| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

VIII THE

OLDEST CITY IN SOUTH AMERICA Cuzco, the oldest

city in South

America, has changed

completely since Squier’s visit. In fact it has altered considerably

since my

own first impressions of it were published in “Across South America.”

To be

sure, there are still the evidences of antiquity to be seen on every

side; on

the other hand there are corresponding evidences of advancement.

Telephones,

electric lights, street cars, and the “movies” have come to stay. The

streets

are cleaner. If the modern traveler finds fault with some of the

conditions he

encounters he must remember that many of the achievements of the people

of

ancient Cuzco are not yet duplicated in his own country nor have they

ever been

equaled in any other part of the world. And modern Cuzco is steadily

progressing. The great square in front of the cathedral was completely

metamorphosed by Prefect Nunez in 1911; concrete walks and beds of

bright

flowers have replaced the market and the old cobblestone paving and

made the

plaza a favorite promenade of the citizens on pleasant evenings. The principal

market-place now

is the Plaza of San Francisco.

It is crowded with booths of every description. Nearly all of the

food-stuffs

and utensils used by the Indians may be bought here. Frequently

thronged with

Indians, buying and selling, arguing and jabbering, it affords,

particularly in

the early morning, a never-ending source of entertainment to one who is

fond of

the picturesque and interested in strange manners and customs. The retail merchants

of Cuzco

follow the very old

custom of congregating by classes. In one street are the dealers in

hats; in

another those who sell coca. The dressmakers and

tailors are nearly all

in one long arcade in a score or more of dark little shops. Their light

seems

to come entirely from the front door. The occupants are operators of

American

sewing-machines who not only make clothing to order, but always have on

hand a

large assortment of standard sizes and patterns. In another arcade are

the

shops of those who specialize in everything which appeals to the eye

and the

pocketbook of the arriero: richly decorated

halters, which are intended

to avert the Evil Eye from his best mules; leather knapsacks in which

to carry

his coca or other valuable articles; cloth cinches

and leather bridles;

raw-hide lassos, with which he is more likely to make a diamond hitch

than to

rope a mule; flutes to while away the weary hours of his journey, and

candles

to be burned before his patron saint as he starts for some distant

village; in

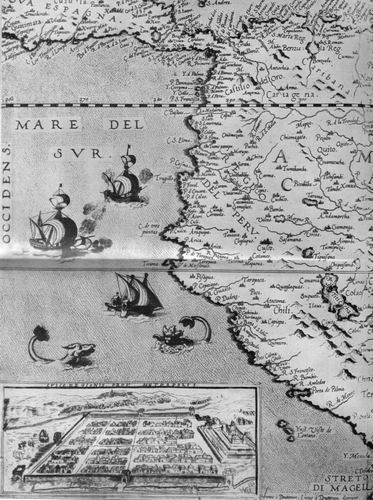

a word, all the paraphernalia of his profession.  MAP OF PERU AND VIEW OF CUZCO From the "Speculum Orbis Terrarum," Antwerp, 1578 In order to learn

more about

the picturesque

Quichuas who throng the streets of Cuzco it was felt to be important to

secure

anthropometric measurements of a hundred Indians. Accordingly, Surgeon

Nelson

set up a laboratory in the Hotel Central. His subjects were the

unwilling

victims of friendly gendarmes who went

out into the streets with orders to bring for examination

only pure-blooded Quichuas. Most of the Indians showed no resentment

and were

in the end pleased and surprised to find themselves the recipients of a

small

silver coin as compensation for loss of time. One might have

supposed that a

large proportion of

Dr. Nelson’s subjects would have claimed Cuzco as their native place,

but this

was not the case. Actually fewer Indians came from the city itself than

from

relatively small towns like Anta, Huaracondo, and Maras. This may have

been due

to a number of causes. In the first place, the gendarmes

may have preferred to arrest strangers from distant

villages, who would submit more willingly. Secondly, the city folk were

presumably more likely to be in their shops attending to their business

or

watching their wares in the plaza, an occupation which the gendarmes could not interrupt. On the other

hand it is also probably true that the residents of Cuzco are of more

mixed

descent than those of remote villages, where even to-day one cannot

find more

than two or three individuals who speak Spanish. Furthermore, the

attention of

the gendarmes might have been

drawn

more easily to the quaintly caprisoned Indians temporarily in from the

country,

where city fashions do not prevail, than to those who through long

residence in

the city had learned to adopt a costume more in accordance with

European

notions. In 1870, according to Squier, seven eighths of the population

of Cuzco

were still pure Indian.

Even to-day a

large proportion of the individuals whom one sees in the streets

appears to be

of pure aboriginal ancestry. Of these we found that many are visitors

from

outlying villages. Cuzco is the Mecca of the most densely populated

part of the

Andes. Probably a large part

of its

citizens are of mixed

Spanish and Quichua ancestry. The Spanish conquistadores

did not bring European women with them. Nearly all took

native wives. The Spanish race is composed of such an extraordinary

mixture of

peoples from Europe and northern Africa, Celts, Iberians, Romans, and

Goths, as

well as Carthaginians, Berbers, and Moors, that the Hispanic peoples

have far

less antipathy toward intermarriage with the American race than have

the

Anglo-Saxons and Teutons of northern Europe. Consequently, there has

gone on

for centuries intermarriage of Spaniards and Indians with results which

are

difficult to determine. Some writers have said there were once 200,000

people

in Cuzco. With primitive methods of transportation it would be very

difficult

to feed so many. Furthermore, in 1559, there were, according to

Montesinos,

only 20,000 Indians in Cuzco. One of the charms of

Cuzco is

the juxtaposition of

old and new. Street cars clanging over steel rails carry crowds of

well-dressed

Cuzcenos past Inca walls to greet their friends at the railroad

station. The

driver is scarcely able by the most vigorous application of his brakes

to

prevent his mules from crashing into a compact herd of quiet,

supercilious

llamas sedately engaged in bringing small sacks of potatoes to the

Cuzco

market. The modern convent of La Merced is built of stones taken from

ancient

Inca structures. Fastened to ashlars which left the Inca stonemason’s

hands six

or seven centuries ago, one sees a bill-board advertising Cuzco’s

largest moving-picture

theater. On the 2d of July, 1915, the performance was for the benefit

of the

Belgian Red Cross! Gazing in awe at this sign were Indian boys from

some remote

Andean village where the custom is to wear ponchos with broad fringes,

brightly

colored, and knitted caps richly decorated with tasseled tops and

elaborate

ear-tabs, a costume whose design shows no trace of European influence.

Side by

side with these picturesque visitors was a barefooted Cuzco urchin clad

in a

striped jersey, cloth cap, coat, and pants of English pattern. One sees electric

light wires

fastened to the walls

of houses built four hundred years ago by the Spanish conquerors, walls

which

themselves rest on massive stone foundations laid by Inca masons

centuries

before the conquest. In one place telephone wires intercept one’s view

of the

beautiful stone fašade of an old Jesuit Church, now part of the

University of

Cuzco. It is built of reddish basalt from the quarries of Huaccoto,

near the

twin peaks of Mt. Picol. Professor Gregory says that this Huaccoto

basalt has a

softness and uniformity of texture which renders it peculiarly suitable

for

that elaborately carved stonework which was so greatly desired by

ecclesiastical architects of the sixteenth century. As compared with

the dense

diorite which was extensively used by the Incas, the basalt weathers

far more

rapidly. The rich red color of the weathered portions gives to the

Jesuit

Church an atmosphere of extreme age. The courtyard of the University,

whose

arcades echoed to the feet of learned Jesuit teachers long before Yale

was

founded, has recently been paved with concrete, transformed into a

tennis

court, and now echoes to the shouts of students to whom Dr. Giesecke,

the

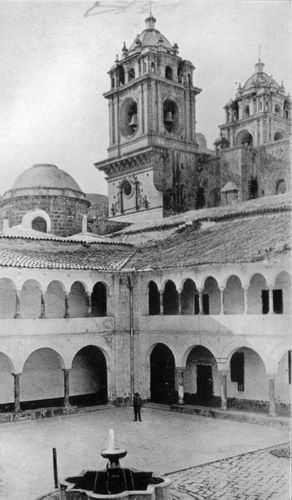

successful president, is teaching the truth of the ancient axiom, “Mens sana in corpore sano.”  TOWERS OF JESUIT CHURCH WITH CLOISTERS AND TENNIS COURT OF UNIVERSITY, CUZCO Modern Cuzco is a

city of about

20,000 people.

Although it is the political capital of the most important department

in

southern Peru, it had in 1911 only one hospital — a semi-public,

non-sectarian

organization on the west of the city, next door to the largest

cemetery. In

fact, so far away is it from everything else and so close to the

cemetery that

the funeral wreaths and the more prominent monuments are almost the

only

interesting things which the patients have to look at. The building has

large

courtyards and open colonnades, which would afford ideal conditions for

patients able to take advantage of open-air treatment. At the time of

Surgeon

Erving’s visit he found the patients were all kept in wards whose

windows were

small and practically always closed and shuttered, so that the

atmosphere was

close and the light insufficient. One could hardly imagine a stronger

contrast

than exists between such wards and those to which we are accustomed in

the

United States, where the maxi-mum of sunlight and fresh air is sought

and

patients are encouraged to sit out-of-doors, and even have their cots

on

porches. There was no resident physician. The utmost care was taken

throughout

the hospital to have everything as dark as possible, thus conforming to

the

ancient mountain traditions regarding the evil effects of sunlight and

fresh

air. Needless to say, the hospital has a high mortality and a very poor

local

reputation; yet it is the only hospital in the Department. Outside of

Cuzco, in

all the towns we visited, there was no provision for caring for the

sick except

in their own homes. In the larger places there are shops where sonic of

the

more common drugs may be obtained, but in the great majority of towns

and

villages no modern medicines can be purchased. No wonder President Giesecke, of the

University, is urging his

students to play football and tennis. On the slopes of the

hill which

overshadows the

University are the interesting terraces of Colcampata. Here, in 1571,

lived

Carlos Inca, a cousin of Inca Titu Cusi, one of the native rulers who

succeeded

in maintaining a precarious existence in the wilds of the Cordillera

Uilcapampa

after the Spanish Conquest. In the gardens of Colcampata is still

preserved one

of the most exquisite bits of Inca stonework to be seen in Peru. One

wonders

whether it is all that is left of a fine palace, or whether it

represents the

last efforts of a dying dynasty to erect a suitable residence for Titu

Cusi’s

cousin. It is carefully preserved by Don Cesare Lomellini, the leading

business

man of Cuzco, a merchant prince of Italian origin, who is at once a

banker, an

exporter of hides and other country produce, and an importer of

merchandise of

every description, including pencils and sugar mills, lumber and hats,

candy

and hardware. He is also an amateur of Spanish colonial furniture as

well as of

the beautiful pottery of the Incas. Furthermore, he has always found

time to

turn aside from the pressing cares of his large business to assist our

expeditions. He has frequently brought us in touch with the owners of

country

estates, or given us letters of introduction, so that our paths were

made easy.

He has provided us with storerooms for our equipment, assisted us in

procuring

trustworthy muleteers, seen to it that we were not swindled in local

purchases

of mules and pack saddles, given us invaluable advice in over-coming

difficulties, and, in a word, placed himself wholly at our disposal,

just as

though we were his most desirable and best-paying clients. As a matter

of fact,

he never was willing to receive any compensation for the many favors he

showed

us. So important a factor was he in the success of our expeditions that

he

deserves to be gratefully remembered by all friends of exploration. Above his country

house at

Colcampata is the hill of

Sacsahuaman. It is possible to scramble up — its face, but only by

making more

exertion than is desirable at this altitude, 11,900 feet. The easiest

way to

reach the famous “fortress” is by following the course of the little

Tullumayu,

“Feeble Stream,” the easternmost of the three canalized streams which

divide

Cuzco into four parts. On its banks one first passes a tannery and

then, a

short distance up a steep gorge, the remains of an old mill. The stone

flume

and the adjoining ruins are commonly ascribed by the people of Cuzco

to-day to

the Incas, but do not look to me like Inca stonework. Since the Incas

did not

understand the mechanical principle of the wheel, it is hardly likely

that they

would have known how to make any use of water power. Finally, careful

examination of the flume discloses the presence of lead cement, a

substance

unknown in Inca masonry. A little farther up

the stream

one passes through a

massive megalithic gateway and finds one’s self in the presence of the

astounding gray-blue Cyclopean walls of Sacsahuaman

described in “Across South America.” Here the

ancient builders

constructed three great terraces, which extend one above another for a

third of

a mile across the hill between two deep gulches. The lowest terrace of

the

“fortress” is faced with colossal boulders, many of which weigh ten

tons and

some weigh more than twenty tons, yet all are fitted together with the

utmost

precision. I have visited Sacsahuaman repeatedly. Each time it

invariably overwhelms

and astounds. To a superstitious Indian who sees these walls for the

first

time, they must seem to have been built by gods. About a mile

northeast of

Sacsahuaman are several

small artificial hills, partly covered with vegetation, which seem to

be composed

entirely of gray-blue rock chips — chips from the great limestone

blocks

quarried here for the “fortress” and later conveyed with the utmost

pains down

to Sacsahuaman. They represent the labor of countless thou-sands of

quarrymen.

Even in modern times, with steam drills, explosives, steel tools, and

light

railways, these hills would be noteworthy, but when one pauses to

consider that

none of these mechanical devices were known to the ancient stone-masons

and

that these mountains of stone chips were made with stone tools and were

all

carried from the quarries by hand, it fairly staggers the imagination. The ruins of

Sacsahuaman

represent not only an

incredible amount of human labor, but also a very remarkable

governmental

organization. That thousands of people could have been spared from

agricultural

pursuits for so long a time as was necessary to extract the blocks from

the

quarries, hew them to the required shapes, transport them several miles

over

rough country, and bond them together in such an intricate manner,

means that

the leaders had the brains and ability to organize and arrange the

affairs of a

very large population. Such a folk could hardly have spent much time in

drilling or preparing for warfare. Their building operations required

infinite

pains, endless time, and devoted skill. Such qualities could hardly

have been

called forth, even by powerful monarchs, had not the results been

pleasing to

the great majority of their people, people who were primarily

agriculturists.

They had learned to avert hunger and famine by relying on carefully

built,

stone-faced terraces, which would prevent their fields being carried

off and

spread over the plains of the Amazon. It seems to me possible that

Sacsahuaman

was built in accordance with their desires to please their gods. Is it

not

reasonable to suppose that a people to whom stone-faced terraces meant

so much

in the way of life-giving food should have sometimes built massive

terraces of

Cyclopean character, like Sacsahuaman, as an offering to the deity who

first

taught them terrace construction? This seems to me a more likely object

for the

gigantic labor involved in the construction of Sacsahuaman than its

possible

usefulness as a fortress. Equally strong defense, against an enemy

attempting

to attack the hilltop back of Cuzco might have been constructed of

smaller

stones in an infinitely shorter time, with far less labor and pains. Such a display of the

power to

control the labor of

thousands of individuals and force them

to super-human efforts on an unproductive

undertaking, which in its

agricultural or strategic results was out of all proportion to the

obvious

cost, might have been caused by the supreme vanity of a great soldier.

On the

other hand, the ancient Peruvians were religious rather than warlike,

more

inclined to worship the sun than to fight great battles. Was

Sacsahuaman due to

the desire to please at whatever cost, the god that fructified the

crops which

grew on terraces? It is not surprising that the Spanish conquerors,

warriors

themselves and descendants of twenty generations of a fighting race,

accustomed

as they were to the salients of European fortresses, should have looked

upon

Sacsahuaman as a fortress. To them the military use of its bastions was

perfectly obvious. The value of its salients and reentrant angles was

not

likely to be overlooked,

for it had

been only recently acquired by their crusading ancestors. The height

and

strength of its powerful walls enabled it to be of the greatest service

to the

soldiers of that day. They saw that it was virtually impregnable for

any

artillery with which they were familiar. In fact, in the wars of the

Incas and

those which followed Pizarro’s entry into Cuzco, Sacsahuaman was

repeatedly

used as a fortress. So it probably never

occurred

to the Spaniards that

the Peruvians, who knew nothing of explosive powder or the use of

artillery,

did not construct Sacsahuaman in order to withstand such a siege as the

fortresses of Europe were only too familiar with. So natural did it

seem to the

first Europeans who saw it to regard it as a fortress that it has

seldom been

thought of in any other way. The fact that the sacred city of Cuzco was

more

likely to be attacked by invaders coming up the valley, or even over

the gentle

slopes from the west, or through the pass from the north which for

centuries

has been used as part of the main highway of the central Andes, never

seems to

have troubled writers who regarded Sacsahuaman essentially as a

fortress. It

may be that Sacsahuaman was once used as a place where the votaries of

the sun

gathered at the end of the rainy season to celebrate the vernal

equinox, and at

the summer solstice to pray for the sun’s return from his “farthest

north.” In

any case I believe that the enormous cost of its construction shows

that it was

probably intended for religious rather than military purposes. It is

more

likely to have been an ancient shrine than a mighty fortress. It now becomes

necessary, in

order to explain my

explorations north of Cuzco, to ask the reader’s attention to a brief

account

of the last four Incas who ruled over any part of Peru. |