas Oliver of the First Church,

which subsequently became the property of the church; and close to

this a horizontal tablet informs that “here lyes intombed the

bodyes of ye famous reverend and learned pastors of the First Church

of Christ in Boston, viz:” John Cotton, aged 67 years, died 1652;

John Davenport, 72 years, died 1670; John Oxenbridge, aged 66 years,

died 1674; and Thomas Bridge, aged 58 years, died 1715. Near by are

the modest gravestones of Sarah, “the widow of the beloved John

Cotton and excellent Richard Mather,” and of Elizabeth, widow of

John Davenport.

In

the middle of the ground is the marble monument to Colonel Thomas

Dawes, a leading Boston mechanic of his day, who died in 1809, and

near it the tomb of Governor John Leverett. A few steps distant is

that of the Boston branch of the Plymouth Colony Winslow family. Here

are the ashes of John Winslow, brother of Governor Edward Winslow,

with those of the former’s wife, who was Mary Chilton, one of the

Mayflower passengers, heroine of the popular but

apocryphal

tale of the first woman to spring ashore from the Pilgrim ship. In a

cluster of ancient tombs are those of Jacob Sheafe, an opulent

merchant of Colony times, in which was afterward buried the Rev.

Thomas Thacher, first pastor of the Old South Church (died 1678), who

married Sheafe’s widow; and of Thomas Brattle (died 1683), said

probably to have been the wealthiest merchant of his day, whose son

Thomas became a treasurer and benefactor of Harvard College. A tomb

of especial interest in this quarter is the Benjamin Church tomb, for

herein were deposited the remains of Lady Andros, the wife of

Governor Andros, who died in February, 1688, and of whose funeral in

the nighttime from the Old South Meetinghouse Sewall gives a quaint

account in his diary. Other tombs of note are those of Major Thomas

Savage, one of the commanders in King Philip’s War, and Judge

Oliver Wendell, grandfather of Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Many

of the old tombstones here have been shifted from their proper places

and made to serve as edge stones along the paths beyond the principal

gateway. This vandalism was the performance years ago of a

superintendent of burials who was possessed with an evil “eye for

symmetry.”

King’s

Chapel in part occupies the upper end of this burying ground,

which extended originally to School Street, the land having been

taken by Governor Andros in 1688 for the first Episcopal church, no

Puritan landholder being found who would sell for such a purpose.

This building dates from 1754 and is the second King’s Chapel on

the spot. Its aspect has been little changed, beyond the enrichment

of the interior, from Province days. The low solid edifice of dark

stone, with its heavy square tower surrounded by wooden Ionic

columns, stands as it appeared when it was the official church of the

royal governors. The stone of which it is constructed came from

Quincy (then Braintree), where it was taken from the surface, there

being then no quarries. It was built so as to inclose the first

chapel, in which services were held for the greater part of the time

consumed in the slow work, — about five years. Peter Harrison, an

Englishman who came out in 1729 in the train of Dean Berkeley to have

part in the dean’s projected but never established university, was

the architect. His model was the familiar English church of the

eighteenth century; so the visitor sees in the fashion of the

interior, its rows of columns supporting the ceiling, the antique

pulpit and reading desk, the mural tablets and the sculptured

monuments that line the walls, a pleasant likeness to an old London

church. Memorials of the first chapel are preserved in the chancel.

The communion table of 1688 is still in use. Several of the mural

tablets are of the Provincial period. On the organ are in their

ancient places the gilt miters and crown, which were removed at the

Revolution and deposited in a place of safety. Among the tablets on

the northern wall is one to the memory of Oliver Wendell Holmes. This

was placed in the autumn of 1895. The inscription was composed by

ex-President Eliot of Harvard University.

|

King's Chapel |

At

the Evacuation the venerable rector, Mr. Caner, fled with the

Loyalists of his parish, taking off with him to Halifax the church

registers, plate, and vestments, but most of these were in later

years restored.

The

last Loyalist service before the Evacuation was on the preceding

Sunday. In less than a month after the Evacuation the chapel was

reopened for the obsequies of General Joseph Warren, who fell at

Bunker Hill, and on that occasion the orator, Perez Morton, advocated

independence. For more than two years thereafter the chapel was

closed. Then it was opened to the Old South congregation, and it was

used by the latter for nearly five years, when their meetinghouse

was restored. In 1782 the remnant of the society renewed their

services with the Rev. James Freeman as “reader.” In 1787 Mr.

Freeman was ordained as rector, and at that time this first Episcopal

church in New England became the first Unitarian church in America. A

bust of Mr. Freeman is among the mural monuments.

|

The

original King’s Chapel of 1688 was a small wooden structure, built

at a cost of £284 16 s, contributed by persons throughout the

Colony, with subscriptions from Andros and other English officers.

For more than two years before its erection the Episcopal

congregation had joint occupancy of the Old South Church with its

proper owners, by order of Governor Andros against their earnest and

constant protest. The church organization was formed in 1686, under

the aggressive leadership of Edward Randolph, with the Rev. Robert

Ratcliffe as rector, who had come from England commissioned to

establish the Church of England in the Colony. The use of any of the

Congregational meetinghouses being denied them, the projectors of the

church founded it in the “library room” of the Town House. This

was their place of meeting till Andros ordered the Old South opened

to them. When Andros was overthrown the rector and his leading

parishioners were imprisoned till their return to England (see p.

19). The remnant of the congregation resumed services in the chapel,

which was finished a few months after Andros’s departure.

In

1710 the chapel was enlarged to twice its size. Then the exterior was

embellished with a tower surmounted by a tall mast half-way up which

was a large gilt crown and at the top a weathercock. Within the

enlarged chapel the governor’s pew, raised on a dais higher by two

steps than the others, hung with crimson curtains and surmounted by

the royal crown, was opposite the pulpit, which itself stood on the

north side at about the center. Near the governor’s pew was another

reserved for officers of the British army and navy. Displayed along

the walls and suspended from the pillars were the escutcheons and

coats of arms of the king, Sir Edmund Andros, Governors Dudley,

Shute, Burnet, Belcher, and Shirley, and other persons of

distinction. At the east end was “the altar piece, whereon was the

Glory painted, the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed,

and some texts of Scripture.” The communion plate was a royal gift.

Less

than a block beyond King’s Chapel, on the opposite side of Tremont

Street, we come to the Granary Burying Ground, established only about

thirty years after the Chapel Burying Ground (in 1660), and of

greater historic interest, perhaps, because of the more numerous

memorials here.

On

the short walk from the Chapel we pass the site of the birthplace

of Edward E. Hale, covered by the upper part of the Parker House.

This hotel also covers, on its School Street side, the site of the

home of Oliver Wendell, the maternal grandfather of Oliver

Wendell Holmes, for whom he was named. On Bosworth Street, the first

passage opening from Tremont Street, opposite the burying ground, —

a courtlike street end ing with stone steps which lead down to a more

ancient cross street, — was Doctor Holmes’s home for

eighteen years from 1841, the “house at the left hand next the

farther corner,” which he describes in “The Autocrat.”

The

Tremont Temple, next above the Parker House, is the

building

of the Union Temple (Baptist) Church, founded in 1839, a free church

from its beginning. It is the fourth temple on this site, each of the

previous ones having been destroyed by fire. The first one was a

theater remodeled in 1843. The playhouse was the Tremont Theater,

first opened in 1835, one of the most interesting of its class and

time.

It

was here that Charlotte Cushman made her début, in April,

1835; that Fanny Kemble first appeared before a Boston audience; that

operas were first produced in Boston.

In

the large public hall of the second Tremont Temple Charles Dickens

gave his readings during his last visit to America, in 1868.

|

The

large Tremont Building opposite occupies the site of the

Tremont House, a famous inn through its career of more than sixty

years from 1829, of which Dickens wrote, “it has more galleries,

colonnades, piazzas, and passages than I can remember, or the reader

would believe.” Preceding the inn, fine mansion houses with gardens

were here, one of them being the estate of Thomas Handasyd

Perkins, a genuine “solid man of Boston,” a benefactor of the

Boston Athenæum and of other Boston institutions.

On

the gates of the Granary Burying Ground, set in their high

ivy-mantled stone frame, are tablets inscribed with the names of many

of the notables buried here. They include governors of various

periods, — Richard Bellingham, William Dummer, James Bowdoin,

Increase Sumner, James Sullivan, and Christopher Gore; signers of the

Declaration of Independence, — John Hancock,

Samuel Adams, and Robert Treat Paine; ministers, — John Baily (of

the First Church), Samuel Willard (of the Old South Church), Jeremy

Belknap (founder of the Massachusetts Historical Society), and John

Lathrop (of the Second Church); Chief Justice Samuel Sewall; Peter

Faneuil; Paul Revere; Josiah Franklin and wife, parents of Benjamin

Franklin Thomas Cushing, lieutenant governor, 1780-1788; John

Phillips, first mayor of Boston, and father of Wendell Phillips;

and the victims of the Boston Massacre of 1770.

|

|

Besides

these, others of like distinction are entombed here, among them James

Otis; the Rev. Thomas Prince, the learned annalist; the Rev. Pierre

Daillé, minister of the French church formed by the Huguenots

who came to Boston after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes;

Edward Rawson, secretary of the Colony; Josiah Willard, secretary of

the Province; and John Hull, the “mint master” of 1652. General

Joseph Warren’s tomb was here (the Minot tomb, adjoining that of

Hancock) from after the obsequies in King’s Chapel in 1776 till

1825. Then his remains were removed to the Warren tomb under St.

Paul’s Church. In 1855 they were again removed, being finally

deposited in the family vault in Forest Hills Cemetery, Roxbury

District. Wendell Phillips (died 1884) was also temporarily buried

here, beside the tomb of his father, at the right of the entrance

gate. After the death of his widow, two years later, his remains were

removed to Milton and placed by her side.

The

most conspicuous monuments here, all in view from the side walk, are

the bowlders marking the tombs of Samuel Adams and James Otis, the

former near the fence, north of the entrance gate, the latter, also

near the fence, south of the gate; the monument to Benjamin

Franklin’s parents, in the middle of the yard; and the John Hancock

monument, in the southwestern corner. The inscriptions on the Adams

and Otis bowlders give these records:

|

Granary Burying Ground

|

Here

lies buried

Samuel

Adams

Signer

of the Declaration of Independence

Governor

of this Commonwealth

A

leader of men and an ardent patriot

Born

1722 Died 1803

Here

lies buried

James

Otis

Orator

and Patriot of the Revolution

Famous

for his argument

against

Writs of Assistance

Born

1725 Died 1783

|

|

Adams’s

grave is in the Checkley tomb, which adjoins the sidewalk; Otis’s

is in the Cunningham tomb, bearing now the name of George Longley.

The bowlders were placed by the Massachusetts Society of the Sons of

the Revolution in 1898, as the inscriptions show.

The

epitaph on the Franklin monument was composed by Franklin, and first

appeared on a marble stone which he caused to be placed here. The

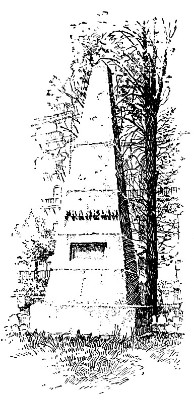

granite obelisk was provided by a number of citizens in 1827, when

the stone had become decayed, and the inscription was reproduced on

the bronze tablet set in its face:

|

Josiah

Franklin

and

Abiah

his wife,

lie

here interred.

They

lived lovingly together in wedlock

fifty-five

years.

Without

any estate, or any gainful employment,

By

constant labor and industry,

with

God’s blessing,

They

maintained a large family

comfortably,

and

brought up thirteen children

and

seven grandchildren

reputably.

From

this instance, reader,

Be

encouraged to diligence in thy calling

And

distrust not Providence.

He

was a pious and prudent man;

She,

a discreet and virtuous woman.

Their

youngest son,

In

filial regard to their memory

Places

this stone

J.

F. born 1655, died 1744, Ætat 89.

A.

F. born 1667, died 1752, — 85.

|

The

Hancock monument is a steel shaft, erected in 1895 close by the

Hancock tomb, set against the wall of one of the buildings which back

on the yard. It is simply inscribed:

Obsta

Principiis

This

memorial erected

A.D.

MDCCCXCV. By the Com

monwealth

of Massachv,

setts

to mark the grave of

John

Hancock.

Near

by the Hancock tomb is a dilapidated slate slab with the inscription,

“Frank, servant of John Hancock Esq’r, lies interred here, who

died 23d Jan’ry 1771, ætat 38.”

The

graves of the victims of the Boston Massacre are unmarked. Formerly a

beautiful larch tree grew over the spot. It is said to be twenty feet

back from the sidewalk fence and sixty feet south of the Tremont

Building.

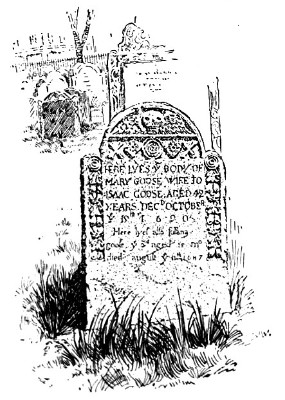

The

grave of Benjamin Woodbridge, the young victim of the duel on the

Common in 1728, is midway between the gate and Park Street Church,

near the fence. The inscription on the upright stone informs us that

he was “a son of the Honourable Dudley Woodbridge Esq’r,” and

“dec’d July ye 3d, in ye 20th year of his age.”

|

Hancock Monument,

Granary Burying Ground |

|

One

stone that many seek here, and some have seemed to identify, is not

to be found, if we are to accept the word of an authoritative

antiquary. This is the tablet marking the grave of “Mother Goose.”

According to the late William H. Whitmore, who, in his “Genesis of

a Boston Myth,” marshaled strong evidence to sustain his assertion,

“Mother Goose” was not Elizabeth Vergoose, the worthy

seventeenth-century matron, as has been alleged; nor was “Mother

Goose” a name that originated in Boston.

In

this yard, as in King’s Chapel Busying Ground, many of the old

stones were years ago ruthlessly shifted from the graves to which

they belonged, which caused the remark of Dr. Holmes that “Epitaphs

were never famous for truth, but the old reproach of ‘Here lies’

never had such a wholesale illustration as in these outraged burial

places, where the stone does lie above and the bones do not lie

beneath.”

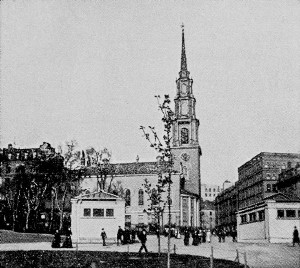

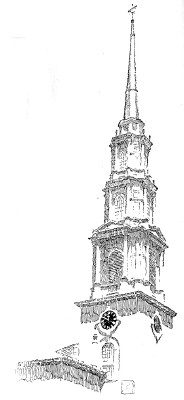

Park

Street Church, with its graceful spire, picturesquely finishing

the corner of Tremont and Park streets, dates from 1809. It is the

best example remaining in the city of the early nineteenth-century

ecclesiastical architecture. It was designed by an English architect,

Peter Banner, but the Ionic and Corinthian capitals of the steeple

were the work of the Bostonian Solomon Willard.

|

|

It

was the first Trinitarian church established after the invasion of

Unitarianism in the Puritan churches, and the fervor with which the

unadulterated orthodox doctrine was preached by its earlier ministers

made its pulpit famous, and led the unrighteous to bestow upon the

point which it faces the title of “Brimstone Corner.” Its history

is notable. It is marked as the place in which “America” was

first publicly sung. The hymn was written by the Rev. Samuel F. Smith

to fit some music for Dr. Lowell Mason, music master of Boston, and

was given for the first time at a children’s celebration here on

July 4, 1832. Here on a preceding 4th of July (1829), William Lloyd

Garrison, then not yet twenty-four years old, gave his first public

address in Boston against slavery. In 1849 Charles Sumner gave his

great address on “The War System of Nations,” at the annual

convention of the American Peace Society, which that year began to

hold its sessions here. This remained the Peace Society’s regular

place of meeting for a long period. The patriotic sermons of the

Civil War preached here by Dr. A. L. Stone (minister of the church

from 1849 to 1866) have been called “a part

of Boston history.” It

was the first Trinitarian church established after the invasion of