| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

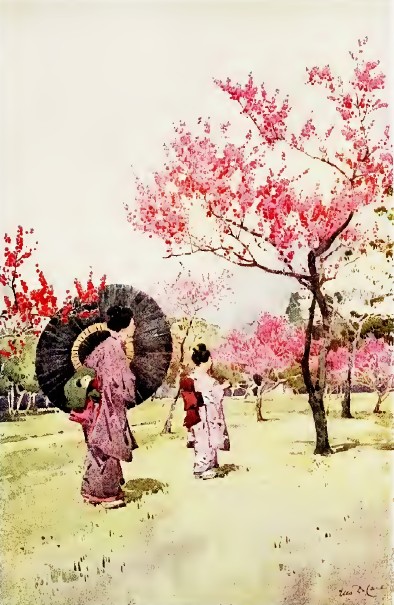

VIII PEACH BLOSSOM THE peach blossom has never attained the fame in Japanese art, or among their poets, that its classical predecessor the plum, or its successor the cherry of patriotic fame, has been honoured with; but it is none the less beautiful for that reason, and its blossoms excel those of the plum in size, richness, and colouring. Towards the end of March the first flowers of the peach-trees will be opening, although long before this time, branches closely covered with the bright-pink buds will have been among the flowers offered for arrangement on the tokonoma, as in the warmth of the house (though surely there seems to be very little warmth in a Japanese house all through the long cold March days) the buds will quickly open and last in beauty for many days. These will be branches of the early bright pink variety, but it is not until the beginning of April that the large flowered pure white, double and semi-double flowers of every shade of pink, and even a deep crimson of a remarkably beautiful tone, will be in their full glory, and it is hard to understand why this splendid blossom should be comparatively neglected and relegated to secondary rank by the artist as a decorative motive and material.

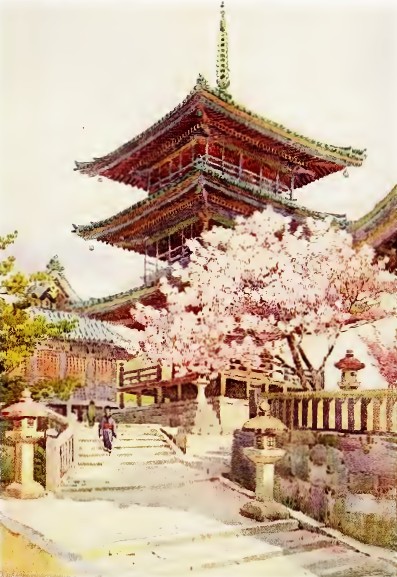

Peach Blossom The less severely artistic, who find enjoyment at any spot where blossom and colour are to be seen, will visit Momoyama (Peach Mountain) in crowds during the first week in April, and the narrow streets leading up to the hill will be gay with visitors, and among the orchards the little temporary tea sheds will be set out for their comfort and refreshment. So yet another "Feast of blossom" will be celebrated. The trees may perhaps lack some of the grace of the old gnarled plum-trees, and they do not appear to have such a long life, as never did I hear of any very celebrated old specimen trees, but rather groves or orchards of younger trees, which no doubt, in order to make them bloom freely, receive drastic treatment at the hand of the pruner. Very lovely are these groves of peach-trees, and surely they must have found favour in the ancient days, as on Momoyama stood Hideyoshi's palace, the grandest ever built in Japan, whose spoils in the shape of gold screens and fusuma adorn half the temples in Kyoto. The peach orchards of Soka-no-momoyama at Senju are a favourite resort of the Tokyo holidaymakers, who make annual pilgrimages to do honour to the peach blossoms, and parties sit feasting on the matted benches; here and there perhaps a group discussing the politics of the capital, or a solitary poet composing a hokku on the peach blossom, or a family party; and there the little boys and girls, decked out in their brightest-coloured kimonos and obis in honour of the holiday, will be listening with rapt attention to the fairy-story of Momo Taro, who jumped out of a large peach-stone. To the older children it is an old story, for every Japanese child has listened at bedtime to the tale of Momo Taro told by its mother, but for the little ones this may be their first year of "peach-viewing" and understanding, and their eyebrows will rise in amazement when they hear the history. "Once upon a time," the story says, "there was an old man and an old woman; the old man went up the mountain to collect dried brushwood, and the old woman went to the river to wash clothes," and there one of the older boys will interrupt, I am sure, saying, "A big peach came down the river; and Momo Taro jumped out of the stone when the old woman brought it home and cut it open, didn't he?" So there is not a child in Japan who does not know the history of Momo Taro, the children's hero, who made an expedition into the Oniga Shima (Devil's Island) followed by his dog and monkey servitors. It would be no surprise to them to see even a fat little boy like themselves spring out of the end of the fruit, so the Japanese boys adore the peach; and the little girls share their affection for it, as it is always associated in their mind with their own especial festival. During the season of the early peach blossoms (on 3rd March) the Girls' Festival (Jomi-no-sekku) is celebrated throughout Japan; it is also called the Feast of Dolls (Hina Matsuri), and the Peach Festival, for no Girls' Festival is complete without some branches of peach blossom in the vase on the tokonoma. This day is eagerly looked forward to by every little girl in Japan, from the highest to the lowest in the land, for every house possesses its little store of dolls, only to be brought out and exhibited with due pomp and ceremony on this one day in the year. In the houses of the rich, the Dairi Hina — tiny models of people and their belongings — the dolls will be dressed in gorgeous silk, and their accessories mostly made of priceless lacquer. The whole ancient Japanese Court in miniature there may be: these will all be displayed on the tokonoma of the guest chamber, possibly on a piece of brocade as gorgeous as the peach blossom in colour. And there you will see an emperor and an empress and a set of Court musicians; before them the most elaborate dinner sets in ancient form; beside them there will be the Sho kudai (lamp-stand with paper shade) with pictures of peach blossom on it. The little daughters of the house will surely look to our eyes only like larger dolls, with their delicate coloured silk crepe kimonos and stiff brocade obis standing out like great butterflies on their backs, their hair carefully dressed according to their age, the older ones with just a little powder on their tiny inscrutable faces, acting as hostesses with all the solemn grace of their mother, offering to the guests tiny cups of tea and little fairy cakes shaped and coloured like peach petals. This girls' day is one of the prettiest sights in Japan, and yet there is no record how far back the festival originated, though it is believed to date from a thousand years ago. In the days of the Tokugawa feudal régime — days of perfect peace and prosperity — it became a very expensive festival, and great sums were expended on these toy Dairi Hina, so it is not surprising that they were handed down as heirlooms in families only to be displayed once a year, or sometimes a bride. scarcely more than a child herself, would take her set of favourite dolls with her to her husband's house, so that her little daughter might perhaps some day also use them to celebrate the Girls' or Peach Festival. So in Japan the peach is truly the children's tree. Momo, meaning a hundred, is considered "emblematic of longevity and perfection," which probably is the origin of the story of Seibo the fairy who governed the western realm of China. She gave some peaches to the Emperor Butei, and told him that that variety of peach only bore fruit once in three thousand years, and he would live eternally from the fruit's heavenly influence. If we could only get such peaches to-day? Perhaps it might do as well to eat a common peach from the market and dream, if possible, of the beauty of eternal life and be happy. In Chinese art the peach blossom seems to rank higher than it does in Japan, and a very favourite subject with Chinese artists is an ox in a peach orchard. The finest pot-grown peach-trees I ever saw were in China, their gnarled stems looking truly a thousand years old, their branches trained and bent or merely drooping like a willow, covered with the clear pink blossoms. The trunks of these fine old trees may have been three or four feet high; but in Japan it is possible to procure a little plant for perhaps 25 sen (about sixpence) whose branches are so tightly packed with blossoms it is impossible to see a trace of even the bark between them — a perfect little tree in a delicate green or mottled blue porcelain pot. I could not help thinking what pleasure such trees would give in England, but apparently it is only the Japanese who know the real secret of growing them, the exact shoots to leave and which to cut away, to ensure this wealth of blossom. I felt in England my little peach-tree would only flower here and there, and its beauty would be lost. There is a popular saying in Japan, Momo kuri san nen, kaki hachinen, meaning "three years for peach and chestnut, eight years for persimmon." The peach-tree is of rapid growth; this fact is proved by there being a variety called Issai momo, because it blooms the first year of its growth, and bears fruit the second. There is Futairo momo, the two-coloured peach, whose blossoms are mingled red and white in colour, single and double in petals; there is Hiku momo, or chrysanthemum peach, as its blossoms are the shape of a chrysanthemum flower, in clusters of twelve or thirteen; the camellia peach and many others with fancy names from their supposed resemblance to their god-father. The native peaches do not bear good fruit, and the better varieties have been introduced from America, but up to now with only moderate success. There are no good eating peaches in Japan; this may be the fault of the climate, possibly the hot damp summer does not suit them, or the cultivation may be at fault; but when their blossoms provide such a feast of colour and beauty it seems altogether too unromantic and too material to worry over the texture and flavour of the fruit.  The Pagoda, Kyomidzu |