|

IV. DAY

TRIPS FROM BOSTON

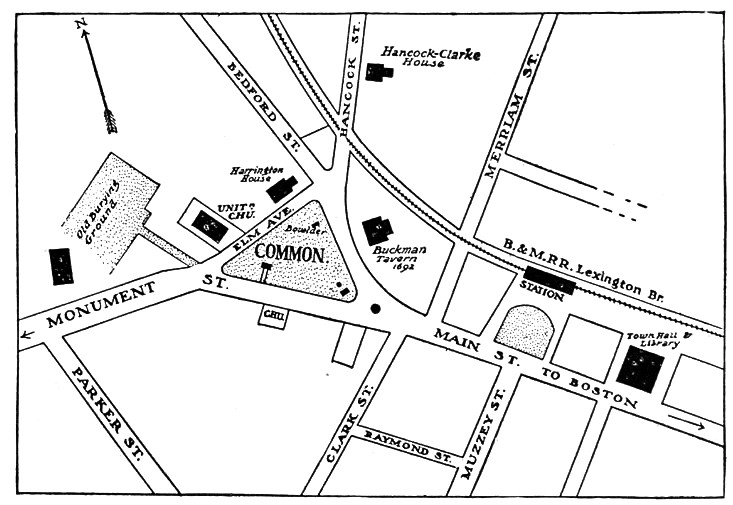

LEXINGTON

AND CONCORD

Lexington

is reached from Boston by electric car via Arlington, or by train,

Boston & Maine Railroad, North Station. Concord is also

reached by both electric and steam cars. To include both places in a

single trip there is a choice of routes: one wholly by trolley car,

another partly by trolley and partly by steam car (from Lexington to

Concord), a third wholly by train. The route wholly by electrics is

by an Arlington Heights car, passing along Massachusetts Avenue

through Cambridge and Arlington, to the Lexington town line; thence

by a Boston and Lexington electric car, through East Lexington to

Lexington Center, by the historic green; thence to Concord by way of

Bedford, finishing in the main square of the town. To reach Concord

directly from Boston the usual and by far the quickest way is to take

the steam railroad. There are two routes, — one by the Fitchburg

Division of the Boston & Maine, the other by the Southern

Division, the latter being the line which comes through Lexington.

The

trolley-car route to Lexington passes numerous historic points in

Arlington (the early Menotomy, later West Cambridge), all

associated with the affair of the 19th of April, 1775. Before the

town line is reached the visitor must needs be on the lookout for

tablets. In North Cambridge (Cambridge station on the

near-by

railroad) is the first one. This stands just above the church beyond

“Porter’s,” the old hotel, a relic of past days. It marks a

point where four Americans were killed by British soldiers on

the retreat. Two miles and more beyond, after a brick car house is

passed and the railroad crossed, the next tab let may be seen, on the

right side of the road. This marks the site of the Black Horse

Tavern, where three members of the Committee of Safety of 1775 —

Colonel Azor Orne, Colonel Jeremiah Lee, and Elbridge Gerry of

Marblehead — were spending the night of the 18th of April, and

barely escaped capture by the British soldiers on the march out to

Lexington and Concord.

Nearing

the town center, the Arlington House is marked, “Here stood

Cooper’s Tavern, in which Jabez Wyman and Jason Winship

were

killed by the British, April 19, 1775.” A little way beyond this

tavern, at the right, is Mystic Street, down which, a hundred yards

from the avenue, is a tablet inscribed with this marvelous

tale: “Near this spot Samuel Whittemore, then eighty years old,

killed three British soldiers April 19, 1775. He was shot,

bayonetted, beaten, and left for dead, but recovered and lived to be

ninety-eight years of age.” At the junction of the avenue and

Pleasant Street, in front of the church green, a tablet records that

“at this spot on April ,9th, 1775, the old men of Menotomy captured

a convoy of English soldiers with supplies, on its way to join the

British at Lexington.” Behind the church on Pleasant Street is the

old burying ground where a number who fell in the fight during the

British retreat were buried. Farther down Pleasant Street, on the

borders of fair Spy Pond, is the home of John T. Trowbridge,

author and poet.. On the avenue again, above the church green, is the

fine Robbins Memorial Library, and a little beyond this, near

the corner of Jason Street, another tablet appears, identifying the

“site of the house of Jason Russell, where he and eleven others

were captured, disarmed and killed by the retreating British.”

Farther along on the plain near ing Arlington Heights are two or

three old houses which suffered damage in the fight. At the top of

the incline the “Foot of the Rocks,” as this point was

called at the time of the Revolution, is reached. To the left a road

leads up to “the Heights,” from which a beautiful view is to be

had.

The

car stables close to the Lexington line are only a little way beyond.

Here the change is made to the Lexington car a few steps above.

East

Lexington, or the East Village as it used to be called, is now a

tranquil hamlet, with an old-fashioned store or two, some

comfortable, looking houses along the main avenue, a few memorials of

the British invasion, and a little church in which Emerson

occasionally preached (the octagonal structure on the right side of

the avenue, known as the Follen Church, from Charles Follen,

the German scholar, its minister, who was lost in the burning of the

steamer Lexington on Long Island Sound in 1840). At the

junction of the avenue and Pleasant Street is a tablet set up

beside a drinking fount, which marks the point where the first armed

man of the Revolution was taken, — only to rearm him self and fight

later on Lexington Green. He was Benjamin Wellington, a minuteman. A

short distance beyond is a plain white house, on the right side, upon

which is a tablet identifying it as the “home of Jonathan

Harrington, the last survivor of the Battle of Lexington.” This,

how ever, was not the place where Jonathan lived at the time of the

fight. He was a boy then (a fifer to the minutemen) and lived with

his father, another Jonathan Harrington, whose house also is

standing, a little farther on, at the corner of Maple Street. In the

sidewalk in front of the latter house is one of the largest elms in

New England. One day in 1753 the elder Jonathan drove an ox team to

Salem, and on the way back he pulled up an elm shoot to brush the

flies off the oxen. When he got home he set it out, and this great

tree has grown from it.

Lexington.

After passing the rural station of Munroe’s, on the rail road, the

first object of interest, and a worthy one, is Munroe’s Tavern,

standing on an elm-shaded knoll at the left of the avenue. On its

face is a tablet thus inscribed: “Earl Percy’s headquarters and

hospital, April 19, 1775. The Munroe Tavern built 1695.” Percy

occupied the room on the left of the entrance door, and this was made

the temporary hospital. The room on the right was the taproom, where

the soldiers were freely supplied with liquor.

Lexington

When

the retreat began some of the soldiers discharged their guns, killing

John Raymond, who had served them and who was trying to escape

through a back door. A bullet hole made by one of the British musket

balls is still seen in the ceiling of this room. The depart ing

soldiers also started a fire in the tavern, but it was put out. In

the southeast part of the second story was the tavern dining room,

and here Washington dined in November, 1789, when on his last journey

through New England. This house was much larger then, with spreading

outbuildings. Abandoned as a tavern years ago, it has been preserved

as a memorial of the Revolution.

As

the town center is approached historic sites multiply. The hill on

the left is marked as the point where one of the British fieldpieces

was planted to command the village and its approaches. Near it, we

are informed by the same tablet, “several buildings were

buried.” A little way beyond Bloomfield Street, at the left, is

about the point where Percy met Smith’s retreating force, and at

the right, in front of the High School, a granite cannon marks the

spot where he planted a field piece to cover the retreat.

Arrived

at Lexington Green, — the Common where the “battle”

occurred, — the visitor will find every point of importance

designated by a monument or tablet. Thus at the lower end is the

stone pulpit marking the site of the first three meetinghouses, a

“spot identified with the town’s history for one hundred and

fifty years.” Near by is a bronze statue of a yeoman with gun in

hand standing on a heap of rocks. Where the minutemen were lined up

is indicated by a bowlder inscribed with the words of Captain

Parker: “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if

they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” On the west side of

the ground is the old stone monument, now in a beautiful

mantle of ivy, which the State erected in 1799, and for which the

patriot minister of Lexington, Jonas Clarke, wrote the oratorical

inscription. In a stone vault back of it are deposited the remains of

those who fell in the engagement, which were removed to this place

from their common grave in the village burying ground. With the

modern houses about the green are three which were standing at the

time of the battle. On the north side is a house in an old garden

which was the Buckman Tavern, “a rendezvous of the

minutemen, a mark for British bullets,” as the tablet on its face

states. On the south side a plain white house bears the legend, “A

witness of the battle.” On the west side, at the corner of Bedford

Street, is a house in which lived Jonathan Harrington, who, “wounded

on the Common” in the engagement, “dragged himself to the door

and died at his wife’s feet.” A few steps from the Unitarian

Church, on this side, is a lane with a bowlder at its corner marked

“Ye Old Burying, Ground 169o.” Among the many quaintly inscribed

gravestones here are the tombs of the ministers John Hancock,

grandfather of Governor John Hancock, and Jonas Clarke, and monuments

to Captain Parker of the minutemen and Governor William Eustis, who

was a student with General Joseph Warren and served as a surgeon at

Bunker Hill and through the war. He was governor of the State in

1823-1825.

On

Hancock Street is the historic Hancock-Clarke house (moved

from its original site on the opposite side of the way), the home of

the ministers, first Hancock and then Clarke. Here John Hancock

and Samuel Adams were stopping the night before the battle,

and were roused at midnight from their sleep by Paul Revere,

when they were taken by their guard to Captain James Reed’s in

Burlington. The venerable house is now a museum of Revolutionary

relics. In the Town Hall, below the green, are the Memorial Hall and

Carey Public Library, in which is a larger museum of relics, with

numerous portraits, old prints, and Major Pitcairn’s pistols,

captured during the retreat. Here are statues of The Minuteman of

‘75; The Union Soldier; John Hancock, by Thomas R. Gould; and

Samuel Adams, by Martin Milmore. In the public hall above is a fine

painting of the Battle of Lexington by Henry Sandham.

Waltham

Street, opening directly opposite the Town Hall, leads toward the

birthplace of Theodore Parker, in Spring Street, about

two

miles distant.

Concord

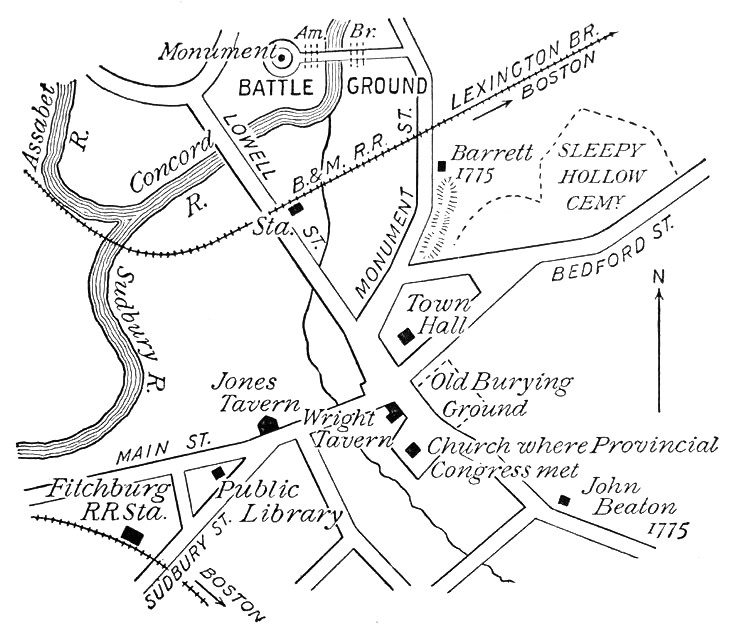

Concord.

The heart of the town is the square in the center, where the most

conspicuous object is the

Unitarian

Church, destroyed by fire in 1900, and wisely rebuilt on the old

simple and dignified lines. This was the site of a still older

meeting house where the Provincial Congress sat. Next to it is the

Wright

Tavern, dating from 1747. Here Major Pitcairn drank his toddy on

the day of the fight.

Taking

the Lexington road from the square we pass, first, the

Concord

Antiquarian Society’s house, full of relics and old furniture,

and, a little farther, on a road diverging to the right,

|

The

Emerson house, where Ralph Waldo Emerson lived the greater part

of his life and where he died. His study is preserved as he left it.

The house was long after occupied by his daughter, Miss Ellen

Emerson. Returning to Lexington Street and proceeding about a quarter

of a mile, we come to

The

School of Philosophy and Alcott house. The unpainted,

chapel-like building was the home of the school, and the house near

it was the “Orchard House,” in which the Alcott family lived for

twenty years. Here Louisa M. Alcott wrote “Little Women,” which

turned the tide in the family’s fortunes. Just beyond, under the

hill, is

The

Wayside, also occupied at one time by the Alcotts, but better

known as the home of Hawthorne after the return from Europe. Here the

family were living at the time of Hawthorne’s sudden death in New

Hampshire. “Hawthorne’s Walk “is on the crest of the ridge that

rises abruptly behind he house. Returning to the square, we ascend,

on the right, the old

|

The Alcott House |

Hillside

Burying Ground. Here are historic graves, including those of

Emerson’s grandfather and Major John Buttrick, who led the fight at

the Old North Bridge; and some unique epitaphs, especially that of

John Jack, the slave. The church near this burying ground is now a

Catholic church, and turning the corner of the street on which it

stands, we soon come to

|

Sleepy

Hollow Cemetery. Here, on a high ridge beyond the beautiful

hollow which gives the cemetery its name, are, in proximity, the

graves of Hawthorne, of Emerson, of Thoreau, of Louisa M. Alcott and

her father. Near the foot of this slope should not be over, looked

the Hoar family lot and the beautiful epitaphs placed by the late

Judge Hoar upon the monuments to his father, Samuel Hoar, and to his

brother, Edward Hoar. The exquisitely appropriate inscription on the

Soldiers’ Monument in the square was also written by Judge Hoar.

Returning once more to the square, and proceeding thence on Monument

Street for about half or three quarters of a mile,

The

Old Manse, where Emerson wrote “Nature,” and Hawthorne lived

for a time, is seen on the left, standing back from the road. The

study of both Emerson and Hawthorne was a small room at the back of

the second floor. This house was built ten years before the battle at

the bridge close by, and was for many generations the home of the

minister of the village. Nearly opposite is the house of the late

Judge Keyes, dating from before the Revolution, and in the ell of

which may still be seen the hole through which passed a musket ball

fired at some patriot who was standing in the doorway at the time of

the fight.

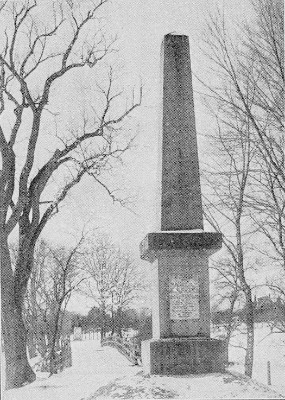

The

Battle Ground. The wooded lane just beyond the Old Manse leads to

the scene of the battle at the Old North Bridge, the story of which

is told by the inscriptions on the monuments there. Most pathetic is

the simple inscription which marks the graves of unknown British

soldiers killed on the spot. French’s bronze Minuteman fitly stands

on the opposite side of the river, at about the point where the

Americans made their attack.

|

Battle Monument |

House

of the First Minister. If on our way back we turn to the right

after crossing the railroad tracks, and then to the left, we shall

pass the site of the house in which Peter Bulkeley, the first Concord

minister, lived, — he who made the bargain with the Indians for the

land of Con cord, which secured to the colonists its “peaceful

possession.” This is on Lowell Street, and a few steps farther and

facing the square, our starting point, is a low wooden block, a part

of which was one of the storehouses sacked by the British.

Continuing

through the square and turning to the right, the first house beyond

the very pretty bank building is one a part of which is said to have

been the original blockhouse built by the first settlers as a defense

against the Indians. Beyond, on the left, at the junction of the two

roads, is the

Concord

Public Library. Here are some interesting busts and pictures, and

a collection — astonishingly large — of books written by

residents of Concord.

Homes

of the Hoar Family. Continuing on the main street, the fourth

house from the blockhouse was the home of Samuel Hoar, the first of

the name. Here were born his eminent sons, the late Judge Hoar and

Senator Hoar. The next house was the home of the late Samuel Hoar,

the eldest son of Judge Hoar; and the next beyond that is the home of

the widow of Sherman Hoar, Judge Hoar’s youngest son. On the left,

near the corner of Thoreau Street and secluded by a hedge of trees,

is the

Thoreau

House. Here Thoreau lived during the last twelve years of his

life, and here he died of consumption. The Alcott family also lived

in this house for several years. The site of Thoreau’s hut by

Walden Pond is marked by a cairn made by visitors. Still continuing

on the main street and bearing to the right, we find, just beyond the

little stone Episcopal church which stands on the left,

The

Home of Frank B. Sanborn. Here, in what is perhaps the prettiest

house in Concord, and close to the river, lives Frank Sanborn, the

last of the men who gave Concord a world-wide reputation, and famous

as an antislavery man, as schoolmaster, lecturer, and author. A mile

or more beyond the Sanborn house is

The

Concord Reformatory. This institution, intended for younger and

the less hardened criminals, is a large one, and is believed to be a

model of its kind.

Concord

Schools. Concord has always been remarkable for its schools; and

besides its public schools it contains an Episcopal boarding school,

with grounds sloping to the river, not far from the Sanborn house,

and also a Unitarian boarding school, situated on the road to Lowell,

about three miles beyond the village.

Home

of Edward W. Emerson. On the same road, a mile or so beyond the

village, is the home of Emerson’s only son, Dr. Edward W. Emerson,

a physician and artist, and the author of that most valuable and

interesting book, “Emerson in Concord.”

THE

NORTH SHORE

Lynn

(about 12 miles distant from Boston) can be reached in twenty minutes

by steam railroad (Boston & Maine, Eastern Division, from the

North Station) or by the Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn Railroad, a

longer route but running closer to the sea, which begins with a short

trip in a ferryboat, taken at Rowe’s Wharf, Atlantic Avenue (a

station of the elevated railway close by). If time can be spared, one

may journey pleasantly to Lynn in Boston and Northern electric cars,

taken in the Subway at the Scollay Square station, and running

through the Charlestown District (past the Navy Yard), Chelsea,

Revere, and thence straight across the broad Saugus marshes with

their numerous inlets, and with the ocean in sight on the extreme

right. We reach first

West

Lynn. The works of the General Electric Company and numerous shoe

factories are here. A mile or so beyond is Lynn proper, a great shoe

city. At Central Square electric cars may be taken for trips in

various directions, especially to the Lynn Woods, the beautiful

reservation of about two thousand acres. From Central Square, also,

“barges” (a kind of long-drawn bus) run to the aristocratic

summer resort of

Nahant

(“cold roast Boston”), the oldest of eastern summer resorts,

occupying a rocky promontory. On the extreme point is the summer home

of Henry Cabot Lodge. There is also good sea bathing here, cold as

ice water. To the northeast is Egg Rock with its lighthouse, showing

a fixed red light. Returning to Lynn, an electric may be taken, if

one desires, to

Saugus.

Here are the Boardman houses, so called, the homes of minutemen in

1776, and “Appleton’s pulpit,” a huge rock, from which in

September, 1687, Major Samuel Appleton of Ipswich harangued the

people in favor of resistance to Andros. Here also is the site of the

first iron mine and foundry in the Colony.

Returning

again to Lynn, we may take an electric car for Salem via. Swampscott

and Marblehead, — a pleasant route passing many summer homes and

traversing the Lynn Shore Reservation of the Metropolitan Parks

System, which at its northern end joins King’s Beach in Swampscott.

Passing Beach Bluff and Clifton Heights, we come to

Marblehead,

the quaint, irregular town with crooked streets full of old-time

suggestions. Barges or a steam ferry may be taken here to Marblehead

Neck, the site of a summer hotel and of the clubhouses of the Eastern

and Corinthian Yacht Clubs. At the north end of the town is Fort

Sewall, and various islands are in sight, notably “Misery”

island, which is devoted by a club to sports and merriment. Features

within easy walks are the old Town Hall with memories of the

Revolution; the birthplace of Elbridge Gerry; remnant of the historic

Jeremiah Lee mansion; the home and the tomb of General John Glover,

whose statue is in Boston (see page 78); St. Michael’s, the oldest

Episcopal church now standing in New England; the “Old Floyd

Ireson” house; birthplace of “Moll Pitcher,” the “fortune

teller of Lynn”; and the well of the “Fountain Inn,” the old

tavern where began the romance of Agnes Surriage. From Marblehead we

may go by electric car or by steam railroad — or one might have

gone directly from Boston by the Boston & Maine (North Station) —

to

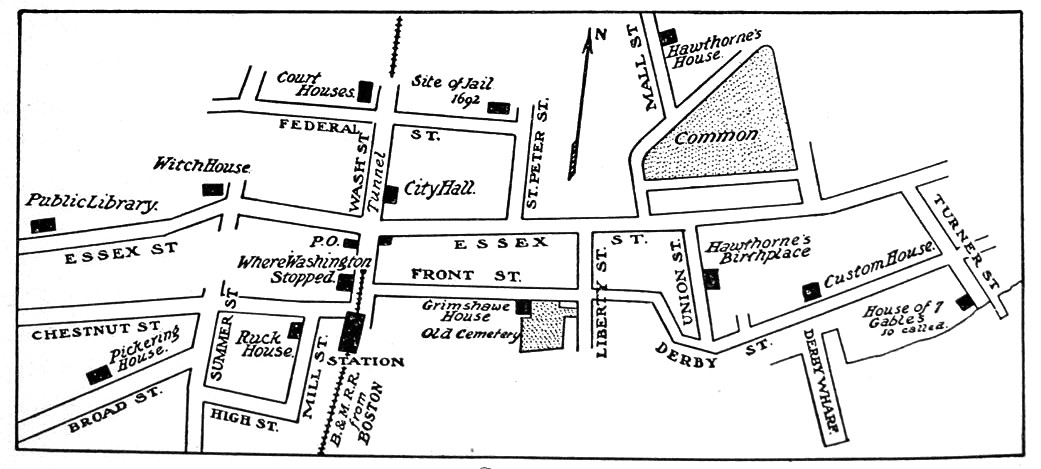

Salem

Salem,

once the chief port of New England. Here are many stately, reposeful

old houses: the Custom House, in which Hawthorne was employed; the

County Jail and Court House, in which many relics of the witchcraft

persecution are preserved; Gallows Hill, where the condemned were

hung; the Roger Williams house; the house on Federal Street in which

Lafayette was entertained in 1784 and Washington in 1789; Hawthorne’s

birthplace on Union Street, and various Hawthorne homes and

landmarks; and the Pickering mansion, built in 1649. Here also are

the Essex Institute and the Peabody Academy of Science, with their

interesting collections of documents, relics, and curiosities, many

of them redolent of the sea and foreign commerce.

Near-by

towns are

Peabody,

named for George Peabody, the London-American banker, with the

Peabody Institute, containing, besides many relics, a portrait of

Queen Victoria, given by her to Mr. Peabody; and

Danvers,

the home of General Israel Putnam, and at one time of Whittier. Here

stands the fine old Hooper or Collins house, one of the best of

Provincial mansions remaining, which General Gage used as his

headquarters in the summer of 1774; and not far away is the Colonial

farmhouse once occupied by Rebecca Nourse, the good house wife and

kind neighbor who was executed for witchcraft.

From

Salem electric cars run through Beverly to the tip end of Cape Ann;

but from Beverly they take an inland course through the towns of

Wenham, Hamilton, Essex, and West Gloucester, whereas the Gloucester

branch of the steam railroad diverges to the east at Beverly and runs

along the coast.

Beverly,

settled in 1628, is now a shoe town in one part and a summer resort

in the other parts. There are many wooded walks and drives here, and

through Pride’s Crossing, Beverly Farms, West Manchester, and

Manchester-by-the-Sea, noted for its “singing beach,” which gives

forth a musical note as one walks over it. Here also is the Masconomo

House, a famous summer hotel and the scene of open-air drama. Beyond

are Magnolia and

Gloucester,

the port from which the hardy fishermen sail to “The Banks” for

cod and haddock, and to which many of them never return. Kipling’s

“Captains Courageous” is the best guide book for Gloucester. At

the extreme tip of Cape Ann is

Rockport,

famous for its granite quarries, for its breakwater, built by the

Federal government, and for its rocky scenery, much haunted by

artists. The Isles of Shoals lie off the shore, and also Thatcher’s

Island, with its twin lights.

Salem

Itinerary. A day might well be devoted to Salem alone. The

following itinerary, arranged for the visitor who has only an hour or

two for its exploration, embraces the more important or most

interesting places and sites.

The

start is made from Town House Square (Washington Street at the

crossing of Essex Street), a little way above the railroad station.

On Washington Street, between the station and the square, on the west

side of the railroad tunnel, is seen the

Joshua

Ward House (No. 148), in which Washington passed a night when in

Salem on his tour of New England in the autumn of 1789. He occupied

the northeast chamber of the second story. This house is on the site

of the dwelling of the high sheriff, George Corwin, the

executioner of the witchcraft victims in 1692.

From

Town House Square turn into Essex Street east. The Unitarian Church

on the southeast corner occupies the site of the

First

Meetinghouse, built prior to 1635 for the first church in Salem,

formed in 1629. The present is the fourth in succession on this spot.

The second one was the place of the examinations of the unhappy

accused “witches” before the deputy governor and councilors from

Boston in April, 1692. Beside the third one, “three rods west” of

it, facing Essex Street, stood the

Town

House in which in 1774 met the last General Assembly of the

Province of Massachusetts Bay and the first Provincial Congress. A

short distance up Essex Street, at No. 101, is the

Peabody

Academy of Science (founded upon an endowment by George Peabody,

the American banker in London), in the East India Marine Building.

This contains the natural history and ethnological collections of the

Essex Institute, and the nautical museum of the East India Marine

Society (dating from 1799), with large additions, so arranged as to

be educational rather than merely entertaining. On the opposite side

of the street, at No. 134, is

Plummer

Hall, the house of the Salem Athenæum (proprietary

library, 24,000 volumes). This occupies the site of the house in

which William H. Prescott, the historian, was born, and in which

earlier lived Nathan Read, who invented and successfully sailed a

paddle-wheel steamboat in 1789, some years before Fulton. In Colony

days the Downing-Bradstreet house was here (the homestead lot

being covered by this building and its neighbor, the Cadet

Armory), first the home of the Puritan Emanuel Downing, whose son

George Downing gave his name to Downing Street in London, and

afterward that of Simon Bradstreet, the last colonial governor. Next

above Plummer Hall is the

Essex

Institute (No. 132), which comprises the Institute museum of

historical objects, manuscripts, documents, and portraits, many and

rare, the largest and most notable collection of its kind in the

country; and the library, containing about 85,000 volumes, 302,000

pamphlets, and 700 volumes of manuscript. The visitor upon entering

the Institute should procure a copy of its guide, which gives the

details of the interesting exhibit here.

From

Essex Street on the south side, just above these institutions, turn

into Union Street, which leads to the

|

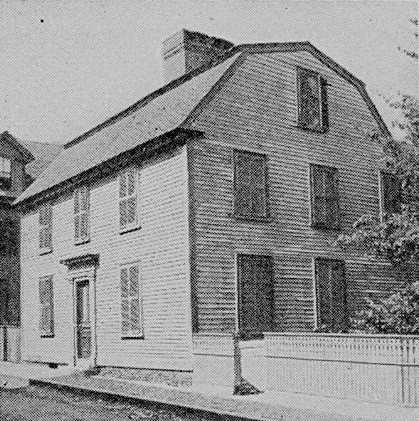

Birthplace

of Hawthorne, in the ancient gambrel-roofed house, No. 27. This

house dates from before 1692, and belonged to Hawthorne’s

grandfather, Daniel Hathorne (the romancer changed the spelling of

the name) after 1772. Hawthorne was born (1804) in the northwest

chamber. Back of this house, facing on Herbert Street, is the

Herbert

Street Hawthorne House (now

a tenement

house, Nos. 10 1/2 and 12), formerly owned by Hawthorne’s maternal

grandfather, Manning, in which much of the author’s boyhood was

passed, and where he afterward lived and wrote at intervals during

his manhood. His “lonely chamber” was the northwest room of

the third story.

From

Derby Street, which Union Street crosses, pass to Charter Street

northward, in which is the

Charter

Street Burying Ground, “Old Burying Point,” dating from 1637,

fancifully sketched by Hawthorne. Here are graves or tombs of

Governor Simon Bradstreet; the witchcraft judge Hathorne and other

ancestors of Hawthorne; the two chief justices Benjamin Lynde, father

and son; Nathaniel Mather, younger brother of Cotton Mather of

Boston, precociously learned and pious, who died “an aged man at

nineteen years”; Richard More, a boy passenger on the Mayflower;

and “Dr. John Swinnerton, physician,” whose name

Hawthorne

utilized in two of his romances. Adjoining the burying ground is the

|

Birthplace of Hawthorne |

“Dr.

Grimshawe” House (53 Charter Street) of “ Dr. Grimshawe’s

Secret” and “The Dolliver Romance,” — the home of Dr.

Nathaniel Peabody at the time of Hawthorne’s courtship of Sophia

Amelia Peabody, who became his wife. “Dr. Grimshawe” House (53

Charter Street) of “Dr. Grimshawe’s Secret” and “The Dolliver

Romance,” — the home of Dr. Nathaniel Peabody at the time of

Hawthorne’s courtship of Sophia Amelia Peabody, who became his

wife.

On

Derby Street, a short distance eastward, is the

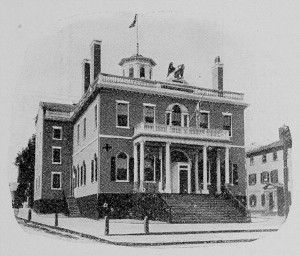

Salem Custom House

The + marks the the

office occupied by

Hawthorne |

Salem

Custom House. The office which Hawthorne occupied as surveyor

of the port in 1846-1849 was the corner room of the first floor, at

the left of the entrance. The stencil, “N. Hawthorne,” with which

he marked inspected goods, is preserved here as a memento; the desk

upon which he wrote is in the Essex Institute. The room in which he

fancied the discovery of the scarlet letter is on the second floor of

the easterly side of the building, in the rear of the collector’s

office. In Hawthorne’s time this was an unused room, with boxes and

barrels of old papers.

Three

or four streets east of the Custom House is Turner Street, by which

return should be made to Essex Street. On Turner Street the old house

No. 54 is marked the

House

of the Seven Gables. This is not correct, for Hawthorne, upon his

own statement, took no particular house for his model in the romance

of this name. The house is interesting, however, as one which

Hawthorne much frequented, it then being the home of the

Ingersoll family, his relatives. It may have suggested the title of

the romance. Here the “Tales of Grandfather’s Chair”

originated.

|

From

Turner Street cross Essex Street to Washington Square, with its

stately houses of early nineteenth-century build, bordering the fine

Common. On the north side, at the corner of Winter Street, is the

Story

House, in which lived Judge Joseph Story, and where his son,

William W. Story, the poet and sculptor, was born.

On Mall Street, the second street from this side, the house No. 14

was

Hawthorne’s

Mall Street House, where “The Scarlet Letter” was written.

The study here was the front room in the third story.

From

the west side of the square take Brown Street to St. Peter’s

Street, thence pass to Federal Street, and so to Washington Street

again by Town House Square. On Howard Street, north from Brown

Street, is the Prescott Schoolhouse, said to be near the site of the

place where Giles Corey, the last victim of the witchcraft frenzy,

was pressed to death. On Federal Street is the site of the

Witchcraft

Jail of 1692, covered by the house (No. 2) of the historical

scholar, Abner C. Goodell. In this jail the persons accused of witch

craft were confined, and from it the condemned were taken to the

place of execution. Some of the timbers of the old jail are in the

present house.

On

Washington Street, just about where Federal Street enters, is the

site of

Governor

Endicott’s “faire house.” At the southern corner of

Washington and Church streets stood the

Bishop

House, where in 1692 lived Edward and Bridget Bishop, the latter

the first witchcraft victim to be hanged. About opposite, on the west

side of Washington Street, near Lynde Street, was the

House

of Nicholas Noyes, minister of the first church at the time of

the witchcraft delusion, and a firm believer in witchcraft. In the

middle of the street here stood the

Court

House of 1692, where the witchcraft trials were held. In the

present Court House, at the end of Washington Street, facing Federal

Street, are

Witchcraft

Documents and Relics, in the custody of the clerk of the courts.

Among these are the manuscript records of the testimony taken at the

trials, the death warrant of Bridget Bishop, with Sheriff Corwin’s

return thereon, recording that he had “caused her to be hanged by

the neck till she was dead and buried,” the last words being

crossed with a pen, apparently by the careful sheriff on second

thought; and some of the “witch-pins” which were produced in

court as among the instruments of torture used by the accused.

Through Federal Street west and North Street north is reached the

North

Bridge, in place of the bridge of Revolutionary days, where the

“first armed resistance to the royal authority was made” on a

Sunday in February, 1775, nearly two months before the affair at

Lexington and Concord, when the advance of the British force, led by

Lieutenant Colonel Leslie, to seize munitions of war, was arrested by

the people of Salem. A spirited painting, “The Repulse of Leslie,”

is in the Essex Institute.

Return

through North Street to Essex Street west. On the corner of North

Street (310 Essex Street) is the

Witch

House, so called persistently without warrant beyond the

tradition that some of the preliminary examinations of accused

persons were held here, it being at the time of the delusion the

dwelling of Judge Jonathan Corwin of the court. It is said to have

been earlier the home of Roger Williams (in 1635-1636). It is the

oldest house now standing in Salem.

Through

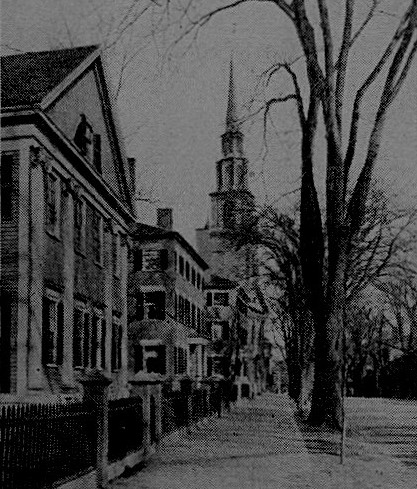

Summer Street from Essex pass to Chestnut Street, lined with great

elms and bordered by many fine old-time mansions. At No. 18 was

Hawthorne’s

Chestnut Street House, which he occupied less than two years at

the beginning of the surveyorship period. Little literary work

appears to have been done here. At an earlier period John Pickering,

the Greek lexicographer, lived in this house. On Broad Street, the

next street south, at No. 18, is the many-gabled

Pickering

House, dating back to 166o, the birthplace of Timothy Pickering,

the distinguished soldier and statesman of the Revolution and member

of Washington’s cabinet. Opposite, at the head of Broad Street, is

a succession of school buildings, —

The

Latin and High Schools, the former of which is one of the oldest

in the country. Behind these buildings is the

Chestnut Street, Salem |

Broad

Street Burying Ground, second in age to the Charter Street

Burying Ground, having been laid out in 1655. Here are the tombs of

the Pickerings, of Corwin, the witch craft sheriff, and of General

Frederick W. Lander.

Return

to Essex Street, and after a call at the Public Library (No. 370), on

the corner of Monroe Street, and a glance at the fine old-time

mansions of the neighborhood, — notably the Cabot house, dating

from 1748, for a third of a century the home of William C.

Endicott, justice of the State Supreme Court and member of

President Cleve land’s cabinet, — take a car for

Gallows

Hill, where the nineteen victims of witchcraft were hanged. It is

on Boston Street (the old Boston Road), approached from Hanson

Street, where the conductor should be signaled to stop.

Returned

to Town House Square, the visitor may, if he have time, spend a few

minutes profitably in the City Hall in looking over the unusual

collection of portraits here. They include a Washington painted by

Jane Stuart, a copy of a half-length portrait by her father, Gilbert

Stuart; a portrait of President Andrew Jackson by Major R. E. W.

Earle of his military family in 1833; and portraits of Endicott.

South of the railroad station is a nest of old buildings in old

streets, among them the Ruck house, 8 Mill Street, dating from

before 1651, interesting as the sometime home of Richard Cranch,

where John Adams frequently visited (Adams and Cranch married

sisters), and at a later time occupied by John Singleton Copley, the

Boston painter, when here painting the portraits of Salem worthies.

|

THE

SOUTH SHORE

The

pleasant places along the South Shore between Quincy and Plymouth are

brought into connection with Boston and with each other by

electric-car systems, while the steam railroad traverses the country

closest to the shore. The most direct electric-car route from Boston

to Plymouth is through Quincy, Braintree, South Braintree, Holbrook,

Brockton, Whitman, Hanson, Pembroke, the Plymouth Woods, West

Duxbury, and Kingston. For this route the Neponset car should be

taken at the Dudley Street terminal of the Elevated. The trunk line

continues through Quincy to Brockton, where change is made to the

Plymouth line. Other lines between Quincy and Brockton pass through

Quincy Point, across Weymouth Fore River, through Weymouth, cross ing

Weymouth Back River, Hingham, the Old Colony Woods, Nantasket,

Hingham Center, Rockland, and Whitman, making connection at the

latter place with the Plymouth line.

The

pleasantest steam-railroad journey is by the South Shore route (New

York, New Haven & Hartford system, South Station), passing

through Quincy, Braintree, Weymouth, Hingham, Cohasset, Scituate,

Marshfield, Duxbury, and Kingston, to Plymouth. The more direct route

is by the main line through Braintree, South Weymouth, Abington,

Whitman, Hanson, Halifax, and Kingston.

Hingham

is one of the loveliest as well as one of the oldest towns in

Massachusetts (settled in 1633). Its broad main street is shaded by

magnificent elms. Its Old Ship Church, with pyramidal roof and

belfry, dating from 1681, is the oldest existing meetinghouse in the

country, and the quaintest. In the burying ground near it is the

grave of John A. Andrew, the war governor, marked with a

statue by Gould. Comfortable mansions of old type abound in the town.

On a sightly hill is the home of John D. Long, governor,

congressman, and Secretary of the Navy.

Cohasset,

with irregular rocky coast, commanding a wide extent of ocean

prospect, is the most favored place of the upper South Shore for

summer seats. On and about its quite renowned Jerusalem Road are

numerous extensive estates with elaborate houses and grounds. The

Jerusalem Road to an unusual degree blends the charms of

sea

and shore.

Scituate

also enjoys a beautiful ocean front, with fair beaches and a pretty

harbor, protected by rocky cliffs. This town is the scene of

Samuel Woodworth’s lyric, “The Old Oaken Bucket.” The old

farm where the poet was born, which he immortalized in his song, was

close by the present railroad station.

Marshfield

was the country home of Daniel Webster. The Webster place is

some distance from the railroad, eastward. The ride or walk to it is

along a country hillside road, from which beautiful views

occasionally disclose themselves. The place originally included a

part of “Careswell,” the domain of the Plymouth Colony governor,

Edward Winslow. Half a mile back from it is the tomb of Webster,

on Burying Hill, a tranquil spot among fields and pastures

overlooking the sea. Before the tomb, of rough-hewn granite, a plain

marble slab displays the epitaph which Webster dictated the day

before his death (1852). In this inclosure are monuments to early

Pilgrim settlers.

Duxbury,

the home of Elder Brewster, Miles Standish, and John and Priscilla

Alden, is marked by the Standish Monument on Captain’s Hill,

which looms up in the landscape, visible in a wide extent of country

round about. Here is still standing the Standish Cottage,

containing, it is believed, some of the materials of Standish’s own

house, on the slope of Captain’s Hill; and in another part of the

town is the ancient Alden homestead, on the original Alden farm,

which can be seen from the windows of the railroad car. In about the

middle of the village, in the oldest of its burying grounds, the

supposed grave of Standish is marked by a monument, — a

miniature fortress. Here are also graves of the Alden family, and

possibly the grave of Elder Brewster.

Kingston,

part of Plymouth till 1726, when setting up for itself it took its

name of King’s town in honor of George the Second, on his birthday,

is a typical Old Colony town, with a cheerful air of substantiality.

It has a number of interesting landmarks, the most notable being the

Major John Bradford house. Major John was the last of the Bradford

family to possess the Bradford manuscript, now returned from its

adventures and safely housed in the State House at Boston.

|

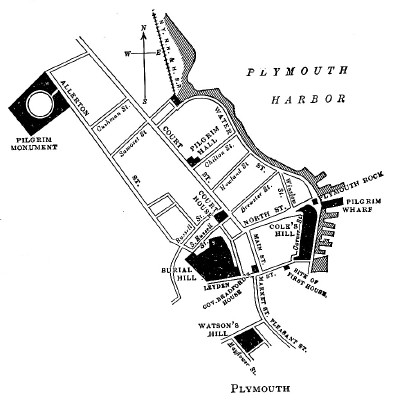

Plymouth

is entered by either the railroad or the trolley line, close to its

historic points. A walk not fatiguing from its length will embrace

them all. If arrival is made by trolley car, the National Monument

is passed at the entrance to the town. It is but a short distance

from the railroad station, and if the visitor comes by train it might

well be visited first, although it is in the opposite direction from

the other Pilgrim sites. The way is through Old Colony Park, a short

tree-lined walk from the rear of the station to Court Street, thence,

to the right, to Cushman Street and to Allerton Street. The great

granite pile, surmounted by the colossal figure of Faith, and with

groups of sitting figures, is seen placed to advantage in a broad

open space on the crown of a hill. It was designed by Hammatt

Billings, and finally completed nearly thirty years after the corner

stone was laid.

Returning

to Court Street and approaching the town center, Pilgrim Hall is

reached, a little way beyond the head of Old Colony Park. In the

front yard is a stone tablet inscribed with the words of the compact

signed in the cabin of the Mayflower. The collection in the

halls of the building, comprising Pilgrim antiquities, paintings,

prints, and other historical objects, is of great extent and value.

Most interesting to many visitors is the Standish case, in which is

the doughty captain’s sword, said to be of early Persian make.

|

|

Above

Pilgrim Hall is the County Court House, on the opposite side

of the street, back from a green park, in which are precious

documents of Pilgrim days. These are preserved in the

office

of the registry of deeds, and include papers bearing the

signatures of Bradford and Standish, orders in Bradford’s

handwriting, Standish’s will, the plan of the first allotment

of lands, the plotting of the first street (t he present Leyden

Street), and the original patent of 1629 granted to Bradford and his

associates.

North

Street, just above the Court House, to the right from Court Street,

leads to Plymouth Rock, under the high granite canopy also

designed by Billings. The side gates in the iron railing are open

during the daytime so that visitors may step upon the stone. Close by

is Pilgrim Wharf.

Cole’s

Hill, where the first houses of the colonists were set up, and

where their first burials were made in unmarked graves, rises from

the opposite side of Water Street, reduced and rounded now from a

ragged elevation to a symmetrical green mound. On the brow is a small

park overlooking the harbor. Here at the head of Middle Street, which

opens from Carver Street, a tablet marks the spot where the skeletons

of two of the forty-four Pilgrims, nearly half the number, who died

during the first hard winter, were found a century and a half after.

These remains, with parts of five other skeletons, are entombed in

the chamber of the canopy over the rock.

Leyden

Street, next beyond Middle Street, the first and chief Pilgrim

street, leads up to Burial Hill. Beyond its start at Carver Street

the site of the first, or “common,” house is seen, marked

conspicuously, on the left side.

Burial

Hill rises abruptly from elm-shaded Town Square, a block from

Main Street, practically a continuation of Court Street. Odd Fellows

Building, on the corner of Main Street, marks the site of Governor

Bradford’s house. The site of the first meetinghouse is

supposed to be covered by the tower of this building. Burial Hill was

the place of the first forts, which served also as

meetinghouses, and these are marked by oval tablets in the burying

ground. The spot where the watch house was erected in 1643 is

similarly marked. The most important monuments here are over the

graves of the Bradfords and of the Cushmans. The Governor Bradford

obelisk occupies a point commanding the fullest view of the town

below. Among other graves of note here are those of John Howland, the

last survivor in Plymouth of the Mayflower passengers, and

Adoniram Judson, the Plymouth minister, father of Adoniram Judson,

the early missionary to Burma.

Watson’s

Hill, where the first Indians appeared to the colonists, and

whence came the friendly Samoset and after him Massasoit, lies to the

southward of Burial Hill. And below is seen the Town Brook

crossing, where Massasoit and his braves were met by the Puritan

leaders, from which meeting resulted the famous “league of peace.”

|