| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

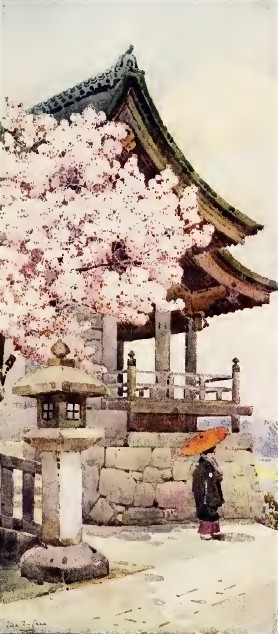

IX. CHERRY BLOSSOM JAPAN is often called "The Land of the Cherry Blossom," and it is true that for centuries their Sakura-no-hana has been the favourite flower of the Japanese. The refinement and grace of its beauty appeals to them so intensely, that the month of April, the time of the cherry blossom, might almost be regarded as a national holiday throughout the country; and can one wonder that a whole nation should forget for a time their work and domestic worries in the innocent enjoyment of sitting under the flower-laden trees? In contrast to the simple growth of the plum-tree, the blossom of the cherry covers the whole tree in rich profusion, the branches bending under the weight of its luxuriance, scattering a rosy shower of petals as they sway in the spring breezes. Lafcadio Hearn, in his Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, says: "When, in spring, the trees flower, it is as though fleecy masses of clouds, faintly tinged by sunset, had floated down from the sky, to fold themselves about the branches. . . . The reader who has never seen a cherry-tree blossoming in Japan cannot possibly imagine the delight of the spectacle. There are no green leaves; these come later; there is only a glorious burst of blossoms, veiling every bough and twig in their delicate mist; and the soil beneath each tree is covered deep out of sight by fallen petals, as by a drift of snow." Unlike many of the favourite flowers of Japan, which are only grown in certain districts, and might bloom altogether unobserved if one did not make a special search for them, the cherry is so lavishly planted throughout the Empire that it would be impossible to find any part of the country without some display of the blossom. The full beauty of the cherry is short-lived, and, almost before one has realised the transformation of the whole landscape, brought about by this wonderful flower, with the help of the glorious April sunshine, a heavy rain-shower or sudden squall will scatter the petals like snow before the wind, and nothing will remain but the young brown leaves and the carpet of fallen petals beneath the trees. We are told of Fujiwara-no-Narinori, of the twelfth century, who prayed to the god Taizanfukun for the prolongation of the glory of his beloved cherry blossom. Fujiwara had planted over a hundred of the trees in his garden, and had, on that account, been named Sakura Machi by the people. It is said that the gods answered his prayer, and allowed the trees to remain in flower for twenty-one days. Another legend tells of Minamoto-no-Yoshiyo the warrior, who was despatched to fight with Abeno-Sadato of Oshu. While on his way to the enemy's camp, he passed through groves of falling cherry blossoms, and was struck with lamentation over the changing of nature. His poem remains to this day, and after his death a monument was erected to his memory, on the spot where his inspiration seized him. It is difficult to decide in which surroundings the cherry blossom shows to best advantage. In the groves or orchards devoted entirely to the sakura, where the flower-laden trees will surround one on all sides, there will be cherry blossom, and nothing but cherry blossom almost as far as the eye can reach. From every tree will hang rosy-red lanterns, or a poetical name and inscription will flutter in the breeze, while crowds of visitors wander through the grounds; children clapping their chubby hands in sheer enjoyment of the blossoms, tumbling, in their haste to find fresh treasures, over their gay-coloured kimonos, which, with their gorgeous obi, have been put on to-day for the first time in the honour of spring, and the sakura. Perhaps you might prefer to see the trees in a setting of red-brown maples and deep-green pines, in a wilder and more natural state, where one of the many fast-flowing rivers will hurry along beneath the overhanging boughs, carrying away great drifts of fallen petals; or, again, by the sea-shore, where a few great trees, high up on the cliffs, away from all danger of salt sprays, will make a glorious foreground for the rugged coast-line and the wide stretch of sea beyond. But surely there is no more beautiful setting for the trees than the old temple buildings, with their wooden structures toned by countless ages. A great weeping cherry-tree will stand as a sentinel at the gateway, or a little tree laden with rosy blossoms will guard a tiny shrine. All through the bright spring days, thousands of sight-seers will climb the stone steps of the temple of Kyomizu — or Good Water — in Kyoto, and wander through the buildings to the woods beyond. From the terrace they gaze down upon the grove of cherry and maple trees in the valley below, and then away over the grey roofs of Kyoto and the plain beyond, to Osaka, hidden in the morning mists, or to Arashiyama, whose groves will assuredly be visited in due time by these untiring holiday-makers. At every turn a new beauty wipes out the remembrance of the last, and fills our soul with sadness, that nature will not stand still for awhile and give us leisure to enjoy what we know will be here to-day and gone to-morrow. Already the early single flowers are fading and falling; every gentle breath of wind sends a fresh shower of the thin transparent petals to the ground. To-morrow the heavy clusters of the double pink blossoms will have lost their freshness, and will be hiding their glories under the brown leaves that seem to unfurl and grow while we look at them. Last, and perhaps best of all, will come the double white blossom, whose buds are now hanging in pink clusters, and whose beauty will linger until the close of the "cherry month."

A Buddhist Shrine Maruyama Park in Kyoto has a great display of cherry blossom; an enormous drooping cherry of great age, which has taken its name of Gion sakura from the Gion temple adjoining, stands in the middle of the park, and thousands of people come to gaze at it every year when it is in flower. Towards the end of March, the park, which has been bleak and deserted all the winter, becomes a scene of bustle and activity. Temporary tea-houses are put up on every available space, hung with innumerable lanterns, and gaily-coloured curtains, most of these being painted with some representation of the cherry blossom. With the unerring taste of the Japanese all the colouring is in harmony with the blossoms, no false note will clash or take away from the beauty of the surroundings. By the 1st of April all is in readiness for the visitors, who from that day onwards will not fail to arrive in a never-ending stream during the whole month. Even if there come days when the rain descends in pitiless torrents, it does not seem to damp their ardour; their clogs may be an inch or so higher; their kimonos will be girt tighter about their knees, to keep them from the mud; each one will carry a huge paper umbrella, black and red, deep blue or purple, or, commonest of all, the natural yellowish colour of the oiled paper, with the owner's name or the sign of the inn to which it may belong in large Katahana characters. Or should it be a late season and the cherry not be in flower so early, it makes no difference, still the people come, it is the time when it ought to be in flower, and such is the imagination in the minds of these curious people, that they will gaze for hours at a tree with scarcely more than a tinge of colour in the buds with as much pleasure as, if the tree were in all the glory of its full flower. On a holiday afternoon, when the weather is fine, every seat in the tea-houses is taken up by the pleasure parties, while in the open spaces the people spread mats brought with them for the purpose, and sit unfolding those neat little boxes and packets which contain their mysterious and wonderful food so unpalatable to our foreign ideas. Even the cakes and sugar-plums that accompany the cups of tea, unceasingly supplied by the tired little ne sans of the tea-houses, are in the shape of cherries impaled on wooden skewers, and eaten with relish by young and old alike. In no other country but Japan, where humanity is so closely associated with nature, and where the people mingle harmoniously with the background of flowers and trees, could one find such a scene — the entire population of a great city given up to the whole-hearted enjoyment of nature.  The Feast of the Cherry Blossoms At nightfall the lanterns are lighted, and flaring torches round the giant tree cast their lurid light upon the heavily laden branches, which might well belong to some forest tree bending under the weight of freshly fallen snow. Those who cannot leave their work during the day, come forth at night to swell the throng. The sounds of music and feasting, the beating of tom-toms, and the ceaseless dragging of ten thousand clogs mingle with the cries of the toy-seller whose stock of those wonderful paper butterflies, and of the miniature lanterns with the candles ready lit, has to be constantly replenished to supply his endless customers. Thousands of country people, wearied with their round of sight-seeing, spend the night on the grass, only to start again at daybreak on a fresh pilgrimage of innocent pleasure. The Emperor Kameyama in the twelfth century planted a number of cherry-trees from Yoshino at Arashiyama, a picturesque gorge where the river Katsura, celebrated for the beauty of its rapids, running through a narrow valley, becomes a wide and shallow river and is renamed the Oi gawa. Here it is said this Emperor built a pavilion, and, during the cherry month, the Court held high revel for many years. The pavilion has long since disappeared, perhaps swept away by one of the numerous floods which devastate these valleys: but the cherry-trees remain, and here, instead of the stately Court of ancient days, the modern Kyoto sight-seers hold their revels, for Arashiyama may be said to rank first among their favourite spring resorts. They gather in the tea-houses and flower-booths on the banks of the river, and spend their flower-viewing days by the running water and the clouds of white blossom, exclaiming possibly in the words of their poet, "Not second to Yoshino is Arashiyama, where the white spray of the torrent sprinkles the cherry blossom." Barge after barge, roofed over, with matted floor and decorated with innumerable lanterns to suggest a miniature tea-house, will take its load of visitors across the river, or they will spend some hours drifting idly down the stream, eating their midday meal or playing some childish game. Occasionally a flower-laden boat, which has successfully accomplished the passage of the rapids, will come into sight, and the sound of samisens, the saddest of all music, comes floating through the air. The habit of drinking saké while viewing the cherry blossom appears to have originated in the days of the Emperor Richiu, in the fifth century. While feasting with his courtiers in a pleasure-boat on a lake in one of the royal parks, some petals fell into his wine-cup, and drew the attention of the monarch to the hitherto despised blossom, and he exclaimed, "Without wine, who can properly enjoy the sight of the cherry blossoms?" — a sentiment which appears to have survived to this day. It was not, however, until the eighth century that the cherry blossom rose to the distinction of a national flower. The Emperor Shomu, while hunting on Mount Mikasa, in the province of Yamato, was so struck by the beauty of the blossoms, that he sent some branches, accompanied by some verses of his own writing, to his consort Komio Kogo. Afterwards, in order to satisfy the curiosity of the Court ladies, who had never seen this wonderful flower, he commanded a number of the trees to be planted round the Palace of Nara, whence arose the custom of planting them near all the royal palaces in the country. The province of Yamato is especially celebrated for its cherry groves, and justly so, as the little mountain village of Yoshino has given the name to the most famous of all the varieties, and has even been called the headquarters of the cherry blossom; and so profuse is the mass of blossom that the poets have compared it to mist or snow upon the hills. The little street of the village winds away up the spur of the hill, past many temples and shrines, until it becomes nothing but the rough stony path which ascends Mount Omine. Although the village stands high above the sea, its own especial kind of cherry is rather an early one; the blossoms are large and single, pale pink in colour; but its beauty is fleeting, and the visitor must go early in the "cherry month" to Yoshino, or he will be greeted by great showers of the falling petals being swirled away on the wind to join the light fleecy clouds on Mount Omine, or down to the mists which hang in the valley below, and nothing will be left but the remains of departed glories. During the few days, early in April, when the blossom is at its best, thousands of pilgrims visit the little village and occupy every available lodging; but the traveller who is not discouraged by the discomfort of primitive Japanese inns, or by the long tedious journey over the mountains from Nara, will find ample reward in the beauty of his surroundings. Mr. Parsons, in his Notes on Japan, thus described Yoshino: —

Everything in Yoshino is redolent of the cherry: the pink and white cakes brought in with the tea are in the shape of its blossoms, and a conventional form of it is painted on every lantern and printed on every scrap of paper in the place. The shops sell preserved cherry flowers for making tea, and visitors to the tea-houses and temples are given maps of the district — or, rather, broad sheets roughly printed in colours, not exactly a map or a picture — on which every cherry grove is depicted in pink. And all this is simply enthusiasm for its beauty and associations; for the trees bear no fruit worthy of the name. . . . I was reminded constantly of a sentence a friend had written in one of my books, "Take pains to encourage the beautiful, for the useful encourages itself." It is difficult for an outsider to determine how much of this is genuine enthusiasm and how much is custom or traditional estheticism, but it really matters little. That the popular idea of a holiday should be to wander about in the open air, visiting historic places, and gazing at the finest landscapes and the flowers in their due season, indicates a high level of true civilisation, and the custom, if it be only custom, proves the refinement of the people who originated it.  The Pink Cherry Tokyo and its neighbourhood can lay claim to some of the most beautiful spots for viewing the cherry blossoms. The banks of the river Sumida at Mukojima are lined for miles with an avenue of ancient trees bending almost to the water's edge with the weight of their double blossoms. This is the favourite resort of the Tokyo holiday-makers, and crowds of pedestrians, carrying their gourds of wine, inaugurate a veritable Bureiko (carnival) and fill the booths and the houses which are temporarily erected along the banks of the river. Those citizens who can afford the greater luxury of a barge or roofed pleasure-boat spend the evening more peacefully in floating upon the calm surface of the river, gazing at the blossoming trees, cheered by the singing of the geishas and the playing of the samisens. So great is the attraction of cherry blossoms seen by the light of the pale moon, that they have even been given the special name of Yozakura or night cherry flowers. To the foreigner wishing to enjoy the prospect of the cherry blossoms in peace, such boisterous feasting will seem out of harmony with the natural quiet beauty of the spot, and he will do well to turn his steps and to spend a few hours in undisturbed enjoyment of the more dignified setting of Uyeno Park, where the giant trees of single and drooping blossom stand out in splendid contrast to the pines and cryptomerias surrounding the tombs of the Shoguns. Ralph Adams Cram thus describes the scene: —

Here the cherry trees are huge and immemorial, gnarled and rugged, but clutching sunrise clouds caught by the covetous hands of black branches, and held dancing and fluttering against the misty blue of the sky. Here and there a weeping cherry holds down its prize of pink vapour, until it almost brushes the heads of those who pass; here and there the background of bronze cryptomeria is flecked with puffs of pink, as though now and then the captive clouds had burst from the holding of crabbed branches only to be caught in their escape toward the upper air and prisoned by the tenacious fingers of the cedar. At the end of the road the path blurs in odorous mist, and in a moment we are enveloped in the rosy clouds. As far as the eye can reach stretches the low-hung canopy of the thin petals; the trunks of the trees are small and gray, and one forgets them, or never thinks to associate them with the mist of pale vapour overhead, hung in the soft air, impalpable, evanescent, a gauzy cloud, lifted at dawn and poised breathless close over the earth. A little wind ripples above, and the air trembles with a snow of pink petals swerving and sliding down to the carpet of thin fallen blossoms, while darting children in scarlet and saffron and lavender crow and chatter, catching at the rosy flakes with brown fingers. The light here is pale and pearly as it filters through the sky of opal blossoms, and it transmutes the small dusky people into the semblance of butterflies and birds, now gathering into glimmering swarms of flickering colour, now darting off with shrieks of delight over the carpet of fallen petals. Here a slim girl with ivory skin has thrown off her ivory kimono, and clothed only in a clinging gown of vermilion crepe opening low on her bosom, barefooted, a great dancing butterfly of purple rice paper clinging to her black hair, is swaying rhythmically in an ecstatic dance, pausing now and then to flutter away like a red bird up the shadowy slope, until her flaming gown gleams among stone lanterns half lost in the gloom of great trees. Here a ring of shrieking children, wrinkled old women, and half-naked coolies are circling hand in hand in some absurd little game; and here, there, and everywhere whole families are clustered on red blankets, eating endless rice and drinking illimitable sake, while the tinkle of the samisen is in the air, and strange cool voices sing wistful songs in a haunting minor key. It is a kaleidoscope of flickering colour, a transformation scene of pearl and amber, opal and vermilion.

Koganai, a day's excursion from Tokyo, is another attractive spot in the cherry blossom season — an avenue of double cherry-trees stretching for two and a half miles along the river Tama. As the name suggests, tama meaning pearl, the water is clear, and the stream provides the people of Tokyo with their drinking water, which is brought to the city by means of an aqueduct. It is said that some ten thousand trees were originally brought from Yoshino, by command of the Shogun Yoshimune, and planted along the banks of the aqueduct, with the pretty idea that the purity of the blossoms would keep off impurities from the water-supply. Of this vast number of trees, even if they ever really existed, only a few hundreds remain to-day, but sufficient to keep up their old reputation and attract enough visitors for yet another merry and boisterous flower carnival; in fact, throughout the land, wherever there are cherry-trees, during the month of their glory there will be feasting. The blossom seems to act as a magnet to draw the people together, and often by the wayside I have seen just one solitary tree, in all the fulness of its beauty, made sufficient excuse for a miniature feast. Just a few lanterns will be hung in the tree, a few matted benches will be spread out, and an old Sand san will be waiting to greet any passing traveller with her cries of Irasshai — o kake nasai — Welcome — please sit down, — and the offer of the inevitable tea, tobacco-box, and hibachi. The Emperor Saga, as early as the ninth century, inaugurated the Imperial garden parties to view the cherry blossom, which still take place annually at the old summer palace of the Shoguns, Shiba Rikyu. The gatherings were attended by the writers and poets of the day, who composed odes on the blossoms. Although robbed of many picturesque features by the lamentable custom of wearing foreign dress at Court, these functions are still of great interest to the foreigner, as affording him the only available opportunity of visiting any of the Imperial gardens of the capital. In spite of the fact that the beauties of Tokyo are fast disappearing — her moats bordered by splendid pines are  Cherry-tree at Kyomidzu almost things of the past; broad streets with tramways, brick and stone houses, are fast replacing the narrow streets and little wooden houses of old Yedo; the Yashiki or Daimios' houses and gardens are gone, replaced by foreign houses, — Tokyo still retains her cherry-trees. No modern reformer has ever dared to sweep away her avenues of sakura, for to the Japanese the cherry is something more than an ordinary flower; it is difficult, if not impossible, for our Western minds to enter into their conception of it. To them the soul of the sakura, or cherry blossom, is the soul of Bushido (Chivalry), and the heart of Bushido is the heart of Japan. One of their songs says —

Hito wa bushi. (Among flowers the cherry, Among men the samurai.)

The precepts of Chivalry were started first as the glory of the élite, but grew in time to be the aspiration of the whole nation, and they found their ideal in the sakura. The phrase, Chitte koso sakura nari, meaning "It's a cherry blossom, it falls when it must," was taught in the old feudal days — how to die from loyalty as the cherry blossom, — the ethic of Death was the highest. So to this day their ethics remain the same, and Tokyo retains her cherry-trees, which in spring transform the town into a garden of blossom. The poet Bashio sang in his hokku poem —

Sane wa Uyeno ka Asakusa ka. (A cloud of flowers Is it the bell from Uyeno Or from Asakusa?)

It is true that wherever the clouds of blossom are low they will shut out the prospect in Tokyo, and one is unable to tell whether the bell which sounds from far away is that of Asakusa or Uyeno. The number of different kinds of cherry-trees seems unlimited; Japanese authorities quote one hundred distinct varieties. The first, and almost the most beautiful, to flower, is the Ito sakura or drooping cherry, with pendent branches like a weeping willow, and so-called from ito, meaning thread. These trees attain to a great size and make magnificent specimens. Almost at the same time bloom the Higan sakura — equinox cherries — with white single flowers or pale pink. Such are most of the trees at Uyeno, of majestic size, planted, it is said, by one of the Tokugawa Regents in imitation of the hills at Yoshino, though Asakusa yama, a hill in the suburbs of Tokyo, is more often spoken of as the new Yoshino. The Ukon sakura is very lovely, with its clusters of pale greenish-yellow double blossoms, but is rather scarce, and a variety known as Yaye hotoye has single and double blossoms on one tree, — yaye meaning single and hotoye double. The Yoshino cherry I have already described; Hi sakura has double blossoms, deep crimson in bud, and bright pink when open. There seems to be a never-ending list of these lovely trees, in bewildering variety — early and late kinds, single, semi-double and double, large and small, from pure white through every shade of blush pink to light crimson, and the one beautiful pale yellow blossom, its outer petals just flushed with pink, suggesting the colouring of a tea-rose rather than a cherry blossom. The double varieties of course bear no fruit, but even the single "equinox cherries" bear none, so the Japanese are satisfied with their splendid blossom and do not worry about the poor insipid little fruit, which is all a cherry represents to them; but they will salt the leaves and drink cherry-flavoured tea under the pink canopy of flowers during the time of the cherry blossoms, when, in the gladness of spring, all the world is making merry. |