| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

IV GENERAL METHODS OF PLAY AND TERMINOLOGY OF THE GAME There is, however, an old rule of

etiquette which is

not consistent with this theory of the opening; it used to be regarded

as

exceedingly impolite and insulting to play the first stone on the

handicap

point in the center of the board, called "Ten gen." It has been

explained to me that the reason for this rule is that such a move was

supposed

to assure the victory to the first player, and it is related that when

on one

occasion Murase Shuho had defeated a rival many times in succession,

the

latter, becoming desperate, apologized for his rudeness and placed his

stone on

this spot, and Murase, nevertheless, succeeded in winning the game,

which was

regarded as evidence of his great skill. It has, however, been shown by

Honinbo

Dosaku that this move gives the first player no decisive advantage, and

I have

been also told by some Japanese that the reason that this move is

regarded as

impolite is because it is a wasted move, and implies a disrespect for

the

adversary's skill, and from what experience I have had in the game I

think the

latter explanation is more plausible. At all events, such a move is

most

unusual and can only be utilized by a player of the highest skill. When good players commence the game, from

the first

they have in mind the entire board, and they generally play a stone in

each of

the four corners and one or two around the edges of the board,

sketching out,

as it were, the territory which they ultimately hope to obtain. They do

not at

once attack each other's stones, and it is not until the game is well

advanced

that anything like a hand to hand conflict occurs. Beginners are likely

to

engage at once in a close conflict. Their minds seem to be occupied

with an

intense desire to surround and capture the first stones the adversary

places on

the board, and often their opposing groups of stones, starting in one

corner,

will spread out in a struggling mass from that point all over the

board. There

is no surer indication of the play of a novice than this. It is just as

if a

battle were to commence without the guidance of a commanding officer,

by

indiscriminate fisticuffs among the common soldiers. Of the other

extreme, or

"Ji dori Go," we have already spoken. Another way in which the play

of experts may be recognized is that all the stones of a good player

are likely

to be connected in one or at most two groups, while poorer players find

their

stones divided up into small groups each of which has to struggle to

form the

necessary two "Me" in order to insure survival. Assuming that we have advanced far enough

to avoid

premature encounters or "Ji dori Go," and are placing our stones in

advantageous positions, decently and in order, the question arises, how

many

spaces can be safely skipped from stone to stone in advancing our

frontiers;

that is to say, how far can stones be separated and yet be potentially

connected, and therefore safe against attack? The answer is, that two

spaces

can safely be left if there are no adversary's stones in the immediate

vicinity. To demonstrate this, let us suppose that Black has stones at

R 13 and

R 16, and White tries to cut them off from each other. White's best

line of

attack would be as follows:

and

Black has made good his

connection, or Black at his fourth move could play at Q 14, then

There are other continuations, but they

are still

worse for White. If, however, the adversary's stones are already posted

on the

line of advance sometimes it is only safe to skip one point, and of

course in

close positions the stones must be played so that they are actually

connected.

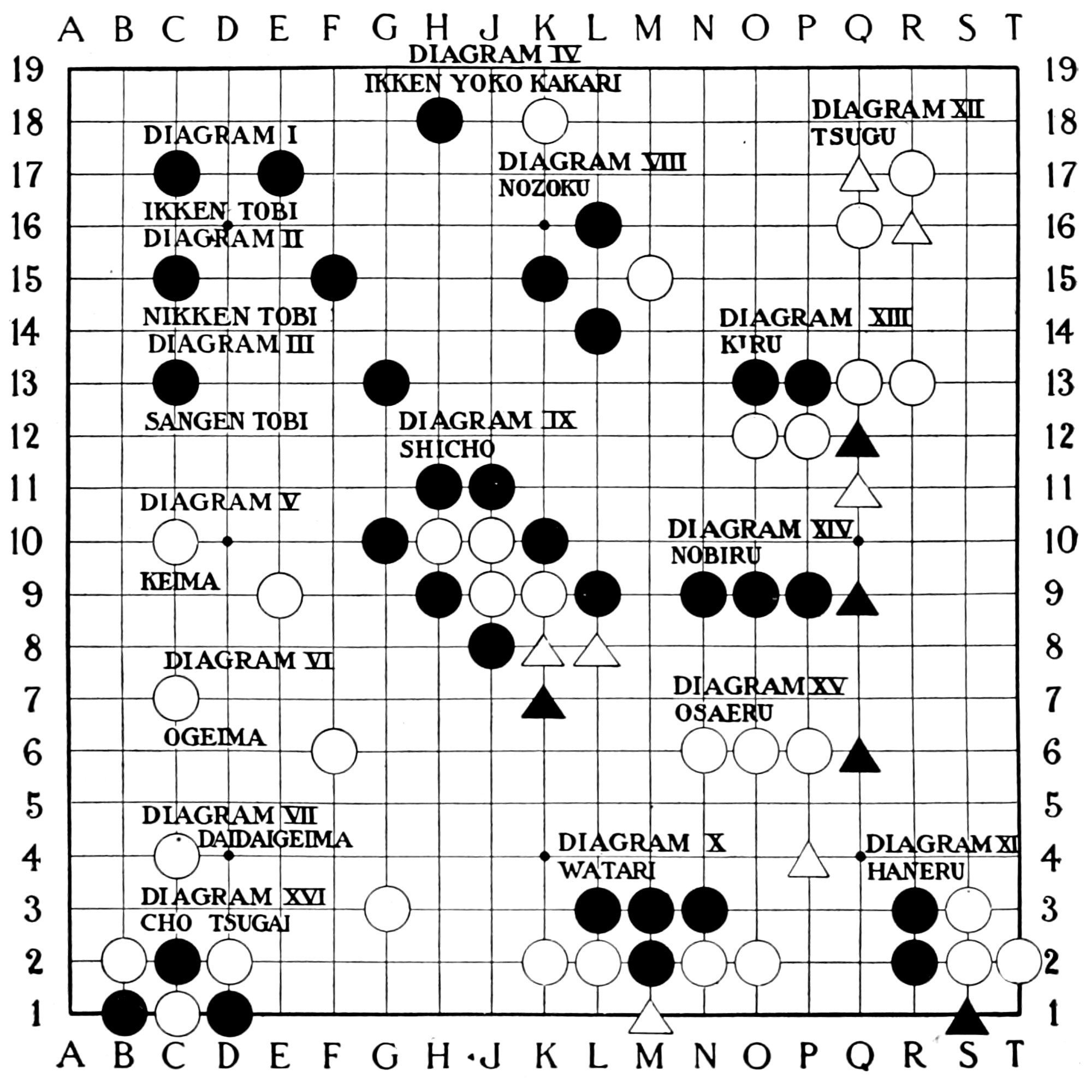

The Japanese call this skipping of "Me" by the terms "Ikken

tobi," "Nikken tobi," "Sangen tobi," etc., which

literally means "to fly one, two, or three spaces." Although this is

plain enough, these relations are nevertheless shown on Plate 13,

Diagrams i, ii,

and iii. When stones of

opposite

colors on the same line are separated by vacant space in a similar way

(Diagram iv), then the

terms "Ikken

kakari," "Nikken kakari," etc., are used. "Kakari"

really means "to hang" or "to be related," but as used in

this sense it might be translated "to attack." Sometimes the stones are placed in

relation to each

other like the Knight's move in Chess. The Knight in Japanese is called

"Keima," or "the honorable horse," and if the stones are of

the same color the relation is called "Keima" or "Kogeima,"

"Ko" being the diminutive. If the stones are of opposite colors, then

the phrase "Keima" or "Kogeima kakari" is used as in the

previous case. The Japanese also designate a relation similar to the

Knight's

move, but farther apart, by special words; thus, if the stones are one

space

farther apart, it is called "Ogeima," or "the Great Knight's

move," and if the stone is advanced one step still farther, it is

called

"Daidaigeima," or "the Great Great Knight's move." On Plate

13, Diagrams v, vi, and vii,

are shown "Kogeima," "Ogeima," and "Daidaigeima." The next question that will trouble the

beginner is

where to place his stones when his adversary is advancing into his

territory,

and beginners are likely to play their stones directly in contact with

the

advancing forces. This merely results in their being engulfed by the

attacking

line, and the stones and territory are both lost. If you wish to stop

your

adversary's advance, play your stones a space or two apart from his, so

that

you have a chance to strengthen your line before his attack is upon

you. The next thing we will speak of is what

the Japanese

call the "Sente." This word means literally "the leading

hand," but is best translated by our words "having the

offensive." It corresponds quite closely to the word "attack,"

as it is used in Chess, but in describing a game of Go it is better to

reserve

the word "attack" for a stronger demonstration than is indicated by

the word "Sente." The "Sente" merely means that the player

having it can compel his adversary to answer his moves or else sustain

worse

damage, and sometimes one player will have the "Sente" in one portion

of the board, and his adversary may disregard the attack and by playing

in some

other quarter take the "Sente" there. Sometimes the defending player

by his ingenious moves may turn the tables on his adversary and wrest

the

"Sente" from him. At all events, holding the "Sente" is an

advantage, and the annotations on illustrative games abound with

references to

it, and conservative authors on the game advise abandoning a stone or

two for

the purpose of taking the "Sente."  Plate 13 Sometimes a player has three stones

surrounding a

vacant space, as shown in Plate 13, Diagram viii,

and the question arises how to attack this group. This is done by

playing on

the fourth intersection. The Japanese call this "Nozoku," or

"peeping into," and when a stone is played in this way it generally

forces the adversary to fill up that "Me." It may be mentioned here

also that when your adversary is trying to form "Me" in a disputed

territory, the way to circumvent him is to play your stones on one of

the four

points he will obviously need to complete his "Me," and sometimes

this is done before he has three of the necessary stones on the board.

The term

"Nozoku" is also applied to any stone which is played as a

preliminary move in cutting the connection between two of the

adversary's

stones or groups of stones. Sometimes a situation occurs as shown in

Plate 13,

Diagram ix. Here it is

supposed to

be White's move, and he must, of course, play at K 8, whereupon

Black

would play at K 7 ("Osaeru"), and White would have to play at

L 8 ("Nobiru"), and so on until, if these moves were persisted

in, the formation would stretch in a zigzag line to the edge of the

board. This

situation is called "Shicho," which really means a "running

attack." It results in the capture of the white stones when the edge of

the board is reached, unless they happen to find a comrade posted on

the line

of retreat, for instance, at P 4, in which case they can be saved.

Of

course, between good players "Shicho" is never played out to the end,

for they can at once see whether or not the stones will live, and often

a stone

placed seemingly at random in a distant part of the board is played

partly with

the object of supporting a retreating line should "Shicho" occur. Plate 13, Diagram x,

shows a situation that often arises, in which the White player, by

putting his

stone at M 1 on the edge of the board, can join his two groups of

stones.

This is so because if Black plays at L 1 or N 1, white can

immediately kill the stone. This joining on the edge of the board is

called by

the special term "Watari," which means "to cross over."

Sometimes we find the word "Watari" used when the connection between

two groups is made in a similar way, although not at the extreme edge

of the

board. A much more frequent situation is shown at

Plate 13,

Diagram xi. It is not

worthy of

special notice except because a special word is applied to it. If Black

plays

at S 1, it is called "Haneru," which really means the flourish

which is made in finishing an ideograph. We will now take up a few of the other

words that are

used by the Japanese as they play the game. By far the most frequent of

these

are "Tsugu," "Kiru," "Nobiru," and

"Osaeru." "Tsugu" means "to connect," and when

two stones are adjacent but on the diagonal, as shown in Plate 13,

Diagram xii, it is

necessary to connect them if

an attack is threatened. This may be done by playing on either side;

that is to

say, at Q 17 or R 16. If, on the other hand, Black should

play on

both these points, the white stones would be forever separated, and

this

cutting off is called "Kiru," although, as a rule, when such a

situation is worthy of comment, one of the intersections has already

been

filled by the attacking player. Plate 13, Diagram xiii, illustrates "Kiru,"

where, if a black stone

is played at Q 12, the white stones are separated. "Kiru" means

"to cut," and is recognizable as one of the component parts of that

much abused and mispronounced word "Harakiri." "Nobiru"

means "to extend," and when there is a line of stones it means the

adding of another one at the end, not skipping a space as in the case

of

"Ikken tobi," but extending with the stones absolutely connected. In

Plate 13, Diagram xiv,

if Black

plays at Q 9 it would be called "Nobiru." "Osaeru"

means "to press down," and this is what we do when we desire to

prevent our adversary from extending his line, as seen in the preceding

diagram. It is done by playing directly at the end of the adversary's

line, as

shown in Diagram xv,

where Black

is supposed to play at Q 6. Here White must play on one side of

the black

stone, but it must be pointed out that unless there is support in the

neighborhood for the stone used in "Osaeru," the stone thus played

runs the risk of capture. In Diagram ix,

explaining "Shicho," we also had an illustration of

"Nobiru" and "Osaeru." If a stone is played on the intersection

diagonally

adjacent to another stone, it is called "Kosumu," but this word is

not nearly so much used as the other four. Sometimes, also, when it is

necessary to connect two groups of stones instead of placing the stone

so as

actually to connect them, as in the case of "Tsugu," the stone is

played so as to effectively guard the point of connection and thus

prevent the

adversary's stone from separating the two groups. This play is called

"Kake tsugu," or "a hanging connection"; e.g., in

Diagram xiii, if a

white stone

were played at Q 11 it would be an instance of "Kake tsugu" and

would have prevented the black stone from cutting off the White

connection at

Q 12, for, if the black stone were played there after a white

stone had

been placed at Q 11, White could capture it on the next move. Passing from these words which describe

the commonest

moves in the game, we will mention the expression "Te

okure"—literally "a slow hand" or "a slow move," which

means an unnecessary or wasted move. Many of the moves of a beginner

are of

this character, especially when he has a territory pretty well fenced

in and

cannot make up his mind whether or not it is necessary to strengthen

the group

before proceeding to another field of battle. In annotating the best

games, also,

it is used to mean a move that is not the best possible move, and we

frequently

hear it used by Japanese in criticising the play. "Semeai" is another word with which we

must

be familiar. It means "mutually attacking," from "Semeru,"

"to attack," and "Au," "to encounter," that is to

say, if the White player attacks a group of black stones, the Black

player

answers by endeavoring to surround the surrounding stones, and so on.

In our

Illustrative Game, Number i,

the

play in the upper right-hand corner of the board is an example of

"Semeai." It is in positions of this kind that the condition of

affairs called "Seki" often comes about. Plate 13, Diagram xvi,

shows a position which is illustrated only because a special name is

applied to

it. The Japanese call such a relation of stones "Cho tsugai,"

literally, "the hinge of a door." The last expression which we will give is

"Naka

oshi gatchi," which is the term applied to a victory by a large margin

in

the early part of the game. These Japanese words mean "to conquer by

pushing the center." Beginners are generally desirous of achieving a

victory in this way, and are not content to allow their adversary any

portion

of the board. It is one of the first things to be remembered, that, no

matter

how skilful a player may be, his adversary will always be able to

acquire some

territory, and one of the maxims of the game is not to attempt to

achieve too

great a victory. Before proceeding with the technical

chapters on the

Illustrative Games, Openings, etc., it may be well to say a word in

regard to

the method adopted for keeping a record of the game. The Japanese do

this by

simply showing a picture of the finished game, on which each stone is

numbered

as it was played. If a stone is taken and another stone is put in its

place, an

annotation is made over the diagram of the board with a reference to

that

intersection, stating that such a stone has been taken in "Ko." Such

a method with the necessary marginal annotation is good enough, but it

is very

hard to follow, as there is no means of telling where any stone is

without

searching all over the board for it; and while the Japanese are very

clever at

this, Occidental students of the game do not find it so easy.

Therefore, I have

adopted the method suggested by Korschelt, which in turn is founded on

the

custom of Chess annotation in use all over the world. The lines at the

bottom

of the board are lettered from A to T, the letter I being omitted, and

at the

sides of the board they are numbered up from 1 to 19. Thus it is always

easy to

locate any given stone. In the last few years the Japanese have

commenced to

adopt an analogous method of notation. |