| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Myths & Legends: The Celtic Race Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

VII: THE VOYAGE OF MAELDŪN Besides the legends which cluster round great

heroic names, and have, or at least pretend to have, the character of history,

there are many others, great and small, which tell of adventures lying purely

in regions of romance, and out of earthly space and time. As a specimen of

these I give here a summary of the “Voyage of Maeldūn,” a most curious and brilliant

piece of invention, which is found in the manuscript entitled the “Book of the

Dun Cow” (about 1100) and other early sources, and edited, with a translation

(to which I owe the following extracts), by Dr. Whitley Stokes in the “Revue Celtique”

for 1888 and 1889. It is only one of a number of such wonder-voyages found in

ancient Irish literature, but it is believed to have been the earliest of them

all and model for the rest, and it has had the distinction, in the abridged and

modified form given by Joyce in his “Old Celtic Romances,” of having furnished

the theme for the “Voyage of Maeldune” to Tennyson, who made it into a

wonderful creation of rhythm and colour, embodying a kind of allegory of Irish

history. It will be noticed at the end that we are in the unusual position of

knowing the name of the author of this piece of primitive literature, though he

does not claim to have composed, but only to have “put in order,” the incidents

of the “Voyage.” Unfortunately we cannot tell when he lived, but the tale as we

have it probably dates from the ninth century. Its atmosphere is entirely

Christian, and it has no mythological significance except in so far as it

teaches the lesson that the oracular injunctions of wizards should be obeyed.

No adventure, or even detail, of importance is omitted in the following summary

of the story, which is given thus fully because the reader may take it as

representing a large and important section of Irish legendary romance. Apart

from the source to which I am indebted, the “Revue Celtique,” I know no other

faithful reproduction in English of this wonderful tale. The

“Voyage of Maeldūn” begins, as Irish tales often do, by telling us of the

conception of its hero. There

was a famous man of the sept of the Owens of Aran, named Ailill Edge-of-Battle,

who went with his king on a foray into another territory. They encamped one

night near a church and convent of nuns. At midnight Ailill, who was near the

church, saw a certain nun come out to strike the bell for nocturns, and caught

her by the hand. In ancient Ireland religious persons were not much respected

in time of war, and Ailill did not respect her. When they parted, she said to

him: “Whence is thy race, and what is thy name?” Said the hero: “Ailill of the

Edge-of-Battle is my name, and I am of the Owenacht of Aran, in Thomond.” Not

long afterwards Ailill was slain by reavers from Leix, who burned the church of

Doocloone over his head. In

due time a son was born to the woman and she called his name Maeldūn. He was

taken secretly to her friend, the queen of the territory, and by her Maeldūn

was reared. “Beautiful indeed was his form, and it is doubtful if there hath

been in flesh any one so beautiful as he. So he grew up till he was a young

warrior and fit to use weapons. Great, then, was his brightness and his gaiety

and his playfulness. In his play he outwent all his comrades in throwing balls,

and in running and leaping and putting stones and racing horses.” One

day a proud young warrior who had been defeated by him taunted him with his

lack of knowledge of his kindred and descent. Maeldūn went to his foster-mother,

the queen, and said: “I will not eat nor drink till thou tell me who are my

mother and my father.” “I am thy mother,” said the queen, “for none ever loved

her son more than I love thee.” But Maeldūn insisted on knowing all, and the

queen at last took him to his own mother, the nun, who told him: “Thy father

was Ailill of the Owens of Aran.” Then Maeldūn went to his own kindred, and was

well received by them; and with him he took as guests his three beloved

foster-brothers, sons of the king and queen who had brought him up. After

a time Maeldūn happened to be among a company of young warriors who were

contending at putting the stone in the graveyard of the ruined church of

Doocloone. Maeldūn’s foot was planted, as he heaved the stone, on a scorched

and blackened flagstone; and one who was by, a monk named Briccne,1

said to him: “It were better for thee to avenge the man who was burnt there

than to cast stones over his burnt bones.”

“Who

was that?” asked Maeldūn. “Ailill,

thy father,” they told him. “Who

slew him?” said he. “Reavers

from Leix,” they said, “and they destroyed him on this spot.” Then

Maeldūn threw down the stone he was about to cast, and put his mantle round him

and went home; and he asked the way to Leix. They told him he could only go

there by sea.2 At

the advice of a Druid he then built him a boat, or coracle, of skins lapped

threefold one over the other; and the wizard also told him that seventeen men

only must accompany him, and on what day he must begin the boat and on what day

he must put out to sea. So

when his company was ready he put out and hoisted the sail, but had gone only a

little way when his three foster-brothers came down to the beach and entreated

him to take them. “Get you home,” said Maeldūn, “for none but the number I have

may go with me.” But the three youths would not be separated from Maeldūn, and

they flung themselves into the sea. He turned back, lest they should be

drowned, and brought them into his boat. All, as we shall see, were punished

for this transgression, and Maeldūn condemned to wandering until expiation had

been made. Irish

bardic tales excel in their openings. In this case, as usual, the mise-en-scène

is admirably contrived. The narrative which follows tells how, after seeing his

father’s slayer on an island, but being unable to land there, Maeldūn and his

party are blown out to sea, where they visit a great number of islands and have

many strange adventures on them. The tale becomes, in fact, a cento of

stories and incidents, some not very interesting, while in others, as in the

adventure of the Island of the Silver Pillar, or the Island of the Flaming

Rampart, or that where the episode of the eagle takes place, the Celtic sense

of beauty, romance, and mystery find an expression unsurpassed, perhaps, in

literature. In

the following rendering I have omitted the verses given by Joyce at the end of

each adventure. They merely recapitulate the prose narrative, and are not found

in the earliest manuscript authorities. The Island of the Slaves

Maeldūn

and his crew had rowed all day and half the night when they came to two small

bare islands with two forts in them, and a noise was heard from them of armed

men quarrelling. “Stand off from me,” cried one of them, “for I am a better man

than thou. ’Twas I slew Ailill of the Edge-of-Battle and burned the church of

Doocloone over him, and no kinsman has avenged his death on me. And thou

hast never done the like of that.” Then

Maeldūn was about to land, and Germān3 and Diuran the Rhymer cried

that God had guided them to the spot where they would be. But a great wind

arose suddenly and blew them off into the boundless ocean, and Maeldūn said to

his foster-brothers: “Ye have caused this to be, casting yourselves on board in

spite of the words of the Druid.” And they had no answer, save only to be

silent for a little space. The Island of the Ants

They

drifted three days and three nights, not knowing whither to row, when at the

dawn of the third day they heard the noise of breakers, and came to an island

as soon as the sun was up. Here, ere they could land, they met a swarm of

ferocious ants, each the size of a foal, that came down the strand and into the

sea to get at them; so they made off quickly, and saw no land for three days

more. The Island of the Great Birds

This

was a terraced island, with trees all round it, and great birds sitting on the

trees. Maeldūn landed first alone, and carefully searched the island for any

evil thing, but finding none, the rest followed him, and killed and ate many of

the birds, bringing others on board their boat.

The Island of the Fierce Beast

A

great sandy island was this, and on it a beast like a horse, but with clawed

feet like a hound’s. He flew at them to devour them, but they put off in time,

and were pelted by the beast with pebbles from the shore as they rowed away. The Island of the Giant Horses

A

great, flat island, which it fell by lot to Germān and Diuran to explore first.

They found a vast green racecourse, on which were the marks of horses’ hoofs,

each as big as the sail of a ship, and the shells of nuts of monstrous size

were lying about, and much plunder. So they were afraid, and took ship hastily

again, and from the sea they saw a horse-race in progress and heard the

shouting of a great multitude cheering on the white horse or the brown, and saw

the giant horses running swifter than the wind.4 So they rowed away

with all their might, thinking they had come upon an assembly of demons. The Island of the Stone Door

A

full week passed, and then they found a great, high island with a house standing

on the shore. A door with a valve of stone opened into the sea, and through it

the sea-waves kept hurling salmon into the house. Maeldūn and his party

entered, and found the house empty of folk, but a great bed lay ready for the

chief to whom it belonged, and a bed for each three of his company, and meat

and drink beside each bed. Maeldūn and his party ate and drank their fill, and

then sailed off again. The Island of the Apples

By

the time they had come here they had been a long time voyaging, and food had

failed them, and they were hungry. This island had precipitous sides from which

a wood hung down, and as they passed along the cliffs Maeldūn broke off a twig

and held it in his hand. Three days and nights they coasted the cliff and found

no entrance to the island, but by that time a cluster of three apples had grown

on the end of Maeldūn’s rod, and each apple sufficed the crew for forty days. The Island of the Wondrous Beast

This

island had a fence of stone round it, and within the fence a huge beast that

raced round and round the island. And anon it went to the top of the island,

and then performed a marvellous feat, viz., it turned its body round and round

inside its skin, the skin remaining unmoved, while again it would revolve its

skin round and round the body. When it saw the party it rushed at them, but

they escaped, pelted with stones as they rowed away. One of the stones pierced

through Maeldūn’s shield and lodged in the keel of the boat. The Island of the Biting Horses

Here

were many great beasts resembling horses, that tore continually pieces of flesh

from each other’s sides, so that all the island ran with blood. They rowed

hastily away, and were now disheartened and full of complaints, for they knew

not where they were, nor how to find guidance or aid in their quest. The Island of the Fiery Swine

With

great weariness, hunger, and thirst they arrived at the tenth island, which was

full of trees loaded with golden apples. Under the trees went red beasts, like

fiery swine, that kicked the trees with their legs, when the apples fell and

the beasts consumed them. The beasts came out at morning only, when a multitude

of birds left the island, and swam out to sea till nones, when they turned and

swam inward again till vespers, and ate the apples all night. Maeldūn

and his comrades landed at night, and felt the soil hot under their feet from

the fiery swine in their caverns underground. They collected all the apples

they could, which were good both against hunger and thirst, and loaded their

boat with them and put to sea once more, refreshed. The Island of the Little Cat

The

apples had failed them when they came hungry and thirsting to the eleventh

island. This was, as it were, a tall white tower of chalk reaching up to the

clouds, and on the rampart about it were great houses white as snow. They

entered the largest of them, and found no man in it, but a small cat playing on

four stone pillars which were in the midst of the house, leaping from one to

the other. It looked a little on the Irish warriors, but did not cease from its

play. On the walls of the houses there were three rows of objects hanging up,

one row of brooches of gold and silver, and one of neck-torques of gold and

silver, each as big as the hoop of a cask, and one of great swords with gold

and silver hilts. Quilts and shining garments lay in the room, and there, also,

were a roasted ox and a flitch of bacon and abundance of liquor. “Hath this

been left for us?” said Maeldūn to the cat. It looked at him a moment, and then

continued its play. So there they ate and drank and slept, and stored up what

remained of the food. Next day, as they made to leave the house, the youngest

of Maeldūn’s foster-brothers took a necklace from the wall, and was bearing it

out when the cat suddenly “leaped through him like a fiery arrow,” and he fell,

a heap of ashes, on the floor. Thereupon Maeldūn, who had forbidden the theft

of the jewel, soothed the cat and replaced the necklace, and they strewed the

ashes of the dead youth on the sea-shore, and put to sea again. The Island of the Black and the

White Sheep

This

had a brazen palisade dividing it in two, and a flock of black sheep on one

side and of white sheep on the other. Between them was a big man who tended the

flocks, and sometimes he put a white sheep among the black, when it became black

at once, or a black sheep among the white, when it immediately turned white.5

By way of an experiment Maeldūn flung a peeled white wand on the side of the

black sheep. It at once turned black, whereat they left the place in terror,

and without landing. The Island of the Giant Cattle

A

great and wide island with a herd of huge swine on it. They killed a small pig

and roasted it on the spot, as it was too great to carry on board. The island

rose up into a very high mountain, and Diuran and Germān went to view the

country from the top of it. On their way they met a broad river. To try the

depth of the water Germān dipped in the haft of his spear, which at once was

consumed as with liquid fire. On the other bank was a huge man guarding what

seemed a herd of oxen. He called to them not to disturb the calves, so they

went no further and speedily sailed away.

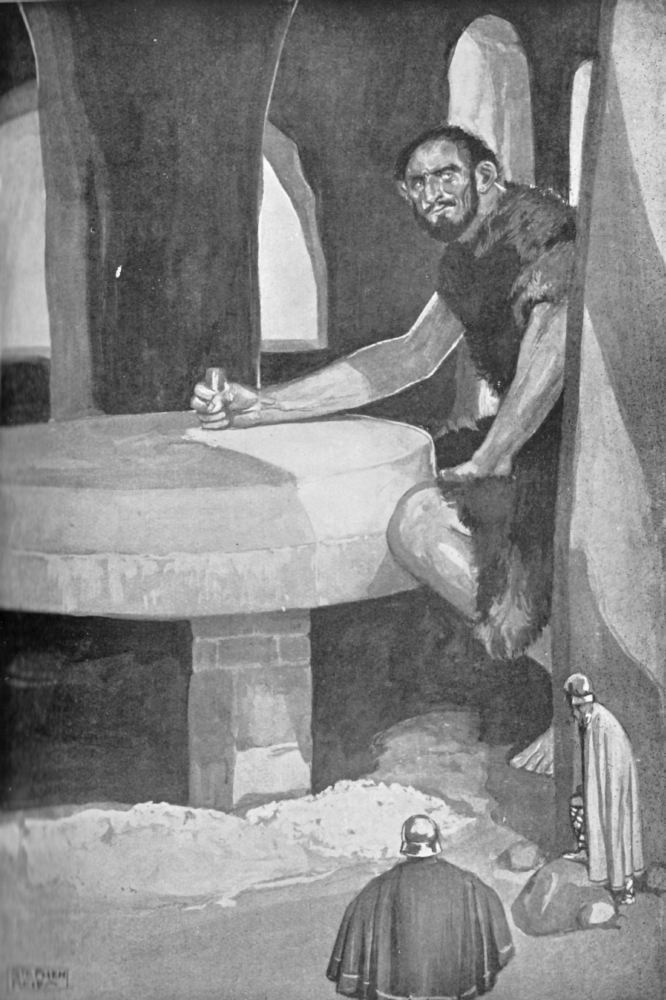

The Island of the Mill

Here

they found a great and grim-looking mill, and a giant miller grinding corn in

it. “Half the corn of your country,” he said, “is ground here. Here comes to be

ground all that men begrudge to each other.” Heavy and many were the loads they

saw going to it, and all that was ground in it was carried away westwards. So

they crossed themselves and sailed away.

The Island of the Black Mourners

An

island full of black people continually weeping and lamenting. One of the two

remaining foster-brothers landed on it, and immediately turned black and fell

to weeping like the rest. Two others went to fetch him; the same fate befell

them. Four others then went with their heads wrapped in cloths, that they

should not look on the land or breathe the air of the place, and they seized

two of the lost ones and brought them away perforce, but not the

foster-brother. The two rescued ones could not explain their conduct except by

saying that they had to do as they saw others doing about them. The Island of the Four Fences

Four

fences of gold, silver, brass, and crystal divided this island into four parts,

kings in one, queens in another, warriors in a third, maidens in the fourth. On

landing, a maiden gave them food like cheese, that tasted to each man as he

wished it to be, and an intoxicating liquor that put them asleep for three

days. When they awoke they were at sea in their boat, and of the island and its

inhabitants nothing was to be seen. The Island of the Glass Bridge

Here

we come to one of the most elaborately wrought and picturesque of all the

incidents of the voyage. The island they now reached had on it a fortress with

a brazen door, and a bridge of glass leading to it. When they sought to cross

the bridge it threw them backward.6 A woman came out of the fortress

with a pail in her hand, and lifting from the bridge a slab of glass she let

down her pail into the water beneath, and returned to the fortress. They struck

on the brazen portcullis before them to gain admittance, but the melody given

forth by the smitten metal plunged them in slumber till the morrow morn. Thrice

over this happened, the woman each time making an ironical speech about

Maeldūn. On the fourth day, however, she came out to them over the bridge,

wearing a white mantle with a circlet of gold on her hair, two silver sandals

on her rosy feet, and a filmy silken smock next her skin. “My

welcome to thee, O Maeldūn,” she said, and she welcomed each man of the crew by

his own name. Then she took them into the great house and allotted a couch to

the chief, and one for each three of his men. She gave them abundance of food

and drink, all out of her one pail, each man finding in it what he most

desired. When she had departed they asked Maeldūn if they should woo the maiden

for him. “How would it hurt you to speak with her?” says Maeldūn. They do so,

and she replies: “I know not, nor have ever known, what sin is.” Twice over

this is repeated. “To-morrow,” she says at last, “you shall have your answer.”

When the morning breaks, however, they find themselves once more at sea, with

no sign of the island or fortress or lady.

The Island of the Shouting Birds

They

hear from afar a great cry and chanting, as it were a singing of psalms, and

rowing for a day and night they come at last to an island full of birds, black,

brown, and speckled, all shouting and speaking. They sail away without landing. The Island of the Anchorite

Here

they found a wooded island full of birds, and on it a solitary man, whose only

clothing was his hair. They asked him of his country and kin. He tells them

that he was a man of Ireland who had put to sea7 with a sod of his

native country under his feet. God had turned the sod into an island, adding a

foot’s breadth to it and one tree for every year. The birds are his kith and

kin, and they all wait there till Doomsday, miraculously nourished by angels.

He entertained them for three nights, and then they sailed away. The Island of the Miraculous

Fountain

This

island had a golden rampart, and a soft white soil like down. In it they found

another anchorite clothed only in his hair. There was a fountain in it which

yields whey or water on Fridays and Wednesdays, milk on Sundays and feasts of

martyrs, and ale and wine on the feasts of Apostles, of Mary, of John the

Baptist, and on the high tides of the year.

The Island of the Smithy

As

they approached this they heard from afar as it were the clanging of a tremendous

smithy, and heard men talking of themselves. “Little boys they seem,” said one,

“in a little trough yonder.” They rowed hastily away, but did not turn their boat,

so as not to seem to be flying; but after a while a giant smith came out of the

forge holding in his tongs a huge mass of glowing iron, which he cast after

them, and all the sea boiled round it, as it fell astern of their boat. The Sea of Clear Glass

After

that they voyaged until they entered a sea that resembled green glass. Such was

its purity that the gravel and the sand of the sea were clearly visible through

it; and they saw no monsters or beasts therein among the crags, but only the

pure gravel and the green sand. For a long space of the day they were voyaging

in that sea, and great was its splendour and its beauty.8 The Undersea Island

They

next found themselves in a sea, thin like mist, that seemed as if it would not

support their boat. In the depths they saw roofed fortresses, and a fair land

around them. A monstrous beast lodged in a tree there, with droves of cattle

about it, and beneath it an armed warrior. In spite of the warrior, the beast

ever and anon stretched down a long neck and seized one of the cattle and

devoured it. Much dreading lest they should sink through that mist-like sea,

they sailed over it and away. The Island of the Prophecy

When

they arrived here they found the water rising in high cliffs round the island,

and, looking down, saw on it a crowd of people, who screamed at them, “It is

they, it is they,” till they were out of breath. Then came a woman and pelted

them from below with large nuts, which they gathered and took with them. As

they went they heard the folk crying to each other: “Where are they now?” “They

are gone away.” “They are not.” “It is likely,” says the tale, “that there was

some one concerning whom the islanders had a prophecy that he would ruin their

country and expel them from their land.” The Island of the Spouting Water

Here

a great stream spouted out of one side of the island and arched over it like a

rainbow, falling on the strand at the further side. And when they thrust their

spears into the stream above them they brought out salmon from it as much as

they would, and the island was filled with the stench of those they could not

carry away. The Island of the Silvern Column

The

next wonder to which they came forms one of the most striking and imaginative

episodes of the voyage. It was a great silvern column, four-square, rising from

the sea. Each of its four sides was as wide as two oar-strokes of the boat. Not

a sod of earth was at its foot, but it rose from the boundless ocean and its

summit was lost in the sky. From that summit a huge silver net was flung far

away into the sea, and through a mesh of that net they sailed. As they did so

Diuran hacked away a piece of the net. “Destroy it not,” said Maeldūn, “for

what we see is the work of mighty men.” Diuran said: “For the praise of God’s

name I do this, that our tale may be believed, and if I reach Ireland again

this piece of silver shall be offered by me on the high altar of Armagh.” Two

ounces and a half it weighed when it was measured afterwards in Armagh. “And

then they heard a voice from the summit of yonder pillar, mighty, clear, and

distinct. But they knew not the tongue it spake, or the words it uttered.” The Island of the Pedestal

The

next island stood on a foot, or pedestal, which rose from the sea, and they could

find no way of access to it. In the base of the pedestal was a door, closed and

locked, which they could not open, so they sailed away, having seen and spoken

with no one. The Island of the Women

Here

they found the rampart of a mighty dūn, enclosing a mansion. They landed to

look on it, and sat on a hillock near by. Within the dūn they saw seventeen

maidens busy at preparing a great bath. In a little while a rider, richly clad,

came up swiftly on a racehorse, and lighted down and went inside, one of the

girls taking the horse. The rider then went into the bath, when they saw that

it was a woman. Shortly after that one of the maidens came out and invited them

to enter, saying: “The Queen invites you.” They went into the fort and bathed,

and then sat down to meat, each man with a maiden over against him, and Maeldūn

opposite to the queen. And Maeldūn was wedded to the queen, and each of the

maidens to one of his men, and at nightfall canopied chambers were allotted to

each of them. On the morrow morn they made ready to depart, but the queen would

not have them go, and said: “Stay here, and old age will never fall on you, but

ye shall remain as ye are now for ever and ever, and what ye had last night ye

shall have always. And be no longer a-wandering from island to island on the

ocean.” She

then told Maeldūn that she was the mother of the seventeen girls they had seen,

and her husband had been king of the island. He was now dead, and she reigned

in his place. Each day she went into the great plain in the interior of the

island to judge the folk, and returned to the dūn at night. So

they remained there for three months of winter; but at the end of that time it

seemed they had been there three years, and the men wearied of it, and longed

to set forth for their own country. “What

shall we find there,” said Maeldūn, “that is better than this?” But

still the people murmured and complained, and at last they said: “Great is the

love which Maeldūn has for his woman. Let him stay with her alone if he will,

but we will go to our own country.” But Maeldūn would not be left after them,

and at last one day, when the queen was away judging the folk, they went on

board their bark and put out to sea. Before they had gone far, however, the

queen came riding up with a clew of twine in her hand, and she flung it after

them. Maeldūn caught it in his hand, and it clung to his hand so that he could

not free himself, and the queen, holding the other end, drew them back to land.

And they stayed on the island another three months. Twice

again the same thing happened, and at last the people averred that Maeldūn held

the clew on purpose, so great was his love for the woman. So the next time

another man caught the clew, but it clung to his hand as before; so Diuran

smote off his hand, and it fell with the clew into the sea. “When she saw that

she at once began to wail and shriek, so that all the land was one cry, wailing

and shrieking.” And thus they escaped from the Island of the Women. The Island of the Red Berries

On

this island were trees with great red berries which yielded an intoxicating and

slumbrous juice. They mingled it with water to moderate its power, and filled

their casks with it, and sailed away. The Island of the Eagle

A

large island, with woods of oak and yew on one side of it, and on the other a

plain, whereon were herds of sheep, and a little lake in it; and there also

they found a small church and a fort, and an ancient grey cleric, clad only in

his hair. Maeldūn asked him who he was. “I am

the fifteenth man of the monks of St. Brennan of Birr,” he said. “We went on

our pilgrimage into the ocean, and they have all died save me alone.” He showed

them the tablet (? calendar) of the Holy Brennan, and they prostrated

themselves before it, and Maeldūn kissed it. They stayed there for a season,

feeding on the sheep of the island. One

day they saw what seemed to be a cloud coming up from the south-west. As it

drew near, however, they saw the waving of pinions, and perceived that it was

an enormous bird. It came into the island, and, alighting very wearily on a

hill near the lake, it began eating the red berries, like grapes, which grew on

a huge tree-branch as big as a full-grown oak, that it had brought with it, and

the juice and fragments of the berries fell into the lake, reddening all the

water. Fearful that it would seize them in its talons and bear them out to sea,

they lay hid in the woods and watched it. After a while, however, Maeldūn went

out to the foot of the hill, but the bird did him no harm, and then the rest

followed cautiously behind their shields, and one of them gathered the berries

off the branch which the bird held in its talons, but it did them no evil, and

regarded them not at all. And they saw that it was very old, and its plumage

dull and decayed. At

the hour of noon two eagles came up from the south-west and alit in front of

the great bird, and after resting awhile they set to work picking off the

insects that infested its jaws and eyes and ears. This they continued till

vespers, when all three ate of the berries again. At last, on the following

day, when the great bird had been completely cleansed, it plunged into the

lake, and again the two eagles picked and cleansed it. Till the third day the

great bird remained preening and shaking its pinions, and its feathers became

glossy and abundant, and then, soaring upwards, it flew thrice round the

island, and away to the quarter whence it had come, and its flight was now

swift and strong; whence it was manifest to them that this had been its renewal

from old age to youth, according as the prophet said, Thy youth is renewed

like the eagle’s.9 Then

Diuran said: “Let us bathe in that lake and renew ourselves where the bird hath

been renewed.” “Nay,” said another, “for the bird hath left his venom in it.”

But Diuran plunged in and drank of the water. From that time so long as he

lived his eyes were strong and keen, and not a tooth fell from his jaw nor a

hair from his head, and he never knew illness or infirmity. Thereafter

they bade farewell to the anchorite, and fared forth on the ocean once more. The Island of the Laughing Folk

Here

they found a great company of men laughing and playing incessantly. They drew

lots as to who should enter and explore it, and it fell to Maeldūn’s

foster-brother. But when he set foot on it he at once began to laugh and play

with the others, and could not leave off, nor would he come back to his

comrades. So they left him and sailed away.10 The Island of the Flaming Rampart

They now

came in sight of an island which was not large, and it had about it a rampart

of flame that circled round and round it continually. In one part of the

rampart there was an opening, and when this opening came opposite to them they

saw through it the whole island, and saw those who dwelt therein, even men and

women, beautiful, many, and wearing adorned garments, with vessels of gold in

their hands. And the festal music which they made came to the ears of the

wanderers. For a long time they lingered there, watching this marvel, “and they

deemed it delightful to behold.” The Island of the Monk of Tory

Far

off among the waves they saw what they took to be a white bird on the water.

Drawing near to it they found it to be an aged man clad only in the white hair

of his body, and he was throwing himself in prostrations on a broad rock. “From

Torach11 I have come hither,” he said, “and there I was reared. I was

cook in the monastery there, and the food of the Church I used to sell for

myself, so that I had at last much treasure of raiment and brazen vessels and

gold-bound books and all that man desires. Great was my pride and arrogance. “One

day as I dug a grave in which to bury a churl who had been brought on to the

island, a voice came from below where a holy man lay buried, and he said: ‘Put

not the corpse of a sinner on me, a holy, pious person!’ ” After

a dispute the monk buried the corpse elsewhere, and was promised an eternal

reward for doing so. Not long thereafter he put to sea in a boat with all his

accumulated treasures, meaning apparently to escape from the island with his

plunder. A great wind blew him far out to sea, and when he was out of sight of

land the boat stood still in one place. He saw near him a man (angel) sitting

on the wave. “Whither goest thou?” said the man. “On a pleasant way, whither I

am now looking,” said the monk. “It would not be pleasant to thee if thou

knewest what is around thee,” said the man. “So far as eye can see there is one

crowd of demons all gathered around thee, because of thy covetousness and

pride, and theft, and other evil deeds. Thy boat hath stopped, nor will it move

until thou do my will, and the fires of hell shall get hold of thee.” He

came near to the boat, and laid his hand on the arm of the fugitive, who

promised to do his will. “Fling

into the sea,” he said, “all the wealth that is in thy boat.” “It

is a pity,” said the monk, “that it should go to loss.” “It

shall in nowise go to loss. There will be one man whom thou wilt profit.” The

monk thereupon flung everything into the sea save one little wooden cup, and he

cast away oars and rudder. The man gave him a provision of whey and seven

cakes, and bade him abide wherever his boat should stop. The wind and waves

carried him hither and thither till at last the boat came to rest upon the rock

where the wanderers found him. There was nothing there but the bare rock, but

remembering what he was bidden he stepped out upon a little ledge over which

the waves washed, and the boat immediately left him, and the rock was enlarged

for him. There he remained seven years, nourished by otters which brought him

salmon out of the sea, and even flaming firewood on which to cook them, and his

cup was filled with good liquor every day. “And neither wet nor heat nor cold

affects me in this place.” At

the noon hour miraculous nourishment was brought for the whole crew, and

thereafter the ancient man said to them:

“Ye

will all reach your country, and the man that slew thy father, O Maeldūn, ye

will find him in a fortress before you. And slay him not, but forgive him;

because God hath saved you from manifold great perils, and ye too are men

deserving of death.” Then

they bade him farewell and went on their accustomed way. The Island of the Falcon

This

is uninhabited save for herds of sheep and oxen. They land on it and eat their

fill, and one of them sees there a large falcon. “This falcon,” he says, “is

like the falcons of Ireland.” “Watch it,” says Maeldūn, “and see how it will go

from us.” It flew off to the south-east, and they rowed after it all day till

vespers. The Home-coming

At

nightfall they sighted a land like Ireland; and soon came to a small island,

where they ran their prow ashore. It was the island where dwelt the man who had

slain Ailill. They

went up to the dūn that was on the island, and heard men talking within it as

they sat at meat. One man said: “It

would be ill for us if we saw Maeldūn now.”

“That

Maeldūn has been drowned,” said another.

“Maybe

it is he who shall waken you from sleep to-night,” said a third. “If

he should come now,” said a fourth, “what should we do?” “Not

hard to answer that,” said the chief of them. “Great welcome should he have if

he were to come, for he hath been a long space in great tribulation.” Then

Maeldūn smote with the wooden clapper against the door. “Who is there?” asked

the doorkeeper. “Maeldūn

is here,” said he. They

entered the house in peace, and great welcome was made for them, and they were

arrayed in new garments. And then they told the story of all the marvels that

God had shown them, according to the words of the “sacred poet,” who said, Haec

olim meminisse juvabit.12 Then Maeldūn went to his own home

and kindred, and Diuran the Rhymer took with him the piece of silver that he had

hewn from the net of the pillar, and laid it on the high altar of Armagh in

triumph and exultation at the miracles that God had wrought for them. And they

told again the story of all that had befallen them, and all the marvels they

had seen by sea and land, and the perils they had endured. The

story ends with the following words: “Now

Aed the Fair [Aed Finn13], chief sage of Ireland, arranged this

story as it standeth here; and he did so for a delight to the mind, and for the

folks of Ireland after him.”  The Offering of Diuran the Rhymer 1 Here we have evidently a reminiscence of Briccriu of the

Poisoned Tongue, the mischief-maker of the Ultonians. 2 The Arans are three islands at the entrance of Galway Bay.

They are a perfect museum of mysterious ruins. 3 Pronounced “Ghermawn” — the “G” hard. 4 Horse-racing was a particular delight to the ancient Irish,

and is mentioned in a ninth-century poem

in praise of May as one of the

attractions of that month. The name of the month of May given in an ancient Gaulish calendar means “the month of

horse-racing.” 5 The same phenomenon is recorded as being witnessed by

Peredur in the Welsh tale of that name

in the “Mabinogion.” 6 Like the bridge to Skatha’s dūn, p. 188. 7 Probably we are to understand that he was an anchorite

seeking for an islet on which to dwell

in solitude and contemplation. The

western islands of Ireland abound in the ruins of huts and

oratories built by single monks or

little communities. 8 Tennyson has been particularly happy in his description of

these undersea islands. 9 Ps. ciii. 5. 10 This disposes of the last of the foster-brothers, who

should not have joined the party. 11 Tory Island, off the Donegal coast. There was there a

monastery and a church dedicated to St. Columba. 12 “One day we shall delight in the remembrance of these

things.” The quotation is from Vergil, “Æn.” i. 203 “Sacred poet” is a

translation of the vates sacer of Horace. 13 This sage and poet has not been identified from any other

record. Praise and thanks to him, whoever he may have been. |