| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Myths & Legends: The Celtic Race Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

III: THE IRISH INVASION MYTHS The Celtic Cosmogony

Among

those secret doctrines about the “nature of things” which, as Cæsar tells us,

the Druids never would commit to writing, was there anything in the nature of a

cosmogony, any account of the origin of the world and of man? There surely was.

It would be strange indeed if, alone among the races of the world, the Celts

had no world-myth. The spectacle of the universe with all its vast and

mysterious phenomena in heaven and on earth has aroused, first the imagination,

afterwards the speculative reason, in every people which is capable of either.

The Celts had both in abundance, yet, except for that one phrase about the

“indestructibility” of the world handed down to us by Strabo, we know nothing

of their early imaginings or their reasonings on this subject. Ireland

possesses a copious legendary literature. All of this, no doubt, assumed its

present form in Christian times; yet so much essential paganism has been

allowed to remain in it that it would be strange if Christian influences had

led to the excision of everything in these ancient texts that pointed to a

non-Christian conception of the origin of things — if Christian editors and

transmitters had never given us even the least glimmer of the existence of such

a conception. Yet the fact is that they do not give it; there is nothing in the

most ancient legendary literature of the Irish Gaels, which is the oldest

Celtic literature in existence, corresponding to the Babylonian conquest of

Chaos, or the wild Norse myth of the making of Midgard out of the corpse of

Ymir, or the Egyptian creation of the universe out of the primeval Water by

Thoth, the Word of God, or even to the primitive folklore conceptions found in

almost every savage tribe. That the Druids had some doctrine on this subject it

is impossible to doubt. But, by resolutely confining it to the initiated and

forbidding all lay speculation on the subject, they seem to have completely

stifled the mythmaking instinct in regard to questions of cosmogony among the

people at large, and ensured that when their own order perished, their

teaching, whatever it was, should die with them. In

the early Irish accounts, therefore, of the beginnings of things, we find that

it is not with the World that the narrators make their start — it is simply

with their own country, with Ireland. It was the practice, indeed, to prefix to

these narratives of early invasions and colonisations the Scriptural account of

the making of the world and man, and this shows that something of the kind was

felt to be required; but what took the place of the Biblical narrative in

pre-Christian days we do not know, and, unfortunately, are now never likely to

know. The Cycles of Irish Legend

Irish

mythical and legendary literature, as we have it in the most ancient form, may

be said to fall into four main divisions, and to these we shall adhere in our

presentation of it in this volume. They are, in chronological order, the Mythological

Cycle, or Cycle of the Invasions, the Ultonian or Conorian Cycle, the Ossianic

or Fenian Cycle, and a multitude of miscellaneous tales and legends which it is

hard to fit into any historical framework.

The Mythological Cycle

The

Mythological Cycle comprises the following sections: 1. The coming of Partholan into

Ireland. 2. The coming of Nemed into Ireland.

3. The coming of the Firbolgs into

Ireland. 4. The invasion of the Tuatha De

Danann, or People

of the god Dana. 5. The invasion of the Milesians

(Sons of Miled) from

Spain, and their conquest of the People of Dana. With

the Milesians we begin to come into something resembling history — they represent,

in Irish legend, the Celtic race; and from them the ruling families of Ireland

are supposed to be descended. The People of Dana are evidently gods. The

pre-Danaan settlers or invaders are huge

phantom-like figures, which loom vaguely

through the mists of tradition, and have little definite characterisation. The

accounts which are given of them are many and conflicting, and out of these we

can only give here the more ancient narratives.

St. Finnen and the Pagan Chief The Coming of Partholan

The

Celts, as we have learned from Caesar, believed themselves to be descended from

the God of the Underworld, the God of the Dead. Partholan is said to have come

into Ireland from the West, where beyond the vast, unsailed Atlantic Ocean the

Irish Fairyland, the Land of the Living — i.e., the land of the Happy

Dead — was placed. His father’s name was

Sera (? the West). He came with his queen Dalny1 and a number of companions

of both sexes. Ireland — and this is an imaginative touch intended to suggest

extreme antiquity — was then a different country, physically, from what it is

now. There were then but three lakes in Ireland, nine rivers, and only one

plain. Others were added gradually during the reign of the Partholanians. One,

Lake Rury, was said to have burst out as a grave was being dug for Rury, son of

Partholan. The Fomorians

The

Partholanians, it is said, had to do battle with a strange race, called the

Fomorians, of whom we shall hear much in later sections of this book. They were

a huge, misshapen, violent and cruel people, representing, we may believe, the

powers of evil. One of these was surnamed Cenchos, which means The

Footless, and thus appears to be related to Vitra, the God of Evil in Vedantic

mythology, who had neither feet nor hands. With a host of these demons Partholan

fought for the lordship of Ireland, and drove them out to the northern seas,

whence they occasionally harried the country under its later rulers. The

end of the race of Partholan was that they were afflicted by pestilence, and

having gathered together on the Old Plain (Senmag) for convenience of burying

their dead, they all perished there; and Ireland once more lay empty for

reoccupation. The Legend of Tuan mac Carell

Who,

then, told the tale? This brings us to the mention of a very curious and

interesting legend — one of the numerous legendary narratives in which these

tales of the Mythical Period have come down to us. It is found in the so-called

“Book of the Dun Cow,” a manuscript of about the year A.D. 1100, and is

entitled “The Legend of Tuan mac Carell.”

St.

Finnen, an Irish abbot of the sixth century, is said to have gone to seek

hospitality from a chief named Tuan mac Carell, who dwelt not far from Finnen’s

monastery at Moville, Co. Donegal. Tuan refused him admittance. The saint sat

down on the doorstep of the chief and fasted for a whole Sunday,2

upon which the surly pagan warrior opened the door to him. Good relations were

established between them, and the saint returned to his monks. “Tuan

is an excellent man,” said he to them; “he will come to you and comfort you,

and tell you the old stories of Ireland.”3 This

humane interest in the old myths and legends of the country is, it may here be

observed, a feature as constant as it is pleasant in the literature of early

Irish Christianity. Tuan

came shortly afterwards to return the visit of the saint, and invited him and

his disciples to his fortress. They asked him of his name and lineage, and he

gave an astounding reply. “I am a man of Ulster,” he said. “My name is Tuan son

of Carell. But once I was called Tuan son of Starn, son of Sera, and my father,

Starn, was the brother of Partholan.” “Tell

us the history of Ireland,” then said Finnen, and Tuan began. Partholan, he

said, was the first of men to settle in Ireland. After the great pestilence

already narrated he alone survived, “for there is never a slaughter that one

man does not come out of it to tell the tale.” Tuan was alone in the land, and

he wandered about from one vacant fortress to another, from rock to rock,

seeking shelter from the wolves. For twenty-two years he lived thus alone,

dwelling in waste places, till at last he fell into extreme decrepitude and old

age. “Then

Nemed son of Agnoman took possession of Ireland. He [Agnoman] was my father’s

brother. I saw him from the cliffs, and kept avoiding him. I was long-haired,

clawed, decrepit, grey, naked, wretched, miserable. Then one evening I fell

asleep, and when I woke again on the morrow I was changed into a stag. I was young

again and glad of heart. Then I sang of the coming of Nemed and of his race,

and of my own transformation.... ‘I have put on a new form, a skin rough and

grey. Victory and joy are easy to me; a little while ago I was weak and

defenceless.’ ” Tuan is then king of all the deer of Ireland,

and so remained all the days of Nemed and his race. He

tells how the Nemedians sailed for Ireland in a fleet of thirty-two barks, in

each bark thirty persons. They went astray on the seas for a year and a half,

and most of them perished of hunger and thirst or of shipwreck. Nine only

escaped — Nemed himself, with four men and four women. These landed in Ireland,

and increased their numbers in the course of time till they were 8060 men and

women. Then all of them mysteriously died.

Again

old age and decrepitude fell upon Tuan, but another transformation awaited him.

“Once I was standing at the mouth of my cave — I still remember it — and I knew that my body changed into another

form. I was a wild boar. And I sang this song about it: “ ‘To-day I am a boar.... Time was

when I sat in the assembly that gave the judgments of Partholan. It was sung,

and all praised the melody. How pleasant was the strain of my brilliant

judgment! How pleasant to the comely young women! My chariot went along in majesty

and beauty. My voice was grave and sweet. My step was swift and firm in battle.

My face was full of charm. To-day, lo! I am changed into a black boar.’ “That is what I said. Yea, of a

surety I was a wild boar. Then I became young again, and I was glad. I was king

of the boar-herds in Ireland; and, faithful to any custom, I went the rounds of

my abode when I returned into the lands of Ulster, at the times old age and

wretchedness came upon me. For it was always there that my transformations took

place, and that is why I went back thither to await the renewal of my body.” Tuan

then goes on to tell how Semion son of Stariat settled in Ireland, from whom

descended the Firbolgs and two other tribes who persisted into historic times.

Again old age comes on, his strength fails him, and he undergoes another

transformation; he becomes “a great eagle of the sea,” and once more rejoices

in renewed youth and vigour. He then tells how the People of Dana came in,

“gods and false gods from whom every one knows the Irish men of learning are

sprung.” After these came the Sons of Miled, who conquered the People of Dana.

All this time Tuan kept the shape of the sea-eagle, till one day, finding

himself about to undergo another transformation, he fasted nine days; “then

sleep fell upon me, and I was changed into a salmon.” He rejoices in his new

life, escaping for many years the snares of the fishermen, till at last he is

captured by one of them and brought to the wife of Carell, chief of the

country. “The woman desired me and ate me by herself, whole, so that I passed

into her womb.” He is born again, and passes for Tuan son of Carell; but the

memory of his pre-existence and all his transformations and all the history of

Ireland that he witnessed since the days of Partholan still abides with him,

and he teaches all these things to the Christian monks, who carefully preserve them. This

wild tale, with its atmosphere of grey antiquity and of childlike wonder,

reminds us of the transformations of the Welsh Taliessin, who also became an

eagle, and points to that doctrine of the transmigration of the soul which, as

we have seen, haunted the imagination of the Celt. We

have now to add some details to the sketch of the successive colonisations of

Ireland outlined by Tuan mac Carell. The Nemedians

The

Nemedians, as we have seen, were akin to the Partholanians. Both of them came

from the mysterious regions of the dead, though later Irish accounts, which

endeavoured to reconcile this mythical matter with Christianity, invented for

them a descent from Scriptural patriarchs and an origin in earthly lands such

as Spain or Scythia. Both of them had to do constant battle with the Fomorians,

whom the later legends make out to be pirates from oversea, but who are

doubtless divinities representing the powers of darkness and evil. There is no

legend of the Fomorians coming into Ireland, nor were they regarded as at any

time a regular portion of the population. They were coeval with the world

itself. Nemed fought victoriously against them in four great battles, but

shortly afterwards died of a plague which carried off 2000 of his people with

him. The Fomorians were then enabled to establish their tyranny over Ireland.

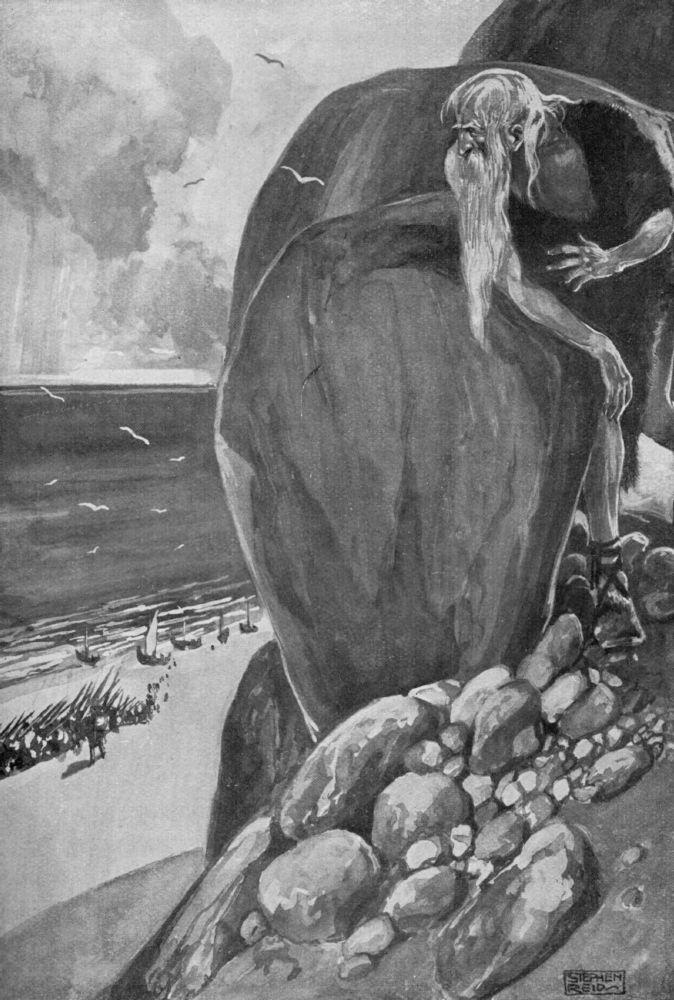

They had at this period two kings, Morc and Conann. The stronghold of the Formorian

power was on Tory Island, which uplifts

its wild cliffs and precipices in the Atlantic off

the coast of Donegal — a fit home for this race of mystery and horror. They

extracted a crushing tribute from the people of Ireland, two-thirds of all the

milk and two-thirds of the children of the land. At last the Nemedians rise in

revolt. Led by three chiefs, they land on Tory Island, capture Conann’s Tower,

and Conann himself falls by the hand of the Nemedian chief, Fergus. But Morc at

this moment comes into the battle with a fresh host, and utterly routs the Nemedians,

who are all slain but thirty:  “The men of Erin were all at the battle, After the Fomorians

came; All of them the sea

engulphed, Save only three times

ten.”

Poem by

Eochy O’Flann, circ. A.D. 960. The

thirty survivors leave Ireland in despair. According to the most ancient belief

they perished utterly, leaving no descendants, but later accounts, which

endeavour to make sober history out of all these myths, represent one family,

that of the chief Britan, as settling in Great Britain and giving their name to

that country, while two others returned to Ireland, after many wanderings, as

the Firbolgs and People of Dana. The Coming of the Firbolgs

Who

were the Firbolgs, and what did they represent in Irish legend? The name

appears to mean “Men of the Bags,” and a legend was in later times invented to

account for it. It was said that after settling in Greece they were oppressed

by the people of that country, who set them to carry earth from the fertile

valleys up to the rocky hills, so as to make arable ground of the latter. They

did their task by means of leathern bags; but at last, growing weary of the

oppression, they made boats or coracles out of their bags, and set sail in them

for Ireland. Nennius, however, says they came from Spain, for according to him

all the various races that inhabited Ireland came originally from Spain; and

“Spain” with him is a rationalistic rendering of the Celtic words designating

the Land of the Dead.4 They came in three groups, the Fir-Bolg, the

Fir-Domnan, and the Galioin, who are all generally designated as Firbolgs. They

play no great part in Irish mythical history, and a certain character of

servility and inferiority appears to attach to them throughout. One

of their kings, Eochy5 mac Erc, took in marriage Taltiu, or Telta, daughter

of the King of the “Great Plain” (the Land of the Dead). Telta had a palace at

the place now called after her, Telltown (properly Teltin). There she died, and

there, even in mediæval Ireland, a great annual assembly or fair was held in

her honour. The Coming of the People of Dana

We

now come to by far the most interesting and important of the mythical invaders

and colonisers of Ireland, the People of Dana. The name, Tuatha De Danann,

means literally “the folk of the god whose mother is Dana.” Dana also sometimes

bears another name, that of Brigit, a goddess held in much honour by pagan

Ireland, whose attributes are in a great measure transferred in legend to the

Christian St. Brigit of the sixth century. Her name is also found in Gaulish

inscriptions as “Brigindo,” and occurs in several British inscriptions as

“Brigantia.” She was the daughter of the supreme head of the People of Dana,

the god Dagda, “The Good.” She had three sons, who are said to have had in

common one only son, named Ecne — that is to say, “Knowledge,” or “Poetry.”6

Ecne, then, may be said to be the god whose mother was Dana, and the race to

whom she gave her name are the clearest representatives we have in Irish myths

of the powers of Light and Knowledge. It will be remembered that alone among

all these mythical races Tuan mac Carell gave to the People of Dana the name of

“gods.” Yet it is not as gods that they appear in the form in which Irish legends

about them have now come down to us. Christian influences reduced them to the

rank of fairies or identified them with the fallen angels. They were conquered

by the Milesians, who are conceived as an entirely human race, and who had all

sorts of relations of love and war with them until quite recent times. Yet even

in the later legends a certain splendour and exaltation appears to invest the

People of Dana, recalling the high estate from which they had been dethroned. The Popular and the Bardic

Conceptions

Nor

must it be overlooked that the popular conception of the Danaan deities was

probably at all times something different from the bardic and Druidic, or in

other words the scholarly, conception. The latter, as we shall see, represents

them as the presiding deities of science and poetry. This is not a popular

idea; it is the product of the Celtic, the Aryan imagination, inspired by a

strictly intellectual conception. The common people, who represented mainly the

Megalithic element in the population, appear to have conceived their deities as

earth-powers — dei terreni, as they are explicitly called in the

eighth-century “Book of Armagh”7 — presiding, not over science and

poetry, but rather agriculture, controlling the fecundity of the earth and

water, and dwelling in hills, rivers, and lakes. In the bardic literature the

Aryan idea is prominent; the other is to be found in innumerable folk-tales and

popular observances; but of course in each case a considerable amount of interpenetration

of the two conceptions is to be met with — no sharp dividing line was drawn

between them in ancient times, and none can be drawn now. The Treasures of the Danaans

Tuan

mac Carell says they came to Ireland “out of heaven.” This is embroidered in

later tradition into a narrative telling how they sprang from four great

cities, whose very names breathe of fairydom and romance — Falias, Gorias, Finias,

and Murias. Here they learned science and craftsmanship from great sages one of

whom was enthroned in each city, and from each they brought with them a magical

treasure. From Falias came the stone called the Lia Fail, or Stone of

Destiny, on which the High-Kings of Ireland stood when they were crowned, and

which was supposed to confirm the election of a rightful monarch by roaring

under him as he took his place on it. The actual stone which was so used at the

inauguration of a reign did from immemorial times exist at Tara, and was sent

thence to Scotland early in the sixth century for the crowning of Fergus the

Great, son of Erc, who begged his brother Murtagh mac Erc, King of Ireland, for

the loan of it. An ancient prophecy told that wherever this stone was, a king

of the Scotic (i.e., Irish-Milesian) race should reign. This is the famous

Stone of Scone, which never came back to Ireland, but was removed to England by

Edward I. in 1297, and is now the Coronation Stone in Westminster Abbey. Nor

has the old prophecy been falsified, since through the Stuarts and Fergus mac

Erc the descent of the British royal family can be traced from the historic

kings of Milesian Ireland. The

second treasure of the Danaans was the invincible sword of Lugh of the Long Arm,

of whom we shall hear later, and this sword came from the city of Gorias. From

Finias came a magic spear, and from Murias the Cauldron of the Dagda, a vessel

which had the property that it could feed a host of men without ever being

emptied. With

these possessions, according to the version given in the “Book of Invasions,”

the People of Dana came into Ireland. The Danaans and the Firbolgs

They

were wafted into the land in a magic cloud, making their first appearance in

Western Connacht. When the cloud cleared away, the Firbolgs discovered them in

a camp which they had already fortified at Moyrein. The

Firbolgs now sent out one of their warriors, named Sreng, to interview the

mysterious new-comers; and the People of Dana, on their side, sent a warrior

named Bres to represent them. The two ambassadors examined each other’s weapons

with great interest. The spears of the Danaans, we are told, were light and

sharp-pointed; those of the Firbolgs were heavy and blunt. To contrast the

power of science with that of brute force is here the evident intention of the

legend, and we are reminded of the Greek myth of the struggle of the Olympian

deities with the Titans. Bres

proposed to the Firbolg that the two races should divide Ireland equally

between them, and join to defend it against all comers for the future. They

then exchanged weapons and returned each to his own camp. The First Battle of Moytura

The

Firbolgs, however, were not impressed with the superiority of the Danaans, and

decided to refuse their offer. The battle was joined on the Plain of Moytura,8

in the south of Co. Mayo, near the spot now called Cong. The Firbolgs were led

by their king, mac Erc, and the Danaans by Nuada of the Silver Hand, who got

his name from an incident in this battle. His hand, it is said, was cut off in

the fight, and one of the skilful artificers who abounded in the ranks of the

Danaans made him a new one of silver. By their magical and healing arts the

Danaans gained the victory, and the Firbolg king was slain. But a reasonable

agreement followed: the Firbolgs were allotted the province of Connacht for their territory,

while the Danaans took the rest of Ireland. So late as the seventeenth century

the annalist Mac Firbis discovered that many of the inhabitants of Connacht

traced their descent to these same Firbolgs. Probably they were a veritable

historic race, and the conflict between them and the People of Dana may be a

piece of actual history invested with some of the features of a myth.  The Two Ambassadors The Expulsion of King Bres

Nuada

of the Silver Hand should now have been ruler of the Danaans, but his

mutilation forbade it, for no blemished man might be a king in Ireland. The

Danaans therefore chose Bres, who was the son of a Danaan woman named Eri, but

whose father was unknown, to reign over them instead. This was another Bres,

not the envoy who had treated with the Firbolgs and who was slain in the battle

of Moytura. Now Bres, although strong and beautiful to look on, had no gift of

kingship, for he not only allowed the enemy of Ireland, the Fomorians, to renew

their oppression and taxation in the land, but he himself taxed his subjects

heavily too; and was so niggardly that he gave no hospitality to chiefs and

nobles and harpers. Lack of generosity and hospitality was always reckoned the

worst of vices in an Irish prince. One day it is said that there came to his

court the poet Corpry, who found himself housed in a small, dark chamber

without fire or furniture, where, after long delay, he was served with three

dry cakes and no ale. In revenge he composed a satirical quatrain on his churlish

host: “Without food quickly served, Without a cow’s milk,

whereon a calf can grow, Without a dwelling

fit for a man under the gloomy night, Without means to

entertain a bardic company, — Let such be the

condition of Bres.” The

latter now betook himself in wrath and resentment to his mother Eri, and begged

her to give him counsel and to tell him of his lineage. Eri then declared to

him that his father was Elatha, a king of the Fomorians, who had come to her

secretly from over sea, and when he departed had given her a ring, bidding her

never bestow it on any man save him whose finger it would fit. She now brought

forth the ring, and it fitted the finger of Bres, who went down with her to the

strand where the Fomorian lover had landed, and they sailed together for his

father’s home. The Tyranny of the Fomorians

Elatha

recognised the ring, and gave his son an army wherewith to reconquer Ireland,

and also sent him to seek further aid from the greatest of the Fomorian kings,

Balor. Now Balor was surnamed “of the Evil Eye,” because the gaze of his one

eye could slay like a thunderbolt those on whom he looked in anger. He was now,

however, so old and feeble that the vast eyelid drooped over the death-dealing

eye, and had to be lifted up by his men with ropes and pulleys when the time

came to turn it on his foes. Nuada could make no more head against him than

Bres had done when king; and the country still groaned under the oppression of

the Fomorians and longed for a champion and redeemer. The Coming of Lugh

A new

figure now comes into the myth, no other than Lugh son of Kian, the Sun-god par

excellence of all Celtica, whose name we can still identify in many

historic sites on the Continent.10 To explain his appearance we must

desert for a moment the ancient manuscript authorities, which are here

incomplete, and have to be supplemented by a folk-tale which was fortunately

discovered and taken down orally so late as the nineteenth century by the great

Irish antiquary, O’Donovan.11 In this folk-tale the names of Balor

and his daughter Ethlinn (the latter in the form “Ethnea”) are preserved, as

well as those of some other mythical personages, but that of the father of Lugh

is faintly echoed in MacKineely; Lugh’s own name is forgotten, and the death of

Balor is given in a manner inconsistent with the ancient myth. In the story as

I give it here the antique names and mythical outline are preserved, but are

supplemented where required from the folk-tale, omitting from the latter those

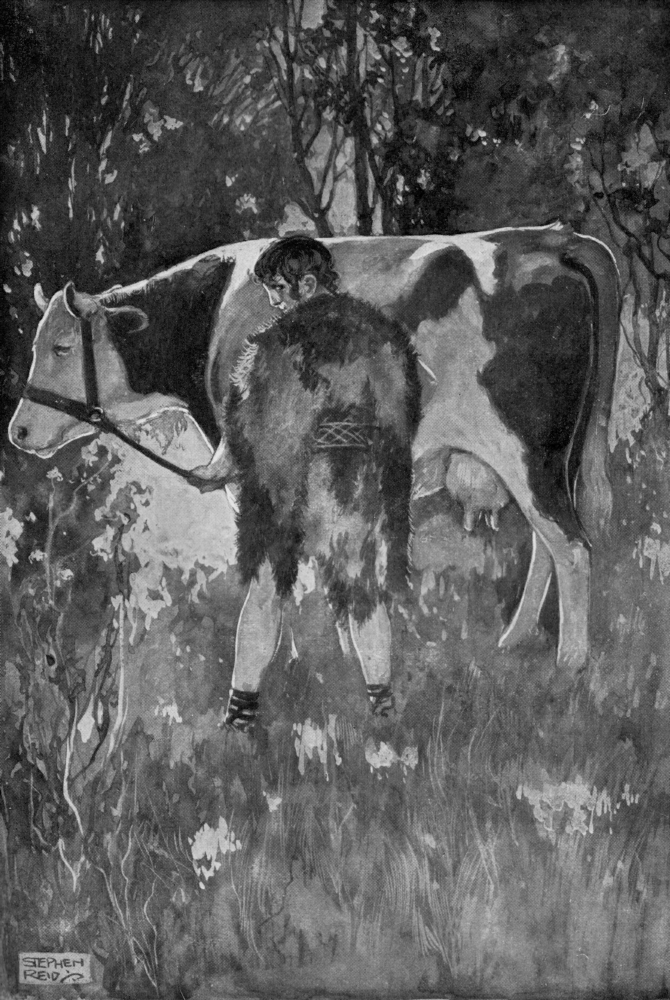

modern features which are not reconcilable with the myth.  "Sawan gave the cow's halter to the boy." The

story, then, goes that Balor, the Fomorian king, heard in a Druidic prophecy

that he would be slain by his grandson. His only child was an infant daughter

named Ethlinn. To avert the doom he, like Acrisios, father of Danae, in the

Greek myth, had her imprisoned in a high tower which he caused to be built on a

precipitous headland, the Tor Mōr, in Tory Island. He placed the girl in charge

of twelve matrons, who were strictly charged to prevent her from ever seeing

the face of man, or even learning that there were any beings of a different sex

from her own. In this seclusion Ethlinn grew up — as all sequestered princesses

do — into a maiden of surpassing beauty.

Now

it happened that there were on the mainland three brothers, namely, Kian,

Sawan, and Goban the Smith, the great armourer and artificer of Irish myth, who

corresponds to Wayland Smith in Germanic legend. Kian had a magical cow, whose

milk was so abundant that every one longed to possess her, and he had to keep

her strictly under protection. Balor

determined to possess himself of this cow. One day Kian and Sawan had come to

the forge to have some weapons made for them, bringing fine steel for that

purpose. Kian went into the forge, leaving Sawan in charge of the cow. Balor

now appeared on the scene, taking on himself the form of a little redheaded

boy, and told Sawan that he had overheard the brothers inside the forge

concocting a plan for using all the fine steel for their own swords, leaving

but common metal for that of Sawan. The latter, in a great rage, gave the cow’s

halter to the boy and rushed into the forge to put a stop to this nefarious

scheme. Balor immediately carried off the cow, and dragged her across the sea

to Tory Island. Kian

now determined to avenge himself on Balor, and to this end sought the advice of

a Druidess named Birōg. Dressing himself in woman’s garb, he was wafted by

magical spells across the sea, where Birōg, who accompanied him, represented to

Ethlinn’s guardians that they were two noble ladies cast upon the shore in

escaping from an abductor, and begged for shelter. They were admitted; Kian

found means to have access to the Princess Ethlinn while the matrons were laid

by Birōg under the spell of an enchanted slumber, and when they awoke Kian and

the Druidess had vanished as they came. But Ethlinn had given Kian her love,

and soon her guardians found that she was with child. Fearing Balor’s wrath,

the matrons persuaded her that the whole transaction was but a dream, and said

nothing about it; but in due time Ethlinn was delivered of three sons at a

birth. News

of this event came to Balor, and in anger and fear he commanded the three

infants to be drowned in a whirlpool off the Irish coast. The messenger who was

charged with this command rolled up the children in a sheet, but in carrying

them to the appointed place the pin of the sheet came loose, and one of the

children dropped out and fell into a little bay, called to this day Port na

Delig, or the Haven of the Pin. The other two were duly drowned, and the

servant reported his mission accomplished.

But

the child who had fallen into the bay was guarded by the Druidess, who wafted

it to the home of its father, Kian, and Kian gave it in fosterage to his

brother the smith, who taught the child his own trade and made it skilled in

every manner of craft and handiwork. This child was Lugh. When he was grown to

a youth the Danaans placed him in charge of Duach, “The Dark,” king of the

Great Plain (Fairyland, or the “Land of the Living,” which is also the Land of

the Dead), and here he dwelt till he reached manhood. Lugh

was, of course, the appointed redeemer of the Danaan people from their

servitude. His coming is narrated in a story which brings out the solar

attributes of universal power, and shows him, like Apollo, as the presiding

deity of all human knowledge and of all artistic and medicinal skill. He came,

it is told, to take service with Nuada of the Silver Hand, and when the

doorkeeper at the royal palace of Tara asked him what he could do, he answered

that he was a carpenter. “We

are in no need of a carpenter,” said the doorkeeper; “we have an excellent one

in Luchta son of Luchad.” “I am a smith too,” said Lugh. “We have a

master-smith,” said the doorkeeper, “already.” “Then I am a warrior,” said

Lugh. “We do not need one,” said the doorkeeper, “while we have Ogma.” Lugh

goes on to name all the occupations and arts he can think of — he is a poet, a

harper, a man of science, a physician, a spencer, and so forth, always

receiving the answer that a man of supreme accomplishment in that art is

already installed at the court of Nuada. “Then ask the King,” said Lugh, “if he

has in his service any one man who is accomplished in every one of these arts,

and if he have, I shall stay here no longer, nor seek to enter his palace.”

Upon this Lugh is received, and the surname Ildánach is conferred upon him,

meaning “The All-Craftsman,” Prince of all the Sciences; while another name

that he commonly bore was Lugh Lamfada, or Lugh of the Long Arm. We are

reminded here, as de Jubainville points out, of the Gaulish god whom Caesar

identifies with Mercury, “inventor of all the arts,” and to whom the Gauls put

up many statues. The Irish myth supplements this information and tells us the Celtic

name of this deity. When

Lugh came from the Land of the Living he brought with him many magical gifts.

There was the Boat of Mananan, son of Lir the Sea God, which knew a man’s

thoughts and would travel whithersoever he would, and the Horse of Mananan,

that could go alike over land and sea, and a terrible sword named Fragarach

(“The Answerer”), that could cut through any mail. So equipped, he appeared one

day before an assembly of the Danaan chiefs who were met to pay their tribute

to the envoys of the Fomorian oppressors; and when the Danaans saw him, they

felt, it is said, as if they beheld the rising of the sun on a dry summer’s

day. Instead of paying the tribute, they, under Lugh’s leadership, attacked the

Fomorians, all of whom were slain but nine men, and these were sent back to

tell Balor that the Danaans defied him and would pay no tribute henceforward. Balor

then made him ready for battle, and bade his captains, when they had subdued

the Danaans, make fast the island by cables to their ships and tow it far

northward to the Fomorian regions of ice and gloom, where it would trouble them

no longer. The Quest of the Sons of Turenn

Lugh,

on his side, also prepared for the final combat; but to ensure victory certain

magical instruments were still needed for him, and these had now to be

obtained. The story of the quest of these objects, which incidentally tells us

also of the end of Lugh’s father, Kian, is one of the most valuable and curious

in Irish legend, and formed one of a triad of mythical tales which were

reckoned as the flower of Irish romance.12 Kian,

the story goes, was sent northward by Lugh to summon the fighting men of the

Danaans in Ulster to the hosting against the Fomorians. On his way, as he

crosses the Plain of Murthemney, near Dundalk, he meets with three brothers,

Brian, Iuchar, and Iucharba, sons of Turenn, between whose house and that of

Kian there was a blood-feud. He seeks to avoid them by changing into the form

of a pig and joining a herd which is rooting in the plain, but the brothers

detect him and Brian wounds him with a cast from a spear. Kian, knowing that

his end is come, begs to be allowed to change back into human form before he is

slain. “I had liefer kill a man than a pig,” says Brian, who takes throughout

the leading part in all the brothers’ adventures. Kian then stands before them

as a man, with the blood from Brian’s spear trickling from his breast. “I have

outwitted ye,” he cries, “for if ye had slain a pig ye would have paid but the

eric [blood-fine] of a pig, but now ye shall pay the eric of a man; never was greater

eric than that which ye shall pay; and the weapons ye slay me with shall tell

the tale to the avenger of blood.” “Then

you shall be slain with no weapons at all,” says Brian, and he and the brothers

stone him to death and bury him in the ground as deep as the height of a man. But

when Lugh shortly afterwards passes that way the stones on the plain cry out

and tell him of his father’s murder at the hands of the sons of Turenn. He

uncovers the body, and, vowing vengeance, returns to Tara. Here he accuses the

sons of Turenn before the High King, and is permitted to have them executed, or

to name the eric he will accept in remission of that sentence. Lugh chooses to

have the eric, and he names it as follows, concealing things of vast price, and

involving unheard-of toils, under the names of common objects: Three apples,

the skin of a pig, a spear, a chariot with two horses, seven swine, a hound, a

cooking-spit, and, finally, to give three shouts on a hill. The brothers bind

themselves to pay the fine, and Lugh then declares the meaning of it. The three

apples are those which grow in the Garden of the Sun; the pig-skin is a magical

skin which heals every wound and sickness if it can be laid on the sufferer,

and it is a possession of the King of Greece; the spear is a magical weapon

owned by the King of Persia (these names, of course, are mere fanciful

appellations for places in the mysterious world of Faëry); the seven swine

belong to King Asal of the Golden Pillars, and may be killed and eaten every

night and yet be found whole next day; the spit belongs to the sea-nymphs of

the sunken Island of Finchory; and the three shouts are to be given on the hill

of a fierce warrior, Mochaen, who, with his sons, are under vows to prevent any

man from raising his voice on that hill. To fulfil any one of these enterprises

would be an all but impossible task, and the brothers must accomplish them all

before they can clear themselves of the guilt and penalty of Kian’s death.  The

story then goes on to tell how with infinite daring and resource the sons of

Turenn accomplish one by one all their tasks, but when all are done save the

capture of the cooking-spit and the three shouts on the Hill of Mochaen, Lugh,

by magical arts, causes forgetfulness to fall upon them, and they return to

Ireland with their treasures. These, especially the spear and the pig-skin, are

just what Lugh needs to help him against the Fomorians; but his vengeance is

not complete, and after receiving the treasures he reminds the brothers of what

is yet to be won. They, in deep dejection, now begin to understand how they are

played with, and go forth sadly to win, if they can, the rest of the eric.

After long wandering they discover that the Island of Finchory is not above,

but under the sea. Brian in a magical “water-dress” goes down to it, sees the

thrice fifty nymphs in their palace, and seizes the golden spit from their

hearth. The ordeal of the Hill of Mochaen is the last to be attempted. After a desperate

combat which ends in the slaying of Mochaen and his sons, the brothers,

mortally wounded, uplift their voices in three faint cries, and so the eric is

fulfilled. The life is still in them, however, when they return to Ireland, and

their aged father, Turenn, implores Lugh for the loan of the magic pig-skin to

heal them; but the implacable Lugh refuses, and the brothers and their father

die together. So ends the tale. The Second Battle of Moytura

The

Second Battle of Moytura took place on a plain in the north of Co. Sligo, which

is remarkable for the number of sepulchral monuments still scattered over it.

The first battle, of course, was that which the Danaans had waged with the

Firbolgs, and the Moytura there referred to was much further south, in Co.

Mayo. The battle with the Fomorians is related with an astounding wealth of

marvellous incident. The craftsmen of the Danaans, Goban the smith, Credné the artificer

(or goldsmith), and Luchta the carpenter, keep repairing the broken weapons of

the Danaans with magical speed — three blows of Goban’s hammer make a spear or

sword, Luchta flings a handle at it and it sticks on at once, and Credné jerks

the rivets at it with his tongs as fast as he makes them and they fly into

their places. The wounded are healed by the magical pig-skin. The plain

resounds with the clamour of battle:

“Fearful indeed was the thunder which rolled over the battlefield; the

shouts of the warriors, the breaking of the shields, the flashing and clashing

of the swords, of the straight, ivory-hilted swords, the music and harmony of

the ‘belly-darts’ and the sighing and winging of the spears and lances.”13 The Death of Balor

The

Fomorians bring on their champion, Balor, before the glance of whose terrible

eye Nuada of the Silver Hand and others of the Danaans go down. But Lugh,

seizing an opportunity when the eyelid drooped through weariness, approached

close to Balor, and as it began to lift once more he hurled into the eye a

great stone which sank into the brain, and Balor lay dead, as the prophecy had

foretold, at the hand of his grandson. The Fomorians were then totally routed,

and it is not recorded that they ever again gained any authority or committed

any extensive depredations in Ireland. Lugh, the Ildánach, was then enthroned

in place of Nuada, and the myth of the victory of the solar hero over the

powers of darkness and brute force is complete.

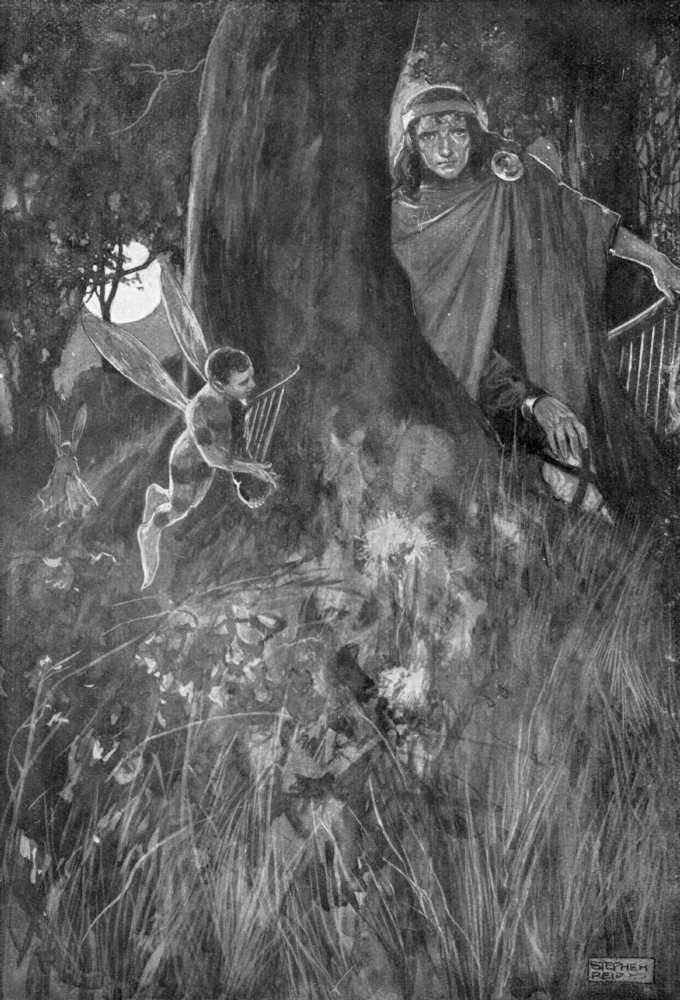

The Harp of the Dagda

A

curious little incident bearing on the power which the Danaans could exercise

by the spell of music may here be inserted. The flying Fomorians, it is told,

had made prisoner the harper of the Dagda and carried him off with them. Lugh,

the Dagda, and the warrior Ogma followed them, and came unknown into the

banqueting-hall of the Fomorian camp. There they saw the harp hanging on the

wall. The Dagda called to it, and immediately it flew into his hands, killing

nine men of the Fomorians on its way. The Dagda’s invocation of the harp is

very singular, and not a little puzzling:

“Come, apple-sweet murmurer,” he cries, “come, four-angled frame of

harmony, come, Summer, come, Winter, from the mouths of harps and bags and

pipes.”14  The

allusion to summer and winter suggests the practice in Indian music of allotting

certain musical modes to the different seasons of the year (and even to

different times of day), and also an Egyptian legend referred to in Burney’s

“History of Music,” where the three strings of the lyre were supposed to answer

respectively to the three seasons, spring, summer, and winter.15 When

the Dagda got possession of the harp, the tale goes on, he played on it the

“three noble strains” which every great master of the harp should command,

namely, the Strain of Lament, which caused the hearers to weep, the Strain of

Laughter, which made them merry, and the Strain of Slumber, or Lullaby, which

plunged them all in a profound sleep. And under cover of that sleep the Danaan

champion stole out and escaped. It may be observed that throughout the whole of

the legendary literature of Ireland skill in music, the art whose influence

most resembles that of a mysterious spell or gift of Faëry, is the prerogative

of the People of Dana and their descendants. Thus in the “Colloquy of the

Ancients,” a collection of tales made about the thirteenth or fourteenth

century, St. Patrick is introduced to a minstrel, Cascorach, “a handsome,

curly-headed, dark-browed youth,” who plays so sweet a strain that the saint

and his retinue all fall asleep. Cascorach, we are told, was son of a minstrel

of the Danaan folk. St. Patrick’s scribe, Brogan, remarks, “A good cast of

thine art is that thou gavest us.” “Good indeed it were,” said Patrick, “but

for a twang of the fairy spell that infests it; barring which nothing could

more nearly resemble heaven’s harmony.”16 Some of the most beautiful

of the antique Irish folk-melodies, — e.g., the Coulin — are traditionally

supposed to have been overheard by mortal harpers at the revels of the Fairy

Folk. Names and Characteristics of the

Danaan Deities

I may

conclude this narrative of the Danaan conquest with some account of the

principal Danaan gods and their attributes, which will be useful to readers of

the subsequent pages. The best with which I am acquainted is to be found in Mr.

Standish O’Grady’s “Critical History of Ireland.”17 This work is no

less remarkable for its critical insight — it was published in 1881, when

scientific study of the Celtic mythology was little heard of — than for the

true bardic imagination, kindred to that of the ancient myth-makers themselves,

which recreates the dead forms of the past and dilates them with the breath of

life. The broad outlines in which Mr. O’Grady has laid down the typical

characteristics of the chief personages in the Danaan cycle hardly need any

correction at this day, and have been of much use to me in the following

summary of the subject. The Dagda

The

Dagda Mōr was the father and chief of the People of Dana. A certain conception

of vastness attaches to him and to his doings. In the Second Battle of Moytura

his blows sweep down whole ranks of the enemy, and his spear, when he trails it

on the march, draws a furrow in the ground like the fosse which marks the

mearing of a province. An element of grotesque humour is present in some of the

records about this deity. When the Fomorians give him food on his visit to

their camp, the porridge and milk are poured into a great pit in the ground,

and he eats it with a spoon big enough, it was said, for a man and a woman to

lie together in it. With this spoon he scrapes the pit, when the porridge is

done, and shovels earth and gravel unconcernedly down his throat. We have

already seen that, like all the Danaans, he is a master of music, as well as of

other magical endowments, and owns a harp which comes flying through the air at

his call. “The tendency to attribute life to inanimate things is apparent in the

Homeric literature, but exercises a very great influence in the mythology of

this country. The living, fiery spear of Lugh; the magic ship of Mananan; the

sword of Conary Mōr, which sang; Cuchulain’s sword, which spoke; the Lia Fail,

Stone of Destiny, which roared for joy beneath the feet of rightful kings; the

waves of the ocean, roaring with rage and sorrow when such kings are in

jeopardy; the waters of the Avon Dia, holding back for fear at the mighty duel

between Cuchulain and Ferdia, are but a few out of many examples.”18

A legend of later times tells how once, at the death of a great scholar, all

the books in Ireland fell from their shelves upon the floor. Angus Ōg

Angus

Ōg (Angus the Young), son of the Dagda, by Boanna (the river Boyne), was the

Irish god of love. His palace was supposed to be at New Grange, on the Boyne.

Four bright birds that ever hovered about his head were supposed to be his

kisses taking shape in this lovely form, and at their singing love came

springing up in the hearts of youths and maidens. Once he fell sick of love for

a maiden whom he had seen in a dream. He told the cause of his sickness to his

mother Boanna, who searched all Ireland for the girl, but could not find her.

Then the Dagda was called in, but he too was at a loss, till he called to his

aid Bōv the Red, king of the Danaans of Munster — the same whom we have met

with in the tale of the Children of Lir, and who was skilled in all mysteries

and enchantments. Bōv undertook the search, and after a year had gone by

declared that he had found the visionary maiden at a lake called the Lake of

the Dragon’s Mouth. Angus

goes to Bōv, and, after being entertained by him three days, is brought to the

lake shore, where he sees thrice fifty maidens walking in couples, each couple

linked by a chain of gold, but one of them is taller than the rest by a head

and shoulders. “That is she!” cries Angus. “Tell us by what name she is known.”

Bōv answers that her name is Caer, daughter of Ethal Anubal, a prince of the

Danaans of Connacht. Angus laments that he is not strong enough to carry her

off from her companions, but, on Bōv’s advice, betakes himself to Ailell and

Maev, the mortal King and Queen of Connacht, for assistance. The Dagda and

Angus then both repair to the palace of Ailell, who feasts them for a week, and

then asks the cause of their coming. When it is declared he answers, “We have

no authority over Ethal Anubal.” They send a message to him, however, asking

for the hand of Caer for Angus, but Ethal refuses to give her up. In the end he

is besieged by the combined forces of Ailell and the Dagda, and taken prisoner.

When Caer is again demanded of him he declares that he cannot comply, “for she

is more powerful than I.” He explains that she lives alternately in the form of

a maiden and of a swan year and year about, “and on the first of November

next,” he says, “you will see her with a hundred and fifty other swans at the

Lake of the Dragon’s Mouth.” Angus

goes there at the appointed time, and cries to her, “Oh, come and speak to me!”

“Who calls me?” asks Caer. Angus explains who he is, and then finds himself

transformed into a swan. This is an indication of consent, and he plunges in to

join his love in the lake. After that they fly together to the palace on the

Boyne, uttering as they go a music so divine that all hearers are lulled to

sleep for three days and nights. Angus

is the special deity and friend of beautiful youths and maidens. Dermot of the

Love-spot, a follower of Finn mac Cumhal, and lover of Grania, of whom we shall

hear later, was bred up with Angus in the palace on the Boyne. He was the

typical lover of Irish legend. When he was slain by the wild boar of Ben

Bulben, Angus revives him and carries him off to share his immortality in his

fairy palace. Len of Killarney

Of

Bōv the Red, brother of the Dagda, we have already heard. He had, it is said, a

goldsmith named Len, who “gave their ancient name to the Lakes of Killarney,

once known as Locha Lein, the Lakes of Len of the Many Hammers. Here by the

lake he wrought, surrounded by rainbows and showers of fiery dew.”19 Lugh

Lugh

has already been described.20 He has more distinctly solar attributes

than any other Celtic deity; and, as we know, his worship was spread widely over

Continental Celtica. In the tale of the Quest of the Sons of Turenn we are told

that Lugh approached the Fomorians from the west. Then Bres, son of Balor,

arose and said: “I wonder that the sun is rising in the west to-day, and in the

east every other day.” “Would it were so,” said his Druids. “Why, what else but

the sun is it?” said Bres. “It is the radiance of the face of Lugh of the Long

Arm,” they replied. Lugh

was the father, by the Milesian maiden Dectera, of Cuchulain, the most heroic

figure in Irish legend, in whose story there is evidently a strong element of

the solar myth.21 Midir the Proud

Midir

the Proud is a son of the Dagda. His fairy palace is at Bri Leith, or

Slieve Callary, in Co. Longford. He frequently appears in legends dealing

partly with human, partly with Danaan personages, and is always represented as

a type of splendour in his apparel and in personal beauty. When he appears to

King Eochy on the Hill of Tara he is thus described:22 “It

chanced that Eochaid Airemm, the King of Tara, arose upon a certain fair day in

the time of summer; and he ascended the high ground of Tara23 to

behold the plain of Breg; beautiful was the colour of that plain, and there was

upon it excellent blossom glowing with all hues that are known. And as the

aforesaid Eochy looked about and around him, he saw a young strange warrior

upon the high ground at his side. The tunic that the warrior wore was purple in

colour, his hair was of a golden yellow, and of such length that it reached to

the edge of his shoulders. The eyes of the young warrior were lustrous and

grey; in the one hand he held a fine pointed spear, in the other a shield with

a white central boss, and with gems of gold upon it. And Eochaid held his

peace, for he knew that none such had

been in Tara on the night before, and

the gate that led into the Liss had not at that time been thrown open.”24 Lir and Mananan

Lir,

as Mr. O’Grady remarks, “appears in two distinct forms. In the first he is a

vast, impersonal presence commensurate with the sea; in fact, the Greek

Oceanus. In the second, he is a separate person dwelling invisibly on Slieve

Fuad,” in Co. Armagh. We hear little of him in Irish legend, where the

attributes of the sea-god are mostly conferred on his son, Mananan. This

deity is one of the most popular in Irish mythology. He was lord of the sea,

beyond or under which the Land of Youth or Islands of the Dead were supposed to

lie; he therefore was the guide of man to this country. He was master of tricks

and illusions, and owned all kinds of magical possessions — the boat named

Ocean-sweeper, which obeyed the thought of those who sailed in it and went

without oar or sail, the steed Aonbarr, which could travel alike on sea or

land, and the sword named The Answerer, which no armour could resist.

White-crested waves were called the Horses of Mananan, and it was forbidden (tabu)

for the solar hero, Cuchulain, to perceive them — this indicated the daily

death of the sun at his setting in the western waves. Mananan wore a great

cloak which was capable of taking on every kind of colour, like the widespread

field of the sea as looked on from a height; and as the protector of the island

of Erin it was said that when any hostile force invaded it they heard his

thunderous tramp and the flapping of his mighty cloak as he marched angrily

round and round their camp at night. The Isle of Man, seen dimly from the Irish

coast, was supposed to be the throne of Mananan, and to take its name from this

deity. The Goddess Dana

The

greatest of the Danaan goddesses was Dana, “mother of the Irish gods,” as she

is called in an early text. She was daughter of the Dagda, and, like him,

associated with ideas of fertility and blessing. According to d’Arbois de

Jubainville, she was identical with the goddess Brigit, who was so widely

worshipped in Celtica. Brian, Iuchar, and Iucharba are said to have been her

sons — these really represent but one person, in the usual Irish fashion of

conceiving the divine power in triads. The name of Brian, who takes the lead in

all the exploits of the brethren,25 is a derivation from a more

ancient form, Brenos, and under this form was the god to whom the Celts

attributed their victories at the Allia and at Delphi, mistaken by Roman and

Greek chroniclers for an earthly leader.

The Morrigan

There

was also an extraordinary goddess named the Morrigan,26 who appears

to embody all that is perverse and horrible among supernatural powers. She

delighted in setting men at war, and fought among them herself, changing into

many frightful shapes and often hovering above fighting armies in the aspect of

a crow. She met Cuchulain once and proffered him her love in the guise of a

human maid. He refused it, and she persecuted him thenceforward for the most of

his life. Warring with him once in the middle of the stream, she turned herself

into a water-serpent, and then into a mass of water-weeds, seeking to entangle and

drown him. But he conquered and wounded her, and she afterwards became his

friend. Before his last battle she passed through Emain Macha at night, and

broke the pole of his chariot as a warning.

Cleena’s Wave

One

of the most notable landmarks of Ireland was the Tonn Cliodhna, or “Wave

of Cleena,” on the seashore at Glandore Bay, in Co. Cork. The story about

Cleena exists in several versions, which do not agree with each other except in

so far as she seems to have been a Danaan maiden once living in Mananan’s

country, the Land of Youth beyond the sea. Escaping thence with a mortal lover,

as one of the versions tells, she landed on the southern coast of Ireland, and

her lover, Keevan of the Curling Locks, went off to hunt in the woods. Cleena,

who remained on the beach, was lulled to sleep by fairy music played by a

minstrel of Mananan, when a great wave of the sea swept up and carried her back

to Fairyland, leaving her lover desolate. Hence the place was called the Strand

of Cleena’s Wave. The Goddess Ainé

Another

topical goddess was Ainé, the patroness of Munster, who is still venerated by

the people of that county. She was the daughter of the Danaan Owel, a

foster-son of Mananan and a Druid. She is in some sort a love-goddess,

continually inspiring mortals with passion. She was ravished, it was said, by

Ailill Olum, King of Munster, who was slain in consequence by her magic arts,

and the story is repeated in far later times about another mortal lover, who

was not, however, slain, a Fitzgerald, to whom she bore the famous wizard Earl.27

Many of the aristocratic families of Munster claimed descent from this union.

Her name still clings to the “Hill of Ainé” (Knockainey), near Loch Gur, in Munster.

All the Danaan deities in the popular imagination were earth-gods, dei

terreni, associated with ideas of fertility and increase. Ainé is not heard

much of in the bardic literature, but she is very prominent in the folk-lore of

the neighbourhood. At the bidding of her son, Earl Gerald, she planted all

Knockainey with pease in a single night. She was, and perhaps still is, worshipped

on Midsummer Eve by the peasantry, who carried torches of hay and straw, tied

on poles and lighted, round her hill at night. Afterwards they dispersed

themselves among their cultivated fields and pastures, waving the torches over

the crops and the cattle to bring luck and increase for the following year. On one

night, as told by Mr. D. Fitzgerald,28 who has collected the local traditions

about her, the ceremony was omitted owing to the death of one of the

neighbours. Yet the peasantry at night saw the torches in greater number than

ever circling the hill, and Ainé herself in front, directing and ordering the

procession. “On

another St. John’s Night a number of girls had stayed late on the Hill watching

the cliars (torches) and joining in the games. Suddenly Ainé appeared

among them, thanked them for the honour they had done her, but said she now

wished them to go home, as they wanted the hill to themselves. She let

them understand whom she meant by they, for calling some of the girls she

made them look through a ring, when behold, the hill appeared crowded with

people before invisible.”  “Here,”

observed Mr. Alfred Nutt, “we have the antique ritual carried out on a spot hallowed

to one of the antique powers, watched over and shared in by those powers

themselves. Nowhere save in Gaeldom could be found such a pregnant illustration

of the identity of the fairy class with the venerable powers to ensure whose

goodwill rites and sacrifices, originally fierce and bloody, now a mere

simulacrum of their pristine form, have been performed for countless ages.”29 Sinend and the Well of Knowledge

There

is a singular myth which, while intended to account for the name of the river Shannon,

expresses the Celtic veneration for poetry and science, combined with the

warning that they may not be approached without danger. The goddess Sinend, it

was said, daughter of Lodan son of Lir, went to a certain well named Connla’s

Well, which is under the sea — i.e., in the Land of Youth in Fairyland.

“That is a well,” says the bardic narrative, “at which are the hazels of wisdom

and inspirations, that is, the hazels of the science of poetry, and in the same

hour their fruit and their blossom and their foliage break forth, and then fall

upon the well in the same shower, which raises upon the water a royal surge of

purple.” When Sinend came to the well we are not told what rites or preparation

she had omitted, but the angry waters broke forth and overwhelmed her, and

washed her up on the Shannon shore, where she died, giving to the river its name.30

This myth of the hazels of inspiration and knowledge and their association with

springing water runs through all Irish legend, and has been finely treated by a

living Irish poet, Mr. G.W. Russell, in the following verses: “A cabin on the mountain-side hid in a grassy nook, With door and window

open wide, where friendly stars may look; The rabbit shy may

patter in, the winds may enter free Who roam around the

mountain throne in living ecstasy. “And when the sun sets dimmed in eve, and purple fills the

air, I think the sacred

hazel-tree is dropping berries there, From starry fruitage,

waved aloft where Connla’s Well o’erflows; For sure, the

immortal waters run through every wind that blows. “I think when Night towers up aloft and shakes the trembling

dew, How every high and

lonely thought that thrills my spirit through Is but a shining berry

dropped down through the purple air, And from the magic

tree of life the fruit falls everywhere.”

The Coming of the Milesians

After

the Second Battle of Moytura the Danaans held rule in Ireland until the coming

of the Milesians, the sons of Miled. These are conceived in Irish legend as an

entirely human race, yet in their origin they, like the other invaders of

Ireland, go back to a divine and mythical ancestry. Miled, whose name occurs as

a god in a Celtic inscription from Hungary, is represented as a son of Bilé.

Bilé, like Balor, is one of the names of the god of Death, i.e., of the Underworld. They come from “Spain” — the usual term

employed by the later rationalising historians for the Land of the Dead. The

manner of their coming into Ireland was as follows: Ith, the grandfather of

Miled, dwelt in a great tower which his father, Bregon, had built in “Spain.”

One clear winter’s day, when looking out westwards from this lofty tower, he

saw the coast of Ireland in the distance, and resolved to sail to the unknown

land. He embarked

with ninety warriors, and took land at Corcadyna, in the south-west. In

connexion with this episode I may quote a passage of great beauty and interest

from de Jubainville’s “Irish Mythological Cycle”:31 “According

to an unknown writer cited by Plutarch, who died about the year 120 of the

present era, and also by Procopius, who wrote in the sixth century A.D., ‘the

Land of the Dead’ is the western extremity of Great Britain, separated from the

eastern by an impassable wall. On the northern coast of Gaul, says the legend,

is a populace of mariners whose business is to carry the dead across from the

continent to their last abode in the island of Britain. The mariners, awakened

in the night by the whisperings of some mysterious voice, arise and go down to

the shore, where they find ships awaiting them which are not their own,32

and, in these, invisible beings, under whose weight the vessels sink almost to

the gunwales. They go on board, and with a single stroke of the oar, says one

text, in one hour, says another, they arrive at their destination, though with

their own vessels, aided by sails, it would have taken them at least a day and

a night to reach the coast of Britain. When they come to the other shore the invisible

passengers land, and at the same time the unloaded ships are seen to rise above

the waves, and a voice is heard announcing the names of the new arrivals, who

have just been added to the inhabitants of the Land of the Dead. “One

stroke of the oar, one hour’s voyage at most, suffices for the midnight journey

which transfers the Dead from the Gaulish continent to their final abode. Some

mysterious law, indeed, brings together in the night the great spaces which

divide the domain of the living from that of the dead in daytime. It was the

same law which enabled Ith one fine winter evening to perceive from the Tower

of Bregon, in the Land of the Dead, the shores of Ireland, or the land of the

living. The phenomenon took place in winter; for winter is a sort of night;

winter, like night, lowers the barriers between the regions of Death and those

of Life; like night, winter gives to life the semblance of death, and

suppresses, as it were, the dread abyss that lies between the two.” At

this time, it is said, Ireland was ruled by three Danaan kings, grandsons of

the Dagda. Their names were MacCuill, MacCecht, and MacGrené, and their wives

were named respectively Banba, Fohla, and Eriu. The Celtic habit of conceiving

divine persons in triads is here illustrated. These triads represent one person

each, and the mythical character of that personage is evident from the name of

one of them, MacGrené, Son of the Sun. The names of the three goddesses have

each at different times been applied to Ireland, but that of the third, Eriu,

has alone persisted, and in the dative form, Erinn, is a poetic name for the

country to this day. That Eriu is the wife of MacGrené means, as de Jubainville

observes, that the Sun-god, the god of Day, Life, and Science, has wedded the

land and is reigning over it. Ith, on

landing, finds that the Danaan king, Neit, has just been slain in a battle with

the Fomorians, and the three sons, MacCuill and the others, are at the fortress

of Aileach, in Co. Donegal, arranging for a division of the land among

themselves. At first they welcome Ith, and ask him to settle their inheritance.

Ith gives his judgment, but, in concluding, his admiration for the newly

discovered country breaks out: “Act,” he says, “according to the laws of

justice, for the country you dwell in is a good one, it is rich in fruit and

honey, in wheat and in fish; and in heat and cold it is temperate.” From this

panegyric the Danaans conclude that Ith has designs upon their land, and they

seize him and put him to death. His companions, however, recover his body and

bear it back with them in their ships to “Spain”; when the children of Miled

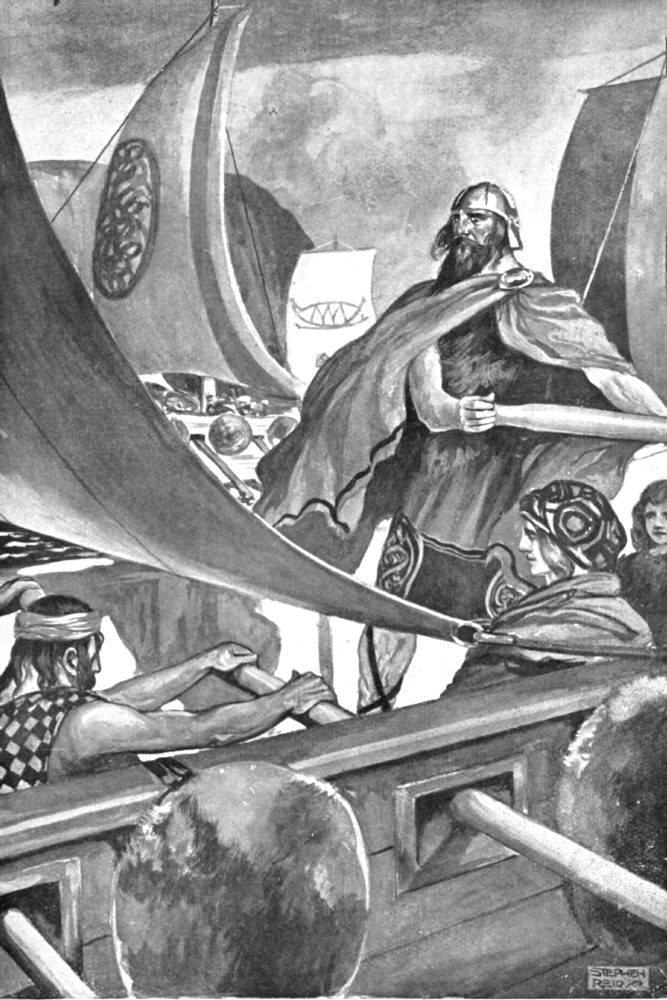

resolve to take vengeance for the outrage and prepare to invade Ireland.  The Coming of the Sons of Miled They

were commanded by thirty-six chiefs, each having his own ship with his family

and his followers. Two of the company are said to have perished on the way. One

of the sons of Miled, having climbed to the masthead of his vessel to look out

for the coast of Ireland, fell into the sea and was drowned. The other was Skena,

wife of the poet Amergin, son of Miled, who died on the way. The Milesians

buried her when they landed, and called the place “Inverskena” after her; this

was the ancient name of the Kenmare River in Co. Kerry. “It

was on a Thursday, the first of May, and the seventeenth day of the moon, that

the sons of Miled arrived in Ireland. Partholan also landed in Ireland on the

first of May, but on a different day of the week and of the moon; and it was on

the first day of May, too, that the pestilence came which in the space of one

week destroyed utterly his race. The first of May was sacred to Beltené, one of

the names of the god of Death, the god who gives life to men and takes it away

from them again. Thus it was on the feast day of this god that the sons of

Miled began their conquest of Ireland.”33 The Poet Amergin

When

the poet Amergin set foot upon the soil of Ireland it is said that he chanted a

strange and mystical lay: “I am the Wind that blows over the sea, I am the Wave of the

Ocean; I am the Murmur of

the billows; I am the Ox of the

Seven Combats; I am the Vulture upon

the rock; I am a Ray of the

Sun; I am the fairest of

Plants; I am a Wild Boar in

valour; I am a Salmon in the

Water; I am a Lake in the

plain; I am the Craft of the

artificer; I am a Word of

Science; I am the Spear-point

that gives battle; I am the god that

creates in the head of man the fire of thought. Who is it that

enlightens the assembly upon the mountain, if not I? Who telleth the ages

of the moon, if not I? Who showeth the place

where the sun goes to rest, if not I? De

Jubainville, whose translation I have in the main followed, observes upon this

strange utterance: “There

is a lack of order in this composition, the ideas, fundamental and subordinate,

are jumbled together without method; but there is no doubt as to the meaning:

the filé [poet] is the Word of Science, he is the god who gives to man

the fire of thought; and as science is not distinct from its object, as God and

Nature are but one, the being of the filé is mingled with the winds and

the waves, with the wild animals and the warrior’s arms.”34 Two

other poems are attributed to Amergin, in which he invokes the land and

physical features of Ireland to aid him:

“I invoke the land of Ireland, Shining, shining sea;

Fertile, fertile

Mountain; Gladed, gladed wood! Abundant river,

abundant in water! Fish-abounding lake!”35 The Judgment of Amergin

The

Milesian host, after landing, advance to Tara, where they find the three kings

of the Danaans awaiting them, and summon them to deliver up the island. The

Danaans ask for three days’ time to consider whether they shall quit Ireland,

or submit, or give battle; and they propose to leave the decision, upon their

request, to Amergin. Amergin pronounces judgment — “the first judgment which

was delivered in Ireland.” He agrees that the Milesians must not take their

foes by surprise — they are to withdraw the length of nine waves from the shore,

and then return; if they then conquer the Danaans the land is to be fairly

theirs by right of battle. The

Milesians submit to this decision and embark on their ships. But no sooner have

they drawn off for this mystical distance of the nine waves than a mist

and storm are raised by the sorceries of the Danaans — the coast of Ireland is

hidden from their sight, and they wander dispersed upon the ocean. To ascertain

if it is a natural or a Druidic tempest which afflicts them, a man named Aranan

is sent up to the masthead to see if the wind is blowing there also or not. He

is flung from the swaying mast, but as he falls to his death he cries his

message to his shipmates: “There is no storm aloft.” Amergin, who as poet — that

is to say, Druid — takes the lead in all critical situations, thereupon chants

his incantation to the land of Erin. The wind falls, and they turn their prows,

rejoicing, towards the shore. But one of the Milesian lords, Eber Donn, exults

in brutal rage at the prospect of putting all the dwellers in Ireland to the

sword; the tempest immediately springs up again, and many of the Milesian ships

founder, Eber Donn’s being among them. At last a remnant of the Milesians find

their way to shore, and land in the estuary of the Boyne. The Defeat of the Danaans

A

great battle with the Danaans at Telltown then follows. The three kings and

three queens of the Danaans, with many of their people, are slain, and the

children of Miled — the last of the mythical invaders of Ireland — enter upon

the sovranty of Ireland. But the People of Dana do not withdraw. By their magic

art they cast over themselves a veil of invisibility, which they can put on or

off as they choose. There are two Irelands henceforward, the spiritual and the

earthly. The Danaans dwell in the spiritual Ireland, which is portioned out

among them by their great overlord, the Dagda. Where the human eye can see but

green mounds and ramparts, the relics of ruined fortresses or sepulchres, there

rise the fairy palaces of the defeated divinities; there they hold their revels

in eternal sunshine, nourished by the magic meat and ale that give them undying

youth and beauty; and thence they come forth at times to mingle with mortal men

in love or in war. The ancient mythical literature conceives them as heroic and

splendid in strength and beauty. In later times, and as Christian influences

grew stronger, they dwindle into fairies, the People of the Sidhe;37

but they have never wholly perished; to this day the Land of Youth and its inhabitants

live in the imagination of the Irish peasant.

The Meaning of the Danaan Myth

All

myths constructed by a primitive people are symbols, and if we can discover

what it is that they symbolise we have a valuable clue to the spiritual character,

and sometimes even to the history, of the people from whom they sprang. Now the

meaning of the Danaan myth as it appears in the bardic literature, though it

has undergone much distortion before it reached us, is perfectly clear. The

Danaans represent the Celtic reverence for science, poetry, and artistic skill,

blended, of course, with the earlier conception of the divinity of the powers

of Light. In their combat with the Firbolgs the victory of the intellect over

dulness and ignorance is plainly portrayed — the comparison of the heavy, blunt

weapon of the Firbolgs with the light and penetrating spears of the People of

Dana is an indication which it is impossible to mistake. Again, in their

struggle with a far more powerful and dangerous enemy, the Fomorians, we are evidently

to see the combat of the powers of Light with evil of a more positive kind than

that represented by the Firbolgs. The Fomorians stand not for mere dulness or

stupidity, but for the forces of tyranny, cruelty, and greed — for moral rather

than for intellectual darkness. The Meaning of the Milesian Myth

But

the myth of the struggle of the Danaans with the sons of Miled is more difficult

to interpret. How does it come that the lords of light and beauty, wielding all

the powers of thought (represented by magic and sorcery), succumbed to a human

race, and were dispossessed by them of their hard-won inheritance? What is the

meaning of this shrinking of their powers which at once took place when the

Milesians came on the scene? The Milesians were not on the side of the powers

of darkness. They were guided by Amergin, a clear embodiment of the idea of

poetry and thought. They were regarded with the utmost veneration, and the

dominant families of Ireland all traced their descent to them. Was the Kingdom

of Light, then, divided against itself? Or, if not, to what conception in the

Irish mind are we to trace the myth of the Milesian invasion and victory? The

only answer I can see to this puzzling question is to suppose that the Milesian

myth originated at a much later time than the others, and was, in its main

features, the product of Christian influences. The People of Dana were in

possession of the country, but they were pagan divinities — they could not

stand for the progenitors of a Christian Ireland. They had somehow or other to

be got rid of, and a race of less embarrassing antecedents substituted for

them. So the Milesians were fetched from “Spain” and endowed with the main

characteristics, only more humanised, of the People of Dana. But the latter, in

contradistinction to the usual attitude of early Christianity, are treated very

tenderly in the story of their overthrow. One of them has the honour of giving

her name to the island, the brutality of one of the conquerors towards them is

punished with death, and while dispossessed of the lordship of the soil they

still enjoy life in the fair world which by their magic art they have made invisible

to mortals. They are no longer gods, but they are more than human, and frequent

instances occur in which they are shown as coming forth from their fairy world,

being embraced in the Christian fold, and entering into heavenly bliss. With

two cases of this redemption of the Danaans we shall close this chapter on the

Invasion Myths of Ireland. The

first is the strange and beautiful tale of the Transformation of the Children

of Lir. The Children of Lir

Lir

was a Danaan divinity, the father of the sea-god Mananan who continually occurs