| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’ ‘I suppose you will

be getting away pretty soon, now Full Term is over,

Professor,’ said a person not in the story to the Professor of

Ontography, soon

after they had sat down next to each other at a feast in the hospitable

hall of

St James’s College. The Professor was

young, neat, and precise in speech. ‘Yes,’ he said; ‘my

friends have been making me take up golf this term,

and I mean to go to the East Coast — in point of fact to Burnstow —(I

dare say

you know it) for a week or ten days, to improve my game. I hope to get

off tomorrow.’ ‘Oh, Parkins,’ said

his neighbour on the other side, ‘if you are going

to Burnstow, I wish you would look at the site of the Templars’

preceptory, and

let me know if you think it would be any good to have a dig there in

the

summer.’ It was, as you might

suppose, a person of antiquarian pursuits who said

this, but, since he merely appears in this prologue, there is no need

to give

his entitlements. ‘Certainly,’ said

Parkins, the Professor: ‘if you will describe to me

whereabouts the site is, I will do my best to give you an idea of the

lie of

the land when I get back; or I could write to you about it, if you

would tell

me where you are likely to be.’ ‘Don’t trouble to do

that, thanks. It’s only that I’m thinking of

taking my family in that direction in the Long, and it occurred to me

that, as

very few of the English preceptories have ever been properly planned, I

might

have an opportunity of doing something useful on off-days.’ The Professor rather

sniffed at the idea that planning out a preceptory

could be described as useful. His neighbour continued: ‘The site — I doubt

if there is anything showing above ground — must be

down quite close to the beach now. The sea has encroached tremendously,

as you

know, all along that bit of coast. I should think, from the map, that

it must

be about three-quarters of a mile from the Globe Inn, at the north end

of the

town. Where are you going to stay?’ ‘Well, at

the Globe Inn, as a matter of fact,’ said Parkins; ‘I

have engaged a room there. I couldn’t get in anywhere else; most of the

lodging-houses are shut up in winter, it seems; and, as it is, they

tell me

that the only room of any size I can have is really a double-bedded

one, and

that they haven’t a corner in which to store the other bed, and so on.

But I

must have a fairly large room, for I am taking some books down, and

mean to do

a bit of work; and though I don’t quite fancy having an empty bed — not

to

speak of two — in what I may call for the time being my study, I

suppose I can

manage to rough it for the short time I shall be there.’ ‘Do you call having

an extra bed in your room roughing it, Parkins?’

said a bluff person opposite. ‘Look here, I shall come down and occupy

it for a

bit; it’ll be company for you.’ The Professor

quivered, but managed to laugh in a courteous manner. ‘By all means,

Rogers; there’s nothing I should like better. But I’m

afraid you would find it rather dull; you don’t play golf, do you?’ ‘No, thank Heaven!’

said rude Mr Rogers. ‘Well, you see, when

I’m not writing I shall most likely be out on the

links, and that, as I say, would be rather dull for you, I’m afraid.’ ‘Oh, I don’t know!

There’s certain to be somebody I know in the place;

but, of course, if you don’t want me, speak the word, Parkins; I shan’t

be

offended. Truth, as you always tell us, is never offensive.’ Parkins was, indeed,

scrupulously polite and strictly truthful. It is

to be feared that Mr Rogers sometimes practised upon his knowledge of

these

characteristics. In Parkins’s breast there was a conflict now raging,

which for

a moment or two did not allow him to answer. That interval being over,

he said: ‘Well, if you want

the exact truth, Rogers, I was considering whether

the room I speak of would really be large enough to accommodate us both

comfortably; and also whether (mind, I shouldn’t have said this if you

hadn’t

pressed me) you would not constitute something in the nature of a

hindrance to

my work.’ Rogers laughed

loudly. ‘Well done,

Parkins!’ he said. ‘It’s all right. I promise not to

interrupt your work; don’t you disturb yourself about that. No, I won’t

come if

you don’t want me; but I thought I should do so nicely to keep the

ghosts off.’

Here he might have been seen to wink and to nudge his next neighbour.

Parkins

might also have been seen to become pink. ‘I beg pardon, Parkins,’

Rogers

continued; ‘I oughtn’t to have said that. I forgot you didn’t like

levity on

these topics.’ ‘Well,’ Parkins

said, ‘as you have mentioned the matter, I freely own

that I do not like careless talk about what you call ghosts. A

man in my

position,’ he went on, raising his voice a little, ‘cannot, I find, be

too

careful about appearing to sanction the current beliefs on such

subjects. As

you know, Rogers, or as you ought to know; for I think I have never

concealed

my views —’ ‘No, you certainly

have not, old man,’ put in Rogers sotto voce. ‘— I hold that any

semblance, any appearance of concession to the view

that such things might exist is equivalent to a renunciation of all

that I hold

most sacred. But I’m afraid I have not succeeded in securing your

attention.’ ‘Your undivided

attention, was what Dr Blimber actually said,’1

Rogers interrupted, with every appearance of an earnest desire for

accuracy.

‘But I beg your pardon, Parkins: I’m stopping you.’ ‘No, not at all,’

said Parkins. ‘I don’t remember Blimber; perhaps he

was before my time. But I needn’t go on. I’m sure you know what I mean.’ ‘Yes, yes,’ said

Rogers, rather hastily —‘just so. We’ll go into it

fully at Burnstow, or somewhere.’ In repeating the

above dialogue I have tried to give the impression

which it made on me, that Parkins was something of an old woman —

rather

henlike, perhaps, in his little ways; totally destitute, alas! of the

sense of

humour, but at the same time dauntless and sincere in his convictions,

and a

man deserving of the greatest respect. Whether or not the reader has

gathered

so much, that was the character which Parkins had.

The rest of the

population of the inn was, of course, a golfing one,

and included few elements that call for a special description. The most

conspicuous figure was, perhaps, that of an ancien militaire,

secretary

of a London club, and possessed of a voice of incredible strength, and

of views

of a pronouncedly Protestant type. These were apt to find utterance

after his

attendance upon the ministrations of the Vicar, an estimable man with

inclinations towards a picturesque ritual, which he gallantly kept down

as far

as he could out of deference to East Anglian tradition. Professor Parkins,

one of whose principal characteristics was pluck,

spent the greater part of the day following his arrival at Burnstow in

what he

had called improving his game, in company with this Colonel Wilson: and

during

the afternoon — whether the process of improvement were to blame or

not, I am

not sure — the Colonel’s demeanour assumed a colouring so lurid that

even

Parkins jibbed at the thought of walking home with him from the links.

He

determined, after a short and furtive look at that bristling moustache

and

those incarnadined features, that it would be wiser to allow the

influences of

tea and tobacco to do what they could with the Colonel before the

dinner-hour

should render a meeting inevitable. ‘I might walk home

tonight along the beach,’ he reflected —‘yes, and

take a look — there will be light enough for that — at the ruins of

which

Disney was talking. I don’t exactly know where they are, by the way;

but I

expect I can hardly help stumbling on them.’ This he

accomplished, I may say, in the most literal sense, for in

picking his way from the links to the shingle beach his foot caught,

partly in

a gorse-root and partly in a biggish stone, and over he went. When he

got up

and surveyed his surroundings, he found himself in a patch of somewhat

broken

ground covered with small depressions and mounds. These latter, when he

came to

examine them, proved to be simply masses of flints embedded in mortar

and grown

over with turf. He must, he quite rightly concluded, be on the site of

the

preceptory he had promised to look at. It seemed not unlikely to reward

the

spade of the explorer; enough of the foundations was probably left at

no great

depth to throw a good deal of light on the general plan. He remembered

vaguely

that the Templars, to whom this site had belonged, were in the habit of

building

round churches, and he thought a particular series of the humps or

mounds near

him did appear to be arranged in something of a circular form. Few

people can

resist the temptation to try a little amateur research in a department

quite

outside their own, if only for the satisfaction of showing how

successful they

would have been had they only taken it up seriously. Our Professor,

however, if

he felt something of this mean desire, was also truly anxious to oblige

Mr

Disney. So he paced with care the circular area he had noticed, and

wrote down

its rough dimensions in his pocket-book. Then he proceeded to examine

an oblong

eminence which lay east of the centre of the circle, and seemed to his

thinking

likely to be the base of a platform or altar. At one end of it, the

northern, a

patch of the turf was gone — removed by some boy or other creature ferae

naturae. It might, he thought, be as well to probe the soil here

for

evidences of masonry, and he took out his knife and began scraping away

the

earth. And now followed another little discovery: a portion of soil

fell inward

as he scraped, and disclosed a small cavity. He lighted one match after

another

to help him to see of what nature the hole was, but the wind was too

strong for

them all. By tapping and scratching the sides with his knife, however,

he was

able to make out that it must be an artificial hole in masonry. It was

rectangular, and the sides, top, and bottom, if not actually plastered,

were

smooth and regular. Of course it was empty. No! As he withdrew the

knife he

heard a metallic clink, and when he introduced his hand it met with a

cylindrical object lying on the floor of the hole. Naturally enough, he

picked

it up, and when he brought it into the light, now fast fading, he could

see

that it, too, was of man’s making — a metal tube about four inches

long, and

evidently of some considerable age. By the time Parkins

had made sure that there was nothing else in this

odd receptacle, it was too late and too dark for him to think of

undertaking

any further search. What he had done had proved so unexpectedly

interesting

that he determined to sacrifice a little more of the daylight on the

morrow to

archaeology. The object which he now had safe in his pocket was bound

to be of

some slight value at least, he felt sure. Bleak and solemn was

the view on which he took a last look before

starting homeward. A faint yellow light in the west showed the links,

on which

a few figures moving towards the club-house were still visible, the

squat

martello tower, the lights of Aldsey village, the pale ribbon of sands

intersected at intervals by black wooden groynings, the dim and

murmuring sea.

The wind was bitter from the north, but was at his back when he set out

for the

Globe. He quickly rattled and clashed through the shingle and gained

the sand,

upon which, but for the groynings which had to be got over every few

yards, the

going was both good and quiet. One last look behind, to measure the

distance he

had made since leaving the ruined Templars’ church, showed him a

prospect of

company on his walk, in the shape of a rather indistinct personage, who

seemed

to be making great efforts to catch up with him, but made little, if

any,

progress. I mean that there was an appearance of running about his

movements,

but that the distance between him and Parkins did not seem materially

to

lessen. So, at least, Parkins thought, and decided that he almost

certainly did

not know him, and that it would be absurd to wait until he came up. For

all

that, company, he began to think, would really be very welcome on that

lonely

shore, if only you could choose your companion. In his unenlightened

days he

had read of meetings in such places which even now would hardly bear

thinking

of. He went on thinking of them, however, until he reached home, and

particularly

of one which catches most people’s fancy at some time of their

childhood.’ Now

I saw in my dream that Christian had gone but a very little way when he

saw a

foul fiend coming over the field to meet him.’ ‘What should I do now,’

he

thought, ‘if I looked back and caught sight of a black figure sharply

defined

against the yellow sky, and saw that it had horns and wings? I wonder

whether I

should stand or run for it. Luckily, the gentleman behind is not of

that kind,

and he seems to be about as far off now as when I saw him first. Well,

at this

rate, he won’t get his dinner as soon as I shall; and, dear me! it’s

within a

quarter of an hour of the time now. I must run!’ Parkins had, in

fact, very little time for dressing. When he met the

Colonel at dinner, Peace — or as much of her as that gentleman could

manage —

reigned once more in the military bosom; nor was she put to flight in

the hours

of bridge that followed dinner, for Parkins was a more than respectable

player.

When, therefore, he retired towards twelve o’clock, he felt that he had

spent

his evening in quite a satisfactory way, and that, even for so long as

a

fortnight or three weeks, life at the Globe would be supportable under

similar

conditions —‘especially,’ thought he, ‘if I go on improving my game.’ As he went along the

passages he met the boots of the Globe, who

stopped and said: ‘Beg your pardon,

sir, but as I was abrushing your coat just now there

was something fell out of the pocket. I put it on your chest of

drawers, sir,

in your room, sir — a piece of a pipe or somethink of that, sir. Thank

you,

sir. You’ll find it on your chest of drawers, sir — yes, sir. Good

night, sir.’ The speech served to

remind Parkins of his little discovery of that

afternoon. It was with some considerable curiosity that he turned it

over by

the light of his candles. It was of bronze, he now saw, and was shaped

very

much after the manner of the modern dog-whistle; in fact it was — yes,

certainly it was — actually no more nor less than a whistle. He put it

to his

lips, but it was quite full of a fine, caked-up sand or earth, which

would not

yield to knocking, but must be loosened with a knife. Tidy as ever in

his

habits, Parkins cleared out the earth on to a piece of paper, and took

the

latter to the window to empty it out. The night was clear and bright,

as he saw

when he had opened the casement, and he stopped for an instant to look

at the

sea and note a belated wanderer stationed on the shore in front of the

inn.

Then he shut the window, a little surprised at the late hours people

kept at

Burnstow, and took his whistle to the light again. Why, surely there

were marks

on it, and not merely marks, but letters! A very little rubbing

rendered the

deeply-cut inscription quite legible, but the Professor had to confess,

after

some earnest thought, that the meaning of it was as obscure to him as

the

writing on the wall to Belshazzar. There were legends both on the front

and on

the back of the whistle. The one read thus:

He blew tentatively

and stopped suddenly, startled and yet pleased at

the note he had elicited. It had a quality of infinite distance in it,

and,

soft as it was, he somehow felt it must be audible for miles round. It

was a

sound, too, that seemed to have the power (which many scents possess)

of

forming pictures in the brain. He saw quite clearly for a moment a

vision of a

wide, dark expanse at night, with a fresh wind blowing, and in the

midst a

lonely figure — how employed, he could not tell. Perhaps he would have

seen

more had not the picture been broken by the sudden surge of a gust of

wind

against his casement, so sudden that it made him look up, just in time

to see

the white glint of a seabird’s wing somewhere outside the dark panes. The sound of the

whistle had so fascinated him that he could not help

trying it once more, this time more boldly. The note was little, if at

all,

louder than before, and repetition broke the illusion — no picture

followed, as

he had half hoped it might. “But what is this? Goodness! what force the

wind

can get up in a few minutes! What a tremendous gust! There! I knew that

window-fastening was no use! Ah! I thought so — both candles out. It is

enough

to tear the room to pieces.” The first thing was

to get the window shut. While you might count

twenty Parkins was struggling with the small casement, and felt almost

as if he

were pushing back a sturdy burglar, so strong was the pressure. It

slackened

all at once, and the window banged to and latched itself. Now to

relight the

candles and see what damage, if any, had been done. No, nothing seemed

amiss;

no glass even was broken in the casement. But the noise had evidently

roused at

least one member of the household: the Colonel was to be heard stumping

in his

stockinged feet on the floor above, and growling. Quickly as it had

risen, the

wind did not fall at once. On it went, moaning and rushing past the

house, at

times rising to a cry so desolate that, as Parkins disinterestedly

said, it

might have made fanciful people feel quite uncomfortable; even the

unimaginative, he thought after a quarter of an hour, might be happier

without

it. Whether it was the

wind, or the excitement of golf, or of the

researches in the preceptory that kept Parkins awake, he was not sure.

Awake he

remained, in any case, long enough to fancy (as I am afraid I often do

myself

under such conditions) that he was the victim of all manner of fatal

disorders:

he would lie counting the beats of his heart, convinced that it was

going to

stop work every moment, and would entertain grave suspicions of his

lungs,

brain, liver, etc. — suspicions which he was sure would be dispelled by

the

return of daylight, but which until then refused to be put aside. He

found a

little vicarious comfort in the idea that someone else was in the same

boat. A

near neighbour (in the darkness it was not easy to tell his direction)

was

tossing and rustling in his bed, too. The next stage was

that Parkins shut his eyes and determined to give

sleep every chance. Here again over-excitement asserted itself in

another form

— that of making pictures. Experto crede, pictures do come to

the closed

eyes of one trying to sleep, and are often so little to his taste that

he must

open his eyes and disperse them. Parkins’s experience

on this occasion was a very distressing one. He

found that the picture which presented itself to him was continuous.

When he

opened his eyes, of course, it went; but when he shut them once more it

framed

itself afresh, and acted itself out again, neither quicker nor slower

than

before. What he saw was this: A long stretch of

shore — shingle edged by sand, and intersected at

short intervals with black groynes running down to the water — a scene,

in

fact, so like that of his afternoon’s walk that, in the absence of any

landmark, it could not be distinguished therefrom. The light was

obscure,

conveying an impression of gathering storm, late winter evening, and

slight

cold rain. On this bleak stage at first no actor was visible. Then, in

the distance,

a bobbing black object appeared; a moment more, and it was a man

running,

jumping, clambering over the groynes, and every few seconds looking

eagerly

back. The nearer he came the more obvious it was that he was not only

anxious,

but even terribly frightened, though his face was not to be

distinguished. He

was, moreover, almost at the end of his strength. On he came; each

successive

obstacle seemed to cause him more difficulty than the last. ‘Will he

get over

this next one?’ thought Parkins; ‘it seems a little higher than the

others.’

Yes; half climbing, half throwing himself, he did get over, and fell

all in a

heap on the other side (the side nearest to the spectator). There, as

if really

unable to get up again, he remained crouching under the groyne, looking

up in

an attitude of painful anxiety. So far no cause

whatever for the fear of the runner had been shown; but

now there began to be seen, far up the shore, a little flicker of

something

light-coloured moving to and fro with great swiftness and irregularity.

Rapidly

growing larger, it, too, declared itself as a figure in pale,

fluttering

draperies, ill-defined. There was something about its motion which made

Parkins

very unwilling to see it at close quarters. It would stop, raise arms,

bow

itself towards the sand, then run stooping across the beach to the

water-edge

and back again; and then, rising upright, once more continue its course

forward

at a speed that was startling and terrifying. The moment came when the

pursuer

was hovering about from left to right only a few yards beyond the

groyne where

the runner lay in hiding. After two or three ineffectual castings

hither and

thither it came to a stop, stood upright, with arms raised high, and

then

darted straight forward towards the groyne.

The scraping of

match on box and the glare of light must have startled

some creatures of the night — rats or what not — which he heard scurry

across

the floor from the side of his bed with much rustling. Dear, dear! the

match is

out! Fool that it is! But the second one burnt better, and a candle and

book

were duly procured, over which Parkins pored till sleep of a wholesome

kind

came upon him, and that in no long space. For about the first time in

his

orderly and prudent life he forgot to blow out the candle, and when he

was called

next morning at eight there was still a flicker in the socket and a sad

mess of

guttered grease on the top of the little table. After breakfast he

was in his room, putting the finishing touches to

his golfing costume — fortune had again allotted the Colonel to him for

a

partner — when one of the maids came in. ‘Oh, if you please,’

she said, ‘would you like any extra blankets on

your bed, sir?’ ‘Ah! thank you,’

said Parkins. ‘Yes, I think I should like one. It

seems likely to turn rather colder.’ In a very short time

the maid was back with the blanket. ‘Which bed should I

put it on, sir?’ she asked. ‘What? Why, that one

— the one I slept in last night,’ he said,

pointing to it. ‘Oh yes! I beg your

pardon, sir, but you seemed to have tried both of

’em; leastways, we had to make ’em both up this morning.’ ‘Really? How very

absurd!’ said Parkins. ‘I certainly never touched the

other, except to lay some things on it. Did it actually seem to have

been slept

in?’ ‘Oh yes, sir!’ said

the maid. ‘Why, all the things was crumpled and

throwed about all ways, if you’ll excuse me, sir — quite as if anyone

‘adn’t

passed but a very poor night, sir.’ ‘Dear me,’ said

Parkins. ‘Well, I may have disordered it more than I

thought when I unpacked my things. I’m very sorry to have given you the

extra

trouble, I’m sure. I expect a friend of mine soon, by the way — a

gentleman

from Cambridge — to come and occupy it for a night or two. That will be

all

right, I suppose, won’t it?’ ‘Oh yes, to be sure,

sir. Thank you, sir. It’s no trouble, I’m sure,’

said the maid, and departed to giggle with her colleagues. Parkins set forth,

with a stern determination to improve his game. I am glad to be able

to report that he succeeded so far in this

enterprise that the Colonel, who had been rather repining at the

prospect of a

second day’s play in his company, became quite chatty as the morning

advanced;

and his voice boomed out over the flats, as certain also of our own

minor poets

have said, ‘like some great bourdon in a minster tower’. ‘Extraordinary wind,

that, we had last night,’ he said. ‘In my old home

we should have said someone had been whistling for it.’ ‘Should you,

indeed!’ said Perkins. ‘Is there a superstition of that

kind still current in your part of the country?’ ‘I don’t know about

superstition,’ said the Colonel. ‘They believe in

it all over Denmark and Norway, as well as on the Yorkshire coast; and

my

experience is, mind you, that there’s generally something at the bottom

of what

these country-folk hold to, and have held to for generations. But it’s

your

drive’ (or whatever it might have been: the golfing reader will have to

imagine

appropriate digressions at the proper intervals). When conversation

was resumed, Parkins said, with a slight hesitancy: ‘A propos of what

you were saying just now, Colonel, I think I ought to

tell you that my own views on such subjects are very strong. I am, in

fact, a

convinced disbeliever in what is called the “supernatural”.’ ‘What!’ said the

Colonel, ‘do you mean to tell me you don’t believe in

second-sight, or ghosts, or anything of that kind?’ ‘In nothing whatever

of that kind,’ returned Parkins firmly. ‘Well,’ said the

Colonel, ‘but it appears to me at that rate, sir, that

you must be little better than a Sadducee.’ Parkins was on the

point of answering that, in his opinion, the

Sadducees were the most sensible persons he had ever read of in the Old

Testament; but feeling some doubt as to whether much mention of them

was to be

found in that work, he preferred to laugh the accusation off. ‘Perhaps I am,’ he

said; ‘but — Here, give me my cleek, boy! — Excuse

me one moment, Colonel.’ A short interval. ‘Now, as to whistling for

the wind,

let me give you my theory about it. The laws which govern winds are

really not

at all perfectly known — to fisherfolk and such, of course, not known

at all. A

man or woman of eccentric habits, perhaps, or a stranger, is seen

repeatedly on

the beach at some unusual hour, and is heard whistling. Soon afterwards

a

violent wind rises; a man who could read the sky perfectly or who

possessed a

barometer could have foretold that it would. The simple people of a

fishing-village have no barometers, and only a few rough rules for

prophesying

weather. What more natural than that the eccentric personage I

postulated

should be regarded as having raised the wind, or that he or she should

clutch

eagerly at the reputation of being able to do so? Now, take last

night’s wind:

as it happens, I myself was whistling. I blew a whistle twice, and the

wind

seemed to come absolutely in answer to my call. If anyone had seen me —’ The audience had

been a little restive under this harangue, and Parkins

had, I fear, fallen somewhat into the tone of a lecturer; but at the

last

sentence the Colonel stopped. ‘Whistling, were

you?’ he said. ‘And what sort of whistle did you use?

Play this stroke first.’ Interval. ‘About that whistle

you were asking, Colonel. It’s rather a curious

one. I have it in my — No; I see I’ve left it in my room. As a matter

of fact,

I found it yesterday.’ And then Parkins

narrated the manner of his discovery of the whistle,

upon hearing which the Colonel grunted, and opined that, in Parkins’s

place, he

should himself be careful about using a thing that had belonged to a

set of

Papists, of whom, speaking generally, it might be affirmed that you

never knew

what they might not have been up to. From this topic he diverged to the

enormities of the Vicar, who had given notice on the previous Sunday

that

Friday would be the Feast of St Thomas the Apostle, and that there

would be

service at eleven o’clock in the church. This and other similar

proceedings

constituted in the Colonel’s view a strong presumption that the Vicar

was a

concealed Papist, if not a Jesuit; and Parkins, who could not very

readily

follow the Colonel in this region, did not disagree with him. In fact,

they got

on so well together in the morning that there was not talk on either

side of

their separating after lunch. Both continued to

play well during the afternoon, or at least, well

enough to make them forget everything else until the light began to

fail them.

Not until then did Parkins remember that he had meant to do some more

investigating at the preceptory; but it was of no great importance, he

reflected. One day was as good as another; he might as well go home

with the Colonel. As they turned the

corner of the house, the Colonel was almost knocked

down by a boy who rushed into him at the very top of his speed, and

then,

instead of running away, remained hanging on to him and panting. The

first

words of the warrior were naturally those of reproof and objurgation,

but he

very quickly discerned that the boy was almost speechless with fright.

Inquiries were useless at first. When the boy got his breath he began

to howl,

and still clung to the Colonel’s legs. He was at last detached, but

continued

to howl. ‘What in the world

is the matter with you? What have you been up to?

What have you seen?’ said the two men. ‘Ow, I seen it wive

at me out of the winder,’ wailed the boy, ‘and I

don’t like it.’ ‘What window?’ said

the irritated Colonel. ‘Come pull yourself

together, my boy.’ ‘The front winder it

was, at the ‘otel,’ said the boy. At this point

Parkins was in favour of sending the boy home, but the

Colonel refused; he wanted to get to the bottom of it, he said; it was

most

dangerous to give a boy such a fright as this one had had, and if it

turned out

that people had been playing jokes, they should suffer for it in some

way. And

by a series of questions he made out this story: The boy had been

playing about

on the grass in front of the Globe with some others; then they had gone

home to

their teas, and he was just going, when he happened to look up at the

front

winder and see it a-wiving at him. It seemed to be a figure of

some

sort, in white as far as he knew — couldn’t see its face; but it wived

at him,

and it warn’t a right thing — not to say not a right person. Was there

a light

in the room? No, he didn’t think to look if there was a light. Which

was the

window? Was it the top one or the second one? The seckind one it was —

the big

winder what got two little uns at the sides. ‘Very well, my boy,’

said the Colonel, after a few more questions. ‘You

run away home now. I expect it was some person trying to give you a

start.

Another time, like a brave English boy, you just throw a stone — well,

no, not

that exactly, but you go and speak to the waiter, or to Mr Simpson, the

landlord, and — yes — and say that I advised you to do so.’ The boy’s face

expressed some of the doubt he felt as to the likelihood

of Mr Simpson’s lending a favourable ear to his complaint, but the

Colonel did

not appear to perceive this, and went on: ‘And here’s a

sixpence — no, I see it’s a shilling — and you be off

home, and don’t think any more about it.’ The youth hurried

off with agitated thanks, and the Colonel and Parkins

went round to the front of the Globe and reconnoitred. There was only

one

window answering to the description they had been hearing. ‘Well, that’s

curious,’ said Parkins; ‘it’s evidently my window the lad

was talking about. Will you come up for a moment, Colonel Wilson? We

ought to

be able to see if anyone has been taking liberties in my room.’ They were soon in

the passage, and Parkins made as if to open the door.

Then he stopped and felt in his pockets. ‘This is more

serious than I thought,’ was his next remark. ‘I remember

now that before I started this morning I locked the door. It is locked

now,

and, what is more, here is the key.’ And he held it up. ‘Now,’ he went

on, ‘if

the servants are in the habit of going into one’s room during the day

when one

is away, I can only say that — well, that I don’t approve of it at

all.’

Conscious of a somewhat weak climax, he busied himself in opening the

door

(which was indeed locked) and in lighting candles. ‘No,’ he said,

‘nothing

seems disturbed.’ ‘Except your bed,’

put in the Colonel. ‘Excuse me, that

isn’t my bed,’ said Parkins. ‘I don’t use that one.

But it does look as if someone had been playing tricks with it.’ It certainly did:

the clothes were bundled up and twisted together in a

most tortuous confusion. Parkins pondered. ‘That must be it,’

he said at last. ‘I disordered the clothes last

night in unpacking, and they haven’t made it since. Perhaps they came

in to

make it, and that boy saw them through the window; and then they were

called

away and locked the door after them. Yes, I think that must be it.’ ‘Well, ring and

ask,’ said the Colonel, and this appealed to Parkins as

practical. The maid appeared,

and, to make a long story short, deposed that she

had made the bed in the morning when the gentleman was in the room, and

hadn’t

been there since. No, she hadn’t no other key. Mr Simpson, he kep’ the

keys;

he’d be able to tell the gentleman if anyone had been up. This was a puzzle.

Investigation showed that nothing of value had been

taken, and Parkins remembered the disposition of the small objects on

tables

and so forth well enough to be pretty sure that no pranks had been

played with

them. Mr and Mrs Simpson furthermore agreed that neither of them had

given the

duplicate key of the room to any person whatever during the day. Nor

could

Parkins, fair-minded man as he was, detect anything in the demeanour of

master,

mistress, or maid that indicated guilt. He was much more inclined to

think that

the boy had been imposing on the Colonel. The latter was

unwontedly silent and pensive at dinner and throughout

the evening. When he bade goodnight to Parkins, he murmured in a gruff

undertone: ‘You know where I am

if you want me during the night.’ ‘Why, yes, thank

you, Colonel Wilson, I think I do; but there isn’t much

prospect of my disturbing you, I hope. By the way,’ he added, ‘did I

show you

that old whistle I spoke of? I think not. Well, here it is.’ The Colonel turned

it over gingerly in the light of the candle. ‘Can you make

anything of the inscription?’ asked Parkins, as he took

it back. ‘No, not in this

light. What do you mean to do with it?’ ‘Oh, well, when I

get back to Cambridge I shall submit it to some of

the archaeologists there, and see what they think of it; and very

likely, if

they consider it worth having, I may present it to one of the museums.’ ‘M!’ said the

Colonel. ‘Well, you may be right. All I know is that, if

it were mine, I should chuck it straight into the sea. It’s no use

talking, I’m

well aware, but I expect that with you it’s a case of live and learn. I

hope

so, I’m sure, and I wish you a good night.’ He turned away,

leaving Parkins in act to speak at the bottom of the

stair, and soon each was in his own bedroom. By some unfortunate

accident, there were neither blinds nor curtains to

the windows of the Professor’s room. The previous night he had thought

little

of this, but tonight there seemed every prospect of a bright moon

rising to

shine directly on his bed, and probably wake him later on. When he

noticed this

he was a good deal annoyed, but, with an ingenuity which I can only

envy, he

succeeded in rigging up, with the help of a railway-rug, some

safety-pins, and

a stick and umbrella, a screen which, if it only held together, would

completely keep the moonlight off his bed. And shortly afterwards he

was

comfortably in that bed. When he had read a somewhat solid work long

enough to

produce a decided wish to sleep, he cast a drowsy glance round the

room, blew

out the candle, and fell back upon the pillow. He must have slept

soundly for an hour or more, when a sudden clatter

shook him up in a most unwelcome manner. In a moment he realized what

had

happened: his carefully-constructed screen had given way, and a very

bright

frosty moon was shining directly on his face. This was highly annoying.

Could

he possibly get up and reconstruct the screen? or could he manage to

sleep if

he did not? For some minutes he

lay and pondered over all the possibilities; then

he turned over sharply, and with his eyes open lay breathlessly

listening.

There had been a movement, he was sure, in the empty bed on the

opposite side

of the room. Tomorrow he would have it moved, for there must be rats or

something playing about in it. It was quiet now. No! the commotion

began again.

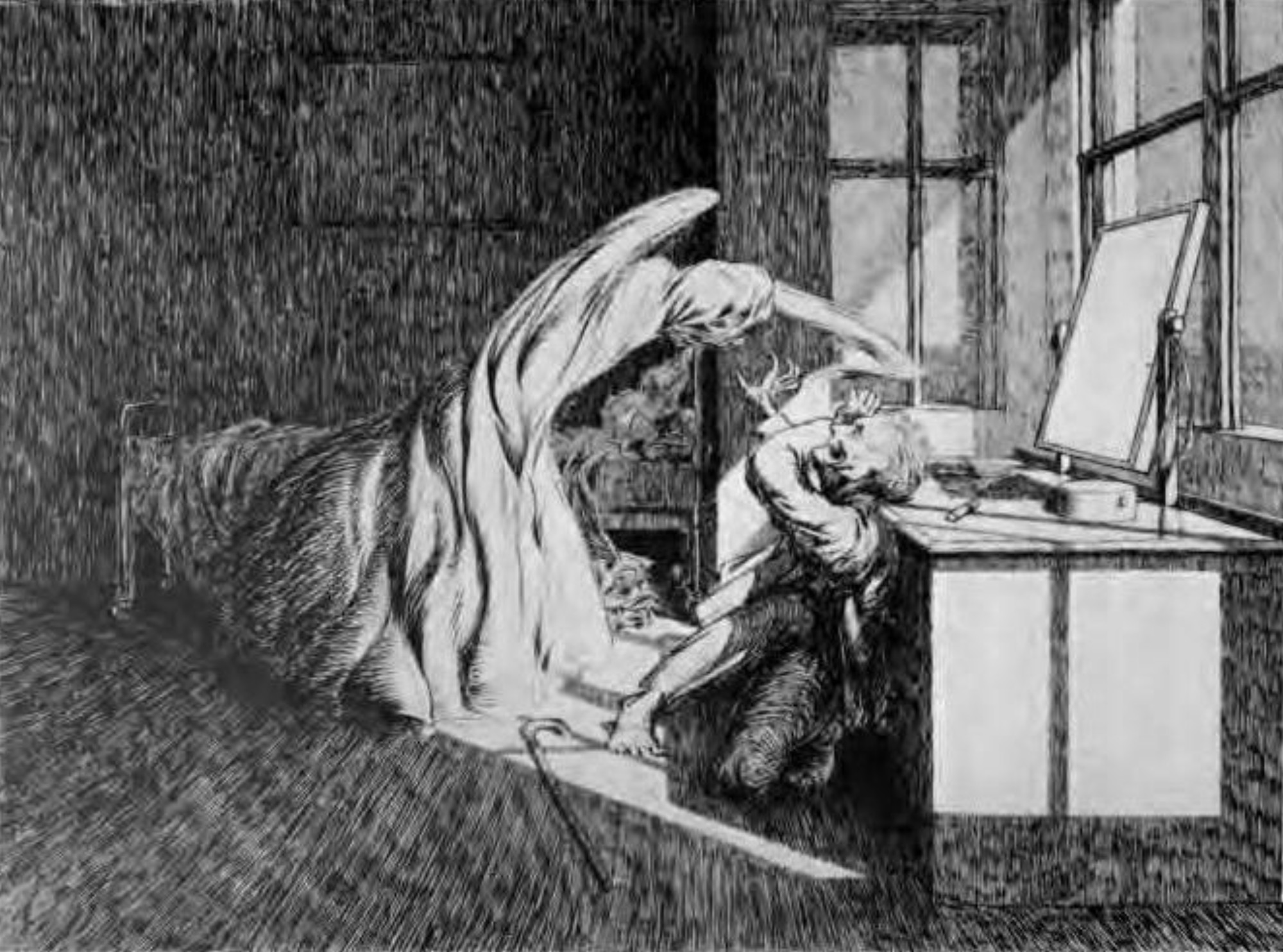

There was a rustling and shaking: surely more than any rat could cause. I can figure to

myself something of the Professor’s bewilderment and

horror, for I have in a dream thirty years back seen the same thing

happen; but

the reader will hardly, perhaps, imagine how dreadful it was to him to

see a

figure suddenly sit up in what he had known was an empty bed. He was

out of his

own bed in one bound, and made a dash towards the window, where lay his

only

weapon, the stick with which he had propped his screen. This was, as it

turned

out, the worst thing he could have done, because the personage in the

empty

bed, with a sudden smooth motion, slipped from the bed and took up a

position,

with outspread arms, between the two beds, and in front of the door.

Parkins

watched it in a horrid perplexity. Somehow, the idea of getting past it

and

escaping through the door was intolerable to him; he could not have

borne — he

didn’t know why — to touch it; and as for its touching him, he would

sooner

dash himself through the window than have that happen. It stood for the

moment

in a band of dark shadow, and he had not seen what its face was like.

Now it

began to move, in a stooping posture, and all at once the spectator

realized,

with some horror and some relief, that it must be blind, for it seemed

to feel

about it with its muffled arms in a groping and random fashion. Turning

half

away from him, it became suddenly conscious of the bed he had just

left, and

darted towards it, and bent and felt over the pillows in a way which

made

Parkins shudder as he had never in his life thought it possible. In a

very few

moments it seemed to know that the bed was empty, and then, moving

forward into

the area of light and facing the window, it showed for the first time

what

manner of thing it was. Parkins, who very

much dislikes being questioned about it, did once

describe something of it in my hearing, and I gathered that what he

chiefly

remembers about it is a horrible, an intensely horrible, face of

crumpled

linen. What expression he read upon it he could not or would not

tell, but

that the fear of it went nigh to maddening him is certain. But he was not at

leisure to watch it for long. With formidable

quickness it moved into the middle of the room, and, as it groped and

waved,

one corner of its draperies swept across Parkins’s face. He could not,

though

he knew how perilous a sound was — he could not keep back a cry of

disgust, and

this gave the searcher an instant clue. It leapt towards him upon the

instant,

and the next moment he was half-way through the window backwards,

uttering cry

upon cry at the utmost pitch of his voice, and the linen face was

thrust close

into his own. At this, almost the last possible second, deliverance

came, as

you will have guessed: the Colonel burst the door open, and was just in

time to

see the dreadful group at the window. When he reached the figures only

one was

left. Parkins sank forward into the room in a faint, and before him on

the

floor lay a tumbled heap of bed-clothes. Colonel Wilson asked

no questions, but busied himself in keeping

everyone else out of the room and in getting Parkins back to his bed;

and

himself, wrapped in a rug, occupied the other bed, for the rest of the

night.

Early on the next day Rogers arrived, more welcome than he would have

been a

day before, and the three of them held a very long consultation in the

Professor’s room. At the end of it the Colonel left the hotel door

carrying a

small object between his finger and thumb, which he cast as far into

the sea as

a very brawny arm could send it. Later on the smoke of a burning

ascended from

the back premises of the Globe.

There is not much

question as to what would have happened to Parkins if

the Colonel had not intervened when he did. He would either have fallen

out of

the window or else lost his wits. But it is not so evident what more

the

creature that came in answer to the whistle could have done than

frighten.

There seemed to be absolutely nothing material about it save the

bedclothes of

which it had made itself a body. The Colonel, who remembered a not very

dissimilar occurrence in India, was of the opinion that if Parkins had

closed

with it it could really have done very little, and that its one power

was that

of frightening. The whole thing, he said, served to confirm his opinion

of the

Church of Rome. There is really

nothing more to tell, but, as you may imagine, the

Professor’s views on certain points are less clear cut than they used

to be.

His nerves, too, have suffered: he cannot even now see a surplice

hanging on a

door quite unmoved, and the spectacle of a scarecrow in a field late on

a

winter afternoon has cost him more than one sleepless night. |