| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Myths & Legends: The Celtic Race Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

VIII: MYTHS AND TALES OF THE CYMRY Bardic

Philosophy

The

absence in early Celtic literature of any world-myth, or any

philosophic

account of the origin and constitution of things, was noticed at the

opening of

our third chapter. In Gaelic literature there is, as far as I know,

nothing

which even pretends to represent early Celtic thought on this subject.

It is

otherwise in Wales. Here there has existed for a considerable time a

body of

teaching purporting to contain a portion, at any rate, of that ancient

Druidic

thought which, as Caesar tells us, was communicated only to the

initiated, and

never written down. This teaching is principally to be found in two

volumes

entitled “Barddas,” a compilation made from materials in his possession

by a

Welsh bard and scholar named Llewellyn Sion, of Glamorgan, towards the

end of

the sixteenth century, and edited, with a translation, by J.A. Williams

ap Ithel

for the Welsh MS. Society. Modern Celtic scholars pour contempt on the

pretensions of works like this to enshrine any really antique thought.

Thus Mr.

Ivor B. John: “All idea of a bardic esoteric doctrine involving

pre-Christian

mythic philosophy must be utterly discarded.” And again: “The nonsense

talked

upon the subject is largely due to the uncritical invention of

pseudo-antiquaries of the sixteenth to seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries.”1

Still the bardic Order was certainly at one time in possession of such

a

doctrine. That Order had a fairly continuous existence in Wales. And

though no

critical thinker would build with any confidence a theory of

pre-Christian

doctrine on a document of the sixteenth century, it does not seem wise

to scout

altogether the possibility that some fragments of antique lore may have

lingered even so late as that in bardic tradition.

At

any rate, “Barddas” is a work of considerable philosophic interest, and

even if

it represents nothing but a certain current of Cymric thought in the

sixteenth

century it is not unworthy of attention by the student of things

Celtic. Purely

Druidic it does not even profess to be, for Christian personages and

episodes

from Christian history figure largely in it. But we come occasionally

upon a

strain of thought which, whatever else it may be, is certainly not

Christian,

and speaks of an independent philosophic system. In

this system two primary existences are contemplated, God and Cythrawl,

who

stand respectively for the principle of energy tending towards life,

and the

principle of destruction tending towards nothingness. Cythrawl is

realised in

Annwn, which may be rendered, the Abyss, or Chaos. In the beginning

there was

nothing but God and Annwn.2 Organised life began by the Word

— God

pronounced His ineffable Name and the “Manred” was formed. The Manred

was the

primal substance of the universe. It was conceived as a multitude of

minute

indivisible particles — atoms, in fact — each being a microcosm, for

God is

complete in each of them, while at the same time each is a part of God,

the

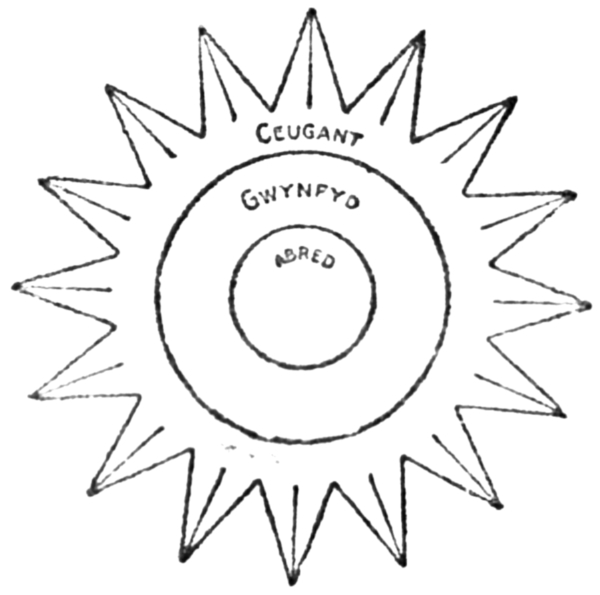

Whole. The totality of being as it now exists is represented by three

concentric circles. The innermost of them, where life sprang from

Annwn, is

called “Abred,” and is the stage of struggle and evolution — the

contest of

life with Cythrawl. The next is the circle of “Gwynfyd,” or Purity, in

which

life is manifested as a pure, rejoicing force, having attained its

triumph over

evil. The last and outermost circle is called “Ceugant,” or Infinity.

Here all

predicates fail us, and this circle, represented graphically not by a

bounding

line, but by divergent rays, is inhabited by God alone. The following

extract

from “Barddas,” in which the alleged bardic teaching is conveyed in

catechism form,

will serve to show the order of ideas in which the writer’s mind moved:

The

Circles of Being “Q.

Whence didst thou proceed? “A. I

came from the Great World, having my beginning in Annwn.

“Q.

Where art thou now? and how camest thou to what thou art?

“A. I

am in the Little World, whither I came having traversed the circle of

Abred,

and now I am a Man, at its termination and extreme limits.

“Q.

What wert thou before thou didst become a man, in the circle of Abred? “A. I

was in Annwn the least possible that was capable of life and the

nearest

possible to absolute death; and I came in every form and through every

form

capable of a body and life to the state of man along the circle of

Abred, where

my condition was severe and grievous during the age of ages, ever since

I was

parted in Annwn from the dead, by the gift of God, and His great

generosity,

and His unlimited and endless love. “Q.

Through how many different forms didst thou come, and what happened

unto thee?” “A.

Through every form capable of life, in water, in earth, in air. And

there

happened unto me every severity, every hardship, every evil, and every

suffering, and but little was the goodness or Gwynfyd before I became a

man....

Gwynfyd cannot be obtained without seeing and knowing everything, but

it is not

possible to see or to know everything without suffering everything....

And there

can be no full and perfect love that does not produce those things

which are

necessary to lead to the knowledge that causes Gwynfyd.”

Every

being, we are told, shall attain to the circle of Gwynfyd at last.3 There

is much here that reminds us of Gnostic or Oriental thought. It is

certainly

very unlike Christian orthodoxy of the sixteenth century. As a product

of the

Cymric mind of that period the reader may take it for what it is worth,

without

troubling himself either with antiquarian theories or with their

refutations. Let

us now turn to the really ancient work, which is not philosophic, but

creative

and imaginative, produced by British bards and fabulists of the Middle

Ages.

But before we go on to set forth what we shall find in this literature

we must

delay a moment to discuss one thing which we shall not.

The

Arthurian Saga

For

the majority of modern readers who have not made any special study of

the

subject, the mention of early British legend will inevitably call up

the

glories of the Arthurian Saga — they will think of the fabled palace at

Caerleon-on-Usk,

the Knights of the Round Table riding forth on chivalrous adventure,

the Quest

of the Grail, the guilty love of Lancelot, flower of knighthood, for

the queen,

the last great battle by the northern sea, the voyage of Arthur, sorely

wounded, but immortal, to the mystic valley of Avalon. But as a matter

of fact

they will find in the native literature of mediæval Wales little or

nothing of

all this — no Round Table, no Lancelot, no Grail-Quest, no Isle of

Avalon,

until the Welsh learned about them from abroad; and though there was

indeed an

Arthur in this literature, he is a wholly different being from the

Arthur of

what we now call the Arthurian Saga. Nennius

The

earliest extant mention of Arthur is to be found in the work of the

British

historian Nennius, who wrote his “Historia Britonum” about the year

800. He

derives his authority from various sources — ancient monuments and

writings of

Britain and of Ireland (in connexion with the latter country he records

the

legend of Partholan), Roman annals, and chronicles of saints,

especially St.

Germanus. He presents a fantastically Romanised and Christianised view

of

British history, deriving the Britons from a Trojan and Roman ancestry.

His

account of Arthur, however, is both sober and brief. Arthur, who,

according to

Nennius, lived in the sixth century, was not a king; his ancestry was

less

noble than that of many other British chiefs, who, nevertheless, for

his great

talents as a military Imperator, or dux bellorum, chose

him for

their leader against the Saxons, whom he defeated in twelve battles,

the last

being at Mount Badon. Arthur’s office was doubtless a relic of Roman

military

organisation, and there is no reason to doubt his historical existence,

however

impenetrable may be the veil which now obscures his valiant and often

triumphant battlings for order and civilisation in that disastrous age. Geoffrey of

Monmouth

Next

we have Geoffrey of Monmouth, Bishop of St. Asaph, who wrote his

“Historia

Regum Britaniæ” in South Wales in the early part of the twelfth

century. This

work is an audacious attempt to make sober history out of a mass of

mythical or

legendary matter mainly derived, if we are to believe the author, from

an ancient

book brought by his uncle Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, from Brittany.

The

mention of Brittany in this connexion is, as we shall see, very

significant.

Geoffrey wrote expressly to commemorate the exploits of Arthur, who now

appears

as a king, son of Uther Pendragon and of Igerna, wife of Gorlois, Duke

of

Cornwall, to whom Uther gained access in the shape of her husband

through the

magic arts of Merlin. He places the beginning of Arthur’s reign in the

year

505, recounts his wars against the Saxons, and says he ultimately

conquered not

only all Britain, but Ireland, Norway, Gaul, and Dacia, and

successfully

resisted a demand for tribute and homage from the Romans. He held his

court at Caerleon-on-Usk.

While he was away on the Continent carrying on his struggle with Rome

his

nephew Modred usurped his crown and wedded his wife Guanhumara. Arthur,

on

this, returned, and after defeating the traitor at Winchester slew him

in a

last battle in Cornwall, where Arthur himself was sorely wounded (A.D.

542).

The queen retired to a convent at Caerleon. Before his death Arthur

conferred

his kingdom on his kinsman Constantine, and was then carried off

mysteriously

to “the isle of Avalon” to be cured, and “the rest is silence.”

Arthur’s magic

sword “Caliburn” (Welsh Caladvwlch; see p. 224, note) is

mentioned by

Geoffrey and described as having been made in Avalon, a word which

seems to

imply some kind of fairyland, a Land of the Dead, and may be related to

the

Norse Valhall. It was not until later times that Avalon came to

be

identified with an actual site in Britain (Glastonbury). In Geoffrey’s

narrative there is nothing about the Holy Grail, or Lancelot, or the

Round

Table, and except for the allusion to Avalon the mystical element of

the

Arthurian saga is absent. Like Nennius, Geoffrey finds a fantastic

classical

origin for the Britons. His so-called history is perfectly worthless as

a

record of fact, but it has proved a veritable mine for poets and

chroniclers,

and has the distinction of having furnished the subject for the

earliest

English tragic drama, “Gorboduc,” as well as for Shakespeare’s “King

Lear”; and

its author may be described as the father — at least on its

quasi-historical side

— of the Arthurian saga, which he made up partly out of records of the

historical

dux bellorum of Nennius and partly out of poetical

amplifications of

these records made in Brittany by the descendants of exiles from Wales,

many of

whom fled there at the very time when Arthur was waging his wars

against the

heathen Saxons. Geoffrey’s book had a wonderful success. It was

speedily

translated into French by Wace, who wrote “Li Romans de Brut” about

1155, with

added details from Breton sources, and translated from Wace’s French

into

Anglo-Saxon by Layamon, who thus anticipated Malory’s adaptations of

late

French prose romances. Except a few scholars who protested

unavailingly, no one

doubted its strict historical truth, and it had the important effect of

giving

to early British history a new dignity in the estimation of Continental

and of

English princes. To sit upon the throne of Arthur was regarded as in

itself a

glory by Plantagenet monarchs who had not a trace of Arthur’s or of any

British

blood. The Saga in

Brittany: Marie de

France

The

Breton sources must next be considered. Unfortunately, not a line of

ancient

Breton literature has come down to us, and for our knowledge of it we

must rely

on the appearances it makes in the work of French writers. One of the

earliest

of these is the Anglo-Norman poetess who called herself Marie de

France, and

who wrote about 1150 and afterwards. She wrote, among other things, a

number of

“Lais,” or tales, which she explicitly and repeatedly tells us were

translated

or adapted from Breton sources. Sometimes she claims to have rendered a

writer’s original exactly: “Les contes

que jo sai verais Dunt li Bretun unt

fait les lais Vos conterai assez

briefment; Et cief [sauf] di

cest coumencement Selunc la lettre è

l’escriture.” Little

is actually said about Arthur in these tales, but the events of them

are placed

in his time — en cel tems tint Artus la terre — and the

allusions, which

include a mention of the Round Table, evidently imply a general

knowledge of

the subject among those to whom these Breton “Lais” were addressed.

Lancelot is

not mentioned, but there is a “Lai” about one Lanval, who is beloved by

Arthur’s queen, but rejects her because he has a fairy mistress in the

“isle

d’Avalon.” Gawain is mentioned, and an episode is told in the “Lai de

Chevrefoil” about Tristan and Iseult, whose maid, “Brangien,” is

referred to in

a way which assumes that the audience knew the part she had played on

Iseult’s

bridal night. In short, we have evidence here of the existence in

Brittany of a

well-diffused and well-developed body of chivalric legend gathered

about the

personality of Arthur. The legends are so well known that mere

allusions to

characters and episodes in them are as well understood as references to

Tennyson’s “Idylls” would be among us to-day. The “Lais” of Marie de

France

therefore point strongly to Brittany as the true cradle of the

Arthurian saga,

on its chivalrous and romantic side. They do not, however, mention the

Grail. Chrestien de

Troyes

Lastly,

and chiefly, we have the work of the French poet Chrestien de Troyes,

who began

in 1165 to translate Breton “Lais,” like Marie de France, and who

practically

brought the Arthurian saga into the poetic literature of Europe, and

gave it

its main outline and character. He wrote a “Tristan” (now lost). He (if

not

Walter Map) introduced Lancelot of the Lake into the story; he wrote a Conte

del Graal, in which the Grail legend and Perceval make their first

appearance, though he left the story unfinished, and does not tell us

what the

“Grail” really was.4 He also wrote a long conte

d’aventure

entitled “Erec,” containing the story of Geraint and Enid. These are

the

earliest poems we possess in which the Arthur of chivalric legend comes

prominently forward. What were the sources of Chrestien? No doubt they

were largely

Breton. Troyes is in Champagne, which had been united to Blois in 1019

by

Eudes, Count of Blois, and reunited again after a period of

dispossession by

Count Theobald de Blois in 1128. Marie, Countess of Champagne, was

Chrestien’s patroness.

And there were close connexions between the ruling princes of Blois and

of

Brittany. Alain II., a Duke of Brittany, had in the tenth century

married a

sister of the Count de Blois, and in the first quarter of the

thirteenth

century Jean I. of Brittany married Blanche de Champagne, while their

daughter

Alix married Jean de Chastillon, Count of Blois, in 1254. It is highly

probable, therefore, that through minstrels who attended their Breton

lords at

the court of Blois, from the middle of the tenth century onward, a

great many

Breton “Lais” and legends found their way into French literature during

the

eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries. But it is also certain

that the

Breton legends themselves had been strongly affected by French

influences, and

that to the Matière de France, as it was called by mediæval

writers5

— i.e., the legends of Charlemagne

and his Paladins — we owe the Table Round and the chivalric

institutions

ascribed to Arthur’s court at Caerleon-on-Usk.

Bleheris

It

must not be forgotten that (as Miss Jessie L. Weston has emphasised in

her

invaluable studies on the Arthurian saga) Gautier de Denain, the

earliest of

the continuators or re-workers of Chrestien de Troyes, mentions as his

authority for stories of Gawain one Bleheris, a poet “born and bred in

Wales.”

This forgotten bard is believed to be identical with famosus ille

fabulator,

Bledhericus, mentioned by Giraldus Cambrensis, and with the Bréris

quoted

by Thomas of Brittany as an authority for the Tristan story. Conclusion

as to the Origin of the

Arthurian Saga

In

the absence, however, of any information as to when, or exactly what,

Bleheris

wrote, the opinion must, I think, hold the field that the Arthurian

saga, as we

have it now, is not of Welsh, nor even of pure Breton origin. The Welsh

exiles

who colonised part of Brittany about the sixth century must have

brought with

them many stories of the historical Arthur. They must also have brought

legends

of the Celtic deity Artaius, a god to whom altars have been found in

France.

These personages ultimately blended into one, even as in Ireland the

Christian

St. Brigit blended with the pagan goddess Brigindo.6 We thus

get a

mythical figure combining something of the exaltation of a god with a

definite

habitation on earth and a place in history. An Arthur saga thus arose,

which in

its Breton (though not its Welsh) form was greatly enriched by material

drawn

in from the legends of Charlemagne and his peers, while both in

Brittany and in

Wales it became a centre round which clustered a mass of floating

legendary

matter relating to various Celtic personages, human and divine.

Chrestien de

Troyes, working on Breton material, ultimately gave it the form in

which it

conquered the world, and in which it became in the twelfth and the

thirteenth

centuries what the Faust legend was in later times, the accepted

vehicle for

the ideals and aspirations of an epoch. The Saga in

Wales

From

the Continent, and especially from Brittany, the story of Arthur came

back into

Wales transformed and glorified. The late Dr. Heinrich Zimmer, in one

of his

luminous studies of the subject, remarks that “In Welsh literature we

have

definite evidence that the South-Welsh prince, Rhys ap Tewdwr, who had

been in

Brittany, brought from thence in the year 1070 the knowledge of

Arthur’s Round

Table to Wales, where of course it had been hitherto unknown.”7

And

many Breton lords are known to have followed the banner of William the

Conqueror into England.8 The introducers of the saga into

Wales

found, however, a considerable body of Arthurian matter of a very

different

character already in existence there. Besides the traditions of the

historical

Arthur, the dux bellorum of Nennius, there was the Celtic

deity,

Artaius. It is probably a reminiscence of this deity whom we meet with

under

the name of Arthur in the only genuine Welsh Arthurian story we

possess, the

story of Kilhwch and Olwen in the “Mabinogion.” Much of the Arthurian

saga

derived from Chrestien and other Continental writers was translated and

adapted

in Wales as in other European countries, but as a matter of fact it

made a

later and a lesser impression in Wales than almost anywhere else. It

conflicted

with existing Welsh traditions, both historical and mythological; it

was full

of matter entirely foreign to the Welsh spirit, and it remained always

in Wales

something alien and unassimilated. Into Ireland it never entered at all. These

few introductory remarks do not, of course, profess to contain a

discussion of

the Arthurian saga — a vast subject with myriad ramifications,

historical,

mythological, mystical, and what not — but are merely intended to

indicate the

relation of that saga to genuine Celtic literature and to explain why

we shall

hear so little of it in the following accounts of Cymric myths and

legends. It

was a great spiritual myth which, arising from the composite source

above

described, overran all the Continent, as its hero was supposed to have

done in

armed conquest, but it cannot be regarded as a special possession of

the Celtic

race, nor is it at present extant, except in the form of translation or

adaptation, in any Celtic tongue. Gaelic and

Cymric Legend Compared

The

myths and legends of the Celtic race which have come down to us in the

Welsh

language are in some respects of a different character from those which

we

possess in Gaelic. The Welsh material is nothing like as full as the

Gaelic,

nor so early. The tales of the “Mabinogion” are mainly drawn from the

fourteenth-century manuscript entitled “The Red Book of Hergest.” One

of them,

the romance of Taliesin, came from another source, a manuscript of the

seventeenth century. The four oldest tales in the “Mabinogion” are

supposed by

scholars to have taken their present shape in the tenth or eleventh

century,

while several Irish tales, like the story of Etain and Midir or the

Death of

Conary, go back to the seventh or eighth. It will be remembered that

the story

of the invasion of Partholan was known to Nennius, who wrote about the

year

800. As one might therefore expect, the mythological elements in the

Welsh

romances are usually much more confused and harder to decipher than in

the

earlier of the Irish tales. The mythic interest has grown less, the

story

interest greater; the object of the bard is less to hand down a sacred

text

than to entertain a prince’s court. We must remember also that the

influence of

the Continental romances of chivalry is clearly perceptible in the

Welsh tales;

and, in fact, comes eventually to govern them completely.

Gaelic and

Continental Romance

In

many respects the Irish Celt anticipated the ideas of these romances.

The lofty

courtesy shown to each other by enemies,9 the fantastic

pride which

forbade a warrior to take advantage of a wounded adversary,10

the

extreme punctilio with which the duties or observances proper to each

man’s

caste or station were observed11 — all this tone of thought

and

feeling which would seem so strange to us if we met an instance of it

in

classical literature would seem quite familiar and natural in

Continental

romances of the twelfth and later centuries. Centuries earlier than

that it was

a marked feature in Gaelic literature. Yet in the Irish romances,

whether

Ultonian or Ossianic, the element which has since been considered the

most

essential motive in a romantic tale is almost entirely lacking. This is

the

element of love, or rather of woman-worship. The Continental fabulist

felt that

he could do nothing without this motive of action. But the “lady-love”

of the

English, French, or German knight, whose favour he wore, for whose

grace he

endured infinite hardship and peril, does not meet us in Gaelic

literature. It would

have seemed absurd to the Irish Celt to make the plot of a serious

story hinge

on the kind of passion with which the mediaeval Dulcinea inspired her

faithful

knight. In the two most famous and popular of Gaelic love-tales, the

tale of

Deirdre and “The Pursuit of Dermot and Grania,” the women are the

wooers, and

the men are most reluctant to commit what they know to be the folly of

yielding

to them. Now this romantic, chivalric kind of love, which idealised

woman into

a goddess, and made the service of his lady a sacred duty to the

knight, though

it never reached in Wales the height which it did in Continental and

English romances,

is yet clearly discernible there. We can trace it in “Kilhwch and

Olwen,” which

is comparatively an ancient tale. It is well developed in later stories

like

“Peredur” and “The Lady of the Fountain.” It is a symptom of the extent

to

which, in comparison with the Irish, Welsh literature had lost its pure

Celtic

strain and become affected — I do not, of course, say to its loss — by

foreign

influences. Gaelic and

Cymric Mythology: Nudd

The

oldest of the Welsh tales, those called “The Four Branches of the

Mabinogi,”12

are the richest in mythological elements, but these occur in more or

less

recognisable form throughout nearly all the mediaeval tales, and even,

after

many transmutations, in Malory. We can clearly discern certain

mythological

figures common to all Celtica. We meet, for instance, a personage

called Nudd

or Lludd, evidently a solar deity. A temple dating from Roman times,

and

dedicated to him under the name of Nodens, has been discovered at

Lydney, by

the Severn. On a bronze plaque found near the spot is a representation

of the

god. He is encircled by a halo and accompanied by flying spirits and by

Tritons. We are reminded of the Danaan deities and their close

connexion with

the sea; and when we find that in Welsh legend an epithet is attached

to Nudd,

meaning “of the Silver Hand” (though no extant Welsh legend tells the

meaning

of the epithet), we have no difficulty in identifying this Nudd with

Nuada of

the Silver Hand, who led the Danaans in the battle of Moytura.13

Under his name Lludd he is said to have had a temple on the site of St.

Paul’s

in London, the entrance to which, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth,

was called

in the British tongue Parth Lludd, which the Saxons translated Ludes

Geat, our present Ludgate. Llyr and Manawyddan

Again,

when we find a mythological personage named Llyr, with a son named

Manawyddan,

playing a prominent part in Welsh legend, we may safely connect them

with the

Irish Lir and his son Mananan, gods of the sea. Llyr-cester, now

Leicester, was

a centre of the worship of Llyr. Llew Llaw

Gyffes

Finally,

we may point to a character in the “Mabinogi,” or tale, entitled “Māth

Son of

Māthonwy.” The name of this character is given as Llew Llaw Gyffes,

which the Welsh

fabulist interprets as “The Lion of the Sure Hand,” and a tale, which

we shall

recount later on, is told to account for the name. But when we find

that this

hero exhibits characteristics which point to his being a solar deity,

such as

an amazingly rapid growth from childhood into manhood, and when we are

told,

moreover, by Professor Rhys that Gyffes originally meant, not “steady”

or

“sure,” but “long,”14 it becomes evident that we have here a

dim and

broken reminiscence of the deity whom the Gaels called Lugh of the Long

Arm,15

Lugh Lamh Fada. The misunderstood name survived, and round

the

misunderstanding legendary matter floating in the popular mind

crystallised

itself in a new story.    These

correspondences might be pursued in much further detail. It is enough

here to

point to their existence as evidence of the original community of

Gaelic and

Cymric mythology.16 We are, in each literature, in the same

circle

of mythological ideas. In Wales, however, these ideas are harder to

discern;

the figures and their relationships in the Welsh Olympus are less

accurately

defined and more fluctuating. It would seem as if a number of different

tribes

embodied what were fundamentally the same conceptions under different

names and

wove different legends about them. The bardic literature, as we have it

now,

bears evidence sometimes of the prominence of one of these tribal

cults,

sometimes of another. To reduce these varying accounts to unity is

altogether

impossible. Still, we can do something to afford the reader a clue to

the maze. The Houses

of Dōn and of Llyr

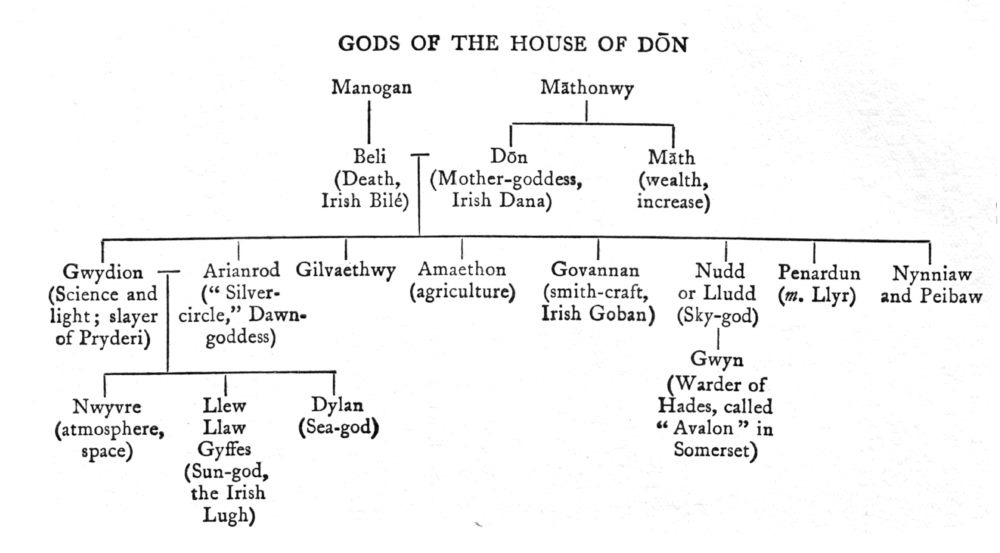

Two

great divine houses or families are discernible — that of Dōn, a

mother-goddess

(representing the Gaelic Dana), whose husband is Beli, the Irish Bilé,

god of

Death, and whose descendants are the Children of Light; and the House

of Llyr,

the Gaelic Lir, who here represents, not a Danaan deity, but something

more

like the Irish Fomorians. As in the case of the Irish myth, the two

families

are allied by intermarriage — Penardun, a daughter of Dōn, is wedded to

Llyr.

Dōn herself has a brother, Māth, whose name signifies wealth or

treasure (cf.

Greek Pluton, ploutos), and they descend from a figure

indistinctly

characterised, called Māthonwy. The House of

Arthur

Into

the pantheon of deities represented in the four ancient Mabinogi there

came, at

a later time, from some other tribal source, another group headed by

Arthur,

the god Artaius. He takes the place of Gwydion son of Dōn, and the

other

deities of his circle fall more or less accurately into the places of

others of

the earlier circle. The accompanying genealogical plans are intended to

help

the reader to a general view of the relationships and attributes of

these

personages. It must be borne in mind, however, that these tabular

arrangements

necessarily involve an appearance of precision and consistency which is

not

reflected in the fluctuating character of the actual myths taken as a

whole.

Still, as a sketch-map of a very intricate and obscure region, they may

help

the reader who enters it for the first time to find his bearings in it,

and that

is the only purpose they propose to serve.

Gwyn ap Nudd

The

deity named Gwyn ap Nudd is said, like Finn in Gaelic legend,17

to have

impressed himself more deeply and lastingly on the Welsh popular

imagination

than any of the other divinities. A mighty warrior and huntsman, he

glories in

the crash of breaking spears, and, like Odin, assembles the souls of

dead

heroes in his shadowy kingdom, for although he belongs to the kindred

of the

Light-gods, Hades is his special domain. The combat between him and

Gwythur ap

Greidawl (Victor, son of Scorcher) for Creudylad, daughter of Lludd,

which is

to be renewed every May-day till time shall end, represents evidently

the

contest between winter and summer for the flowery and fertile earth.

“Later,”

writes Mr. Charles Squire, “he came to be considered as King of the Tylwyth

Teg, the Welsh fairies, and his name as such has hardly yet died

out of his

last haunt, the romantic vale of Neath.... He is the Wild Huntsman of

Wales and

the West of England, and it is his pack which is sometimes heard at

chase in

waste places by night.”18 He figures as a god of war and

death in a

wonderful poem from the “Black Book of Caermarthen,” where he is

represented as

discoursing with a prince named Gwyddneu Garanhir, who had come to ask

his protection.

I quote a few stanzas: the poem will be found in full in Mr. Squire’s

excellent

volume: “I come from

battle and conflict With a shield in my

hand; Broken is my

helmet by the thrusting of spears. “Round-hoofed

is my horse, the torment of battle, Fairy am I called,19

Gwyn the son of Nudd, The lover of

Crewrdilad, the daughter of Lludd “I have been

in the place where Gwendolen was slain, The son of Ceidaw,

the pillar of song, Where the ravens

screamed over blood. “I have been

in the place where Bran was killed, The son of Iweridd,

of far-extending fame, Where the ravens of

the battlefield screamed. “I have been

where Llacheu was slain, The son of Arthur,

extolled in songs, When the ravens

screamed over blood. “I have been

where Mewrig was killed, The son of Carreian,

of honourable fame, When the ravens

screamed over flesh. “I have been

where Gwallawg was killed, The son of Goholeth,

the accomplished, The resister of

Lloegyr,20 the son of Lleynawg. “I have been

where the soldiers of Britain were slain, From the east to the

north: I am the

escort of the grave. “I have been

where the soldiers of Britain were slain, From the east to the

south: I am alive,

they in death.”

Myrddin, or

Merlin

A

deity named Myrddin holds in Arthur’s mythological cycle the place of

the Sky-

and Sun-god, Nudd. One of the Welsh Triads tells us that Britain,

before it was

inhabited, was called Clas Myrddin, Myrddin’s Enclosure. One is

reminded

of the Irish fashion of calling any favoured spot a “cattle-fold of the

sun” — the

name is applied by Deirdre to her beloved Scottish home in Glen Etive.

Professor Rhys suggests that Myrddin was the deity specially worshipped

at

Stonehenge, which, according to British tradition as reported by

Geoffrey of

Monmouth, was erected by “Merlin,” the enchanter who represents the

form into

which Myrddin had dwindled under Christian influences. We are told that

the

abode of Merlin was a house of glass, or a bush of whitethorn laden

with bloom,

or a sort of smoke or mist in the air, or “a close neither of iron nor

steel

nor timber nor of stone, but of the air without any other thing, by

enchantment

so strong that it may never be undone while the world endureth.”21

Finally he descended upon Bardsey Island, “off the extreme westernmost

point of

Carnarvonshire ... into it he went with nine attendant bards, taking

with him

the ’Thirteen Treasures of Britain,’ thenceforth lost to men.”

Professor Rhys

points out that a Greek traveller named Demetrius, who is described as

having

visited Britain in the first century A.D., mentions an island in the

west where

“Kronos” was supposed to be imprisoned with his attendant deities, and

Briareus

keeping watch over him as he slept, “for sleep was the bond forged for

him.”

Doubtless we have here a version, Hellenised as was the wont of

classical

writers on barbaric myths, of a British story of the descent of the

Sun-god

into the western sea, and his imprisonment there by the powers of

darkness,

with the possessions and magical potencies belonging to Light and Life.22 Nynniaw and

Peibaw

The

two personages called Nynniaw and Peibaw who figure in the genealogical

table

play a very slight part in Cymric mythology, but one story in which

they appear

is interesting in itself and has an excellent moral. They are

represented23

as two brothers, Kings of Britain, who were walking together one

starlight

night. “See what a fine far-spreading field I have,” said Nynniaw.

“Where is

it?” asked Peibaw. “There aloft and as far as you can see,” said

Nynniaw,

pointing to the sky. “But look at all my cattle grazing in your field,”

said

Peibaw. “Where are they?” said Nynniaw. “All the golden stars,” said

Peibaw,

“with the moon for their shepherd.” “They shall not graze on my field,”

cried

Nynniaw. “I say they shall,” returned Peibaw. “They shall not.” “They

shall.”

And so they went on: first they quarrelled with each other, and then

went to

war, and armies were destroyed and lands laid waste, till at last the

two

brothers were turned into oxen as a punishment for their stupidity and

quarrelsomeness. The

“Mabinogion”

We

now come to the work in which the chief treasures of Cymric myth and

legend

were collected by Lady Charlotte Guest sixty years ago, and given to

the world

in a translation which is one of the masterpieces of English

literature. The

title of this work, the “Mabinogion,” is the plural form of the word Mabinogi,

which means a story belonging to the equipment of an

apprentice-bard, such

a story as every bard had necessarily to learn as part of his training,

whatever more he might afterwards add to his répertoire.

Strictly

speaking, the Mabinogi in the volume are only the four tales

given first

in Mr. Alfred Nutt’s edition, which were entitled the “Four Branches of

the

Mabinogi,” and which form a connected whole. They are among the oldest

relics

of Welsh mythological saga. Pwyll, Head

of Hades

The

first of them is the story of Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, and relates how

that

prince got his title of Pen Annwn, or “Head of Hades” — Annwn

being the

term under which we identify in Welsh literature the Celtic Land of the

Dead,

or Fairyland. It is a story with a mythological basis, but breathing

the purest

spirit of chivalric honour and nobility.

Pwyll,

it is said, was hunting one day in the woods of Glyn Cuch when he saw a

pack of

hounds, not his own, running down a stag. These hounds were snow-white

in

colour, with red ears. If Pwyll had had any experience in these matters

he

would have known at once what kind of hunt was up, for these are the

colours of

Faëry — the red-haired man, the red-eared hound are always associated

with

magic.24 Pwyll, however, drove off the strange hounds, and

was

setting his own on the quarry when a horseman of noble appearance came

up and

reproached him for his discourtesy. Pwyll offered to make amends, and

the story

now develops into the familiar theme of the Rescue of Fairyland. The

stranger’s

name is Arawn, a king in Annwn. He is being harried and dispossessed by

a

rival, Havgan, and he seeks the aid of Pwyll, whom he begs to meet

Havgan in

single combat a year hence. Meanwhile he will put his own shape on

Pwyll, who

is to rule in his kingdom till the eventful day, while Arawn will go in

Pwyll’s

shape to govern Dyfed. He instructs Pwyll how to deal with the foe.

Havgan must

be laid low with a single stroke — if another is given to him he

immediately revives

again as strong as ever. Pwyll

agreed to follow up the adventure, and accordingly went in Arawn’s

shape to the

kingdom of Annwn. Here he was placed in an unforeseen difficulty. The

beautiful

wife of Arawn greeted him as her husband. But when the time came for

them to

retire to rest he set his face to the wall and said no word to her, nor

touched

her at all until the morning broke. Then they rose up, and Pwyll went

to the

hunt, and ruled his kingdom, and did all things as if he were monarch

of the

land. And whatever affection he showed to the queen in public during

the day,

he passed every night even as this first.

At

last the day of battle came, and, like the chieftains in Gaelic story,

Pwyll

and Havgan met each other in the midst of a river-ford. They fought,

and at the

first clash Havgan was hurled a spear’s length over the crupper of his

horse

and fell mortally wounded.25 “For the love of heaven,” said

he,

“slay me and complete thy work.” “I may yet repent that,” said Pwyll.

“Slay

thee who may, I will not.” Then Havgan knew that his end was come, and

bade his

nobles bear him off; and Pwyll with all his army overran the two

kingdoms of

Annwn, and made himself master of all the land, and took homage from

its

princes and lords. Then

he rode off alone to keep his tryst in Glyn Cuch with Arawn as they had

appointed. Arawn thanked him for all he had done, and added: “When thou

comest

thyself to thine own dominions thou wilt see what I have done for

thee.” They

exchanged shapes once more, and each rode in his own likeness to take

possession of his own land. At

the court of Annwn the day was spent in joy and feasting, though none

but Arawn

himself knew that anything unusual had taken place. When night came

Arawn

kissed and caressed his wife as of old, and she pondered much as to

what might

be the cause of his change towards her, and of his previous change a

year and a

day before. And as she was thinking over these things Arawn spoke to

her twice

or thrice, but got no answer. He then asked her why she was silent. “I

tell

thee,” she said, “that for a year I have not spoken so much in this

place.”

“Did not we speak continually?” he said. “Nay,” said she, “but for a

year back

there has been neither converse nor tenderness between us.” “Good

heaven!”

thought Arawn, “a man as faithful and firm in his friendship as any

have I

found for a friend.” Then he told his queen what had passed. “Thou hast

indeed laid

hold of a faithful friend,” she said. And

Pwyll when he came back to his own land called his lords together and

asked

them how they thought he had sped in his kingship during the past year.

“Lord,”

said they, “thy wisdom was never so great, and thou wast never so kind

and free

in bestowing thy gifts, and thy justice was never more worthily seen

than in

this year.” Pwyll then told them the story of his adventure. “Verily,

lord,”

said they, “render thanks unto heaven that thou hast such a fellowship,

and

withhold not from us the rule which we have enjoyed for this year

past.” “I

take heaven to witness that I will not withhold it,” said Pwyll. So

the two kings made strong the friendship that was between them, and

sent each

other rich gifts of horses and hounds and jewels; and in memory of the

adventure Pwyll bore thenceforward the title of “Lord of Annwn.” The Wedding

of Pwyll and Rhiannon

Near

to the castle of Narberth, where Pwyll had his court, there was a mound

called

the Mound of Arberth, of which it was believed that whoever sat upon it

would

have a strange adventure: either he would receive blows and wounds or

he would

see a wonder. One day when all his lords were assembled at Narberth for

a feast

Pwyll declared that he would sit on the mound and see what would befall. He

did so, and after a little while saw approaching him along the road

that led to

the mound a lady clad in garments that shone like gold, and sitting on

a pure

white horse. “Is there any among you,” said Pwyll to his men, “who

knows that

lady?” “There is not,” said they. “Then go to meet her and learn who

she is.”

But as they rode towards the lady she moved away from them, and however

fast

they rode she still kept an even distance between her and them, yet

never

seemed to exceed the quiet pace with which she had first approached. Several

times did Pwyll seek to have the lady overtaken and questioned, but all

was in

vain — none could draw near to her. Next

day Pwyll ascended the mound again, and once more the fair lady on her

white

steed drew near. This time Pwyll himself pursued her, but she flitted

away

before him as she had done before his servants, till at last he cried :

“O

maiden, for the sake of him thou best lovest, stay for me.” “I will

stay

gladly,” said she, “and it were better for thy horse had thou asked it

long

since.” Pwyll

then questioned her as to the cause of her coming, and she said: “I am

Rhiannon, the daughter of Hevydd Hēn,26 and they sought to

give me to

a husband against my will. But no husband would I have, and that

because of my

love for thee; neither will I yet have one if thou reject me.” “By

heaven!”

said Pwyll, “if I might choose among all the ladies and damsels of the

world,

thee would I choose.”  The Penance of Rhiannon They

then agree that in a twelvemonth from that day Pwyll is to come and

claim her

at the palace of Hevydd Hēn. Pwyll

kept his tryst, with a following of a hundred knights, and found a

splendid

feast prepared for him, and he sat by his lady, with her father on the

other

side. As they feasted and talked there entered a tall, auburn-haired

youth of royal

bearing, clad in satin, who saluted Pwyll and his knights. Pwyll

invited him to

sit down. “Nay, I am a suitor to thee,” said the youth; “to crave a

boon am I

come.” “Whatever thou wilt thou shalt have,” said Pwyll unsuspiciously,

“if it

be in my power.” “Ah,” cried Rhiannon, “wherefore didst thou give that

answer?”

“Hath he not given it before all these nobles?” said the youth; “and

now the

boon I crave is to have thy bride Rhiannon, and the feast and the

banquet that are

in this place.” Pwyll was silent. “Be silent as long as thou wilt,”

said

Rhiannon. “Never did man make worse use of his wits than thou hast

done.” She

tells him that the auburn-haired young man is Gwawl, son of Clud, and

is the

suitor to escape from whom she had fled to Pwyll. Pwyll

is bound in honour by his word, and Rhiannon explains that the banquet

cannot

be given to Gwawl, for it is not in Pwyll’s power, but that she herself

will be

his bride in a twelvemonth; Gwawl is to come and claim her then, and a

new

bridal feast will be prepared for him. Meantime she concerts a plan

with Pwyll,

and gives him a certain magical bag, which he is to make use of when

the time

shall come. A

year passed away, Gwawl appeared according to the compact, and a great

feast

was again set forth, in which he, and not Pwyll, had the place of

honour. As

the company were making merry, however, a beggar clad in rags and shod

with

clumsy old shoes came into the hall, carrying a bag, as beggars are

wont to do.

He humbly craved a boon of Gwawl. It was merely that the full of his

bag of

food might be given him from the banquet. Gwawl cheerfully consented,

and an

attendant went to fill the bag. But however much they put into it, it

never got

fuller — by degrees all the good things on the tables had gone in; and

at last

Gwawl cried: “My soul, will thy bag never be full?” “It will not, I

declare to

heaven,” answered Pwyll — for he, of course, was the disguised beggar

man — “unless

some man wealthy in lands and treasure shall get into the bag and stamp

it down

with his feet, and declare, ‘Enough has been put herein.’ ” Rhiannon

urged Gwawl

to check the voracity of the bag. He put his two feet into it; Pwyll

immediately

drew up the sides of the bag over Gwawl’s head and tied it up. Then he

blew his

horn, and the knights he had with him, who were concealed outside,

rushed in,

and captured and bound the followers of Gwawl. “What is in the bag?”

they

cried, and others answered, “A badger,” and so they played the game of

“Badger

in the Bag,” striking it and kicking it about the hall.

At

last a voice was heard from it. “Lord,” cried Gwawl, “if thou wouldst

but hear

me, I merit not to be slain in a bag.” “He speaks truth,” said Hevydd

Hēn. So an

agreement was come to that Gwawl should provide means for Pwyll to

satisfy all

the suitors and minstrels who should come to the wedding, and abandon

Rhiannon,

and never seek to have revenge for what had been done to him. This was

confirmed by sureties, and Gwawl and his men were released and went to

their

own territory. And Pwyll wedded Rhiannon, and dispensed gifts royally

to all

and sundry; and at last the pair, when the feasting was done, journeyed

down to

the palace of Narberth in Dyfed, where Rhiannon gave rich gifts, a

bracelet and

a ring or a precious stone to all the lords and ladies of her new

country, and

they ruled the land in peace both that year and the next. But the

reader will

find that we have not yet done with Gwawl.

The Penance

of Rhiannon

Now

Pwyll was still without an heir to the throne, and his nobles urged him

to take

another wife. “Grant us a year longer,” said he, “and if there be no

heir after

that it shall be as you wish.” Before the year’s end a son was born to

them in

Narberth. But although six women sat up to watch the mother and the

infant, it

happened towards the morning that they all fell asleep, and Rhiannon

also

slept, and when the women awoke, behold, the boy was gone! “We shall be

burnt

for this,” said the women, and in their terror they concocted a

horrible plot:

they killed a cub of a staghound that had just been littered, and laid

the

bones by Rhiannon, and smeared her face and hands with blood as she

slept, and

when she woke and asked for her child they said she had devoured it in

the

night, and had overcome them with furious strength when they would have

prevented her — and for all she could say or do the six women persisted

in this

story. When

the story was told to Pwyll he would not put away Rhiannon, as his

nobles now

again begged him to do, but a penance was imposed on her — namely, that

she was

to sit every day by the horse-block at the gate of the castle and tell

the tale

to every stranger who came, and offer to carry them on her back into

the

castle. And this she did for part of a year.

The Finding

of Pryderi27

Now at

this time there lived a man named Teirnyon of Gwent Is Coed, who had

the most

beautiful mare in the world, but there was this misfortune attending

her, that

although she foaled on the night of every first of May, none ever knew

what

became of the colts. At last Teirnyon resolved to get at the truth of

the

matter, and the next night on which the mare should foal he armed

himself and

watched in the stable. So the mare foaled, and the colt stood up, and

Teirnyon

was admiring its size and beauty when a great noise was heard outside,

and a

long, clawed arm came through the window of the stable and laid hold of

the

colt. Teirnyon immediately smote at the arm with his sword, and severed

it at

the elbow, so that it fell inside with the colt, and a great wailing

and tumult

was heard outside. He rushed out, leaving the door open behind him, but

could see

nothing because of the darkness of the night, and he followed the noise

a

little way. Then he came back, and behold, at the door he found an

infant in

swaddling-clothes and wrapped in a mantle of satin. He took up the

child and

brought it to where his wife lay sleeping. She had no children, and she

loved

the child when she saw it, and next day pretended to her women that she

had

borne it as her own. And they called its name Gwri of the Golden Hair,

for its

hair was yellow as gold; and it grew so mightily that in two years it

was as

big and strong as a child of six; and ere long the colt that had been

foaled on

the same night was broken in and given him to ride.

While

these things were going on Teirnyon heard the tale of Rhiannon and her

punishment. And as the lad grew up he scanned his face closely and saw

that he

had the features of Pwyll Prince of Dyfed. This he told to his wife,

and they

agreed that the child should be taken to Narberth, and Rhiannon

released from

her penance. As

they drew near to the castle, Teirnyon and two knights and the child

riding on

his colt, there was Rhiannon sitting by the horse-block. “Chieftains,”

said

she, “go not further thus; I will bear every one of you into the

palace, and

this is my penance for slaying my own son and devouring him.” But they

would

not be carried, and went in. Pwyll rejoiced to see Teirnyon, and made a

feast

for him. Afterwards Teirnyon declared to Pwyll and Rhiannon the

adventure of

the man and the colt, and how they had found the boy. “And behold, here

is thy

son, lady,” said Teirnyon, “and whoever told that lie concerning thee

has done

wrong.” All who sat at table recognised the lad at once as the child of

Pwyll,

and Rhiannon cried: “I declare to heaven that if this be true there is

an end

to my trouble.” And a chief named Pendaran said: “Well hast thou named

thy son Pryderi

[trouble], and well becomes him the name of Pryderi son of Pwyll, Lord

of

Annwn.” It was agreed that his name should be Pryderi, and so he was

called

thenceforth. Teirnyon

rode home, overwhelmed with thanks and love and gladness; and Pwyll

offered him

rich gifts of horses and jewels and dogs, but he would take none of

them. And

Pryderi was trained up, as befitted a king’s son, in all noble ways and

accomplishments, and when his father Pwyll died he reigned in his stead

over

the Seven Cantrevs of Dyfed. And he added to them many other fair

dominions,

and at last he took to wife Kicva, daughter of Gwynn Gohoyw, who came

of the

lineage of Prince Casnar of Britain. The Tale of

Bran and Branwen

Bendigeid

Vran, or “Bran the Blessed,” by which latter name we shall designate

him here,

when he had been made King of the Isle of the Mighty (Britain), was one

time in

his court at Harlech. And he had with him his brother Manawyddan son of

Llyr,

and his sister Branwen, and the two sons, Nissyen and Evnissyen, that

Penardun

his mother bore to Eurosswyd. Now Nissyen was a youth of gentle nature,

and would

make peace among his kindred and cause them to be friends when their

wrath was

at its highest; but Evnissyen loved nothing so much as to turn peace

into

contention and strife. One

afternoon, as Bran son of Llyr sat on the rock of Harlech looking out

to sea,

he beheld thirteen ships coming rapidly from Ireland before a fair

wind. They

were gaily furnished, bright flags flying from the masts, and on the

foremost

ship, when they came near, a man could be seen holding up a shield with

the

point upwards in sign of peace.28 When

the strangers landed they saluted Bran and explained their business.

Matholwch,29

King of Ireland, was with them; his were the ships, and he had come to

ask for

the hand in marriage of Bran’s sister, Branwen, so that Ireland and

Britain

might be leagued together and both become more powerful. “Now Branwen

was one

of the three chief ladies of the island, and she was the fairest damsel

in the

world.” The

Irish were hospitably entertained, and after taking counsel with his

lords Bran

agreed to give his sister to Matholwch. The place of the wedding was

fixed at

Aberffraw, and the company assembled for the feast in tents because no

house

could hold the giant form of Bran. They caroused and made merry in

peace and

amity, and Branwen became the bride or the Irish king.

Next

day Evnissyen came by chance to where the horses of Matholwch were

ranged, and

he asked whose they were. “They are the horses of Matholwch, who is

married to

thy sister.” “And is it thus,” said he, “they have done with a maiden

such as

she, and, moreover, my sister, bestowing her without my consent? They

could

offer me no greater insult.” Thereupon he rushed among the horses and

cut off

their lips at the teeth, and their ears to their heads, and their tails

close

to the body, and where he could seize the eyelids he cut them off to

the bone. When

Matholwch heard what had been done he was both angered and bewildered,

and bade

his people put to sea. Bran sent messengers to learn what had happened,

and

when he had been informed he sent Manawyddan and two others to make

atonement.

Matholwch should have sound horses for every one that was injured, and

in

addition a staff of silver as large and as tall as himself, and a plate

of gold

the size of his face. “And let him come and meet me,” he added, “and we

will

make peace in any way he may desire.” But as for Evnissyen, he was the

son of

Bran’s mother, and therefore Bran could not put him to death as he

deserved. The Magic

Cauldron

Matholwch

accepted these terms, but not very cheerfully, and Bran now offered

another

treasure, namely, a magic cauldron which had the property that if a

slain man

were cast into it he would come forth well and sound, only he would not

be able

to speak. Matholwch and Bran then talked about the cauldron, which

originally,

it seems, came from Ireland. There was a lake in that country near to a

mound

(doubtless a fairy mound) which was called the Lake of the Cauldron.

Here

Matholwch had once met a tall and ill-looking fellow with a wife bigger

than himself,

and the cauldron strapped on his back. They took service with

Matholwch. At the

end of a period of six weeks the wife gave birth to a son, who was a

warrior

fully armed. We are apparently to understand that this happened every

six

weeks, for by the end of the year the strange pair, who seem to be a

war-god

and goddess, had several children, whose continual bickering and the

outrages they

committed throughout the land made them hated. At last, to get rid of

them,

Matholwch had a house of iron made, and enticed them into it. He then

barred

the door and heaped coals about the chamber, and blew them into a white

heat,

hoping to roast the whole family to death. As soon, however, as the

iron walls

had grown white-hot and soft the man and his wife burst through them

and got

away, but the children remained behind and were destroyed. Bran then

took up

the story. The man, who was called Llassar Llaesgyvnewid, and his wife

Kymideu

Kymeinvoll, come across to Britain, where Bran took them in, and in

return for

his kindness they gave him the cauldron. And since then they had filled

the

land with their descendants, who prospered everywhere and dwelt in

strong

fortified burgs and had the best weapons that ever were seen. So

Matholwch received the cauldron along with his bride, and sailed back

to

Ireland, where Branwen entertained the lords and ladies of the land,

and gave

to each, as he or she took leave, “either a clasp or a ring or a royal

jewel to

keep, such as it was honourable to be seen departing with.” And when

the year

was out Branwen bore a son to Matholwch, whose name was called Gwern. The

Punishment of Branwen

There

occurs now an unintelligible place in the story. In the second year, it

appears, and not till then, the men of Ireland grew indignant over the

insult

to their king committed by Evnissyen, and took revenge for it by having

Branwen

degraded to the position of a cook, and they caused the butcher every

day to

give her a blow on the ears. They also forbade all ships and

ferry-boats to

cross to Cambria, and any who came thence into Ireland were imprisoned

so that

news of Branwen’s ill-treatment might not come to the ears of Bran. But

Branwen

reared up a young starling in a corner of her kneading-trough, and one

day she

tied a letter under its wing and taught it what to do. It flew away

towards

Britain, and finding Bran at Caer Seiont in Arvon, it lit on his

shoulder,

ruffling its feathers, and the letter was found and read. Bran

immediately

prepared a great hosting for Ireland, and sailed thither with a fleet

of ships,

leaving his land of Britain under his son Caradawc and six other chiefs. The Invasion

of Bran

Soon

there came messengers to Matholwch telling him of a wondrous sight they

had

seen; a wood was growing on the sea, and beside the wood a mountain

with a high

ridge in the middle of it, and two lakes, one at each side. And wood

and

mountain moved towards the shore of Ireland. Branwen is called up to

explain,

if she could, what this meant. She tells them the wood is the masts and

yards

of the fleet of Britain, and the mountain is Bran, her brother, coming

into

shoal water, “for no ship can contain him”; the ridge is his nose, the

lakes

his two eyes.30 The

King of Ireland and his lords at once took counsel together how they

might meet

this danger; and the plan they agreed upon was as follows: A huge hall

should

be built, big enough to hold Bran — this, it was hoped, would placate

him — there

should be a great feast made there for himself and his men, and

Matholwch

should give over the kingdom of Ireland to him and do homage. All this

was done

by Branwen’s advice. But the Irish added a crafty device of their own.

From two

brackets on each of the hundred pillars in the hall should be hung two

leather

bags, with an armed warrior in each of them ready to fall upon the

guests when

the moment should arrive. The Meal-bags

Evnissyen,

however, wandered into the hall before the rest of the host, and

scanning the

arrangements “with fierce and savage looks,” he saw the bags which hung

from

the pillars. “What is in this bag?” said he to one of the Irish. “Meal,

good

soul,” said the Irishman. Evnissyen laid his hand on the bag, and felt

about

with his fingers till he came to the head of the man within it. Then

“he

squeezed the head till he felt his fingers meet together in the brain

through

the bone.” He went to the next bag, and asked the same question.

“Meal,” said

the Irish attendant, but Evnissyen crushed this warrior’s head also,

and thus

he did with all the two hundred bags, even in the case of one warrior

whose

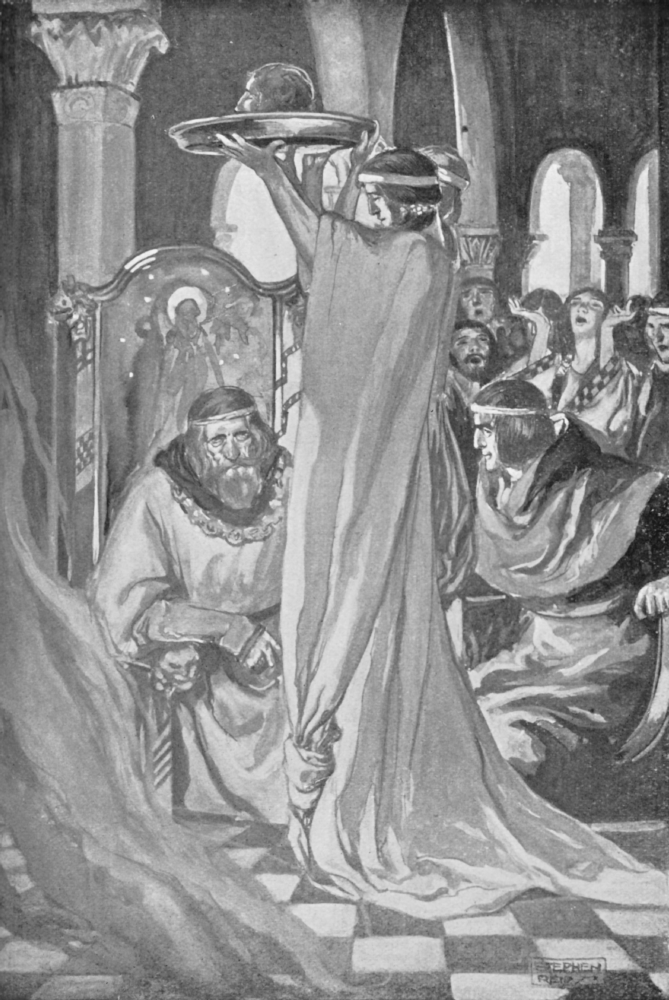

head was covered with an iron helm.  "Evnissyen laid his hand on the bag" Then

the feasting began, and peace and concord reigned, and Matholwch laid

down the

sovranty of Ireland, which was conferred on the boy Gwern. And they all

fondled

and caressed the fair child till he came to Evnissyen, who suddenly

seized him

and flung him into the blazing fire on the hearth. Branwen would have

leaped

after him, but Bran held her back. Then there was arming apace, and

tumult and

shouting, and the Irish and British hosts closed in battle and fought

until the

fall of night. Death of

Evnissyen

But

at night the Irish heated the magic cauldron and threw into it the

bodies of

their dead, who came out next day as good as ever, but dumb. When

Evnissyen saw

this he was smitten with remorse for having brought the men of Britain

into

such a strait: “Evil betide me if I find not a deliverance therefrom.”

So he

hid himself among the Irish dead, and was flung into the cauldron with

the rest

at the end of the second day, when he stretched himself out so that he

rent the

cauldron into four pieces, and his own heart burst with the effort, and

he

died. The

Wonderful Head

In

the end, all the Irishmen were slain, and all but seven of the British

besides

Bran, who was wounded in the foot with a poisoned arrow. Among the

seven were

Pryderi and Manawyddan. Bran then commanded them to cut off his head.

“And take

it with you,” he said, “to London, and there bury it in the White Mount31

looking towards France, and no foreigner shall invade the land while it

is

there. On the way the Head will talk to you, and be as pleasant company

as ever

in life. In Harlech ye will be feasting seven years and the birds of

Rhiannon

will sing to you. And at Gwales in Penvro ye will be feasting fourscore

years,

and the Head will talk to you and be uncorrupted till ye open the door

looking

towards Cornwall. After that ye may no longer tarry, but set forth to

London

and bury the Head.” Then

the seven cut off the head of Bran and went forth, and Branwen with

them, to do

his bidding. But when Branwen came to land at Aber Alaw she cried, “Woe

is me

that I was ever born; two islands have been destroyed because of me.”

And she

uttered a loud groan, and her heart broke. They made her a four-sided

grave on

the banks of the Alaw, and the place was called Ynys Branwen to

this

day.32 The

seven found that in the absence of Bran, Caswallan son of Beli had

conquered

Britain and slain the six captains of Caradawc. By magic art he had

thrown on

Caradawc the Veil of Illusion, and Caradawc saw only the sword which

slew and

slew, but not him who wielded it, and his heart broke for grief at the

sight. They

then went to Harlech and remained there seven years listening to the

singing of

the birds of Rhiannon — “all the songs they had ever heard were

unpleasant

compared thereto.” Then they went to Gwales in Penvro and found a fair

and

spacious hall overlooking the ocean. When they entered it they forgot

all the

sorrow of the past and all that had befallen them, and remained there

fourscore

years in joy and mirth, the wondrous Head talking to them as if it were

alive.

And bards call this “the Entertaining of the Noble Head.” Three doors

were in

the hall, and one of them which looked to Cornwall and to Aber Henvelyn

was

closed, but the other two were open. At the end of the time, Heilyn son

of Gwyn

said, “Evil betide me if I do not open the door to see if what was said

is

true.” And he opened it, and at once remembrance and sorrow fell upon

them, and

they set forth at once for London and buried the Head in the White

Mount, where

it remained until Arthur dug it up, for he would not have the land

defended but

by the strong arm. And this was “the Third Fatal Disclosure” in Britain. So

ends this wild tale, which is evidently full of mythological elements,

the key

to which has long been lost. The touches of Northern ferocity which

occur in it

have made some critics suspect the influence of Norse or Icelandic

literature

in giving it its present form. The character of Evnissyen would

certainly lend

countenance to this conjecture. The typical mischief-maker of course

occurs in

purely Celtic sagas, but not commonly in combination with the heroic

strain

shown in Evnissyen’s end, nor does the Irish “poison-tongue” ascend to

anything

like the same height of daimonic malignity.

The Tale of

Pryderi and Manawyddan

After

the events of the previous tales Pryderi and Manawyddan retired to the

dominions of the former, and Manawyddan took to wife Rhiannon, the

mother of

his friend. There they lived happily and prosperously till one day,

while they

were at the Gorsedd, or Mound, near Narberth, a peal of thunder was

heard and a

thick mist fell so that nothing could be seen all round. When the mist

cleared

away, behold, the land was bare before them — neither houses nor people

nor

cattle nor crops were to be seen, but all was desert and uninhabited.

The

palace of Narberth was still standing, but it was empty and desolate —

none

remained except Pryderi and Manawyddan and their wives, Kicva and

Rhiannon. Two

years they lived on the provisions they had, and on the prey they

killed, and

on wild honey; and then they began to be weary. “Let us go into

Lloegyr,”33

then said Manawyddan, “and seek out some craft to support ourselves.”

So they

went to Hereford and settled there, and Manawyddan and Pryderi began to

make

saddles and housings, and Manawyddan decorated them with blue enamel as

he had

learned from a great craftsman, Llasar Llaesgywydd. After a time,

however, the

other saddlers of Hereford, finding that no man would purchase any but

the work

of Manawyddan, conspired to kill them. And Pryderi would have fought

with them,

but Manawyddan held it better to withdraw elsewhere, and so they did. They

settled then in another city, where they made shields such as never

were seen,

and here, too, in the end, the rival craftsmen drove them out. And this

happened also in another town where they made shoes; and at last they

resolved

to go back to Dyfed. Then they gathered their dogs about them and lived

by

hunting as before. One

day they started a wild white boar, and chased him in vain until he led

them up

to a vast and lofty castle, all newly built in a place where they had

never

seen a building before. The boar ran into the castle, the dogs followed

him,

and Pryderi, against the counsel of Manawyddan, who knew there was

magic afoot,

went in to seek for the dogs. He

found in the centre of the court a marble fountain beside which stood a

golden

bowl on a marble slab, and being struck by the rich workmanship of the

bowl, he

laid hold of it to examine it, when he could neither withdraw his hand

nor

utter a single sound, but he remained there, transfixed and dumb,

beside the

fountain. Manawyddan

went back to Narberth and told the story to Rhiannon. “An evil

companion hast

thou been,” said she, “and a good companion hast thou lost.” Next

day she went herself to explore the castle. She found Pryderi still

clinging to

the bowl and unable to speak. She also, then, laid hold of the bowl,

when the

same fate befell her, and immediately afterwards came a peal of

thunder, and a

heavy mist fell, and when it cleared off the castle had vanished with

all that

it contained, including the two spell-bound wanderers.

Manawyddan

then went back to Narberth, where only Kicva, Pryderi’s wife, now

remained. And

when she saw none but herself and Manawyddan in the place, “she

sorrowed so

that she cared not whether she lived or died.” When Manawyddan saw this

he said

to her, “Thou art in the wrong if through fear of me thou grievest

thus. I

declare to thee were I in the dawn of youth I would keep my faith unto

Pryderi,

and unto thee also will I keep it.” “Heaven reward thee,” she said,

“and that

is what I deemed of thee.” And thereupon she took courage and was glad. Kicva

and Manawyddan then again tried to support themselves by shoemaking in

Lloegyr,

but the same hostility drove them back to Dyfed. This time, however,

Manawyddan

took back with him a load of wheat, and he sowed it, and he prepared

three

crofts for a wheat crop. Thus the time passed till the fields were

ripe. And he

looked at one of the crofts and said, “I will reap this to-morrow.” But

on the

morrow when he went out in the grey dawn he found nothing there but

bare straw

— every ear had been cut off from the stalk and carried away. Next

day it was the same with the second croft. But on the following night

he armed

himself and sat up to watch the third croft to see who was plundering

him. At

midnight, as he watched, he heard a loud noise, and behold, a mighty

host of

mice came pouring into the croft, and they climbed up each on a stalk

and

nibbled off the ears and made away with them. He chased them in anger,

but they

fled far faster than he could run, all save one which was slower in its

movements, and this he barely managed to overtake, and he bound it into

his

glove and took it home to Narberth, and told Kicva what had happened.

“To-morrow,” he said, “I will hang the robber I have caught,” but Kicva

thought

it beneath his dignity to take vengeance on a mouse.

Next

day he went up to the Mound of Narberth and set up two forks for a

gallows on

the highest part of the hill. As he was doing this a poor scholar came

towards

him, and he was the first person Manawyddan had seen in Dyfed, except

his own

companions, since the enchantment began.

The

scholar asked him what he was about and begged him to let go the mouse

— “Ill

doth it become a man of thy rank to touch such a reptile as this.” “I

will not

let it go, by Heaven,” said Manawyddan, and by that he abode, although

the

scholar offered him a pound of money to let it go free. “I care not,”

said the

scholar, “except that I would not see a man of rank touching such a

reptile,”

and with that he went his way. As

Manawyddan

was placing the cross-beam on the two forks of his gallows, a priest

came

towards him riding on a horse with trappings, and the same conversation

ensued.

The priest offered three pounds for the mouse’s life, but Manawyddan

refused to

take any price for it. “Willingly, lord, do thy good pleasure,” said

the

priest, and he, too, went his way. Then

Manawyddan put a noose about the mouse’s neck and was about to draw it

up when

he saw coming towards him a bishop with a great retinue of

sumpter-horses and