IV

COLOR

TAKING

us as a people, by and large, our enjoyment of

color is rather barbaric. We have no objection to a lot of it, and if

the

key is high pitched it does not keep us awake. We have held puritanical

objections to liveliness, whether of color, music, speech, thought or

conduct,

but either we did not recognize it in tints when we saw it, or we are

recovering

somewhat of that youth of the eye that it had before Cromwell blacked

it

for us. We improve in taste as we grow younger, and the hope that

penetrates

far into the future sees, even in our streets, such splendors as were

seen

in Florence in its days of greatness. Flowers can be vehement, though

they

seldom are, for green is a delicious solvent that brings them into

relation,

and often into harmony: and, again, they are of a purity and

transparency

that softens them, even in contrast. If the hues of certain blossoms

are

a bit aggressive in the sun, we are to remember that we seldom see them

in

full light, and that the shadows of leaves, tree trunks and walls do

much

to tone down what else would be too shrill. Then, it is more severe

upon

us to turn a single ray of sharp red or yellow upon the optic nerve

than

to flood it with the same color. We resent little effects; we want

broad

spaces and masses; hence, it is not well to have a quantity of

unrelated

tints in your garden. A solid bank of marigolds, azaleas, or what not,

is

a comfort in its mere aspect; we bask in it, and seem to appropriate

from

its color some delicate material for the building of the spirit, even

as

physicians have discovered varying pathological values in reds, blues,

greens,

yellows, browns, grays and blacks--excitants and sedatives.

In

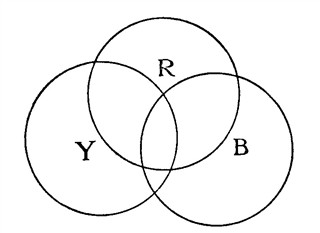

flowers we have every primary and secondary color,

and many shades of each. May I be pardoned if I revert briefly to first

principles. Light can be broken into three primary hues: red, yellow

and

blue. Mix any two of these and you have a secondary.

Where

red overlaps yellow, it makes orange; where it

overlaps blue, it makes purple; where

Fig. 24.

yellow and blue are blended, the result

is green. In these six we have the

rainbow, if you add that deeper blue we call indigo, on its outer rim,

and

that strange liver color which fills the space between the two arches

when

there is a double bow. No color is black. Where all colors blend we

have

the pure white light--if we use the spectrum, because if you mix

pigments

that way you have only a mess. We paint the earth when we plant

flowers,

but a charm of these little friends is the tender and ethereal quality

of

their color. A certain red in paint is thick and dull, but on the petal

of

a rose, peony or rhododendron it gleams like a jewel.

Nature

does not enjoy a reckless mixing of tints. She

softens her distances by toning them to blue, in harmony with the sky

and

sea; her universal green is the most restful and satisfying of all

hues:

with what splendid sweeps of her brush of sun-rays does she change our

woods

in autumn, and what lovely purples and violets we have when the blue of

a

few miles of air blends with the red of the oaks and maples! Our garden

will

be more rich if we treat it as the artist treats his canvas, and avoid

harsh

contrasts and tiny dabs of color. Sow yellow with a generous hand, and

the

earth will smile its content. Unless, to be sure, you are one of those

who

have an aversion to it, in which case, take another color. For myself,

I

find beauty in any tint, but I ask that it be used purely and be kept

from

jangling with every other. And the way to use it, is to use it largely

and

simply. The limits of a garden are so small that you may think you are

forced

to plant primaries side by side, and find that they jar a little. If

you

interpose a touch of that with which you want a color to harmonize the

thing

is done. For instance, you have a bed of red nasturtiums, and you wish

to

put some yellow flowers in the center or about the borders. Then use

orange

nasturtiums as blenders, for they contain both yellow and red. So long

as

you keep to one kind of flower you are in little danger from discords,

because

here again nature attests her esthetics and gives warrant for our own.

For

it is a well-known fact in botany that the flowers of any plant species

will

be restricted in their coloring to two of the primaries with, probably,

the

intermediate tint, that comes of hybridizing. For example, the rose

rejects

blue and keeps to red and yellow. It also adds white, for that does not

commit

the plant which elects it to the use of the third primary. The rose has

almost

every shade of red and pink; it has a gamut of yellows; it even

threatens

to blend these and produce an orange rose, but has gone no closer than

a

salmon tint, so far; but you will find no rose with a purple cast, for

that

would promise a divergence into the third and forbidden primary--blue.

We

shall probably never have a blue rose; at least, the labor of experts

and

centuries in the endeavor to produce one has come to naught. We should

not

care as much for it as for the rose of to-day if we had it, I dare say;

at

least, after the novelty had worn off.

Taking

another family, we find the same rule proved:

the chrysanthemum is yellow, red and white, with blended hues, but

never

blue. In the aster, which it resembles, we have, on the contrary, no

yellow,

but red, blue and white, commonly the red tinged with blue and the blue

showing

a trace of red. In the sweet pea we have blue and red but faint yellow;

in

the azalea, red and yellow, but no blue; the canna and gladiolus

exhibit

various shades of red and yellow, but no blue; in the cineraria we have

a

lively exhibit of ruddy blues, but never a touch of yellow; the

geranium

has several shades of red, with a scarlet that indicates an admixture

of

yellow, but there is no geranium which sows a hint of blue; the bellis

copies

the color range of the aster, hence it is not yellow. There are a few

exceptions;

for instance, we have red, yellow and blue in the columbines; and the

violet

is both yellow and purple, the latter a mixture of red and blue; but

these

exceptions are just enough to prove the rule.

If, however, we

put flowers of unrelated families into close

touch with one another we may perpetrate an inharmony now and then.

Some

boldly throw complementary colors together. A complementary, or

opposite,

is that color which is not contained in the complemented. Thus, red is

the

opposite, or complementary, of green, a compound of the two other

primaries,

and vice versa. If we look intently on yellow, then quickly turn away,

or

close our eyes, we shall see purple, that color representing the

combination

of those other two primaries which yellow is not; if we look away from

blue,

we shall be conscious of orange. Some ingenious pictures were published

a

few years ago called" Ghosts." One looked for half a minute steadily at

a

green rose with red leaves, and turning his head smartly looked into

some

shadowed corner, where after a few seconds, a phantom rose, of normal

color,

duplicating the form that he had impressed upon his eye, appeared,

sometimes

with surprising clearness. In the same way, the picture of a sheeted

figure

in black became a ghost in white when the observer looked away from the

plate,

and off into a darkened room, while a figure in white repeated itself

in

black against a white wall. These experiments account for a good many

supernatural appearances, and are of physiological interest no less.

But

what the eye does as by mechanism is not of necessity a guide to that

which

we shall do with our hands. Complementaries when crudely juxtaposed,

yellow

with purple, and orange with blue, are apt to get to quarreling with

one

another when our backs are turned. Veiled and softened by air and

shadow,

nature's primaries, whether used with opposites or not, seldom clash

disturbingly, but close at hand, in our home plot, it is better to

harmonize

than to contrast. The cooler and quieter colors fit themselves more

easily

to a miscellaneous company than do the gayer ones; indeed, we can make

one

rule suffice: to keep cool and warm colors apart, each in the society

of

its like. The scarlet of geraniums is acid, but it is less endurable

when

supported by a sharp, high green of the same "value," than when offset

by

a darker green. Put a glaring scarlet geranium alongside a bright blue

flower

of any sort, and there is liable to be a riot. Scarlet geraniums are

rather

intractable things, yet apparently the most popular of pot-plants. They

are

effective in borders and masses, but those of a rich China red, and of

pink

and white, are more agreeable and more generally useful.

Complementaries make one another more intense. If we

put the yellowish leaf of a nasturtium against the magenta of a

cineraria,

the former becomes more brilliant, and the latter more rich and solemn.

But

if we put a crimson rose beside the cineraria, and maybe, place a bunch

of

purple grapes before them, we should have three related colors and a

harmony,

eliminating, of course, the nasturtium leaf. If, on the contrary, we

were

to put the cineraria into a combination with a ripe orange and a bit of

cloth

of a bright blue-green--secondaries, all--we should have three

semitones

of a major chord, and semitones make discord when they are not

separated.

Flowers that have a tinge of blue, or red or yellow in common may be

used

safely. If it is, for any reason, necessary to bring colors near one

another

that are addicted to quarreling, use as pale tints of them as possible,

because

white is a wonderful quieter and sweetener, and separate them by green,

or

some medium tint, if they can be kept a little apart. Almost any color

justifies

itself when it is exuberant in quantity, yet the finer and softer tones

of

it win us, in the end.

When in

doubt, use white. That is safe with all colors.

It does not make a harmony with them, any more than green makes

harmony.

We are to regard it rather as light. We can enjoy the effect of marble

statuary,

balustrades, urns, columns, stairs, curbs and walks in formal gardens,

and

the white of this stone grows the softer, yet the surer, for a backing

or

surrounding of somber yews and rhododendrons. It is pure and

passionless

and seems always to express engaging innocence, whether we find it in

the

rose, the hyacinth, the locust or the water-lily. I wish we were not so

frightened by the possibility of it in our costumes, and did not

confine

it to varnished shirts, tin collars and boiler-plate cuffs. Every one

looks

well and younger in white, and nobody looks well in black. So, in

flowers,

white may not dazzle or surprise; it does not gratify the barbaric

fondness

for show; it is not sensational; but it is always welcome, always

comforting;

no less than green it expresses serenity and health.

Click the Little Gardens Icon

to continue to the next chapter.

to continue to the next chapter.

|