| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

VII PLUM BLOSSOM In Japan the flower year begins earlier than in Europe, and while the snow is still lying deep on the ground in the northern provinces, in warm and sheltered districts the Ume or plum blossom will clothe the trees with flowers as white as the snow. But in the country round Kyoto or Tokyo it is not until the end of February or the first days of March that the pale pink buds of the plum blossoms will be opening, and there will come a whisper through the air that in a few days the beloved ume-no-hana will be in all its glory. The plum is one of the favourite, perhaps the favourite tree of the Japanese, so in early March, when the sunny days will remind us that spring is coming, though the cruel frosts and snow showers at night will warn us that winter is not yet gone, every passer-by seems to be talking of ume, discussing probably where the earliest blossoms are to be found, and when the first flower-viewing excursion of the year is to take place. The

Japanese are essentially a flower-loving people; in no other country

would you find whole families, old and young, rich and poor, tramping

for miles in the hot sun or through the drenching rain to indulge in

their favourite pastime of flower-viewing. Showing how universal is

this custom of special flower-viewing excursions, there is even a

phrase in the Japanese language, hana

miru meaning to view

flowers.  Viewing the Plum Blossoms

The earliest plum blossom, known as the no-ume, is a somewhat uninteresting little white flower, not unlike the wild sloe in our English hedgerows, and I was beginning to think the celebrated plum blossom of Japan was an overrated flower, when gradually its full beauty dawned upon me. The deep pink buds of the later varieties opened into pale blush coloured blossoms, and the crimson buds of the kobai — the most cherished of all — burst into a cloud of brilliant pink flowers; others there were, pale lemon coloured or large pure white, in great variety. The plum-tree is especially valued for its age, and a venerable tree, its stems covered with grey lichen, though its flowers may be poor in quality, will be more prized than a young tree with the most brilliant coloured blossoms. Tsukigase, in the province of Shima, a little village famous for the beauty of its plum-trees, is one of the first places to be visited by that large proportion of the inhabitants of Kyoto who seem to spend most or all their days during the spring months in a never-ending round of sight-seeing and flower-viewing. In the month of March the village is made gay for the reception of these holiday-makers, and undaunted by the bitter winds and vicious scuds of snow which mingle with the falling petals of the ume, they will spend long hours in quiet admiration of the mass of blossom which appears to fill the whole valley with a pink and white haze; for over two miles the trees clothe the banks of the river Kizu. Countless tea-stalls are prepared for the guests, light bamboo structures adorned with a few printed linen curtains in soft harmonious colouring, and innumerable paper lanterns suffice for the preparation of a flower feast. Each night, or at the approach of rain, the little maids will carefully pack away the matted benches and these frail decorations under the thatched root to be brought forth on the morrow or when the storm has cleared. The Japanese regard the flower of the plum with a peculiar reverence, and their feeling for it always seems to be touched with some mysterious sense of sorrow, which perhaps accounted for the fact that these plum-blossom feasts never seemed to attain to the same merry boisterous revels held at the time of the cherry  The Gate of the Plum Garden blossom. The people were more quiet and sober in their demeanour; at first I thought their spirits were frozen by the cold, but even the endless drinking of tea and tiny cups of saké did not seem to thaw them, and often whole parties, wrapped in their outer winter kimonos, would sit in silent contemplation of the blossoms, warming their hands over that Japanese apology for a fire — an hibachi — consisting merely of a pot of charcoal. In old days the plum blossom was their ideal of purity, an ideal which some attempted to emulate in their lives. The same feelings prevail in China, if we may judge from the poets. This, to be sure, is not surprising, inasmuch as Japan took her literature, like most other things, from the Chinese. The early poems of both countries are much alike, and among them both are many ume poems, as the Japanese call them, extolling the beauty and charm of the plum blossom, which ranks as the poet's own flower. Mr. Kango Uchimura has written an ode to it in prose, which contains the following passage: —

While Spring was still cold I knew that it was at hand by your flowering. You are not Spring, but the prophet of Spring. The cherry blossom is Spring, the iris and the wistaria; but, as each of these has its own season, the gods sent you to keep green our hope of Spring. I do not say I love you, rather I fear you; you are too dignified; you blossom alone on the branches with no green leaves to bear you company. I do not call you beautiful; your scent is too keen, your petals too stiff. No one will ever sing or dance beneath your boughs. You are the prophet Jeremiah; you are John the Baptist. Standing before you I feel as though in the presence of a solemn master. Yet by your appearance I know that Winter has passed, and that the delightful Spring is at hand. The herald of Spring, you denounce the tyranny of Winter. Your face is stern, but your heart is soft. It is easy to misunderstand you, for, though the daughter of Spring, you wear the garb of a man the man ordained to break the power of cruel Winter.

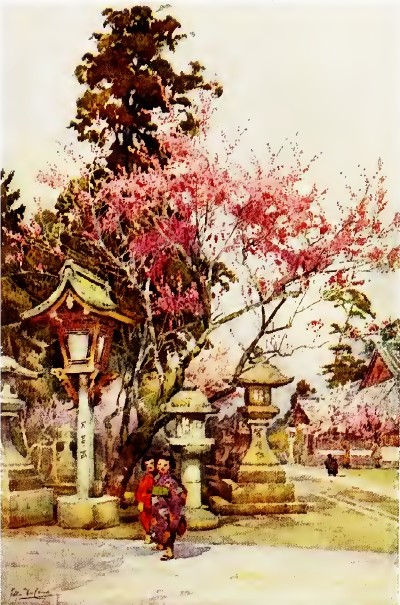

Two famous men in olden days were particularly associated with the flowers of the plum. One of these was Kajiwara Genda Kagesuge, a great warrior of the twelfth century, who always went into battle carrying in his quiver fresh branches of the blossom, to which, so says the legend, he was indebted for his splendid courage. The other was Sugawara No Michizane, the minister of the Emperor Ude. The Kwampaku Tokihira, wishing to be quit of the sage's wisdom, sent him into a sort of honourable exile in the island of Kyushu, where he died in 908. After his death came a great reaction in his favour. He was canonised under the name of Tenjin, or the Heavenly god, and to this day he is venerated by all men of letters as their patron saint; in every school the twenty-fifth day of each month is kept as a holiday, and every year on the twenty-fifth of June a great festival is held in his honour. His life is dramatised in the popular play Sugawara Tenjin Ki, and all over the land shrines dedicated to his memory rise from groves of plum-trees. One of the most famous and beautiful of these is the temple of Kitano Tenjin at Kyoto, which has provided subjects for several of the illustrations in this volume. In the inner court of the temple near the splendid two-storied gateway of the Sun, Moon, and Stars stands a large tree of the bright pink blossom, and it would be difficult to find a more beautiful setting for the tree than the background of grey wooden buildings, of which the decorations have been toned by the hand of time into soft mellow hues. In the outer grounds the trees have a background of giant cryptomerias, with long avenues of stone lanterns — votive offerings of every conceivable shape and size — small shrines, and two great granite torii, the plain yet majestic gateways which guard the entrance to all Shinto temples. When the trees are in all their glory the flower-viewing parties wander through the grounds in silent admiration, down to the little ravine outside the temple grounds, where the snow-white blossom fills the little valley and clouds of petals fall into the brook below, to be carried away down the stream like drifts of foam. Here may be seen a poet of the old school rapt in thought, composing an ode to the blossom and the nightingale. It is a pretty fancy much honoured in Japan, the plum blossom, the poet, and the nightingale making, they say, the world of beauty complete. For no Japanese ever thinks of the plum blossom apart from the nightingale — which, it should be observed, is not the bird of Keats's poem, singing of summer in full-throated ease, but a little light-winged creature whose favourite haunt is among the flowering branches of this tree. In Japanese legends the plum blossom and the nightingale are inseparable companions, and represent the two spirits of the awakening spring when the mists of winter first begin to roll away. There is a story, for instance, of the daughter of the poet Kino Tsurayuki, who lived in the days of the Emperor Murakami, in the tenth century. From time immemorial a single plum-tree bad always stood before the south pavilion of the Imperial Palace at Nara, and when at some period of this Emperor's reign the tree died, messengers were despatched in hot haste to find one worthy to replace it. One was found in the garden of the poet aforesaid, a fine tree with crimson blossoms belonging to his daughter, who was most reluctant to part with her favourite. However, there was, of course, no help for it, and the tree was sent off to the palace grounds with some verses fastened to it, which run thus in Mr. Brinkley's translation —

The Emperor, struck with the graceful sentiment of the verses, made inquiries as to the writer, and finding that she was the daughter of his favourite poet, ordered the tree to be returned to her.

The Time of the Plum Blossoms Throughout Japan there is scarcely a district to be found without orchards and groves or temple grounds where the flower-seeker can go to greet spring and the ume, but the people of Tokyo are singularly fortunate in their plum orchards. One of the most famous and beautiful is at Sugita, a charming little village nestling by the bluest of waters, near Yokohama, where a thousand trees have stood for upwards of a century, displaying their blossom every spring to admiring eyes from all the country round. Here there are six special kinds of the tree, and their fancy names mark the different characters of the flowers, the Japanese being very clever at finding characteristic names for flowers and trees. The Gwario Bai, or Recumbent Dragon Tree, is the most famous of these, being indeed the most notable thing in the outskirts of Tokyo. Some fifty years ago there grew a wonderful tree of vast age and strange shape, its branches having ploughed up the ground and thrown out new roots in no fewer than fourteen places, thus naturally covering an extensive area. The name of Gwario Bai was given to the tree by old Prince Rekko, who planted the groves in Tokiwa Park in 1887, a piece of forethought highly appreciated by many visitors to this day. The Shogun (or Generalissimo) of that day also paid a visit to the spot, and made the tree Goyobaku or the Tree of Honourable Service, in return for which gracious act of condescension the fruit was presented to him every year. All these honours, however, could not save it from a natural death when its time came; in its place now flourish a number of much less interesting trees, which nevertheless bear the same name, and apparently the same reputation, as their predecessor the Dragon of the prime. Not far from the Gwario Bai is the orchard of Kinegawa, which can boast an honoured name too, for here the poets come, and you may see perhaps a hundred slips of paper, containing uta or hokku (seventeen-syllabled) poems, fluttering from the branches. Perhaps here, too, we may find a family party, the mother with the youngest child tightly strapped on her back, its tiny shaven head hardly showing above the wadded quilt which is wrapped closely round it; a little mite of a very few summers, tottering unsteadily on its clogs, clasping a branch of the natural tree adorned with paper blossoms, from which floats a streamer with some strange device, or any of the countless toys which go towards the making of a holiday; and only a few years older a little solemn-faced maiden, whose black beady eyes will glisten with wonder when she is told that she is called Ume san after the snow-white blossom at which she has been gazing with awe and admiration. Ume is a common name among Japanese women; they connect it with the ideas of virtue and sweetness, and they are taught to keep the name unspotted during life and to leave it fair after death, even as the scent of the plum blossom smells sweet in the darkness. The following verses are from Piggot's Garden of Japan: — Home

friends change and change,

Years pass quickly by; Scent of our ancient plum-tree, Thou dust never die. Home friends are forgotten; Plum-trees blossom fair, Petals falling to the breeze Leave their fragrance there. Cettria's fancy, too, Finds his cup of flowers, Seeks his peaceful hiding-place, In the plum's sweet bowers. Though the snow-flakes hide And thy blossoms kill, He will sing, and I shall find Fragrant incense still.1 Ginsekai is yet another orchard in the neighbourhood of Tokyo, its name signifying Silver World, and on a moonlit night in spring you would say that never was a place more aptly named, if you saw the forest of white blossoms rising out of the snow-clad landscape. There are some pretty verses on the sight, which run thus in English: — How

shall I find my ume

tree?

The moon and the snow are white as she. By the fragrance blown on the evening air Shalt thou find her there. It is true that the white varieties of plum blossom have nearly all a most delicious and delicate scent, but the red varieties are quite devoid of any fragrance. The plum is known as one of the Four Floral Gentlemen, the others being the pine, the bamboo, and the orchid. It has flourished in China from time immemorial, where it is known as the Head of the Hundred Flowers, because it is the first to bloom, and it was probably imported from that country through the medium of Korea into Japan. Even that learned botanist the late Dr. Keisuke Ito could not say where the plum-tree first flowered in Japan, nor can any one say with certainty whether ume is a Chinese or a Japanese word. Kakimoto no Hitomaro, who lived about the end of the seventh century, was probably the first to celebrate the plum blossom in his verse; and it may be said to have taken rank as a national flower when the Emperor Kwamaru (782-806) planted it before his palace when he moved his capital from Nara to Kyoto. In those days the word, flower meant the flower of the plum, just as the word mountain meant Hiei san, but it was dethroned from its pride of place when the Emperor Murakami planted the cherry-tree in its stead, and though the plum still stands first with the men of mind, the cherry-tree has ever since been the popular favourite. That the latter is most beautiful cannot be disputed; but for purity of outline, fragrance, and that touch of sadness, which the Japanese profess to find in it, the bloom of the plum is still unrivalled.

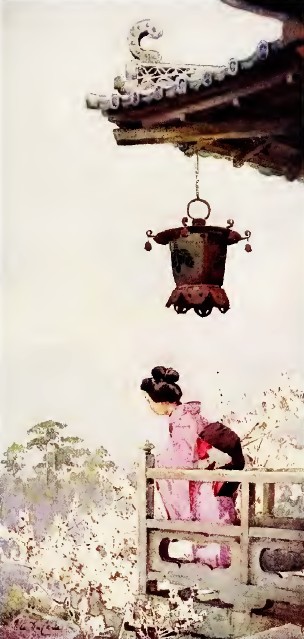

Plum Blossom and Lanterns There are upwards of three hundred and fifty specimens of the plum, white, pale and bright pink, or even red in colour, single or double in form. Of these the more important are: Yatsu buse ume, which derives its name from bearing eight fruits, the blossoms having from two to eight stamens, the word signifying eight tassels; only two or three of these, however, ripen fully, and they are unfit for eating. The Bungo ume grows in the Bungo province of the island of Kyushu; its fruit is large and can be eaten uncooked, though the Japanese prefer it pickled or candied. The fruit of the Ko ume, celebrated for the beauty of its bright pink blossom, is no bigger than the tip of one's thumb, but has a delicious flavour. Toko no ume is a late fruit, clinging to the branch even when fully ripe, whence its name Toko, meaning eternal. The flowers of Suisen ume have six petals, round or long in shape. Hava ume, or the early plum, blooms at the winter solstice. In no other country does the culture of plants go hand in hand with art as it does in Japan; not only in the case of their dwarf trees, marvels of horticultural art, but even the trees which are necessary for the scenery of their landscape gardens have to conform to the rules which govern the entire art of the country. I remember being shown with great pride by the owner of a tiny garden his one solitary plum-tree, the pride of his garden in those cold March days. It stood leaning over a miniature rocky precipice, down which tumbled a diminutive cascade; old and venerable it looked, having endured ruthless pruning, and only a few large single blossoms clothed its branches. I expressed surprise and some regret that it did not bear more blossoms, and then it was explained to me that many of the buds had been removed, as otherwise the thick cloud of flowers would have hidden the outline of the branches; this was a flight of æstheticism to which I could not rise, and I felt I should have preferred to see the tree bearing its full burden of blossom. This practice of disbudding is also occasionally carried out with old specimens of dwarf plum-trees when it is considered that a wealth of blossom would hide the growth of the little tree, which by careful training has after years of patience rewarded the owner by conforming to the desired shape laid down by the canons of art. These little trees are in great demand at the close of the year, for hardly a house in the land is without a tiny tree of ume, to bring luck at the opening of another year; so during November and December, when their pale-pink buds are fast swelling, they are tended with the greatest care, brought into the sun during the day, plentifully watered at sundown, and sheltered from all cold winds. Thus they flower sometimes as early as New Year's Day, to the intense pride and joy of their owners. The hearts of the plum-trees, say the Japanese, are a thousand years old, and yet young as the hopes of Japan.

1 Cettria, the nightingale. |