| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Myths & Legends: The Celtic Race Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

V: TALES OF THE ULTONIAN CYCLE The Curse of Macha

The

centre of interest in Irish legend now shifts from Tara to Ulster, and a

multitude of heroic tales gather round the Ulster king Conor mac Nessa, round

Cuchulain,1 his great vassal, and the Red Branch Order of chivalry,

which had its seat in Emain Macha. The

legend of the foundation of Emain Macha has already been told.2 But

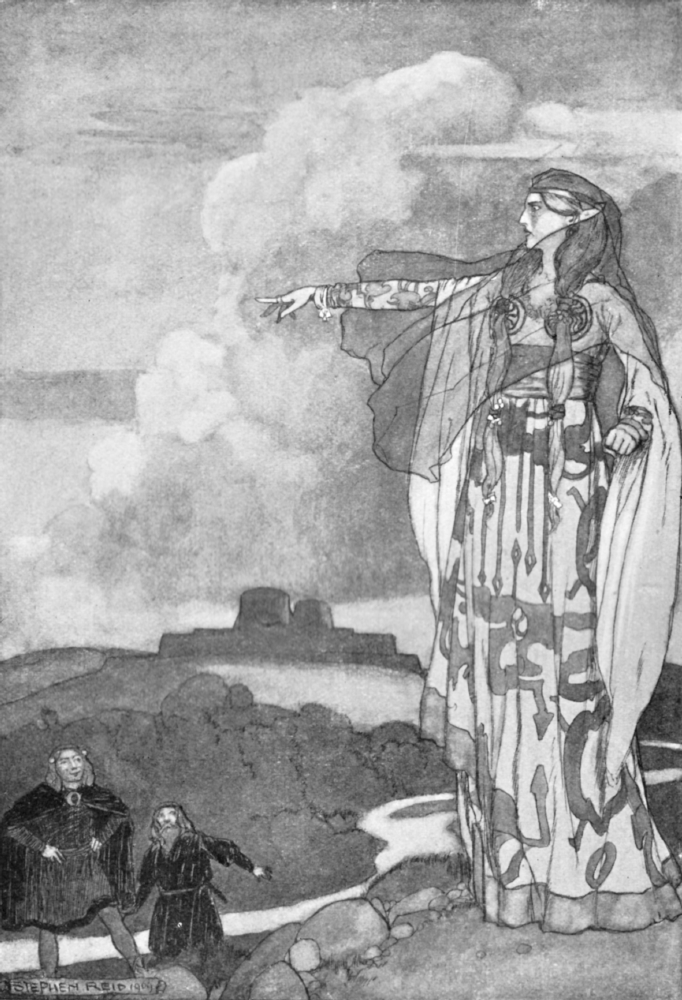

Macha, who was no mere woman, but a supernatural being, appears again in connexion

with the history of Ulster in a very curious tale which was supposed to account

for the strange debility or helplessness that at critical moments sometimes

fell, it was believed, upon the warriors of the province. The

legend tells that a wealthy Ulster farmer named Crundchu, son of Agnoman,

dwelling in a solitary place among the hills, found one day in his dūn a young

woman of great beauty and in splendid array, whom he had never seen before.

Crundchu, we are told, was a widower, his wife having died after bearing him

four sons. The strange woman, without a word, set herself to do the houshold

tasks, prepared dinner, milked the cow, and took on herself all the duties of

the mistress of the household. At night she lay down at Crundchu’s side, and thereafter

dwelt with him as his wife; and they loved each other dearly. Her name was

Macha. One

day Crundchu prepared himself to go to a great fair or assembly of the Ultonians,

where there would be feasting and horse-racing, tournaments and music, and

merrymaking of all kinds. Macha begged her husband not to go. He persisted.

“Then,” she said, “at least do not speak

of me in the assembly, for I may dwell with you only so long as I am not spoken

of.”  It

has been observed that we have here the earliest appearance in post-classical

European literature of the well-known motive of the fairy bride who can stay

with her mortal lover only so long as certain conditions are observed, such as

that he shall not spy upon her, ill-treat her, or ask of her origin. Crundchu

promised to obey the injunction, and went to the festival. Here the two horses

of the king carried off prize after prize in the racing, and the people cried:

“There is not in Ireland a swifter than the King’s pair of horses.” “I

have a wife at home,” said Crundchu, in a moment of forgetfulness, “who can run

quicker than these horses.” “Seize

that man,” said the angry king, “and hold him till his wife be brought to the

contest.” So

messengers went for Macha, and she was brought before the assembly; and she was

with child. The king bade her prepare for the race. She pleaded her condition.

“I am close upon my hour,” she said. “Then hew her man in pieces,” said the

king to his guards. Macha turned to the bystanders. “Help me,” she cried, “for

a mother hath borne each of you! Give me but a short delay till I am

delivered.” But the king and all the crowd in their savage lust for sport would

hear of no delay. “Then bring up the horses,” said Macha, “and because you have

no pity a heavier infamy shall fall upon you.” So she raced against the horses,

and outran them, but as she came to the goal she gave a great cry, and her

travail seized her, and she gave birth to twin children. As she uttered that

cry, however, all the spectators felt themselves seized with pangs like her own

and had no more strength than a woman in her travail. And Macha prophesied:

“From this hour the shame you have wrought on me will fall upon each man of

Ulster. In the hours of your greatest need ye shall be weak and helpless as

women in childbirth, and this shall endure for five days and four nights — to

the ninth generation the curse shall be upon you.” And so it came to pass; and this

is the cause of the Debility of the Ultonians that was wont to afflict the

warriors of the province. Conor mac Nessa

The

chief occasion on which this Debility was manifested was when Maev, Queen of

Connacht, made the famous Cattle-raid of Quelgny (Tain Bo Cuailgné),

which forms the subject of the greatest tale in Irish literature. We have now

to relate the preliminary history leading up to this epic tale and introducing

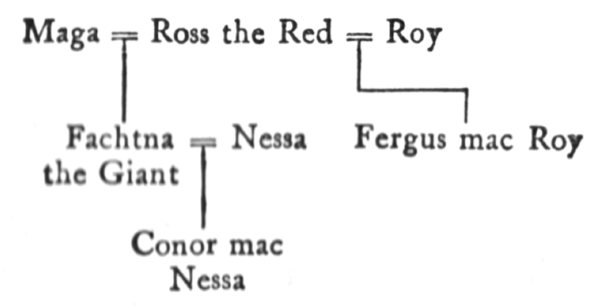

its chief characters. Fachtna

the Giant, King of Ulster, had to wife Nessa, daughter of Echid Yellow-heel,

and she bore him a son named Conor. But when Fachtna died Fergus son of Roy,

his half-brother, succeeded him, Conor being then but a youth. Now Fergus loved

Nessa, and would have wedded her, but she made conditions. “Let my son Conor

reign one year,” she said, “so that his posterity may be the descendants of a

king, and I consent.” Fergus agreed, and young Conor took the throne. But so

wise and prosperous was his rule and so sagacious his judgments that, at the

year’s end, the people, as Nessa foresaw, would have him remain king; and

Fergus, who loved the feast and the chase better than the toils of kingship,

was content to have it so, and remained at Conor’s court for a time, great,

honoured, and happy, but king no longer.

The Red Branch

In

his time was the glory of the “Red Branch” in Ulster, who were the offspring of

Ross the Red, King of Ulster, with collateral relatives and allies, forming

ultimately a kind of warlike Order. Most of the Red Branch heroes appear in the

Ultonian Cycle of legend, so that a statement of their names and relationships

may be usefully placed here before we proceed to speak of their doings. It is

noticeable that they have a partly supernatural ancestry. Ross the Red, it is

said, wedded a Danaan woman, Maga, daughter of Angus Ōg.3 As a

second wife he wedded a maiden named Roy. His descendants are as follows:  But

Maga was also wedded to the Druid Cathbad, and by him had three daughters,

whose descendants played a notable part in the Ultonian legendary cycle.

Birth of Cuchulain It

was during the reign of Conor mac Nessa that the birth of the mightiest hero of

the Celtic race, Cuchulain, came about, and this was the manner of it. The

maiden Dectera, daughter of Cathbad, with fifty young girls, her companions at

the court of Conor, one day disappeared, and for three years no searching

availed to discover their dwelling-place or their fate. At last one summer day

a flock of birds descended on the fields about Emain Macha and began to destroy

the crops and fruit. The king, with Fergus and others of his nobles, went out

against them with slings, but the birds flew only a little way off, luring the

party on and on till at last they found themselves near the Fairy Mound of

Angus on the river Boyne. Night fell, and the king sent Fergus with a party to

discover some habitation where they might sleep. A hut was found, where they

betook themselves to rest, but one of them, exploring further, came to a noble

mansion by the river, and on entering it was met by a young man of splendid

appearance. With the stranger was a lovely woman, his wife, and fifty maidens,

who saluted the Ulster warrior with joy. And he recognised in them Dectera and her

maidens, whom they had missed for three years, and in the glorious youth Lugh

of the Long Arm, son of Ethlinn. He went back with his tale to the king, who

immediately sent for Dectera to come to him. She, alleging that she was ill,

requested a delay; and so the night passed; but in the morning there was found

in the hut among the Ulster warriors a new-born male infant. It was Dectera’s

gift to Ulster, and for this purpose she had lured them to the fairy palace by

the Boyne. The child was taken home by the warriors and was given to Dectera’s

sister, Finchoom, who was then nursing her own child, Conall, and the boy’s

name was called Setanta. And the part of

Ulster from Dundalk southward to Usna in Meath,

which is called the Plain of Murthemney, was allotted for his inheritance, and

in later days his fortress and dwelling-place was in Dundalk.  It is

said that the Druid Morann prophesied over the infant: “His praise will be in

the mouths of all men; charioteers and warriors, kings and sages will recount

his deeds; he will win the love of many. This child will avenge all your

wrongs; he will give combat at your fords, he will decide all your quarrels.” The Hound of Cullan

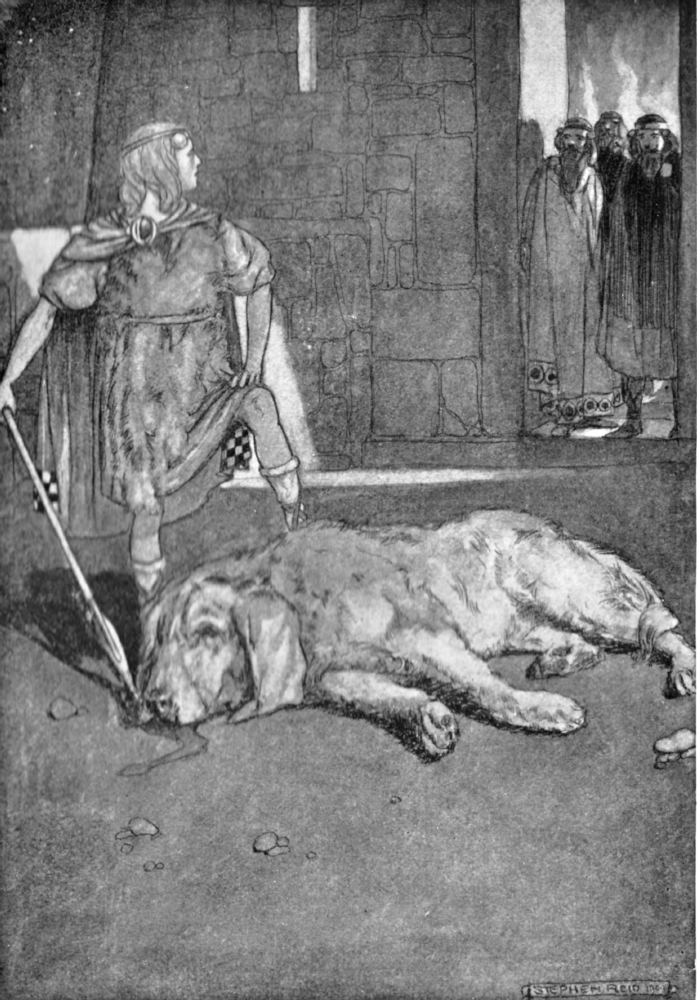

When

he was old enough the boy Setanta went to the court of Conor to be brought up

and instructed along with the other sons of princes and chieftains. It was now

that the event occurred from which he got the name of Cuchulain, by which he

was hereafter to be known. One

afternoon King Conor and his nobles were going to a feast to which they were

bidden at the dūn of a wealthy smith named Cullan, in Quelgny, where they also

meant to spend the night. Setanta was to accompany them, but as the cavalcade

set off he was in the midst of a game of hurley with his companions and bade

the king go forward, saying he would follow later when his play was done. The

royal company arrived at their destination as night began to fall. Cullan

received them hospitably, and in the great hall they made merry over meat and

wine while the lord of the house barred the gates of his fortress and let loose

outside a huge and ferocious dog which every night guarded the lonely mansion,

and under whose protection, it was said, Cullan feared nothing less than the

onset of an army. But

they had forgotten Setanta! In the middle of the laughter and music of the

feast a terrible sound was heard which brought every man to his feet in an

instant. It was the tremendous baying of the hound of Cullan, giving tongue as

it saw a stranger approach. Soon the noise changed to the howls of a fierce

combat, but, on rushing to the gates, they saw in the glare of the lanterns a

young boy and the hound lying dead at his feet. When it flew at him he had

seized it by the throat and dashed its life out against the side-posts of the

gate. The warriors bore in the lad with rejoicing and wonder, but soon the

triumph ceased, for there stood their host, silent and sorrowful over the body

of his faithful friend, who had died for the safety of his house and would

never guard it more.  “Give

me,” then said the lad Setanta, “a whelp of that hound, O Cullan, and I will

train him to be all to you that his sire was. And until then give me shield and

spear and I will myself guard your house; never hound guarded it better than I

will.” And

all the company shouted applause at the generous pledge, and on the spot, as a

commemoration of his first deed of valour, they named the lad Cuchulain,5

the Hound of Cullan, and by that name he was known until he died. Cuchulain Assumes Arms

When

he was older, and near the time when he might assume the weapons of manhood, it

chanced one day that he passed close by where Cathbad the Druid was teaching to

certain of his pupils the art of divination and augury. One of them asked of

Cathbad for what kind of enterprise that same day might be favourable; and

Cathbad, having worked a spell of divination, said: “The youth who should take

up arms on this day would become of all men in Erin most famous for great

deeds, yet will his life be short and fleeting.” Cuchulain passed on as though

he marked it not, and he came before the king. “What wilt thou?” asked Conor.

“To take the arms of manhood,” said Cuchulain. “So be it,” said the king, and

he gave the lad two great spears. But Cuchulain shook them in his hand, and the

staves splintered and broke. And so he did with many others; and the chariots

in which they set him to drive he broke to pieces with stamping of his foot, until

at last the king’s own chariot of war and his two spears and sword were brought

to the lad, and these he could not break, do what he would; so this equipment

he retained. His Courtship of Emer

The

young Cuchulain was by this grown so fair and noble a youth that every maid or

matron on whom he looked was bewitched by him, and the men of Ulster bade him take

a wife of his own. But none were pleasing to him, till at last he saw the

lovely maiden Emer, daughter of Forgall, the lord of Lusca,6 and he

resolved to woo her for his bride. So he bade harness his chariot, and with

Laeg, his friend and charioteer, he journeyed to Dūn Forgall. As he

drew near, the maiden was with her companions, daughters of the vassals of

Forgall, and she was teaching them embroidery, for in that art she excelled all

women. She had “the six gifts of womanhood — the gift of beauty, the gift of

voice, the gift of sweet speech, the gift of needlework, the gift of wisdom,

and the gift of chastity.” Hearing

the thunder of horse-hoofs and the clangour of the chariot from afar, she bade

one of the maidens go to the rampart of the Dūn and tell her what she saw. “A

chariot is coming on,” said the maiden, “drawn by two steeds with tossing

heads, fierce and powerful; one is grey, the other black. They breathe fire

from their jaws, and the clods of turf they throw up behind them as they race

are like a flock of birds that follow in their track. In the chariot is a dark,

sad man, comeliest of the men of Erin. He is clad in a crimson cloak, with a

brooch of gold, and on his back is a crimson shield with a silver rim wrought

with figures of beasts. With him as his charioteer is a tall, slender, freckled

man with curling red hair held by a fillet of bronze, with plates of gold at

either side of his face. With a goad of red gold he urges the horses.” When

the chariot drew up Emer went to meet Cuchulain and saluted him. But when he

urged his love upon her she told him of the might and the wiliness of her

father Forgall, and of the strength of the champions that guarded her lest she

should wed against his will. And when he pressed her more she said: “I may not

marry before my sister Fial, who is older than I. She is with me here — she is

excellent in handiwork.” “It is not Fial whom I love,” said Cuchulain. Then as

they were conversing he saw the breast of the maiden over the bosom of her smock,

and said to her: “Fair is this plain, the plain of the noble yoke.” “None comes

to this plain,” said she, “who has not slain his hundreds, and thy deeds are

still to do.” So

Cuchulain then left her, and drove back to Emain Macha. Cuchulain in the Land of Skatha

Next

day Cuchulain bethought himself how he could prepare himself for war and for

the deeds of heroism which Emer had demanded of him. Now he had heard of a

mighty woman-warrior named Skatha, who dwelt in the Land of Shadows,7

and who could teach to young heroes who came to her wonderful feats of arms. So

Cuchulain went overseas to find her, and many dangers he had to meet, black

forests and desert plains to traverse, before he could get tidings of Skatha

and her land. At last he came to the Plain of Ill-luck, where he could not

cross without being mired in its bottomless bogs or sticky clay, and while he

was debating what he should do he saw coming towards him a young man with a

face that shone like the sun,8 and whose very look put cheerfulness

and hope into his heart. The young man gave him a wheel and told him to roll it

before him on the plain, and to follow it whithersoever it went. So Cuchulain

set the wheel rolling, and as it went it blazed with light that shot like rays

from its rim, and the heat of it made a firm path across the quagmire, where Cuchulain

followed safely. When

he had passed the Plain of Ill-luck, and escaped the beasts of the Perilous

Glen, he came to the Bridge of the Leaps, beyond which was the country of

Skatha. Here he found on the hither side many sons of the princes of Ireland

who were come to learn feats of war from Skatha, and they were playing at

hurley on the green. And among them was his friend Ferdia, son of the Firbolg,

Daman; and they all asked him of the news from Ireland. When he had told them

all he asked Ferdia how he should pass to the dūn of Skatha. Now the Bridge of

Leaps was very narrow and very high, and it crossed a gorge where far below

swung the tides of a boiling sea, in which ravenous monsters could be seen

swimming. “Not

one of us has crossed that bridge,” said Ferdia, “for there are two feats that

Skatha teaches last, and one is the leap across the bridge, and the other the

thrust of the Gae Bolg.9 For if a man step upon one end of that

bridge, the middle straightway rises up and flings him back, and if he leap

upon it he may chance to miss his footing and fall into the gulf, where the

sea-monsters are waiting for him.” But

Cuchulain waited till evening, when he had recovered his strength from his long

journey, and then essayed the crossing of the bridge. Three times he ran

towards it from a distance, gathering all his powers together, and strove to

leap upon the middle, but three times it rose against him and flung him back,

while his companions jeered at him because he would not wait for the help of

Skatha. But at the fourth leap he lit fairly on the centre of the bridge, and

with one leap more he was across it, and stood before the strong fortress of

Skatha; and she wondered at his courage and vigour, and admitted him to be her

pupil. For a

year and a day Cuchulain abode with Skatha, and all the feats she had to teach

he learned easily, and last of all she taught him the use of the Gae Bolg, and

gave him that dreadful weapon, which she had deemed no champion before him good

enough to have. And the manner of using the Gae Bolg was that it was thrown

with the foot, and if it entered an enemy’s body it filled every limb and

crevice of him with its barbs. While Cuchulain dwelt with Skatha his friend

above all friends and his rival in skill and valour was Ferdia, and ere they

parted they vowed to love and help one another as long as they should live. Cuchulain and Aifa

Now

whilst Cuchulain was in the Land of the Shadows it chanced that Skatha made war

on the people of the Princess Aifa, who was the fiercest and strongest of the

woman-warriors of the world, so that even Skatha feared to meet her in arms. On

going forth to the war, therefore, Skatha mixed with Cuchulain’s drink a sleepy

herb so that he should not wake for four-and-twenty hours, by which time the

host would be far on its way, for she feared lest evil should come to him ere

he had got his full strength. But the potion that would have served another man

for a day and a night only held Cuchulain for one hour; and when he waked up he

seized his arms and followed the host by its chariot-tracks till he came up

with them. Then it is said that Skatha uttered a sigh, for she knew that he

would not be restrained from the war. When

the armies met, Cuchulain and the two sons of Skatha wrought great deeds on the

foe, and slew six of the mightiest of Aifa’s warriors. Then Aifa sent word to

Skatha and challenged her to single combat. But Cuchulain declared that he would

meet the fair Fury in place of Skatha, and he asked first of all what were the

things she most valued. “What Aifa loves most,” said Skatha, “are her two

horses, her chariot and her charioteer.” Then the pair met in single combat,

and every champion’s feat which they knew they tried on each other in vain,

till at last a blow of Aifa’s shattered the sword of Cuchulain to the hilt. At

this Cuchulain cried out: “Ah me! behold the chariot and horses of Aifa, fallen

into the glen!” Aifa glanced round, and Cuchulain, rushing in, seized her round

the waist and slung her over his shoulder and bore her back to the camp of Skatha.

There he flung her on the ground and put his knife to her throat. She begged

for her life, and Cuchulain granted it on condition that she made a lasting

peace with Skatha, and gave hostages for her fulfilment of the pledge. To this

she agreed, and Cuchulain and she became not only friends but lovers. The Tragedy of Cuchulain and Connla

Before

Cuchulain left the Land of Shadows he gave Aifa a golden ring, saying that if

she should bear him a son he was to be sent to seek his father in Erin so soon

as he should have grown so that his finger would fit the ring. And Cuchulain

said, “Charge him under geise that he shall not make himself known, that

he never turn out of the way for any man, nor ever refuse a combat. And be his

name called Connla.” In

later years it is narrated that one day when King Conor of Ulster and the lords

of Ulster were at a festal gathering on the Strand of the Footprints they saw

coming towards them across the sea a little boat of bronze, and in it a young

lad with gilded oars in his hands. In the boat was a heap of stones, and ever

and anon the lad would put one of these stones into a sling and cast it at a

flying sea-bird in such fashion that it would bring down the bird alive to his

feet. And many other wonderful feats of skill he did. Then Conor said, as the

boat drew nearer: “If the grown men of that lad’s country came here they would

surely grind us to powder. Woe to the land into which that boy shall come!” When

the boy came to land, a messenger, Condery, was sent to bid him be off. “I will

not turn back for thee,” said the lad, and Condery repeated what he had said to

the king. Then Conall of the Victories was sent against him, but the lad slung

a great stone at him, and the whizz and wind of it knocked him down, and the

lad sprang upon him, and bound his arms with the strap of his shield. And so

man after man was served; some were bound, and some were slain, but the lad

defied the whole power of Ulster to turn him back, nor would he tell his name

or lineage. “Send

for Cuchulain,” then said King Conor. And they sent a messenger to Dundalk,

where Cuchulain was with Emer his wife, and bade him come to do battle against

a stranger boy whom Conall of the Victories could not overcome. Emer threw her

arm round Cuchulain’s neck. “Do not go,” she entreated. “Surely this is the son

of Aifa. Slay not thine only son.” But Cuchulain said: “Forbear, woman! Were it

Connla himself I would slay him for the honour of Ulster,” and he bade yoke his

chariot and went to the Strand. Here he found the boy tossing up his weapons

and doing marvellous feats with them. “Delightful is thy play, boy,” said

Cuchulain; “who art thou and whence dost thou come?” “I may not reveal that,”

said the lad. “Then thou shalt die,” said Cuchulain. “So be it,” said the lad,

and then they fought with swords for a while, till the lad delicately shore off

a lock of Cuchulain’s hair. “Enough of trifling,” said Cuchulain, and they closed

with each other, but the lad planted himself on a rock and stood so firm that

Cuchulain could not move him, and in the stubborn wrestling they had the lad’s

two feet sank deep into the stone and made the footprints whence the Strand of

the Footprints has its name. At last they both fell into the sea, and Cuchulain

was near being drowned, till he bethought himself of the Gae Bolg, and he drove

that weapon against the lad and it ripped up his belly. “That is what Skatha

never taught me,” cried the lad. “Woe is me, for I am hurt.” Cuchulain looked

at him and saw the ring on his finger. “It is true,” he said; and he took up

the boy and bore him on shore and laid him down before Conor and the lords of

Ulster. “Here is my son for you, men of Ulster,” he said. And the boy said: “It

is true. And if I had five years to grow among you, you would conquer the world

on every side of you and rule as far as Rome. But since it is as it is, point out

to me the famous warriors that are here, that I may know them and take leave of

them before I die.” Then one after another they were brought to him, and he

kissed them and took leave of his father, and he died; and the men of Ulster

made his grave and set up his pillar-stone with great mourning. This was the

only son Cuchulain ever had, and this son he slew. This

tale, as I have given it here, dates from the ninth century, and is found in

the “Yellow Book of Lecan.” There are many other Gaelic versions of it in

poetry and prose. It is one of the earliest extant appearances in literature of

the since well-known theme of the slaying of a heroic son by his father. The

Persian rendering of it in the tale of Sohrab and Rustum has been made familiar

by Matthew Arnold’s fine poem. In the Irish version it will be noted that the

father is not without a suspicion of the identity of his antagonist, but he

does battle with him under the stimulus of that passionate sense of loyalty to

his prince and province which was Cuchulain’s most signal characteristic. To

complete the story of Aifa and her son we have anticipated events, and now turn

back to take up the thread again. Cuchulain’s First Foray

After

a year and a day of training in warfare under Skatha, Cuchulain returned to

Erin, eager to test his prowess and to win Emer for his wife. So he bade

harness his chariot and drove out to make a foray upon the fords and marches of

Connacht, for between Connacht and Ulster there was always an angry surf of

fighting along the borders. And

first he drove to the White Cairn, which is on the highest of the Mountains of

Mourne, and surveyed the land of Ulster spread out smiling in the sunshine far

below and bade his charioteer tell him the name of every hill and plain and dūn

that he saw. Then turning southwards he looked over the plains of Bregia, and

the charioteer pointed out to him Tara and Teltin, and Brugh na Boyna and the

great dūn of the sons of Nechtan. “Are they,” asked Cuchulain, “those sons of

Nechtan of whom it is said that more of the men of Ulster have fallen by their

hands than are yet living on the earth?” “The same,” said the charioteer. “Then

let us drive thither,” said Cuchulain. So, much unwilling, the charioteer drove

to the fortress of the sons of Nechtan, and there on the green before it they found

a pillar-stone, and round it a collar of bronze having on it writing in Ogham.

This Cuchulain read, and it declared that any man of age to bear arms who

should come to that green should hold it geis

for him to depart without having challenged one of the dwellers in the dūn to

single combat. Then Cuchulain flung his arms round the stone, and, swaying it

backwards and forwards, heaved it at last out of the earth and flung it, collar

and all, into the river that ran hard by. “Surely,” said the charioteer, “thou art

seeking for a violent death, and now thou wilt find it without delay.” Then

Foill son of Nechtan came forth from the dūn, and seeing Cuchulain, whom he

deemed but a lad, he was annoyed. But Cuchulain bade him fetch his arms, “for I

slay not drivers nor messengers nor unarmed men,” and Foill went back into the

dūn. “Thou canst not slay him,” then said the charioteer, “for he is

invulnerable by magic power to the point or edge of any blade.” But Cuchulain

put in his sling a ball of tempered iron, and when Foill appeared he slung at

him so that it struck his forehead, and went clean through brain and skull; and

Cuchulain took his head and bound it to his chariot-rim. And other sons of

Nechtan, issuing forth, he fought with and slew by sword or spear; and then he

fired the dūn and left it in a blaze and drove on exultant. And on the way he

saw a flock of wild swans, and sixteen of them he brought down alive with his

sling, and tied them to the chariot; and seeing a herd of wild deer which his

horses could not overtake he lighted down and chased them on foot till he

caught two great stags, and with thongs and ropes he made them fast to the

chariot. But

at Emain Macha a scout of King Conor came running in to give him news. “Behold,

a solitary chariot is approaching swiftly over the plain; wild white birds

flutter round it and wild stags are tethered to it; it is decked all round with

the bleeding heads of enemies.” And Conor looked to see who was approaching,

and he saw that Cuchulain was in his battle-fury, and would deal death around

him whomsoever he met; so he hastily gave order that a troop of the women of

Emania should go forth to meet him, and, having stripped off their clothing,

should stand naked in the way. This they did, and when the lad saw them,

smitten with shame, he bowed his head upon the chariot-rim. Then Conor’s men

instantly seized him and plunged him into a vat of cold water which had been

made ready, but the water boiled around him and the staves and hoops of the vat

were burst asunder. This they did again and yet again, and at last his fury

left him, and his natural form and aspect were restored. Then they clad him in

fresh raiment and bade him in to the feast in the king’s banqueting-hall. The Winning of Emer

Next day

he went to the dūn of Forgall the Wily, father of Emer, and he leaped “the

hero’s salmon leap,” that he had learned of Skatha, over the high ramparts of

the dūn. Then the mighty men of Forgall set on him, and he dealt but three

blows, and each blow slew eight men, and Forgall himself fell lifeless in

leaping from the rampart of the dūn to escape Cuchulain. So he carried off Emer

and her foster-sister and two loads of gold and silver. But outside the dūn the

sister of Forgall raised a host against him, and his battle-fury came on him,

and furious were the blows he dealt, so that the ford of Glondath ran blood and

the turf on Crofot was trampled into bloody mire. A hundred he slew at every

ford from Olbiny to the Boyne; and so was Emer won as she desired, and he

brought her to Emain Macha and made her his wife, and they were not parted

again until he died. Cuchulain Champion of Erin

A

lord of Ulster named Briccriu of the Poisoned Tongue once made a feast to which

he bade King Conor and all the heroes of the Red Branch, and because it was

always his delight to stir up strife among men or women he set the heroes

contending among themselves as to who was the champion of the land of Erin. At

last it was agreed that the championship must lie among three of them, namely,

Cuchulain, and Conall of the Victories and Laery the Triumphant. To decide

between these three a demon named The Terrible was summoned from a lake in the

depth of which he dwelt. He proposed to the heroes a test of courage. Any one

of them, he said, might cut off his head to-day provided that he, the claimant

of the championship, would lay down his own head for the axe to-morrow. Conall and

Laery shrank from the test, but Cuchulain accepted it, and after reciting a

charm over his sword, he cut off the head of the demon, who immediately rose,

and taking the bleeding head in one hand and his axe in the other, plunged into

the lake. Next

day he reappeared, whole and sound, to claim the fulfilment of the bargain.

Cuchulain, quailing but resolute, laid his head on the block. “Stretch out your

neck, wretch,” cried the demon; “’tis too short for me to strike at.” Cuchulain

does as he is bidden. The demon swings his axe thrice over his victim, brings

down the butt with a crash on the block, and then bids Cuchulain rise unhurt,

Champion of Ireland and her boldest man.

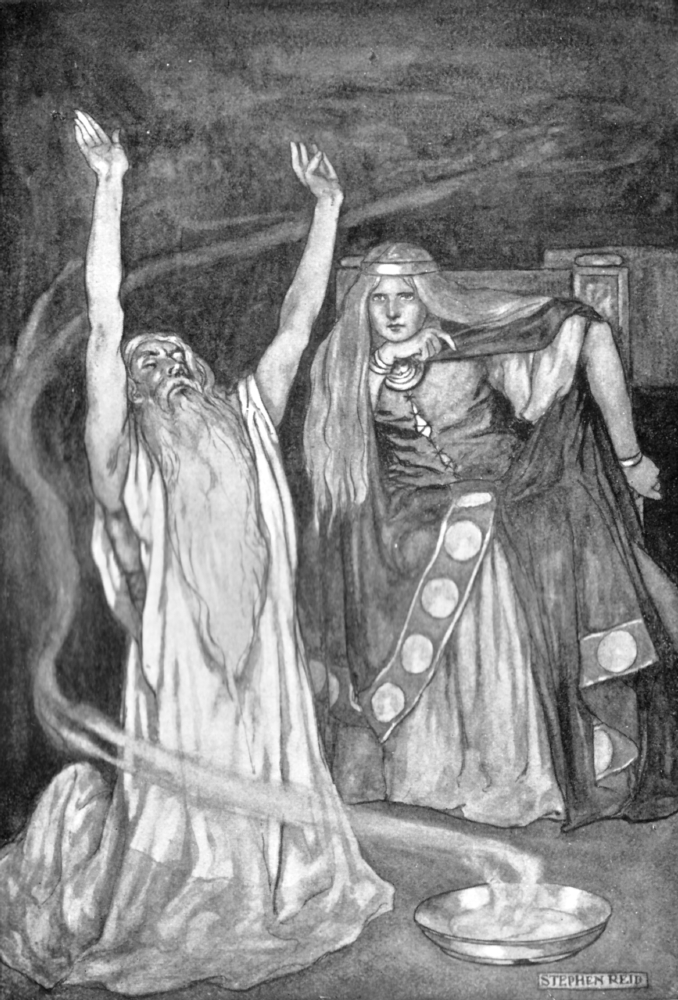

Deirdre and the Sons of Usna

We

have now to turn to a story in which Cuchulain takes no part. It is the chief

of the preliminary tales to the Cattle-spoil of Quelgny. There

was among the lords of Ulster, it is said, one named Felim son of Dall, who on

a certain day made a great feast for the king. And the king came with his Druid

Cathbad, and Fergus mac Roy, and many heroes of the Red Branch, and while they

were making merry over the roasted flesh and wheaten cakes and Greek wine a

messenger from the women’s apartments came to tell Felim that his wife had just

borne him a daughter. So all the lords and warriors drank health to the

new-born infant, and the king bade Cathbade perform divination in the manner of

the Druids and foretell what the future would have in store for Felim’s babe.

Cathbad gazed upon the stars and drew the horoscope of the child, and he was

much troubled; and at length he said: “The infant shall be fairest among the

women of Erin, and shall wed a king, but because of her shall death and ruin

come upon the Province of Ulster.” Then the warriors would have put her to

death upon the spot, but Conor forbade them. “I will avert the doom,” he said, “for

she shall wed no foreign king, but she shall be my own mate when she is of

age.” So he took away the child, and committed it to his nurse Levarcam, and

the name they gave it was Deirdre. And Conor charged Levarcam that the child

should be brought up in a strong dūn in the solitude of a great wood, and that

no young man should see her or she him until she was of marriageable age for

the king to wed. And there she dwelt, seeing none but her nurse and Cathbad,

and sometimes the king, now growing an aged man, who would visit the dūn from

time to time to see that all was well with the folk there, and that his

commands were observed. One

day, when the time for the marriage of Deirdre and Conor was drawing near,

Deirdre and Levarcam looked over the rampart of their dūn. It was winter, a

heavy snow had fallen in the night, and in the still, frosty air the trees

stood up as if wrought in silver, and the green before the dūn was a sheet of

unbroken white, save that in one place a scullion had killed a calf for their

dinner, and the blood of the calf lay on the snow. And as Deirdre looked, a

raven lit down from a tree hard by and began to sip the blood. “O nurse,” cried

Deirdre suddenly, “such, and not like Conor, would be the man that I would love

— his hair like the raven’s wing, and in his cheek the hue of blood, and his

skin as white as snow.” “Thou hast pictured a man of Conor’s household,” said

the nurse. “Who is he?” asked Deirdre. “He is Naisi, son of Usna,10

a champion of the Red Branch,” said the nurse. Thereupon Deirdre entreated

Levarcam to bring her to speak with Naisi; and because the old woman loved the

girl and would not have her wedded to the aged king, she at last agreed.

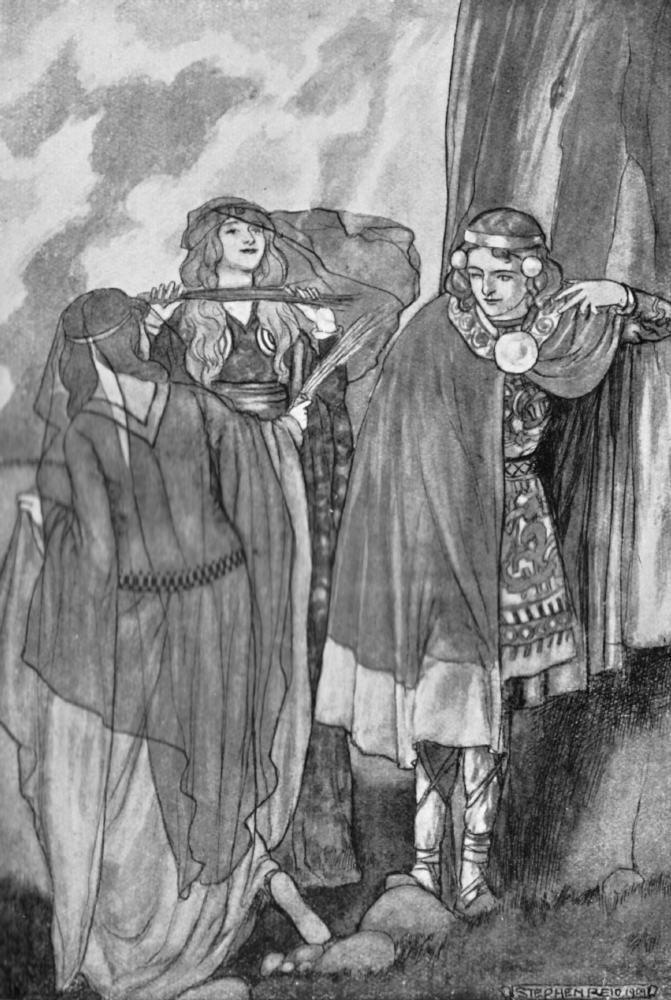

Deirdre implored Naisi to save her from Conor, but he would not, till at last

her entreaties and her beauty won him, and he vowed to be hers. Then secretly one

night he came with his two brethren, Ardan and Ainlé, and bore away Deirdre

with Levarcam, and they escaped the king’s pursuit and took ship for Scotland,

where Naisi took service with the King of the Picts. Yet here they could not

rest, for the king got sight of Deirdre, and would have taken her from Naisi,

but Naisi with his brothers escaped, and in the solitude of Glen Etive they

made their dwelling by the lake, and there lived in the wild wood by hunting

and fishing, seeing no man but themselves and their servants. And

the years went by and Conor made no sign, but he did not forget, and his spies

told him of all that befell Naisi and Deirdre. At last, judging that Naisi and his

brothers would have tired of solitude, he sent the bosom friend of Naisi,

Fergus son of Roy, to bid them return, and to promise them that all would be

forgiven. Fergus went joyfully, and joyfully did Naisi and his brothers hear

the message, but Deirdre foresaw evil, and would fain have sent Fergus home

alone. But Naisi blamed her for her doubt and suspicion, and bade her mark that

they were under the protection of Fergus, whose safeguard no king in Ireland

would dare to violate; and they at last made ready to go. On

landing in Ireland they were met by Baruch, a lord of the Red Branch, who had

his dūn close by, and he bade Fergus to a feast he had prepared for him that

night. “I may not stay,” said Fergus, “for I must first convey Deirdre and the

sons of Usna safely to Emain Macha.” “Nevertheless,” said Baruch, “thou must

stay with me to-night, for it is a geis

for thee to refuse a feast.” Deirdre implored him not to leave them, but Fergus

was tempted by the feast, and feared to break his geis, and he bade his two sons Illan the Fair and Buino the Red

take charge of the party in his place, and he himself abode with Baruch. And

so the party came to Emain Macha, and they were lodged in the House of the Red

Branch, but Conor did not receive them. After the evening meal, as he sat,

drinking heavily and silently, he sent a messenger to bid Levarcam come before

him. “How is it with the sons of Usna?” he said to her. “It is well,” she said.

“Thou hast got the three most valorous champions in Ulster in thy court. Truly

the king who has those three need fear no enemy.” “Is it well with Deirdre?” he

asked. “She is well,” said the nurse, “but she has lived many years in the

wildwood, and toil and care have changed her — little of her beauty of old now

remains to her, O King.” Then the king dismissed her, and sat drinking again.

But after a while he called to him a servant named Trendorn, and bade him go to

the Red Branch House and mark who was there and what they did. But when

Trendorn came the place was bolted and barred for the night, and he could not

get an entrance, and at last he mounted on a ladder and looked in at a high window.

And there he saw the brothers of Naisi and the sons of Fergus, as they talked

or cleaned their arms, or made them ready for slumber, and there sat Naisi with

a chess-board before him, and playing chess with him was the fairest of women

that he had ever seen. But as he looked in wonder at the noble pair, suddenly

one caught sight of him and rose with a cry, pointing to the face at the

window. And Naisi looked up and saw it, and seizing a chessman from the board

he hurled it at the face of the spy, and it struck out his eye. Then Trendorn

hastily descended, and went back with his bloody face to the king. “I have seen

them,” he cried, “I have seen the fairest woman of the world, and but that

Naisi had struck my eye out I had been looking on her still.” Then

Conor arose and called for his guards and bade them bring the sons of Usna

before him for maiming his messenger. And the guards went; but first Buino, son

of Fergus, with his retinue, met them, and at the sword’s point drove them

back; but Naisi and Deirdre continued quietly to play chess, “For,” said Naisi,

“it is not seemly that we should seek to defend ourselves while we are under

the protection of the sons of Fergus.” But Conor went to Buino, and with a

great gift of lands he bought him over to desert his charge. Then Illan took up

the defence of the Red Branch Hostel, but the two sons of Conor slew him. And

then at last Naisi and his brothers seized their weapons and rushed amid the

foe, and many were they who fell before the onset. Then Conor entreated Cathbad

the Druid to cast spells upon them lest they should get away and become the

enemies of the province, and he vowed to do them no hurt if they were taken

alive. So Cathbad conjured up, as it were, a lake of slime that seemed to be

about the feet of the sons of Usna, and they could not tear their feet from it,

and Naisi caught up Deirdre and put her on his shoulder, for they seemed to be

sinking in the slime. Then the guards and servants of Conor seized and bound

them and brought them before the king. And the king called upon man after man

to come forward and slay the sons of Usna, but none would obey him, till at

last Owen son of Duracht and Prince of Ferney came and took the sword of Naisi,

and with one sweep he shore off the heads of all three, and so they died. Then

Conor took Deirdre perforce, and for a year she abode with him in the palace in

Emain Macha, but during all that time she never smiled. At length Conor said:

“What is it that you hate most of all on earth, Deirdre?” And she said: “Thou

thyself and Owen son of Duracht,” and Owen was standing by. “Then thou shalt go

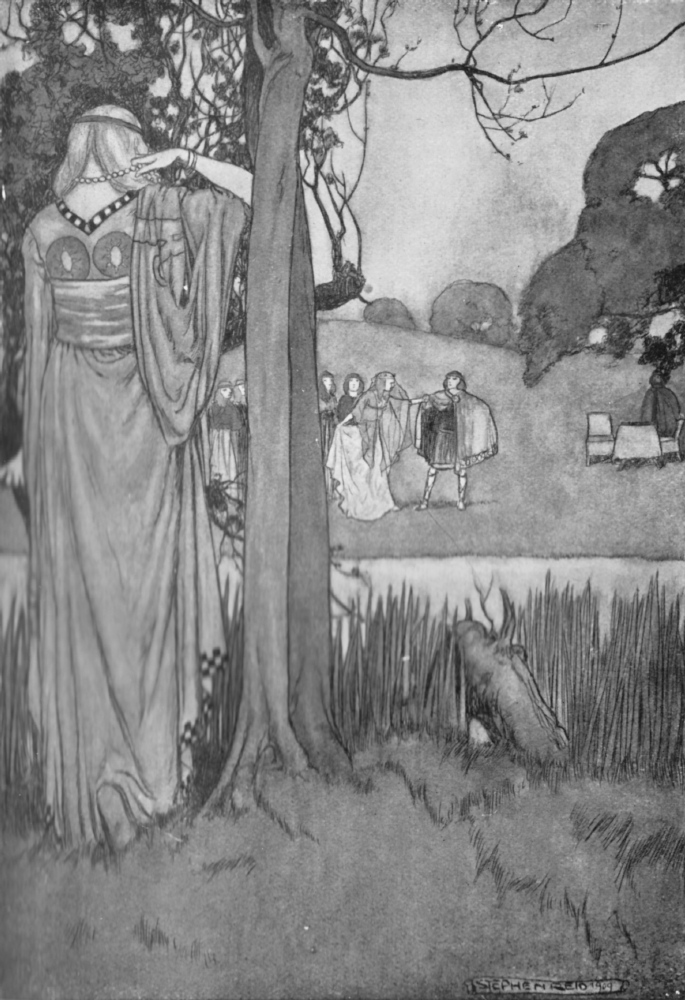

to Owen for a year,” said Conor. But when Deirdre mounted the chariot behind

Owen she kept her eyes on the ground, for she would not look on those who thus

tormented her; and Conor said, taunting her: “Deirdre, the glance of thee

between me and Owen is the glance of a ewe between two rams.” Then Deirdre

started up, and, flinging herself head foremost from the chariot, she dashed

her head against a rock and fell dead. And

when they buried her it is said there grew from her grave and from Naisi’s two

yew-trees, whose tops, when they were full-grown, met each other over the roof

of the great church of Armagh, and intertwined together, and none could part

them. The Rebellion of Fergus

When

Fergus mac Roy came home to Emain Macha after the feast to which Baruch bade

him and found the sons of Usna slain and one of his own sons dead and the other

a traitor, he broke out against Conor in a storm of wrath and cursing, and

vowed to be avenged on him with fire and sword. And he went off straightway to

Connacht to take service of arms with Ailell and Maev, who were king and queen

of that country. Queen Maev

But

though Ailell was king, Maev was the ruler in truth, and ordered all things as

she wished, and took what husbands she wished, and dismissed them at pleasure;

for she was as fierce and strong as a goddess of war, and knew no law but her

own wild will. She was tall, it is said, with a long, pale face and masses of

hair yellow as ripe corn. When Fergus came to her in her palace at Rathcroghan

in Roscommon she gave him her love, as she had given it to many before, and

they plotted together how to attack and devastate the Province of Ulster. The Brown Bull of Quelgny

Now

it happened that Maev possessed a famous red bull with white front and horns

named Finnbenach, and one day when she and Ailell were counting up their

respective possessions and matching them against each other he taunted her

because the Finnbenach would not stay in the hands of a woman, but had attached

himself to Ailell’s herd. So Maev in vexation went to her steward, mac Roth,

and asked of him if there were anywhere in Erin a bull as fine as the

Finnbenach. “Truly,” said the steward, “there is — for the Brown Bull of

Quelgny, that belongs to Dara son of Fachtna, is the mightiest beast that is in

Ireland.” And after that Maev felt as if she had no flocks and herds that were

worth anything at all unless she possessed the Brown Bull of Quelgny. But this

was in Ulster, and the Ulstermen knew the treasure they possessed, and Maev

knew that they would not give up the bull without fighting for it. So she and

Fergus and Ailell agreed to make a foray against Ulster for the Brown Bull, and

thus to enter into war with the province, for Fergus longed for vengeance, and Maev

for fighting, for glory, and for the bull, and Ailell to satisfy Maev. Here

let us note that this contest for the bull, which is the ostensible theme of

the greatest of Celtic legendary tales, the “Tain Bo Cuailgné,” has a deeper

meaning than appears on the surface. An ancient piece of Aryan mythology is

embedded in it. The Brown Bull is the Celtic counterpart of the Hindu

sky-deity, Indra, represented in Hindu myth as a mighty bull, whose roaring is

the thunder and who lets loose the rains “like cows streaming forth to

pasture.” The advance of the Western (Connacht) host for the capture of this

bull is emblematic of the onset of Night. The bull is defended by the solar

hero Cuchulain, who, however, is ultimately overthrown and the bull is captured

for a season. The two animals in the Celtic legend probably typify the sky in different

aspects. They are described with a pomp and circumstance which shows that they

are no common beasts. Once, we are told, they were swineherds of the people of Dana.

“They had been successively transformed into two ravens, two sea-monsters, two

warriors, two demons, two worms or animalculae, and finally into two kine.”11

The Brown Bull is described as having a back broad enough for fifty children to

play on; when he is angry with his keeper he stamps the man thirty feet into

the ground; he is likened to a sea wave, to a bear, to a dragon, a lion, the

writer heaping up images of strength and savagery. We are therefore concerned

with no ordinary cattle-raid, but with a myth, the features of which are

discernible under the dressing given it by the fervid imagination of the

unknown Celtic bard who composed the “Tain,” although the exact meaning of

every detail may be difficult to ascertain.

The

first attempt of Maev to get possession of the bull was to send an embassy to

Dara to ask for the loan of him for a year, the recompense offered being fifty

heifers, besides the bull himself back, and if Dara chose to settle in Connacht

he should have as much land there as he now possessed in Ulster, and a chariot

worth thrice seven umals,12 with the patronage and friendship

of Maev. Dara

was at first delighted with the prospect, but tales were borne to him of the

chatter of Maev’s messengers, and how they said that if the bull was not

yielded willingly it would be taken by force; and he sent back a message of

refusal and defiance. “’Twas known,” said Maev, “the bull will not be yielded

by fair means; he shall now be won by foul.” And so she sent messengers around

on every side to summon her hosts for the Raid.

The Hosting of Queen Maev

And

there came all the mighty men of Connacht — first the seven Mainés, sons of

Ailell and Maev, each with his retinue; and Ket and Anluan, sons of Maga, with

thirty hundreds of armed men; and yellow-haired Ferdia, with his company of

Firbolgs, boisterous giants who delighted in war and in strong ale. And there

came also the allies of Maev — a host of the men of Leinster, who so excelled

the rest in warlike skill that they were broken up and distributed among the

companies of Connacht, lest they should prove a danger to the host; and Cormac

son of Conor, with Fergus mac Roy and other exiles from Ulster, who had

revolted against Conor for his treachery to the sons of Usna. Ulster under the Curse

But

before the host set forth towards Ulster Maev sent her spies into the land to

tell her of the preparations there being made. And the spies brought back a

wondrous tale, and one that rejoiced the heart of Maev, for they said that the

Debility of the Ultonians13 had descended on the province. Conor the

king lay in pangs at Emain Macha, and his son Cuscrid in his island-fortress,

and Owen Prince of Ferney was helpless as a child; Celtchar, the huge grey

warrior, son of Uthecar Hornskin, and even Conall of the Victories, lay moaning

and writhing on their beds, and there was no hand in Ulster that could lift a

spear.  Prophetic Voices

Nevertheless

Maev went to her chief Druid, and demanded of him what her own lot in the war

should be. And the Druid said only: “Whoever comes hack in safety, or comes not,

thou thyself shalt come.” But on her journey back she saw suddenly standing

before her chariot-pole a young maiden with tresses of yellow hair that fell

below her knees, and clad in a mantle of green; and with a shuttle of gold she

wove a fabric upon a loom. “Who art thou, girl?” said Maev, “and what dost

thou?” “I am the prophetess, Fedelma, from the Fairy Mound of Croghan,” said

the maid, “and I weave the four provinces of Ireland together for the foray

into Ulster.” “How seest thou our host?” asked Maev. “I see them all

be-crimsoned, red,” replied the prophetess. “Yet the Ulster heroes are all in

their pangs — there is none that can lift a spear against us,” said Maev. “I

see the host all becrimsoned,” said Fedelma. “I see a man of small stature, but

the hero’s light is on his brow — a stripling young and modest, but in battle a

dragon; he is like unto Cuchulain of Murthemney; he doth wondrous feats with

his weapons; by him your slain shall lie thickly.”14 At

this the vision of the weaving maiden vanished, and Maev drove homewards to

Rathcroghan wondering at what she had seen and heard. Cuchulain Puts the Host under Geise

On

the morrow the host set forth, Fergus mac Roy leading them, and as they neared

the confines of Ulster he bade them keep sharp watch lest Cuchulain of

Murthemney, who guarded the passes of Ulster to the south, should fall upon

them unawares. Now Cuchulain and his father Sualtam15 were on the borders

of the province, and Cuchulain, from a warning Fergus had sent him, suspected

the approach of a great host, and bade Sualtam go northwards to Emania and warn

the men of Ulster. But Cuchulain himself would not stay there, for he said he

had a tryst to keep with a handmaid of the wife of Laery the bodach

(farmer), so he went into the forest, and there, standing on one leg, and using

only one hand and one eye, he cut an oak sapling and twisted it into a circular

withe. On this he cut in Ogham characters how the withe was made, and he put

the host of Maev under geise not to

pass by that place till one of them had, under similar conditions, made a

similar withe; “and I except my friend Fergus mac Roy,” he added, and wrote his

name at the end. Then he placed the withe round the pillar-stone of Ardcullin,

and went his way to keep his tryst with the handmaid.16 When

the host of Maev came to Ardcullin, the withe upon the pillar-stone was found

and brought to Fergus to decipher it. There was none amongst the host who could

emulate the feat of Cuchulain, and so they went into the wood and encamped for

the night. A heavy snowfall took place, and they were all in much distress, but

next day the sun rose gloriously, and over the white plain they marched away

into Ulster, counting the prohibition as extending only for one night. The Ford of the Forked Pole

Cuchulain

now followed hard on their track, and as he went he estimated by the tracks

they had left the number of the host at eighteen triucha cét (54,000

men). Circling round the host, he now met them in front, and soon came upon two

chariots containing scouts sent ahead by Maev. These he slew, each man with his

driver, and having with one sweep of his sword cut a forked pole of four prongs

from the wood, he drove the pole deep into a river-ford at the place called

Athgowla,17 and impaled on each prong a bloody head. When the host

came up they wondered and feared at the sight, and Fergus declared that they

were under geise not to pass that

ford till one of them had plucked out the pole even as it was driven in, with the

fingertips of one hand. So Fergus drove into the water to essay the feat, and

seventeen chariots were broken under him as he tugged at the pole, but at last

he tore it out; and as it was now late the host encamped upon the spot. These

devices of Cuchulain were intended to delay the invaders until the Ulster men

had recovered from their debility. In

the epic, as given in the Book of Leinster, and other ancient sources, a long

interlude now takes place in which Fergus explains to Maev who it is — viz.,

“my little pupil Setanta” — who is thus harrying the host, and his boyish

deeds, some of which have been already told in this narrative, are recounted. The Charioteer of Orlam

The

host proceeded on its way next day, and the next encounter with Cuchulain shows

the hero in a kindlier mood. He hears a noise of timber being cut, and going

into a wood he finds there a charioteer belonging to a son of Ailell and Maev

cutting down chariot-poles of holly, “For,” says he, “we have damaged our

chariots sadly in chasing that famous deer, Cuchulain.” Cuchulain — who, it

must be remembered, was at ordinary times a slight and unimposing figure,

though in battle he dilated in size and underwent a fearful distortion,

symbolic of Berserker fury — helps the driver in his work. “Shall I,” he asks,

“cut the poles or trim them for thee?” “Do thou the trimming,” says the driver.

Cuchulain takes the poles by the tops and draws them against the set of the

branches through his toes, and then runs his fingers down them the same way,

and gives them over as smooth and polished as if they were planed by a

carpenter. The driver stares at him. “I doubt this work I set thee to is not

thy proper work,” he says. “Who art thou then at all?” “I am that Cuchulain of

whom thou spakest but now.” “Surely I am but a dead man,” says the driver.

“Nay,” replies Cuchulain, “I slay not drivers nor messengers nor men unarmed.

But run, tell thy master Orlam that Cuchulain is about to visit him.” The

driver runs off, but Cuchulain outstrips him, meets Orlam first, and strikes

off his head. For a moment the host of Maev see him as he shakes this bloody

trophy before them; then he disappears from sight — it is the first glimpse

they have caught of their persecutor.  J. C. Leyendecker The Battle-Frenzy of Cuchulain

A

number of scattered episodes now follow. The host of Maev spreads out and

devastates the territories of Bregia and of Murthemney, but they cannot advance

further into Ulster. Cuchulain hovers about them continually, slaying them by

twos and threes, and no man knows where he will swoop next. Maev herself is

awed when, by the bullets of an unseen slinger, a squirrel and a pet bird are

killed as they sit upon her shoulders. Afterwards, as Cuchulain’s wrath grows

fiercer, he descends with supernatural might upon whole companies of the

Connacht host, and hundreds fall at his onset. The characteristic distortion or

riastradh which seized him in his battle-frenzy is then described. He

became a fearsome and multiform creature such as never was known before. Every particle

of him quivered like a bulrush in a running stream. His calves and heels and

hams shifted to the front, and his feet and knees to the back, and the muscles

of his neck stood out like the head of a young child. One eye was engulfed deep

in his head, the other protruded, his mouth met his ears, foam poured from his

jaws like the fleece of a three-year-old wether. The beats of his heart sounded

like the roars of a lion as he rushes on his prey. A light blazed above his

head, and “his hair became tangled about as it had been the branches of a red

thorn-bush stuffed into the gap of a fence.... Taller, thicker, more rigid,

longer than the mast of a great ship was the perpendicular jet of dusky blood which

out of his scalp’s very central point shot upwards and was there scattered to

the four cardinal points, whereby was formed a magic mist of gloom resembling

the smoky pall that drapes a regal dwelling, what time a king at nightfall of a

winter’s day draws near to it.”18

Such

was the imagery by which Gaelic writers conveyed the idea of superhuman frenzy.

At the sight of Cuchulain in his paroxysm it is said that once a hundred of

Maev’s warriors fell dead from horror. The Compact of the Ford

Maev

now tried to tempt him by great largesse to desert the cause of Ulster, and had

a colloquy with him, the two standing on opposite sides of a glen across which

they talked. She scanned him closely, and was struck by his slight and boyish

appearance. She failed to move him from his loyalty to Ulster, and death

descends more thickly than ever upon the Connacht host; the men are afraid to

move out for plunder save in twenties and thirties, and at night the stones

from Cuchulain’s sling whistle continually through the camp, braining or

maiming. At last, through the mediation of Fergus, an agreement was come to.

Cuchulain undertook not to harry the host provided they would only send against

him one champion at a time, whom Cuchulain would meet in battle at the ford of

the River Dee, which is now called the Ford of Ferdia.19 While each

fight was in progress the host might move on, but when it was ended they must

encamp till the morrow morning. “Better to lose one man a day than a hundred,” said

Maev, and the pact was made. Fergus and Cuchulain

Several

single combats are then narrated, in which Cuchulain is always a victor. Maev

even persuades Fergus to go against him, but Fergus and Cuchulain will on no

account fight each other, and Cuchulain, by agreement with Fergus, pretends to

fly before him, on Fergus’s promise that he will do the same for Cuchulain when

required. How this pledge was kept we shall see later. Capture of the Brown Bull

During

one of Cuchulain’s duels with a famous champion, Natchrantal, Maev, with a

third of her army, makes a sudden foray into Ulster and penetrates as far as

Dunseverick, on the northern coast, plundering and ravaging as they go. The

Brown Bull, who was originally at Quelgny (Co. Down), has been warned at an

earlier stage by the Morrigan20 to withdraw himself, and he has

taken refuge, with his herd of cows, in a glen of Slievegallion, Co. Armagh.

The raiders of Maev find him there, and drive him off with the herd in triumph,

passing Cuchulain as they return. Cuchulain slays the leader of the escort — Buic

son of Banblai — but cannot rescue the Bull, and “this,” it is said, “was the

greatest affront put on Cuchulain during the course of the raid.” The Morrigan

The

raid ought now to have ceased, for its object has been attained, but by this

time the hostings of the four southern provinces21 had gathered together

under Maev for the plunder of Ulster, and Cuchulain remained still the solitary

warder of the marches. Nor did Maev keep her agreement, for bands of twenty warriors

at a time were loosed against him and he had much ado to defend himself. The

curious episode of the fight with the Morrigan now occurs. A young woman clad

in a mantle of many colours appears to Cuchulain, telling him that she is a

king’s daughter, attracted by the tales of his great exploits, and she has come

to offer him her love. Cuchulain tells her rudely that he is worn and harassed

with war and has no mind to concern himself with women. “It shall go hard with

thee,” then said the maid, “when thou hast to do with men, and I shall be about

thy feet as an eel in the bottom of the Ford.” Then she and her chariot vanished

from his sight and he saw but a crow sitting on a branch of a tree, and he knew

that he had spoken with the Morrigan. The Fight with Loch

The

next champion sent against him by Maev was Loch son of Mofebis. To meet this

hero it is said that Cuchulain had to stain his chin with blackberry juice so

as to simulate a beard, lest Loch should disdain to do combat with a boy. So

they fought in the Ford, and the Morrigan came against him in the guise of a

white heifer with red ears, but Cuchulain fractured her eye with a cast of his

spear. Then she came swimming up the river like a black eel and twisted herself

about his legs, and ere he could rid himself of her Loch wounded him. Then she

attacked him as a grey wolf, and again, before he could subdue her, he was

wounded by Loch. At this his battle-fury took hold of him and he drove the Gae

Bolg against Loch, splitting his heart in two. “Suffer me to rise,” said Loch,

“that I may fall on my face on thy side of the ford, and not backward toward

the men of Erin.” “It is a warrior’s boon thou askest,” said Cuchulain, “and it

is granted.” So Loch died; and a great despondency, it is said, now fell upon

Cuchulain, for he was outwearied with continued fighting, and sorely wounded,

and he had never slept since the beginning of the raid, save leaning upon his

spear; and he sent his charioteer, Laeg, to see if he could rouse the men of

Ulster to come to his aid at last. Lugh the Protector

But

as he lay at evening by the grave mound of Lerga in gloom and dejection,

watching the camp-fires of the vast army encamped over against him and the

glitter of their innumerable spears, he saw coming through the host a tall and

comely warrior who strode impetuously forward, and none of the companies

through which he passed turned his head to look at him or seemed to see him. He

wore a tunic of silk embroidered with gold, and a green mantle fastened with a

silver brooch; in one hand was a black shield bordered with silver and two

spears in the other. The stranger came to Cuchulain and spoke gently and

sweetly to him of his long toil and waking, and his sore wounds, and said in

the end: “Sleep now, Cuchulain, by the grave in Lerga; sleep and slumber deeply

for three days, and for that time I will take thy place and defend the Ford

against the host of Maev.” Then Cuchulain sank into a profound slumber and

trance, and the stranger laid healing balms of magical power to his wounds so

that he awoke whole and refreshed, and for the time that Cuchulain slept the

stranger held the Ford against the host. And Cuchulain knew that this was Lugh

his father, who had come from among the People of Dana to help his son through

his hour of gloom and despair. The Sacrifice of the Boy Corps

But

still the men of Ulster lay helpless. Now there was at Emain Macha a band of

thrice fifty boys, the sons of all the chieftains of the provinces, who were

there being bred up in arms and in noble ways, and these suffered not from the

curse of Macha, for it fell only on grown men. But when they heard of the sore

straits in which Cuchulain, their playmate not long ago, was lying they put on

their light armour and took their weapons and went forth for the honour of

Ulster, under Conor’s young son, Follaman, to aid him. And Follaman vowed that

he would never return to Emania without the diadem of Ailell as a trophy. Three

times they drove against the host of Maev, and thrice their own number fell

before them, but in the end they were overwhelmed and slain, not one escaping

alive. The Carnage of Murthemney

This

was done as Cuchulain lay in his trance, and when he awoke, refreshed and well,

and heard what had been done, his frenzy came upon him and he leaped into his

war-chariot and drove furiously round and round the host of Maev. And the

chariot ploughed the earth till the ruts were like the ramparts of a fortress,

and the scythes upon its wheels caught and mangled the bodies of the crowded

host till they were piled like a wall around the camp, and as Cuchulain shouted

in his wrath the demons and goblins and wild things in Erin yelled in answer,

so that with the terror and the uproar the host of men heaved and surged hither

and thither, and many perished from each other’s weapons, and many from horror

and fear. And this was the great carnage, called the Carnage of Murthemney,

that Cuchulain did to avenge the boy-corps of Emania; six score and ten princes

were then slain of the host of Maev, besides horses and women and wolf-dogs and

common folk without number. It is said that Lugh mac Ethlinn fought there by

his son. The Clan Calatin

Next

the men of Erin resolved to send against Cuchulain, in single combat, the Clan

Calatin.22 Now Calatin was a wizard, and he and his seven-and-twenty

sons formed, as it were, but one being, the sons being organs of their father,

and what any one of them did they all did alike. They were all poisonous, so

that any weapon which one of them used would kill in nine days the man who was

but grazed by it. When this multiform creature met Cuchulain each hand of it

hurled a spear at once, but Cuchulain caught the twenty-eight spears on his

shield and not one of them drew blood. Then he drew his sword to lop off the

spears that bristled from his shield, but as he did so the Clan Calatin rushed

upon him and flung him down, thrusting his face into the gravel. At this

Cuchulain gave a great cry of distress at the unequal combat, and one of the

Ulster exiles, Fiacha son of Firaba, who was with the host of Maev, and was looking

on at the fight, could not endure to see the plight of the champion, and he

drew his sword and with one stroke he lopped off the eight-and-twenty hands

that were grinding the face of Cuchulain into the gravel of the Ford. Then

Cuchulain arose and hacked the Clan Calatin into fragments, so that none

survived to tell Maev what Fiacha had done, else had he and his thirty hundred

followers of Clan Rury been given by Maev to the edge of the sword. Ferdia to the Fray

Cuchulain

had now overcome all the mightiest of Maev’s men, save only the mightiest of

them all after Fergus, Ferdia son of Daman. And because Ferdia was the old

friend and fellow pupil of Cuchulain he had never gone out against him; but now

Maev begged him to go, and he would not. Then she offered him her daughter,

Findabair of the Fair Eyebrows, to wife, if he would face Cuchulain at the

Ford, but he would not. At last she bade him go, lest the poets and satirists

of Erin should make verses on him and put him to open shame, and then in wrath

and sorrow he consented to go, and bade his charioteer make ready for

to-morrow’s fray. Then was gloom among all his people when they heard of that,

for they knew that if Cuchulain and their master met, one of them would return

alive no more. Very

early in the morning Ferdia drove to the Ford, and lay down there on the

cushions and skins of the chariot and slept till Cuchulain should come. Not

till it was full daylight did Ferdia’s charioteer hear the thunder of

Cuchulain’s war-car approaching, and then he woke his master, and the two

friends faced each other across the Ford. And when they had greeted each other

Cuchulain said: “It is not thou, O Ferdia, who shouldst have come to do battle

with me. When we were with Skatha did

we not go side by side in every battle,

through every wood and wilderness? were we not heart-companions, comrades, in

the feast and the assembly? did we not share one bed and one deep slumber?” But

Ferdia replied: “O Cuchulain, thou of the wondrous feats, though we have

studied poetry and science together, and though I have heard thee recite our

deeds of friendship, yet it is my hand that shall wound thee. I bid thee

remember not our comradeship, O Hound of Ulster; it shall not avail thee, it

shall not avail thee.”  They

then debated with what weapons they should begin the fight, and Ferdia reminded

Cuchulain of the art of casting small javelins that they had learned from

Skatha, and they agreed to begin with these. Backwards and forwards, then,

across the Ford, hummed the light javelins like bees on a summer’s day, but

when noonday had come not one weapon had pierced the defence of either

champion. Then they took to the heavy missile spears, and now at last blood

began to flow, for each champion wounded the other time and again. At last the

day came to its close. “Let us cease now,” said Ferdia, and Cuchulain agreed.

Each then threw his arms to his charioteer, and the friends embraced and kissed

each other three times, and went to their rest. Their horses were in the same

paddock, their drivers warmed themselves over the same fire, and the heroes

sent each other food and drink and healing herbs for their wounds. Next

day they betook themselves again to the Ford, and this time, because Ferdia had

the choice of weapons the day before, he bade Cuchulain take it now.23

Cuchulain chose then the heavy, broad-bladed spears for close fighting, and

with them they fought from the chariots till the sun went down, and drivers and

horses were weary, and the body of each hero was torn with wounds. Then at last

they gave over, and threw away their weapons. And they kissed each other as

before, and as before they shared all things at night, and slept peacefully

till the morning. When

the third day of the combat came Ferdia wore an evil and lowering look, and

Cuchulain reproached him for coming out in battle against his comrade for the

bribe of a fair maiden, even Findabair, whom Maev had offered to every champion

and to Cuchulain himself if the Ford might be won thereby; but Ferdia said:

“Noble Hound, had I not faced thee when summoned, my troth would be broken, and

there would be shame on me in Rathcroghan.” It is now the turn of Ferdia to

choose the weapons, and they betake themselves to their “heavy, hard-smiting

swords,” and though they hew from each other’s thighs and shoulders great

cantles of flesh, neither can prevail over the other, and at last night ends the

combat. This time they parted from each other in heaviness and gloom, and there

was no interchange of friendly acts, and their drivers and horses slept apart. The

passions of the warriors had now risen to a grim sternness. Death of Ferdia

On

the fourth day Ferdia knew the contest would be decided, and he armed himself

with especial care. Next his skin was a tunic of striped silk bordered with

golden spangles, and over that hung an apron of brown leather. Upon his belly

he laid a flat stone, large as a millstone, and over that a strong, deep apron

of iron, for he dreaded that Cuchulain would use the Gae Bolg that day. And he

put on his head his crested helmet studded with carbuncle and inlaid with

enamels, and girt on his golden-hilted sword, and on his left arm hung his

broad shield with its fifty bosses of bronze. Thus he stood by the Ford, and as

he waited he tossed up his weapons and caught them again and did many wonderful

feats, playing with his mighty weapons as a juggler plays with apples; and Cuchulain,

watching him, said to Laeg, his driver: “If I give ground to-day, do thou

reproach and mock me and spur me on to valour, and praise and hearten me if I

do well, for I shall have need of all my courage.” “O

Ferdia,” said Cuchulain when they met, “what shall be our weapons to-day?” “It

is thy choice to-day,” said Ferdia. “Then let it be all or any,” said

Cuchulain, and Ferdia was cast down at hearing this, but he said, “So be it,”

and thereupon the fight began. Till midday they fought with spears, and none

could gain any advantage over the other. Then Cuchulain drew his sword and

sought to smite Ferdia over the rim of his shield; but the giant Firbolg flung

him off. Thrice Cuchulain leaped high into the air, seeking to strike Ferdia

over his shield, but each time as he descended Ferdia caught him upon the

shield and flung him off like a little child into the Ford. And Laeg mocked

him, crying: “He casts thee off as a river flings its foam, he grinds thee as a

millstone grinds a corn of wheat; thou elf, never call thyself a warrior.” Then

at last Cuchulain’s frenzy came upon him, and he dilated giant-like, till he

overtopped Ferdia, and the hero-light blazed about his head. In close contact

the two were interlocked, whirling and trampling, while the demons and goblins

and unearthly things of the glens screamed from the edges of their swords, and

the waters of the Ford recoiled in terror from them, so that for a while they

fought on dry land in the midst of the riverbed. And now Ferdia found Cuchulain

a moment off his guard, and smote him with the edge of the sword, and it sank

deep into his flesh, and all the river ran red with his blood. And he pressed

Cuchulain sorely after that, hewing and thrusting so that Cuchulain could

endure it no longer, and he shouted to Laeg to fling him the Gae Bolg. When

Ferdia heard that he lowered his shield to guard himself from below, and

Cuchulain drove his spear over the rim of the shield and through his

breastplate into his chest. And Ferdia raised his shield again, but in that

moment Cuchulain seized the Gae Bolg in his toes and drove it upward against

Ferdia, and it pierced through the iron apron and burst in three the millstone

that guarded him, and deep into his body it passed, so that every crevice and cranny

of him was filled with its barbs. “’Tis enough,” cried Ferdia; “I have my death

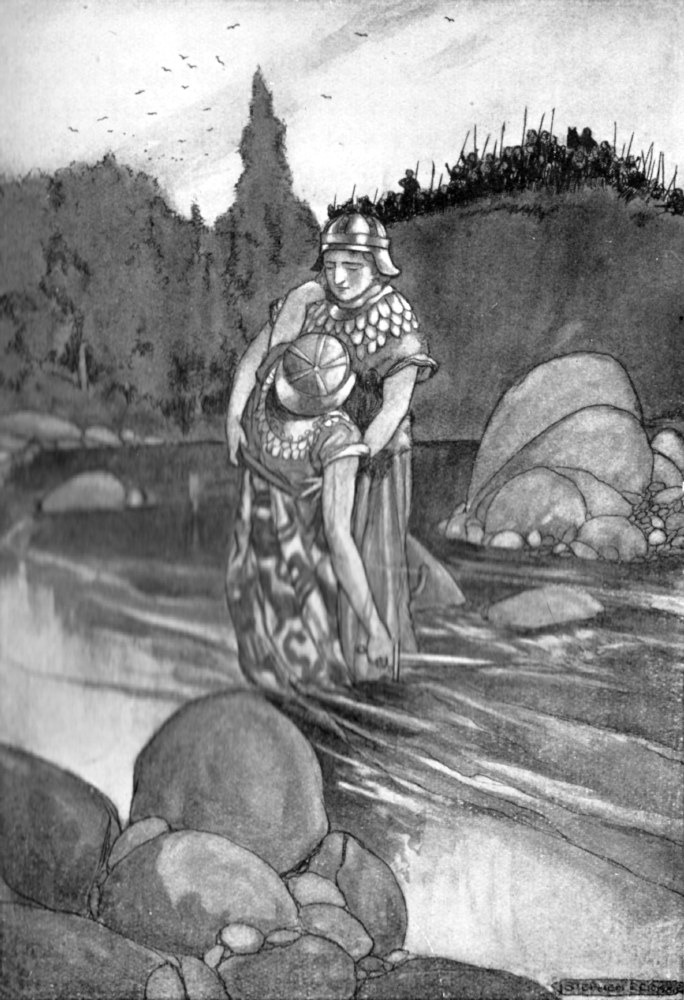

of that. It is an ill deed that I fall by thy hand, O Cuchulain.” Cuchulain

seized him as he fell, and carried him northward across the Ford, that he might

die on the further side of it, and not on the side of the men of Erin. Then he

laid him down, and a faintness seized Cuchulain, and he was falling, when Laeg

cried: “Rise up, Cuchulain, for the host of Erin will be upon us. No single

combat will they give after Ferdia has fallen.” But Cuchulain said: “Why should

I rise again, O my servant, now he that lieth here has fallen by my hand?” and

he fell in a swoon like death. And the host of Maev with tumult and rejoicing,

with tossing of spears and shouting of war-songs, poured across the border into

Ulster. But

before they left the Ford they took the body of Ferdia and laid it in a grave,

and built a mound over him and set up a pillar-stone with his name and lineage

in Ogham. And from Ulster came certain of the friends of Cuchulain, and they

bore him away into Murthemney, where they washed him and bathed his wounds in

the streams, and his kin among the Danaan folk cast magical herbs into the

rivers for his healing. But he lay there in weakness and in stupor for many

days. The Rousing of Ulster

Now

Sualtam, the father of Cuchulain, had taken his son’s horse, the Grey of Macha,

and ridden off again to see if by any means he might rouse the men of Ulster to

defend the province. And he went crying abroad: “The men of Ulster are being

slain, the women carried captive, the kine driven!” Yet they stared on him

stupidly, as though they knew not of what he spake. At last he came to Emania,

and there were Cathbad the Druid and Conor the King, and all their nobles and

lords, and Sualtam cried aloud to them: “The men of Ulster are being slain, the

women carried captive, the kine driven; and Cuchulain alone holds the gap of

Ulster against the four provinces of Erin. Arise and defend yourselves!” But

Cathbad only said: “Death were the due of him who thus disturbs the King”; and

Conor said: “Yet it is true what the man says”; and the lords of Ulster wagged

their heads and murmured: “True indeed it is.”

Then

Sualtam wheeled round his horse in anger and was about to depart when, with a

start which the Grey made, his neck fell against the sharp rim of the shield

upon his back, and it shore off his head, and the head fell on the ground. Yet

still it cried its message as it lay, and at last Conor bade put it on a pillar

that it might be at rest. But it still went on crying and exhorting, and at

length into the clouded mind of the king the truth began to penetrate, and the

glazed eyes of the warriors began to glow, and slowly the spell of Macha’s

curse was lifted from their minds and bodies. Then Conor arose and swore a

mighty oath, saying: “The heavens are above us and the earth beneath us, and

the sea is round about us; and surely, unless the heavens fall on us and the

earth gape to swallow us up, and the sea overwhelm the earth, I will restore every

woman to her hearth, and every cow to its byre.”24 His Druid

proclaimed that the hour was propitious, and the king bade his messengers go

forth on every side and summon Ulster to arms, and he named to them warriors