| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XI THE SEARCH CONTINUED MACHU PICCHU is on

the

border-line between the

temperate zone and the tropics. Camping near the bridge of San Miguel,

below

the ruins, both Mr. Heller and Mr. Cook found interesting evidences of

this

fact in the flora and fauna. From the point of view of historical

geography,

Mr. Cook’s most important discovery was the presence here of huilca, a

tree

which does not grow in cold climates. The Quichua dictionaries tell us huilca is a “medicine, a purgative.” An

infusion made from the seeds of the tree is used as an enema. I am

indebted to

Mr. Cook for calling my attention to two articles by Mr. W. E. Safford

in which

it is also shown that from seeds of the huilca

a powder is prepared, sometimes called cohoba.

This powder, says Mr. Safford, is a narcotic snuff

“inhaled through the

nostrils by means of a bifurcated tube.” “All writers unite in

declaring that

it induced a kind of intoxication or hypnotic state, accompanied by

visions

which were regarded by the natives as supernatural. While under its

influence

the necromancers, or priests, were supposed to hold communication with

unseen

powers, and their incoherent mutterings were regarded as prophecies or

revelations of hidden things. In treating the sick the physicians made

use of

it to discover the cause of the malady or the person or spirit by whom

the

patient was bewitched.” Mr. Safford quotes Las Casas as saying: “It was

an

interesting spectacle to witness how they took it and what they spake.

The

chief began the ceremony and while he was engaged all remained

silent.... When

he had snuffed up the powder through his nostrils, he remained silent

for a

while with his head inclined to one side and his arms placed on his

knees. Then

he raised his face heavenward, uttering certain words which must have

been his

prayer to the true God, or to him whom he held as God; after which all

responded,

almost as we do when we say amen; and this they did with a loud voice

or sound.

Then they gave thanks and said to him certain complimentary things,

entreating

his benevolence and begging him to reveal to them what he had seen. He

described to them his vision, saying that the Cemi [spirits] had spoken

to him

and had predicted good times or the contrary, or that children were to

be born,

or to die, or that there was to be some dispute with their neighbors,

and other

things which might come to his imagination, all disturbed with that

intoxication.”1 Clearly, from the

point of view

of priests and

soothsayers, the place where huilca was first found

and used in their

incantations would be important. It is not strange to find therefore

that the

Inca name of this river was Uilca-mayu:

the “huilca river.” The pampa on

this river where the trees grew

would likely receive the name Uilca pampa. If it

became an important

city, then the surrounding region might be named Uilcapampa

after it. This seems to me to be the most probable

origin of the name of the province. Anyhow it is worth noting the fact

that

denizens of Cuzco and Ollantaytambo, coming down the river in search of

this

highly prized narcotic, must have found the first trees not far from

Machu

Picchu. Leaving the ruins of

Machu

Picchu for later

investigation, we now pushed on down the Urubamba Valley, crossed the

bridge of

San Miguel, passed the house of Señor Lizarraga, first of modern

Peruvians to

write his name on the granite walls of Machu Picchu, and came to the

sugarcane

fields of Huadquina. We had now left the temperate zone and entered the

tropics. At Huadquina we were

so

fortunate as to find that

the proprietress of the plantation, Señora Carmen Vargas, and her

children,

were spending the season here. During the rainy winter months they live

in

Cuzco, but when summer brings fine weather they come to Huadquina to

enjoy the

free-and-easy life of the country. They made us welcome, not only with

that

hospitality to passing travelers which is common to sugar estates all

over the

world, but gave us real assistance in our explorations. Señora Carmen’s

estate

covers more than two hundred square miles. Huadquina is a splendid

example of

the ancient patriarchal system. The Indians who come from other parts

of Peru

to work on the plantation enjoy perquisites and wages unknown

elsewhere. Those

whose home is on the estate regard Señora Carmen with an affectionate

reverence

which she well deserves. All are welcome to bring her their troubles.

The

system goes back to the days when the spiritual, moral, and material

welfare of

the Indians was entrusted in encomieda

to the lords of the repartimiento

or

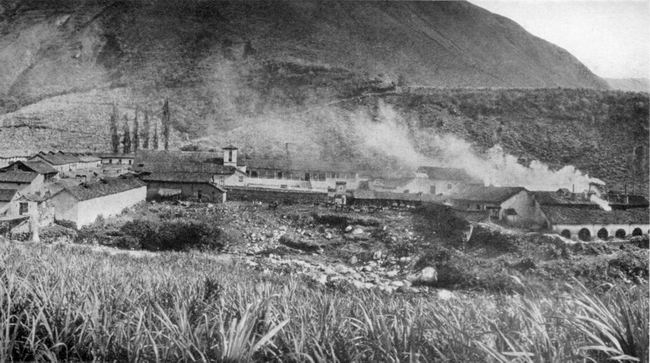

allotted territory.  HUADQUIÑA Huadquina once

belonged to the

Jesuits. They planted

the first sugar cane and established the mill. After their expulsion

from the

Spanish colonies at the end of the eighteenth century, Huadquina was

bought by

a Peruvian. It was first described in geographical literature by the

Count de

Sartiges, who stayed here for several weeks in 1834 when on his way to

Choqquequirau. He says that the owner of Huadquina “is perhaps the only

landed

proprietor in the entire world who possesses on his estates all the

products of

the four parts of the globe. In the different regions of his domain he

has

wool, hides, horsehair, potatoes, wheat, corn, sugar, coffee,

chocolate, coca, many

mines of silver-bearing lead, and

placers of gold.” Truly a royal principality. Incidentally it is

interesting

to note that although

Sartiges was an enthusiastic explorer, eager to visit undescribed Inca

ruins,

he makes no mention what-ever of Machu Picchu. Yet from Huadquina one

can reach

Machu Picchu on foot in half a day without crossing the Urubamba River.

Apparently the ruins were unknown to his hosts in 1834. They were

equally unknown

to our kind hosts in 1911. They scarcely believed the story I told them

of the

beauty and extent of the Inca edifices.2 When my

photographs were

developed, however, and they saw with their own eyes the marvelous

stonework of

the principal temples, Señora Carmen and her family were struck dumb

with

wonder and astonishment. They could not understand how it was possible

that

they should have passed so close to Machu Picchu every year of their

lives

since the river road was opened without knowing what was there. They

had seen a

single little building on the crest of the ridge, but supposed that it

was an

isolated tower of no great interest or importance. Their neighbor,

Lizarraga,

near the bridge of San Miguel, had reported the presence of the ruins

which he first

visited in 1904, but, like our friends in Cuzco, they had paid little

attention

to his stories. We were soon to have a demonstration of the causes of

such

skepticism. Our new friends read

with

interest my copy of those

paragraphs of Calancha’s “Chronicle” which referred to the location of

the last

Inca capital. Learning that we were anxious to discover Uiticos, a

place of

which they had never heard, they ordered the most intelligent tenants

on the

estate to come in and be questioned. The best informed of all was a

sturdy

mestizo, a trusted foreman, who said that in a little valley called

Ccllumayu,

a few hours’ journey down the Urubamba, there were “important ruins”

which had

been seen by some of Señora Carmen’s Indians. Even more interesting and

thrilling

was his statement that on a ridge up the Salcantay Valley was a place

called

Yurak Rumi (yurak = “white”; rumi =

“stone”) where some very

interesting ruins had been found by his workmen when cutting trees for

firewood. We all became excited over this, for among the paragraphs

which I had

copied from Calancha’s “Chronicle”

was

the statement that “close to Uiticos” is the “white stone of the

aforesaid

house of the Sun which is called Yurak Rumi.” Our hosts assured us that

this

must be the place, since no one hereabouts had ever heard of any other

Yurak

Rumi. The foreman, on being closely questioned, said that he had seen

the ruins

once or twice, that he had also been up the Urubamba Valley and seen

the great

ruins at Ollantaytambo, and that those which he had seen at Yurak Rumi

were “as

good as those at Ollantaytambo.” Here was a definite statement made by

an

eyewitness. Apparently we were about to see that interesting rock where

the

last Incas worshiped. However, the foreman said that the trail thither

was at

present impassable, although a small gang of Indians could open it in

less than

a week. Our hosts, excited by the pictures we had shown them of Machu

Picchu,

and now believing that even finer ruins might be found on their own

property,

immediately gave orders to have the path to Yurak Rumi cleared for our

benefit. While this was being

done,

Señora Carmen’s son, the

manager of the plantation, offered to accompany us himself to

Ccllumayu, where

other “important ruins” had been found, which could be reached in a few

hours

without cutting any new trails. Acting on his assurance that we should

not need

tent or cots, we left our camping outfit behind and followed him to a

small

valley on the south side of the Urubamba. We found Ccllumayu to consist

of two

huts in a small clearing. Densely wooded slopes rose on all sides. The

manager

requested two of the Indian tenants to act as guides. With them, we

plunged

into the thick jungle and spent a long and fatiguing day searching in

vain for

ruins. That night the manager returned to Huadquina, but Professor

Foote and I

preferred to remain in Ccllumayu and prosecute a more vigorous search

on the

next day. We shared a little thatched hut with our Indian hosts and a

score of

fat cuys (guinea pigs), the chief

source of the Ccllumayu meat supply. The hut was built of rough wattles

which

admitted plenty of fresh air and gave us comfortable ventilation.

Primitive

little sleeping-platforms, also of wattles, constructed for the needs

of short,

stocky Indians, kept us from being overrun by inquisitive cuys,

but could hardly be called as

comfortable as our own folding

cots which we had left at Huadquina. The next day our

guides were

able to point out in

the woods a few piles of stones, the foundations of oval or circular

huts which

probably were built by some primitive savage tribe in prehistoric

times.

Nothing further could be found here of ruins, “important” or otherwise,

although we spent three days at Ccllumayu. Such was our first

disillusionment. On our return to

Huadquina, we

learned that the

trail to Yurak Rumi would be ready “in a day or two.” In the meantime

our hosts

became much interested in Professor Foote’s collection of insects. They brought an

unnamed

scorpion and informed us

that an orange orchard surrounded by high walls in a secluded place

back of the

house was “a great place for spiders.” We found that their statement

was not

exaggerated and immediately engaged in an enthusiastic spider hunt.

When these

Huadquina spiders were studied at the Harvard Museum of Comparative

Zoology,

Dr. Chamberlain found among them the representatives of four new genera

and

nineteen species hitherto unknown to science. As a reward of merit, he

gave

Professor Foote’s name to the scorpion! Finally the trail to

Yurak Rumi

was reported finished.

It was with feelings of keen anticipation that I started out with the

foreman

to see those ruins which he had just revisited and now declared were

“better

than those of Ollantaytambo.” It was to be presumed that in the pride

of

discovery he might have exaggerated their importance. Still it never

entered my

head what I was actually to find. After several hours spent in clearing

away

the dense forest growth which surrounded the walls I learned that this

Yurak

Rumi consisted of the ruins of a single little rectangular Inca

storehouse. No

effort had been made at beauty of construction. The walls were of

rough,

unfashioned stones laid in clay. The building was without a doorway,

although

it had several small windows and a series of ventilating shafts under

the

house. The lintels of the windows and of the small apertures leading

into the

subterranean shafts were of stone. There were no windows on the sunny

north

side or on the ends, but there were four on the south side through

which it

would have been possible to secure access to the stores of maize,

potatoes, or

other provisions placed here for safe-keeping. It will be recalled that

the

Incas maintained an extensive system of public storehouses, not only in

the

centers of population, but also at strategic points on the principal

trails.

Yurak Rumi is on top of the ridge between the Salcantay and Huadquina

valleys,

probably on an ancient road which crossed the province of Uilcapampa.

As such

it was interesting; but to compare it with Ollantaytambo, as the

foreman had

done, was to liken a cottage to a palace or a mouse to an elephant. It

seems

incredible that anybody having actually seen both places could have

thought for

a moment that one was “as good as the other.” To be sure, the foreman

was not a

trained observer and his interest in Inca buildings was probably of the

slightest. Yet the ruins of Ollantaytambo are so well known and so

impressive

that even the most casual traveler is struck by them and the natives

themselves

are enormously proud of them. The real cause of the foreman’s

inaccuracy was

probably his desire to please. To give an answer which will satisfy the

questioner is a common trait in Peru as well as in many other parts of

the

world. Anyhow, the lessons of the past few days were not lost on us. We

now

understood the skepticism which had prevailed regarding Lizarraga’s

discoveries. It is small wonder that the occasional stories about Machu

Picchu

which had drifted into Cuzco had never elicited any enthusiasm nor even

provoked investigation on the part of those professors and students in

the

University of Cuzco who were interested in visiting the remains of Inca

civilization. They knew only too well the fondness of their countrymen

for

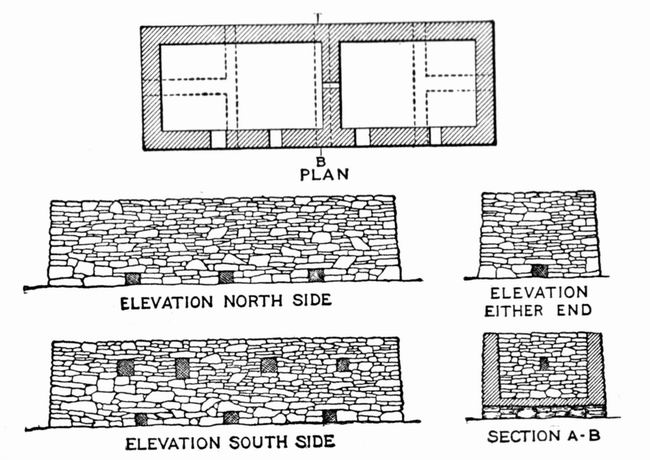

exaggeration and their inability to report facts accurately.  Ruins of YURAK RUMI near Huadquiña. Probably an Inca Storehouse, well ventilated and well drained. Drawn by A. H. Bumstead from measurements and photographs by Hiram Bingham and H. W. Foote. Obviously, we had not

yet found

Uiticos. So, bidding

farewell to Señora Carmen, we crossed the Urubamba on the bridge of

Colpani and

proceeded down the valley past the mouth of the Lucumayo and the road

from

Panticalla, to the hamlet of Chauillay, where the Urubamba is joined by

the

Vilcabamba River.3 Both rivers are restricted here to narrow gorges,

through

which their waters rush and roar on their way to the lower valley. A

few rods

from Chauillay was a fine bridge. The natives call it Chuquichaca!

Steel and

iron have superseded the old suspension bridge of huge cables made of

vegetable

fiber, with its narrow roadway of wattles supported by a network of

vines. Yet

here it was that in 1572 the military force sent by the viceroy,

Francisco de

Toledo, under the command of General Martin Hurtado and Captain Garcia,

found

the forces of the young Inca drawn up to defend Uiticos. It will be

remembered

that after a brief preliminary fire the forces of Tupac Amaru were

routed

without having destroyed the bridge and thus Captain Garcia was enabled

to

accomplish that which had proved too much for the famous Gonzalo

Pizarro. Our

inspection of the surroundings showed that Captain Garcia’s companion,

Baltasar

de Ocampo, was correct when he said that the occupation of the bridge

of

Chuquichaca “was a measure of no small importance for the royal force.”

It

certainly would have caused the Spaniards “great trouble” if they had

had to

rebuild it. We might now have

proceeded to

follow Garcia’s

tracks up the Vilcabamba had we not been anxious to see the proprietor

of the

plantation of Santa Ana, Don Pedro Duque, reputed to be the wisest and

ablest

man in this whole province. We felt he would be able to offer us advice

of

prime importance in our search. So leaving the bridge of Chuquichaca,

we

continued down the Urubamba River which here meanders through a broad,

fertile

valley, green with tropical plantations. We passed groves of bananas

and

oranges, waving fields of green sugar cane, the hospitable dwellings of

prosperous planters, and the huts of Indians fortunate enough to dwell

in this

tropical “Garden of Eden.” The day was hot and thirst-provoking, so I

stopped

near some large orange trees loaded with ripe fruit and asked the

Indian

proprietress to sell me ten cents’ worth. In exchange for the tiny

silver real she dragged out a sack

containing

more than fifty oranges! I was fain to request her to permit us to take

only as

many as our pockets could hold; but she seemed so surprised and pained,

we had

to fill our saddle-bags as well. At the end of the day

we

crossed the Urubamba River

on a fine steel bridge and found ourselves in the prosperous little

town of

Quillabamba, the provincial capital. Its main street was lined with

well-filled

shops, evidence of the fact that this is one of the principal gateways

to the

Peruvian rubber country which, with the high price of rubber then

prevailing,

1911, was the scene of unusual activity. Passing through Quillabamba

and up a

slight hill beyond it, we came to the long colonnades of the celebrated

sugar

estate of Santa Ana founded by the Jesuits, where all explorers who

have passed

this way since the days of Charles Wiener have been entertained. He

says that

he was received here “with a thousand signs of friendship” (“mille

temoignages d’amitie”). We were received the same

way. Even in

a region where we had repeatedly received valuable assistance from

government

officials and generous hospitality from private individuals, our

reception at

Santa Ana stands out as particularly delightful. Don Pedro Duque took

great

interest in enabling us

to get all possible information about the little-known region into

which we

proposed to penetrate. Born in Colombia, but long resident in Peru, he

was a

gentleman of the old school, keenly interested, not only in the

administration

and economic progress of his plantation, but also in the intellectual

movements

of the outside world. He entered with zest into our

historical-geographical

studies. The name Uiticos was new to him, but after reading over with

us our

extracts from the Spanish chronicles he was sure that he could help us

find it.

And help us he did. Santa Ana is less than thirteen degrees south of

the

equator; the elevation is barely 2000 feet; the “winter” nights are

cool; but

the heat in the middle of the day is intense. Nevertheless, our host

was so

energetic that as a result of his efforts a number of the best-informed

residents were brought to the conferences at the great plantation

house. They

told all they knew of the towns and valleys where the last four Incas

had found

a refuge, but that was not much. They all agreed that “if only Señor

Lopez

Torres were alive he could have been of great service” to us, as “he

had

prospected for mines and rubber in those parts more than any one else,

and had

once seen some Inca ruins in the forest!” Of Uiticos and Chuquipalpa

and most

of the places mentioned in the chronicles, none of Don Pedro’s friends

had ever

heard. It was all rather discouraging, until one day, by the greatest

good

fortune, there arrived at Santa Ana another friend of Don Pedro’s, the teniente gobernador of the village of

Lucma in the valley of Vilcabamba — a crusty old fellow named Evaristo

Mogrovejo. His brother, Pio Mogrovejo, had been a member of the party

of

energetic Peruvians who, in 1884, had searched for buried treasure at

Choqquequirau and had left their names on its walls. Evaristo Mogrovejo

could

understand searching for buried treasure, but he was totally unable

otherwise

to comprehend our desire to find the ruins of the places mentioned by

Father

Calancha and the contemporaries of Captain Garcia. Had we first met

Mogrovejo

in Lucma he would undoubtedly have received us with suspicion and done

nothing

to further our quest. Fortunately for us, his official superior was the

sub-prefect of the province of Convencion, lived at Quillabamba near

Santa Ana,

and was a friend of Don Pedro’s. The sub-prefect had received orders

from his

own official superior, the prefect of Cuzco, to take a personal

interest in our

undertaking, and accordingly gave particular orders to Mogrovejo to see

to it

that we were given every facility for finding the ancient ruins and

identifying

the places of historic interest. Although Mogrovejo declined to risk

his skin

in the savage wilderness of Conservidayoc, he carried out his orders

faithfully

and was ultimately of great assistance to us. Extremely gratified

with the

result of our

conferences in Santa Ana, yet reluctant to leave the delightful

hospitality and

charming conversation of our gracious host, we decided to go at once to

Lucma,

taking the road on the southwest side of the Urubamba and using the

route

followed by the pack animals which carry the precious cargoes of coca and aguardiente

from Santa Ana to Ollantaytambo and Cuzco. Thanks to

Don Pedro’s energy, we made an excellent start; not one of those

meant-to-be-early but really late-in-the-morning departures so

customary in the

Andes. We passed through a

region

which originally had been

heavily forested, had long since been cleared, and was now covered with

bushes

and second growth. Near the roadside I noticed a considerable number of

land

shells grouped on the under-side of overhanging rocks. As a boy in the

Hawaiian

Islands I had spent too many Saturdays collecting those beautiful and

fascinating mollusks, which usually prefer the trees of upland valleys,

to

enable me to resist the temptation of gathering a large number of such

as could

easily be secured. None of the snails were moving. The dry season

appears to be

their resting period. Some weeks later Professor Foote and I passed

through

Maras and were interested to notice thousands of land shells, mostly

white in

color, on small bushes, where they seemed to be quietly sleeping. They

were

fairly “glued to their resting places”; clustered so closely in some

cases as

to give the stems of the bushes a ghostly appearance. Our present

objective was

the valley of the river Vilcabamba. So far as we have been able to

learn, only

one other explorer had preceded us — the distinguished scientist

Raimondi. His

map of the Vilcabamba is fairly accurate. He reports the presence here

of mines

and minerals, but with the exception of an “abandoned tampu”

at Maracnyoc (“the place which possesses a millstone”),

he

makes no mention of any ruins. Accordingly, although it seemed from the

story

of Baltasar de Ocampo and Captain Garcia’s other contemporaries that we

were

now entering the valley of Uiticos, it was with feelings of

considerable

uncertainty that we proceeded on our quest. It may seem strange that we

should

have been in any doubt. Yet before our visit nearly all the Peruvian

historians

and geographers except Don Carlos Romero still believed that when the

Inca

Manco fled from Pizarro he took up his residence at Choqquequirau in

the

Apurimac Valley. The word choqquequirau means

“cradle of gold” and this lent color to the legend that Manco had

carried off

with him from Cuzco great quantities of gold utensils and much

treasure, which

he deposited in his new capital. Raimondi, knowing that Manco had

“retired to

Uilcapampa,” visited both the present villages of Vilcabamba and

Pucyura and

saw nothing of any ruins. He was satisfied that Choqquequirau was

Manco’s

refuge because it was far enough from Pucyura to answer the

requirements of

Calancha that it was “two or three days’ journey” from Uilcapampa to

Puquiura. A new road had

recently been

built along the river

bank by the owner of the sugar estate at Paltaybamba, to enable his

pack

animals to travel more rapidly. Much of it had to be carved out of the

face of

a solid rock precipice and in places it pierces the cliffs in a series

of

little tunnels. My gendarme missed

this road and took the steep old trail over the cliffs. As Ocampo said

in his

story of Captain Garcia’s expedition, “the road was narrow in the

ascent with

forest on the right, and on the left a ravine of great depth.” We

reached

Paltaybamba about dusk. The owner, Señor José S. Pancorbo, was absent,

attending to the affairs of a rubber estate in the jungles of the river

San

Miguel. The plantation of Paltaybamba occupies the best lands in the

lower

Vilcabamba Valley, but lying, as it does, well off the main highway,

visitors

are rare and our arrival was the occasion for considerable excitement.

We were

not unexpected, however. It was Señor Pancorbo who had assured us in

Cuzco that

we should find ruins near Pucyura and he had told his major-domo to be

on the

look-out for us. We had a long talk with the manager of the plantation

and his

friends that evening. They had heard little of any ruins in this

vicinity, but

repeated one of the stories we had heard in Santa Ana, that way off

somewhere

in the montãna there was “an Inca

city.” All agreed that it was a very difficult place to reach; and none

of them

had ever been there. In the morning the manager gave us a guide to the

next house

up the valley, with orders that the man at that house should relay us

to the

next, and so on. These people, all tenants of the plantation,

obligingly

carried out their orders, although at considerable inconvenience to

themselves. The Vilcabamba Valley

above

Paltaybamba is very

picturesque. There are high mountains on either side, covered with

dense jungle

and dark green foliage, in pleasing contrast to the light green of the

fields

of waving sugar cane. The valley is steep, the road is very winding,

and the

torrent of the Vilcabamba roars loudly, even in July. What it must be

like in

February, the rainy season, we could only surmise. About two leagues

above

Paltaybamba, at or near the spot called by Raimondi “Maracnyoc,” an

“abandoned tampu,” we came to some

old stone walls,

the ruins of a place now called Huayara or “Hoyara.” I believe them to

be the

ruins of the first Spanish settlement in this region, a place referred

to by

Ocampo, who says that the fugitives of Tupac Amaru’s army were “brought

back to

the valley of Hoyara,” where they were “settled in a large village, and

a city

of Spaniards was founded.... This city was founded on an extensive

plain near a

river, with an admirable climate. From the river channels of water were

taken

for the service of the city, the water being very good.” The water here

is

excellent, far better than any in the Cuzco Basin. On the plain near

the river

are some of the last cane fields of the plantation of Paltaybamba.

“Hoyara” was

abandoned after the discovery of gold mines several leagues farther up

the

valley, and the Spanish “city” was moved to the village now called

Vilcabamba. Our next stop was at

Lucma, the

home of Teniente Gobernador Mogrovejo.

The

village of Lucma is an irregular cluster of about thirty

thatched-roofed huts.

It enjoys a moderate amount of prosperity due to the fact of its being

located

near one of the gateways to the interior, the pass to the rubber

estates in the

San Miguel Valley. Here are “houses of refreshment” and two shops, the

only

ones in the region. One can buy cotton cloth, sugar, canned goods and

candles.

A picturesque belfry and a small church, old and somewhat out of

repair, crown

the small hill back of the village. There is little level land, but the

slopes

are gentle, and permit a considerable amount of agriculture. There was no evidence

of

extensive terracing. Maize

and alfalfa seemed to be the principal crops. Evaristo Mogrovejo lived

on the

little plaza around which the houses of the more important people were

grouped.

He had just returned from Santa Ana by the way of Idma, using a much

worse

trail than that over which we had come, but one which enabled him to

avoid

passing through Paltaybamba, with whose proprietor he was not on good

terms. He

told us stories of misadventures which had happened to travelers at the

gates

of Paltaybamba, stories highly reminiscent of feudal days in Europe,

when

provincial barons were accustomed to lay tribute on all who passed. We offered to pay

Mogrovejo a gratificación of a sol,

or Peruvian silver dollar, for every ruin to which he would take us,

and double

that amount if the locality should prove to contain particularly

interesting

ruins. This aroused all his business instincts. He summoned his alcaldes and other well-informed Indians

to appear and be interviewed. They told us there were “many ruins”

hereabouts!

Being a practical man himself, Mogrovejo had never taken any interest

in ruins.

Now he saw the chance not only to make money out of the ancient sites,

but also

to gain official favor by carrying out with unexampled vigor the orders

of his

superior, the sub-prefect of Quillabamba. So he exerted himself to the

utmost

in our behalf. The next day we were

guided up

a ravine to the top

of the ridge back of Lucma. This ridge divides the upper from the lower

Vilcabamba. On all sides the hills rose several thousand feet above us.

In

places they were covered with forest growth, chiefly above the cloud

line,

where daily moisture encourages vegetation. In some of the forests on

the more

gentle slopes recent clearings gave evidence of enterprise on the part

of the

present inhabitants of the valley. After an hour’s climb we reached

what were

unquestionably the ruins of Inca structures, on an artificial terrace

which

commands a magnificent view far down toward Paltaybamba and the bridge

of

Chuquichaca, as well as in the opposite direction. The contemporaries

of

Captain Garcia speak of a number of forts or pucáras which had

to be stormed and captured before Tupac Amaru could be taken prisoner.

This was

probably one of those “fortresses.” Its strategic position and the ease

with

which it could be defended point to such an interpretation.

Nevertheless this

ruin did not fit the “fortress of Pitcos,” nor the “House of the Sun”

near the

“white rock over the spring.” It is called Incahuaracana,

“the place where the Inca

shoots with a sling.” Incahuaracana

consists of two

typical Inca edifices

— one of two rooms, about 70 by 20 feet, and the other, very long and

narrow,

150 by 11 feet. The walls, of unhewn stone laid in clay, were not

particularly

well built and resemble in many respects the ruins at Choqquequirau.

The rooms

of the principal house are without windows, although each has three

front doors

and is lined with niches, four or five on a side. The long, narrow

building was

divided into three rooms, and had several front doors. A force of two

hundred

Indian soldiers could have slept in these houses without unusual

crowding. We left Lucma the

next day,

forded the Vilcabamba

River and soon had an uninterrupted view up the valley to a high,

truncated

hill, its top partly covered with a scrubby growth of trees and bushes,

its

sides steep and rocky. We were told that the name of the hill was

“Rosaspata,”

a word of modern hybrid origin — pata being

Quichua for “hill,” while rosas is

the Spanish word for “roses.” Mogrovejo said his

Indians told him that on

the “Hill of Roses” there were more ruins. At the foot of the

hill, and

across the river, is

the village of Pucyura. When Raimondi was here in 1865 it was but a

“wretched hamlet

with a paltry chapel.” To-day it is more prosperous. There is a large

public

school here, to which children come from villages many miles away. So

crowded

is the school that in fine weather the children sit on benches out of

doors.

The boys all go barefooted. The girls wear high boots. I once saw them

reciting

a geography lesson, but I doubt if even the teacher knew whether or not

this

was the site of the first school in this whole region. For it was to

“Puquiura”

that Friar Marcos came in 1566. Perhaps he built the “mezquina capilla”

which

Raimondi scorned. If this were the “Puquiura” of Friar Marcos, then

Uiticos

must be near by, for he and Friar Diego walked with their famous

procession of

converts from “Puquiura” to the House of the Sun and the “white rock”

which was

“close to Uiticos.”  PUCYURA AND THE HILL OF ROSASPATA IN THE VILCABAMBA VALLEY Crossing the

Vilcabamba on a

footbridge that

afternoon, we came immediately upon some old ruins that were not

Incaic.

Examination showed that they were apparently the remains of a very

crude

Spanish crushing mill, obviously intended to pulverize gold-bearing

quartz on a

considerable scale. Perhaps this was the place referred to by Ocampo,

who says

that the Inca Titu Cusi attended masses said by his friend Friar Diego

in a

chapel which is “near my houses and on my own lands, in the mining

district of

Puquiura, close to the ore-crushing mill of Don Christoval de Albornoz,

Precentor that was of the Cuzco Cathedral.” One of the millstones

is five

feet in diameter and

more than a foot thick. It lay near a huge, flat rock of white granite,

hollowed out so as to enable the millstone to be rolled slowly around

in a

hollow trough. There was also a very large Indian mortar and pestle,

heavy

enough to need the services of four men to work it. The mortar was

merely the

hollowed-out top of a large boulder which projected a few inches above

the

surface of the ground. The pestle, four feet in diameter, was of the

characteristic rocking-stone shape used from time immemorial by the

Indians of

the highlands for crushing maize or potatoes. Since no other ruins of a

Spanish

quartz-crushing plant have been found in this vicinity, it is probable

that

this once belonged to Don Christoval de Albornoz. Near the mill the

Tincochaca

River joins the

Vilcabamba from the southeast. Crossing this on a footbridge, I

followed

Mogrovejo to an old and very dilapidated structure in the saddle of the

hill on

the south side of Rosaspata. They called the place Uncapampa, or Inca

pampa.

It is probably one of the forts stormed by Captain Garcia and his men

in 1571.

The ruins represent a single house, 166 feet long by 33 feet wide. If

the house

had partitions they long since disappeared. There were six doorways in

front,

none on the ends or in the rear walls. The ruins resembled those of

Incahuaracana, near Lucma. The walls had originally been built of rough

stones

laid in clay. The general finish was extremely rough. The few niches,

all at

one end of the structure, were irregular, about two feet in width and a

little

more than this in height. The one corner of the building which was

still

standing had a height of about ten feet. Two hundred Inca soldiers

could have

slept here also. Leaving Uncapampa and

following

my guides, I climbed

up the ridge and followed a path along

its west side to the top of Rosaspata. Passing some

ruins much overgrown

and of a primitive character, I soon found myself on a pleasant

pampa

near the top of the mountain. The view from here commands “a great part

of the

province of Uilcapampa.” It is remarkably extensive on all sides; to

the north

and south are snow-capped mountains, to the east and west, deep

verdure-clad

valleys. Furthermore, on the

north side

of the pampa

is an extensive level space with a very sumptuous and majestic building

“erected with great skill and art, all the lintels of the doors, the

principal

as well as the ordinary ones,” being of white granite elaborately cut.

At last

we had found a place which seemed to meet most of the requirements of

Ocampo’s

description of the “fortress of Pitcos.” To be sure it was not of

“marble,” and

the lintels of the doors were not “carved,” in our sense of the word.

They

were, however, beautifully finished, as may be seen from the

illustrations, and

the white granite might easily pass for marble. If only we could find

in this

vicinity that Temple of the Sun which Calancha said was “near” Uiticos,

all

doubts would be at an end. That night we stayed

at

Tincochaca, in the hut of an

Indian friend of Mogrovejo. As usual we made inquiries. Imagine our

feelings

when in response to the oft-repeated question he said that in a

neighboring

valley there was a great white rock over a spring of water! If his

story should

prove to be true our quest for Uiticos was over. It behooved us to make

a very

careful study of what we had found. ________________________

1 Mr.

Safford says in his article on the “Identity of Cohoba” (Journal

of the Washington Academy of Sciences, Sept. 19, 1916):

“The most remarkable fact connected with Piptadenia

peregrina, or ‘tree-tobacco’ is that... the source of its

intoxicating

properties still remains unknown.” One of the bifurcated tubes, “in the

first

stages of manufacture,” was found at Machu Picchu. 2 See

the illustrations in Chapters XVII and XVIII. 3

Since the historical Uilcapampa is not geographically identical with

the modern

Vilcabamba, the name applied to this river and the old Spanish town at

its

source, I shall distinguish between the two by using the correct,

official

spelling for the river and town, viz., Vilcabamba; and the phonetic

spelling,

Uilcapampa, for the place referred to in the contemporary histories of

the Inca

Manco. |