| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XVII

THE FINAL STAGE FEBRUARY 23 TO MARCH 4 Bluff Depot reached: Marshall's Condition worse on February 25: Marshall and Adams remain in Camp while Shackleton and Wild make a Forced March to Hut Point: On board Nimrod: Relief Party start to bring in Marshall and Adams: All Safe on Board Ship March 4, 1908 February

24.

We got up at 5 A.M., and at 7 A.M. had breakfast, consisting of eggs,

dried

milk, porridge, and pemmican, with plenty of biscuits. We marched until

1 P.M.,

had lunch and then marched until 8 rat., covering a distance of fifteen

miles

for the day. The weather was fine. Though we have plenty of weight to

haul now

we do not feel it so much as we did the smaller weights when we were

hungry. We

have good food inside us, and every now and then on the march we eat a

bit of chocolate

or biscuit. Warned by the experience of Scott and Wilson on the

previous

southern journey, I have taken care not to over-eat. Adams has a

wonderful

digestion, and can go on without any difficulty. Wild's dysentery is a

bit

better to-day. He is careful of his feeding and has only taken things

that are

suitable. It is a comfort to be able to pick and choose. I cannot

understand a

letter I received from Murray about Mackintosh getting adrift on the

ice, but

no doubt this will be cleared up on our return. Anyhow, every one seems

to be

all right. There was no news of the Northern Party or of the Western

Party. We

turned in full of food to-night. February

25.

We turned out at 4 A.M. for an early start, as we are in danger of

being left

if we do not push ahead rapidly and reach the ship. On going into the

tent for

breakfast I found Marshall suffering from paralysis of the stomach and

renewed

dysentery, and while we were eating a blizzard came up. We secured

everything

as the Bluff showed masses of ragged cloud, and I was of opinion that

it was

going to blow hard. I did not think Marshall fit to travel through the

blizzard. During the afternoon, as we were lying in the bags, the

weather

cleared somewhat, though it still blew hard. If Marshall is not better

to-night,

I must leave him with Adams and push on, for time is going on, and the

ship may

leave on March 1, according to orders, if the Sound is not clear of

ice. I went

over through the blizzard to Marshall's tent. He is in a bad way still,

but

thinks that he could travel to-morrow. February 27

(1 A.M.). The blizzard was over at midnight, and we got up at 1 A.M.,

had

breakfast at 2, and made a start at 4. At 9.30 A.M. we had lunch, at 3

P.M.

tea, at 7 P.M. hoosh, and then marched till 11 P.M. Had another hoosh,

and

turned in at 1 A.M. We did twenty-four miles. Marshall suffered

greatly, but

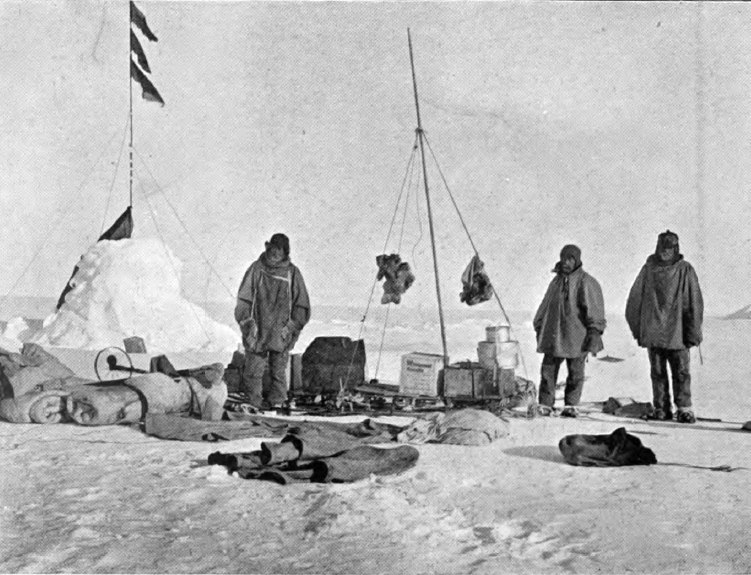

stuck to the march. He never complains.  RETURN JOURNEY OF THE SOUTHERN PARTY: AT THE BLUFF DEPOT March 5.

Although we did not turn in until 1 A.M. on Feb. 27th, we were up again

at 4 A.M.

and after a good hoosh, we got under way at 6 A.M. and marched until 1

P.M.

Marshall was unable to haul, his dysentery increasing, and he got worse

in the

afternoon, after lunch. At 4 P.M. I decided to pitch camp, leave

Marshall under

Adams' charge, and push ahead with Wild, taking one day's provisions

and

leaving the balance for the two men at the camp. I hoped to pick up a

relief

party at the ship. We dumped everything off the sledge except a

prismatic

compass, our sleeping-bags and food for one day, and at 4.30 P.M. Wild

and I

started, and marched till 9 P.M. Then we had a hoosh, and marched until

2 A.M.

of the 28th, over a very hard surface. We stopped for one hour and a

half off

the north-east end of White Island, getting no sleep, and marched till

11 A.M.,

by which time our food was finished. We kept flashing the heliograph in

the

hope of attracting attention from Observation Hill, where I thought

that a

party would be on the look-out, but there was no return flash. The only

thing

to do was to push ahead, although we were by this time very tired. At

2.30 P.M.

we sighted open water ahead, the ice having evidently broken out four

miles

south of Cape Armitage, and an hour and a half later a blizzard wind

started to

blow, and the weather got very thick. We thought once that we saw a

party

coming over to meet us, and our sledge seemed to grow lighter for a few

minutes, but the "party" turned out to be a group of penguins at the

ice-edge. The weather was so thick that we could not see any distance

ahead,

and we arrived at the ice edge suddenly. The ice was swaying up and

down, and

there was grave risk of our being carried out. I decided to abandon the

sledge,

as I felt sure that we would get assistance at once when we reached the

hut,

and time was becoming important. It was necessary that we should get

food and

shelter speedily. Wild's feet were giving him a great deal of trouble.

In the

thick weather we could not risk making Pram Point, and I decided to

follow

another route seven miles round by the other side of Castle Rock. We

clambered

over crevasses and snow slopes, and after what seemed an almost

interminable

struggle reached Castle Rock, from whence I could see that there was

open water

all round the north. It was indeed a different home-coining from what

we had

expected. Out on the Barrier and up on the plateau our thoughts had

often

turned to the day when we would get back to the comfort and plenty of

the

winter quarters, but we had never imagined fighting our way to the

back-door, so

to speak, in such a cheerless fashion. We reached the top of Ski Slope

at 7.45 P.M.,

and from there we could see the hut and the bay. There was no sign of

the ship,

and no smoke or other evidence of life at the hut. We hurried on to the

hut,

our minds busy with gloomy possibilities, and found not a man there.

There was

a letter stating that the Northern Party had reached the Magnetic Pole,

and

that all the parties had been picked up except ours. The letter added

that the

ship would be sheltering under Glacier Tongue until February 26. It was

now

February 28, and it was with very keen anxiety in our minds that we

proceeded

to search for food. If the ship was gone, our plight, and that of the

two men

left out on the Barrier, was a very serious one. We improvised a

cooking vessel,

found oil and a Primus lamp, and had a good feed of biscuit, onions,

and plum

pudding, which were amongst the stores left at the hut. We were utterly

weary

but we had no sleeping-gear, our bags having been left with the sledge,

and the

temperature was very low. We found a piece of roofing felt, which we

wrapped

round us, and then we sat up all night, the darkness being relieved

only when

we occasionally lighted the lamp in order to secure a little warmth. We

tried

to burn the magnetic hut in the hope of attracting attention from the

ship, but

we were not able to get it alight. We tried, too, to tie the Union Jack

to

Vince's cross, on the hill, but we were so played out that our cold

fingers

could not manage the knots. It was a bad night for us, and we were glad

indeed

when the light came again. Then we managed to get a little warmer, and

at 9 A.M.

we got the magnetic hut alight, and put up the flag. All our fears

vanished when in the

distance we saw the ship, miraged up. We signalled with the heliograph,

and at

11 A.M. on March 1 we were on board the Nimrod

and once more safe amongst friends. I will not attempt to describe our

feelings. Every one was glad to see us, and keen to know what we had

done. They

had given us up for lost, and a search-party had been going to start

that day

in the hope of finding some trace of us. I found that every member of

the

expedition was well, that the plans had worked out satisfactorily, and

that the

work laid down had been carried out. The ship had brought nothing but

good news

from the outside world. It seemed as though a great load had been

lifted from

my shoulders. The first thing

was to bring in

Adams and Marshall, and I ordered out a relief party at once. I had a

good feed

of bacon and fried bread, and started at 2.30 P.M. from the Barrier

edge with

Mackay, Mawson, and McGillan, leaving Wild on the Nimrod.

We marched until 10 P.M., had dinner and turned in for a

short sleep. We were up again at 2 A.M. the next morning (March 2), .4

and

travelled until 1 P.M., when we reached the camp where I f had left the

two

men. Marshall was better, the rest having done him a lot of good, and

he was

able to march and pull. After lunch we started back again, and marched

until 8

P.M. in fine weather. We were under way again at 4 A.M. the next

morning, had

lunch at noon, and reached the ice-edge at 3 P.M. There was no sign of

the

ship, and the sea was freezing over. We waited until 5 P.M., and then

found

that it was possible to strike land at Pram Point. The weather was

coming on

bad, clouding up from the south-east, and Marshall was suffering from

renewed

dysentery, the result of the heavy marching. We therefore abandoned one

tent

and one sledge at the ice-edge, taking on only the sleeping-bags and

the

specimens. We climbed up by Crater Hill, leaving everything but the

sleeping-bags, for the weather was getting worse, and at 9.35 P.M.

commenced to

slide down towards Hut Point. We reached the winter quarters at 9.50,

and

Marshall was put to bed. Mackay and I lighted a carbide flare on the

hill by

Vince's cross, and after dinner all hands turned in except Mackay and

myself. A

short time after Mackay saw the ship appear. It was now blowing a hard

blizzard, but Mackintosh had seen our flare from a distance of nine

miles. Adams

and I went on board the Nimrod, and

Adams, after surviving all the dangers of the interior of the Antarctic

continent, was nearly lost within sight of safety. He slipped at the

ice-edge,

owing to the fact that he was wearing new finnesko, and he only just

saved

himself from going over. He managed to hang on until he was rescued by

a party

from the ship. A boat went

back for Marshall and

the others, and we were all safe on board at 1 A.M. on March 4.  THE SOUTHERN PARTY ON BOARD THE "NIMROD." LEFT TO RIGHT: WILD, SHACKLETON, MARSHALL, ADAMS |