(Return to Web Text-ures)

Little Gardens

Content Page

Click Here to return to

the previous section

(HOME)

(Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Little Gardens Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

|

III

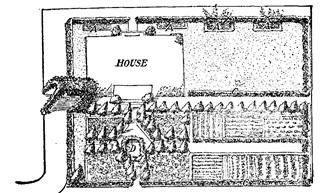

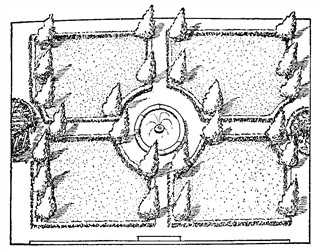

THE COUNTRY YARD IN the yard of the village house--not the summer villa with its acres, but the country home of country people--there is room for more diversity and opportunity for larger effects than in town, for the yard is moderately sure to be larger than that of a city house. The possibilities of beauty and interest in gardens increase as the squares of their area. Yet I think that the same rules for garden-making hold in the country as in the town, namely, that there should be simplicity instead of extravagance, masses instead of scatterings, law instead of lawlessness in respect of color and form, and that there should be a focus, or point of interest, or constructional center. In the country, however, the point of interest need not be in the ground itself. If your house commands a view of a conspicuous mountain, or an expanse of lake, or a handsome clump of wood, or a prospect of a village with a white spire rising above the trees, this can be the focus: the point toward which the lines of your garden will tend. A picture has this dominant note of form, light or color, and its other parts are subordinate to this. If it is otherwise, the effect is confusing, for instead of a balance of light and shade there will be a hundred little lights and shades, each demanding the same attention as the rest. Such a picture tires one after a little while. There is no repose in it. We may not admire a street, for it may be shabby, crowded, discordant in color; but the convergence of its architectural lines toward the vanishing-point reduces it to a certain simplicity, which in itself is dignity, and creates a subtle satisfaction. Far finer are those vistas where the vanishing-point is intercepted by some object of beauty, and where the perspective is marked, not by buildings, but by trees, or hedges, or borders. The view of St. Peter's from some of the Roman gardens, the Pincian, for example, and the view from the Soldiers' Home, at Washington, known as Capitol Vista, both showing aisles and arches of green that end in splendid domes, exemplify this point. Of course, it may easily happen in the country as elsewhere, that the objective point for a garden composition will be lacking. Instead of opening up the paths and alleys on your home ground, it may be desired to lead them nowhere, because they might otherwise carry the eye to a factory, a stable, a stone heap, a dump, a neglected farm, a freight shed or some such unagreeable matter. In a case like that you can do no better than build a hedge and close the view entirely, treating your space thereafter in substantially the same manner as the city yard. In the country we do not hide our horticulture from the eyes of men, because we do not erect big rows of flats and shops between our gardens and the road. A country house demands a margin. It will have a yard in front, as well as a space at the side or back. Hence it has room for show, to put it vulgarly; for the manner has never obtained with us, and let us pray it never will, of building villages solidly, in blocks, as they do in parts of France and England--a fashion passed down from the time when the peasantry clung for employment and protection about the foundations of the castle, and when it was cheaper and easier for their lord to tell them off in rows than to build detached shelters for them. Possibly this very cutting off of some of the people from the fields has led them to prize the beauty of the fields the more; and we have to admit that among the British cotters, the garden, simple as they make it, is a source of more care and satisfaction than among many in our country, although the growing of flowers is now general in America. Gardens, if no bigger than bedrooms, are attached to most of the English cottages, and odd makeshifts are often seen in the attempt to force a growth of flowers where Americans would never think of planting them. It is better to cultivate a rood of space as if you meant it than to plant a whole acre and leave it to the weeds and the elements. And in this country, where land is so abundant, and so cheap, we neglect it. We have too many shabby farms and seedy gardens. When an Englishman has a few feet of space, he makes it count for something. In Bridge End, Warwick, a street of old brick-and-timber cottages has permitted no grace and comfort of shade and lawn, every house being separated from its neighbor by a party wall, and plumping itself as full upon the highway as it dares; yet along the front of these dwellings runs the merest strip of soil, curbed away from the walk, and showing, through the summer, a mass of fine, old-fashioned bloom. This communal park, which is, maybe, a foot and a half wide, masks, or rather softens, the quaint buildings, and gives to them a peculiar picturesqueness. The effect would be worth copying if we built and bedded that way, but in America we are doing better: we are taking down our fences and converting wide districts into a continuous garden. The newer parts of the beautiful city of Hartford are a revelation of what may be accomplished by a community that has civic spirit, good taste and good neighborship. On the edge of the town even the trolley posts are half hid in vines, and one of the ugliest incidents of our streets is thus converted to charm. It is not everywhere that the fence can be abolished. In a visit to a socialist community in Illinois I was puzzled by the number and stoutness of the fences. The disappearing fence in our part of the world means advancing socialism; yet here, in the stronghold of the faith, were the assertions of individual right in property. I asked the reason. "Sure, you don't suppose we could raise anything in our yard," came the answer, "if it wasn't for the fence? The people next door keep hens." Yet there is little need for fences unless it is where cattle abound. A low wall will keep them out, and the wall can be covered with vines. The hedge is a still better safeguard against cows and tramps, unless it is so savory that the cows eat their way through it; it grows stouter instead of weaker every year; it is handsome and grows handsomer, while the fence grows rickety; the advertising fiend can not misuse it, and it merges the surrounded property into its rural environment. Wire fencing has the merit of unobtrusiveness, but if you expect to go to heaven do not use barbed wire. I am not punning when I say it is barbaric. Let your fence be a hedge, thin and tall, low and chunky, according to your neighbors and your tastes. The Englishman likes his high. He demands privacy. He will erect a stone wall inside his hedge, if need be, and strew broken bottles over the top, that poachers and burglars may cut their blooming fingers off when they try to climb over it. He will spoil the view from a country road, and spoil his own, by blocking the prospect in this fashion, and will scare the stranger by an exhibit of "No Trespass" signs in his cabbage-patch--signs such as have likewise appeared in our country within the last forty years. The American seldom wants privacy; isolation yet more rarely. Democracy seems to be preparing the way for a closer social compact, in which individualism must suffer. As a token of it we consider privacy so little that we bring the house close to the road, in order to see the wagons pass, whereas it is in better taste and for better comfort, to withdraw it by at least a dozen or a hundred feet. Then you have some beauty and dignity of setting; you do not cheapen yourself by asking the public to look in at your windows, and to listen to the carols of Mary Ann at the tubs. You may also have all avenue before your house, and if you plan this deftly, not only may you lead it toward the road, but make it a vista with some notable passage of scenery at the end--a road whereby the spirit shall adventure into new spaces. In the country, more than in the city, the garden is a part of the establishment. It may be a dozen of geraniums or petunias, or a few sunflowers, struggling toward the sun, but it has an esthetic meaning in itself, and it relates the house to the landscape. A country garden becomes a part of the dwelling of the mind--part of that outlook for which we forsake cities, and that opens to us distances and eternities that towns conceal. You will, therefore, cultivate your garden as if you meant to live with it. It will not be the brief and little solace of a city yard. Its trees, bushes and perennials will bloom in your affection; they will be fixtures, like the weathering porches of your house; like your old horse, your playful hens, your pranksome dog, and your fruitful cow. You will learn to watch for the budding of your annuals in the spring; you will have a calendar of the seasons at your window. You may even learn to forecast the weather from the conduct of your garden and its animal visitors; for they tell us that pimpernel, or shepherd's weather-glass, opens when sunny weather promises overhead, and partly or wholly closes when storms are brewing; at least, the English peasantry believe so. Goats-beard and marigold also fold together when it darkens, and we have all seen the sleep of oxalis. Countrymen have observed that when the air is clear, when fish dart about, when stagnant water smells, when frogs look dull in color, when swallows fly low, when cobs come out of their webs more freely than in sunlight, then, flowers are apt to shrink from bad weather, and it is time to make things snug. These observations are not my own. I have never seen timidity in flowers, but only regular habits in some of them that incline them to close against too fierce a light, or too dead a darkness. Not only may it be possible to study weather from our yard, but we may know the time of day. At least, it was the dream of Linnd--absurdly Latinized as Linnaeus (for, suppose we were to speak of our first martyr as Lincolnius!)--to own a floral-lock. This botanist, whose work is held in awe by all who have tried to read it, and in admiration by those who haven't, planned a bed of flowers such as had regular times for opening and closing, so that by looking at them he might know the time of day. This is possible. Morning-glories tell us when it is not time to get up, and the evening primrose announces when it is time to play whist and eat. But regardless of these rather strained uses for that which has a higher use than use, you will plant what you can always see and discover promise in it, even when to the eye it is sere and its bare stems give no other voice to the winds than the threnody of winter. The general treatment of a small village yard will not differ materially from that of a yard in the city, but allowance must be made for the greater exuberance of country bloom. City dust and heat and all-night glare, and the reflection of light and warmth from walls and fences and flagstones, do not tend to vegetal health. The country airs and dews will keep the plants in better trim than you can keep them in the city. Hence it is well to plant them a trifle more widely apart than you would in town, and to provide the supports needed for heavy growth. Be careful not to overload your trellises. I know of one man who uses an old steam-pipe for the stem of his trellis, and it supports a goodly weight of roses. In the roomier yard of the village, trees are also a possibility; hence, the shaping and disposition of the beds will be with reference to keeping their contents out of the shade. Larger flowers, too, can be used in the decorative scheme than can be well employed in the city, for, whereas a row of dahlias might seem disproportionate to a space in town, they would harmonize with the large surroundings of a country place. Then, the accidents of topography give chance for pleasant diversities from custom in the garden plan. For example, if there is a stone-pit, or a ledge, or a boulder at the end of the yard, it can be draped with vines and it becomes an element of the picturesque. Over in the Bronx country, opposite Fort George, New York, there is a villa which has, not behind it, but boldly planted in its front, just as the glacier left it, a sunken boulder which has been treated in this manner, and it is worth a good deal more, as a scenic feature, than much of the smugness to be found elsewhere. Again, it may be that a brook or little river will cross your property, and it can be shallowed and widened into a bay where you may plant water-lilies; or, if there is a boggy spot, and you are sure that mosquitoes are not breeding there, it can be utilized for plants like flags, marshmallow, marsh-marigold and forget-me-not. It is wiser that these incidents should be intimate and domestic than to attempt grandiose or park-like effects. Indeed, even our parkmakers, our landscape architects, as they are called, are conceding much to the taste for simplicity. Frederick Law Olmsted, who wrought a needed reform in this respect, aimed to preserve the natural landscape, merely softening it to human uses; to teach, and to satisfy men with the qualities of gentleness and loveliness; to remove from sight all harsh, discordant elements, and to stimulate pleasures in the air, which yield health and content, and calm the fever of social life. In the park, private as well as public, he strove to conceal his art and pleasantly to deceive the wayfarer into the notion that it was all nature in a holiday humor. We must regard our ground as a part of the home, and govern its use and ornament accordingly. · In town nature has been humanized out of likeness to itself, hence, artifice in gardening conforms, not merely in aspect, but in spirit, to its setting. We may, indeed, give it as an axiom, that the more formal the house, the more formal the garden. In the suburb, or the village, we meet nature half-way, and our yard is not an uncovered greenhouse, but rather a link between the joy of home and the lawlessness of the wild. A village garden can be charming if it draws only on tile fields within sight of the house for its materials, and it becomes esthetically and morally useful if it teaches to the villagers the immanence of that beauty which, too often in their conceit, is a far and merchantable quantity. The city yard is an entity. The country yard is foreground for the large and affecting beauty of the hills.  Roses in Profusion. As to trees, it is possible to have too many of them, and too close to the house. Modern landscape architects will not hear your pleading for just one elm before the house, or just a couple of maples at the curb--that is, some of them won't. Sunshine in the house is the first desideratum, and that is proper. Spirits and sanitation both require it. Yet I do not give up the idea of trees on the premises. They should be massed, like the flowers, in groups or pairs of the same variety, not scattered. A field with twenty trees will be spotty and complex if they are isolated, but if arranged in a cluster, or in lines that edge the property, there are seemingly more trees, and certainly more lawn. One big space is worth twenty little spaces. Nor should trees be permitted to close a vista. Rather, they should form a part of it. In forbidding trees to the lawn I mean that they are not to be dotted over it, but that does not prohibit us from using small and graceful trees like the Japanese maple, or weeping birch, or smoke tree, or a lilac, as part of a group in a composition. Be frugal of trees immediately at your doors, at least, if they threaten the light and air in your rooms. 12 am going to violate the law, myself, by having a pine-tree at the corner, when I acquire the right sort of corner. No other tree means so much in its speech, or baffles the listener more piquantly. Its mystery is its charm. In its sighing and whispering yon hear the voices of the sea, the murmur of solitary streams, the questioning of released spirits, the stirring of distant hosts. Its voice is large and cool, and it goes with the flash of stars on January nights and the peal of the wind when the sun begins to fall to the south. Like the other occupants of the home ground, it does not satisfy the eye alone; it addresses the mind and imagination. Perhaps you are frugal, or sociable, and prefer fruit-trees to pines. Better see that your neighbors are supplied with the like, then. I once had a pear-tree and a raspberry patch in a town yard. They were a harrowing experience. Some one had to run out every hour or so, and shoo the boys away--not that we cared about the pears, much, because they were of a variety I have never found anywhere else, being as hard as cocoanuts and as digestible as rocks; indeed, the rogue who stole one deserved to eat it; but the little rascals broke the limbs, impaired the symmetry of the tree, and the premises, trampled the flowers and made the grass as sadly in need of combing as their own heads. I had a notion to put up Charles Dudley Warner's "Children, beware: There is protoplasm here !" But that would have brought them in to look for it. I might have strung an electrified wire about the yard, but the boys who had enjoyed an experience with it would then have led in shoals of other boys, who had not heard that the wire was loaded, in order to initiate them. You suffer from parasites, no matter what you grow-parasites in the forms of insects, weeds and boys. You can kill the weeds and insects. It is by the judicious use of trees that barns, stables, henneries and other structures that were anciently a sorrow to the eye, however much of a pride to the understanding, are concealed from observation, yet the tendency is to put up a barn so much larger than the home, and so much handsomer than the places in which many of the builders were born, that if I were they I would not screen these architectural triumphs by so much as a pea-vine. Where the outbuildings are not a source of pride, however, it is well to thicken the vegetation between them and the house. Perhaps in any case the stable is the better for a hedge about it, for while the upper part of that building may satisfy all demands of an esthetic nature, the lower portions are commonly stained with reminders of earthiness, and green is pleasanter. Beside, apart from the purpose which a hedge will serve in this concealment, its repetition of the long, flat lines of lawn, walk and other appointments is restful. Horizontal lines in a picture or a landscape give a sense of space, yet of repose, while upright lines are excitant--the precipices of Yosemite, for extreme examples. Still, it is more from conditions than from forms that we derive tranquility. There are moods, to be sure, in which one becomes impervious to disturbing suggestions of the city, when we are in the thick of it; when the sun pours serenity from the sky, and the hardness that so often assails our ears and eyes passes out of a world that has ceased to be substance and has become aspect. Our grounds comfort us by the induction of these moods. In them we find the interest and rest which differentiate the home from other parts of earth. The ground of a country place should have a seeming tranquility, signifying that it is a refuge from the storms of life: hence, in laying it off there should be no building up or digging down, without a better reason than precedent. It is a practise in some suburban settlements to place the house on an artificial knoll or terrace two or three feet high. This, I dare say, is a survival of the custom of banking a house with earth, on the setting in of winter, though if we see the lifted house in a low, flat country it doubtless means that the soil is so muddy or so subject to overflow that the residence has to be raised on a manner of stilts, for dryness' sake. This perching of a house on a knoll of such trifling elevation adds nothing to its dignity. It is otherwise with the early nineteenth-century mansions of New England that stand on natural elevations either near the road or at a few rods back from it. As a rule, the farther from a road, say, to a distance of five hundred feet, the more the aspect of importance that a house takes on; but there are many fine old homes in eastern Massachusetts that remain on terraces, left by the lowering of the highway grade before them. Usually the terrace front consists of masonry, and noble elms and maples frame the entrance. There is a sense of leisure and refinement in these old manses. A house that comes flatly to the roadside confesses, in that fact, either that its owner spends much of his time running for trains, hence, he can not spare a moment to cross a garden, or that he is so devoid of self-resource as to occupy himself at the windows, gaping at the pedestrians and teams, when he might be studying sociology, taking naps or practising on the flute. The modern idea is to "get there." So we go by the straightest paths and ask for short cuts, even in our learning. But I admire the reserve, the personality, the implied resource of a house, say, like Longfellow's. Standing thus apart, refusing itself as a unit in an architectural sum, or a social division in a block, it requires trees. They are needed at the curb to shade pedestrians and extend coolness, while they have the effect of sheltering the roof and adding to its privacy, if they are close enough to show above it. In such an instance there is room and even need for a garden in front, especially if the dwelling is colonial in period or in style, for the colonial is formal, while cottages and the usual farmhouses are not. If there are flower-beds before it, possibly the resident may have no care for others in the roomier precincts behind it, yet that is where they show to the best advantage. When a house stands broadside to the road, as is the way in sundry of these old estates, it implies a wider garden than we find in the city where the dwellings squeeze up against the walk and dig their neighbors in the ribs with their elbows. A broad house is pleasanter to view from its garden than a narrow one, and if only because of its amplitude, needs more of ornamental treatment. This it has from Gothic enrichments in the old English halls, and on the Continent it is beginning to take on outside decorations, often painted on gables and blank spaces. Because a large structure fills the eye more nearly, it causes the more discontent if it is ugly. If the garden has area enough, the house is seen at landscape distance, and becomes important as a part of the picture; hence we can devise vistas with the house itself at one end, and a passage of agreeable scenery at the other. These effects, calling for landscape-gardening on a large scale, are hardly to be considered in a book on small grounds. They require at least an acre. The view, however, may be as free to the occupant of a hovel as to the owner of a Biltmore, and where it is present it serves for laying out the guide-lines of a garden composition. Here is a plan, carried into effect in a country place near Philadelphia. The view is supposed to be toward the rear.  Fig. 18: A, Flower-beds; B, vines; C, hedges; D, pool, surrounded by coleus and plants with ornamental leaves.

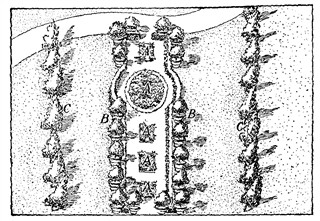

The back of the house is draped with vines, and tubbed yews and cedars are placed along the borders of the walk. The drive, by which carriages may enter the premises from the high road toward a barn, which is rather distant and is not shown here, is spanned by an arched trellis covered with vines, so that a visitor is inducted at once into the garden, unless he enters by the front door. Hedges enclose the whole area and also partition the lawn from the kitchen-garden, so that the vegetables are not in view from the front, although there need be no timidity as to exhibiting these in the country. A place in New Jersey has a broad walk leading from the house toward a lovely wooded and watered valley, this walk containing a chain of flower-beds in the center, a border of lawn on either side, with close-set cedars along their boundaries, and hedges dividing the lawns from the walk.  Fig. 19: A, Flower-beds; B, potted cedars; C, planted evergreens.

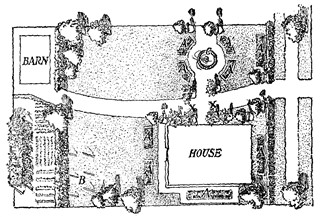

In this case the lawns and walk create the impression of a long reach toward the distance, and they incorporate the scene into the grounds, the more readily as a downward slope at the lower part of the yard conceals the end of the path, where it opens on the high road, so that the imagination travels farther over it than feet can do. For the more usual space in a suburb or a country village, a space of seventy by a hundred, or thereabout, which allows room for the detachment of the house, the next plan is submitted. It divides the territory with a fair degree of economy, and insures a lawn, a formal garden, several flower-beds, a few thickets, a place for drying clothes, a kitchen-garden, a grape-arbor, with hedges about the property and also dividing the utilities at the back from the grounds reserved for pleasure and ornament at the front. In case the tract is more extensive, so that the barn and vegetable patch may be retired to a greater distance, they may be obscured by clusters of low-growing trees, with, perhaps, a single tall one to break their possible monotony. Trees so assembled should not be trimmed or lopped, except of dead or unsightly limbs; indeed, trees that do not close a view are generally to be left to their own devices. This scheme assumes that the pleasanter prospect from the house opens toward the right, across the formal garden, and the broad walk extending from the front door through that reservation gives reach and foreground to it. When the view is distant and commanding, the forespace should be kept as clear as possible, and the house and gardens should take on all the aspect of beauty and endurance that can be afforded. When it is near and romantic--a dell, a cascade, a river passage--it can be framed in vegetation and the avenue can be narrower. If the

shape and size of the ground are much as they

appear in the last plan, but the shed or barn in the corner opens

toward

the road, so that  Fig. 20: A, Flower-beds; B, place for drying clothes; C, fountain, pool, or statue; X, hydrangeas or tubbed trees.

a direct drive is better liked, the

outlines may be altered to something

in this fashion:

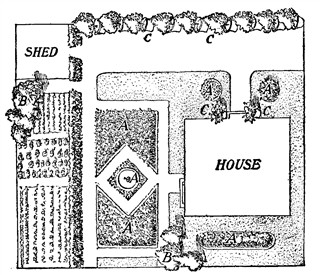

Fig. 21: Flower-beds; B, trees; C, trees or large shrub in pots.

In this scheme the stretch of lawn immediately behind the house serves for the drying of clothes; or, if the house is somewhat aloof from a settlement, or the residents are indifferent to observation, the grassy reach at the side, occupied by the long flower-bed with rounded ends, can be appropriated for that purpose. If the driveway from the road to the barn or shed is muddy or otherwise unpleasant, it can be largely concealed from the view of the house-dwellers by running a hedge along its inner side, opposite the slender strip of green on which potted shrubs have been placed, or large and hardy bushes planted. A hedge is set along the rear of the premises, not to close the view of the "truck patch" merely, but to afford a background for the formal garden, the interest of which can be heightened if the circle in its center is a little pool or fountain. Some of the trees

on the premises ought to be evergreens. You

are grateful for them in winter. A little grove of firs and some rock

work

can diversify a far corner, or both of the remoter corners, in case you

have

no "truck patch," and no barn. And these evergreens need not be pines,

hemlocks,

spruces, cedars, yews, balsams and the like; they can include the

rhododendron,

andromeda, wintergreen, myrtle, and other shrubs that stay bright till

after

Christmas. The variety of smilax known as cat brier scratches and makes

a

tangle, but it is a bit of winter color that serves as well as holly

for

a Christmas decoration. Holly and other berry-bearing bushes are to be

prized

also, for their fruit is as brilliant as flowers at a time when nature

carries

her softest yet most brilliant effects away from the earth and paints

them

over the sky. There are fashions in trees, as there are in shirt-waists

and

parasols, and a present tendency is toward low-growing species, of

"weeping"

habit, though willows are no longer elected. "Weepin' willers" environ

some

New England mansions still, and in central New York a few avenues of

poplars

remain before the abodes of "elegance "--Lombardy poplars, "the proper

tree,

let them say what they will, to surround a gentleman's mansion," as an

old

writer observes. Tubbed trees of dark and solid green, privet, spruce,

the

West Indian bay, palms and rubber-plants are always useful, and in a

small

yard they can surround a floral square or circle. One fashion of

dealing

with them is to make a gravel ring about a flower-bed, place the tubs

upon

this ring, and plant a border of foliage plants still outside of them,

to

conceal the lower part of the tubs, as in Fig. 22.  Fig. 22

If the long dimension of the house fronts on the street and wholly fills the width of the lot the yard at the back will repeat its shape. In such a case the yard might have an ornamental center with subcenters at each end. Of late

we have seen an extension of Spanish mission

architecture, a simple, and in some parts of the land appropriate

style,

not merely for churches, but for residences, and Orange, N. J., has

chosen

it for a jail, determined that her rogues shall go through the form of

going

to church. If a home built in this manner is large, and parked about,

it

makes as pleasant and almost as picturesque an object as those Doric

temples

we used to live in, back in 1820, and the early English castles--of

granite,

sometimes, and stucco at others--that were popular among the rich in

1850.

The mission style really needs room, just as does the Greek and the

Gothic.

Still, in the Southwest, where they continue to use adobe, and

agreeably

follow the Spanish traditions in their building, a mission residence

would

not seem affected or out of place on an ordinary suburban lot; and a

yard

given to grass, with a well, fountain or pool in the center, and an

oblong

or oval walk about it, is a delightful reminder of the monastic gardens

of

California and Mexico, and is possible where it is still the custom to

draw

water from a well, or where the water rises close to the ground level

in

a spring. If a well, it requires a high curb, lest the frequenters fall

in;

but if a basin, then a low curb, or no curb, would be permitted. I have

seen

such an arrangement, with the surrounding walk bordered with box, a

safeguard

that prevented the ramblers from stepping off upon the grass, as it

might

otherwise have pleased them to do. Naturally such borders seem

disproportionately

large, and if they are suffered to attain to any considerable height

they

shut off the view from the walker in his own garden. Yet an alley of

shade

offers a pleasant vista in itself, and will have an air of cloistral

seclusion

that is pleasant to quiet souls; for, as they take the air at evening

they

will realize that they are not exhibiting before possible spectators. A

pool

or fountain not being feasible, it preserves something of an

old-fashioned

aspect for the place if the substitute is made of a sun-dial, with a

narrow

rim of flowers about the pedestal, or a small vine clambering up the

standard.

Arbors are to be viewed askant, unless at a remove from the house. They

contribute to a crowded and top-heavy effect, unless there are

individual

reasons for them, such as the outdoor tea habit or a fondness for

reading

in the shade; but it would suit with a Spanish mission walk if the

farther

reach of it were roofed by a pergola, slight and simple as possible in

construction, and covered with climbing roses and honeysuckle-though

the

latter is so dense in its mode of growth that it shuts off air and

light,

even in winter, unless it is often trimmed--and opening on the yard in

little

arches or square windows. Such a walk would be for lonely

contemplation,

and would be for a poet, or an Englishman.  Fig. 23.

And if an Englishman, and he really wishes seclusion--otherwise he is an American--and he is the owner of the property, he can substitute for the cheap, ugly, unlasting fence, which still survives in the village, a brick wall which will give a support to his vines and a shield to all his garden from the winds. They are not a lasting joy to contemplate--bricks aren't--especially in seasons when the leaves are off, but it is possible to mitigate the plainness of a wall of them by insets of terra-cotta panels or borders, such as are cheaply offered in these times, and wear nearly as well as brick itself. Should a garden be surrounded by a brick wall a large panel in terra cotta could be built into the center at the back, or a seat could be built out from it. The sculptor Pepys Cockerell has recently finished a curious work at Lythe Hall, an estate in Haslemere, England, which consists in a frieze representing a hunt, chiseled from the solid brick of a wall which is farther ornamented by a coping above and buttresses below, and which is surfaced with ivy to the base of the frieze. Were I doomed to live always in a city, I would have the view from the garden no less attractive than the view into it, and I would therefore try to give some dignity to the rear of the house by placing on it a large design in terra cotta, or even in color, and some beauty, by growth of vine and an exhibit of window-boxes. The architectural scheme of the house should be carried into the stone or brick wall enclosing the garden, and--but I must wait till the ship comes home. Click the Little Gardens Icon |