| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

X SEARCHING FOR THE LAST INCA CAPITAL THE events described

in the

preceding chapter

happened, for the most part, in Uiticos 1 and

Uilcapampa, northwest of

Ollantaytambo, about one hundred miles away from the Cuzco palace of

the

Spanish viceroy, in what Prescott calls “the remote fastnesses of the

Andes.”

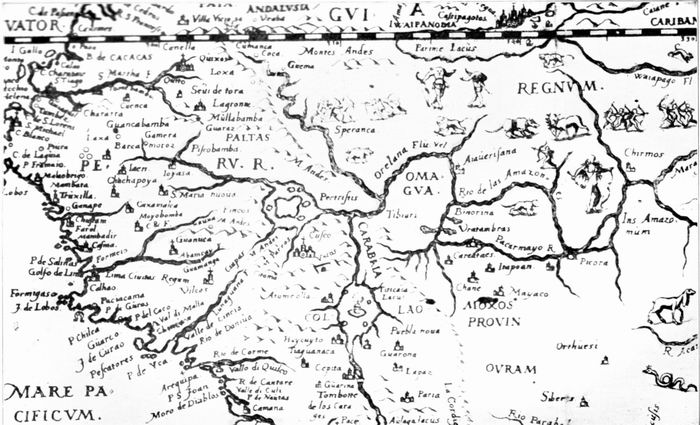

One looks in vain for Uiticos on modern maps of Peru, although several

of the

older maps give it. In 1625 “Viticos” is marked on de Laet’s map of

Peru as a

mountainous province northeast of Lima and three hundred and fifty

miles

northwest of Vilcabamba! This error was copied by some later

cartographers,

including Mercator, until about 1740, when “Viticos” disappeared from

all maps

of Peru. The map makers had learned that there was no such place in

that

vicinity. Its real location was lost about three hundred years ago. A

map

published at Nuremberg in 1599 gives “Pincos” in the “Andes” mountains,

a small

range west of “Cusco.” This does not seem to have been adopted by other

cartographers; although a Paris map of 1739 gives “Picos” in about the

same

place. Nearly all the cartographers of the eighteenth century who give

“Viticos” supposed it to be the name of a tribe, e.g., “Los Viticos” or

“Les

Viticos.”  PART OF THE NUREMBURG MAP OF 1599, SHOWING PINCOS AND THE ANDES MOUNTAINS The largest official

map of

Peru, the work of that

remarkable explorer, Raimondi, who spent his life crossing and

recrossing Peru,

does not contain the word Uiticos nor any of its numerous spellings,

Viticos,

Vitcos, Pitcos, or Biticos. Incidentally, it may seem strange that

Uiticos

could ever be written “Biticos.” The Quichua language has no sound of

V. The

early Spanish writers, however, wrote the capital letter U exactly like

a

capital V. In official documents and letters Uiticos became Viticos.

The

official readers, who had never heard the word pronounced, naturally

used the V

sound instead of the U sound. Both V and P easily become B. So Uiticos

became

Biticos and Uilcapampa became Vilcabamba. Raimondi’s marvelous

energy led

him to penetrate to

more out-of-the-way Peruvian villages than any one had ever done before

or is

likely to do again, He stopped at nothing in the way of natural

obstacles. In

1865 he went deep into the heart of Uilcapampa; yet found no Uiticos.

He

believed that the ruins of Choqquequirau represented the residence of

the last

Incas. This view had been held by the French explorer, Count de

Sartiges, in

1834, who believed that Choqquequirau was abandoned when Sayri Tupac,

Manco’s

oldest son, went to live in Yucay. Raimondi’s view was also held by the

leading

Peruvian geographers, including Paz Soldan in 1877, and by Prefect

Nunez and

his friends in 1909, at the time of my visit to Choqquequirau.2 The

only

dissenter was the learned Peruvian historian, Don Carlos Romero, who

insisted

that the last Inca capital must be found elsewhere. He urged the

importance of

searching for Uiticos in the valleys of the rivers now called

Vilcabamba and

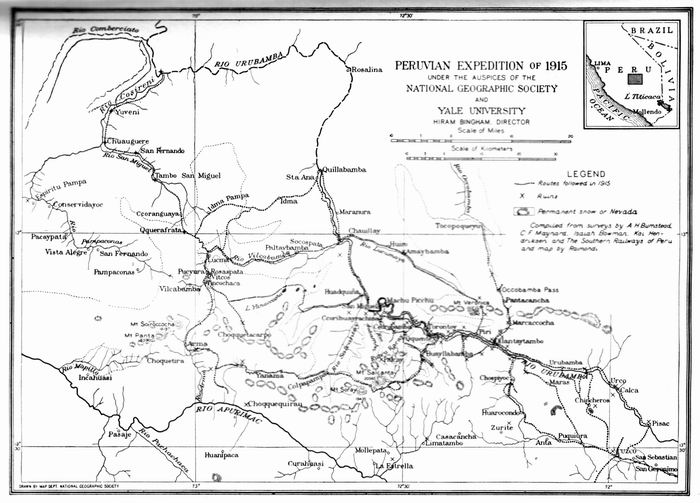

Urubamba. It was to be the work of the Yale Peruvian Expedition of 1911

to

collect the geographical evidence which would meet the requirements of

the

chronicles and establish the whereabouts of the long-lost Inca capital. That there were

undescribed and

unidentified ruins

to be found in the Urubamba Valley was known to a few people in Cuzco,

mostly

wealthy planters who had large estates in the province of Convencion.

One told

us that he went to Santa Ana every year and was acquainted with a

muleteer who

had told him of some interesting ruins near the San Miguel bridge.

Knowing the

propensity of his countrymen to exaggerate, however, he placed little

confidence in the story and, shrugging his shoulders, had crossed the

bridge a

score of times without taking the trouble to look into the matter.

Another,

Seņor Pancorbo, whose plantation was in the Vilcabamba Valley, said

that he had

heard vague rumors of ruins in the valley above his plantation,

particularly

near Pucyura. If his story should prove to be correct, then it was

likely that

this might be the very Puquiura where Friar Marcos had established the

first

church in the “province of Uilcapampa.” But that was “near” Uiticos and

near a

village called Chuquipalpa, where should be found the ruins of a Temple

of the

Sun, and in these ruins a “white rock over a spring of water.” Yet

neither

these friendly planters nor the friends among whom they inquired had

ever heard

of Uiticos or a place called Chuquipalpa, or of such an interesting

rock; nor

had they themselves seen the ruins of which they had heard. One of Seņor

Lomellini’s

friends, a talkative old

fellow who had spent a large part of his life in prospecting for mines

in the

department of Cuzco, said that he had seen ruins “finer than

Choqquequirau” at

a place called Huayna Picchu; but he had never been to Choqquequirau.

Those who

knew him best shrugged their shoulders and did not seem to place much

confidence in his word. Too often he had been over-enthusiastic about

mines

which did not “pan out.” Yet his report resembled that of Charles

Wiener, a

French explorer, who, about 1875, in the course of his wanderings in

the Andes,

visited Ollantaytambo. While there he was told that there were fine

ruins down

the Urubamba Valley at a place called “Huaina-Picchu or Matcho-Picchu.”

He

decided to go down the valley and look for these ruins. According to

his text

he crossed the Pass of Panticalla, descended the Lucumayo River to the

bridge

of Choqquechacca, and visited the lower Urubamba, returning by the same

route.

He published a detailed map of the valley. To one of its peaks he gives

the

name “Huaynapicchu, ele. 1815 m.” and to another “Matchopicchu, ele.

1720 m.”

His interest in Inca ruins was very keen. He devotes pages to

Ollantaytambo. He

failed to reach Machu Picchu or to find any ruins of importance in the

Urubamba

or Vilcabamba valleys. Could we hope to be any more successful? Would

the

rumors that had reached us “pan out” as badly as those to which Wiener

had

listened so eagerly? Since his day, to be sure, the Peruvian Government

had

actually finished a road which led past Machu Picchu. On the other

hand, a

Harvard Anthropological Expedition, under the leadership of Dr. William

C.

Farrabee, had recently been over this road without re-porting any ruins

of

importance. They were looking for savages and not ruins. Nevertheless,

if Machu

Picchu was “finer than Choqquequirau” why had no one pointed it out to

them? To most of our

friends in Cuzco

the idea that there

could be anything finer than Choqquequirau seemed absurd. They regarded

that

“cradle of gold” as “the most remarkable archeological discovery of

recent

times.” They assured us there was nothing half so good. They even

assumed that

we were secretly planning to return thither to dig

for buried treasure! Denials were of no avail. To a people

whose ancestors made fortunes out of lucky “strikes,” and who

themselves have

been brought up on stories of enormous wealth still remaining to be

discovered

by some fortunate excavator, the question of tesoro

— treasure, wealth,

riches — is an ever-present source of conversation. Even the prefect of

Cuzco

was quite unable to conceive of my doing anything for the love of

discovery. He

was convinced that I should find great riches at Choqquequirau — and

that I was

in receipt of a very large salary! He refused to believe that the

members of

the Expedition received no more than their expenses. He told me

confidentially

that Professor Foote would sell his collection of insects for at least

$10,000! Peruvians have not been

accustomed to

see any one do scientific work except as he was paid by the government

or

employed by a railroad or mining company. We have frequently found our

work

misunderstood and regarded with suspicion, even by the Cuzco Historical

Society.  The valley of the

Urubamba, or

Uilcamayu, as it used

to be called, may be reached from Cuzco in several ways. The usual

route for

those going to Yucay is northwest from the city, over the great Andean

highway,

past the slopes of Mt. Sencca. At Ttica-Ttica (12,000 ft.)

the road crosses the lowest pass at the western

end of the

Cuzco Basin. At the last point from which one can see the city of

Cuzco, all

true Indians, whether on their way out of the valley or into it, pause,

turn

toward the east, facing the city, remove their hats and mutter a

prayer. I

believe that the words they use now are those of the “Ave

Maria,” or some other familiar orison of the Catholic

Church.

Nevertheless, the custom undoubtedly goes far back of the advent of the

first

Spanish missionaries. It is probably a relic of the ancient habit of

worshiping

the rising sun. During the centuries immediately preceding the

conquest, the

city of Cuzco was the residence of the Inca himself, that divine

individual who

was at once the head of Church and State. Nothing would have been more

natural

than for persons coming in sight of his residence to perform an act of

veneration. This in turn might have led those leaving the city to fall

into the

same habit at the same point in the road. I have watched hundreds of

travelers

pass this point. None of those whose European costume proclaimed a

white or

mixed ancestry stopped to pray or make obeisance. On the other hand,

all those,

without exception, who were clothed in a native costume, which

betokened that

they considered themselves to be Indians rather than whites, paused for

a

moment, gazing at the ancient city, removed their hats, and said a

short

prayer. Leaving Ttica-Ttica,

we went

northward for several

leagues, passed the town of Chincheros, with its old-Inca walls, and

came at

length to the edge of the wonderful valley of Yucay. In its bottom are

great

level terraces rescued from the Urubamba River by the untiring energy

of the

ancient folk. On both sides of the valley the steep slopes bear many

remains of

narrow terraces, some of which are still in use. Above them are “temporales,” fields of grain, resting

like a patch-work quilt on slopes so steep it seems incredible they

could be

cultivated. Still higher up, their heads above the clouds, are the

jagged

snow-capped peaks. The whole offers a marvelous picture, rich in

contrast,

majestic in proportion. In Yucay once dwelt the Inca Manco’s oldest

son, Sayri

Tupac, after he had accepted the viceroy’s invitation to come under

Spanish

protection. Here he lived three years and here, in 1560, he died an

untimely

death under circumstances which led his brothers, Titu Cusi and Tupac

Amaru, to

think that they would be safer in Uiticos. We spent the night in

Urubamba, the

modern capital of the province, much favored by Peruvians of to-day

because of

its abundant water supply, delightful climate, and rich fruits. Cuzco,

11,000

feet, is too high to have charming surroundings, but two thousand feet

lower,

in the Urubamba Valley, there is everything to please the eye and

delight the

horticulturist. Speaking of

horticulturists

reminds me of their

enemies. Uru is the Quichua word for

caterpillars or grubs, pampa means flat land. Urubamba is “flat-land-where-there-are-grubs-or-caterpillars.”

Had it been named by people who came up from a warm region where

insects

abound, it would hardly have been so denominated. Only people not

accustomed to

land where caterpillars and grubs flourished would have been struck by

such a

circumstance. Consequently, the valley was probably named by plateau

dwellers

who were working their way down into a warm region where butterflies

and moths

are more common. Notwithstanding its celebrated cater-pillars,

Urubamba’s

gardens of to-day are full of roses, lilies, and other brilliant

flowers. There

are orchards of peaches, pears, and apples; there are fields where

luscious

strawberries are raised for the Cuzco market. Apparently, the grubs do

not get

everything. The next day down the

valley

brought us to romantic

Ollantaytambo, described in glowing terms by Castelnau, Marcou, Wiener,

and

Squier many years ago. It has lost none of its charm, even though

Marcou’s

drawings are imaginary and Squier’s are exaggerated. Here, as at

Urubamba,

there are flower gardens and highly cultivated green fields. The brooks

are

shaded by willows and poplars. Above them are magnificent precipices

crowned by

snow-capped peaks. The village itself was once the capital of an

ancient

principality whose history is shrouded in mystery. There are ruins of.

curious

gabled buildings, storehouses, “prisons,” or “monasteries,” perched

here and

there on well-nigh inaccessible crags above the village. Below are

broad

terraces of unbelievable extent where abundant crops are still

harvested;

terraces which will stand for ages to come as monuments to the energy

and skill

of a bygone race. The “fortress” is on a little hill, surrounded by

steep

cliffs, high walls, and hanging gardens so as to be difficult of

access.

Centuries ago, when the tribe which cultivated the rich fields in this

valley

lived in fear and terror of their savage neighbors, this hill offered a

place

of refuge to which they could retire. It may have been fortified at

that time.

As centuries passed in which the land came under the control of the

Incas,

whose chief interest was the peaceful promotion of agriculture, it is

likely

that this fortress became a royal garden. The six great ashlars of

reddish

granite weighing fifteen or twenty tons each, and placed in line on the

summit

of the hill, were brought from a quarry several miles away with an

immense

amount of labor and pains. They were probably intended to be a record

of the

magnificence of an able ruler. Not only could he command the services

of a

sufficient number of men to extract these rocks from the quarry and

carry them

up an inclined plane from the bottom of the valley to the summit of the

hill;

he had to supply the men with food. The building of such a monument

meant

taking five hundred Indians away from their ordinary occupations as

agriculturists. He must have been a very good administrator. To his

people the

magnificent megaliths were doubtless a source of pride. To his enemies

they

were a symbol of his power and might.  MT. VERONICA AND SALAPUNCO, THE GATEWAY TO UILCAPAMPA A league below

Ollantaytambo

the road forks. The

right branch ascends a steep valley and crosses the pass of Panticalla

near

snow-covered Mt. Veronica. Near the pass are two groups of ruins. One

of them,

extravagantly referred to by Wiener as a “granite palace, whose

appearance [appareil] resembles the

more beautiful

parts of Ollantaytambo,” was only a storehouse. The other was probably

a tampu,

or inn, for the benefit of official travelers. All travelers in Inca

times,

even the bearers of burdens, were acting under official orders.

Commercial

business was unknown. The rights of personal property were not

understood. No

one had anything to sell; no one had any money to buy it with. On the

other

hand, the Incas had an elaborate system of tax collecting. Two thirds

of the

produce raised by their subjects was claimed by the civil and religious

rulers.

It was a reasonable provision of the benevolent despotism of the Incas

that

inhospitable regions like the Panticalla Pass near Mt. Veronica should

be

provided with suitable rest houses and storehouses. Polo de Ondegardo,

an able

and accomplished statesman, who was in office in Cuzco in 1560, says

that the

food of the chasquis, Inca post

runners, was provided from official storehouses; “those who worked for

the

Inca’s service, or for religion, never ate at their own expense.” In

Manco’s

day these buildings at Havaspampa probably sheltered the outpost which

defeated

Captain Villadiego. Before the completion

of the

river road, about 1895,

travelers from Cuzco to the lower Urubamba had a choice of two routes,

one by

way of the pass of Panticalla, followed by Captain Garcia in 1571, by

General

Miller in 1835, Castelnau in 1842, and Wiener in 1875; and one by way

of the

pass between Mts. Salcantay and Soray, along the Salcantay River to

Huadquina,

followed by the Count de Sartiges in 1834 and Raimondi in 1865. Both of

these

routes avoid the highlands between Mt. Salcantay and Mt. Veronica and

the

lowlands between the villages of Piri and Huadquina. This region was in

1911

undescribed in the geographical literature of southern Peru. We decided

not to

use either pass, but to go straight down the Urubamba river road. It

led us

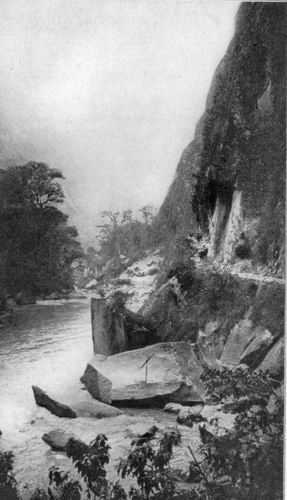

into a fascinating country. Two leagues beyond

Piri, at

Salapunco, the road

skirts the base of precipitous cliffs, the beginnings of a wonderful

mass of

granite mountains which have made Uilcapampa more difficult of access

than the

surrounding highlands which are composed of schists, conglomerates, and

limestone. Salapunco is the natural gateway to the ancient province,

but it was

closed for centuries by the combined efforts of nature and man. The

Urubamba

River, in cutting its way through the granite range, forms rapids too

dangerous

to be passable and precipices which can be scaled only with great

effort and

considerable peril. At one time a footpath probably ran near the river,

where

the Indians, by crawling along the face of the cliff and sometimes

swinging

from one ledge to another on hanging vines, were able to make their way

to any

of the alluvial terraces down the valley. Another path may have gone

over the

cliffs above the fortress, where we noticed, in various inaccessible

places,

the remains of walls built on narrow ledges. They were too narrow and

too

irregular to have been intended to support agricultural terraces. They

may have

been built to make the cliff more precipitous. They probably represent

the

foundations of an old trail. To defend these ancient paths we found

that

prehistoric man had built, at the foot of the precipices, close to the

river, a

small but powerful fortress whose ruins now pass by the name of

Salapunco; sala

= ruins; punco = gateway. Fashioned after famous

Sacsahuaman and

resembling it in the irregular character of the large ashlars and also

by

reason of the salients and reentrant angles which enabled its defenders

to

prevent the walls being successfully scaled, it presents an interesting

problem. Commanding as it does

the

entrance to the valley of

Torontoy, Salapunco may have been built by some ancient chief to enable

him to

levy tribute on all who passed. My first impression was that the

fortress was

placed here, at the end of the temperate zone, to defend the valleys of

Urubamba and Ollantaytambo against savage enemies coming up from the

forests of

the Amazon. On the other hand, it is possible that Salapunco was built

by the

tribes occupying the fastnesses of Uilcapampa as an outpost to defend

them

against enemies coming down the valley from the direction of

Ollantaytambo.

They could easily have held it against a considerable force, for it is

powerfully built and constructed with skill. Supplies from the

plantations of

Torontoy, lower down the river, might have reached it along the path

which

antedated the present government road. Salapunco may have been occupied

by the

troops of the Inca Manco when he established himself in Uiticos and

ruled over

Uilcapampa. He could hardly, however, have built a megalithic work of

this

kind. It is more likely that he would have destroyed the narrow trails

than

have attempted to hold the fort against the soldiers of Pizarro.

Furthermore,

its style and character seem to date it with the well-known megalithic

structures of Cuzco and Ollantaytambo. This makes it seem all the more

extraordinary that Salapunco could ever have been built as a defense

against

Ollantaytambo, unless it was built by folk who once occupied Cuzco and

who

later found a retreat in the canyons below here.  GROSVENOR GLACIER AND MT. SALCANTAY When we first visited

Salapunco

no megalithic

remains had been reported as far down the valley as this. It never

occurred to

us that, in hunting for the remains of such comparatively recent

structures as

the Inca Manco had the force and time to build, we were to discover

remains of

a far more remote past. Yet we were soon to find ruins enough to

explain why

such a fortress as Salapunco might possibly have been built so as to

defend

Uilcapampa against Ollantaytambo and Cuzco and not those well-known

Inca cities

against the savages of the Amazon jungles. Passing Salapunco, we

skirted

granite cliffs and

precipices and entered a most interesting region, where we were

surprised and

charmed by the extent of the ancient terraces, their length and height,

the

presence of many Inca ruins, the beauty of the deep, narrow valleys,

and the

grandeur of the snow-clad mountains which towered above them. Across

the river,

near Qquente, on top of a series of terraces, we saw the extensive

ruins of

Patallacta (pata = height or terrace; llacta

= town or city), an

Inca town of great importance. It was not known to Raimondi or Paz

Soldan, but

is indicated on Wiener’s map, although he does not appear to have

visited it.

We have been unable to find any reference to it in the chronicles. We

spent

several months here in 1915 excavating and determining the character of

the

ruins. In another volume I hope to tell more of the antiquities of this

region.

At present it must suffice to remark that our explorations near

Patallacta

disclosed no “white rock over a spring of water.” None of the place

names in

this vicinity fit in with the accounts of Uiticos. Their identity

remains a

puzzle, although the symmetry of the buildings, their architectural

idiosyncrasies such as niches, stone roof-pegs, bar-holds, and

eye-bonders,

indicate an Inca origin. At what date these towns and villages

flourished, who

built them, why they were deserted, we do not yet know; and the Indians

who

live hereabouts are ignorant, or silent, as to their history. At

Torontoy, the

end of the cultivated temperate valley, we found another group of

interesting

ruins, possibly once the residence of an Inca chief. In a cave near by

we

secured some mummies. The ancient wrappings had been consumed by the

natives in

an effort to smoke out the vampire bats that lived in the cave. On the

opposite

side of the river are extensive terraces and above them, on a hilltop,

other

ruins first visited by Messrs. Tucker and Hendriksen in 1911. One of

their

Indian bearers, attempting to ford the rapids here with a large

surveying

instrument, was carried off his feet, swept away by the strong current,

and

drowned before help could reach him. Near Torontoy is a

densely

wooded valley called the

Pampa Ccahua. In 1915 rumors of Andean or “spectacled” bears having

been seen

here and of damage having been done by them to some of the higher

crops, led us

to go and investigate. We found no bears, but at an elevation of 12,000

feet

were some very old trees, heavily covered with flowering moss not

hitherto known

to science. Above them I was so fortunate as to find a wild potato

plant, the

source from which the early Peruvians first developed many varieties of

what we

incorrectly call the Irish potato. The tubers were as large as peas. Mr. Heller found here

a strange

little cousin of the

kangaroo, a near relative of the coenolestes. It

turned out to be new to

science. To find a new genus of mammalian quadrupeds was an event which

delighted Mr. Heller far more than shooting a dozen bears.3 Torontoy is at the

beginning of

the Grand Canyon of

the Urubamba, and such a canyon! The river “road” runs recklessly up

and down

rock stairways, blasts its way beneath overhanging precipices, spans

chasms on

frail bridges propped on rustic brackets against granite cliffs. Under

dense

forests, wherever the encroaching precipices permitted it, the land

between

them and the river was once terraced and cultivated. We found ourselves

unexpectedly in a veritable wonderland. Emotions came thick and fast.

We

marveled at the exquisite pains with which the ancient folk had rescued

incredibly narrow strips of arable land from the tumbling rapids. How

could

they ever have managed to build a retaining wall of heavy stones along

the very

edge of the dangerous river, which it is death to attempt to cross! On

one

sightly bend near a foaming waterfall some Inca chief built a temple,

whose

walls tantalize the traveler. He must pass by within pistol shot of the

interesting ruins, unable to ford the intervening rapids. High up on

the side

of the canyon, five thousand feet above this temple, are the ruins of

Corihuayrachina (kori = “gold”; huayaya = “wind”; huayrachina = “a

threshing-floor where winnowing takes place.” Possibly this was an

ancient gold

mine of the Incas. Half a mile above us on another steep slope, some

modern

pioneer had recently cleared the jungle from a fine series of ancient

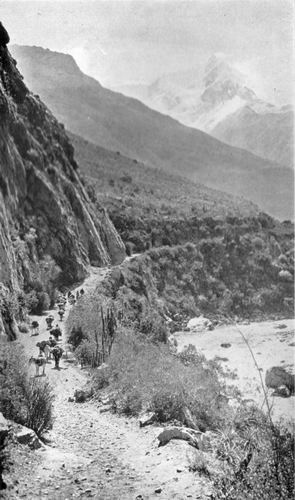

artificial terraces. On the afternoon of

July 23d we

reached a hut called “La Maquina,” where travelers

frequently stop for the night. The name comes from the presence here of

some

large iron wheels, parts of a “machine” destined never to overcome the

difficulties of being transported all the way to a sugar estate in the

lower

valley, and years ago left here to rust in the jungle. There was little

fodder,

and there was no good place for us to pitch our camp, so we pushed on

over the

very difficult road, which had been carved out of the face of a great

granite

cliff. Part of the cliff had slid off into the river and the breach

thus made

in the road had been repaired by means of a frail-looking rustic bridge

built

on a bracket composed of rough logs, branches, and reeds, tied together

and

surmounted by a few inches of earth and pebbles to make it seem

sufficiently

safe to the cautious cargo mules who picked their way gingerly across

it. No

wonder “the machine” rested where it did and gave its name to that part

of the

valley.  THE ROAD BETWEEN MAQUINA AND MANDOR PAMPA NEAR MACHU PICCHU Dusk falls early in

this deep

canyon, the sides of

which are considerably over a mile in height. It was almost dark when

we passed

a little sandy plain two or three acres in extent, which in this land

of steep

mountains is called a pampa. Were

the

dwellers on the pampas of

Argentina —

where a railroad can go for 250 miles in a straight line, except for

the

curvature of the earth — to see this little bit of flood-plain called

Mandor

Pampa, they would think some one had been joking or else grossly

misusing a

word which means to them illimitable space with not a hill in sight.

However,

to the ancient dwellers in this valley, where level land was so scarce

that it

was worth while to build high stone-faced terraces so as to enable two

rows of

corn to grow where none grew before, any little natural breathing space

in the

bottom of the canyon is called a pampa. We passed an

ill-kept,

grass-thatched hut, turned

off the road through a tiny clearing, and made our camp at the edge of

the

river Urubamba on a sandy beach. Opposite us, beyond the huge granite

boulders

which interfered with the progress of the surging stream, was a steep

mountain

clothed with thick jungle. It was an ideal spot for a camp, near the

road and

yet secluded. Our actions, however, aroused the suspicions of the owner

of the

hut, Melchor Arteaga, who leases the lands of Mandor Pampa. He was

anxious to

know why we did not stay at his hut like respectable travelers. Our gendarme, Sergeant Carrasco, reassured

him. They had quite a long conversation. When Arteaga learned that we

were

interested in the architectural remains of the Incas, he said there

were some

very good ruins in this vicinity — in fact, some excellent ones on top

of the

opposite mountain, called Huayna Picchu, and also on a ridge called

Machu

Picchu. These were the very places Charles Wiener heard of at

Ollantaytambo in

1875 and had been unable to reach. The story of my experiences on the

following

day will be found in a later chapter. Suffice it to say at this point

that the

ruins of Huayna Picchu turned out to be of very little importance,

while those

of Machu Picchu, familiar to readers of the “National Geographic

Magazine,” are

as interesting as any ever found in the Andes. When I first saw the

remarkable

citadel of Machu

Picchu perched on a narrow ridge two thousand feet above the river, I

wondered

if it could be the place to which that old soldier, Baltasar de Ocampo,

a

member of Captain Garcia’s expedition, was referring when he said: “The

Inca

Tupac Amaru was there in the fortress of Pitcos [Uiticos], which is on

a very

high mountain, whence the view commanded a great part of the province

of

Uilcapampa. Here there was an extensive level space, with very

sumptuous and

majestic buildings, erected with great skill and art, all the lintels

of the

doors, the principal as well as the ordinary ones, being of marble,

elaborately

carved.” Could it be that “Picchu” was the modern variant of “Pitcos”?

To be

sure, the white granite of which the temples and palaces of Machu

Picchu are

constructed might easily pass for marble. The difficulty about fitting

Ocampo’s

description to Machu Picchu, however, was that there was no difference

between the

lintels of the doors and the walls themselves. Furthermore, there is no

“white

rock over a spring of water” which Calancha says was “near Uiticos.”

There is

no Pucyura in this neighborhood. In fact, the canyon of the Urubamba

does not

satisfy the geographical requirements of Uiticos. Although containing

ruins of

surpassing interest, Machu Picchu did not represent that last Inca

capital for

which we were searching. We had not yet found Manco’s palace. ___________________________

1 Uiticos is probably derived from Uiticuni, meaning “to withdraw to a distance.” 2

Described in “Across South America.” 3 On

the 1915 Expedition Mr. Heller captured twelve new species of mammals,

but, as

Mr. Oldfield Thomas says: “Of all the novelties, by far the most

interesting is

the new Marsupial.... Members of the family were previously known from

Colombia

and Ecuador.” Mr. Heller’s discovery greatly extends the recent range

of the

kangaroo family. |