| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Myths & Legends: The Celtic Race Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IV: THE EARLY MILESIAN KINGS The Danaans after the Milesian

Conquest

The

kings and heroes of the Milesian race now fill the foreground of the stage in

Irish legendary history. But, as we have indicated, the Danaan divinities are

by no means forgotten. The fairyland in which they dwell is ordinarily

inaccessible to mortals, yet it is ever near at hand; the invisible barriers

may be, and often are, crossed by mortal men, and the Danaans themselves

frequently come forth from them; mortals may win brides of Faëry who

mysteriously leave them after a while, and women bear glorious children of

supernatural fatherhood. Yet whatever the Danaans may have been in the original

pre-Christian conceptions of the Celtic Irish, it would be a mistake to suppose

that they figure in the legends, as these have now come down to us, in the

light of gods as we understand this term. They are for the most part radiantly

beautiful, they are immortal (with limitations), and they wield mysterious

powers of sorcery and enchantment. But no sort of moral governance of the world

is ever for a moment ascribed to them, nor (in the bardic literature) is any

act of worship paid to them. They do not die naturally, but they can be slain

both by each other and by mortals, and on the whole the mortal race is the

stronger. Their strength when they come into conflict (as frequently happens)

with men lies in stratagem and illusion; when the issue can be fairly knit

between the rival powers it is the human that conquers. The early kings and

heroes of the Milesian race are, indeed, often represented as so mightily

endowed with supernatural power that it is impossible to draw a clear

distinction between them and the People of Dana in this respect. The Danaans

are much nobler and more exalted beings, as they figure in the bardic

literature, than the fairies into which they ultimately degenerated in the popular

imagination; they may be said to hold a position intermediate between these and

the Greek deities as portrayed in Homer. But the true worship of the Celts, in

Ireland as elsewhere, seems to have been paid, not to these poetical

personifications of their ideals of power and beauty, but rather to elemental

forces represented by actual natural phenomena — rocks, rivers, the sun, the

wind, the sea. The most binding of oaths was to swear by the Wind and Sun, or

to invoke some other power of nature; no name of any Danaan divinity occurs in

an Irish oath formula. When, however, in the later stages of the bardic

literature, and still more in the popular conceptions, the Danaan deities had

begun to sink into fairies, we find rising into prominence a character probably

older than that ascribed to them in the literature, and, in a way, more august.

In the literature it is evident that they were originally representatives of

science and poetry — the intellectual powers of man. But in the popular mind

they represented, probably at all times and certainly in later Christian times,

not intellectual powers, but those associated with the fecundity of earth. They

were, as a passage in the Book of Armagh names them, dei terreni, earth-gods,

and were, and are still, invoked by the peasantry to yield increase and

fertility. The literary conception of them is plainly Druidic in origin, the

other popular; and the popular and doubtless older conception has proved the

more enduring. But

these features of Irish mythology will appear better in the actual tales than

in any critical discussion of them; and to the tales let us now return. The Milesian Settlement of Ireland

The

Milesians had three leaders when they set out for the conquest of Ireland — Eber

Donn (Brown Eber), Eber Finn (Fair Eber), and Eremon. Of these the first-named,

as we have seen, was not allowed to enter the land — he perished as a

punishment for his brutality. When the victory over the Danaans was secure the

two remaining brothers turned to the Druid Amergin for a judgment as to their

respective titles to the sovranty. Eremon was the elder of the two, but Eber

refused to submit to him. Thus Irish history begins, alas! with dissension and

jealousy. Amergin decided that the land should belong to Eremon for his life,

and pass to Eber after his death. But Eber refused to submit to the award, and

demanded an immediate partition of the new-won territory. This was agreed to,

and Eber took the southern half of Ireland, “from the Boyne to the Wave of Cleena,”1

while Eremon occupied the north. But even so the brethren could not be at

peace, and after a short while war broke out between them. Eber was slain, and

Eremon became sole King of Ireland, which he ruled from Tara, the traditional

seat of that central authority which was always a dream of the Irish mind, but

never a reality of Irish history. Tiernmas and Crom Cruach

Of

the kings who succeeded Eremon, and the battles they fought and the forests

they cleared away and the rivers and lakes that broke out in their reign, there

is little of note to record till we come to the reign of Tiernmas, fifth in

succession from Eremon. He is said to have introduced into Ireland the worship

of Crom Cruach, on Moyslaught (The Plain of Adoration2), and to have

perished himself with three-fourths of his people while worshipping this idol

on November Eve, the period when the reign of winter was inaugurated. Crom

Cruach was no doubt a solar deity, but no figure at all resembling him can be

identified among the Danaan divinities. Tiernmas also, it is said, found the

first gold-mine in Ireland, and introduced variegated colours into the clothing

of the people. A slave might wear but one colour, a peasant two, a soldier

three, a wealthy landowner four, a provincial chief five, and an Ollav, or

royal person, six. Ollav was a term applied to a certain Druidic rank; it meant

much the same as “doctor,” in the sense of a learned man — a master of science.

It is a characteristic trait that the Ollav is endowed with a distinction equal

to that of a king. Ollav Fōla

The

most distinguished Ollav of Ireland was also a king, the celebrated Ollav Fōla,

who is supposed to have been eighteenth from Eremon and to have reigned about

1000 B.C. He was the Lycurgus or Solon of Ireland, giving to the country a code

of legislature, and also subdividing it, under the High King at Tara, among the

provincial chiefs, to each of whom his proper rights and obligations were

allotted. To Ollav Fōla is also attributed the foundation of an institution

which, whatever its origin, became of great importance in Ireland — the great

triennial Fair or Festival at Tara, where the sub-kings and chiefs, bards,

historians, and musicians from all parts of Ireland assembled to make up the

genealogical records of the clan chieftainships, to enact laws, hear disputed

cases, settle succession, and so forth; all these political and legislative

labours being lightened by song and feast. It was a stringent law that at this season

all enmities must be laid aside; no man might lift his hand against another, or

even institute a legal process, while the Assembly at Tara was in progress. Of

all political and national institutions of this kind Ollav Fōla was regarded as

the traditional founder, just as Goban the Smith was the founder of artistry

and handicraft, and Amergin of poetry. But whether the Milesian king had any

more objective reality than the other more obviously mythical figures it is

hard to say. He is supposed to have been buried in the great tumulus at Loughcrew,

in Westmeath. Kimbay and the Founding of Emain

Macha

With

Kimbay (Cimbaoth), about 300 B.C., we come to a landmark in history.

“All the historical records of the Irish, prior to Kimbay, were dubious” — so,

with remarkable critical acumen for his age, wrote the eleventh-century

historian Tierna of Clonmacnois.3 There is much that is dubious in

those that follow, but we are certainly on firmer historical ground. With the

reign of Kimbay one great fact emerges into light: we have the foundation of

the kingdom of Ulster at its centre, Emain Macha, a name redolent to the Irish

student of legendary splendour and heroism. Emain Macha is now represented by

the grassy ramparts of a great hill-fortress close to Ard Macha (Armagh).

According to one of the derivations offered in Keating’s “History of Ireland,” Emain

is derived from eo, a bodkin, and muin, the neck, the word being

thus equivalent to “brooch,” and Emain Macha means the Brooch of Macha. An

Irish brooch was a large circular wheel of gold or bronze, crossed by a long

pin, and the great circular rampart surrounding a Celtic fortress might well be

imaginatively likened to the brooch or a giantess guarding her cloak, or territory.4

The legend of Macha tells that she was the daughter of Red Hugh, an Ulster

prince who had two brothers, Dithorba and Kimbay. They agreed to enjoy, each in

turn, the sovranty of Ireland. Red Hugh came first, but on his death Macha

refused to give up the realm and fought Dithorba for it, whom she conquered and

slew. She then, in equally masterful manner, compelled Kimbay to wed her, and

ruled all Ireland as queen. I give the rest of the tale in the words of

Standish O’Grady: “The

five sons of Dithorba, having been expelled out of Ulster, fled across the Shannon,

and in the west of the kingdom plotted against Macha. Then the Queen went down

alone into Connacht and found the brothers in the forest, where, wearied with

the chase, they were cooking a wild boar which they had slain, and were

carousing before a fire which they had kindled. She appeared in her grimmest

aspect, as the war-goddess, red all over, terrible and hideous as war itself

but with bright and flashing eyes. One by one the brothers were inflamed by her

sinister beauty, and one by one she overpowered and bound them. Then she lifted

her burthen of champions upon her back and returned with them into the north.

With the spear of her brooch she marked out on the plain the circuit of the

city of Emain Macha, whose ramparts and trenches were constructed by the

captive princes, labouring like slaves under her command.” “The

underlying idea of all this class of legend,” remarks Mr. O’Grady, “is that if

men cannot master war, war will master them; and that those who aspired to the

Ard-Rieship [High-Kingship] of all Erin must have the war-gods on their side.”5 Macha

is an instance of the intermingling of the attributes of the Danaan with the

human race of which I have already spoken.

Laery and Covac

The

next king who comes into legendary prominence is Ugainy the Great, who is said

to have ruled not only all Ireland, but a great part of Western Europe, and to

have wedded a Gaulish princess named Kesair. He had two sons, Laery and Covac.

The former inherited the kingdom, but Covac, consumed and sick with envy,

sought to slay him, and asked the advice of a Druid as to how this could be

managed, since Laery, justly suspicious, never would visit him without an armed

escort. The Druid bade him feign death, and have word sent to his brother that

he was on his bier ready for burial. This Covac did, and when Laery arrived and

bent over the supposed corpse Covac stabbed him to the heart, and slew also one

of his sons, Ailill,6 who attended him. Then Covac ascended the

throne, and straightway his illness left him.

Legends of Maon, Son of Ailill

He

did a brutal deed, however, upon a son of Ailill’s named Maon, about whom a

number of legends cluster. Maon, as a child, was brought into Covac’s presence,

and was there compelled, says Keating, to swallow a portion of his father’s and

grandfather’s hearts, and also a mouse with her young. From the disgust he

felt, the child lost his speech, and seeing him dumb, and therefore innocuous,

Covac let him go. The boy was then taken into Munster, to the kingdom of

Feramorc, of which Scoriath was king, and remained with him some time, but

afterwards went to Gaul, his great-grandmother Kesair’s country, where his

guards told the king that he was heir to the throne of Ireland, and he was

treated with great honour and grew up into a noble youth. But he left behind

him in the heart of Moriath, daughter of the King of Feramorc, a passion that

could not be stilled, and she resolved to bring him back to Ireland. She

accordingly equipped her father’s harper, Craftiny, with many rich gifts, and

wrote for him a love-lay, in which her passion for Maon was set forth, and to which

Craftiny composed an enchanting melody. Arrived in France, Craftiny made his

way to the king’s court, and found occasion to pour out his lay to Maon. So

deeply stirred was he by the beauty and passion of the song that his speech

returned to him and he broke out into praises of it, and was thenceforth dumb

no more. The King of Gaul then equipped him with an armed force and sent him to

Ireland to regain his kingdom. Learning that Covac was at a place near at hand

named Dinrigh, Maon and his body of Gauls made a sudden attack upon him and

slew him there and then, with all his nobles and guards. After the slaughter a

Druid of Covac’s company asked one of the Gauls who their leader was. “The

Mariner” (Loingseach), replied the Gaul, meaning the captain of the

fleet — i.e., Maon. “Can he speak?”

inquired the Druid, who had begun to suspect the truth. “He does speak” (Labraidh),

said the man; and henceforth the name “Labra the Mariner” clung to Maon son

of Ailill, nor was he known by any other. He then sought out Moriath, wedded

her, and reigned over Ireland ten years.

From

this invasion of the Gauls the name of the province of Leinster is traditionally

derived. They were armed with spears having broad blue-green iron heads called laighne

(pronounced “lyna”), and as they were allotted lands in Leinster and settled

there, the province was called in Irish Laighin (“Ly-in”) after them — the

Province of the Spearmen.7 Of

Labra the Mariner, after his accession, a curious tale is told. He was accustomed,

it is said, to have his hair cropped but once a year, and the man to do this

was chosen by lot, and was immediately afterwards put to death. The reason of

this was that, like King Midas in the similar Greek myth, he had long ears like

those of a horse, and he would not have this deformity known. Once it fell,

however, that the person chosen to crop his hair was the only son of a poor

widow, by whose tears and entreaties the king was prevailed upon to let him

live, on condition that he swore by the Wind and Sun to tell no man what he

might see. The oath was taken, and the young man returned to his mother. But

by-and-by the secret so preyed on his mind that he fell into a sore sickness,

and was near to death, when a wise Druid was called in to heal him. “It is the

secret that is killing him,” said the Druid, “and he will never be well till he

reveals it. Let him therefore go along the high-road till he come to a place

where four roads meet. Let him there turn to the right, and the first tree he

shall meet on the road, let him tell his secret to that, and he shall be rid of

it, and recover.” So the youth did; and the first tree was a willow. He laid

his lips close to the bark, whispered his secret to it, and went home,

light-hearted as of old. But it chanced that shortly after this the harper

Craftiny broke his harp and needed a new one, and as luck would have it the

first suitable tree he came to was the willow that had the king’s secret. He

cut it down, made his harp from it, and performed that night as usual in the

king’s hall; when, to the amazement of all, as soon as the harper touched the

strings the assembled guests heard them chime the words, “Two horse’s ears hath

Labra the Mariner.” The king then, seeing that the secret was out, plucked off

his hood and showed himself plainly; nor was any man put to death again on

account of this mystery. We have seen that the compelling power of Craftiny’s

music had formerly cured Labra’s dumbness. The sense of something magical in

music, as though supernatural powers spoke through it, is of constant

recurrence in Irish legend.  "The first tree was a willow" Legend-Cycle of Conary Mōr

We

now come to a cycle of legends centering on, or rather closing with, the

wonderful figure of the High King Conary Mōr — a cycle so charged with splendour,

mystery, and romance that to do it justice would require far more space than

can be given to it within the limits of this work.8 Etain in Fairyland

The

preliminary events of the cycle are transacted in the “Land of Youth,” the

mystic country of the People of Dana after their dispossession by the Children

of Miled. Midir the Proud son of the Dagda, a Danaan prince dwelling on Slieve

Callary, had a wife named Fuamnach. After a while he took to himself another

bride, Etain, whose beauty and grace were beyond compare, so that “as fair as

Etain” became a proverbial comparison for any beauty that exceeded all other

standards. Fuamnach therefore became jealous of her rival, and having by magic

art changed her into a butterfly, she raised a tempest that drove her forth

from the palace, and kept her for seven years buffeted hither and thither

throughout the length and breadth of Erin. At last, however, a chance gust of

wind blew her through a window of the fairy palace of Angus on the Boyne. The

immortals cannot be hidden from each other, and Angus knew what she was. Unable

to release her altogether from the spell of Fuamnach, he made a sunny bower for

her, and planted round it all manner of choice and honey-laden flowers, on

which she lived as long as she was with him, while in the secrecy of the night

he restored her to her own form and enjoyed her love. In time, however, her

refuge was discovered by Fuamnach; again the magic tempest descended upon her

and drove her forth; and this time a singular fate was hers. Blown into the

palace of an Ulster chieftain named Etar, she fell into the drinking-cup of

Etar’s wife just as the latter was about to drink. She was swallowed in the

draught, and in due time, having passed into the womb of Etar’s wife, she was

born as an apparently mortal child, and grew up to maidenhood knowing nothing

of her real nature and ancestry. Eochy and Etain

About

this time it happened that the High King of Ireland, Eochy,9 being

wifeless and urged by the nobles of his land to take a queen — “for without

thou do so,” they said, “we will not bring our wives to the Assembly at Tara” —

sent forth to inquire for a fair and noble maiden to share his throne. The

messengers report that Etain, daughter of Etar, is the fairest maiden in

Ireland, and the king journeys forth to visit her. A piece of description here

follows which is one of the most highly wrought and splendid in Celtic or

perhaps in any literature. Eochy finds Etain with her maidens by a spring of

water, whither she had gone forth to wash her hair: “A

clear comb of silver was held in her hand, the comb was adorned with gold; and

near her, as for washing, was a bason of silver whereon four birds had been

chased, and there were little bright gems of carbuncles on the rims of the

bason. A bright purple mantle waved round her; and beneath it was another

mantle ornamented with silver fringes: the outer mantle was clasped over her

bosom with a golden brooch. A tunic she wore with a long hood that might cover

her head attached to it; it was stiff and glossy with green silk beneath red

embroidery of gold, and was clasped over her breasts with marvellously wrought

clasps of silver and gold; so that men saw the bright gold and the green silk

flashing against the sun. On her head were two tresses of golden hair, and each

tress had been plaited into four strands; at the end of each strand was a

little ball of gold. And there was that maiden undoing her hair that she might

wash it, her two arms out through the armholes of her smock. Each of her two

arms was as white as the snow of a single night, and each of her cheeks was as

rosy as the foxglove. Even and small were the teeth in her head, and they shone

like pearls. Her eyes were as blue as a hyacinth, her lips delicate and crimson;

very high, soft and white were her shoulders. Tender, polished and white were

her wrists; her fingers long and of great whiteness; her nails were beautiful

and pink. White as snow, or the foam of a wave, was her neck; long was it,

slender, and as soft as silk. Smooth and white were her thighs; her knees were

round and firm and white; her ankles were as straight as the rule of a carpenter.

Her feet were slim and as white as the ocean’s foam; evenly set were her eyes;

her eyebrows were of a bluish black, such as you see upon the shell of a

beetle. Never a maid fairer than she, or more worthy of love, was till then

seen by the eyes of men; and it seemed to them that she must be one of those

that have come from the fairy mounds.”10 The

king wooed her and made her his wife, and brought her back to Tara. The Love-Story of Ailill

It

happened that the king had a brother named Ailill, who, on seeing Etain, was so

smitten with her beauty that he fell sick of the intensity of his passion and

wasted almost to death. While he was in this condition Eochy had to make a

royal progress through Ireland. He left his brother — the cause of whose malady

none suspected — in Etain’s care, bidding her do what she could for him, and,

if he died, to bury him with due ceremonies and erect an Ogham stone above his

grave.11 Etain goes to visit the brother; she inquires the cause of

his illness; he speaks to her in enigmas, but at last, moved beyond control by

her tenderness, he breaks out in an avowal of his passion. His description of

the yearning of hopeless love is a lyric of extraordinary intensity. “It is

closer than the skin,” he cries, “it is like a battle with a spectre, it

overwhelms like a flood, it is a weapon under the sea, it is a passion for an

echo.” By “a weapon under the sea” the poet means that love is like one of the secret

treasures of the fairy-folk in the kingdom of Mananan — as wonderful and as

unattainable. Etain

is now in some perplexity; but she decides, with a kind of naïve good-nature,

that although she is not in the least in love with Ailill, she cannot see a man

die of longing for her, and she promises to be his. Possibly we are to

understand here that she was prompted by the fairy nature, ignorant of good and

evil, and alive only to pleasure and to suffering. It must be said, however,

that in the Irish myths in general this, as we may call it, “fairy” view of

morality is the one generally prevalent both among Danaans and mortals — both

alike strike one as morally irresponsible.

Etain

now arranges a tryst with Ailill in a house outside of Tara — for she will not

do what she calls her “glorious crime” in the king’s palace. But Ailill on the

eve of the appointed day falls into a profound slumber and misses his

appointment. A being in his shape does, however, come to Etain, but merely to

speak coldly and sorrowfully of his malady, and departs again. When the two

meet once more the situation is altogether changed. In Ailill’s enchanted sleep

his unholy passion for the queen has passed entirely away. Etain, on the other

hand, becomes aware that behind the visible events there are mysteries which

she does not understand. Midir the Proud

The

explanation soon follows. The being who came to her in the shape of Ailill was

her Danaan husband, Midir the Proud. He now comes to woo her in his true shape,

beautiful and nobly apparelled, and entreats her to fly with him to the Land of

Youth, where she can be safe henceforward, since her persecutor, Fuamnach, is

dead. He it was who shed upon Ailill’s eyes the magic slumber. His description

of the fairyland to which he invites her is given in verses of great beauty: The Land of Youth

“O

fair-haired woman, will you come with me to the marvellous land, full of music,

where the hair is primrose-yellow and the body white as snow? There

none speaks of ‘mine’ or ‘thine’ — white are the teeth and black the brows;

eyes flash with many-coloured lights, and the hue of the foxglove is on every

cheek. Pleasant

to the eye are the plains of Erin, but they are a desert to the Great Plain. Heady

is the ale of Erin, but the ale of the Great Plain is headier. It is

one of the wonders of that land that youth does not change into age. Smooth

and sweet are the streams that flow through it; mead and wine abound of every

kind; there men are all fair, without blemish; there women conceive without

sin. We

see around us on every side, yet no man seeth us; the cloud of the sin of Adam

hides us from their observation. O

lady, if thou wilt come to my strong people, the purest of gold shall be on thy

head — thy meat shall be swine’s flesh unsalted,12 new milk and mead

shall thou drink with me there, O fair-haired woman." I

have given this remarkable lyric at length because, though Christian and ascetic

ideas are obviously discernible in it, it represents on the whole the pagan and

mythical conception of the Land of Youth, the country of the Dead. Etain,

however, is by no means ready to go away with a stranger and to desert the High

King for a man “without name or lineage.” Midir tells her who he is, and all

her own history of which, in her present incarnation, she knows nothing; and he

adds that it was one thousand and twelve years from Etain’s birth in the Land

of Youth till she was born a mortal child to the wife of Etar. Ultimately Etain

agrees to return with Midir to her ancient home, but only on condition that the

king will agree to their severance, and with this Midir has to be content for

the time. A Game of Chess

Shortly

afterwards he appears to King Eochy, as already related,13 on the

Hill of Tara. He tells the king that he has come to play a game of chess with

him, and produces a chessboard of silver with pieces of gold studded with

jewels. To be a skilful chess-player was a necessary accomplishment of kings

and nobles in Ireland, and Eochy enters into the game with zest. Midir allows

him to win game after game, and in payment for his losses he performs by magic

all kinds of tasks for Eochy, reclaiming land, clearing forests, and building

causeways across bogs — here we have a touch of the popular conception of the

Danaans as earth deities associated with agriculture and fertility. At last,

having excited Eochy’s cupidity and made him believe himself the better player,

he proposes a final game, the stakes to be at the pleasure of the victor after

the game is over. Eochy is now defeated.

“My

stake is forfeit to thee,” said Eochy. “Had

I wished it, it had been forfeit long ago,” said Midir. “What

is it that thou desirest me to grant?” said Eochy. “That

I may hold Etain in my arms and obtain a kiss from her,” said Midir. The

king was silent for a while; then he said: “One month from to-day thou shalt

come, and the thing thou desirest shall be granted thee.” Midir and Etain

Eochy’s

mind foreboded evil, and when the appointed day came he caused the palace of

Tara to be surrounded by a great host of armed men to keep Midir out. All was

in vain, however; as the king sat at the feast, while Etain handed round the

wine, Midir, more glorious than ever, suddenly stood in their midst. Holding his spears in his left

hand, he threw his right around Etain, and the couple rose lightly in the air

and disappeared through a roof-window in the palace. Angry and bewildered, the

king and his warriors rushed out of doors, but all they could see was two white

swans that circled in the air above the palace, and then departed in long, steady

flight towards the fairy mountain of Slievenamon. And thus Queen Etain rejoined

her kindred.  Midir and Etain War with Fairyland

Eochy,

however, would not accept defeat, and now ensues what I think is the earliest

recorded war with Fairyland since the first dispossession of the Danaans. After

searching Ireland for his wife in vain, he summoned to his aid the Druid Dalan.

Dalan tried for a year by every means in his power to find out where she was.

At last he made what seems to have been an operation of wizardry of special

strength — “he made three wands of yew, and upon the wands he wrote an ogham;

and by the keys of wisdom that he had, and by the ogham, it was revealed to him

that Etain was in the fairy mound of Bri-Leith, and that Midir had borne her

thither.” Eochy

then assembled his forces to storm and destroy the fairy mound in which was the

palace of Midir. It is said that he was nine years digging up one mound after

another, while Midir and his folk repaired the devastation as fast as it was

made. At last Midir, driven to the last stronghold, attempted a stratagem — he

offered to give up Etain, and sent her with fifty handmaids to the king, but

made them all so much alike that Eochy could not distinguish the true Etain

from her images. She herself, it is said, gave him a sign by which to know her.

The motive of the tale, including the choice of the mortal rather than the god,

reminds one of the beautiful Hindu legend of Damayanti and Nala. Eochy regained

his queen, who lived with him till his death, ten years afterwards, and bore

him one daughter, who was named Etain, like herself. The Tale of Conary Mōr

From

this Etain ultimately sprang the great king Conary Mōr, who shines in Irish

legend as the supreme type of royal splendour, power, and beneficence, and

whose overthrow and death were compassed by the Danaans in vengeance for the

devastation of their sacred dwellings by Eochy. The tale in which the death of

Conary is related is one of the most antique and barbaric in conception of all

Irish legends, but it has a magnificence of imagination which no other can

rival. To this great story the tale of Etain and Midir may be regarded as what

the Irish called a priomscel, “introductory tale,” showing the more

remote origin of the events related. The genealogy of Conary Mōr will help the

reader to understand the connexion of events.

The Law of the Geis

The

tale of Conary introduces us for the first time to the law or institution of

the geis, which plays henceforward a very important part in Irish

legend, the violation or observance of a geis being frequently the

turning-point in a tragic narrative. We must therefore delay a moment to

explain to the reader exactly what this peculiar institution was. Dineen’s

“Irish Dictionary” explains the word geis (pronounced “gaysh” — plural,

“gaysha”) as meaning “a bond, a spell, a prohibition, a taboo, a magical

injunction, the violation of which led to misfortune and death.”14

Every Irish chieftain or personage of note had certain geise peculiar to

himself which he must not transgress. These geise had sometimes

reference to a code of chivalry — thus Dermot of the Love-spot, when appealed

to by Grania to take her away from Finn, is under geise not to refuse

protection to a woman. Or they may be merely superstitious or fantastic — thus

Conary, as one of his geise, is forbidden to follow three red horsemen

on a road, nor must he kill birds (this is because, as we shall see, his totem

was a bird). It is a geis to the Ulster champion, Fergus mac Roy, that

he must not refuse an invitation to a feast; on this turns the Tragedy of the

Sons of Usnach. It is not at all clear who imposed these geise or how

any one found out what his personal geise were — all that was doubtless

an affair of the Druids. But they were regarded as sacred obligations, and the

worst misfortunes were to be apprehended from breaking them. Originally, no doubt,

they were regarded as a means of keeping oneself in proper relations with the

other world — the world of Faëry — and were akin to the well-known Polynesian

practice of the “tabu.” I prefer, however, to retain the Irish word as the only

fitting one for the Irish practice. The Cowherd’s Fosterling

We

now return to follow the fortunes of Etain’s great-grandson, Conary. Her

daughter, Etain Oig, as we have seen from the genealogical table, married

Cormac, King of Ulster. She bore her husband no children save one daughter

only. Embittered by her barrenness and his want of an heir, the king put away

Etain, and ordered her infant to be abandoned and thrown into a pit. “Then his

two thralls take her to a pit, and she smiles a laughing smile at them as they

were putting her into it.”15 After that they cannot leave her to

die, and they carry her to a cowherd of Eterskel, King of Tara, by whom she is

fostered and taught “till she became a good embroidress and there was not in

Ireland a king’s daughter dearer than she.” Hence the name she bore,

Messbuachalla (“Messboo´hala”), which means “the cowherd’s foster-child.” For

fear of her being discovered, the cowherds keep the maiden in a house of

wickerwork having only a roof-opening. But one of King Eterskel’s folk has the

curiosity to climb up and look in, and sees there the fairest maiden in

Ireland. He bears word to the king, who orders an opening to be made in the

wall and the maiden fetched forth, for the king was childless, and it had been

prophesied to him by his Druid that a woman of unknown race would bear him a son.

Then said the king: “This is the woman that has been prophesied to me.” Parentage and Birth of Conary

Before

her release, however, she is visited by a denizen from the Land of Youth. A

great bird comes down through her roof-window. On the floor of the hut his

bird-plumage falls from him and reveals

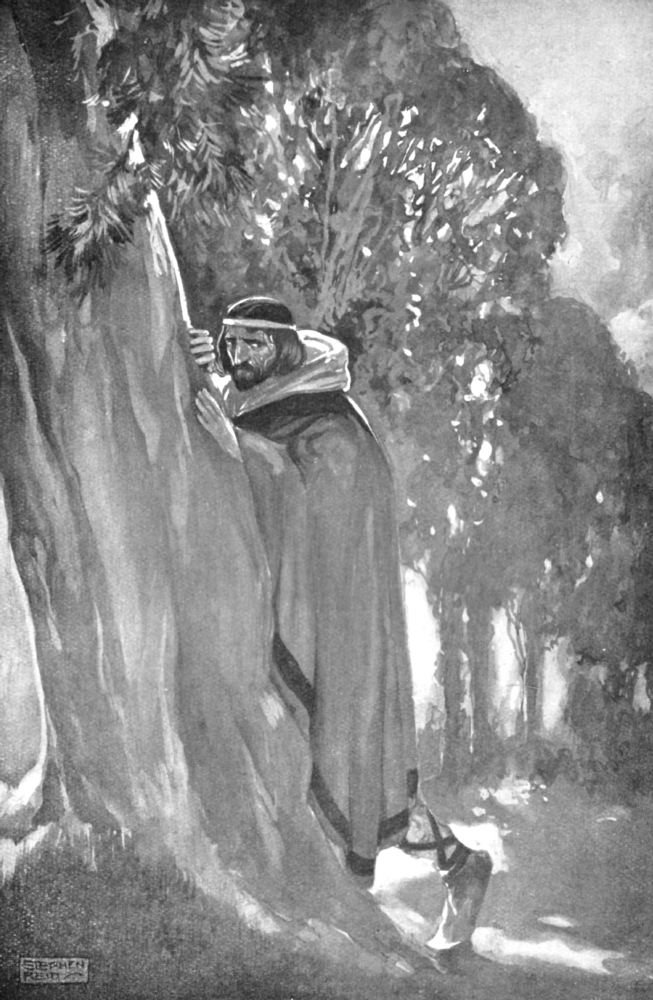

a glorious youth. Like Danaë, like Leda, like  "On the floor of the hut his bird-plumage falls from him." Ethlinn daughter of Balor, she gives

her love to the god. Ere they part he tells her that she will be taken to the

king, but that she will bear to her Danaan lover a son whose name shall be Conary,

and that it shall be forbidden to him to go a-hunting after birds. So

Conary was born, and grew up into a wise and noble youth, and he was fostered

with a lord named Desa, whose three great-grandsons grew up with him from

childhood. Their names were Ferlee and Fergar and Ferrogan; and Conary, it is

said, loved them well and taught them his wisdom. Conary the High King

Then

King Eterskel died, and a successor had to be appointed. In Ireland the eldest

son did not succeed to the throne or chieftaincy as a matter of right, but the

ablest and best of the family at the time was supposed to be selected by the

clan. In this tale we have a curious account of this selection by means of

divination. A “bull-feast” was held — i.e.,

a bull was slain, and the diviner would “eat his fill and drink its broth”;

then he went to bed, where a truth-compelling spell was chanted over him. Whoever

he saw in his dream would be king. So at Ægira, in Achæa, as Whitley Stokes

points out, the priestess of Earth drank the fresh blood of a bull before

descending into the cave to prophesy. The dreamer cried in his sleep that he

saw a naked man going towards Tara with a stone in his sling. The

bull-feast was held at Tara, but Conary was then with his three foster-brothers

playing a game on the Plains of Liffey. They separated, Conary going towards

Dublin, where he saw before him a flock of great birds, wonderful in colour and

beauty. He drove after them in his chariot, but the birds would go a spear-cast

in front and light, and fly on again, never letting him come up with them till

they reached the sea-shore. Then he lighted down from his chariot and took out

his sling to cast at them, whereupon they changed into armed men and turned on

him with spears and swords. One of them, however, protected him, and said: “I

am Nemglan, king of thy father’s birds; and thou hast been forbidden to cast at

birds, for here there is no one but is thy kin.” “Till to-day,” said Conary, “I

knew not this.” “Go

to Tara to-night,” said Nemglan; “the bull-feast is there, and through it thou

shalt be made king. A man stark naked, who shall go at the end of the night

along one of the roads to Tara, having a stone and a sling — ’tis he that shall

be king.” So

Conary stripped off his raiment and went naked through the night to Tara, where

all the roads were being watched by chiefs having changes of royal raiment with

them to clothe the man who should come according to the prophecy. When Conary

meets them they clothe him and bring him in, and he is proclaimed King of Erin. Conary’s Geise

A

long list of his geise is here given, which are said to have been declared

to him by Nemglan. “The bird-reign shall be noble,” said he, “and these shall

be thy geise: “Thou shalt not go right-handwise round Tara, nor

left-handwise round Bregia,16 Thou shalt not hunt the evil-beasts of Cerna, Thou shalt not go out every ninth night beyond Tara. Thou shalt not sleep in a house from which firelight shows

after sunset, or in which light can be seen from without. No three Reds shall go before thee to the house of Red. No rapine shall be wrought in thy reign. After sunset, no one woman alone or man alone shall enter

the house in which thou art. Thou shalt not interfere in a quarrel between two of thy

thralls.” Conary

then entered upon his reign, which was marked by the fair seasons and bounteous

harvests always associated in the Irish mind with the reign of a good king.

Foreign ships came to the ports. Oak-mast for the swine was up to the knees

every autumn; the rivers swarmed with fish. “No one slew another in Erin during

his reign, and to every one in Erin his fellow’s voice seemed as sweet as the

strings of lutes. From mid-spring to mid-autumn no wind disturbed a cow’s

tail.” Beginning of the Vengeance

Disturbance,

however, came from another source. Conary had put down all raiding and rapine,

and his three foster-brothers, who were born reavers, took it ill. They pursued

their evil ways in pride and wilfulness, and were at last captured red-handed.

Conary would not condemn them to death, as the people begged him to do, but

spared them for the sake of his kinship in fosterage. They were, however,

banished from Erin and bidden to go raiding overseas, if raid they must. On the

seas they met another exiled chief, Ingcel the One-Eyed, son of the King of

Britain, and joining forces with him they attacked the fortress in which

Ingcel’s father, mother, and brothers were guests at the time, and all were

destroyed in a single night. It was then the turn of Ingcel to ask their help

in raiding the land of Erin, and gathering a host of other outlawed men,

including the seven Manés, sons of Ailell and Maev of Connacht, besides Ferlee,

Fergar, and Ferrogan, they made a descent upon Ireland, taking land on the Dublin

coast near Howth. Meantime

Conary had been lured by the machinations of the Danaans into breaking one

after another of his geise. He settles a quarrel between two of his

serfs in Munster, and travelling back to Tara they see the country around it

lit with the glare of fires and wrapped in clouds of smoke. A host from the

North, they think, must be raiding the country, and to escape it Conary’s

company have to turn right-handwise round Tara and then left-handwise round the

Plain of Bregia. But the smoke and flames were an illusion made by the Fairy

Folk, who are now drawing the toils closer round the doomed king. On his way

past Bregia he chases “the evil beasts of Cerna” — whatever they were — “but he

saw it not till the chase was ended.” Da Derga’s Hostel and the Three Reds

Conary

had now to find a resting-place for the night, and he recollects that he is not

far from the Hostel of the Leinster lord, Da Derga, which gives its name to

this bardic tale.17 Conary had been generous to him when Da Derga

came visiting to Tara, and he determined to seek his hospitality for the night.

Da Derga dwelt in a vast hall with seven doors near to the present town of

Dublin, probably at Donnybrook, on the high-road to the south. As the cavalcade

are journeying thither an ominous incident occurs — Conary marks in front of

them on the road three horsemen clad all in red and riding on red horses. He

remembers his geis about the “three Reds,” and sends a messenger forward

to bid them fall behind. But however the messenger lashes his horse he fails to

get nearer than the length of a spear-cast to the three Red Riders. He shouts

to them to turn back and follow the king, but one of them, looking over his

shoulder, bids him ironically look out for “great news from a Hostel.” Again

and again the messenger is sent to them with promises of great reward if they

will fall behind instead of preceding Conary. At last one of them chants a mystic

and terrible strain. “Lo, my son, great the news. Weary are the steeds we ride — the steeds from the fairy mounds. Though we

are living, we are dead. Great are the signs: destruction of life; sating of

ravens; feeding of crows; strife of slaughter; wetting of sword-edge; shields

with broken bosses after sundown. Lo, my son!” Then they ride forward, and, alighting

from their red steeds, fasten them at the portal of Da Derga’s Hostel and sit

down inside. “Derga,” it may be explained, means “red.” Conary had therefore

been preceded by three red horsemen to the House of Red. “All my geise,”

he remarks forebodingly, “have seized me to-night.” Gathering of the Hosts

From

this point the story of Conary Mōr takes on a character of supernatural

vastness and mystery, the imagination of the bardic narrator dilating, as it

were, with the approach of the crisis. Night has fallen, and the pirate host of

Ingcel is encamped on the shores of Dublin Bay. They hear the noise of the

royal cavalcade, and a long-sighted messenger is sent out to discover what it

is. He brings back word of the glittering and multitudinous host which has

followed Conary to the Hostel. A crashing noise is heard — Ingcel asks of

Ferrogan what it may be — it is the giant warrior mac Cecht striking flint on

steel to kindle fire for the king’s feast. “God send that Conary be not there

to-night,” cry the sons of Desa; “woe that he should be under the hurt of his

foes.” But Ingcel reminds them of their compact — he had given them the

plundering of his own father and brethren; they cannot refuse to stand by him

in the attack he meditates on Conary in the Hostel. A glare of the fire lit by

mac Cecht is now perceived by the pirate host, shining through the wheels of

the chariots which are drawn up around the open doors of the Hostel. Another of

the geise of Conary has been broken.

Ingcel

and his host now proceed to build a great cairn of stones, each man contributing

one stone, so that there may be a memorial of the fight, and also a record of

the number slain when each survivor removes his stone again. The Morrigan

The

scene now shifts to the Hostel, where the king’s party has arrived and is

preparing for the night. A solitary woman comes to the door and seeks admission.

“As long as a weaver’s beam were each of her two shins, and they were as dark

as the back of a stag-beetle. A greyish, woolly mantle she wore. Her hair

reached to her knee. Her mouth was twisted to one side of her head.” It was the

Morrigan, the Danaan goddess of Death and Destruction. She leant against the

doorpost of the house and looked evilly on the king and his company. “Well, O

woman,” said Conary, “if thou art a witch, what seest thou for us?” “Truly I

see for thee,” she answered, “that neither fell nor flesh of thine shall escape

from the place into which thou hast come, save what birds will bear away in

their claws.” She asks admission. Conary declares that his geis forbids him to receive a solitary man or woman after sunset.

“If in sooth,” she says, “it has befallen the king not to have room in his

house for the meal and bed of a solitary woman, they will be gotten apart from

him from some one possessing generosity.” “Let her in, then,” says Conary,

“though it is a geis of mine.” Conary and his Retinue

A

lengthy and brilliant passage now follows describing how Ingcel goes to spy out

the state of affairs in the Hostel. Peeping through the chariot-wheels, he

takes note of all he sees, and describes to the sons of Desa the appearance and

equipment of each prince and mighty man in Conary’s retinue, while Ferrogan and

his brother declare who he is and what destruction he will work in the coming

fight. There is Cormac, son of Conor, King of Ulster, the fair and good; there

are three huge, black and black-robed warriors of the Picts; there is Conary’s

steward, with bristling hair, who settles every dispute — a needle would be

heard falling when he raises his voice to speak, and he bears a staff of office

the size of a mill-shaft; there is the warrior mac Cecht, who lies supine with

his knees drawn up — they resemble two bare hills, his eyes are like lakes, his

nose a mountain-peak, his sword shines like a river in the sun. Conary’s three

sons are there, golden-haired, silk-robed, beloved of all the household, with

“manners of ripe maidens, and hearts of brothers, and valour of bears.” When

Ferrogan hears of them he weeps and cannot proceed till hours of the night have

passed. Three Fomorian hostages of horrible aspect are there also; and Conall

of the Victories with his blood-red shield; and Duftach of Ulster with his

magic spear, which, when there is a premonition of battle, must be kept in a

brew of soporific herbs, or it will flame on its haft and fly forth raging for

massacre; and three giants from the Isle of Man with horses’ manes reaching to

their heels. A strange and unearthly touch is introduced by a description of

three naked and bleeding forms hanging by ropes from the roof — they are the

daughters of the Bav, another name for the Morrigan, or war-goddess, “three of

awful boding,” says the tale enigmatically, “those are the three that are slaughtered

at every time.” We are probably to regard them as visionary beings, portending

war and death, visible only to Ingcel. The hall with its separate chambers is

full of warriors, cup-bearers, musicians playing, and jugglers doing wonderful

feats; and Da Derga with his attendants dispensing food and drink. Conary

himself is described as a youth; “the ardour and energy of a king has he and

the counsel of a sage; the mantle I saw round him is even as the mist of

May-day — lovelier in each hue of it than the other.” His golden-hilted sword

lies beside him — a forearm’s length of it has escaped from the scabbard,

shining like a beam of light. “He is the mildest and gentlest and most perfect

king that has come into the world, even Conary son of Eterskel ... great is the

tenderness of the sleepy, simple man till he has chanced on a deed of valour.

But if his fury and his courage are awakened when the champions of Erin and

Alba are at him in the house, the Destruction will not be wrought so long as he

is therein ... sad were the quenching of that reign.” Champions at the House

Ingcel

and the sons of Desa then march to the attack and surround the Hostel: “Silence

a while!” says Conary, “what is this?” “Champions

at the house,” says Conall of the Victories.

“There

are warriors for them here,” answers Conary.

“They

will be needed to-night,” Conall rejoins.

One

of Desa’s sons rushes first into the Hostel. His head is struck off and cast

out of it again. Then the great struggle begins. The Hostel is set on fire, but

the fire is quenched with wine or any liquids that are in it. Conary and his

people sally forth — hundreds are slain, and the reavers, for the moment, are

routed. But Conary, who has done prodigies of fighting, is athirst and can do

no more till he gets water. The reavers by advice of their wizards have cut off

the river Dodder, which flowed through the Hostel, and all the liquids in the

house had been spilt on the fires. Death of Conary

The

king, who is perishing of thirst, asks mac Cecht to procure him a drink, and

mac Cecht turns to Conall and asks him whether he will get the drink for the

king or stay to protect him while mac Cecht does it. “Leave the defence of the

king to us,” says Conall, “and go thou to seek the drink, for of thee it is

demanded.” Mac Cecht then, taking Conary’s golden cup, rushes forth, bursting

through the surrounding host, and goes to seek for water. Then Conall, and

Cormac of Ulster, and the other champions, issue forth in turn, slaying

multitudes of the enemy; some return wounded and weary to the little band in

the Hostel, while others cut their way through the ring of foes. Conall,

Sencha, and Duftach stand by Conary till the end; but mac Cecht is long in

returning, Conary perishes of thirst, and the three heroes then fight their way

out and escape, “wounded, broken, and maimed.”

Meantime

mac Cecht has rushed over Ireland in frantic search for the water. But the

Fairy Folk, who are here manifestly elemental powers controlling the forces of

nature, have sealed all the sources against him. He tries the Well of Kesair in

Wicklow in vain; he goes to the great rivers, Shannon and Slayney, Bann and

Barrow — they all hide away at his approach; the lakes deny him also; at last

he finds a lake, Loch Gara in Roscommon, which failed to hide itself in time,

and thereat he fills his cup. In the morning he returned to the Hostel with the

precious and hard-won draught, but found the defenders all dead or fled, and

two of the reavers in the act of striking off the head of Conary. Mac Cecht

struck off the head of one of them, and hurled a huge pillar stone after the other,

who was escaping with Conary’s head. The reaver fell dead on the spot, and mac

Cecht, taking up his master’s head, poured the water into its mouth. Thereupon

the head spoke, and praised and thanked him for the deed. Mac Cecht’s Wound

A

woman then came by and saw mac Cecht lying exhausted and wounded on the field. “Come

hither, O woman,” says mac Cecht. “I

dare not go there,” says the woman, “for horror and fear of thee.” But

he persuades her to come, and says: “I know not whether it is a fly or gnat or

an ant that nips me in the wound.” The

woman looked and saw a hairy wolf buried as far as the two shoulders in the

wound. She seized it by the tail and dragged it forth, and it took “the full of

its jaws out of him.” “Truly,”

says the woman, “this is an ant of the Ancient Land.” And

mac Cecht took it by the throat and smote it on the forehead, so that it died. “Is thy Lord Alive?”

The

tale ends in a truly heroic strain. Conall of the Victories, as we have seen,

had cut his way out after the king’s death, and made his way to Teltin, where

he found his father, Amorgin, in the garth before his dūn. Conall’s shield-arm

had been wounded by thrice fifty spears, and he reached Teltin now with half a

shield, and his sword, and the fragments of his two spears. “Swift

are the wolves that have hunted thee, my son,” said his father. “’Tis

this that has wounded us, old hero, an evil conflict with warriors,” Conall

replied. “Is

thy lord alive?” asked Amorgin. “He

is not alive,” says Conall. “I

swear to God what the great tribes of Ulster swear: he is a coward who goes out

of a fight alive having left his lord with his foes in death.” “My

wounds are not white, old hero,” says Conall. He showed him his shield-arm,

whereon were thrice fifty spear-wounds. The sword-arm, which the shield had not

guarded, was mangled and maimed and wounded and pierced, save that the sinews

kept it to the body without separation. “That

arm fought to-night, my son,” says Amorgin.

“True

is that, old hero,” says Conall of the Victories. “Many are they to whom it

gave drinks of death to-night in front of the Hostel.” So ends the story of Etain, and of the

overthrow of Fairyland and the fairy vengeance wrought on the great-grandson of

Eochy the High King. 2 See p. 85. 3 “Omnia monumenta Scotorum ante Cimbaoth incerta erant.”

Tierna, who died in 1088, was Abbot of Clonmacnois, a great monastic and

educational centre in mediæval Ireland. 4 Compare the fine poem of a modern Celtic writer (Sir Samuel

Ferguson), “The Widow’s Cloak” — i.e.,

the British Empire in the days of Queen Victoria. 5 “Critical History of Ireland,” p. 180. 6 Pronounced “El´yill.” 7 The ending ster in three of the names of the Irish

provinces is of Norse origin, and is a relic of the Viking conquests in

Ireland. Connacht, where the Vikings did not penetrate, alone preserves its

Irish name unmodified. Ulster (in Irish Ulaidh) is supposed to derive its

name from Ollav Fōla, Munster (Mumhan) from King Eocho Mumho, tenth in

succession from Eremon, and Connacht was “the land of the children of Conn” —

he who was called Conn of the Hundred Battles, and who died A.D. 157. 8 The reader may, however, be referred to the tale of Etain

and Midir as given in full by A.H. Leahy (“Heroic Romances of Ireland”), and by

the writer in his “High Deeds of Finn,” and to the tale of Conary rendered by

Sir S. Ferguson (“Poems,” 1886), in what Dr. Whitley Stokes has described as

the noblest poem ever written by an Irishman. 9 Pronounced “Yeo´hee.” 10 I quote Mr. A.H. Leahy’s translation from a

fifteenth-century Egerton manuscript (“Heroic Romances of Ireland,” vol. i. p.

12). The story is, however, found in much more ancient authorities. 11 Ogham letters, which were composed of straight lines

arranged in a certain order about the axis formed by the edge of a squared

pillar-stone, were used for sepulchral inscription and writing generally before

the introduction of the Roman alphabet in Ireland. 12 The reference is to the magic swine of Mananan, which were

killed and eaten afresh every day, and whose meat preserved the eternal youth

of the People of Dana. 13 See p. 124. 14 The meaning quoted will be found in the Dictionary under

the alternative form geas 15 I quote from Whitley Stokes’ translation, Revue

Celtique, January 1901, and succeeding numbers. 16 Bregia was the great plain lying eastwards of Tara between

Boyne and Liffey 17 “The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel.” |