|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XII THE FORTRESS OF UITICOS AND THE HOUSE OF THE SUN WHEN the viceroy,

Toledo,

determined to conquer that

last stronghold of the Incas where for thirty-five years they had

defied the

supreme power of Spain, he offered a thousand dollars a year as a

pension to

the soldier who would capture Tupac Amaru. Captain Garcia earned the

pension,

but failed to receive it; the “maņana habit” was already strong in the

days of

Philip II. So the doughty captain filed a collection of testimonials

with

Philip’s Royal Council of the Indies. Among these is his own statement

of what

happened on the campaign against Tupac Amaru. In this he says: “and

having

arrived at the principal fortress, Guaynapucara [“the young fortress”],

which

the Incas had fortified, we found it defended by the Prince Philipe

Quispetutio, a son of the Inca Titu Cusi, with his captains and

soldiers. It is

on a high eminence surrounded with rugged crags and jungles, very

dangerous to

ascend and almost impregnable. Nevertheless, with my aforesaid company

of

soldiers I went up and gained the fortress, but only with the greatest

possible

labor and danger. Thus we gained the province of Uilcapampa.” The

viceroy

himself says this important victory was due to Captain Garcia’s skill

and

courage in storming the heights of Guaynapucara, “on Saint John the

Baptist’s

day, in 1572.” The “Hill of Roses”

is indeed

“a high eminence

surrounded with rugged crags.” The side of easiest approach is

protected by a

splendid, long wall, built so carefully as not to leave a single

toe-hold for

active besiegers. The barracks at Uncapampa could have furnished a

contingent

to make an attack on that side very dangerous. The hill is steep on all

sides,

and it would have been extremely easy for a small force to have

defended it. It

was undoubtedly “almost impregnable.” This was the feature Captain

Garcia was

most likely to remember. On the very summit of the hill are the ruins of a partly enclosed compound consisting of thirteen or fourteen houses arranged so as to form a rough square, with one large and several small courtyards. The outside dimensions of the compound are about 160 feet by 145 feet. The builders showed the familiar Inca sense of symmetry in arranging the houses. Due to the wanton destruction of many buildings by the natives in their efforts at treasure-hunting, the walls have been so pulled down that it is impossible to get the exact dimensions of the buildings. In only one of them could we be sure that there had been any niches.

Most interesting of

all is the

structure which

caught the attention of Ocampo and remained fixed in his memory. Enough

remains

of this building to give a good idea of its former grandeur. It was

indeed a

fit residence for a royal Inca, an exile from Cuzco. It is 245 feet by

43 feet.

There were no windows, but it was lighted by thirty doorways, fifteen

in front

and the same in back. It contained ten large rooms, besides three

hallways

running from front to rear. The walls were built rather hastily and are

not

noteworthy, but the principal entrances, namely, those leading to each

hall,

are particularly well made; not, to be sure, of “marble” as Ocampo said

— there

is no marble in the province — but of finely cut ashlars of white

granite. The

lintels of the principal doorways, as well as of the ordinary ones, are

also of

solid blocks of white granite, the largest being as much as eight feet

in

length. The doorways are better than any other ruins in Uilcapampa

except those

of Machu Picchu, thus justifying the mention of them made by Ocampo,

who lived

near here and had time to become thoroughly familiar with their

appearance.

Unfortunately, a very small portion of the edifice was still standing.

Most of

the rear doors had been filled up with ashlars, in order to make a

continuous

fence. Other walls had been built from the ruins, to keep cattle out of

the

cultivated pampa. Rosaspata is at an elevation which

places it on the

borderland between the cold grazing country, with its root crops and

sublimated

pigweeds, and the temperate zone where maize flourishes. On the south side of

the

hilltop, opposite the long

palace, is the ruin of a single structure, 78 feet long and 35 feet

wide,

containing doors on both sides, no niches and no evidence of careful

workmanship.

It was probably a barracks for a company of soldiers. The intervening

“pampa” might

have been the scene of

those games of bowls and quoits, which were played by the Spanish

refugees who

fled from the wrath of Gonzalo Pizarro and found refuge with the Inca

Manco.

Here may have occurred that fatal game when one of the players lost his

temper

and killed his royal host. Our excavations in

1915 yielded

a mass of rough

potsherds, a few Inca whirl-bobs and bronze shawl pins, and also a

number of

iron articles of European origin, heavily rusted — horseshoe nails, a

buckle, a

pair of scissors, several bridle or saddle ornaments, and three

Jew’s-harps. My

first thought was that modern Peruvians must have lived here at one

time,

although the necessity of carrying all water supplies up the hill would

make

this unlikely. Furthermore, the presence here of artifacts of European

origin

does not of itself point to such a conclusion. In the first place, we

know that

Manco was accustomed to make raids on Spanish travelers between Cuzco

and Lima.

He might very easily have brought back with him a Spanish bridle. In

the second

place the musical instruments may have belonged to the refugees, who

might have

enjoyed whiling away their exile with melancholy twanging. In the third

place

the retainers of the Inca probably visited the Spanish market in Cuzco,

where

there would have been displayed at times a considerable assortment of

goods of

European manufacture. Finally Rodriguez de Figueroa speaks expressly of

two

pairs of scissors he brought as a present to Titu Cusi. That no such

array of

European artifacts has been turned up in the excavations of other

important

sites in the province of Uilcapampa would seem to indicate that they

were

abandoned before the Spanish Conquest or else were occupied by natives

who had

no means of accumulating such treasures. Thanks to Ocampo’s

description

of the fortress which

Tupac Amaru was occupying in 1572 there is no doubt that this was the

palace of

the last Inca. Was it also the capital of his brothers, Titu Cusi and

Sayri

Tupac, and his father, Manco? It is astonishing how few details we have

by

which the Uiticos of Manco may be identified. His contemporaries are

strangely

silent. When he left Cuzco and sought refuge “in the remote fastnesses

of the

Andes,” there was a Spanish soldier, Cieza de Leon, in the armies of

Pizarro

who had a genius for seeing and hearing interesting things and writing

them

down, and who tried to interview as many members of the royal family as

he

could; — Manco had thirteen brothers. Cieza de Leon says he was much

disappointed not to be able to talk with Manco himself and his sons,

but they

had “retired into the provinces of Uiticos, which are in the most

retired part

of those regions, beyond the great Cordillera of the Andes.”1

The

Spanish refugees who died as the result of the murder of Manco may not

have

known how to write. Anyhow, so far as we can learn they left no

accounts from

which any one could identify his residence. Titu Cusi gives no

definite clue, but the activities of Friar Marcos and Friar Diego, who

came to

be his spiritual advisers, are fully described by Calancha. It will be

remembered that Calancha remarks that “close to Uiticos in a village

called

Chuquipalpa, is a House of the Sun and in it a white stone over a

spring of

water.” Our guide had told us there was such a place close to the hill

of

Rosaspata.  NORTHEAST FACE OF YURAK RUMI On the day after

making the

first studies of the

“Hill of Roses,” I followed the impatient Mogrovejo — whose object was

not to

study ruins but to earn dollars for finding them — and went over the.

hill on

its northeast side to the Valley of Los Andenes (“the

Terraces”). Here, sure enough, was a large, white granite boulder,

flattened on

top, which had a carved seat or platform on its northern side. Its west

side

covered a cave in which were several niches. This cave had been walled

in on

one side. When Mogrovejo and the Indian guide said there was a manantial de agua (“spring of water”)

near by, I became greatly interested. On investigation, however, the

“spring”

turned out to be nothing but part of a small irrigating ditch. (Manantial means “spring”; it also means

“running water”). But the rock was not “over the water.” Although this

was

undoubtedly one of those huacas, or sacred

boulders, selected by the Incas as the visible representations of the

founders

of a tribe and thus was an important accessory to ancestor worship, it

was not

the Yurak Rumi for which we were looking. Leaving the boulder and the

ruins of

what possibly had been the house of its attendant priest, we followed

the

little water course past a large number of very handsomely built

agricultural

terraces, the first we had seen since leaving Machu Picchu and the most

important ones in the valley. So scarce are andenes

in this region and so noteworthy were these in

particular that this vale

has been named after them. They were probably built under the direction

of

Manco. Near them are a number of carved boulders, huacas.

One had an intihuatana,

or sundial nubbin, on it; another was carved in the

shape of a saddle.

Continuing, we followed a trickling stream through thick woods until we

suddenly arrived at an open place called Nusta Isppana. Here before us

was a

great white rock over a spring. Our guides had not misled us. Beneath

the trees

were the ruins of an Inca temple, flanking and partly enclosing the

gigantic

granite boulder, one end of which overhung a small pool of running

water. When

we learned that the present name of this immediate vicinity is

Chuquipalta our

happiness was complete. It was late on the

afternoon of

August 9, 1911, when

I first saw this remarkable shrine. Densely wooded hills rose on every

side.

There was not a hut to be seen; scarcely a sound to be heard. It was an

ideal

place for practicing the mystic ceremonies of an ancient cult. The

remarkable

aspect of this great boulder and the dark pool beneath its shadow had

caused

this to become a place of worship. Here, without doubt, was “the

principal mochadero of those

forested mountains.”

It is still venerated by the Indians of the vicinity. At last we had

found the

place where, in the days of Titu Cusi, the Inca priests faced the east,

greeted

the rising sun, “extended their hands toward it,” and “threw kisses to

it,” “a

ceremony of the most profound resignation and reverence.” We may

imagine the

sun priests, clad in their resplendent robes of office, standing on the

top of

the rock at the edge of its steepest side, their faces lit up with the

rosy

light of the early morning, awaiting the moment when the Great Divinity

should appear

above the eastern hills and receive their adoration. As it rose they

saluted it

and cried: “O Sun! Thou who art in peace and safety, shine upon us,

keep us

from sickness, and keep us in health and safety. O Sun! Thou who hast

said let

there be Cuzco and Tampu, grant that these children may conquer all

other

people. We beseech thee that thy children the Incas may be always

conquerors,

since it is for this that thou hast created them.” It was during Titu

Cusi’s reign

that Friars Marcos

and Diego marched over here with their converts from Puquiura, each

carrying a

stick of firewood. Calancha says the Indians worshiped the water as a

divine

thing, that the Devil had at times shown himself in the water. Since

the

surface of the little pool, as one gazes at it, does not reflect the

sky, but

only the overhanging, dark, mossy rock, the water looks black and

forbidding,

even to unsuperstitious Yankees. It is easy to believe that

simple-minded

Indian worshipers in this secluded spot could readily believe that they

actually saw the Devil appearing “as a visible manifestation” in the

water.

Indians came from the most sequestered villages of the dense forests to

worship

here and to offer gifts and sacrifices. Nevertheless, the Augustinian

monks

here raised the standard of the cross, recited their orisons, and piled

firewood all about the rock and temple. Exorcising the Devil and

calling him by

all the vile names they could think of, the friars commanded him never

to

return. Setting fire to the pile, they burned up the temple, scorched

the rock,

making a powerful impression on the Indians and causing the poor Devil

to flee,

“roaring in a fury.” “The cruel Devil never more returned to the rock

nor to

this district.” Whether the roaring which they heard was that of the

Devil or

of the flames we can only conjecture. Whether the conflagration

temporarily

dried up the swamp or interfered with the arrangements of the water

supply so

that the pool disappeared for the time being and gave the Devil no

chance to

appear in the water, where he had formerly been accustomed to show

himself, is

also a matter for speculation. The buildings of the

House of

the Sun are in a very

ruinous state, but the rock itself, with its curious carvings, is well

preserved notwithstanding the great conflagration of 1570. Its length

is

fifty-two feet, its width thirty feet, and its height above the present

level

of the water, twenty-five feet. On the west side of the rock are seats

and

large steps or platforms. It was customary to kill llamas at these holy huacas. On top of the rock is a

flattened place which may have been used for such sacrifices. From it

runs a

little crack in the boulder, which has been artificially enlarged and

may have

been intended to carry off the blood of the victim killed on top of the

rock.

It is still used for occult ceremonies of obscure origin which are

quietly

practiced here by the more superstitious Indian women of the valley,

possibly

in memory of the Nusta or Inca princess for whom the shrine is named. On the south side of

the

monolith are several large

platforms and four or five small seats which have been cut in the rock.

Great

care was exercised in cutting out the platforms. The edges are very

nearly

square, level, and straight. The east side of the rock projects over

the spring.

Two seats have been carved immediately above the water. On the north

side there

are no seats. Near the water, steps have been carved. There is one

flight of

three and another of seven steps. Above them the rock has been

flattened

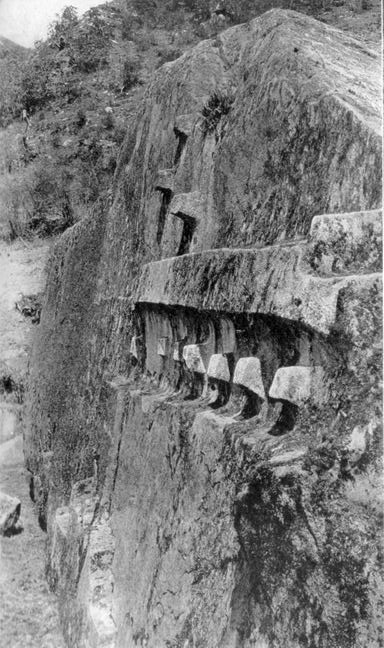

artificially and carved into a very bold relief. There are ten

projecting

square stones, like those usually called intihuatana

or “places to which the sun is tied.” In one line are

seven; one is

slightly apart from the six others. The other three are arranged in a

triangular position above the seven. It is significant that these

stones are on

the northeast face of the rock, where they are exposed to the rising

sun and

cause striking shadows at sunrise.

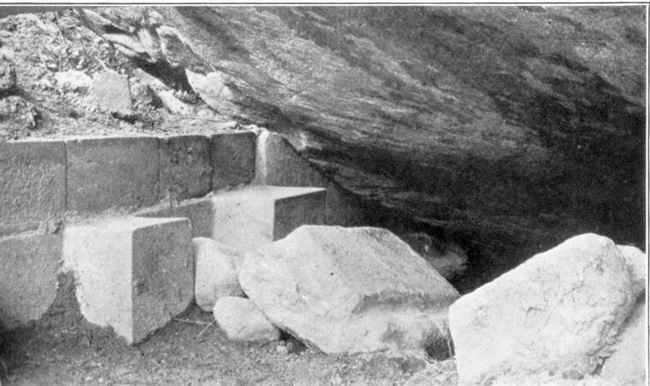

TWO OF THE SEVEN SEATS NEAR THE SPRING UNDER THE GREAT WHITE ROCK Our excavations

yielded no

artifacts whatever and

only a handful of very rough old potsherds of uncertain origin. The

running

water under the rock was clear and appeared to be a spring, but when we

drained

the swamp which adjoins the great rock on its northeastern side, we

found that

the spring was a little higher up the hill and that the water ran

through the

dark pool. We also found that what looked like a stone culvert on the

borders

of the little pool proved to be the top of the back of a row of seven

or eight

very fine stone seats. The platform on which the seats rested and the

seats

themselves are parts of three or four large rocks nicely fitted

together. Some

of the seats are under the black shadows of the overhanging rock. Since

the

pool was an object of fear and mystery the seats were probably used

only by

priests or sorcerers. It would have been a splendid place to practice

divination. No doubt the devils “roared.” All our expeditions

in the

ancient province of

Uilcapampa have failed to disclose the presence of any other “white

rock over a

spring of water” surrounded by the ruins of a possible “House of the

Sun.”

Consequently it seems reasonable to adopt the following conclusions: First,

Nusta Isppana is the Yurak Rumi of Father Calancha. The Chuquipalta of

to-day

is the place to which he refers as Chuquipalpa. Second,

Uiticos, “close to” this shrine, was once the name of

the

present valley of Vilcabamba between Tincochaca and Lucma. This is the

“Viticos” of Cieza de Leon, a contemporary of Manco, who says that it

was to

the province of Viticos that Manco determined to retire when he

rebelled

against Pizarro, and that “having reached Viticos with a great quantity

of

treasure collected from various parts, together with his women and

retinue, the

king, Manco Inca, established himself in the strongest place he could

find, whence

he sallied forth many times and in many directions and disturbed those

parts

which were quiet, to do what harm he could to the Spaniards, whom he

considered

as cruel enemies.” Third, the

“strongest place” of Cieza, the Guaynapucara of Garcia, was Rosaspata,

referred

to by Ocampo as “the fortress of Pitcos,” where, he says, “there was a

level

space with majestic buildings,” the most noteworthy feature of which

was that

they had two kinds of doors and both kinds had white stone lintels. Fourth, the modern village of Pucyura in

the valley of the river Vilcabamba is the Puquiura of Father Calancha,

the site

of the first mission church in this region, as assumed by Raimondi,

although he

was disappointed in the insignificance of the “wretched little

village.” The

remains of the old quartz-crushing plant in Tincochaca, which has

already been

noted, the distance from the “House of the Sun,” not too great for the

religious procession, and the location of Pucyura near the fortress,

all point

to the correctness of this conclusion. Finally, Calancha

says that

Friar Ortiz, after he

had secured permission from Titu Cusi to establish the second

missionary

station in Uilcapampa, selected “the town of Huarancalla, which was

populous

and well located in the midst of a number of other little towns and

villages.

There was a distance of two or three days’ journey from one convent to

the

other. Leaving Friar Marcos in Puquiura, Friar Diego went to his new

establishment, and in a short dine built a church.” There is no

“Huarancalla”

to-day, nor any tradition of any, but in Mapillo, a pleasant valley at

an

elevation of about 10,000 feet, in the temperate zone where the crops

with

which the Incas were familiar might have been raised, near pastures

where

llamas and alpacas could have flourished, is a place called

Huarancalque The

valley is populous and contains a number of little towns and villages.

Furthermore, Huarancalque is two or three days’ journey from Pucyura

and is on

the road which the Indians of this region now use in going to Ayacucho.

This

was undoubtedly the route used by Manco in his raids on Spanish

caravans. The

Mapillo flows into the Apurimac near the mouth of the river Pampas. Not

far up

the Pampas is the important bridge between Bombon and Ocros, which Mr.

Hay and

I crossed in 1909 on our way from Cuzco to Lima. The city of Ayacucho

was

founded by Pizarro, a day’s journey from this bridge. The necessity for

the

Spanish caravans to cross the river Pampas at this point made it easy

for

Manco’s foraging expeditions to reach them by sudden marches from

Uiticos down

the Mapillo River by way of Huarancalque, which is probably the

“Huarancalla”

of Calancha’s “Chronicles.” He must have had rafts or canoes on which

to cross

the Apurimac, which is here very wide and deep. In the valleys between

Huarancalque and Lucma, Manco was cut off from central Peru by the

Apurimac and

its magnificent canyon, which in many places has a depth of over two

miles. He

was cut off from Cuzco by the inhospitable snow fields and glaciers of

Salcantay,

Soray, and the adjacent ridges, even though they are only fifty miles

from

Cuzco. Frequently all the passes are completely snow-blocked.

Fatalities have

been known even in recent years. In this mountainous province Manco

could be

sure of finding not only security from his Spanish enemies, but any

climate

that he desired and an abundance of food for his followers. There seems

to be

no reason to doubt that the retired region around the modern town of

Pucyura in

the upper Vilcabamba Valley was once called Uiticos. __________________

1 In

those days the term “Andes” appears to have been very limited in scope,

and was

applied only to the high range north of Cuzco where lived the tribe

called

Antis. Their name was given to the range. Its culminating point was Mt.

Salcantay. |