KEEONEKH THE FISHERMAN

WHEREVER

you find Keeonekh the otter you find three other things: wildness,

beauty, and running water that no winter can freeze. There is also good

fishing, but that will profit you little; for after Keeonekh has

harried a pool it is useless to cast your fly or minnow there. The

largest fish has disappeared — you will find his bones and a

fin or two on the ice or the nearest bank — and the little

fish are still in hiding after their fright.

Conversely, wherever you find the three elements mentioned you will

also find Keeonekh, if your eyes know how to read the signs aright.

Even in places near the towns, where no otter has been seen for

generations, they are still to be found leading their shy wild life, so

familiar with every sight and sound of danger that no eye of the many

that pass by ever sees them. No animal has been more persistently

trapped and hunted for the valuable fur that he bears; but Keeonekh is

hard to catch and quick to learn. When a family have all been caught or

driven away from a favorite stream, another otter speedily finds the

spot in some of his winter wanderings after better fishing, and,

knowing well from the signs that others of his race have paid the sad

penalty for heedlessness, he settles down there with greater

watchfulness, and enjoys his fisherman’s luck.

In the spring he brings a mate to share his rich living. Soon a family

of young otters go a-fishing in the best pools, and explore the stream

for miles up and down. But so shy and wild and quick to hide are they

that the trout fishermen who follow the river, and the ice fishermen

who set their tilt-ups in the pond below, and the children who gather

cowslips in the spring have no suspicion that the original proprietors

of the stream are still on the spot, jealously watching and resenting

every intrusion.

Occasionally the wood choppers cross an unknown trail in the snow, a

heavy trail, with long, sliding, down-hill plunges which look as if a

log had been dragged along. But they too go their way, wondering a bit

at the queer things that live in the woods, but not understanding the

plain records that the queer things leave behind them. Did they but

follow far enough, they would find the end of the trail in open water,

and on the ice beyond the signs of Keeonekh’s fishing.

I remember one otter family whose den I found, when a boy, on a stream

between two ponds within three miles of the town house. Yet the oldest

hunter could barely remember the time when the last otter had been

caught or seen in the county.

I was sitting very still in the bushes on the bank, one day in spring,

watching for a wood duck. Wood duck lived there, but the cover was so

thick that I could never surprise them. They always heard me coming and

were off, giving me only vanishing glimpses among the trees; or else

they would hide among the sedges or under the tall water grass that

hung over the bank, where no eye could find them, and lie low, like

Br’er Rabbit, until I went by. So the only way to see them a

beautiful sight they were — was to sit still in hiding, for

hours if need be, until they came gliding by, all unconscious of the

watcher.

As I waited a large animal came swiftly up stream, just his head

visible, with a long tail trailing behind. He was swimming powerfully,

steadily, straight as a string; but, as I noted with wonder, he made no

ripple whatever, sliding through the water as if greased from nose to

tail. Just above me he dived, and I did not see him again, though I

watched up and down stream breathlessly for him to reappear.

I had never seen such an animal before, but I knew somehow that it was

an otter, and I drew back into better hiding with the hope of seeing

the rare creature again. Presently another otter appeared, coming up

stream and disappearing in exactly the same way as the first. But

though I stayed all the afternoon I saw nothing more.

After that I haunted the spot every time I could get away, creeping

down to the river bank and lying in hiding, hours long at a stretch;

for I knew now that the otters lived there, and they gave me many

glimpses of a life I had never seen before.

Soon I found their den. It was in a bank opposite my hiding place, and

the entrance was among the roots of a great free, under water, where no

one could have possibly found it, if the otters had not themselves

shown the way. In their approach they always dived while yet well out

in the stream, and so entered their door unseen. When they came out

they were quite as careful, always swimming some distance under water

before coming to the surface. It was several days before my eye could

trace surely the faint undulation of the water above them, and so

follow their course to their doorway. Had not the water been shallow I

should never have found it; for they are the most wonderful of

swimmers, making no disturbance on the surface, and gliding beneath

the water with the faintest suggestion of a ripple to tell what is

passing — like the wake of a big pickerel, coming back to his

den under the bank after his frog-hunting among the lily pads.

Those were among the happiest watching hours that I have ever spent in

the woods. The game was so large, so utterly unexpected; and I had the

wonderful discovery all to myself. Not one of the half-dozen boys and

men who occasionally, when the fever seized them, trapped muskrat in

the wild meadow, a mile below, or the rare mink that hunted frogs in

every brook, had any suspicion that such splendid fur was to be had for

the trapping.

Sometimes a whole afternoon would go slowly by, filled with the sounds

and sweet smells of the woods, and not a ripple would break the dimples

of the stream before me. But when, one late afternoon, just as the

pines across the stream began to darken against the western light, a

string of silver bubbles shot across the stream and a big otter rose to

the surface with a pickerel in his mouth, all the watching that had not

well repaid itself was swept out of the reckoning. He came swiftly

towards me, put his fore paws against the bank, gave a wriggling jump,

— and there he was, not twenty feet away, holding the

pickerel down with his fore paws, his back arched like a frightened

cat, and a tiny stream of water trickling down from the tip of his

heavy, pointed tail, as he ate his fish with immense relish.

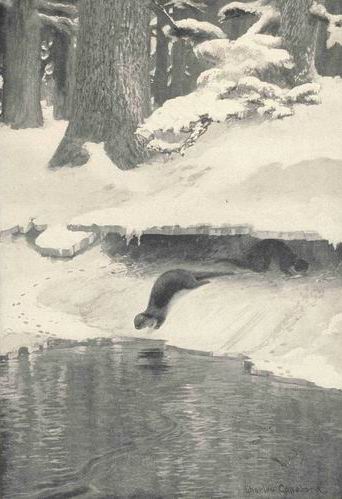

Years afterward, hundreds of miles away on the Dungarvon, in the heart

of the wilderness, every detail of the scene came back to me again. I

was standing on snowshoes, looking out over the frozen river, when

Keeonekh appeared in an open pool with a trout in his mouth. He broke

his way, with a clattering tinkle of winter bells, through the thin

edge of ice, put his paws against the heavy snow ice, threw himself out

with the same wriggling jump, and ate with his back arched —

just as I had seen him years before.

This curious way of eating is, I think, characteristic of all otters;

certainly of those that 1 have been fortunate enough to see. Why they

do it is more than I know; but it must be uncomfortable for every

mouthful — full of fish bones, too — to slide

uphill to one’s stomach. Perhaps it is mere habit, which

shows in the arched backs of all the weasel family. Perhaps it is to

frighten any enemy that may approach unawares while Keeonekh is eating,

just as an owl, when feeding on the ground, bristles up all his

feathers, so as to look big as possible.

But my first otter was too keen-scented to remain long so near a

concealed enemy. Suddenly he stopped eating and turned his head in my

direction. I could see his nostrils twitching as the wind gave him its

message. Then he left his fish, glided into the stream as noiselessly

as the brook entered it below him, and disappeared without leaving a

single wavelet to show where he had gone down.

When the young otters appeared, there was one of the most interesting

lessons to be seen in the woods. Though Keeonekh loves the water and

lives in it more than half the time, his little ones are afraid of it

as so many kittens. If left to themselves they would undoubtedly go off

for a hunting life, following the old family instinct; for fishing is

an acquired habit of the otters, and so the fishing instinct cannot yet

be transmitted to the little ones. That will take many generations.

Meanwhile the little Keeonekhs must be taught to swim.

One day the mother-otter appeared on the bank, among the roots of the

great tree under which was her secret doorway. That was surprising, for

up to this time both otters had always approached it from the river,

and were never seen on the bank near their den. She appeared to be

digging, but was immensely cautious about it, looking, listening,

sniffing continually. I had never gone near the place for fear of

frightening them away; and it was months afterward, when the den was

deserted, before I examined it to understand just what she was doing.

Then I found that she had made another doorway from her den, leading

out to the bank. She had selected the spot with wonderful

cunning,—a hollow under a great root that would never be

noticed, — and she dug from inside, carrying the earth down

to the river bottom, so that there should be nothing about the tree to

indicate the haunt of an animal.

WITH

BACK HUMPED AGAINST THE ICE ABOVE HIM, EATING HIS CATCH

Long afterward, when I had grown better acquainted with

Keeonekh’s ways from much watching, I understood the meaning

of all this. She was simply making a safe way out and in for the little

ones, who were afraid of the water. Had she taken or driven them out of

her own entrance under the river, they might easily have drowned ere

they reached the surface.

When the entrance was all ready she disappeared; but I have no doubt

she was just inside, watching to be sure the coast was clear. Slowly

her head and neck appeared till they showed clear of the black roots.

She turned her nose up stream — nothing in the wind. Eyes and

ears searched below — nothing harmful there. Then she came

out, and after her toddled two little otters, full of wonder at the big

bright world, full of fear at the river.

There was no play at first, only wonder and investigation. Caution was

born in them; they put their little feet down as if treading on eggs,

and they sniffed every bush before going behind it. And the old mother

noted their cunning with satisfaction, while her own nose and ears

watched far away.

The outing was all too short; some uneasiness was in the air down

stream. Suddenly she rose from where she was lying, and the little

ones, as if commanded, tumbled back into the den. In a moment she had

glided after them, and the bank was deserted. It was fully ten minutes

before my untrained ears caught faint sounds, which were not of the

woods, coming up stream; and longer than that before two men with fish

poles appeared, making their slow way to the pond above. They passed

almost over the den and disappeared, all unconscious of beast or man

that wished them elsewhere, resenting their noisy passage through the

solitudes. But the otters did not come out again, though I watched till

nearly dark.

It was a week before I saw them again, and some good teaching had

evidently been done in the meantime; for all fear of the river was

gone. They toddled out as before, at the same hour in the afternoon,

and went straight to the bank. There the mother lay down, and the

little ones, as if enjoying the frolic, clambered up to her back.

Whereupon she slid into the stream and swam slowly about with the

little Keeonekhs clinging to her desperately, as if humpty-dumpty had

been played on them before, and might be repeated any moment.

I understood their air of anxious expectation a moment later, when

Mother Otter dived like a flash from under them, leaving them to make

their own way in the water. They began to swim naturally enough, but

the fear of the new element was still upon them. The moment old Mother

Otter appeared they made for her, whimpering; but she dived again and

again, or moved slowly away, and so kept them swimming. After a little

they seemed to tire and lose courage. Her eyes saw it quicker than

mine, and she glided between them. Both little ones turned in at the

same instant and found a resting place on her back. So she brought them

carefully to land again, and in a few moments they were all rolling

about in the dry leaves like so many puppies.

The den in the river bank was never disturbed, and the following year

another litter was raised there. With characteristic cunning

— a cunning which grows keener and keener in the neighborhood

of civilization —the mother-otter filled up the land entrance

among the roots with earth and driftweed, using only the doorway under

water until it was time for the cubs to come out into the world again.

Of all the creatures of the wilderness Keeonekh is the most richly

gifted, and his ways, could we but search them out, would furnish a

most interesting chapter. Every journey he takes, whether by land or

water, is full of unknown traits and tricks; but unfortunately no one

ever sees him doing things, and most of his ways are yet to be found

out. You see a head holding swiftly across a wilderness lake, or coming

to meet your canoe on the streams; then, as you follow eagerly, a swirl

and he is gone. When he comes up again he will watch you so much more

keenly than you can possibly watch him that you learn little about him,

except how shy he is. Even the trappers who make a business of catching

him, and with whom I have often talked, know almost nothing of

Keeonekh, except where to set their traps for him living and how to

care for his skin when he is dead.

Once I saw him fishing in a curious way. It was winter, on a wilderness

stream flowing into the Dungarvon. There had been a fall of dry snow

that still lay deep and powdery over all the woods, too light to settle

or crust. At every step one had to lift a shovelful of the stuff on the

point of his snowshoe; and I was tired out, following some caribou that

wandered like plover in the rain.

Just below me was a deep open pool surrounded by double fringes of ice.

Early in the winter, while the stream was higher, the white ice had

formed thickly on the river wherever the current was not too swift for

freezing. Then the stream fell, and a shelf of new black ice formed at

the water’s level, eighteen inches or more below the first

ice, some of which still clung to the banks, reaching out in places two

or three feet and forming dark caverns with the ice below. Both shelves

dipped towards the water, forming a gentle incline all about the edges

of the open places.

A string of silver bubbles shooting across the black pool at my feet

roused me out of a drowsy weariness. There it was again, a rippling

wave across the pool, which rose to the surface a moment later in a

hundred bubbles, tinkling like tiny bells as they broke in the keen

air. Two or three times I saw it with growing wonder. Then something

stirred under the shelf of ice across the pool. An otter slid into the

water; the rippling wave shot across again; the bubbles broke at the

surface; and I knew that he was sitting under the white ice below me,

not twenty feet away.

A whole family of otters, three or four of them, were fishing there at

my feet in utter unconsciousness. Every little while the bubbles would

shoot across from my side and, watching sharply, I would see Keeonekh

slide out upon the lower shelf of ice, on the other side, and crouch

there in the gloom, with back humped against the ice above him, eating

his catch. The fish they caught were all small, evidently, for after a

few minutes he would throw himself flat on the ice, slide down the

incline into the water, making no splash or disturbance as he entered,

and the string of bubbles would shoot across to my side again.

For a full hour I watched

them breathlessly, marveling at their skill. A small fish is nimble

game to follow and catch in his own element. But at every slide

Keeonekh did it. Sometimes the rippling wave would shoot all over the

pool, and the bubbles break in a wild tangle, as the fish darted and

doubled below, with the otter after him. But it always ended the same

way. Keeonekh would slide out upon the ice shelf, and hump his back,

and begin to eat almost before the last bubble had tinkled behind him.

Curiously enough, the rule of the salmon fishermen prevailed here in

the wilderness: no two rods shall whip the same pool at the same time.

I would see an otter lying ready on the ice, evidently waiting for the

chase to end. Then, as another otter slid out beside him with his fish,

in he would go like a flash and take his turn. For a while the pool was

a lively place; the bubbles had no rest. Then the plunges grew fewer

and fewer, and the otters all disappeared into the ice caverns.

What became of them I could not make out; and I was too chilled to

watch longer. Above and below the pool the stream was frozen for a

distance; then there was more open water and more fishing. Whether they

followed along the bank under cover of the ice to other pools, or

simply slept where they were till hungry again, I never found out.

Certainly they had taken up their abode in an ideal spot, and would not

leave it willingly. The open pools gave excellent fishing, and the

upper ice shelf protected them perfectly from all enemies.

Once, a week later, I left the caribou and came back to the spot to

watch awhile; but the place was deserted. The black water gurgled and

dimpled across the pool, and slipped away silently under the lower edge

of ice, undisturbed by strings of silver bubbles. The ice caverns were

all dark and silent. The mink had stolen the fish heads, and there was

no trace anywhere to show that it was Keeonekh’s banquet hail.

The swimming power of an otter, which was so evident there in the

winter pool, is one of the most remarkable things in nature. All other

animals and birds, and even the best modeled of modern boats, leave

more or less wake behind them when moving through the water. But

Keeonekh leaves no more trail than a fish. This is partly because he

keeps his body well submerged when swimming, partly because of the

strong, deep, even stroke that drives him forward. Sometimes I have

wondered if the outer hairs of his coat — the waterproof

covering that keeps his fur dry, no matter how long he swims

— are not better oiled than in other animals; which might

account for the lack of ripple. I have seen him go down suddenly and

leave absolutely no break in the surface to show where he was. When

sliding also, plunging down a twenty-foot clay bank, he enters the

water with an astonishing lack of noise or disturbance of any kind.

In swimming at the surface he seems to use all four feet, like other

animals. But below the surface, when chasing fish, he uses only the

fore paws. The hind legs then stretch straight out behind and are used,

with the heavy tail, for a great rudder. By this means he turns and

doubles like a flash, following surely the swift dartings of frightened

trout, and beating them by sheer speed and nimbleness.

When fishing a pool he always hunts outward from the center, driving

the fish towards the bank, keeping himself within their circlings, and

so having the immense advantage of the shorter line in heading off his

game. The fish are seized as they crouch against the bank for

protection, or try to dart out past him. Large fish are frequently

caught from behind, as they lie resting in their spring-holes. So swift

and noiseless is his approach that they are seized before they become

aware of danger.

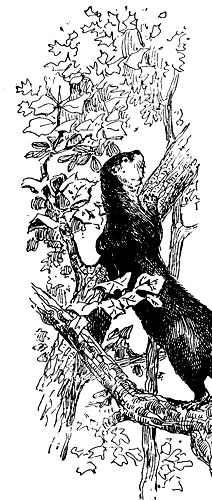

This swimming power of Keeonekh is all the more astonishing when one

remembers that he is a land animal, with none of the special endowments

of the seal, who is his only rival as a fisherman. Nature undoubtedly

intended him to get his living, as the other members of his large

family do, by hunting in the woods, and endowed him accordingly. He is

a strong runner, a good climber, a patient, tireless hunter, and his

nose is keen as a brier. With a little practice he could again get his

living by hunting, as his ancestors did. If squirrels and rats and

rabbits were too nimble at first, there are plenty of musquash to be

caught, and he need not stop at a fawn or a sheep; for he is enormously

strong, and the grip of his jaws is not to be loosened.

In severe winters, when fish are scarce or his pools frozen over, he

takes to the woods boldly and shows himself a master at hunting craft.

But he likes fish, and likes the water, and for many generations now

has been simply a fisherman, with many of the quiet, lovable traits

that belong to fishermen in general.

That is one thing to give you instant sympathy for Keeonekh —

he is so different, so far above all other members of his tribe. He is

very gentle by nature, with no trace of the fisher’s ferocity

or the weasel’s blood-thirstiness. He tames easily, and makes

the most docile and affectionate pet of all the wood folk. He never

kills for the sake of killing, but lives peaceably, so far as he can,

with all creatures. And he stops fishing when he has caught his dinner.

He is also most cleanly in his habits, with no suggestion whatever of

the evil odors that cling to the mink and defile the whole neighborhood

of a skunk. One cannot help wondering whether just going fishing has

not wrought all this wonder in Keeonekh’s disposition. If so,

‘t is a pity that all his tribe do not turn fishermen.

His one enemy among the wood folk, so far as I have observed, is the

beaver. As the latter is also a peaceable animal, it is difficult to

account for the hostility. I have heard or read somewhere that Keeonekh

is fond of young beaver and hunts them occasionally to vary his diet of

fish; but I have never found any evidence in the wilderness to show

this. Instead, I think it is simply a matter of the beaver’s

dam and pond that causes the trouble.

When the dam is built the beavers often dig a channel around either end

to carry off the surplus water, and so prevent their handiwork being

washed away in a freshet. Then the beavers guard their preserve

jealously, driving away the wood folk that dare to cross their dam or

enter their ponds, especially the musquash, who is apt to burrow and

cause them no end of trouble. But Keeonekh, secure in his strength,

holds straight through the pond, minding his own business and even

taking a fish ‘or two in the deep places near the dam. He

delights also in running water, especially in winter when lakes and

streams are mostly frozen, and in his journeyings he makes use of the

open channels that guard the beavers’ work. But the moment

the beavers hear a splashing there, or note a disturbance in the pond

where Keeonekh is chasing fish, down they come full of wrath. And there

is generally a desperate fight before the affair is settled.

Once, on a little pond, I saw a fierce battle going on out in the

middle, and paddled hastily to find out about it. Two beavers and a big

otter were locked in a death struggle, diving, plunging, throwing

themselves out of water, and snapping at each other’s throats.

As

my canoe halted, the otter gripped one of his antagonists and went

under with him. There was a terrible commotion below the surface for a

few moments. When it ended the beaver rolled up dead, and Keeonekh shot

up under the second beaver to repeat the attack. They gripped on the

instant, but the second beaver, an enormous fellow, refused to go

under, where he would be at a disadvantage. In my eagerness I let the

canoe drift almost upon them, driving them wildly apart before the

common danger. The otter held on his way up the lake; the beaver turned

towards the shore, where I noticed for the first time a couple of

beaver houses.

In this case there was no chance for intrusion on Keeonekh’s

part. He had probably been attacked when going peaceably about his

business through the lake.

It is barely possible, however, that there was an old grievance on the

beavers’ part, which they sought to square when they caught

Keeonekh on the lake. When beavers build their houses on the lake

shore, without the necessity for making a dam, they generally build a

tunnel slanting up from the lake’s bed to their den or house

on the bank. Now Keeonekh fishes under the ice in winter more than is

generally supposed. As he must breathe after every chase, he must needs

know all the air-holes and dens in the whole lake. No matter how much

he turns and doubles in the chase after a trout, he never loses his

sense of direction, never forgets where the breathing places are. When

his fish is seized he makes a bee line under the ice for the nearest

place where he can breathe and eat. Sometimes this lands him, out of

breath, in the beaver’s tunnel; and the beaver must sit

upstairs in his own house, nursing his wrath, while Keeonekh eats fish

in his hallway; for there is not room for both at once in the tunnel,

and a fight there or under the ice is out of the question. As the

beaver eats only bark the white inner layer of

“popple” bark is his chief dainty — he

cannot understand and cannot tolerate this barbarian, who eats raw

fish, and leaves the bones and fins and the smell of slime in his

doorway. The beaver is exemplary in his neatness, detesting all smells

and filth; and this may possibly account for some of his enmity and his

savage attacks upon Keeonekh when he catches him in a good place.

Not the least interesting of Keeonekh’s queer ways is his

habit of sliding down hill, which makes a bond of sympathy and brings

him close to the boyhood memories of those who know him.

I remember one pair of otters that I watched, for the better part of a

sunny afternoon, sliding down a clay bank with endless delight. The

slide had been made, with much care evidently, on the steep side of a

little promontory that jutted into the river. It was very steep, about

twenty feet high, and had been made perfectly smooth by much sliding

and wetting-down. An otter would appear at the top of the bank, throw

himself forward on his belly and shoot downward like a flash, diving

deep under water and reappearing some distance out from the foot of the

slide. And all this with marvelous stillness, as if the very woods had

ears and were listening to betray the shy creatures at their fun. For

it was fun, pure and simple, and fun with no end of tingle and

excitement in it, especially when one tried to catch the other and shot

into the water at his very heels.

This slide was in perfect condition, and the otters were careful not to

roughen it. They never scrambled up over it, but went round the point

and climbed from the other side; or else went up parallel to the slide,

some distance away, where the ascent was easier and where there was no

danger of rolling stones or sticks upon the coasting ground to spoil

its smoothness.

In winter the snow makes better coasting than the clay. Moreover it

soon grows hard and icy from the freezing of the water left by the

otter’s body, and after a few days the slide is as smooth as

glass. Then coasting is perfect, and every otter, old and young, has

his favorite slide and spends part of every pleasant day enjoying the

fun.

When traveling through the woods in deep snow, Keeonekh makes use of

his sliding habit to help him along, especially on down grades. He runs

a little way and throws himself forward on his belly, sliding through

the snow for several feet before he runs again. So his progress is a

series of slides, much as one hurries along in slippery weather.

I have spoken of the silver bubbles that first drew my attention to the

fishing otters, one day in the wilderness. From the few rare

opportunities that I have had to watch them, I think that the bubbles

are seen only after Keeonekh slides swiftly into the stream. The air

clings to the hairs of his rough outer coat and is brushed from them as

he passes through the water. One who watches him thus, shooting down

the long slide belly-bump into the black winter pool, with a string of

silver bubbles breaking and tinkling above him, is apt to know the

hunter’s change of heart from the touch of Nature which makes

us all kin. Thereafter he eschews trapping — at least you

will not find his number-three trap at the foot of Keeonekh’s

slide any more, to turn the shy creature’s happiness into

tragedy — and he sends a hearty good-luck after his

fellow-fisherman, whether he meet him on the wilderness lakes or in the

quiet places on the home streams, where nobody ever comes

|