| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XXII EXTRACTS FROM THE NARRATIVE OF PROFESSOR DAVID Final Instructions: Loss of a Cooker: Camp at Butter Point: Travel. ling over Sea-ice heavy Relay-work: Cooking with Blubber: Seal Bouillon: Drygalski Glacier: Depot laid: Preparations for Trek inland: Depot at Mount Larsen New Year's Day in Latitude 74° 18': Arrival at Magnetic Pole (mean position of) January 16, 1909, 72° 25' S., 155° 16' E.: Union Jack hoisted at 3.30 P.M. THE final

instructions for the

journey of the Northern Party were read over to me in the presence of

Mawson

and Dr. Mackay, at Cape Royds on September 19, 1908. They were as

follows: "BRITISH

ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION,

1907.

"CAPE ROYDS, September 19, 1908. "You will leave

winter quarters

on or about October 1, 1908. The main objects of your journey are to be

as

follows: "(1) To take

magnetic

observations at every suitable point with a view of determining the dip

and the

position of the Magnetic Pole. If time permits, and your equipment and

supplies

are sufficient, you will try and reach the Magnetic Pole. "(2) To make a

general

geological survey of the coast of Victoria Land. In connection with

this work

you will not sacrifice the time that might be used to carry out the

work noted

in paragraph (1). It is unnecessary for me to describe or instruct you

as to

details re this work, as you know so much better than I do what is

requisite. "(3) I

particularly wish you to

be able to work at the geology of the western mountains, and for Mawson

to

spend at least one fortnight at Dry Valley to prospect for minerals of

economic, value on your return from the north, and for this work to be

carried

out satisfactorily you should return to Dry Valley not later than the

first

week of January. I do not wish to limit you to an exact date for return

to Dry

Valley if you think that by lengthening your stay up north you can

reach the

Magnetic Pole, but you must not delay, if time is short, on your way

south

again to do geological work. I consider that the thorough investigation

of Dry

Valley is of supreme importance. "(4) The Nimrod

is expected in the sound about

January 15, 1909. It is quite

possible you may see her from the west. If so, you should try to

attract

attention by heliograph to winter quarters. You should choose the hours

noon to

1 P.M. to flash your signal, and if seen at winter quarters the return

signal

will be flashed to you, and the Nimrod

will steam across as far as possible to meet you and wait at the

ice-edge. If

the ship is not in, and if she is and your signals are not seen, you

will take

into account your supply of provisions and proceed either to Glacier

Tongue or

Hut Point to replenish if there is not a sufficient amount of provision

at

Butter Point for you. "(5) Re

Butter Point. I will have a depot of

at least fourteen days'

food and oil cached there for you. If there is not enough in that

supply you

ought to return as mentioned in paragraph (4). "(6) I shall

leave instructions

for the master of the Nimrod to

proceed to the most accessible point at the west coast and there ship

all your

specimens. But before doing this, he must ship all the stores that are

lying at

winter quarters, and also keep in touch with the fast ice to the south

on the

look-out for the southern sledge-party. The Southern Party will not be

expected

before February 1, so if the ship arrives in good time you may have all

your

work done before our arrival from the south. "(7) If by

February 1, after

the arrival of the Nimrod, there is

no evidence that your party has returned, the Nimrod

will proceed north along the coast, keeping as close to the

land as possible, on the look-out for a signal from you flashed by

heliograph.

The vessel will proceed very slowly. The ship will not go north of Cape

Washington. This is a safeguard in event of any accident occurring to

your

party. "(8) I have

acquainted both

Mawson and Mackay with the main facts of the proposed journey. In the

event of

any accident happening to you, Mawson is to be in charge of the party. "(9) Trusting

that you will

have a successful journey and a safe return. "I

am, yours

faithfully, "(Sgd.) ERNEST

H. SHACKLETON,

"Commander. "PROFESSOR

DAVID,

"CAPE ROYDS, "ANTARCTIC." "CAPE

ROYDS, "BRITISH

ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION, September 20, 1907. "PROFESSOR

DAVID. "DEAR Sir, If

you reach the

Magnetic Pole, you will hoist the Union Jack on the spot, and take

possession of

it on behalf of the above expedition for the British nation. "When you are

in the western

mountains, please do the same at one place, taking possession of

Victoria Land

as part of the British Empire. "If economic

minerals are

found, take possession of the area in the same way on my behalf as

Commander of

this expedition." "Yours

faithfully, "(Sgd.)

ERNEST

H. SHACKLETON, "Commander." We had a

farewell dinner that night. The following

day, September 20, a

strong south-easterly blizzard was blowing. In the afternoon the wind

somewhat

moderated, and there was less drift. Mackay had been making a sail for

our

journey to the Magnetic Pole, and we now tried the sail on two sledges

lashed

together on the ice at Backdoor Bay. We used the tent poles of one of

the

sledging-tents as a mast. The wind was blowing very strongly and

carried off

the two sledges with a weight on them of 300 lb., in addition to the

weights of

Mackay and myself. We considered this a successful experiment. The weather

continued bad till the

night of the 24th. On September 25

we were up at 5.30 A.M.,

and found that the blizzard had subsided. Priestley, Day, and I started

in the

motor-car, dragging behind us two sledges over the sea ice. One sledge,

with

its load, weighed 606 lb.; the other weighed 260 lb. At*first Day

travelled on

his first gear; he then found that the engine became heated, and we had

to stop

for it to cool down. He discovered while we were waiting that one of

the

cylinders was not firing. This he soon fixed up all right. He then

remounted

the car and he put her on to the second gear. With the increased power

given by

the repaired cylinder we now sped over the floe-ice at fourteen miles

an hour,

much to the admiration of the seals and penguins. When, however, we had

travelled

about ten miles from winter quarters, and were some five miles westerly

from

Tent Island, we encountered numerous sastrugi of softish snow, the car

continually sticking fast in the ridges. A little low drift was flying

over the

ice surface, brought up by a gentle blizzard. We left the heavy sledge

ten

miles out, and then with only the light sledge to draw behind us, Day

found

that he was able to travel on his third gear at eighteen miles an hour.

At this

speed the sledge, whenever it took one of the snow sastrugi at right

angles,

leapt into the air like a flying fish and came down with a bump on the

surface

of the ice. We had just reached Flagstaff Point, and were taking a turn

in

towards the shore opposite the Penguin Rookery when the blizzard wind

caught

the side of the sledge nearly broadside on, and capsized it heavily. So

violent

was the shock that the aluminium cooking apparatus was knocked out of

its

straps, and the blizzard wind immediately started trundling this metal

cylinder

over the smooth ice. Day stopped his car as soon as possible, Priestley

and I

jumped off, and immediately gave chase to the runaway cooker.'

Meanwhile, the

cooker had fallen to pieces, so to speak; the tray part came away from

the big

circular cover; the melter and the supports for the cooking-pot and for

the

main outer covering also came adrift as well as the cooking-pot itself.

The lid

of the last-mentioned fell off, and immediately dumped on to the ice

the three

pannikins and our three spoons. These articles raced one after another

over the

smooth ice-surface in the direotion of the open water of Ross Sea. The

spoons

were easily captured, as also were the pannikins, but the large

snow-melter,

the main outer casing, and the tray kept revolving in front of us at a

speed which

was just sufficient to outclass our own most desperate efforts.

Finally, when

we were nearly upon them, they took a joyous leap over the low cliff of

floe-ice and disappeared one after another most exasperatingly in the

black

waters of Ross Sea. This was a shrewd loss, as aluminium cookers were,

of

course, very scarce. The following

day we had intended

laying out our second depot, but as some of the piston rings of the

motor-car

needed repair, we decided to postpone the departure until the day

after. That

afternoon, after the repairs had been completed, Day and Armytage went

out for

a little tobogganning before dinner. Late in the evening Armytage

returned

dragging slowly and painfully a sledge bearing the recumbent, though

not

inanimate, form of Day. We crowded round to inquire what was the

matter, and

found that just when Armytage and Day were urging their wild career

down a

steep snow slope Day's foot had struck an unyielding block of kenyte

lava, and

the consequence had been very awkward for the foot. As no one but Day

could be

trusted to drive the motor-car, this accident necessitated a further

postponement of the laying of our second depot. On October 3,

the weather having

cleared, Day, Priestley, Mackay, and I started with two sledges to lay

our second

depot. All went well for about eight miles out, then the carburetter

played up.

Possibly there was some dirt in the nozzle. Day took it all to pieces

in the

cold wind, and spent three-quarters of an hour fixing it up. We then

started

off again gaily in good style. We crossed a large crack in the sea ice

where

there were numbers of seals and Emperor penguins. On the other side of

this

crack our wheels stuck fast in snow sastrugi. All hands got on to the

spokes

and started swinging the car backwards and forwards; when we got a good

swing

on, Day would suddenly snatch on the power and over we would go that

is, over

one of the sastrugi only to find, often, that we had just floundered

into

another one ahead. In performing one of these evolutions Priestley,

who, as

usual, was working like a Trojan, got his hand rather badly damaged

through its

being jammed between the spokes of the car wheel and the framework.

Almost

immediately afterwards one of my fingers was nearly broken, through the

same

cause, the flesh being torn off one of my knuckles; and then Mackay

seriously

damaged his wrist in manipulating what Joyce called the

"thumb-breaking"

starter. Still we went floundering along over the sastrugi and ice

cracks, Day

every now and then getting out to lighten the car and limping

alongside. At

last we succeeded in reaching a spot amongst the snow sastrugi on the

sea ice,

fifteen miles distant from our winter quarters. Here we dumped the load

intended for the Northern Party, and then Day had a hard struggle to

extricate

the car from the tangle of sastrugi and ice-cracks. At last, after two

capsizes

of the sledges,we got back into camp at 10 P.M., all thoroughly

exhausted, all

wounded and bandaged. Brocklehurst carried Day on his back for about a

quarter

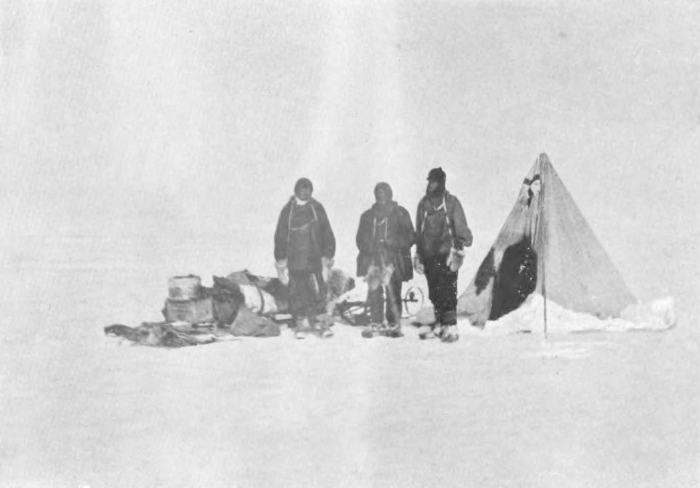

of a mile from where we left the ear up to our winter quarters.  THE MOTOR HAULING STORES FOR A DEPOT October

4 was a

Sunday, and after

the morning service we took the ponies out for exercise. In the evening

the

gramophone discoursed appropriate music, concluding with the universal

favourite, "Lead, Kindly Light." Meanwhile,

Mackay had his damaged

wrist attended to. and I put the question to him as to whether or not

he was

prepared to undertake the long journey to the Magnetic Pole under the

circumstances. He said that he was quite ready, provided Mawson and I

did not

object to his going with his wrist damaged and in a sling. We raised no

objection, and so the matter was settled. All that night Mawson and I

were

occupied in writing final letters and packing little odds and ends. The following

morning, October 5,

after an early breakfast, we prepared for the final start. Brocklehurst

took a

photograph of us just before we started, then Day, Priestley, Roberts,

Mackay,

Mawson and I got aboard, some on the motor-car, some on the sledges.

Those

remaining behind gave us three cheers, Day turned on the power, and

away we

went. A light wind was blowing from the south-east at the time of our

start,

bringing a little snow with it and another blizzard seemed impending. After

travelling a little over two

miles, just beyond Cape Barre, the snow had become so thick that the

coast-line

was almost entirely hidden from our view. Under these circumstances I

did not

think it prudent to take the motor-car further, so Mackay, Mawson, and

I bid

adieu to our good friends. Strapping on our harness, we toggled on to

the

sledge rope, and with a "One, two, three" and "away,"

started on our long journey over the sea ice. We reached our

ten-mile depot about

7 P.M. and got up our tent. We slept that night on the floe-ice, with

about

three hundred fathoms of water under our pillow. The following

morning, October 6, we

started our relay work. We dragged the Christmas Tree sledge on first,

as we

were specially liable to lose parcels off it, for a distance of from

one-third

to half a mile. Then we returned and fetched up what we called the Plum

Duff

sledge, chiefly laden with our provisions. The weather may be described

as

thick, with snow falling ab intervals. We camped that night amongst

screw

pack-ice within less than a mile of our fifteen-mile depot. The following

day, October 7, was

beautifully fine and calm. We started

about 9 A.M. and sledged

over pressure ice ridges and snow sastrugi, reaching our fifteen-mile

depot in

three-quarters of an hour. Here we camped and repacked our sledges. We

took the

wholemeal plasmon biscuits out of two of the biscuit tins and packed

them into

canvas bags. This saved us a weight of about 8 lb. We started

again in the afternoon,

relaying with the two sledges. The sledging again was heavy on account

of the

fresh, soft snow, and small sastrugi. We had a glorious view of the

western

mountains, crimsoned in the light of the setting sun. We camped that

night

close to a seal hole which belonged to a fine specimen of Weddell seal.

We were

somewhat disturbed that night by the snorting and whistling of the

seals as

they came up for their blows. . . . On October 10,

we were awakened by

the chatter of some Emperor penguins who had marched down on our tent

during

the night to investigate us. The sounds may be described as something

between

the cackle of a goose and the chortle of a kookaburra. On peeping out

of the

Burberry spout of our tent I saw four standing by the sledges. They

were much

interested at the sight of me, and the conversation between them became

lively.

They evidently took us for penguins of an inferior type, and the tent

for our

nest. They watched, and took careful note of all our doings, and gave

us a good

send-off when we started about 8.30 A.M. The sky was overcast, and

light snow

began to fall in the afternoon. A little later a mild blizzard sprang

up from

the south-east; we thought this a favourable opportunity for testing

the

sailing qualities of our sledges, and so made sail on the Plum Duff

sledge. As

Mackay put it, we "brought her to try with main course." As the

strength of the blizzard increased, we found that we could draw both

sledges

simultaneously, which was, of course, a great saving in labour. We were

tempted

to carry on in the increasing strength of the blizzard rather longer

than was

wise, and consequently, when at last we decided that we must camp, had

great

difficulty in getting the tent up. We slipped the tent over the poles

placed

close to the ground in the lee of a sledge. While two of us raised the

poles,

the third shovelled snow on to the skirt of the tent, which we pulled

out

little by little, until it was finally spread to its full dimensions.

We were

glad to turn in and escape from the biting blast and drifting snow. Sunday,

October

11. A

violent

blizzard was still blowing, and we lay in our sleeping-bag

until past noon, by which time the snow had drifted high upon the door

side of

our tent. As this drift was pressing heavily on our feet and cramping

us, I got

up and dug it away. The cooker and primus were then brought in and we

all got

up and had some hoosh and tea. The temperature, as usually happens in a

blizzard, had now risen considerably, being 8.5° Fahr. at 1.30 P.M. The

copper

wire on our sledges was polished and burnished by the prolonged blast

against

it of tiny ice crystals, and the surface of the sea ice was also

brightly

polished in places. As it was still blowing we remained in our

sleeping-bag for

the rest of that day as well as the succeeding night. When we rose at

about 2 A.M. on

Monday, October 12, the blizzard was over. We found very heavy

snow-drifts on

the lee side of our sledges, and it took us a considerable time to dig

these

away and get the hard snow raked out of all the chinks and crannies

among the

packages on the sledges. We made a start about 4 A.M., and all that day

meandered amongst broken pack-ice. It was evident that the south-east

blizzards

drive large belts of broken floe-ice in this direction across McMurdo

Sound to

the western shore. The fractured masses of sea ice, inclined at all

angles to

the horizontal, are frozen in later, as the cold of winter becomes more

intense, and, of course, constitute a very difficult surface for

sledging. October 13.

We camped at the foot of a low ice cliff, about 600 yards

south-south-east of

Butter Point. Butter Point is merely an angle in this low ice-cliff

near the

junction of the Ferrar Glacier valley with the main shore of Victoria

Land.

This cliff was from fifteen to twenty feet in height, and formed of

crevassed

glacier ice. During part of

this day Mawson and

Mackay were busy making a mast and boom for the second sledge, it being

our

intention to use the tent floorcloth as a sail. Meanwhile I sorted out

the

material to be left at the depot at Butter Point. The following

day, Wednesday,

October 14, we spent the morning in resorting the loads on our sledges.

We

depoted two tins of wholemeal plasmon biscuits, each weighing about 27

lb.,

also Mackay's mountaineering nail boots, and my spare head-gear

material and

mits. Altogether we lightened the load by about 70 lb. We sunk the two

full

tins of biscuits and a tin containing boots, &c., a short

distance in the

glacier ice to prevent the blizzards blowing them away. We then lashed

to the

tins a short bamboo flag-pole, carrying one of our black depot flags,

and

securely fastened to its base one of our empty air-tight milk tins, in

which we

placed our letters. In these letters for Lieutenant Shackleton and R.

E.

Priestley respectively, I stated that in consequence of our late start

from

Cape Royds, and also on account of the comparative slowness of our

progress

thence to Butter Point, it was obvious that we could not return to

Butter Point

until January 12, at the earliest, instead of the first week of

January, as was

originally anticipated. We ascertained months later that this little

depot

survived the blizzards, and that Armytage, Priestley, and Brocklehurst

had no

difficulty in finding it, and that they had read our letters. October 14.

Leaving the depot about 9 A.M., we started sledging across New Harbour

in the

direction of Cape Bernacchi. In the afternoon a light southerly wind

sprang up

bringing a little snow with it, the fall lasting from about 12.30 to

2.30 P.M.

We steered in the direction of what appeared to us to be an uncharted

island.

On arriving at it, however, we discovered that it was a true iceberg,

formed of

hard blue glacier ice with a conspicuous black band near its summit

formed of

fine dark gravel. The iceberg was about a quarter of a mile in length,

and

thirty to forty feet high. October 15.

We had a glorious view up the valley of the Perm Glacier. The cold was

now less

severe; at 8 P.M. the temperature was 9.5° Fahr. October 16.

We were up at 3.30 A.M., and got under way at 5.30. A cold wind was

blowing

from the south, and after some trouble we set sail on both sledges,

using the

green floorcloth on the Christmas Tree sledge, and Mackay's sail on the

Plum

Duff sledge. A short time after we set sail it fell nearly calm; thick

clouds

gathered; a light wind sprang up from the south-east, veering to

east-north-east, then back again to south-east in the afternoon. Fine

snow fell

for about three hours, forming a layer nearly a quarter of an inch in

thickness. Towards evening we reached one of the bergs that had been

miraged up

the night before. It was four hundred yards long, and eighty yards

wide, and

was a true iceberg formed of glacier ice; Mackay, Mawson, and I

explored this.

Like the previous iceberg, its surface was pitted with numerous deep

dust

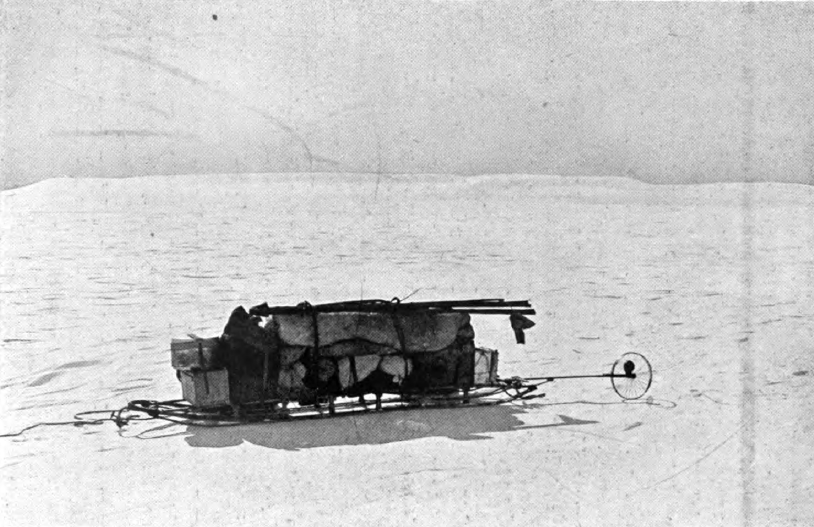

wells.  LOADED SLEDGE SHOWING THE DISTANCE RECORDER OR SLEDGEMETER As

the shore

was high and rocky, and

seemed not more than half a mile distant, I went over towards it after

our

evening meal. On the way, for the first time, I met with a structure in

the sea

ice known as pancake ice. The surface of the ice showed a rounded

polygonal

structure something like the tops of a number of large weathered

basaltic

columns. The edges of these polygons were slightly raised, but

sufficiently

rounded off by thawing or ablation to afford an easy surface for the

runners of

our sledge. Close in shore the pancake ice was traversed by deep tidal

cracks. October 17.

Mawson, Mackay, and I landed at Cape Bernacchi, a little over a mile

north of

our previous camp. Here we hoisted the Union Jack just before 10 A.M.

and took

possession of Victoria Land for the British Empire. Cape Bernacchi is a

low

rocky promontory, the geology of which is extremely interesting. The

dominant

type of rock is a pure white coarsely crystalline marble; this has been

broken

through by granite rocks, the latter in places containing small red

garnets.

After taking possession we resumed our sledging, finding the surface of

pancake

ice very good. October 18.

We reached an interesting headland to-day about one and a quarter miles

from

our preceding camp. The rocks bore a general resemblance to those at

Cape

Bernacchi. Mawson thought that some of the quartz veins traversing this

headland would prove to be auriferous. After leaving this Point the

wind freshened

considerably. We had previously hoisted sail, and the wind was

sufficiently

strong to admit of our pulling both sledges together. The total

distance

travelled was seven statute miles. This was the most favourable wind we

experienced during the whole of our journey to and from the Magnetic

Pole. That night I

experienced a rather

bad attack of snow blindness through neglecting to wear my snow-goggles

regularly. Finding that my eyes were no better next morning, and my

sight being

dim I asked Mawson to take my place at the end of the long rope, the

foremost

position in the team. Mawson proved himself on this occasion and

afterwards so

remarkably efficient at picking out the best track for our sledges, and

steering a good course, that at my request he occupied this position

throughout

the rest of the journey. The next two

days were uneventful,

except for the fact that we occasionally had extremely heavy sledging

over

screw pack-ice and high and long sastrugi. On the night of

October 20, we

camped on the sea ice about three-quarters of a mile off shore. To the

north-east of us was an outward curve of the shore-line, shown as a

promontory

on the existing chart. Early the next morning I walked over to the

shore to

geologise, and found the rocky headland composed of curious gneissic

granite

veined with quartz. On ascending this headland I noticed to my surprise

that

what had been previously supposed to be a promontory was really an

island

separated by a narrow strait from the mainland. While Mawson

determined the position

of this island by taking a round of angles with the theodolite, Mackay

and I

crossed the strait and explored the island, pacing and taking levels.

The rocks

of which the erratics and boulder-bearing gravels were formed were

almost

without exception of igneous origin. One very interesting exception was

a block

of weathered clayey limestone. This was soft and yellowish grey

externally, but

hard and blue on the freshly fractured surfaces inside. It contained

traces of

small fossils which appeared to be seeds of plants. Two chips of this

rock were

fortunately preserved, sufficient for ehemical analysis and microscopic

examination. There could be little doubt that this clayey limestone has

been

derived from the great sedimentary formation, named by H. T. Ferrar,

the Beacon

sandstone. The island which we had been exploring we named

provisionally

Terrace Island. It was approximately triangular in shape, and the side

facing

the strait, down which we travelled, measured one mile 1200 yards in

length. October 23.

To-day we held a serious council as to the future of our journey

towards the

Magnetic Pole. It was quite obvious that at out present rate of

travelling,

about four statute miles daily by the relay method, we could not get to

the

Pole and return to Butter Point early in January. I suggested that the

most

likely means of getting to the Pole and back in the time specified by

Lieutenant Shackleton would be to travel on half- rations, depoting the

remainder of our provisions at an early opportunity. Mawson and Mackay

agreed,

after some discussion, to try this expedient, and we decided to think

the

matter over for a few days and then make our depot. October 24.

We reached in the evening a long rocky point of gneissic granite, which

we

called Gneiss Point. After our evening hoosh we walked across to the

point and

collected a number of interesting geological specimens, including

blocks of

kenyte lava. October 25

proved a very heavy day

for sledging, as we had to drag the sledges over new snow from three to

four

inches deep. In places it had a tough top crust which we would break

through up

to our ankles We met also several obstacles in the way of wide cracks

in the

sea ice, from six to ten feet in width, and several miles in length.

The sea

water between the walls of the cracks had only recently been frozen

over, so

that the ice was only just thick enough to bear the sledges. In pursuing our

north-westerly

course we were now crossing a magnificent bay, which trended westwards

some

five or six miles away from the course we were steering. On either side

of this

bay were majestic ranges of rocky mountains parted from one another at

the head

of the bay by an immense glacier with steep ice falls. On examining

these

mountains with a field-glass it was evident that in their lower

portions they

were formed of granite and gneiss, producing reddish brown soils. At

the higher

levels, further inland, there were distinct traces of rocks showing

horizontal

stratification. The highest rock of all was black in colour, and

evidently very

hard, apparently some three hundred feet in thickness. Below this was

some

softer stratified formation, approximately one thousand feet in

thickness. We

concluded that the hard top layer was composed of igneous rock,

possibly a

lava, while the horizontal stratified formation belonged in all

probability to

the Beacon sandstone formation. Some fine nunataks of dark rock rose

from the

south-east side of the great glacier. On either side of this glacier

were high

terraces of rock reaching back for several miles from a modern valley

edge to

the foot of still higher ranges. It was obvious that these terraces

marked the

position of the floor of the old valley at a time when the glacier ice

was

several thousand feet higher than it is now, and some ten miles wider

than at

present. The glacier trended inland in a general south-westerly

direction. We longed to

turn our sledges

shorewards and explore these inland rocks, but this would have involved

a delay

of several days probably a week at least and we could not afford

the time.

Mawson took a series of horizontal and vertical angles with the

theodolite to

all the upper peaks in these ranges. We were much puzzled to determine

on what

part of the charted coast this wide bay and great glacier valley was

situated.

We found out much later that the point opposite which we had now

arrived was in

reality Granite Harbour, and that its position was not shown correctly

on the

chart. October 27.

The weather was beautifully clear and sunshiny, and we had a glorious

view of

the great mountain ranges on either side of Granite Harbour. The rich

colouring

of warm sepia brown and terra-cotta in these rocky hills was quite a

relief to

the eye. Wind springing up in the south-east, we made sail on both

sledges, and

this helped us a good deal over the soft snow and occasional patches of

sharp-edged brash ice. Towards evening

we fetched up

against some high ice-pressure cracks with the ice ridged up six to

eight feet

high in huge tumbled blocks. We seemed to have got into a labyrinth of

these

pressure ridges from which there was no outlet. At last, after several

capsizes

of the sledges and some chopping through the ice ridges by Mackay, we

got the

sledges through, and camped on a level piece of ice. Mawson and I at

this time were

still wearing finnesko, while Mackay had taken to ski boots. October 28.

The sledging was again very heavy over sticky, soft snow alternating

with hard

sastrugi and patches of consolidated brash ice. After our evening

hoosh, Mawson

and I went over to the shore, rather more than half a mile distant, in

order to

study the rocks. These we found were composed of coarse red granite;

the top of

the granite was much smoothed by glacier ice, and strewn with large

erratic

blocks. In places the granite was intersected by black dykes of basic

rocks.

One could see that the glacier ice, about a quarter of a mile inland

from this

rocky shore, had only recently retreated and laid bare the glaciated

rocky

surface. We found a little moss here amongst the crevices in the

granite rock. October 29 was

beautifully fine,

though a keen and fresh wind, rather unpleasantly cold, was blowing

from off

the high mountain plateau to our west. We were all thoroughly done up

at night

after completing our four miles of relay work. That evening we

discussed the

important question of whether it would be possible to eke out our

food-supplies

with seal meat so as to avoid putting ourselves on half-rations, and we

all

agreed that this should be done. We made up our minds that at the first

convenient

spot we would make a depot of any articles of equipment, geological

specimens,

&c., in order to lighten our sledges, and would at the same

time, if the

spot was suitable, make some experiments with seal meat. The chief

problem in

connection with the latter was how to cook it without the aid of

paraffin oil,

as we could not afford paraffin for this purpose. October 30 was

full of interest for

us, as well as hard work. In the early morning, between 2.30 A.M. and

6.30 A.M.,

a mild blizzard was blowing. We got under way a little later and camped

at

about 10.30 A.M. for lunch alongside a very interesting rocky point.

Mawson got

a good set of theodolite angles from the top of this point. We tried, on

that day, the

experiment of strengthening the brew of the tea by using the old

tea-leaves of

a previous meal mixed with the new ones. This was Mackay's idea, and

Mawson and

I at the time did not appreciate the experiment. Later on, however, we

were

very glad to adopt it. The weather was

now daily becoming warmer

and the saline snow on the sea ice became sticky in consequence. It

gripped the

runners of the sledges like glue, and we were only able with our

greatest

efforts to drag the sledges over this at a snail's pace. We were all

thoroughly

exhausted that evening when we camped at the base of a rocky promontory

about

180 ft. high. This cliff was formed of coarse gneiss, with numerous

dark

streaks, and enclosures of huge masses of greenish-grey quartzite.

After our

evening hooch we walked over to a very interesting small island about

three-quarters of a mile distant. It was truly a most wonderful place

geologically, and was a perfect elysium for the mineralogist. The

island, which

we afterwards called Depot Island, was accessible on the shoreward

side, but rose

perpendicularly to a height of 200 ft. above sea-level on the other

three

sides. There was very little snow or ice upon it, the surface being

almost

entirely formed of gneissic granite. This granite was full of dark

enclosures

of basic rooks, rich in black mica and huge crystals of hornblende. It

was in

these enclosures that Mawson discovered a translucent brown mineral,

which he

believed to be monazite, but which has since proved to be titanium

mineral. October 31.

We packed up and made for the island at 9.30 A.M. The sledging was

extremely

heavy, and we fell into a tide-crack on the way, but the sledge was got

over

safely. Mackay sighted a seal about six hundred yards distant from the

site of

our new camp near the island, and just then, we noticed that another

seal had

bobbed up in the tide-crack close to our old camp. Mackay and Mawson at

once

started off in the direction where the first seal had been sighted. It

proved

to be a bull seal in very good condition, and they killed it by

knocking it on

the head with an ice-axe. Meanwhile, I unpacked the Duff sledge and

took it out

to them. Returning to the site of our camp I put up the tent, and on

going back

to Mawson and Mackay found that they had finished fletching the seal.

We loaded

up the empty sledge with seal blubber, resembling bars of soap in its

now

frozen condition, steak and liver, and returned to camp for lunch. After lunch we

took some blubber and

seal meat on to the island, intending to try the experiment of making a

blubber

fire in order to cook the meat. We worked our way a short distance up a

steep,

rocky gully, and there built a fireplace out of magnificent specimens

of

hornblende rock. It seemed a base use for such magnificent

mineralogical

specimens, but necessity knows no laws. We had brought with us our

primus lamp

in order to start the fire. We put blubber on our iron shovel, warmed

this

underneath by means of the heat of the primus lamp so as to render down

the oil

from it, and then lit the oil. The experiment was not altogether

successful.

Mawson cooked for about three hours, closely and anxiously watched by

Mackay

and myself. Occasionally he allowed us to taste small snacks of the

partly

cooked seal meat, which were pronounced to be delicious. While the

experiment was at its most

critical stage, at about 6 P.M., we observed sudden swirls of snowdrift

high up

on the western mountains, coming rapidly to lower levels. For a few

minutes we

did not think seriously of the phenomenon, but as the drift came nearer

we saw

that something serious was in the air. Mackay and I rushed down to our

tent,

the skirt of which was only temporarily secured with light blocks of

snow. We

reached it just as it was struck by the sudden blizzard which had

descended

from the western mountains. There was no time to dig further blocks of

snow,

all we could do was to seize the heavy food-bags on our sledges,

weighing sixty

pounds each, and rush them on to the skirt of the tent. The blizzard

struck our

kitchen on the island simultaneously with our tent, and temporarily

Mawson lost

his mite and most of the tit-bits of seal meat, but these were quickly

recovered, and he came rushing down to join us in securing the tent.

While

Mawson in frantic haste chopped out blocks of snow and dumped them on

to the

skirt of the tent, Mackay, no less frantically, struggled with our

sleeping-bag, which had been turned inside-out to air, and which by

this time

was covered with drift snow. He quickly had it turned right side in

again, and

dashed it inside the tent. At last everything was secured, and we found

ourselves safe and sound inside the tent. On November 1

we breakfasted off a

mixture of our ordinary hoosh and seal meat. After some discussion we

decided

that our only hope of reaching the Magnetic Pole lay in our travelling

on half-rations

from our present camp to the point on the coast at the Drygalski

Glacier, where

we might for the first time hope to be able to turn inland with

reasonable

prospect of reaching the Magnetic Pole. Mawson was emphatic that we

must

conserve six weeks of full rations for our inland journey to and from

the Pole.

This necessitated our going on half-rations from this island to the far

side of

the Drygalski Glacier, a distance of about one hundred statute miles.

In order

to supplement the regular hall-rations we intended to take seal meat. While I was

busy in calculating the

times and distances for the remainder of our journey, and proportioning

the

food rations to suit our new programme, Mawson and Mackay conducted

further

experiments on the cooking of seal meat with blubber. While at our

winter

quarters, Mackay had made some experiments on the use of blubber as a

fuel. He

had constructed a blubber lamp, the wick of which kept alight for

several hours

at a time, feeding itself on the seal oil. He had tried the experiment

of

heating up water over this blubber lamp, and was partly successful at

the time

when we left winter quarters for our present sledging journey. But his

experiments at the time were not taken very seriously, and the blubber

lamp was

left behind, a fact which we now much regretted. An effective

cooking-stove

was, however, evolved, as the result of a series of experiments this

day, out

of one of our large empty biscuit tins. The lid of this was perforated

with a

number of circular holes for the reception of wicks. Its edges were

bent down,

so as to form supports to keep the wick-holder about half an inch above

the

bottom of the biscuit tin. The wick-holder was put in place; wicks were

made of

pieces of old calico food-bags rolled in seal blubber, or with thin

slices of

seal blubber enfolded in them, the calico being done up in little rolls

for the

purpose of making wicks, as one rolls a cigarette, the seal blubber

taking the

place of the tobacco in this case. Lumps of blubber were laid round the

wick-holder. Then, after some difficulty, the wicks were lighted. They

burned

feebly at first, as seal blubber has a good deal of water in it. After

some

minutes of fitful spluttering, the wicks got fairly alight, and as soon

as the

lower part of the biscuit tin was raised to a high temperature, the big

lumps

of blubber at the side commenced to have the water boiled out of them

and the

oil rendered down. This oil ran under the wick-holder and supplied the

wicks at

their base. The wicks, now fed with warm, pure seal-oil, started to

burn

brightly, and even fiercely, so that it became necessary occasionally

to damp

them down with chips of fresh blubber. We tried the experiment of using

lumps

of salt as wicks, and found this fairly successful, but we decided to

rely for

wicks chiefly on our empty food-bags, and thought possibly that if

these ran

out we might have recourse to moss. But the empty food-bags supplied

sufficient

wick for our need. That day, by

means of galvanised

iron wires, we slung the inner pot from our aluminium cooker over the

lighted

wicks of our blubber cooker, thawed down snow in it, added chips of

seal meat

and made a delicious bouillon. This had a rich red colour and seemed

very

nutritious, but to me was indigestible. While Mawson was still engaged

on

further cooking experiments, Mackay and I ascended to the highest point

of the

island, selected a spot for a cairn to mark our depot, and Mackay

commenced

building the cairn. Meanwhile, I returned to camp. It had, of

course, become clear to

us, in view of our experience of the already cracking sea ice near

Granite

Harbour, as well as in view of our comparatively slow progress by

relay, that

our retreat back to camp from the direction of the Magnetic Pole would

in all

probability be entirely cut off through the breaking up of the sea ice.

Under

these circumstances we determined to take the risk of the Nimrod

arriving safely on her return

voyage at Cape Royds, where

she would receive the instructions to search for us along the western

coast,

and also the risk of her not being able to find our depot and

ourselves. We

knew that there was a certain amount of danger in adopting this course,

but we

felt that we had got on so far with the work entrusted to us by our

Commander

that we could not honourably now tura back. Under these circumstances

we each

wrote farewell letters to those who were nearest and dearest, and the

following

morning, November 2, we were up at 4.30 A.M. After putting all the

letters into

one of our empty dried-milk tins, and fitting on the airtight lid, I

walked

with it to the island and climbed up to the cairn. Here, after

carefully

depoting several bags of geological specimens at the base of the

flagstaff, I

lashed the little post office by means of cord and copper-wire securely

to the

flagstaff, and then carried some large slabs of exfoliated granite to

the

cairn, and built them up on the leeward side of it in order to

strengthen it

against the southerly blizzards. A keen wind was blowing, as was usual

in the

early morning, off the high plateau, and one's hands got frequently

frost-bitten in the work of securing the tin to the flagstaff. The

cairn was at

the seaward end of a sheer oliff two hundred feet high. It was later

than usual when we

started our sledges, and the pulling proved extremely heavy. The sun's

heat was

thawing the snow surface and making it extremely sticky. Our progress

was so

painfully slow that we decided, after with great efforts doing two

miles, to

camp, have our hoosh, and then turn in for six hours, having meanwhile

started

the blubber lamp. At the expiration of that time we intended to get out

of our

sleeping-bag, breakfast, and start sledging about midnight. We hoped

that by

adopting nocturnal habits of travelling, we would avoid the sticky

ice-surface

which by daytime formed such an obstacle to our progress. We carried

out this

programme on the evening of November 2, and the morning of November 3.

We found

the experiment fairly successful, as at midnight and for a few hours

afterwards

the temperature remained sufficiently low to keep the surface of the

snow on

the sea ice moderately crisp. On November 3

and 4 the weather was

fine, and we made fair progress. On the

following day, November 5, we

were opposite a very interesting coastal panorama, some twenty miles

north of

Granite Harbour. Magnificent ranges of mountains, steep slopes free

from snow

and ice, stretched far to the north and far to the south of us, and

finished

away inland, towards the heads of long glacier-out valleys, in a vast

upland

snow plateau. The rocks which were exposed to view in the lower part of

these

ranges were mostly of warm sepia brown to terra-cotta tint, and were

evidently

built up of a continuation of the gneissic rocks and red granites which

we had

previously seen. Above these crystalline rocks came a belt of

greenish-grey

rock, apparently belonging to some stratified formation and possibly

many

hundreds of feet in thickness; the latter was capped with a black rock

that

seemed to be either a basic plateau lava or a huge sill. In the

direction of

the glacier valleys, the plateau was broken up into a vast number of

conical

hills of various shapes and heights, all showing evidence of intense

glacial

action in the past. The hills were here separated from the coast-line

by a

continuous belt of piedmont glacier ice. This last terminated where it

joined

the sea ice in a steep slope, or low cliff, and in places was very much

crevassed. Mawson, at our noon halt for lunch,. continued taking the

angles of

all these ranges and valleys with our theodolite. The temperature

was now rising,

being as high as 22° Fahr. at noon on November 5. We had a very heavy

sledging

surface that day, there being much consolidated brash ice, sastrugi,

pie-crust

snow, and numerous cracks in the sea ice: As an offset to these

troubles we had

that night, for the first time, the use of our new frying-pan,

constructed by

Mawson out of one of our empty paraffin tins. This tin had been cut in

half

down the middle parallel to its broad surfaces, and loops of iron wire

being

added, it was possible to suspend it inside the empty biscuit tin above

the

wicks of our blubber lamp. We found that in this frying-pan we could

rapidly

render down the seat blubber into oil, and as soon as the oil boiled we

dropped

into the pan small slices of seal liver or seal meat. The liver took

about ten

minutes to cook in the boiling oil, the seal meat about twenty minutes.

These

facts were ascertained by the empirical method. Mawson discovered by

the same

method that the nicely browned and crisp residue from the seal blubber,

after

the oil in it had become rendered down, was good eating, and had a fine

nutty

flavour. We also found, as the result of later experiments, that

dropping a

little seal's blood into the boiling oil produced eventually a gravy of

very

fine flavour. If the seal's blood was poured in rapidly into the

boiling oil,

it made a kind of gravy pancake, which we also considered very good as

a

variety. We had a

magnificent view this day

of fresh ranges of mounrains to the north of Der ot Island. At the foot

of

these was an extensive terrace of glacier ice, a curious type of

piedmont

glacier. Its surface was strongly convex near where it terminated

seawards in a

steep slope or low cliff. In places this ice was heavily crevassed. At

a distance

of several miles inland, it reached the spurs of an immense coastal

range,

while in the wide gaps in this range the ice trended inland as far as

the eye

could see until it blended in the far distance with the skyline high up

on the

great inland plateau. A little before

9 P.M. on November 5

we left our sleeping-bag, and found snow falling, with a fresh and

chilly

breeze from the south. The blubber lamp, which we had lighted before we

had

turned in, had got blown out. We built a chubby house for it of snow

blocks to

keep off the wind, and relighted it, and then turned into the

sleeping-bag

again while we waited for the snow and chips of seal meat in our

cooking-pot to

become converted into a hot bouillon; the latter was ready after an

interval of

about one hour and a half. Just before midnight we brought the cooker

alight

into the tent in order to protect it from the blizzard which was now

blowing

and bringing much falling snow with it. Mawson's cooking experiments

continued

to be highly successful and entirely satisfactory to the party. We waited for

the falling snow to

clear sufficiently to enable us to see a short distance ahead, awl then

started

again, the blizzard still blowing with a little low drift. After doing

a stage

of pulling on both sledges to keep ourselves warm in the blizzard we

set sail

always a chilly business and the wind was a distinct assistance to

us. We

encountered a good deal of brash ice that day, and noticed that this

type of

ice surface was most common in the vicinity of icebergs, which just

here were

very numerous. The brash ice is probably formed by the icebergs surging

to and

fro in heavy weather like a lot of gigantic Yermaks, and crunching up

the sea

ice in their vicinity. The latter, of course, re-freezes, producing a

surface

covered with jagged edges and points. We were now

reduced to one plasmon

biscuit each for breakfast and one for evening meal, and we were

unanimous in

the opinion that we had never before fully realised how very nice these

plasmon

biscuits were. We became exceedingly careful even over the crumbs. As

some

biscuits were thicker than others, the cook for the week would select

three

biscuits, place them on the outer cover of our aluminium cooker, and

get one of

his mates to look in an opposite direction while the messman pointed to

a

biscuit and said, "Whose?" The mate with averted face, or shut eyes,

would then state the owner, and the biscuit was ear-marked for him, and

so with

the other two biscuits. Grievous was the disappointment of the man to

whose lot

the thinnest of the three biscuits had fallen. Originally, on this

sledge

journey, when biscuits were more plentiful, we used to eat them

regardless of

the loss of crumbs, munching them boldly, with the result that

occasional

crumbs fell on the floor-cloth. Not so now. Each man broke his biscuit

over his

own pannikin of hoosh, so that any crumbs produced in the process of

fracture

fell into the pannikin. Then, in order to make sure that there were no

loose

fragments adhering to the morsel we were about to transfer to our

mouths, we

tapped the broken chip, as well as the biscuit from which it had been

broken,

on the sides of the pannikin, so as to shake into it any loose crumbs.

Then,

and then only, was it safe to devour the precious morsel. Mackay, who

adopted this practice in

common with the rest of us, said it reminded him of the old days when

the

sailors tapped each piece of broken biscuit before eating it in order

to shake

out the weevils. Mawson and I

now wore our ski boots

instead of finnesko, the weather being warmer, and the ski boot giving

one a

better grip on the snow surface of the sea ioe. The rough leather took

the skin

off my right heel, but Mackay fixed it up later in the evening, that

is, my

heel, with some " Newskin." We sledged on

uneventfully for the

remainder of November 6, and during the 7th, and on November 8 it came

on to

blow again with fresh-falling snow. The blizzard was still blowing when

the

time came for us to pitch our tent. We had a severe struggle to get the

tent up

in the high wind and thick falling snow. At last the work was

accomplished, and

we were all able to turn into our sleeping-bag, pretty tired, at about

12.30

P.M. The weather was

still bad the

following day, November 9. After breakfast off seal's liver, and

digging out

the sledges from the snow-drift, we started in the blizzard, the snow

still

falling. After a little while we made sail on both sledges. The light

was very

bad on account of the thick falling snow, and we were constantly

falling up to

our knees in the cracks in the sea ice. It seemed miraculous that in

spite of

these very numerous accidents we never sprained an ankle. That day we saw

a snow petrel, and

three skua gulls visited our Damp. At last the snow stopped falling and

the

wind fell light, and we were much cheered by a fine, though distant,

view of

the Nordenskjold Ice Barrier to the north of us. We were all extremely

anxious

to ascertain what sort of a surface for sledging we should meet with on

this

great glacier. According to the Admiralty chart, prepared from

observations by

the Discovery expedition, this

glacier was between twenty-four and thirty miles wide, and projected

over

twenty miles from the rocky shore into the sea. We hoped that we might

be able

to miss it without following a circuitous route along its seaward

margins. We started off

on November 10,

amongst very heavy sastrugi and ridges of broken pack-ice. Cracks in

the sea

ice were extremely numerous. The temperature was up to plus 3° Fahr. at

8 A.M.

That day when we pitched camp we were within half a mile of the

southern edge

of the Nordenskjold Ice Barrier. The following

day, November 11, as

Mawson wished to get an accurate magnetic determination with the

Lloyd-Creak

dip circle, we decided to camp, Mackay and I exploring the glacier

surface to

select a suitable track for our sledges while Mawson took his

observations.

After breakfast we removed everything containing iron several hundred

yards

away from the tent, leaving Mawson alone inside it in company with the

dip

circle. We found that the ascent from the sea ice to the Nordenskjold

Ice

Barrier was a comparatively easy one. The surface was formed chiefly of

hard

snow glazed in places, partly through thawing and re-freezing, partly

through

the polishing of this windward surface by particles of fresh snow

driven over

it by the blizzards. The surface ascended gradually to a little over

one

hundred feet above the level of the sea ice, passing into a wide

undulating

plain which stretched away to the north as far as the eye could see. We returned to

Mawson with the good

news that the Nordenskjold Ice Barrier was quite practicable for

sledging, and

would probably afford us a much more easy surface than the sea ice over

which

we had previously been passing. Mawson informed us, as the result of

his

observations with the dip circle, that the Magnetic Pole was probably

about

forty miles further inland than the theoretical mean position

calculated for it

from the magnetic observations of the Discovery

expedition seven years ago. Early on the

morning of November 12

we packed up, and started to cross the Nordenskjold Ice Barrier. We

noticed

here that there were two well-marked sets of sastrugi, one set, nearly

due

north and south, formed by the strong southerly blizzards, the other

set, crossing

nearly at right angles, coming from the west and formed by the cold

land winds

blowing off the high plateau at night on to the sea. November 12 was

an important one in

the history of Mawson's triangulation of the coast, for he was able in

the

morning to sight simultaneously Mount Erebus and Mount Melbourne, as

well as

Mount Lister. We were fortunate in having a very bright and clear day

on this

occasion, and the round of angles obtained by Mawson with the

theodolite were

in every way satisfactory. November 13. We

were still on the

Nordenskjold Ice Barrier. The temperature in the early morning, about 3

A.M.,

was minus 13° Fahr. Mawson had provided an excellent dish for breakfast

consisting of crumbed seal meat and seal's blood, which proved

delicious. We got

under way about 2 A.M. It was a beautiful sunshiny day with a gentle

cold

breeze off the western plateau. When we had sledged for about one

thousand

yards Mawson suddenly exclaimed that he could see the end of the

barrier where

it terminated in a white cliff only about six hundred yards ahead. We

halted

the sledge, and while Mawson took some more theodolite angles Mackay

and I

reconnoitred ahead but could find no way down the cliff. We returned to

the

sledge and all pulled on for another quarter of a mile. Once more we

reconnoitred, and this time both Mawson and I found some steep slopes

formed by

drifted snow which were just practicable for a light sledge lowered by

an

alpine rope. We chose what seemed to be the best of these; Mackay tied

the

alpine rope around his body, and taking his ice-axe, descended the

slope

cautiously, Mawson and I holding on to the rope meanwhile. The snow

slope

proved fairly soft, giving good foothold, and he was soon at the bottom

without

having needed any support from the alpine rope. He then returned to the

top of

the slope, and we all set to work unpacking the sledges. We made fast

one of

the sledges to the alpine rope, and after loading it lightly lowered it

little

by little down the slope, one of us guiding the sledge while the other

two

slacked out the alpine rope above. The man who went with the sledge to

the

bottom would unload it there on the sea ice and then climb up the

slope, the

other two meanwhile pulling up the empty sledge. This manoeuvre was

repeated a

number of times until eventually the whole of our food and equipment,

including

two sledges, were safely down on the sea ice below. We were all

much elated at having

got across the Nordenskjold Ice Barrier so easily and so quickly. We

were also

fortunate in securing a seal; Mackay went off and killed this, bringing

back

seal steak, liver, and a considerable quantity of seal blood. From the

last

Mackay said he intended to manufacture a black pudding. While Mackay

had been in pursuit of

the seal meat Mawson had taken a meridian altitude while I kept the

time for

him. After our hoosh we packed the sledges, and Mawson took a

photograph

showing the cliff forming the northern boundary of the Nordenskjold Ice

Barrier. This cliff was about forty feet in height. There can be little

doubt,

I think, that the greater part of this Nordenskjold Ice Barrier is

afloat. The sun was so

warm this day that I

was tempted before turning in to the sleeping-bag to take off my ski

boots and

socks and give my feet a snow bath, which was very refreshing. The following

day, November 14, we

were naturally anxious to be sure of our exact position on the chart,

in view

of the fact that we had come to the end of the ice barrier some

eighteen miles

quicker than the chart led us to anticipate. Mawson accordingly worked

up his

meridian altitude, and I plotted out the angular distances he had found

respectively, for Mount Erebus, Mount Lister, and Mount Melbourne. As

the

result of the application of our calculations to the chart it became

evident

that we had actually crossed the Nordenskjold Ice Barrier of Captain

Scott's

survey, and were now opposite what on his chart was termed Charcot Bay.

This

was good news and cheered us up very much, as it meant that we were

nearly

twenty miles further north than we previously thought we were. The day

was calm

and fine, and the surface of the sea ice was covered with patches of

soft snow

with nearly bare ice between, and the sledging was not quite as heavy

as usual.

In the evening two skua gulls went for our seal meat during the

interval that

we were returning for the second sledge after pulling on the first one.

We had a

magnificent view of the

rocky coast-line, which is here Test impressive. The sea ice stretched

away to

the west of us for several miles up to a low cliff and slope of

piedmont

glacier ice, with occasional black masses of rock showing at its edge.

Several

miles further inland the piedmont glacier ice terminated abruptly

against a

magnificent range of mountains, tabular for the most part but deeply

intersected.

In the wide gaps between this coast range were vast glaciers fairly

heavily

crevassed, descending by steep slopes from an inland plateau to the

sea. We were still

doing our travelling

by night and sleeping during the afternoon. When we arose from our

sleeping-bags at 8 P.M. on the night of November 16, there was a

beautifully

perfect "Noah's Ark" in the sky; the belts of cirrus-stratus

composing the ark stretched from south-south-west to north-north-east,

converging towards the horizon in each of these directions. Fleecy

sheets of

frost smoke arose from over the open water on Ross Sea, and formed

dense

cumulus clouds. This, of course, was a certain indication to us that

open water

was not far distant, and impressed upon us the necessity of making

every

possible speed if we hoped to reach our projected point of departure on

the

coast for the Magnetic Pole before the sea ice entirely broke up. The following

day, November 17,

after a very heavy sledging over loose powdery snow six inches deep, we

reached

a low glacier and ice cliff. We were able to get some really fresh snow

from

this barrier or glacier, the cliffs of which were from thirty to forty

feet

high. It was a great treat to get fresh water at last, as since we had

left the

Nordenskjold Ice Barrier the only snow available for cooking purposes

had been

brackish. November 18 was

bright and sunny,

but the sledging was terribly heavy. The sun had thawed the surface of

the

saline snow and our sledge runners had become saturated with soft

water. We

were so wearied with the great effort necessary to keep the sledges

moving that

at the end of each halt we fell sound asleep for five minutes or so at

a time

across the sledges. On such occasions one of the party would wake the

others

up, and we would continue our journey. We were even more utterly

exhausted than

usual at the end of this day. By this time,

however, we were in

sight of a rocky headland which we took to be Cape Irizar, and we knew

that

this cape was not very far to the south of the Drygalski Glacier.

Indeed,

already a long line was showing on the horizon which could be no other

than the

eastward extension of this famous and, as it afterwards proved,

formidable

glacier. November 19. We

had another heavy

day's sledging, ankle deep in the soft snow. We only did two miles of

relay

work this day, and yet were quite exhausted at the end of it. November 20.

Being short of meat, we

killed a seal calf and cow, and so replenished our larder. At the end

of the

day's sledging I walked over about two miles to a cliff face, about six

miles

south of Cape Irizar. The rocks all along this part of the shore were

formed of

coarse gneissic granite, of which I was able to collect some specimens.

The

cliff was about one hundred feet high where it was formed of the

gneiss, and

above this rose a capping of from seventy to eighty feet in thickness

of

heavily crevassed blue glacier ice. There were here wide tide-cracks

between

the sea ice and the foot of the sea cliff. These were so wide that it

was

difficult to cross them. November 21.

The sledging was

painfully heavy over thawing saline snow surface and sticky sea ice. We

were

only able to do two and two-third miles. November 22. On

rounding the point

of the low ice barrier, thirty to forty feet high, we obtained a good

view of

Cape Irizar, and also of the Drygalski Ice Barrier. November 23. We

found that a mild

blizzard was blowing, but we travelled on through it as we could not

afford to

lose any time. The blizzard died down altogether about 3 A.M., and was

succeeded

by a gentle westerly wind off the plateau. That svening, after our tent

had

been put up and we had finished the day's meal, I walked over a mile to

the

shore. The prevailing rock was still gneissic granite with large

whitish veins

of aplitict granite. A little bright green moss was growing on tiny

patches of

sand and gravel, and in some of the cracks in the granite. The top of

the cliff

was capped by blue glacier ice. With the help of steps cut by my

ice-axe I

climbed some distance up this in order to try and get some fresh ice

for

cooking purposes, but close to the top of the slope I accidentally

slipped and

glissaded most unwillingly some distance down before I was able to

check myself

by means of the chisel edge of the ice-axe. My hands were somewhat cut

and

bruised, but otherwise no damage was done. November 24. A

strong keen wind was

blowing off the plateau from the west-south-west. We were all suffering

from

want of sleep, and although the snow surface was better than it had

been for

some little time we still found the work of sledging very fatiguing. A

three-man sleeping-bag, where you are wedged in more or less tightly

against

your mates, where all snore and shin one another and each feels on

waking that

he is more shinned against than shinning, is not conducive to real

rest; and we

rued the day that we chose the three-man bag in preference to the

one-man bags. On the

following day, November 26,

we saw on looking back that the rocky headland, where I had collected

the

specimens of granite and moss, was not part of the mainland but a small

island. We had some

good sledging here over

pancake ice nearly free from snow and travelled fast. While Mackay

secured some

seal meat Mawson and I ascended the rocky promontory, climbing at first

over

rock, then over glacier ice, to a height of about six hundred feet

above the

sea. The rock was a pretty red granite traversed by large dykes of

black rocks.

From the top of the headland to the north we had a magnificent view

across the

level surface of sea ice far below us. We saw that at a few miles from

the

shore an enormous iceberg, frozen into the floe, lay right across the

path

which we had intended to travel in our northerly course on the morrow.

To the

north-west of us was Geikie Inlet, and beyond that stretching as far as

the eye

could follow was the great Drygalski Glacier. Beyond the Drygalski

Glacier were

a series of rocky hills. One of these was identified as probably being

Mount

Neumayer. Several mountains could be seen further to the north of this,

but the

far distance was obscured from view by cloud and mist so that we were

unable to

make out the outline of Mount Nansen. It was evident that the Drygalski

Glacier

was bounded landwards on the north by a steep cliff of dark, highly

jointed

rock, and we were not a little ooncerned to observe with our

field-glasses that

the surface of the Drygalski Glacier was wholly different to that of

the

Nordenskjold Ice Barrier. It was clear that the surface of the

Drygalski

Glacier was formed of jagged surfaces of ice very heavily crevassed,

and

projecting in the form of immense graes separated from one another by

deep

undulations or chasms; but we could see that, at the extreme eastern

extension,

some thirty miles from where we were standing, the surface appeared

fairly

smooth. It was obvious from what we had seen looking out to sea to the

east of

our camp that there were large bodies of open water trending shorewards

in the

form of long lanes at no great distance. The lanes of water were only

partly

frozen over, and some of these were interposed between us and the

Drygalski

Glacier. Clearly not a moment was to be lost if we were to reach the

glacier

before the sea ice broke up. A single Wong blizzard would now have

converted

the whole of the sea ice between us and the glacier into a mass of

drifting

pack. The following

day, November 27, we

decided to run our sledges to the east of the large berg which we had

observed

on the previous day, and this course apparently would enable us to

avoid a wide

and ugly looking tide-crack extending northwards from the rocky point

at our

previous camp. The temperature was now as high as from plus 26° to plus

28°

Fahr. at mid-day, consequently the saline snow and ice were all day

more or

less sticky and slushy. We camped near the large berg. On the morning

of November 28 we

packed up and started our sledges, and pulled them over a treacherous

slushy

tide-crack, and then headed them round an open lead of water in the sea

ice. At

3 A.M. we had lunch near the east end of the big berg. Near here Mackay

and

Mawson succeeded in catching and killing an Emperor penguin, and took

the

breast and liver. This bird was caught close to a lane of open water in

the sea

ice. We found that

in the direction of

the berg this was thinly frozen ever, and for some time it seemed as

though our

progress further north was completely blocked. Eventually we found a

place

where the ice might just bear our sledges. We strengthened this spot by

laying

down on it slabs of sea ice and shovelfuls of snow, and when the

causeway was

completed not without Mackay breaking through the ice in one place

and very

nearly getting a ducking we rushed our sledges over safely, although

the ice

was so thin that it bent under their weight. We were thankful to get

them both

safely to the other side. We now found

ourselves amongst some

very high sastrugi of hard tough snow. We had to drag the sledges over

a great

number of these, which were nearly at right angles to our course. This

work

proved extremely fatiguing. The sastrugi were from five to six feet in

height.

As we were having dinner at the end of our day's sledging we heard a

loud

report which we considered to be due to the opening of a new crack in

the sea

ice. We thought it was possible that this crack was caused by some

movement of

the great active Drygalski Glacier, now only about four miles ahead of

us to

the north. We got out of

our sleeping-bag soon

after 8 P.M. on the evening of the 28th, and started just before

midnight. The

ice-surface over which we were sledging this day had a curious

appearance

resembling rippling stalagmites, or what may be termed ice marble. This

opacity

appeared to be due to a surface enamel of partly thawed snow. This

surface kept

continually cracking as we passed over it with a noise like that of a

whip

being cracked It was evidently in a state of tension, being contracted

by the

cold which attained its maximum soon after midnight, for, although of

course we

had for many weeks past been having the midnight sun, it was still so

low in

the heavens towards midnight that there was an appreciable difference

in the

temperature between midnight and the afternoon. We were now

getting very short of

biscuits, and as a consequence were seized with food obsessions, being

unable

to talk about anything but cereal foods, chiefly cakes of various kinds

and

fruits. Whenever we halted for a short rest we could discuss nothing

but the

different dishes with which we had been regaled in our former lifetime

at

various famous restaurants and hotels. The plateau

wind blew keenly and

strongly all day on November 29. As we advanced further to the north

the

ice-surface became more and more undulatory, rising against us in great

waves

like waves of the sea. Evidently these waves were due to the forward

movement,