MEGALEEP

THE WANDERER MEGALEEP

is the big woodland caribou of the northern wilderness. His Milicete

name means

The Wandering One, but it ought to mean the Mysterious and the

Changeful as

well. If you hear that he is bold and fearless, that is true; and if

you are

told that he is shy and wary and inapproachable, that is also true. For

he is

never the same two days in succession. At once shy and bold, solitary

and

gregarious; restless as a cloud, yet clinging to his feeding grounds,

spite of

wolves and hunters, till he leaves them of his own free will; wild as

Kakagos

the raven, but inquisitive as a blue jay, — he is the most

fascinating and the

least known of all the deer.

I had

always heard and read of Megaleep as an awkward, ungainly animal, but

almost my

first glimpse of him scattered all that to the winds and set my nerves

a-tingling in a way that they still remember. It was on a great chain

of barrens

in the New Brunswick wilderness. I was following the trail of a herd of

caribou

one day, when far ahead a strange clacking sound came ringing across

the snow in

the crisp winter air. I ran ahead to a point of woods that cut off my

view from

a five-mile barren, only to catch breath in astonishment and drop to

cover

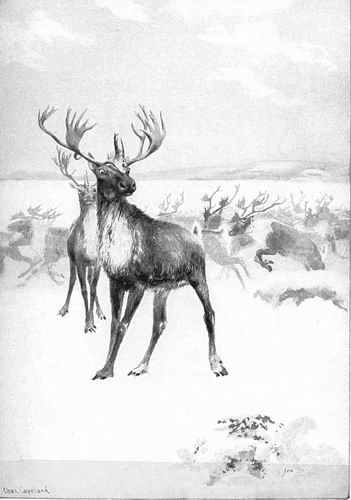

behind a scrub spruce. Away up the barren my caribou, a big herd of

them, were

coming like an express train straight towards me. At first I could make

out only

a great cloud of steam, a whirl of flying snow, and here and there the

angry

shake of wide antlers or the gleam of a black muzzle. The loud clacking

of their

hoofs, sweeping nearer and nearer, gave a snap, a tingle, a wild

exhilaration to

their rush which made one want to shout and swing his hat. Presently I

could

make out the individual animals through the cloud of vapor that drove

down the

wind before them. They were going at a splendid trot, rocking easily

from side

to side like pacing colts, — power, grace, tirelessness in

every stride. Their

heads were high, their muzzles up, the antlers well back on heaving

shoulders.

Jets of steam burst from their nostrils at every bound ; for the

thermometer was twenty below zero, and the air snapping. A

cloud of snow whirled out and up behind them; through it the antlers

waved like

bare oak boughs in the wind; the sound of their hoofs was like the

clicking of

mighty castanets. — “Oh for a sledge and bells!” I thought;

for Santa Claus

never had such a team.

THE

LEADING BULLS GAVE A FEW MIGHTY BOUNDS. So

they came on swiftly, magnificently, straight on to the cover behind

which I

crouched with nerves thrilling as at a cavalry charge, till I sprang to

my feet

with a shout and swung my hat; for, as there was meat enough in camp, I

had

small wish to use my rifle, and no desire whatever to stand that rush

at close

quarters and be run down. There was a moment of wild confusion out on

the barren

just in front of me. The long swinging trot, that caribou never change

if they

can help it, was broken into an awkward jumping gallop. The front rank

reared,

plunged, snorted a warning, but were forced onward by the pressure

behind. Then

the leading bulls gave a few mighty bounds, which brought them close up

to me,

but left a clear space for the frightened, crowding animals behind. The

swiftest

shot ahead to the lead; the great herd lengthened out from its compact

mass;

swerved easily to the left, as at a word of command; crashed through

the fringe

of evergreen in which I had been hiding, — out into the

open with a wild

plunge and a loud cracking of hoofs, where they all settled into their

wonderful

trot again and kept on steadily across the barren below.

That

was the sight of a lifetime. One who saw it could never again think of

caribou

as ungainly animals. Megaleep belongs to the tribe of Ishmael. Indeed,

his Latin

name, as well as his Indian one, signifies The Wanderer; and if you

watch him a

little while you will understand perfectly why he is so called. The

first time I

ever met him in summer was at twilight, on a wilderness lake. I was

sitting in

my canoe by the inlet, wondering what kind of bait to use for a big

trout which

lived in an eddy behind the rock, and which disdained everything I

offered him.

The swallows were busy, skimming low and taking the young mosquitoes as

they

rose’ from the water. One dipped to the surface near the eddy. As he

came down

I saw a swift gleam in the depths below. He touched the water; there

was a

swirl, a splash — and the swallow was gone. The trout had

him.

Then

a cow caribou came out of the woods to a grassy point above me to

drink. First

she wandered all over the point, making it look afterwards as if a herd

had

passed. Then she took a sip of water by a rock, crossed to my side of

the point

and took a sip there; then to the end of the point, and another sip;

then back

to the first place. A nibble of grass, and she waded far out from shore

to sip

there; then back, with a nod to a lily pad, and a sip nearer the brook.

Finally

she meandered a long way up the shore out of sight, and when I picked

up the

paddle to go, she came back again. Truly a Wandergeist

of the woods, like the plover of the coast, who never knows what he

wants,

nor why he circles about so, nor where he is going next.

If

you follow the herds over the barrens and through the forest in winter,

you find

the same wandering, unsatisfied creature. And if you are a sportsman

and a keen

hunter, with well-established ways of trailing and stalking, you will

be driven

to desperation a score of times before you get acquainted with

Megaleep. He

travels enormous distances without any known object. His trail is

everywhere; he

is himself nowhere. You scour the country for a week, crossing

innumerable

trails, thinking the surrounding woods must be full of caribou; then a

man in a

lumber camp, where you are overtaken by night, tells you that he saw

the herd

you are after down on the Renous barrens, thirty miles below. You go

there, and

have the same experience, — signs everywhere, old signs,

new signs, but never

a caribou. And, ten to one, while you are there, the caribou are

sniffing your

snowshoe track suspiciously back on the barrens that you have just

left.

Even

in feeding, when you are hot on their trail and steal forward,

expecting to see

them every moment, it is the same endless story. They dig a hole

through four

feet of packed snow to nibble the reindeer lichen that grows everywhere

on the

barrens. Before it is half eaten they wander off to the next barren and

dig a

larger hole; then away to the woods for the gray-green hanging moss

that grows

in the spruces. Here is a fallen tree half covered with the rich food.

Megaleep

nibbles a bite or two, then wanders away and away in search of another

tree like

the one he has just left.

And

when you find him at last, the chances are still against you. You are

stealing

forward cautiously when a fresh sign attracts attention. You stop to

examine it

a moment. Something gray, dim, misty, seems to drift like a cloud

through the

trees ahead. You scarcely notice it till, on your right, a stir, and

another

cloud, and another — the caribou, quick, a score of them! But before

your rifle

is up and you have found the sights, the gray things melt into the gray

woods

and drift away; and the stalk begins all over again.

The

reason for this restlessness is not far to seek. Megaleep’s ancestors

followed

regular migrations in spring and autumn, like the birds, on the

unwooded plains

beyond the Arctic Circle. Megaleep never migrates; but the old instinct

is in

him and will not let him rest. So he wanders through the year, and is

never

satisfied.

Fortunately

nature has been kind to Megaleep, in providing him with means to

gratify his

wandering disposition. In winter, moose and red deer must gather into

yards and

stay there. With the first heavy storm of December, they gather in

small bands

on the hardwood ridges, and begin to make paths in the snow, — long,

twisted,

crooked paths, running for miles in every direction, crossing and

recrossing in

a tangle utterly hopeless to any head save that of a deer or moose.

These paths

they keep tramped down and more or less open all winter, so as to feed

on the

twigs and bark growing on either side. Were it not for this curious

habit, a

single severe winter would leave hardly a moose or a deer alive in the

woods;

for their hoofs are sharp and sink deep; with six feet of snow on a

level they

can run scarcely a mile outside their paths without becoming hopelessly

stalled

or exhausted.

It is

this great tangle of paths, by the way, which constitutes a deer or a

moose

yard.

But

Megaleep the Wanderer makes no such provision; he depends upon Mother

Nature to

take care of him. In summer he is brown, like the great tree trunks

among which

he moves unseen. Then the frog of his foot expands and grows spongy, so

that he

can cling to the mountain-side like a goat, or move silently over the

dead

leaves. In winter he becomes a soft gray, the better to fade into a

snowstorm,

or to stand concealed in plain

sight on the edges of the gray, desolate barrens that he loves. Then

the frog of

his foot arches up out of the way; the edges of his hoof grow sharp and

shell-like, so that he can travel over glare ice without slipping, and

cut the

crust to dig down for the moss upon which he feeds. The hoofs,

moreover, are

very large and deeply cleft, so as to spread widely when his weight is

on them.

When you first find his track in the snow, you rub your eyes, thinking

that a

huge ox must have passed that way. The dew-claws are also large, and

the ankle

joint so flexible that it lets them down upon the snow. So Megaleep has

a kind

of natural snowshoe with which he moves easily over the crust, and,

except in

very deep, soft snows, wanders at will, while other deer are prisoners

in their

yards. It is the snapping of these loose hoofs and ankle joints that

makes the

merry clacking sound as caribou run.

Sometimes,

however, they overestimate their abilities, and their wandering

disposition

brings them into trouble. Once I found a herd of seven up to their

backs in soft

snow, and tired out, — a strange condition for caribou to be in. They

were

taking the affair philosophically, resting till they should gather

strength to

flounder to some spruce tops, where moss was plenty. When I approached

gently on

snowshoes (I had been hunting them diligently the week before; but this

put a

different face on the matter) they gave a bound or two, then settled

deep in the

snow, and turned their heads and said with their great soft eyes: “You

have

hunted us. Here we are, at your mercy.”

They

were very much frightened at first; then I thought they grew a bit

curious, as I

laid my rifle aside and sat down peaceably in the snow to watch them.

One — a

doe, more exhausted than the others, and famished — even

nibbled a bit of moss

that I pushed near her with a stick. I had picked it with gloves, so

that the

smell of my hand was not on it. After an hour or so, if I moved softly,

they let

me approach quite up to them without shaking their antlers or

renewing their desperate attempts to flounder away. But I did not touch

them. That is a degradation which no wild creature will permit when he

is free;

and I would not take advantage of their helplessness.

“Did

they starve in the snow?” you ask. Oh, no! I went to the place next day

and

found that they had gained the spruce tops, ploughing through the snow

in great

bounds, following the track of the strongest, which went ahead to break

the way.

There they fed and rested, then went to some dense thickets where they

passed

the night. In a day or two the snow settled and hardened, and they took

to their

wandering again.

Later,

in hunting, I crossed their tracks several times, and once I saw them

across a

barren; but I left them undisturbed, to follow other trails. We had

eaten

together; they had fed from my hand; and there is no older truce on

earth than

that; not even in the unchanging East, where it originated.

Megaleep

in a storm is a most curious creature, the nearest thing to a ghost to

be found

in the woods. More than other animals he feels the falling barometer.

His

movements at such times drive you to desperation, if you are following

him; for

he wanders unceasingly. When the storm breaks he has a way of appearing

suddenly, as if he were seeking you, when, by his trail, you thought

him miles

ahead. And the way he disappears — just melts into the thick driving

flakes and

the shrouded trees — is most uncanny. Eight or ten caribou

once played

hide-and-seek with me that way, giving me vague glimpses here and

there, drawing

near to get my scent, yet keeping me looking up wind into the driving

snow,

where I could see nothing distinctly. And all the while they drifted

about like

so many huge flakes of the storm, watching my every movement, seeing me

perfectly.

At

such times they fear little, and even lay aside their usual caution. I

remember

trailing a large herd, one day, from early morning, keeping near them

all the

time and jumping them half a dozen times, yet never getting a glimpse

because of

their extreme watchfulness. For some reason they were unwilling to

leave a small

chain of barrens.

Perhaps

they knew the storm was coming, when they would be safe; and so,

instead of

swinging off into a ten-mile straightaway trot at the first alarm, they

kept

dodging back and forth within a two-mile circle. At last, late in the

afternoon,

I followed the trail to the edge of dense evergreen thickets. Caribou

generally

rest in open woods or on the windward edge of a barren. Eyes for the

open, nose

for the cover, is their motto. And I thought,” They know perfectly well

I am

following them, and so have lain down in that tangle. If I go in, they

will hear

me; a wood mouse could hardly keep quiet in such a place. If I go

round, they

will catch my scent. If I wait, so will they. If I jump them, the scrub

will

cover their retreat perfectly.”

As

I sat down in the snow to think it over, a heavy rush, deep within the

thicket,

told me that something — not I, certainly — had again started

them. Suddenly

the air darkened, and above the excitement of the hunt I felt the storm

coming.

A storm in the woods is no joke when you are six miles from camp

without axe or

blanket. I broke away from the trail and started for the head of the

second

barren on the run. If I make that, I was safe; for there was a stream

hard by,

which led to camp; and one cannot very well lose a stream, even in a

snowstorm.

But before I was out of the big timber the flakes were driving thick

and soft in

my face. Another half-mile, and one could not see fifty feet in any

direction.

Still I kept on, holding my course by the wind and my compass. Then, at

the foot

of the second barren, my snowshoes stumbled into great depressions in

the snow,

and I found myself on the fresh trail of my caribou again. “If I am

lost, I

will at least have a caribou steak, and a skin to wrap me up in,” I

said, and

plunged after them. As I went, the old Mother Goose rhyme of nursery

days came

back and set itself to hunting music:

|

Bye, baby

bunting,

Daddy ‘s gone a-hunting,

For to catch a rabbit skin

To wrap the baby bunting in.

|

Presently

I began to sing it aloud. It cheered one up in the storm, and the lilt

of it

kept time to the leaping kind of gallop, which is the easiest way to

run on

snowshoes: “Bye, baby bunting; bye, baby bunting — Hello!”

A dark mass loomed suddenly before me on the open barren. The storm

lightened a

bit, before setting in heavier; and there were the caribou, just in

front of me,

standing in a compact mass, the weaker ones in the middle. They had no

thought

nor fear of me, apparently; they showed no sign of anger or uneasiness.

Indeed,

they barely moved aside as I snow-shoed up, in plain sight, without any

precaution whatever. And these were the same animals that had fled upon

my

approach at daylight, and that had escaped me all day with marvelous

cunning.

As

with other deer, the storm is Megaleep’s natural protector. When it

comes he

thinks that he is safe; that nobody can see him; that the falling snow

will fill

his tracks and kill his scent; and that whatever follows must speedily

seek

cover for itself. So he gives up watching, and lies down where he will.

So far

as his natural enemies are concerned, he is safe in this; for lynx and

wolf and

panther seek shelter with a falling barometer. They can neither see nor

smell;

and they are all afraid. I have often noticed that, among all animals

and birds,

from the least to the greatest, there is always a truce when the storms

are out.

But

the most curious thing I ever stumbled into was a caribou school. That

sounds

queer; but it is more common in the wilderness than one thinks. All

gregarious

animals have perfectly well-defined social regulations, which the young

must

learn and respect. To learn them, they go to school in their own

interesting

way.

The

caribou I am speaking of now are all woodland caribou — larger, finer

animals

than the barren-ground caribou of the desolate unwooded regions farther

north.

In summer they live singly, rearing their young in deep forest

seclusions. There

each one does as he pleases. So when you meet a caribou in summer, he

is a

different creature, and has more unknown and curious ways than when he

runs with

the herd in midwinter.

I

remember a solitary old bull that lived on the mountain-side opposite

my camp,

one summer, — a most interesting mixture of fear and boldness, of

reserve and

intense curiosity. After I had followed him a few times and he found

that my

purpose was wholly peaceable, he took to hunting me in the same way,

just to

find out who I was, and what queer thing I was doing. Sometimes I would

see him

at sunset, on a dizzy cliff across the lake, watching for the curl of

smoke or

the coming of a canoe. And when I jumped in for a swim and went

splashing,

dog-paddle way, about the island where my tent was, he would walk about

in the

greatest excitement, and start a dozen times to come down; but always

he ran

back for another look, as if fascinated. Again he would come down on a

burned

point near the deep hole where I was fishing, and, hiding his body in

the

underbrush, would push his horns up into the bare branches of a

withered

shrub, so as to make them inconspicuous, and stand watching me. As long

as he

was quiet, it was impossible to see him there; but I could always make

him start

nervously by flashing a looking-glass, or flopping a fish in the water,

or

whistling a jolly Irish jig. And when I tied a bright tomato can to a

string and

set it whirling round my head, or set my handkerchief for a flag on the

end of

my trout rod, then he could not stand it another minute, but came

running down

to the shore, to stamp and fidget and stare nervously, and scare

himself with

twenty alarms while trying to make up his mind to swim out and satisfy

his

burning desire to know all about it. — But I am forgetting

the caribou

schools.

Wherever

there are barrens — treeless plains in the midst of dense

forest — the caribou

collect in small herds as winter comes on, following the old gregarious

instinct. Then each one cannot do as he pleases any more; and it is for

this

winter and spring life together, when laws must be known, and the

rights of the

individual be laid aside for the good of the herd, that the young are

trained.

One

afternoon in late summer I was drifting down the Toledi River, casting

for

trout, when a movement in the bushes ahead caught my attention. A great

swampy

tract of ground, covered with grass and low brush, spread out on either

side the

stream. From the canoe I made out two or three waving lines of bushes,

where

some animals were making their way through the swamp towards a strip of

big

timber, which formed a kind of island in the middle.

Pushing

my canoe into the grass, I made for a point just astern of the nearest

quivering

line of bushes. A glance at a bit of soft ground showed me the trail of

a mother

caribou with her calf. I followed cautiously, the wind being in my

favor. They

were not hurrying, and I took good pains not to alarm them.

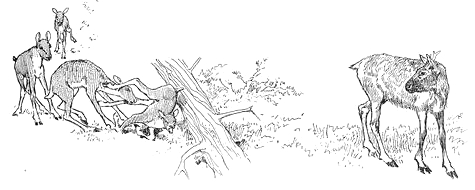

When

I reached the timber and crept like a snake through the underbrush,

there were

the caribou, five or six mother animals and nearly twice as many little

ones,

well grown, which had evidently just come in from all directions. They

were

gathered in a natural opening, fairly clear of bushes, with a fallen

tree or

two, which served a good purpose later. The sunlight fell across it in

great

golden bars, making light and shadow to play in; all around was the

great marsh,

giving protection from enemies; dense underbrush screened them from

prying

eyes — and this was their schoolroom.

The

little ones were pushed out into the middle, away from the mothers to

whom they

clung instinctively, and were left to get acquainted with each other;

which they

did very shyly at first, like so many strange children. It was all new

and

curious, this meeting of their kind; for till now they had lived in

dense

solitudes, each one knowing no living creature save its own mother.

Some were

timid, and backed away as far as possible into the shadow, looking with

wild,

wide eyes from one to another of the little caribou, and bolting to

their

mothers’ sides at every unusual movement. Others were bold, and took to

butting at the first encounter. But

careful, kindly eyes watched over them. Now and then a mother caribou

would come

from the shadows and push a little one gently from his retreat, under a

bush,

out into the company. Another would push her way between two heads that

lowered

at each other threateningly, and say with a warning shake of her head

that

butting was no good way to get along together. I had once thought,

watching a

herd on the barrens through my glasses, that they are the gentlest of

animals

with each other. Here in the little school, in the heart of the swamp,

I found

the explanation of things.

For

over an hour I lay there and watched, my curiosity growing more eager

every

moment; for most of what I saw I could not comprehend, having no key,

nor

understanding why certain youngsters, who needed reproof according to

my

standards, were let alone, and others kept moving constantly, and still

others

led aside often to be talked to by their mothers. But at last came a

lesson in

which all joined, and which could not be misunderstood, not even by a

man. It

was the jumping lesson.

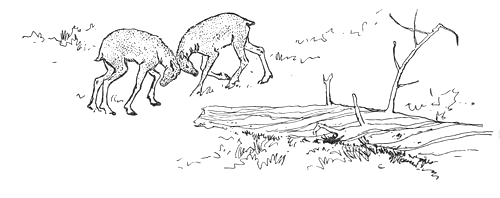

Caribou

are naturally poor jumpers. Beside a deer, who often goes out of his

way to jump

a fallen tree just for the fun of it, they have no show whatever;

though they

can travel much farther in a day and much easier. Their gait is a

swinging trot,

from which it is impossible to jump; and if you frighten them out of

their trot

into a gallop and keep them at it, they soon grow exhausted. Countless

generations on the northern wastes, where there is no need of jumping,

have bred

this habit, and modified their muscles accordingly. But now a race of

caribou

has moved south into the woods, where great trees lie fallen across the

way, and

where, if Megaleep is in a hurry or there is anybody behind him,

jumping is a

necessity. Still he does not like it, and avoids it whenever possible.

The

little ones, left to themselves, would always crawl under a tree, or

trot round

it. And this is another thing to overcome, and another lesson to be

taught in

the caribou school.

As

I watched them, the mothers all came out from the shadows and began

trotting

round the opening, the little ones keeping close as possible each one

to its

mother’s side. Then the old ones went faster; the calves were left in a

long

line stringing out behind. Suddenly the leader veered in to the edge of

the

timber and went over a fallen tree with a jump; the cows followed

splendidly,

rising on one side, falling gracefully on the other, like gray waves

racing past

the end of a jetty. But the first little one dropped his head

obstinately at the

tree and stopped short. The next one did the same thing; only he ran

his head

into the first one’s legs and knocked them out from under him. The

others

whirled with a ba-a-a-ah! and scampered round the tree and up to their

mothers,

who had now turned and stood watching anxiously to see the effect of

their

lesson. Then it began over again.

It

was true kindergarten teaching; for, under guise of a frolic, the

calves were

being taught a needful lesson, — not only to jump, but, far

more important

than that, to follow a leader, and to go where he goes without question

or

hesitation. For the leaders on the barrens are wise old bulls that make

no

mistakes. Most of the little caribou took to the sport very well, and

presently

followed the mothers over the low hurdles. But a few were timid; and

then came

the most intensely interesting bit of the whole strange school, when a

little

one would be led to a tree and butted from behind till he took the

jump.

There

was no “consent of the governed” in that governing. The mother knew,

and the

calf didn’t, just what was good for him.

It

was this last lesson that broke up the school. Just in front of my

hiding place

a tree fell out into the opening. A mother caribou brought her calf up

to this

unsuspectingly, and leaped over, expecting the little one to follow. As

she

struck she whirled like a top and stood like a beautiful statue, her

head

pointing in my direction. Her eyes were bright with fear, the ears set

forward,

the nostrils spread to catch every tainted atom from the air. Then she

turned

and glided silently away, the little one close to her side, looking up

and

touching her frequently, as if to whisper, What

Is It? What Is It? but making no sound. There was no signal given, no

alarm of any kind that I could understand; yet the lesson stopped

instantly. The

caribou glided away like shadows. Over across the opening a bush

swayed; here

and there a leaf quivered, as if something touched its branch. Then the

schoolroom was empty and the woods all still.

There

is another curious habit of Megaleep; and this one I am utterly at a

loss to

account for. When he is old and feeble, and the tireless muscles will

no longer

carry him with the herd over the wind-swept barrens, and he falls sick

at last,

he goes to a spot far away in the woods, where generations of his

ancestors have

preceded him, and there lays him down to die. It is the caribou burying

ground;

and all the animals of a certain district, or a certain herd, will go

there when

sick or sore wounded, if they have strength enough to reach the spot.

For it is

far away from the scene of their summer homes and their winter

wanderings.

I

know one such place, and visited it twice from my summer camp. It is in

a dark

tamarack swamp by a lonely lake, at the head of the Little-South-West

Miramichi

River, in New Brunswick. I found it, one summer, when trying to force

my way

from the big lake to a smaller one, where trout were plenty. In the

midst of the

swamp I stumbled upon a pair of caribou skeletons; which surprised me,

for there

were no hunters within a hundred miles, and at that time the lake had

been for

many years unvisited. I thought of fights between bucks, and bull

moose, — how

two bulls will sometimes lock horns in a rush, and are too weakened to

break the

lock, and so die together of exhaustion. Caribou are more peaceable;

they rarely

fight that way; and besides, the horns here were not locked together,

but lying

well apart. As I searched about, looking for the explanation of things,

thinking

of wolves, yet wondering why the bones were not gnawed, I found another

skeleton, much older, then four or five more; some quite fresh, others

crumbling

into mould. Bits of old bone and some splendid antlers were scattered

here and

there through the underbrush; and when I scraped away the dead leaves

and moss,

there were older bones and fragments mouldering beneath.

I

scarcely understood the meaning of it at the time; but since then I

have met

men, Indians and hunters, who have spent much time in the wilderness,

who speak

of “bone yards” which they have discovered, — places where

they can go at

any time and be sure of finding a good set of caribou antlers. And they

say that

the caribou go there to die.

All

animals, when feeble with age, or sickly, or wounded, have the habit of

going

away, deep into the loneliest coverts, and there lying down where the

leaves

will presently cover them. That is why one rarely finds a dead bird or

animal in

the woods, where thousands die yearly. Even your dog, that was born and

lived by

your house, often disappears when you thought him too feeble to walk.

Death

calls him gently; the old wolf stirs deep within him, and he goes away,

where

the master he served will never find him. And so with your cat, which

is only

skin-deep a domestic animal; and so with your canary, which in death

alone would

be free, and beats his failing wings against the cage in which he lived

so long

content. But these all go away singly, each to his own place. The

caribou is the

only animal I know that remembers, when his separation comes, the ties

which

bound him to the herd, winter after winter, through sun and storm, in

the forest

where all was peace and plenty, on the lonely barrens where the gray

wolf howled

on his track; so that he turns, with his last strength, from the herd

he is

leaving to the greater herd which has gone before him — still

following his

leaders, remembering his first lesson to the end.

Sometimes

I have wondered whether this also were taught in the caribou school;

whether,

once in his life, Megaleep were led to the spot and made to pass

through it, so

that he should feel its meaning and remember. That is not likely; for

the one

thing which an animal cannot understand is death.

And

there were no signs of living caribou anywhere near the place that I

discovered;

though down at the other end of the lake their tracks were everywhere.

There

are other questions, which one can only ask without answering. Is this

silent

gathering merely a tribute to the old law of the herd; or does

Megaleep, with

his last strength, still think to cheat his old enemy, and go where the

wolf,

that followed him all his life, shall not find him? How was his resting

place

first selected, and what leaders searched out the ground? What sound or

sign,

what murmur of wind in the pines, or lap of ripples on the shore, or

song of the

veery at twilight made them pause and say, Here

is the place?

How does he know, he whose thoughts are all of life and who never

looked on

death, where the great silent herd is that no caribou ever sees but

once? And

what strange instinct guides Megaleep to the spot where all his

wanderings end

at last?

|