BR’ER RABBIT BR’ER RABBIT is a funny fellow. No wonder that Uncle Remus

makes him

the hero of so many adventures. Uncle Remus had watched him, no doubt,

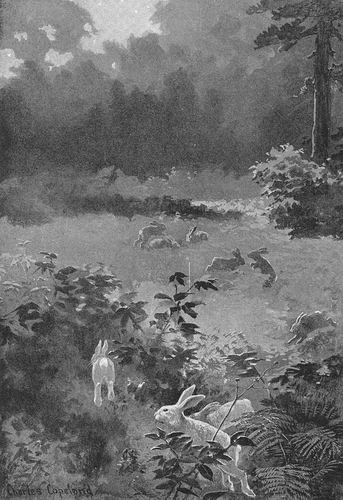

on some moonlight night when he gathered his boon companions together

for a frolic. In the heart of the woods it was, in a little opening

where the moonlight came streaming in through the pines, making soft

gray shadows for hide-and-seek, and where no prowling fox ever dreamed

of looking.

With most of us, the acquaintance with Bunny is too limited

for us

to appreciate his frolicsome ways and his fun-loving disposition. The

tame things which we see about country yards are often stupid, like a

playful kitten spoiled by too much handling; and the flying glimpse of

a bundle of brown fur, scurrying helter-skelter through and over the

huckleberry bushes, generally leaves us staring in astonishment at the

swaying leaves where it disappeared, and wondering curiously what it

was all about. It was only a brown rabbit that you almost stepped upon

in your autumn walk through the woods.

Look under the crimson sumach yonder, there in the bit of

brown

grass, with the purple asters hanging over, and you will find his form,

where he has been sitting all the morning and where he watched you all

the way up the hill. But you need not follow; you will not find him

again. He never runs straight; the swaying leaves there, where he

disappeared, marked the beginning of his turn, whether to right or left

you will never know. Now he has come around his circle and is near you

again — watching you this minute, out of his

bit of brown grass. As

you move slowly away in the direction he took, peering here and there

among the bushes, Bunny behind you sits up straight in his old form

again, with his little paws held very prim, his long ears pointed after

you, and his deep brown eyes shining like the waters of a hidden spring

among the asters. And he chuckles to himself, and thinks how he fooled

you that time, sure.

To see Br’er Rabbit at his best, one must turn hunter,

and learn

how to sit still and be patient. Only you must not hunt in the usual

way; not by day, for then Bunny is stowed away in his form, where one’s

eyes will never find him; not with gun and dog, for then the keen

interest and quick sympathy needed to appreciate any’ phase of animal

life gives place to the coarser excitement of the hunt; and not by

going about after Bunny, for your heavy footsteps and the rustle of

leaves will only send him scurrying away into safer solitudes. Find

where he loves to meet with his fellows, in quiet little openings in

the woods. Go there by moonlight and, sitting still in the shadow, let

your game find you, or pass by without suspicion. This is the best way

to hunt, whether one is after game or only a better knowledge of the

ways of bird and beast.

The best spot I ever found for watching Bunny’s

ways

was on the

shore of a lonely lake in the heart of a New Brunswick forest. A score

of rabbits (or rather hares) lived there who had never seen a man

before, and were as curious about me as a blue jay. No dog’s voice had

ever wakened the echoes within fifty miles; but every sound of the

wilderness they seemed to know a thousand times better than I. The

snapping of the smallest stick under the stealthy tread of fox or

wildcat would send them scurrying out of sight in wild alarm; yet I

watched a dozen of them at play, one night, when a frightened moose

went crashing through the underbrush and plunged into the lake near by,

and they did not seem to mind least.

The spot referred to was the only camping ground on the

lake, —

so Simmo, my Indian guide, assured me; and he knew very well. I

discovered afterward that it was the only cleared bit of land for miles

around; and this the rabbits knew very well. Right in the midst of

their best playground I pitched my tent, while Simmo built his commoosie

near

by, in another little opening. We were tired that night, after a long

day’s paddle in the sunshine on the river. The after-supper chat before

the camp fire was short and sleepy; and we left the lonely woods to the

bats and owls and creeping things, and turned in for the night.

I was just asleep when I was startled by a loud thump

twice

repeated, just like the thump a bear gives an old log with his paw, to

see if it is hollow and contains any insects. I was wide awake in a

moment, sitting up straight to listen. A few minutes passed by in

intense stillness; then, thump! thump! thump! just outside the

tent among the ferns.

I crept slowly out; but, beyond a slight rustle as my

head appeared

outside the tent, I heard nothing, though I waited several minutes and

searched about among the underbrush. But no sooner was I back in the

tent and quiet than there it was again, and repeated three or four

times, now here, now there, within the next ten minutes. I crept out

again, with no better success than before.

This time, however, I would find out about that

mysterious

noise before going back. It is hardly pleasant to go to sleep until one

knows what things are prowling about, especially things that make a

noise like that. A new moon was shining down into the little clearing,

giving hardly enough light to make out the outlines of the great

evergreens. Down among the ferns things were all black and uniform. For

ten minutes I stood there, in the shadow of a big spruce, and waited.

Then the silence was broken by a sudden heavy thump in the bushes just

behind me. I was startled, and wheeled on the instant; as I did so,

some small animal scurried away into the underbrush.

For a moment I was puzzled. Then it flashed upon me that

I was

camped upon the rabbits’ playground. With the, thought came a strong

suspicion that Bunny was fooling me.

Going back to the fire, I raked the coals together and

threw on

some fuel. Next I fastened a large piece of birch bark on two split

sticks behind the fireplace; then I sat down on an old log to wait. The

rude reflector did very well as the fire burned up. Out in front, the

fern tops were dimly lighted to the edge of the clearing. As I watched,

a dark form shot suddenly above the ferns and dropped back again. Three

heavy thumps followed; then the form shot up and down once more. This

time there was no mistake. In the firelight I saw plainly the dangle of

Br’er Rabbit’s long legs, and the flap of his big ears, and the quick

flash of his dark eyes in the reflected light.

I sat there nearly an hour before the why and the how of

the little

joker’s actions became quite clear. This is what happens in such a

case. Bunny comes down from the ridge for his nightly frolic in the

little clearing. While still in the ferns, the big white object

standing motionless in the middle of his playground catches his

attention; and very much surprised, and very much frightened, but still

very curious, he crouches down close to wait and listen. But the

strange thing does not move nor see him.

To get a better view he leaps up high above the ferns

two or three

times. Still the big thing remains quite still and harmless. “Now,”

thinks Bunny, “I'll frighten him, and find out what he is.” Whereupon

he strikes the ground sharply two or three times with his padded hind

foot; then jumps above the ferns quickly to see the effect of his

scare. Once he succeeded very well, when he crept up close behind me,

so close that he did not have to spring up to see the effect. I fancy

him chuckling to himself as he scurried off after my sudden start.

That was the first time that I ever heard Bunny’s

challenge. It

impressed me at the time as one of his most curious pranks; the sound

was so big and heavy for such a little fellow. Since then I have heard

it frequently; and now, sometimes, when I stand at night in the forest

and hear a sudden heavy thump in the underbrush, as if a big moose were

striking the ground and shaking his antlers at me, it does not startle

me in the least. It is only Br’er Rabbit trying to frighten me.

The next night Bunny played us another trick. Before

Simmo went to

sleep he always took off his blue overalls and put them under his head

for a pillow. That was only one of Simmo’s queer ways. While he was

asleep the rabbits came into his little commoosie, dragged the

overalls out from under his head,

and

nibbled them full of holes, for the taste of salt that they found in

them. Not content with this, they played with them all night; pulled

them ‘around the clearing, as threads here and there plainly showed;

then dragged them away into the underbrush and left them.

Simmo’s wrath when he at last found the precious

garments was

comical to behold; when he wore them, with their new polka-dot pattern,

it was still more comical. That night Simmo, to avenge his overalls,

set a deadfall supported by a piece of cord, which he had soaked in

molasses and salt. Which meant that Bunny would nibble the cord, and

bring the log down hard on his own back. So I had to spring it, while

Simmo slept, to save the little fellow’s life and learn more about him.

On the ridge above our tent was a third tiny clearing,

where some

trappers had once made their winter camp. It was there that I watched

the hares one moonlight night from my seat on an old log, just within

the shadow. The first arrival came in with a rush. There was a sudden

scurry behind me, and over the log he came with a flying leap that

landed him on the smooth bit of ground in the middle; where he whirled

around and around with grotesque jumps, like a kitten after its tail.

Only Br’er Rabbit’s tail was too short for him ever to catch it; he

seemed rather to be trying to get a good look at it. Then he went off

like a rocket in a headlong rush through the ferns. Before I knew what

had become of him, over the log he came again in a marvelous jump, and

went tearing around the clearing like a circus horse, varying his

performance now by a high leap, now by two or three awkward hops on his

hind legs, like a dancing bear. It was immensely entertaining.

The third time around he discovered me in the midst of

one of his

antics. He was so surprised that he fell down. In a second he was up

again, sitting very straight on his haunches just in front of me, paws

crossed, ears erect, eyes shining in fear and curiosity. “Who are you?”

he was saying, as plainly as ever rabbit said it. Without moving a

muscle I tried to tell him, and also that he need not be afraid.

Perhaps he began to understand, for he turned his head, as a dog does

when you talk to him. But he was not quite satisfied. “I'll try my

scare on him,” he thought; and thump! thump! thump! sounded

his padded hind foot on the soft ground. It almost made me start again,

it sounded so big in the dead stillness. This last test quite convinced

him that I was harmless and, after a moment’s watching, away he went in

some astonishing jumps into the forest.

A few minutes passed by in quiet waiting before he was

back again,

this time with two or three companions. I have no doubt that he had

been watching me all the time, for I heard his challenge in the brush

just behind my log. The fun now began to grow lively. Around and around

they went, here, there, everywhere; the woods seemed full of rabbits,

they scurried around so. Every few minutes the number increased, as

some new arrival came flying in, and gyrated around like a brown fur

pinwheel. They leaped over everything in the clearing; they leaped over

each other as if playing leap-frog; they vied with each other in the

high jump. Sometimes they gathered together in the middle of the open

space and crept about close to the ground, in and out and roundabout,

like a game of fox and geese. Then they rose on their hind legs and

hopped slowly about in all the dignity of a minuet. Right in the midst

of the solemn affair some mischievous fellow gave a squeak and a big

jump; and away they all went hurry-skurry, for all the world like a lot

of boys turned loose for recess. In a minute they were back again,

quiet and sedate, and solemn as bullfrogs. Were they chasing and

chastising the mischief-maker, or was it only the over-flow of

abundant spirits, as the top of a kettle blows off when the pressure

below becomes resistless?

THE

WOODS SEEMED FULL OF RABBITS Many of the rabbits saw me, I am sure, for they

sometimes gave a

high jump over my foot; and one came close up beside it, and sat up

straight to look me over. Perhaps it was the first corner, for he did

not try his scare again. Like most wild creatures, they have very

little fear of an object that remains motionless at their first

approach and challenge.

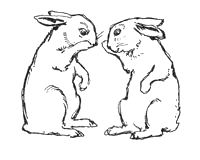

Once there was a curious performance over across the

clearing. I

could not see it plainly, but it looked very much like a boxing match.

A queer sound,

put-a-put-a-put-a-put, first

drew my attention to it. Two rabbits were at the edge of the ferns,

standing up on their hind legs, face to face, and apparently cuffing

each other soundly, while they hopped slowly around and around in a

circle. I could not see the blows but only the boxing attitude, and

hear the sounds as they landed on each other’s ribs. The other rabbits

did not seem to mind it, as they would have done had it been a fight,

but stopped occasionally to watch the two, and then went on with their

fun-making. Since then I have read of tame hares that did the same

thing, but I have never seen it.

At another time the rabbits were gathered together in

the very

midst of some quiet fun, when they leaped aside suddenly and

disappeared among the ferns as if by magic. The next instant a dark

shadow swept across the opening, almost into my face, and wheeled out

of sight among the evergreens. It was Kookooskoos, the big brown owl,

coursing the woods on his nightly hunt after the very rabbits that were

crouched motionless beneath him as he passed. But how did they learn,

all at once, of the coming of an enemy whose march is noiseless as the

sweep of a shadow? And did they all hide so well that he never

suspected that they were about, or did he see the ferns wave as the

last one disappeared, but was afraid to come back after seeing me?

Perhaps Br’er Rabbit was well repaid that time for his confidence.

They

soon came back again, as they would not have done had it been a natural

opening. Had it been one of Nature’s own sunny spots, the owl

would have swept back and forth across it; for he knows the

rabbits’ ways as well as they know his. But hawks and owls

avoid a spot like this, that men have cleared. If they cross it once in

search of prey, they seldom return. Wherever man camps, he leaves

something of himself behind; and the fierce birds and beasts of the

woods fear it, and shun it. It is only the innocent things, singing

birds, and fun-loving rabbits, and harmless little wood mice

— shy, defenseless creatures all

— that take possession of man’s abandoned

quarters, and enjoy his protection. Bunny knows this, I think; and so

there is no other place in the woods that he loves so well as an old

camping ground.

The play was soon over; for it is only in the early part

of the

evening, when Br’er Rabbit first comes out, after sitting still in his

form all day, that he gives himself up to fun, like a boy out of

school. If one may judge, however, from the looks of Simmo’s overalls,

and from the number of times he woke me by scurrying around my tent, I

suspect that he is never too serious and never too busy for a joke. It

is a way he has of brightening the more sober times of getting his own

living, and keeping a sharp lookout for cats and owls and prowling

foxes.

Gradually the playground was deserted, as the rabbits

slipped off

one by one to hunt their supper. Now. and then there was a scamper

among the underbrush, and a high jump or two, with which. some playful

bunny enlivened his search for tender twigs; and at times one, more

curious than the rest, came hopping along to sit erect a moment before

the old log, and look to see if .the strange animal were still there.

But soon the old log was vacant too. Out in the swamp a disappointed

owl sat on his lonely stub that lightning had blasted, and hooted that

he was hungry. The moon looked down into the little clearing with its

waving ferns and soft gray shadows, and saw nothing there to suggest

that it was the rabbits’ nursery.

Down

at the camp a new surprise was awaiting me. Br’er Rabbit was under the

tent fly, tugging away at the salt bag, which I had left there

carelessly after curing a bearskin. While he was absorbed in getting it

out from under the rubber blanket, I crept up on hands and knees, and

stroked him once from ears to tail. He jumped straight up with a

startled squeak whirled in the air, and came down facing me. So we

remained for a full moment, our faces scarcely two feet apart, looking

into each other’s eyes. Then he thumped the earth soundly with his left

hind foot, to show that he was not afraid, and scurried under the fly

and through the brakes in a half circle to a bush at my heels, where he

sat up straight in the shadow to watch me.

But I had seen enough for one night. I left a generous

pinch of

salt where he could find it easily, and crept in to sleep, leaving him

to his own ample devices.

|