| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XXV ALL ABOARD: THE RETURN TO NEW ZEALAND An Oar Breaks: Disaster Averted: Last View of Winter Quarters: Supplies left at Cape Royds: New Coast-line: Anchored at Mouth of Lord's River, Stewart Island, March 22: Arrived Lyttelton, March 25, 1909 THE Nimrod,

with the members of the Northern

Party aboard, got back to

the winter quarters on February 11 and landed Mawson. The hut party at

this

period consisted of Murray, Priestley, Mawson, Day, and Roberts. No

news had

been heard of the Southern Party, and the depot party, commanded by

Joyce, was

still out. The ship lay under Glacier Tongue most of the time, making

occasional visits to Hut Point in case some sf the men should have

returned. On

February 20 it was found that the depot party had reached Hut Point,

and had

not seen th.e Southern Party. The temperature was becoming lower, arid

the

blizzards were more frequent. The

instructions left by me had

provided that if we had not returned by February 25, a party was to be

landed

at Hut Point, with a team of dogs, and on March 1 a search-party was to

go

south. In connection with landing party, Murray showed Captain Evans my

full

instructions that the party was to be landed on the 25th, and on this

being

understood the Nimrod left Cape

Royds

on the 21st with the party, whilst Murray remained in charge at Cape

Royds,

which was now cut off by sea from Hut Point. Murray was in no way

responsible

for the failure of that party to be landed, and this is a point I did

not make

clear in the first edition of my book; it is therefore due to Murray to

make

this explanation. All arrangements being completed, most of the members

of the

expedition then on board went ashore at Cape Royds to get the last of

their

property packed ready for departure. The ship was lying under Glacier

Tongue

when I arrived at Hut Point with Wild on February 28 and after I had

been

landed with the relief party in order to bring in Adams and Marshall,

it

proceeded to Cape Royds in order to take on board the remaining members

of the

shore-party and some specimens and stores. The Nimrod

anchored a short distance from the

shore, and two boats were

launched. The only spot convenient for embarkation near the ship's

anchorage

was at a low ice cliff in Backdoor Bay. Everything had to be lowered by

ropes

over the cliff into the boats. Some hours were spent in taking on board

the last

of the collections, the private property, and various stores. A stiff breeze

was blowing, making

work with the boats difficult, but by 6 A.M. on March 2 there remained

to be

taken on board only the men and dogs. The operation of lowering the

dogs one by

one into the boats was necessarily slow, and while it was in progress

the wind

freshened to blizzard force, and the sea began to run dangerously. The

waves

had deeply undercut the ice-cliff, leaving a projecting shelf. One

boat, in

charge of Davis, succeeded in reaching the ship, but a second boat,

commanded

by Harbord, was less fortunate. It was heavily loaded with twelve men

and a

number of dogs, and before it had proceeded many yards from the shore

an oar

broke. The Nimrod was forced to

slip

her moorings and steam out of the bay, as the storm had become so

severe that

she was in danger of dragging her anchors and going on the rocks. An

attempt to

float a buoy to the boat was not successful, and for some time Harbord

and the

men with him were in danger. They could not get out of the bay owing to

the

force of the sea, and the projecting shelf of ice threatened disaster

if they

approached the shore. The flying spray had encased the men in ice, and

their

hands were numb and hall-frozen. At the end of an hour they managed to

make

fast to a line stretched from an anchor a few yards from the cliff, the

men who

had remained on shore pulling this line taut. The position was still

dangerous,

but all the men and dogs were hauled up the slippery ice-face into

safety before

the boat sank. Hot drinks were soon ready in the hut, and the men dried

their

clothes as best they could before the fire. Nearly all the bedding had

been

sent on board, and the temperature was low, but they were thankful to

have

escaped with their lives. The weather was

bitter on the

following morning (March 3), and the Nimrod,

which had been sheltering under Glacier Tongue, came back to Cape

Royds. A

heavy sea was still running, but a new landing-place was selected in

the

shelter of the cape, and all the men and dogs were got aboard. The ship

went

back to the Glacier Tongue anchorage to wait for the relief party.  READY TO START HOME About ten

o'clock that night

Mackintosh was walking the deck engaged in conversation with some other

members

of the expedition. Suddenly he became excited and said, " I feel that

Shackleton has arrived at Hut Point." He was very anxious that the ship

should go up to the Point, but nobody gave much attention to him. Then

Dunlop

advised him to go up to the crow's-nest if he was sure about it, and

look for a

signal. Mackintosh went aloft, and immediately saw our flare at Hut

Point. The

ship at once left for Hut Point, reaching it at midnight, and by 2 A.M.

on

March 4 the entire expedition was safe on board. There was now

no time to be lost if

we were to attempt to complete our work. The season was far advanced,

and the

condition of the ice was a matter for anxiety, but I was most anxious

to

undertake exploration with the ship to the westward, towards Adelie

Land, with

the idea of mapping the coast-line in that direction. As soon as all

the

members of the expedition were on board the Nimrod,

therefore, I gave orders to steam north, and in a very short time we

were under

way. It was evident that the sea in our neighbourhood would be frozen

over

before many hours had passed, and although I had foreseen the

possibility of

having to spend a second winter in the Antarctic when making my

arrangements,

we were all very much disinclined to face the long wait if it could be

avoided.

I wished first to round Cape Armitage and pick up the geological

specimens and

gear that had been left at Pram Point, but there was heavy ice coining

out from

the south, and this meant imminent risk of the ship being caught and

perhaps

"nipped." I decided to go into shelter under Glacier Tongue in the

little inlet on the north side for a few hours, in the hope that the

southern

wind, that was bringing out the ice, would cease and that we would then

be able

to return and secure the specimens and gear. This was about two o'clock

on the

morning of March 4, and we members of the Southern Party turned in for

a

much-needed rest. At eight

o'clock on the morning of

the 4th we again went down the sound. Young ice was forming over the

sea, which

was now calm, the wind having entirely dropped, and it was evident that

we must

be very quick if we were to escape that year. We brought the Nimrod right alongside the pressure ice

at

Pram Point, and I pointed out the little depot on the hillside.

Mackintosh at

once went off with a party of men to bring the gear and specimens down,

while

another party went out to the seal rookery to see if they could find a

peculiar

seal that we had noticed on our way to the hut on the previous night.

The seal

was either a new species or the female of the Ross seal. It was a small

animal,

about four feet six inches long, with a broad white band from its

throat right

down to its tail on the underside. If we had been equipped with knives

on the

previous night we would have despatched it, but we had no knives and

were,

moreover, very tired, and we therefore left it. The search for the seal

proved

fruitless, and as the sea was freezing over behind us I ordered all the

men on

board directly the stuff from the depot had been got on to the deck,

and the Nimrod once more steamed

north. The

breeze soon began to freshen, and it was blowing hard from the south

when we

passed the winter quarters at Cape Royds. We all turned out to give

three

cheers and to take a last look at the place where we had spent so many

happy

days. The hut was not exactly a palatial residence, and during our

period of

residence in it we had suffered many discomforts, not to say hardships,

but, on

the other hand, it had been our home for a year that would always live

in our

memories. We had been a very happy little party within its walls, and

often

when we were far away from even its measure of civilisation it had been

the

Mecca of all our hopes and dreams. We watched the little hut fade away

in the

distance with feelings almost of sadness, and there were few men aboard

who did

not cherish a hope that some day they would once more live strenuous

days under

the shadow of mighty Erebus. I left at the

winter quarters on

Cape Royds a supply of stores sufficient to last fifteen men for one

year. The

vicissitudes of life in the Antarctic are such that such a supply might

prove

of the greatest value to some future expedition. The hut was locked up

and the

key hung up outside where it would be easily found, and we readjusted

the

lashing of the hut so that it might be able to withstand the attacks of

the

blizzards during the years to come. Inside the hut I left a letter

stating what

had been accomplished by the expedition, and giving some other

information that

might be useful to a future party of explorers. The stores left in the

hut

included oil, flour, jams, dried vegetables, biscuits, pemmican,

plasmon,

matches, and various tinned meats, as well as tea, cocoa, and necessary

articles of equipment. If any party has to make use of our hut in the

future,

it will find there everything required to sustain life. The wind was

still freshening as we

went north under steam and sail on March 4, and it was fortunate for us

that

this was so, for the ice that had formed on the sea water in the sound

was

thickening rapidly, assisted by the old pack, of which a large amount

lay

across our course. I was anxious to pick up a depot of geological

specimens on

Depot Island, left there by the Northern Party, and with this end in

view the Nimrod was taken on a more

westerly

course than would otherwise have been the case. The wind, however, was

freshening to a gale, and we were passing through streams of ice, which

seemed

to thicken as we neared the shore. I decided that it would be too risky

to send

a party off for the specimens, as there was no proper lee to this small

island,

and the consequences of even a short delay might be serious. I

therefore gave

instructions that the courso should be altered to due north. The

following wind

helped us, and on the morning of March 6 we were off Cape Adare. I

wanted to

push between the Balleny Islands and the mainland, and make an attempt

to

follow the coast-line from Cape North westward, so as to link it up

with Adelie

Land. No ship had ever succeeded in penetrating to the westward of Cape

North,

heavy pack having been encountered on the occasion of each attempt. The

Discovery had passed through

the Balleny

Islands and sailed over part of the so-called Wilkes Land of the maps,

but the

question of the existence of this land in any other position had been

left

open. We steamed

along the pack-ice, which

was beginning to thicken, and although we did not manage to do all that

I had

hoped, we had the satisfaction of pushing our little vessel along that

coast to

longitude 166° 14' East, latitude 69° 47' South, a point further west

than had

been reached by any previous expedition. On the morning of March 8 we

saw,

beyond Cape North, a new coast-line extending first to the southwards

and then

to the west for a distance of over forty-five miles. We took angles and

bearings, and Marston sketched the main outlines. We were too far away

to take

any photographs that would have been of value, but the sketches show

very

clearly the type of the land. Professor David was of opinion that it

was the northern

edge of the polar plateau. The coast seemed to consist of cliffs, with

a few

bays in the distance. We would all have been glad of an opportunity to

explore

the coast thoroughly, but that was out of the question; the ice was

getting

thicker all the time, and it was becoming imperative that we should

escape to

clear water without further delay. There was no chance of getting

farther west

at that point, and as the new ice was forming between the old pack of

the

previous year and the land, we were in serious danger of being frozen

in for

the winter at a place where we could not have done any geological work

of

importance. We therefore moved north along the edge of the pack, making

as much

westing as possible, in the direction of the Balleny Islands. I still

hoped

that it might be possible to skirt them and find Wilkes Land. It was

awkward

work, and at times the ship could hardly move at all. Finally, about

midnight on March 9,

I saw that we must go north, and the course was set in that direction.

We were

almost too late, for the ice was closing in and before long we were

held up,

the ship being unable to move at all. The situation looked black, but

we

discovered a lane through which progress could be made, and in the

afternoon of

the 10th we were in fairly open water, passing through occasional lines

of

pack. Our troubles were over, for we had a good voyage up to New

Zealand, and

on March 22 dropped anchor at the mouth of Lord's river, on the south

side of

Stewart Island. I did not go to a port because I wished to get the news

of the

expedition's work through to London before we faced the energetic

newspaper

men. That was a

wonderful day to all of

us. For over a year we had seen nothing but rocks, ice, snow, and sea.

There

had been no colour and no softness in the scenery of the Antarctic; no

green

growth had gladdened our eyes, no musical notes of birds had come to

our ears.

We had had our work, but we had been cut off from most of the lesser

things

that go to make life worth while. No person who has not spent a period

of his

life in those "stark and sullen solitudes that sentinel the Pole"

will understand fully what trees_ and flowers, sun-flecked turf and

running

streams mean to the soul of a man. We landed on the stretch of beach

that

separated the sea from the luxuriant growth of the forest, and

scampered about

like children in the sheer joy of being alive. I did not wish to

despatch my

cablegrams from Half Moon Bay until an hour previously arranged, and in

the

meantime we revelled in the warm sand on the beach, bathed in the sea,

and

climbed amongst the trees. We lit a fire and made tea on the beach, and

while

we were having our meal the wekas, the remarkable flightless birds

found only

in New Zealand, came out from the bush for their share of the good

things.

These quaint birds, with their long bills, brown plumage and quick,

inquisitive

eyes, have no fear of men, and their friendliness seemed to us like a

welcome

from that sunny land that had always treated us with such open-hearted

kindliness. The clear, musical notes of other birds came to us from the

trees,

and we felt that we needed only good news from home to make our

happiness and

contentment absolutely complete. One of the scientific men found a cave

showing

signs of native occupation in some period of the past, and was

fortunate enough

to discover a stone adze made of the rare pounamu, or greenstone. Early next

morning we hove up the

anchor, and at 10 A.M. we entered Half Moon Bay. I went ashore to

despatch my

cablegrams, and it was strange to see new faces on the wharf after

fifteen

months during which we had met no one outside the oircle of our own

little

party. There were girls on the wharf, too, and every one was glad to

see us in

the hearty New Zealand way. I despatched my cablegrams from the little

office,

and then went on board again and ordered the course to be set for

Lyttelton,

the port from which we had sailed on the first day of the previous

year. We

arrived there on March 25 late in the afternoon. The people of

New Zealand would have

welcomed us, I think, whatever had been the result of our efforts, for

their

keen interest in Antarctic exploration has never faltered since the

early days

of the Discovery expedition, and

their attitude towards us was always that of warm personal friendship.

But the

news of the measure of success we had achieved had been published in

London and

flashed back to the southern countries, and we were met out in the

harbour and

on the wharves by oheering crowds. Enthusiastic friends boarded the Nimrod almost as soon as she entered the

heads, and when our little vessel came alongside the quay, the crowd on

deck

became so great that movement was almost impossible. Then I was handed

great

bundles of letters and cablegrams. The loved ones at home were well,

the world was

pleased with our work, and it seemed as though nothing but happiness

could ever

enter life again.  THE SPECIAL SURCHARGED EXPEDITIOR STAMP, WITH POSTMARK

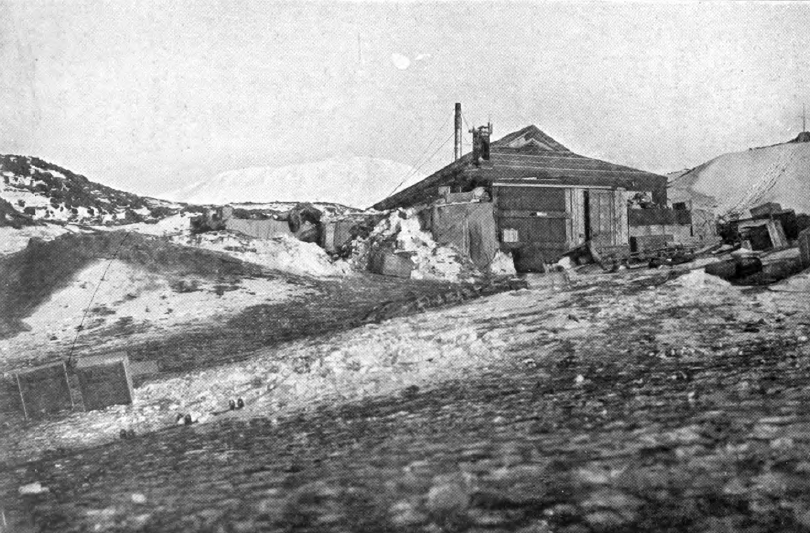

A VIEW OF THE HUT IN SUMMER. THE METEOROLOGICAL STATION CAN BE SEEN ON THE EXTREME RIGHT |