|

CHAPTER

IX

THE

LAST FOUR INCAS

READERS of Prescott’s

charming

classic, “The Conquest of Peru,” will

remember that Pizarro, after killing Atahualpa, the Inca who had tried

in vain

to avoid his fate by filling a room with vessels of gold, decided to

establish

a native prince on the throne of the Incas to rule in accordance with

the

dictates of Spain. The young prince, Manco, a son of the great Inca

Huayna

Capac, named for the first Inca, Manco Ccapac, the founder of the

dynasty, was

selected as the most acceptable figurehead. He was a young man of

ability and

spirit. His induction into office in 1534 with appropriate ceremonies,

the

barbaric splendor of which only made the farce the more pitiful, did

little to

gratify his natural ambition. As might have been foreseen, he chafed

under

restraint, escaped as soon as possible from his attentive guardians,

and raised

an army of faithful Quichuas. There followed the siege of Cuzco,

briefly

characterized by Don Alonzo Enriques de Guzman, who took part in it, as

“the

most fearful and cruel war in the world.” When in 1536 Cuzco was

relieved by

Pizarro’s comrade, Almagro, and Manco’s last chance of regaining the

ancient

capital of his ancestors failed, the Inca retreated to Ollantaytambo.

Here, on

the banks of the river Urubamba, Manco made a determined stand, but

Ollantaytambo was too easily reached by Pizarro’s mounted cavaliers.

The Inca’s

followers, although aroused to their utmost endeavors by the presence

of the

magnificent stone edifices, fortresses, granaries, palaces, and hanging

gardens

of their ancestors, found it necessary to retreat. They fled in a

northerly

direction and made good their escape over snowy passes to Uiticos in

the

fastnesses of Uilcapampa, a veritable American Switzerland.

GLACIERS BETWEEN CUZCO AND UITICOS The Spaniards who

attempted to follow Manco found his

position

practically impregnable. The citadel of Uilcapampa, a gigantic natural

fortress

defended by Nature in one of her profoundest moods, was only to be

reached by

fording dangerous torrents, or crossing the mountains by narrow defiles

which

themselves are higher than the most lofty peaks of Europe. It was

hazardous for

Hannabal and Napoleon to bring their armies through the comparatively

low

passes of the Alps. Pizarro

found it

impossible to follow the Inca Manco over the Pass of

Panticalla, itself a snowy wilderness higher than

the summit of

Mont Blanc. In no part of the Peruvian Andes are there so many

beautiful snowy

peaks. Near by is the sharp, icy pinnacle of Mt. Veronica (elevation

19,342

ft.). Not faraway is another magnificent snow-capped peak, Mt.

Salcantay,

20,565 feet above the sea. Near Salcantay is the sharp needle of Mt.

Soray

(19,435 ft.), while to the west of it are Panta (18,590

ft.) and Soiroccocha (18,197 ft.). On the

shoulders of these mountains are unnamed glaciers and little valleys

that have

scarcely ever been seen except by some hardy, prospector or inquisitive

explorer. These valleys are to be reached only through passes where the

traveler is likely to be waylaid by violent storms of hail and snow.

During the

rainy season a large part of Uilcapampa is absolutely impenetrable.

Even in the

dry season the difficulties of transportation are very great. The most

sure-footed mule is sometimes unable to use the trails without

assistance from

man. It was an ideal place for the Inca Manco.

The conquistador,

Cieza de Leon, who wrote in 1550 a graphic account of

the wars of Peru,

says that Manco took with him a “great quantity of treasure, collected

from

various parts ... and many loads of rich clothing of wool, delicate in

texture

and very beautiful and showy.” The Spaniards were absolutely unable to

conceive

of the ruler of a country traveling without rich “treasure.” It is

extremely

doubtful whether Manco burdened himself with much gold or silver.

Except for

ornament there was little use to which he could have put the precious

metals

and they would have served only to arouse the cupidity of his enemies.

His

people had never been paid in gold or silver. Their labor was his due,

and only

such part of it as was needed to raise their own crops and make their

own

clothing was allotted to them; in fact, their lives were in his hands

and the

custom and usage of centuries made them faithful followers of their

great

chief. That Manco, however, actually did carry off with him beautiful

textiles,

and anything else which was useful, may be taken for granted. In

Uiticos, safe

from the armed forces of his enemies, the Inca was also able to enjoy

the

benefits of a delightful climate, and was in a well-watered region

where corn,

potatoes, both white and sweet, and the fruits of the temperate and

sub-tropical regions easily grow. Using this as a base, he was

accustomed to sally

forth against the Spaniards frequently

and in unexpected directions. His raids were usually successful. It was relatively easy for

him, with a handful

of followers, to dash out of the mountain fastnesses cross the

Apurirnac River

either by swimming or on primitive rafts, and reach the great road

between

Cuzco and Lima, the principal highway of Peru. Officials and merchants

whose

business led them over this route found it extremely precarious. Manco

cheered

his followers by making them realize that in these raids they were

taking sweet

revenge on the Spaniards for what they had done to Peru. It is

interesting to

note that Cieza de Leon justifies Manco in his attitude, for the

Spaniards had

indeed “seized his inheritance, forcing him to leave his native land,

and to

live in banishment.”

Manco’s success in

securing

such a place of refuge,

and in using it as a base from which he could frequently annoy his

enemies, led

many of the Orejones of Cuzco to follow him. The

Inca chiefs were called

Orejones, “big ears,” by the

Spaniards because the lobes of their ears had been enlarged

artificially to

receive the great gold earrings which they were fond of wearing. Three

years

after Manco’s retirement to the wilds of Uilcapampa there was born in

Cuzco in

the year 1539, Garcilasso Inca de la Vega, the son of an Inca princess

and one

of the conquistadores.

As a small child

Garcilasso

heard of the activities

of his royal relative. He left Peru as a boy and spent the rest of his

life in

Spain. After forty years in Europe he wrote, partly from memory, his

“Royal

Commentaries,” an account of the country of his Indian ancestors. Of

the Inca

Manco, of whom he must frequently have heard uncomplimentary reports as

a

child, he speaks apologetically. He says: “In the time of Manco Inca,

several

robberies were committed on the road by his subjects; but still they

had that

respect for the Spanish Merchants that they let them go free and never

pillaged

them of their wares and merchandise, which were in no manner useful to

them;

howsoever they robbed the Indians of their cattle [llamas and alpacas],

bred in

the countrey.... The Inca lived in the Mountains, which afforded no

tame

Cattel; and only produced Tigers and Lions and Serpents of twenty-five

and

thirty feet long, with other venomous insects.” (I am quoting from Sir

Paul

Rycaut’s translation, published in London in 1688.) Garcilasso says

Manco’s

soldiers took only “such food as they found in the hands of the

Indians; which

the Inca did usually call his own,” saying, “That he who was Master of

that

whole Empire might lawfully challenge such a proportion thereof as was

convenient to supply his necessary and natural support” — a reasonable

apology;

and yet personally I doubt whether Manco spared the Spanish merchants

and

failed to pillage them of their “wares and merchandise.” As will be

seen later,

we found in Manco’s palace some metal articles of European origin which

might

very well have been taken by Manco’s raiders. Furthermore, it should be

remembered that Garcilasso, although often quoted by Prescott, left

Peru when he

was sixteen years old and that his ideas were largely colored by his

long life

in Spain and his natural desire to extol the virtues of his mother’s

people, a

brown race despised by the white Europeans for whom he wrote.

The methods of

warfare and the

weapons used by Manco

and his followers at this time are thus described by Guzman. He says the Indians had no

defensive arms

such as helmets, shields, and armor, but used “lances, arrows, clubs,

axes,

halberds, darts, and slings, and another weapon which they call ayllas

(the bolas), consisting of three round stones sewn up in leather, and

each

fastened to a cord a cubit long. They throw these at the horses, and

thus bind

their legs together; and sometimes they will fasten a man’s arms to his

sides

in the same way. These Indians are so expert in the use of this weapon

that

they will bring down a deer with it in the chase. Their principal

weapon,

however, is the sling.... With it, they will hurl a huge stone with

such force

that it will kill a horse; in truth, the effect is little less great

than that

of an arquebus; and I have seen a stone, thus hurled from a sling,

break a

sword in two pieces which was held in a man’s hand at a distance of

thirty

paces.”

Manco’s raids finally

became so

annoying that

Pizarro sent a small force from Cuzco under Captain Villadiego to

attack the

Inca. Captain Villadiego found it impossible to use horses, although he

realized that cavalry was the “important arm against these Indians.”

Confident

in his strength and in the efficacy of his firearms, and anxious to

enjoy the

spoils of a successful raid against a chief reported to be traveling

surrounded

by his family “and with rich treasure,” he

pressed eagerly on, up through a lofty valley toward a defile in the

mountains,

probably the Pass of Panticalla. Here, fatigued and exhausted by their

difficult march and suffering from the effects of the altitude (16,000

ft.),

his men found themselves ambushed by the Inca, who with a small party,

“little

more than eighty Indians,” “attacked the Christians, who numbered

twenty-eight

or thirty, and killed Captain Villadiego and all his men except two or

three.”

To any one who has clambered over the passes of the Cordillera

Uilcapampa it is

not surprising that this military expedition was a failure or that the

Inca,

warned by keen-sighted Indians posted on appropriate vantage points,

could have

succeeded in defeating a small force of weary soldiers armed with the

heavy

blunderbuss of the seventeenth century. In a rocky pass, protected by

huge

boulders, and surrounded by quantities of natural ammunition for their

slings,

it must have been relatively simple for eighty Quichuas, who could

“hurl a huge

stone with such force that it would kill a horse,” to have literally

stoned to

death Captain Villadiego’s little company before they could have

prepared their

clumsy weapons for firing.

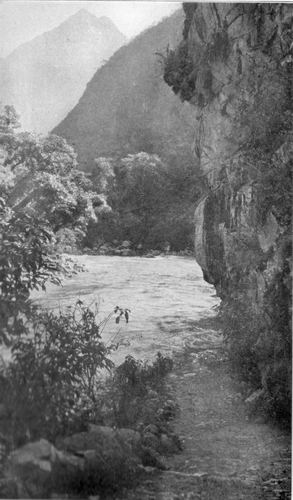

THE URUBAMBA CANYON

A reason for the safety of the Incas in Uilcapampa

The fugitives

returned to Cuzco

and reported their

misfortune. The importance of the reverse will be better appreciated if

one

remembers that the size of the force with which Pizarro conquered Peru

was less

than two hundred, only a few times larger than Captain Villadiego’s

company

which had been wiped out by Manco. Its significance is further

increased by the

fact that the contemporary Spanish writers, with all their tendency to

exaggerate, placed Manco’s force at only “a little more than eighty

Indians.”

Probably there were not even that many. The wonder is that the Inca’s

army was

not reported as being several thousand.

Francisco Pizzaro

himself now

hastily set out with a

body of soldiers determined to punish this young Inca who had inflicted

such a

blow on the prestige of Spanish arms, “but this attempt also failed,”

for the

Inca had withdrawn across the rivers and mountains of Uilcapampa to

Uiticos,

where, according to Cieza de Leon, he

cheered his

followers with the

sight of the heads of his enemies. Unfortunately for accuracy, the

custom of

displaying on the ends of pikes the heads of one’s enemies was European

and not

Peruvian. To be sure, the savage Indians of some of the Amazonian

jungles do

sometimes decapitate their enemies, remove the bones of the skull, dry

the

shrunken scalp and face, and wear the trophy as a mark of prowess just

as the

North American Indians did the scalps of their enemies. Such customs

had no place

among the

peace-loving Inca

agriculturists of central Peru. There were no Spaniards living with

Manco at

that time to report any such outrage on the bodies of Captain

Villadiego’s

unfortunate men. Probably the conquistadores

supposed that Manco did what the Spaniards would have

done under similar

circumstances.

Following the failure

of

Francisco Pizarro to

penetrate to Uiticos, his brother, Gonzalo, “undertook the pursuit of

the Inca

and occupied some of his passes and bridges,” but was unsuccessful in

penetrating the mountain labyrinth. Being less fool-hardy than Captain

Villadiego, he did not come into actual conflict with Manco. Unable to

subdue

the young Inca or prevent his raids on travelers from Cuzco to Lima,

Francisco

Pizarro, “with the assent of the royal officers who were with him,”

established

the city of Ayacucho at a convenient point on the road, so as to make

it secure

for travelers. Nevertheless, according to Montesinos, Manco caused the

good

people of Ayacucho quite a little trouble. Finally, Francisco Pizarro,

“having

taken one of Manco’s wives prisoner with other Indians, stripped and

flogged

her, and then shot her to death with arrows.”

Accounts of what

happened in

Uiticos under the rule

of Manco are not very satisfactory. Father Calancha, who published in

1639 his

“Coronica Moralizada,” or

“pious account of the missionary activities of the Augustinians” in

Peru, says

that the Inca Manco was obeyed by all the Indians who lived in a region

extending “for two hundred leagues and more toward the east and toward

the

south, where there were innumerable Indians in various provinces.” With

customary monastic zeal and proper religious fervor, Father Calancha

accuses

the Inca of compelling the baptized Indians who fled to him from the

Spaniards to

abandon their new faith, torturing those who would no longer worship

the old

Inca “idols.” This story need not be taken too literally, although

undoubtedly

the escaped Indians acted as though they had never been baptized.

Besides Indians

fleeing from

harsh masters, there

came to Uilcapampa, in 1542, Gomez Perez Diego Mendez, and half a dozen

other

Spanish fugitives, adherents of Almagro, “rascals,” says Calancha,

“worthy of

Manco’s favor.” Obliged by the civil wars of the conquistadores

to flee

from the Pizarros, they were glad enough to find a welcome in Uiticos.

To while

away the time they played games and taught the Inca checkers and chess,

as well

as bowling-on-the-green and quoits. Montesinos says they also taught

him to

ride horseback and shoot an arquebus. They took their games very

seriously and

occasionally violent disputes arose, one of which, as we shall see, was

to have

fatal consequences. They were kept informed by Manco of what was going

on in

the viceroyalty. Although “encompassed within craggy and lofty

mountains,” the

Inca was thoroughly cognizant of all those “revolutions” which might be

of

benefit to him.

Perhaps the most

exciting news

that reached Uiticos

in 1544 was in regard to the arrival of the first Spanish viceroy. He

brought

the New Laws, a result of the efforts of the good Bishop Las Casas to

alleviate

the sufferings of the Indians. The New Laws provided, among other

things, that

all the officers of the crown were to renounce their repartimientos

or holdings of Indian serfs, and that compulsory

personal service was to be entirely abolished. Repartimientos

given to the conquerors were not to pass to their

heirs, but were to revert to the king. In other words, the New Laws

gave

evidence that the Spanish crown wished to be kind to the Indians and

did not

approve of the Pizarros. This was good news for Manco and highly

pleasing to

the refugees. They persuaded the Inca to write a letter to the new

viceroy,

asking permission to appear before him and offer his services to the

king. The

Spanish refugees told the Inca that by this means he might some day

recover his

empire, “or at least the best part of it.” Their object in persuading

the Inca

to send such a message to the viceroy becomes apparent when we learn

that they

“also wrote as from themselves desiring a pardon for what was past” and

permission to return to Spanish dominions.

Gomez Perez, who

seems to have

been the active

leader of the little group, was selected to be the bearer of the

letters from

the Inca and the refugees. Attended by a dozen Indians whom the Inca

instructed

to act as his servants and bodyguard, he left Uilcapampa, presented his

letters

to the viceroy, and gave him “a large relation of the State and

Condition of

the Inca, and of his true and real designs to doe him service.” “The

Vice-king

joyfully received the news, and granted a full and ample pardon of all

crimes,

as desired. And as to the Inca, he made many kind expressions of love

and

respect, truly considering that the Interest of the Inca might be

advantageous

to him, both in War and Peace. And with this satisfactory answer Gomez

Perez

returned both to the Inca and to his companions.” The refugees were

delighted

with the news and got ready to return to king and country. Their

departure from

Uiticos Was prevented by a tragic accident, thus described by

Garcilasso.

“The Inca, to humour the Spaniards and entertain

himself with them, had given directions for making a bowling green;

When

playing one day with Gomez Perez, he came to have some quarrel and

difference

with this Perez about the measure of a Cast, Which often happened

between them;

for this Perez, being a person of a hot and fiery brain, without any

judgment

or understanding, would take the least occasion in the world to contend

with

and provoke the Inca.... Being no longer able to endure his rudeness,

the Inca

punched him on the breast, and bid him to consider with whom he talked.

Perez,

not considering in his heat and passion either his own safety or the

safety of

his Companions, lifted up his hand, and with the bowl struck the Inca

so

violently on the head, that he knocked him down. [He died three days

later.]

The Indians hereupon, being enraged by the death of their Prince,

joined

together against Gomez and the Spaniards, who, fled into a house, and

with their

Swords in their hands defended the door; the Indians set fire to the

house,

which being too hot for them, they sallied out into the Marketplace,

where the

Indians assaulted them and shot them with their Arrows until they had

killed

every man of them; and then afterwards, out of mere rage and fury they

designed

either to eat them raw as their custome was, or to burn them and cast

their

ashes into the river, that no sign or appearance might remain of them;

but at

length, after some consultation, they agreed to cast their bodies into

the open

fields, to be devoured by vulters and birds of the air, which they

supposed to

be the highest indignity and dishonour that they could show to their

Corps.”

Garcilasso concludes: “I informed myself very perfectly from those

chiefs and

nobles who were present and eye-witnesses of the unparalleled piece of

madness

of that rash and hair-brained fool; and heard them tell this story to

my mother

and parents with tears in their eyes.” There are many versions of the

tragedy.1

They all agree that a Spaniard murdered the Inca.

Thus, in 1545, the

reign of an

attractive and vigorous personality was brought to an abrupt close.

Manco left

three young sons, Sayri Tupac, Titu Cusi, and Tupac Amaru.

Sayri Tupac, although he

had not yet reached

his majority, became Inca in his father’s stead, and with the aid of

regents

reigned for ten years without disturbing his Spanish neighbors or being

annoyed

by them, unless the reference in Montesinos to a

proposed burning of bridges near Abancay, under date

of 1555, is

correct. By a curious lapse Montesinos ascribes this attempt to the

Inca Manco,

who had been dead for ten years. In 1555 there carne to Lima a new

viceroy, who

decided that it would be safer if young Sayri Tupac were within reach

instead

of living in the inaccessible wilds of Uilcapampa. The viceroy wisely

undertook

to accomplish this difficult matter through the Princess Beatrix Coya,

an aunt

of the Inca, who was living in Cuzco. She took kindly to the suggestion

and

dispatched to Uiticos a messenger, of the blood royal, attended by

Indian

servants. The journey was a dangerous one; bridges were down and the treacherous trails were

well-nigh

impassable. Sayri Tupac’s regents permitted the messenger to enter

Uilcapampa

and deliver the viceroy’s invitation, but were not inclined to believe

that it

was quite so attractive as appeared on the surface, even though brought

to them

by a kinsman. Accordingly, they kept the visitor as a hostage and sent

a

messenger of their own to Cuzco to see if any foul play could be

discovered,

and also to request that one John Sierra, a more trusted cousin, be

sent to

treat in this matter. All this took time.

In 1558 the viceroy,

becoming

impatient, dispatched

from Lima Friar Melchior and one John Betanzos, who had married the

daughter of

the unfortunate Inca Atahualpa and pretended to be very learned in his

wife’s

language. Montesinos says he was a “great linguist.” They started off

quite

confidently for Uiticos, taking with them several pieces of velvet and

damask,

and two cups of gilded silver as presents. Anxious to secure the honor

of being

the first to reach the Inca, they traveled as fast as they could to the

Chuquichaca bridge, “the key to the valley of Uiticos.” Here they were

detained

by the soldiers of the regents. A day or so later John Sierra, the

Inca’s

cousin from Cuzco, arrived at the bridge and was allowed to proceed,

while the

friar and Betanzos were still detained. John Sierra was welcomed by the

Inca

and his nobles, and did his best to encourage Sayri Tupac to accept the

viceroy’s offer. Finally John Betanzos and the friar were also sent for

and

admitted to the presence of the Inca, with the presents which the

viceroy had

sent. Sayri Tupac’s first idea was to remain free and independent as he

had

hitherto done, so he requested the ambassadors to depart immediately

with their

silver gilt cups. They were sent back by one of the western routes

across the

Apurimac. A few days later, however, after John Sierra had told him

some

interesting stories of life in Cuzco, the Inca decided to reconsider

the

matter. His regents had a long debate, observed the flying of birds and

the

nature of the weather, but according to Garcilasso “made no inquiries

of the

devil.” The omens were favorable and the regents finally decided to

allow the

Inca to accept the invitation of the viceroy.

Sayri Tupac, anxious

to see

something of the world,

went directly to Lima, traveling in a litter made of rich materials,

carried by

relays chosen from the three hundred Indians who attended him. He was

kindly

received by the viceroy, and then went to Cuzco, where he lodged in his

aunt’s

house. Here his relatives went to welcome him. “I, myself,” says

Garcilasso,

“went in the name of my Father. I found him then playing a certain game

used

amongst the Indians.... I kissed his hands, and delivered my Message;

he

commanded me to sit down, and presently they brought two gilded cups of

that

Liquor, made of Mayz [chicha] which

scarce contained four ounces of Drink; he took them both, and with his

own Hand

he gave one of them to me; he drank, and I pledged him, which as we

have said,

in the custom of Civility amongst them. This ceremony being past, he

asked me,

Why I did not meet him at Uilcapampa. I answered him, ‘Inca, as I am

but a

Young man, the Governours make no account of me, to place me in such

Ceremonies

as these! ‘How,’ replied the Inca, ‘I would rather have seen you than

all the

Friars and Fathers in Town.’ As I was going away I made him a

submissive bow

and reverence, after the manner of the Indians, who are of his Alliance

and

Kindred, at which he was so much pleased, that he embraced me heartily,

and

with much affection, as appeared by his Countenance.”

Sayri Tupac now

received the

sacred Red Fringe of

Inca sovereignty, was married to a princess of the blood royal, joined

her in

baptism, and took up his abode in the beautiful valley of Yucay, a

day’s

journey northeast of Cuzco, and never returned to Uiticos. His only

daughter

finally married a certain Captain Garcia, of whom more anon. Sayri

Tupac died

in 1560, leaving two brothers; the older, Titu Cusi Yupanqui,

illegitimate, and

the younger, Tupac Amaru, his rightful successor, an inexperienced

youth.

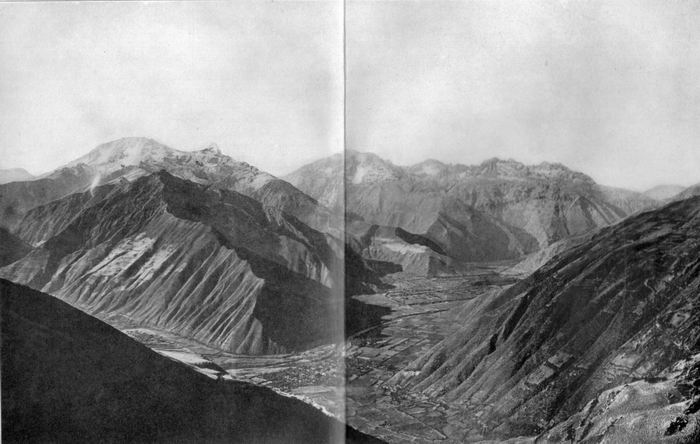

YUCAY, LAST HOME OF SAYRI TUPAC

The throne of Uiticos

was

seized by Titu Cusi. The

new Inca seems to have been suspicious of the untimely death of Sayri

Tupac,

and to have felt that the Spaniards were capable of more foul play. So

with his

half-brother he stayed quietly in Uilcapampa. Their first visitor, so

far as we

know, was Diego Rodriguez de Figueroa, who wrote an interesting account

of

Uiticos and says he gave the Inca a pair of scissors. He was

unsuccessful in

his efforts to get Titu Cusi to go to Cuzco. In time there came an

Augustinian

missionary, Friar Marcos Garcia, who, six years after the death of

Sayri Tupac,

entered the rough country of Uilcapampa, “a land of moderate wealth,

large

rivers, and the usual rains,” whose “forested mountains,” says Father

Calancha,

“are magnificent.” Friar Marcos had a hard journey. The bridges were

down, the

roads had been destroyed, and the passes blocked up. The few Indians

who did

occasionally appear in Cuzco from Uilcapampa said the friar could not

get there

“unless he should be able to change himself into a bird.” However, with

that

courage and pertinacity which have marked so many missionary

enterprises, Friar

Marcos finally overcame all difficulties and reached Uiticos.

The missionary

chronicler says

that Titu Cusi was

far from glad to see him and received him angrily. It worried him to

find that

a Spaniard had succeeded in penetrating his retreat. Besides, the Inca

was

annoyed to have any one preach against his “idolatries.” Titu Cusi’s

own story,

as written down by Friar Marcos, does not agree with Calancha’. Anyhow,

Friar

Marcos built a little church in a place called Puquiura, where many of

the

Inca’s people were then living. “He planted crosses in the fields and

on the

mountains, these being the best thing to frighten off devils.” He

“suffered

many insults at the hands of the chiefs and principal followers of the

Inca. Some

of them did it to please the Devil, others to flatter the Inca, and

many

because they disliked his sermons, in which he scolded them for their

vices and

abominated among his converts the possession of four or six wives. So

they

punished him in the matter of food, and forced him to send to Cuzco for

victuals. The Convent sent him hard-tack, which was for him a most

delicious

banquet.”

Within a year or

so another Augustinian missionary, Friar Diego Ortiz, left Cuzco alone

for

Uilcapampa. He suffered much on the road, but finally reached the

retreat of

the Inca and entered his presence in company with Friar Marcos.

“Although the

Inca was not too happy to see a new preacher, he was willing to grant

him an

entrance because the Inca... thought Friar Diego would not vex him nor

take the

trouble to reprove him. So the Inca gave him a license. They selected

the town

of Huarancalla, which was populous and well located in the midst of a

number of

other little towns and villages. There was a distance of two or three

days

journey from one Convent to the other. Leaving Friar Marcos in

Puquiura, Friar

Diego went to his new establishment and in a short time built a church,

a house

for himself, and a hospital, — all poor buildings made in a short

time.” He

also started a school for children, and became very popular as he went

about

healing and teaching. He had an easier time than Friar Marcos, who,

with less

tact and no skill as a physician, was located nearer the center of the

Inca

cult.

The principal shrine

of the

Inca is described by

Father Calancha as follows: “Close to Vitcos [or Uiticos] in a village

called

Chuquipalpa, is a House of the Sun, and in it a white rock over a

spring of

water where the Devil appears as a visible manifestation and was

worshipped by

those idolators. This

was the principal

mochadero of those forested mountains. The

word ‘mochadero’2

is the common name which the Indians apply to their places of worship.

In other

words it is the only where They practice the sacred ceremony of

kissing. The

origin of this, the principal part of their ceremonial, is that very

practice,

which Job abominates when he solemnly clears himself of all offence

before God

and says to Him: ‘Lord, all these punishments and even greater burdens

would I

have deserved had I that which the blind Gentiles do when the sun

shines

resplendent or the moon shines clear and they

exult in their hearts and extend their hands toward

the sun and throw

kisses to it,’ an act of very grave iniquity which is equivalent to

denying the

true God.”

Thus does the

ecclesiastical

chronicler refer to the

practice in Peru of that particular form of worship of the heavenly

bodies

which was also widely spread in the East, in Arabia, ad Palestine and

was

inveighed against by Mohammed as well as the ancient Hebrew prophets.

Apparently this ceremony “of the most profound resignation and

reverence” was

practiced in Chuquipalpa, close to Uiticos, in the reign of the Inca

Titu Cusi.

Calancha

goes on to say: “In this white stone of the

aforesaid House of the Sun,

which is called Yurac Rumi [meaning, Quichua, a white rock], there

attends a

Devil who is Captain of a legion. He and his legionaries show great

kindness to

the Indian idolators, but great terrors to the Catholics. They abuse

with

hideous cruelties the baptized ones who now no longer worship them with

kisses,

and many of the Indians have died from the horrible frights these

devils have

given them.”

One day, when the

Inca and his

mother and their

principal chiefs and counselors were away from Uiticos on a visit to

some of

their outlying estates, Friar Marcos and Friar Diego decided to make a

spectacular attack on this particular Devil, who was at the great

“white rock

over a spring of water.” The two monks summoned all their converts to

gather at

Puquiura, in the church or the neighboring plaza, and asked each to

bring a

stick of firewood in order that they might burn up this Devil who had

tormented

them. “An innumerable multitude” came together on the day appointed.

The

converted Indians were most anxious to get even with this Devil who had

slain

their friends and inflicted wounds on themselves; the doubters were

curious to

see the result; the Inca priests were there to see their god defeat the

Christians’; while, as may readily be imagined, the rest of the

population came

to see the excitement. Starting out from Puquiura they marched to “the

Temple

of the Sun, in the village of Chuquipalpa, close to Uiticos.”

Arrived at the sacred

palisade,

the monks raised the

standard of the cross, recited their orisons, surrounded the spring,

the white

rock and the Temple of the Sun, and piled high the firewood. Then,

having

exorcised the locality, they called the Devil by all the vile names

they could

think of, to show their lack of respect, and finally commanded him

never to

return to this vicinity. Calling on Christ and the Virgin, they applied

fire to

the wood. “The poor Devil then fled roaring in a fury, and making the

mountains

to tremble.”

It took remarkable

courage on

the part of the two

lone monks thus to desecrate the chief shrine of the people among whom

they

were dwelling. It is almost incredible that in this remote valley,

separated

from their friends and far from the protecting hand of the Spanish

viceroy,

they should have dared to commit such an insult to the religion of

their hosts.

Of course, as soon as the Inca Titu Cusi heard of it, he was greatly

annoyed.

His mother was furious. They returned immediately to Puquiura. The

chiefs

wished to “slay the monks and tear them into small pieces,” and

undoubtedly would

have done so had it not been for the regard in which Friar Diego was

held. His

skill in curing disease had so endeared him to the Indians that even

the Inca

himself dared not punish him for the attack on the Temple of the Sun.

Friar

Marcos, however, who probably originated the plan, and had done little

to gain

the good will of the Indians, did not fare so well. Calancha says he

was stoned

out of the province and the Inca threatened to kill him if he ever

should

return. Friar Diego, particularly beloved by those Indians who came

from the

fever-stricken jungles in the lower valleys, was allowed to remain, and

finally

became a trusted friend and adviser of Titu Cusi.

One day a Spaniard

named

Romero, an adventurous

prospector for gold, was found penetrating the mountain valleys, and

succeeded

in getting permission from the Inca to see what minerals were there. He

was too

successful. Both gold and silver were found among the hills and he

showed

enthusiastic delight at his good fortune. The Inca, fearing that his

reports

might encourage others to enter Uilcapampa, put the unfortunate

prospector to

death, notwithstanding the protestations of Friar Diego. Foreigners

were not

wanted in Uilcapampa.

In the year 1570, ten

years

after the accession of

Titu Cusi to the Inca throne in Uiticos, a new Spanish viceroy came to

Cuzco.

Unfortunately for the Incas, Don Francisco de Toledo, an indefatigable

soldier

and administrator, was excessively bigoted, narrow-minded, cruel, and

pitiless.

Furthermore, Philip II and his Council of the Indies had decided that

it would

be worth while to make every effort to get the Inca out of Uiticos. For

thirty-five years the Spanish conquerors had occupied Cuzco and the

major

portion of Peru without having been able to secure the submission of

the

Indians who lived in the province of Uilcapampa. It would be a great

feather in

the cap of Toledo if he could induce Titu Cusi to come and live where

he would

always be accessible to Spanish authority.

During the ensuing

rainy

season, after an unusually

lively party, the Inca got soaked, had a chill, and was laid low. In

the

meantime the viceroy had picked out a Cuzco soldier, one Tilano de

Anaya, who

was well liked by the Inca, to try to persuade Titu Cusi to come to

Cuzco. Tilano was instructed to

go by way of Ollantaytambo and the Chuquichaca bridge. Luck was against

him.

Titu Cusi’s illness was very serious. Friar Diego, his physician, had

prescribed the usual remedies. Unfortunately, all the monk’s skill was

unavailing and his royal patient died. The “remedies” were held by Titu

Cusi’s

mother and her counselors to be responsible. The poor friar had had to

stiffer

the penalty of death “for having caused the death of the Inca.”

The

third

son of Manco, Tupac Amaru, brought up as a playfellow of the Virgins of

the Sun

in the ‘Temple near Uiticos, and now happily married, was selected to rule the little

kingdom. His brows were

decked with the Scarlet Fringe of Sovereignty, but, thanks to the

jealous fear

of his powerful illegitimate brother, his training had not been that of

a

soldier. He was destined to have a brief, unhappy existence. When the

young

Inca’s counselors heard that a messenger was coming from the viceroy,

seven

warriors were sent to meet him on the road. Tilano was preparing to

spend the night

at the Chuquichaca bridge when he was attacked and killed.

The viceroy heard of

the murder

of his ambassador at

the same time that he learned of the martyrdom of Friar Diego. A blow

had been

struck at the very heart of Spanish domination; if the representatives

of the

Vice-Regent of Heaven and the messengers of the viceroy of Philip II

were not

inviolable, then who was safe? On Palm Sunday the energetic Toledo,

surrounded

by his council, determined to make war on the unfortunate young Tupac

Amaru and

give a reward to the soldier who would effect his capture. The council

was of

the opinion that “many Insurrections might be raised in that Empire by

this

young Heir.” “Moreover it was alledged,” says Garcilasso...... “That by

the

Imprisonment of the Inca, all that Treasure

might be discovered, which appertained to former kings,

together with that

Chain of Gold, which Huayna Capac commanded to be made for himself to

wear on

the great and solemn days of their Festival”! Furthermore, the “Chain

of Gold

with the remaining Treasure belong’d to

his Catholic Majesty by right of Conquest”! Excuses were not wanting.

The Incas

must be exterminated.

The expedition was

divided into

two parts. One

company was sent by way of Limatambo to Curahuasi, to head off the Inca

in case

he should cross the Apurimac and try to escape by one of the routes

which had

formerly been used by his father, Manco, in his marauding expeditions.

The

other company, under General Martin Hurtado and Captain Garcia, marched

from

Cuzco by way of Yucay and Ollantaytambo. They were more fortunate than

Captain

Villadiego whose force, thirty-five years before, had been met and

destroyed at

the pass of Panticalla. That was in the days of the active Inca Manco.

Now

there was no force defending this important pass. They descended the

Lucumayo

to its junction with the Urubamba and came to the bridge of Chuquichaca.

The narrow suspension

bridge,

built of native

fibers, sagged deeply in the middle and swayed so threateningly over

the gorge

of the Urubamba that only one man could pass it at a time. The rapid

river was

too deep to be forded. There were

no

canoes. It would have been a difficult matter to have constructed

rafts, for

most of the trees that grow here are of hard wood and do not float. On

the

other side of the Urubamba was young Tupac Amaru, surrounded by his

councilors,

chiefs, and soldiers. The first. hostile forces which in Pizarro’s time

had

endeavored to fight their way into Uilcapampa had never been allowed by

Manco

to get as far as this. His youngest son, Tupac Amaru, had had no

experience in

these matters. The chiefs and nobles had failed to defend the pass; and

they

now failed to destroy the Chuquichaca bridge, apparently relying on

their

ability to take care of one Spanish soldier at a time and prevent the

Spaniards

from crossing the narrow, swaying structure. General Hurtado was not

taking any

such chances. He had brought with him one or two light mountain field

pieces,

with which the raw troops of the Inca were little acquainted. The sides

of the

valley at this point rise steeply from the river and the reverberations

caused

by gun fire would be fairly terrifying to those who had never heard

anything

like it before. A few volleys from the guns and the arquebuses, and the

Indians

fled pell-mell in every direction, leaving the bridge undefended.

Captain Garcia, who

had married

the daughter of

Sayri Tupac, was sent in pursuit of the Inca. His men found the road

“narrow in

the ascent, with forest on the right, and on the left a ravine of great

depth.”

It was only a footpath, barely wide enough for two men to pass. Garcia,

with

customary Spanish bravery, marched at the head of his company. Suddenly

out of

the thick forest an Inca chieftain named Hualpa, endeavoring to protect

the

flight of Tupac Amaru, sprang on Garcia, held him so that he could not

get at

his sword and endeavored to hurl him over the cliff. The captain’s life

was

saved by a faithful Indian servant who was following immediately behind

him,

carrying his sword. Drawing it from the scabbard “with much dexterity

and

animation,” the Indian killed Hualpa and saved his master’s life.

Garcia fought several

battles,

took some forts and

succeeded in capturing many prisoners. From them it was learned that

the Inca

had “gone inland toward the valley of Simaponte; and that he was flying

to the

country of the Manaries Indians, a warlike tribe and his friends, where

balsas

and canoes were posted to save him and enable him to escape.” Nothing

daunted

by the dangers of the jungle nor the rapids of the river, Garcia

finally

managed to construct five rafts, on which he put some of his soldiers.

Accompanying them himself, he descended the rapids, escaping death many

times

by swimming, and finally arrived at a place called Momori, only to find

that

the Inca, learning of their approach, had gone farther into the woods.

Garcia

followed hard after, although he and his men were by this time

barefooted and

suffering from want of food. They finally captured the Inca. Garcilasso

says

that Tupac Amaru, “considering that he had not People to make

resistance, and

that he was not conscious to himself of any Crime, or disturbance he

had done

or raised, suffered himself to be taken; choosing rather to entrust

himself in

the hands of the Spaniards, than to perish in those Mountains with

Famine, or

be drowned in those great Rivers.... The Spaniards in this manner

seizing on

the Inca, and on all the Indian Men and Women, who were in Company with

him,

amongst which was his Wife, two Sons, and a Daughter, returned with

them in Triumph

to Cuzco; to which place the Vice-King went, so soon as he was

in-formed of the

imprisonment of the poor Prince.” A mock trial was held. The captured

chiefs

were tortured to death with fiendish brutality. Tupac Amaru’s wife was

mangled

before his eyes. His own head was cut off and placed on a pole in the

Cuzco

Plaza. His little boys did not long survive. So perished the last of

the Incas,

descendants of the wisest Indian rulers America has ever seen.

BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE

LAST FOUR

INCAS

1534. The Inca Manco

ascends the throne of his fathers.

1536. Manco

flees

from Cuzco to Uiticos and Uilcapampa.

1542. Promulgation of

the “New

Laws.”

1545. Murder of Manco

and accession of his son Sayri

Tupac.

1555. Sayri

Tupac goes to Cuzco and Yucay.

1560. Death of Sayri

Tupac. His half brother Titu Cusi becomes Inca.

1566. Friar Marcos

reaches

Uiticos. Settles in

Puquiura.

1566. Friar Diego

joins him.

1508-9 (?). They burn

the House

of the Sun at Yurac

Rumi in Chuquipalpa.

1571. Titu Cusi

dies. Friar Diego suffers

martyrdom. Tupac Amaru becomes Inca.

1572. Expedition of

General

Martin Hurtado and

Captain Garcia de Loyola. Execution of Tupac Amaru.

_______________

1

Another version of this event is that the quarrel was over a game of chess between the Inca and Diego Mendez,

another of the refugees, who lost his temper and called the Inca a dog.

Angered

at the tone and language of his guest, the Inca gave him a blow with

his fist.

Diego Mendez thereupon drew a dagger and killed him. A totally

different

account from the one obtained by Garcilasso from his informants is that

in a

volume purporting to have been dictated to Friar Marcos by Manco’s son,

Titu

Cusi, twenty years after the event. I quote from Sir Clements Markham’s

translation:

“After these Spaniards had been

with my Father for several years in the said town of Viticos they were

one day,

with much good fellow-ship, playing at quoits with him; only them, my

Father

and me, who was then a boy [ten years old]. Without having any

suspicion,

although an Indian woman, named Banba, had said that the Spaniards

wanted to

murder the Inca, my Father was playing with them as usual. In this

game, just

as my Father was raising the quoit to throw, they all rushed upon him

with

knives, daggers and some swords. My Father, feeling himself wounded,

strove to

make some defence, but he was one and unarmed, and they were seven

fully armed;

he fell to the ground covered with wounds, and they left him for dead.

I, being

a little boy, and seeing my Father treated in this manner, wanted to go

where

he was to help him. But they turned furiously upon me, and hurled a

lance which

only just failed to kill me also. I was terrified and fled amongst some

bushes.

They looked for me, but could not find me. The Spaniards, seeing that

my Father

had ceased to breathe, went out of the gate, in high spirits, saying,

‘Now that

we have killed the Inca we have nothing to fear.’ But at this moment

the

captain Rimachi Yupanqui arrived with some Antis, and presently chased

them in

such sort that, before they could get very far along a difficult road,

they

were caught and pulled from their horses. They all had to suffer very

cruel

deaths and some were burnt. Notwithstanding his wounds my Father lived

for

three days.’’

Another version is

given by

Montesinos in his Anales. It is

more like Titu Cusi’s.

2 A

Spanish derivative from the Quichua mucha “a kiss.”

Muchani means

‘to adore, to reverence, to kiss the hands.’

Click  here to continue to the next chapter of Inca Lands

here to continue to the next chapter of Inca Lands

|