| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

III

RULES OF PLAY The players play alternately, and the weaker

player has

the black stones and plays first, unless a handicap has been given, in

which

case the player using the white stones has the first move. (In the

olden times

this was just reversed.) They place the stones on the vacant points of

intersection on the board, or “Me,” and they may place them wherever

they

please, with the single exception of the case called “Ko,” which will

be

hereafter explained. When the stones are once played they are never

moved

again. The object of the game of Go is to secure

territory.

Just as the object of the game of Chess is not to capture pieces, but

to

checkmate the adverse King, so in Go the ultimate object is not to

capture the

adversary’s stones, but to so arrange matters that at the end of the

game a

player’s stones will surround as much vacant space as possible. At the

end of

the game, however, before the amount of vacant space is calculated, the

stones

that have been taken are used to fill up the vacant spaces claimed by

the

adversary; that is to say, the captured black stones are used to fill

up the

spaces surrounded by the player having the white pieces, and vice

versa, and

the player who has the greatest amount of territory after the captured

stones

are used in this way, is the winner of the game. However, if the

players,

fearing each other, merely fence in parts of the board without regard

to each

other’s play, a most uninteresting game results, and the Japanese call

this by

the contemptuous epithet “Ji dori go,” or “ground taking Go.” I have

noticed

that beginners in this country sometimes start to play in this way, and

it is

one of the many ways by which the play of a mere novice may be

recognized. The

best games arise when the players in their efforts to secure territory

attack

each other’s stones or groups of stones, and we therefore must know how

a stone

can be taken. A stone is taken when it is surrounded on

four

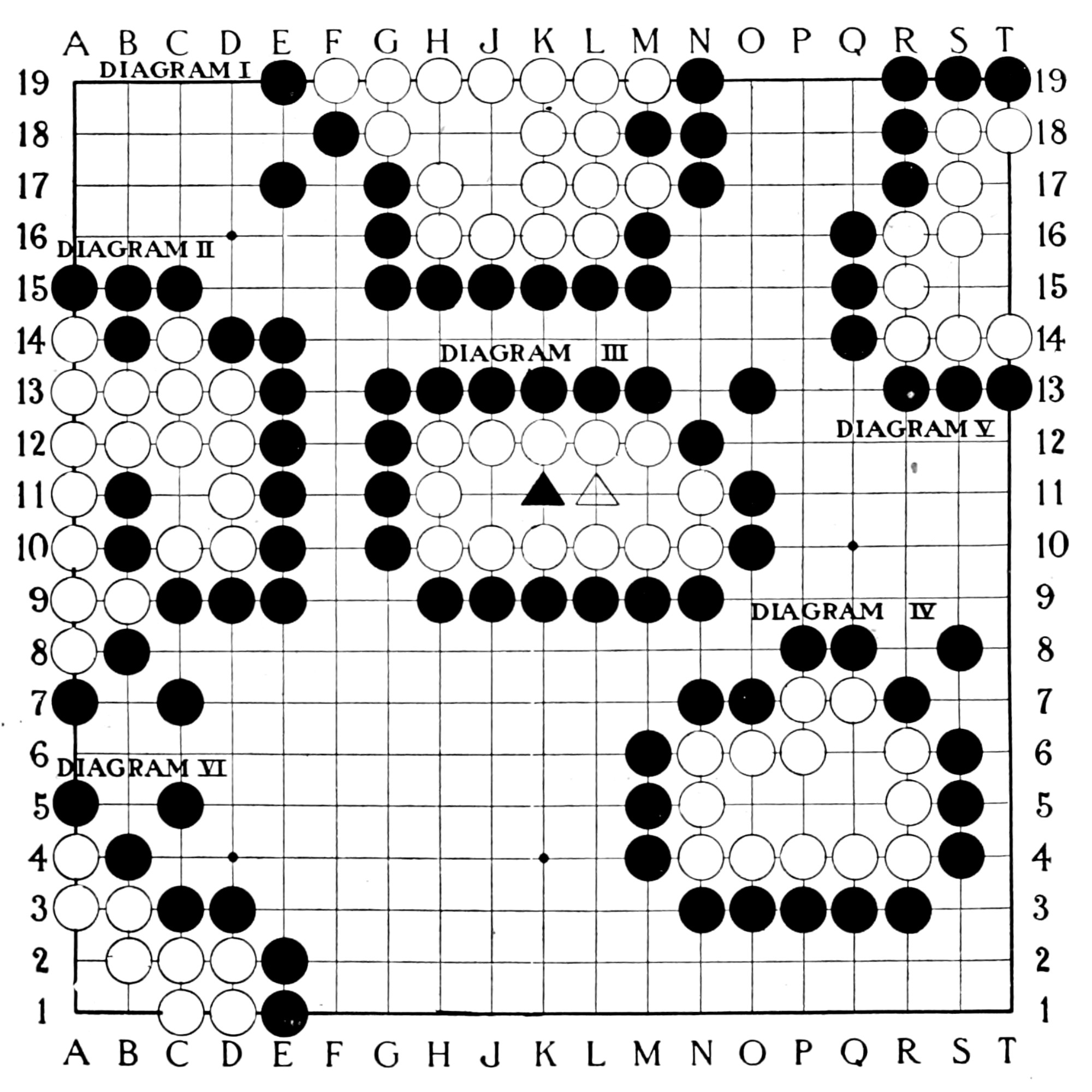

opposite sides as shown in Plate 2, Diagram i.

When it is taken it is removed from the board. It is not necessary that

a stone

should also be surrounded diagonally, which would make eight stones

necessary

in order to take one; neither do four stones placed on the adjacent

diagonal

intersections cause a stone to be taken: they do not directly attack

the stone

in the center at all. Plate 2, Diagram iv,

shows this situation. A stone which is placed on the edge of the

board may

be surrounded and captured by three stones, as shown in Plate 2,

Diagram ii, and if a

stone is placed in the

extreme corner of the board, it may be surrounded and taken by two

stones, as

shown in Plate 2, Diagram iii.

In actual practice it seldom or never

happens that a

stone or group of stones is surrounded by the minimum number requisite

under

the rule, for in that case the player whose stones were threatened

could

generally manage to break through his adversary’s line. It is almost

always

necessary to add helping stones to those that are strictly necessary in

completing the capture. Plate 2, Diagram v,

shows four stones which are surrounded with the minimum number of

stones. Plate

2, Diagram vi, shows

the same

group with a couple of helping stones added, which would probably be

found

necessary in actual play. It follows from this rule that stones

which are on

the same line parallel with the edges of the board are connected, and

support

each other, Plate 2, Diagram vii,

while stones which are on the same diagonal line are not

connected, and

do not support each other, Plate 2, Diagram viii.

In order to surround stones which are on the same line, and therefore

connected, it is necessary to surround them all in order to take them,

while

stones which are arranged on a diagonal line, and therefore

unconnected, may be

taken one at a time. On Plate 2, Diagram iii,

if there were a stone placed at S 18, it would not be connected

with the

stone in the corner, and would not help it in any way. On the other

hand, as

has been said, it is not necessary to place a white stone on that point

in

order to complete the capture of the stone in the corner. In order to capture a group or chain of

stones

containing vacant space, it must be completely surrounded inside and

out; for

instance, the black group shown on Plate 2, Diagram ix, while it has no hope of

life if it is White’s play is

nevertheless not completely surrounded. In order to surround it, it is

necessary to play on the three vacant intersections at M 11,

N 11,

and O 11. The same group of stones is shown in Diagram x completely surrounded. (It

may be said

in passing that White must play at N 11 first or the black stones

can

defend themselves; we shall understand this better in a moment.) In practice it often happens that a stone

or group of

stones is regarded as dead before it is completely surrounded, because

when the

situation is observed to be hopeless the losing player abandons it, and

addresses his energies to some other part of the board. It is

advantageous for

the losing player to abandon such a group as soon as possible, for, if

he

continues to add to the group, he loses not only the territory but the

added

stones also. If the circumstances are such that his opponent has to

reply to

his moves in the hopeless territory, the loss is not so great, as the

opponent

is meanwhile filling up spaces which would otherwise be vacant, and

against an

inferior player there is a chance of the adversary making a slip and

allowing

the threatened stones to save themselves. If, however, the situation is

so

clearly hopeless that the adversary is not replying move for move, then

every

stone added to such a group means a loss of two points.  Plate 2 As a corollary to the rule for surrounding

and taking

stones, it follows that a group of stones containing two disconnected

vacant

intersections or “Me” cannot be taken. This is not a separate rule. It

follows

necessarily from the method by which stones are taken. Nevertheless in

practice

it is the most important principle in the game. In order to understand the rule or

principle of the

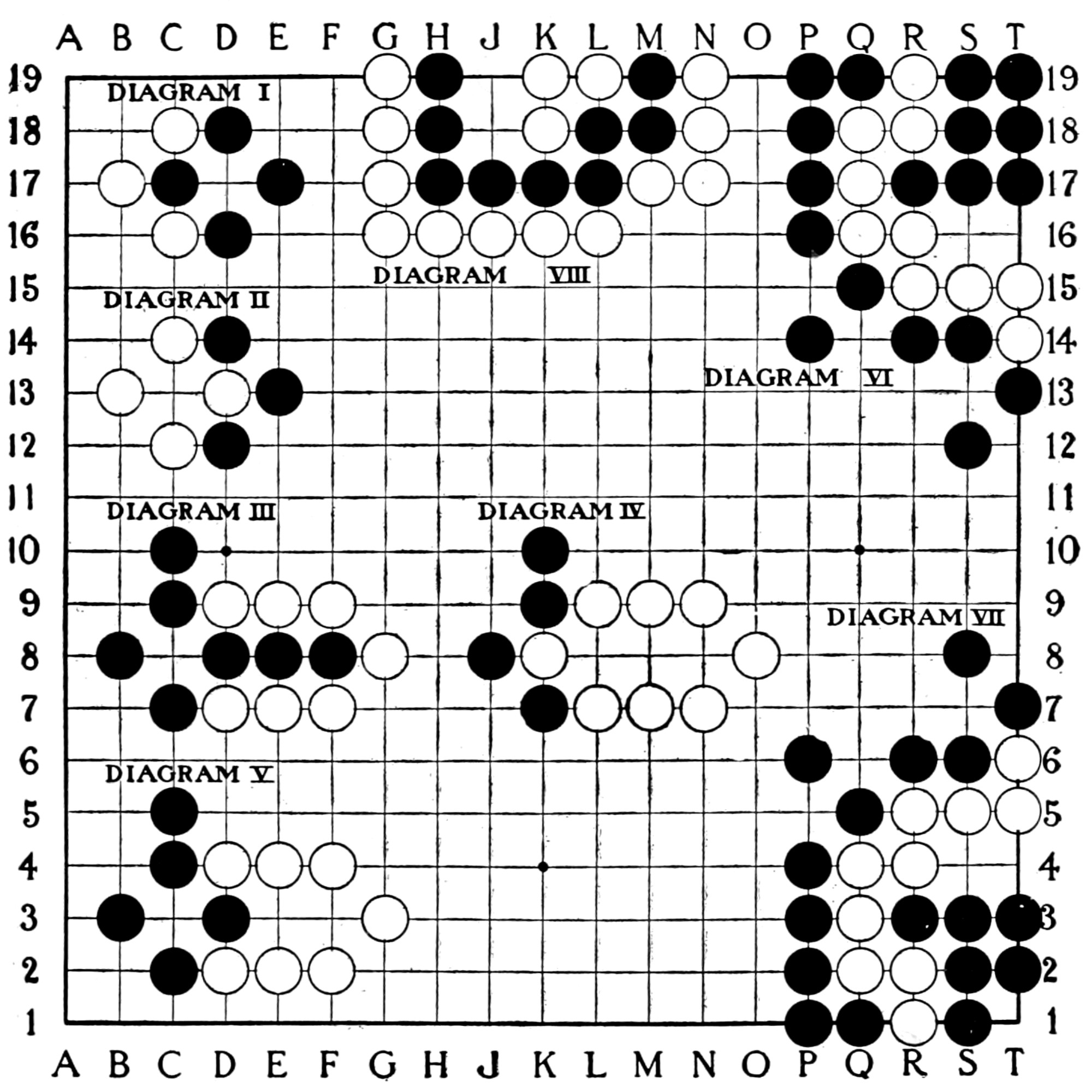

two “Me,” we must first look at the situation shown in Plate 3, Diagram

i. There, if a

black stone is played at

F 15, although it is played on an intersection entirely surrounded

by

white stones, it nevertheless lives because the moment it is played it

has the

effect of killing the entire white group; that is to say, a stone may

be played

on an intersection where it is completely surrounded if as it is played

it has

the effect of completely surrounding the adversary’s stones already on

the

board. If, on the other hand, we have a situation as shown in Plate 3,

Diagram ii, a black

stone may indeed be played

on one of the vacant intersections, but when it is so played the white

group is

not completely surrounded, because there still remains one space yet to

be

filled, and the black stone itself is dead as soon as it touches the

board, and

hence it would be impossible to surround this group of white stones

unless two

stones were played at once. The white stones, therefore, can never be

surrounded, and form an impregnable position. This is the principle of the two "Me," and

when a player's group of stones is hard pressed, and his adversary is

trying to

surround them, if he can so place the stones that two disconnected

complete

"Me" are left, they are safe forever. It makes no difference whether

the vacant "Me" are on the edges or in the corners of the board, or

how far from each other they may be. Plate 3, Diagram vi,

shows a group of stones containing two vacant "Me" on the edge of the

board. This group is perfectly safe against attack. A beginner might

ask why

the white group shown on Plate 3, Diagram v,

is not safe. The difficulty with that group is, that when Black has

played at

S 9, there are no "Me" in it at all as the word is used in this

connection, not even a "Kageme" as shown in Plate 3, Diagram iii, because a "Me," in order

to be available for the purpose of defense, must be a vacant

intersection that

is surrounded on four sides, just as a captured stone must be

surrounded and

therefore on the sides of the board it can be made by three stones, and

in the

corner of the board by two stones, but it is absolutely necessary, in

addition

to the minimum number of surrounding stones, to have helping stones to

guard

the surrounding stones against attack. This brings us to what the

Japanese call

"Kageme." In actual play there are many groups of

stones that

at first glance seem to have two vacant "Me" in them, but which on

analysis, will be found vulnerable to attack. A "Me" that looks

somewhat as if it were complete, but is, nevertheless, destructible is

called

"Kageme." "Kage" means "chipped" or

"incomplete." Plate 3, Diagram iii,

is an illustration of this. A beginner might think that the white group

was

safe, but Black can kill the upper six white stones by playing at

E 3, and

then on the next move can kill the remainder by playing at G 2.

Therefore,

E 3 is not a perfect "Me," but is "Kageme." G 2

is a perfect "Me," but one is not enough to save the group. In this

group if the stone at F 4 or D 2 were white, there would be

two

perfect "Me," and the group would be safe. In a close game beginners

often find it difficult to distinguish between a perfect "Me" and

"Kageme." Groups of stones which contain vacant

spaces, can be

lost or saved according as two disconnected "Me" can or cannot be

formed in those spaces, and the most interesting play in the game

occurs along

the sides and especially in the corners of the board in attempting to

form or

attempting to prevent the formation of these "Me." The attacking

player often plays into the vacant space and sacrifices several stones

with the

ultimate object of reducing the space to one "Me"; and, on the other

hand, the defending player by selecting a fortunate intersection may

make it impossible

for the stones to be killed. There is opportunity for marvelous

ingenuity in

the attack and defense of these positions. A simple example of defense

is shown

in Plate 3, Diagram iv,

where, if

it is White's turn, and he plays in the corner of the board at

T 19, he

can save his stones. If, on the other hand, he plays anywhere else, the

two

"Me" can never be formed. The beginner would do well to work out this

situation for himself. The series of diagrams commencing at Plate

3, Diagram v, show the

theoretical method of

reducing vacant spaces by the sacrifice of stones. This series is taken

from

Korschelt, and the position as it arose in actual play is shown on

Plate 10,

depicting a complete game. In Plate 3, Diagram v,

the white group is shown externally surrounded, and the black stone has

just

been played at S 9, rendering the group hopeless. The same group

is shown

on the opposite side of the board at Plate 4, Diagram i, but Black has added three

more stones and could kill the

white group on the next move. Therefore, White plays at A 12, and

the

situation shown in Plate 4, Diagram ii,

arises, where the same

group is shown on the lower edge of the board. Now, if it were White's

move, he

could save his group by playing at J 2, and the situation which

would then

arise is shown on Plate 4, Diagram iii,

where White has three perfect "Me," one more than enough. However, it

is not White's move, and Black plays on the coveted intersection, and

then adds

two more stones until the situation shown in Plate 4, Diagram iv, arises. Then White must

again play

at S 8 in order to save his stones from immediate capture, and the

situation shown at Plate 5, Diagram i,

comes about. Black again plays at J 18, adds one more stone, and

we have

the situation shown in Plate 5, Diagram ii,

where it is obvious that White must play at C 11 in order to save

his

group from immediate capture, thus leaving only two vacant spaces. It

is

unnecessary to continue the analysis further, but at the risk of

explaining

what is apparent, it might be pointed out that Black would play on one

of these

vacant spaces, and if White killed the stone (which it would not pay

White to

do) Black would play again on the space thus made vacant, and

completely

surround and kill the entire white group.  Plate 3

Plate 4 As we have previously seen, in actual play

this white

group would be regarded as “dead” as distinguished from “taken,” and

this

series of moves would not be played out. White obviously would not play

in the

space, and he could not demand that Black play therein in order to

complete the

actual surrounding of the stones, and the only purpose of giving this

series of

diagrams is to show theoretically how the white stones can be killed.

However,

the killing of these stones would be necessary if the surrounding black

line

were in turn attacked (“Semeai”), in which case it might be a race to

see

whether the internal white stones could be completely surrounded and

killed

before the external white group could get in complete contact with the

black

line.  Plate 5 Stones which are sacrificed in order to

kill a larger

group are called “Sute ishi” by the Japanese, from “Suteru,” meaning

“to cast

or throw away,” and “Ishi,” a “stone.” It may be noted that if a group contains

four

connected vacant intersections in a line it is safe, because if the

adversary

attempts to reduce it, two disconnected “Me” can be formed in the space

by

simply playing a stone adjacent to the adversary’s stone, as shown in

Plate 5,

Diagram iii, where if

Black plays

for instance at K 11, White replies at L 11, and secures two

“Me.”

Even if these four connected vacant intersections are not in a straight

line,

they are nevertheless sufficient for the purpose, provided the fourth

"Me" is connected at the end of the three, and the Japanese express

this by their saying "Magari shimoku wa me," or four "Me"

turning a corner. Neither does it make any difference whether the four

connected "Me" are in the center of the board or along the edge. On

Plate 5, Diagrams iv

and v, are examples of

"Magari shimoku

wa me," and they both are safe. It is interesting, however, to compare

these situations with that shown at Plate 4, Diagram ii, where the fourth

intersection is not connected at the

end of the line, and which group Black can kill if it is his move, as

we

already have seen. If, however, such a group contains only

three

connected vacant intersections, and it is the adversary's move, it can

be

killed, because the adversary by playing on the middle intersection can

prevent

the formation of two disconnected "Me." We saw a group of this kind

on Plate 2, Diagram ix,

which can

be killed by playing at N 11. Obviously, if it is Black's move in

this

case, the group can be saved by playing at N 11; obviously, also,

if

White, being a mere novice, plays elsewhere than at N 11, Black

saves the

stones by playing there and killing the white stone. Plate 5, Diagram vi, shows another group

containing only

three vacant intersections. These can be killed if it is Black's move

by

playing at A 1. On the other hand, if it is White's move, he can

save them

by playing on the same point. Of course, if a group of stones contains a

large

number of vacant intersections, it is perfectly safe unless the vacant

space is

so large that the adversary can have a chance of forming an entire new

living

group of stones therein. We now come to the one exception to the

rule that the

players may place their stones at will on any vacant intersection on

the board.

This rule is called the rule of "Ko," and is shown on Plate 6,

Diagram i. Assuming

that it is

White's turn to play, he can play at D 17 and take the black stone

at

C 17 which is already surrounded on three sides, and the position

shown in

Plate 6, Diagram ii,

would then

arise. It is now White's turn to play, and if he plays at C 13,

the white

stone which has just been put down will be likewise surrounded and

could be at

once taken from the board. Black, however, is not permitted to do this

immediately, but must first play somewhere else, and this gives White

the

choice of filling up this space (C 13) and defending his stone, or

of

following his adversary to some other portion of the board. The reason

for this

rule in regard to "Ko" is very clear. If the players were permitted

to take and retake the stones as shown in the diagram, the series of

moves

would be endless, and the game could never be finished. It is something

like

perpetual check in Chess, but the Japanese, in place of calling the

game a

draw, compel the second player to move elsewhere and thus allow the

game to

continue. In an actual game when a player is prevented from retaking a

stone by

the rule of "Ko," he always tries to play in some other portion of

the board where he threatens a larger group of stones than is involved

in the

situation where "Ko" occurs, and thus often he can compel his

adversary to follow him to this other part of the field, and then

return to

retake in "Ko." His adversary then will play in some part of the

field, if possible, where another group can be threatened, and so on.

Sometimes

in a hotly contested game the battle will rage around a place where

"Ko" occurs and the space will be taken and retaken several times. Korschelt states that the ideograph for

"Ko" means "talent" or "skilfulness," in which he

is very likely wrong, as it is more accurately translated by our word

"threat"; but be this as it may, it is certainly true that the rule

in regard to "Ko" gives opportunity for a great display of skill, and

as the better players take advantage of this rule with much greater

ingenuity,

it is a good idea for the weaker player as far as possible to avoid

situations

where its application arises.  Plate 6 There is a situation which sometimes

arises and which

might be mistaken for "Ko." It is where a player takes more than one

stone and the attacking stone is threatened on three sides, or where

only one

stone is taken, but the adversary in replying can take not only the

last stone

played, but others also. In these cases the opponent can retake

immediately,

because it will at once be seen that an endless exchange of moves

(which makes

necessary the rule of "Ko") would not occur. A situation of this kind

is shown on Plate 6, Diagrams iii,

iv, and v, where White playing at

C 8 (Diagram iii)

takes the tree black stones,

producing the situation shown in Diagram iv,

and Black is permitted immediately to retake the white stone, producing

the

state of affairs in Diagram v.

The

Japanese call such a situation "Ute keashi," which means

"returning a blow." It forms no exception to the ordinary rules of

the game, and only needs to be pointed out because a beginner might

think that

the rule of "Ko" applied to it. We will now take up the situation called

"Seki." "Seki" means a "barrier" or

"impasse"—it is a different word from the "Seki" in the

phrase "Jo seki." "Seki" also is somewhat analogous to

perpetual check. It arises when a vacant space is surrounded partly by

white

and partly by black stones in such away that, if either player places a

stone

therein, his adversary can thereupon capture the entire group. Under

these

circumstances, of course, neither player desires to place a stone on

that

portion of the board, and the rules of the game do not compel him to do

so.

That portion of the board is regarded as neutral territory, and at the

end of

the game the vacant "Me" are not counted in favor of either player.

Plate 6, Diagram vi,

gives an

illustration of "Seki," where it will be seen that if Black plays at

either S 16 or T 16 White can kill the black stones in the

corner by

playing on the other point, and if White plays on either point Black

can kill

the white stones by filling the remaining vacancy. Directly below, on

Diagram vii, is shown

the same group, but the

corner black stone has been taken out. The position is now no longer

"Seki," but is called by the Japanese "Me ari me nashi," or

literally "having 'Me,' not having 'Me.'" Here the white stones are

dead, because if Black plays, for instance, at T 4 White cannot

kill the

black stones by playing at S 4, for the reason that the vacant

"Me" at T 1 still remains. The beginner might confuse

"Seki" with "Me ari me nashi," and while a good player has

no trouble in recognizing the difference when the situation arises, it

takes

considerable foresight sometimes so to play as to produce one situation

or the

other. Plate 6, Diagram viii,

shows another group which might be mistaken for "Seki," but here, if

White plays at J 19, the black stones can be killed, further

proceedings

being somewhat similar to those we saw in the illustration of "Go moku

naka de wa ju san te." Plate 7 shows a large group of stones from which

inevitably "Seki" will result. It would be well for the student to

work this out for himself. "Seki" very seldom or never occurs in

games between good players, and it rarely occurs in any game. It is a rule of the game to give warning

when a stone

or group of stones is about to be completely surrounded. For this

purpose the

Japanese use the word "Atari" (from "ataru," to touch

lightly), which corresponds quite closely to the expression "gardez"

in Chess. If this warning were omitted, the player whose stones were

about to

be taken should have the right to take his last move over and save the

imperiled position if he could. This rule is not so strictly observed

as

formerly; it belongs more to the etiquette of the old Japan. The game comes to an end when the

frontiers of the

opposing groups are in contact. This does not mean that the board is

entirely

covered, for the obvious reason that the space inside the groups or

chains of

stones is purposely left vacant, for that is the only part of the board

which

counts; but so long as there is any vacant space lying between

the

opposing groups that must be disposed of in some way, and when it is so

disposed of it will be found that the white and black groups are in

complete

contact. Just at the end of the game there will be

found

isolated vacant intersections or "Me" on the frontier lines, and it

does not make any difference which player fills these up. They are

called by

the Japanese "Dame," which means "useless." (The word

"Dame" is likely to be confusing when it is first heard, because the

beginner jumps to the conclusion that it is some new kind of a "Me."

This arises from a coincidence only. Anything that is useless or

profitless is

called "Dame" in Japanese, but etymologically the word really means

"horse's eye," as the Japanese, not being admirers of the vacant

stare of that noble animal, have used this word as a synonym for all

that is

useless. Therefore the syllable "Me" does mean an eye, and is the

same word that is used to designate the intersections, but its

recurrence in

this connection is merely an accident.)  Plate 7 It is difficult for the beginner at first

to

understand why the filling of these "Dame" results in no advantage to

either player, and beginners often fill up such spaces even before the

end of

the game, feeling that they are gaining ground slowly but surely; and

the

Japanese have a saying, "Heta go ni dame nashi," which means that there

are no "Dame" in beginners' Go, as beginners do not recognize their

uselessness. On the other hand, a necessary move will sometimes look

like

"Dame." The moves that are likely to be so confused are the final

connecting moves or "Tsugu," where a potential connection has been

made early in the game, but which need to be filled up to complete the

chain.

In the Illustrative Game, Number i,

the "Dame" are all given, but a little practice is necessary before

they can always be recognized. When the "Dame" have been filled, and the

dead stones have been removed from the board, there is no reason why

the

players should not at once proceed to counting up which of them has the

greatest amount of vacant space, less, of course, the number of stones

they

have lost, and thus determine who is the victor. As a matter of

practice,

however, the Japanese do not do this immediately, but, purely for the

purpose

of facilitating the count, the player having the white pieces would

fill up his

adversary's territory with the black stones he had captured as far as

they

would go, and the player having the black stones would fill up his

adversary's

territory with the white stones that he had captured; and thereupon the

entire

board is reconstructed, so that the vacant spaces come into rows of

fives and

tens, so that they are easier to count. This has really nothing to do

with the

game, and it is merely a device to make the counting of the spaces

easier, but

it seems like a mysterious process to a novice, and adds not a little

to the general

mystery with which the end of the game seems to be surrounded when an

Occidental sees it played for the first time. This process of

arrangement is

called "Me wo tsukuru." It may be added that if any part of the board

contains the situation called "Seki," that portion is left alone, and

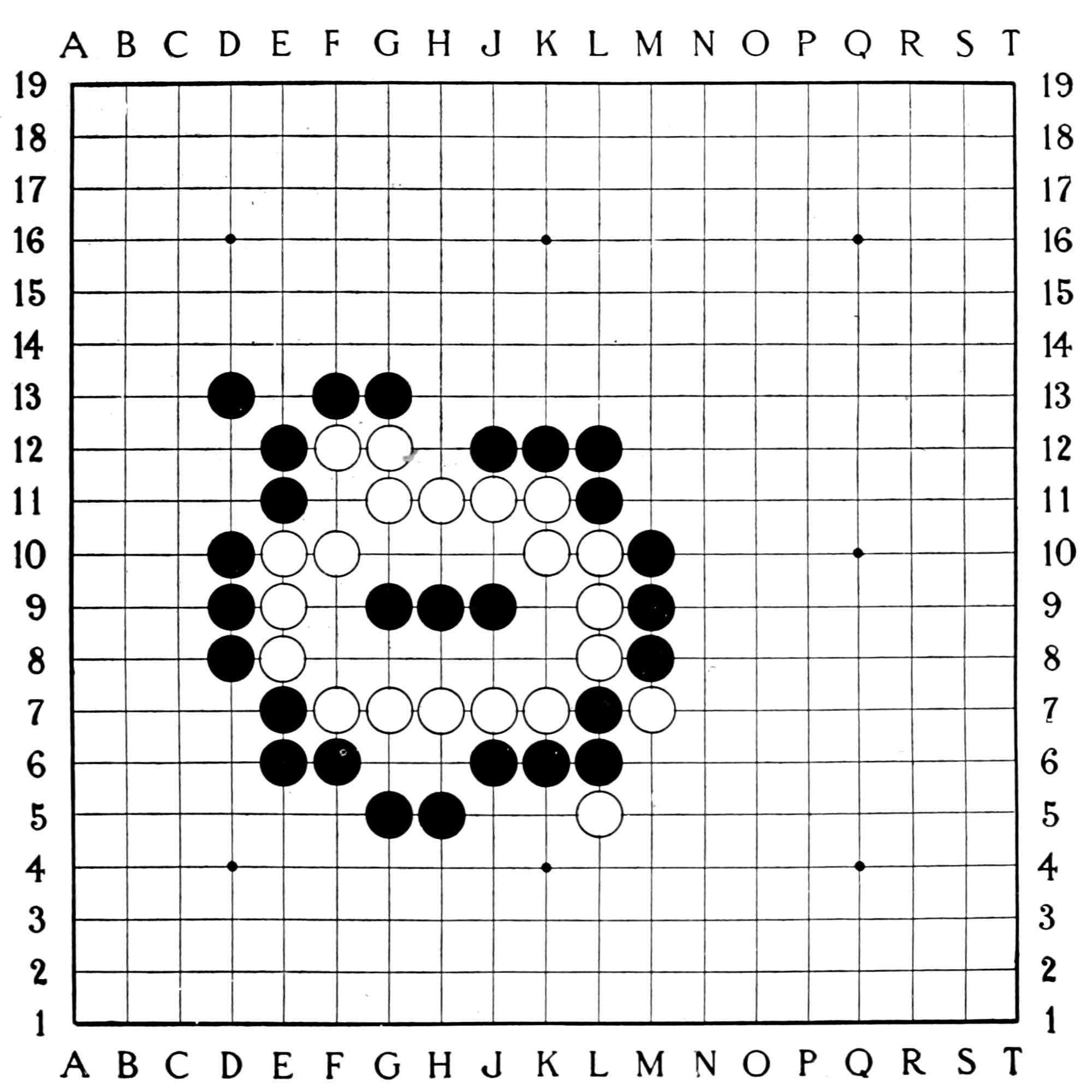

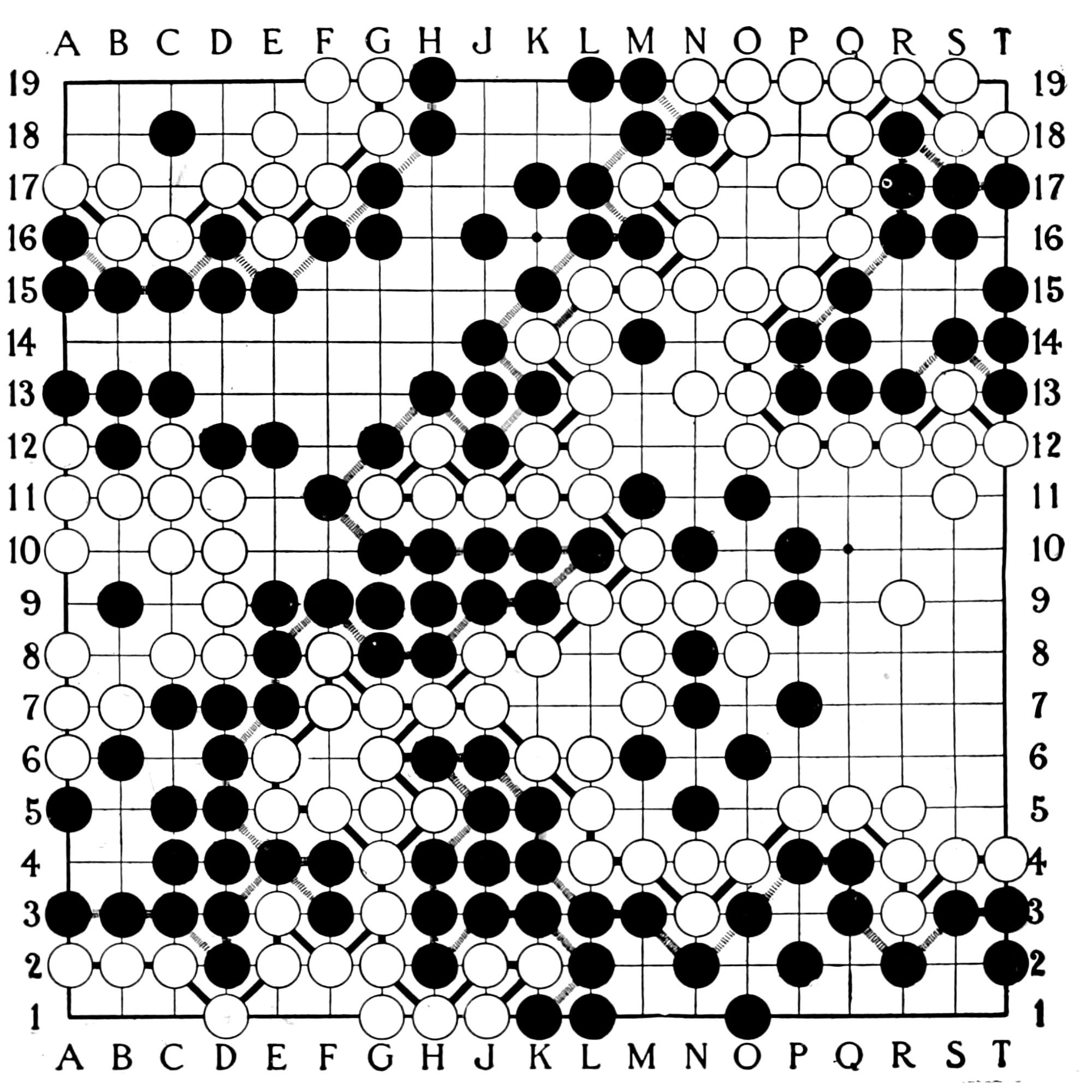

is not reconstructed like the rest of the board. Plate 8 shows a completed game in which

the

"Dame" have all been filled, but the dead stones have not yet been

removed from the board. Let us first see which of the stones are dead.

It is

easy to see that the white stone at N 11 is hopeless, as it is cut

off in

every direction. The same is true of the white stone at B 18. It

is not so

easy to see that the black stones at L and M 18, N, O, P, Q and

R 17,

N 16, and M and N 15 are dead, but against a good player they

would

have no hope of forming the necessary two "Me," and they are

therefore conceded to be dead; but a good player could probably manage

to

defend them against a novice. It is still more difficult to see why the

irregular white group of eighteen stones on the left-hand side of the

board has

been abandoned, but there also White has no chance of making the

necessary two

"Me." At the risk of repetition I will again point out that these

groups of dead stones can be taken from the board without further play.

Plate 9 shows the same game after the dead

stones

have been removed and used to fill up the respective territories, and

after the

board has been reconstructed in accordance with the Japanese method,

and it

will be seen that in this case Black has won by one stone. This result

can be

arrived at equally well by counting up the spaces on Plate 8, but they

are

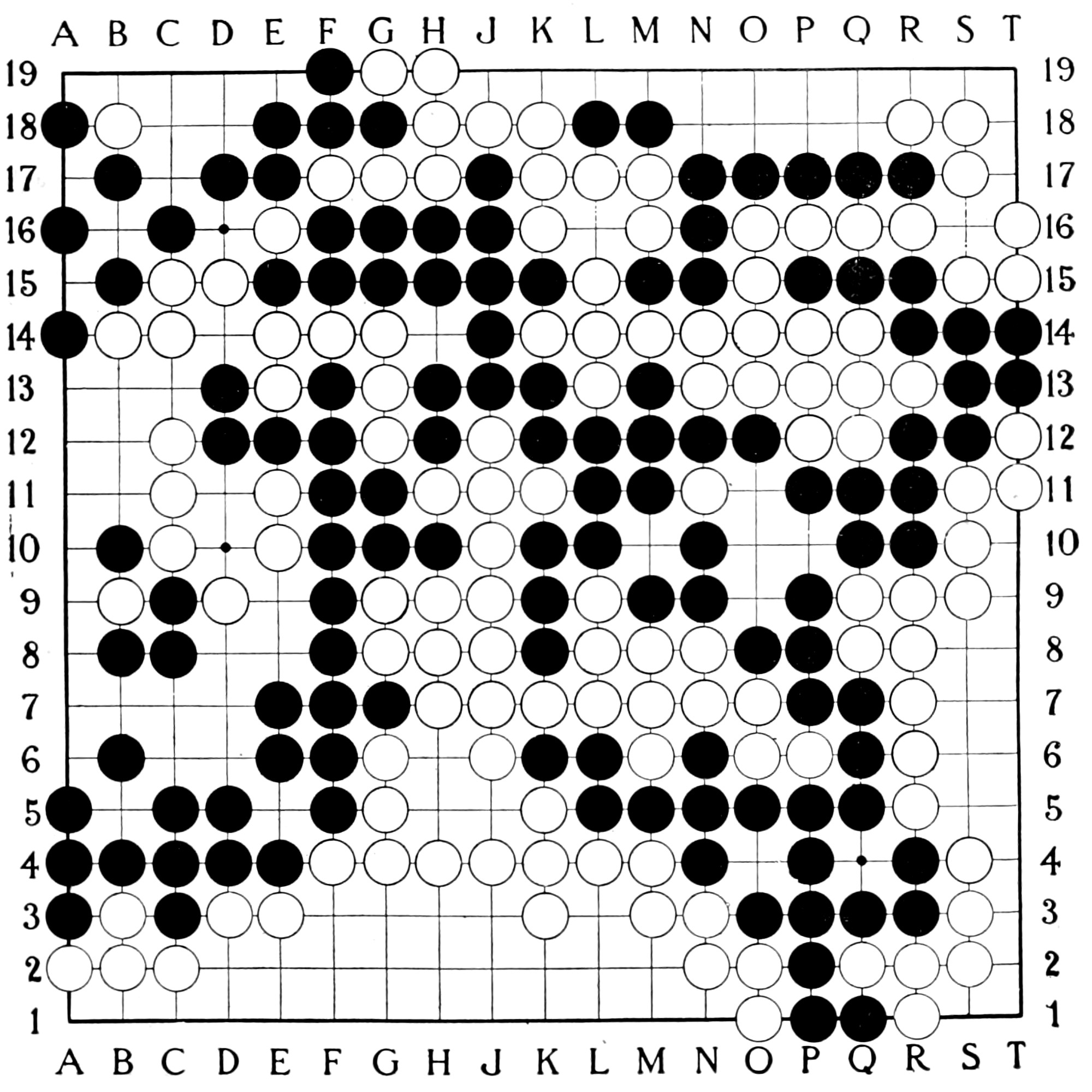

easier to count on Plate 9, after the "Me wo tsukuru" has been done. Plate 10 shows another completed game.

This plate is

from Korschelt, and is interesting because it contains an instructive

error.

The game is supposed to be completed, and the black stone at C 18

is said

to be dead. This is not true, because Black by playing at C 17

could not

only save his stone, but kill the four white stones at the left-hand

side.

Therefore, before this game is completed, White must play at C 17

to

defend himself. This is called "Tsugu." On the left-hand side of the

board is shown a white group which is dead, and the method of reduction

of

which we have already studied in detail. On the right side of the board

are a

few scattering black stones which are dead, because they have no chance

of

forming a group with the necessary two "Me." The question may be

asked whether it is necessary for White to play at C 1 or E 1

in

order to complete the connection of the group in the corner, but he is

not

obliged so to do unless Black chooses to play at B 1 or F 1,

which,

of course, Black would not do. On Plate 11, this game also is shown as

reconstructed

for counting, and it will be seen that White has won by two stones.

Really this

is an error of one stone, as White should have played at C 17, as

we have

previously pointed out.  Plate 8  Plate 9  Plate 10 Sometimes at the end of the game players

of moderate

skill may differ as to whether there is anything left to be done, and

when one

thinks there is no longer any advantage to be gained by either side, he

says,

"Mo arimasen, aru naraba o yuki nasai," that is to say, "I think

there is nothing more to be done; if you think you can gain anything,

you may

play," and sometimes he will allow his adversary to play two or three

times in succession, reserving the right to step in if he thinks there

is a chance

of his adversary reviving a group that is apparently dead. No part of the rules of the game has been

more

difficult for me to understand than the methods employed at the end,

and

especially the rule in regard to the removal of dead stones without

actually

surrounding them, but I trust in the foregoing examples I have made

this rule

sufficiently clear. Moreover, it is not always easy to tell whether

stones are

dead or alive. There is a little poem or "Hokku" in Japanese, which

runs as follows:

We now come to the question of handicaps.

Handicaps are

given by the stronger player allowing the weaker player to place a

certain

number of stones on the board before the game begins, and we have seen

in the

chapter on the Description of the Board that these stones are placed on

the

nine dotted intersections. If one stone is given, it is usual to place

it in

the upper right-hand corner. If a second stone is given, it is placed

in the

lower left-hand corner. If a third stone is given, it is placed in the

lower

right-hand corner. The fourth is placed in the upper left-hand corner.

The

fifth is placed at the center or "Ten gen." When six are given, the

center one is removed, and the fifth and sixth are placed at the left

and

right-hand edges of the board on line 10. If seven are given, these

stones remain,

and the seventh stone is placed in the center. If eight are given, the

center

stone is again removed, and the seventh and eighth stones are placed on

the

"Seimoku" on line K. If the ninth is given, it is again placed in the

center of the board.  Plate 11 Between players of reasonable skill more

than nine

stones are never given, but when the disparity between the players is

too

great, four other stones are sometimes given. They are placed just

outside the

corner "Seimoku," as shown on the diagram (Plate 12), and these extra

stones are called "Furin" handicaps. "Furin" means "a

small bell," as these stones suggest to the Japanese the bells which

hang

from the eaves at the corners of a Japanese temple. When the disparity

between

the players is very great indeed,

sometimes four more stones are given, and when given they are placed on

the

diagonal halfway between the corner "Seimoku" and the center. These

four stones are called "Naka yotsu," or "the four middle

stones," but such a handicap could only be given to the merest novice.  Plate 12 We have now completed a survey of

all the actual

rules of the game, and it may be well to summarize them in order that

their

real simplicity may be clearly seen; briefly, they are as follows: 2. The stones are

placed on the intersections and on any vacant intersection the player

chooses

(except in the case of "Ko"). After they are played they are not

moved again. 3a. One or move stone which are compactly

surrounded by the stones of the

other side are to be taken are at once removed from the board. b. Stones which, while not actually

surrounded can inevitably surrounded, are dead,

and can be taken

from the board at the end of the game without further play. c. Taken or dead stone are used to fill up the adversary's territory.

It is not possible to imagine a game with

simpler rules,

or the elements of which are easier to acquire. We will now turn our attention to few

considerations

as the best methods of play, and of certain moves and formations which

occur in

every game, and also to the manes which in Japanese are used to

designate these

things. |