| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2005 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2005 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to |

| Order A Print Copy Here |

ONCE

UPON A TIME

By LEILA M. WELLS

Illustrated by

Sister Mary

Felicitas, R.S.M.

|

DREAMS

Dreams are such wonderous things And always surpassing fair, Not much like what life brings to us Of trials and sorrow and care. In the years of youth I dreamed fair dreams Of the wonderful things I’d do; But in the eyes of the world today Not one of those dreams came true. But as I sit and backward look, How wonderful it seems That God has sent more marvelous things Than ever was in my dreams. – Leila

M.

Wells

|

Republished

by Kellscraft Studio

2005

Originally

printed by the

Denton

Publications, Inc.

Elizabethtown,

N. Y.

1971

ONCE

UPON A TIME

I was born October 29, 1880, in a room in John Brown’s farm-house in the town of North Elba, Essex County, New York, not many miles from the famous resort of Lake Placid and almost in sight of the world-renowned Mount Van Hoevenburg Bobsled Run.

My first nine years were lived in the village of Lake Placid and I’ve watched it grow through the years from a small hamlet with only one school, two stores, one church, and a blacksmith shop until now, with a full-time mayor and world-renown.

I started school when I was six and had to walk more than a mile to the one-room schoolhouse where there were over thirty boys and girls of all ages. We had separate recesses as there was only one toilet and that was small and across the yard from the schoolhouse. The teacher believed in the “hickory stick” method of teaching and I was afraid of him.

The next year I went to a select school nearer home in the top floor of a boathouse on the shore of Mirror Lake. After two years there the first schoolhouse was built in the village of Lake Placid and I had only to run across the road to be in the school yard.

That one-room building was soon outgrown and additions were made until now it has grown into one of the largest central schools in the county.

My father was an Adirondack guide and told us some interesting experiences of his life in the woods. He told about taking a party of college boys up Mount Marcy once on July 7th and they found a large drift of snow and had a snowball fight. Years after, he picked up a hitchhiker and the man told him about the snowball fight he had once had on Mount Marcy in July with some of his college mates. He was surprised when Dad said that he remembered the occasion.

Later my father bought a small steamboat and took the city people on excursions around Lake Placid. During the winter months he earned whatever he could, doing any work he could find. One winter he ran a shingle machine at the sawmill. He worked at night as the machine couldn’t operate if the sawmill was working. He received fifty cents for the night.

My mother loved flowers and had a lot of them. In fact she was the first florist in Lake Placid and sold many flowers to the city visitors.

The year that Grover Cleveland was married he came to Lake Placid on his honeymoon and stayed at the Grand View Hotel. Of course everyone went to see the president. My mother couldn’t go as she was pregnant and in those days a pregnant woman stayed at home, so she fixed three bouquets (corsages) and my father took them to the hotel for President and Mrs. Cleveland and her mother who was with them. They wore them at the big ball that was given for them that night, and the next day the three of them came to thank my mother for the flowers and to admire her garden. There was a great demand that year for sweet peas, nasturtiums, and double poppies as they were the flowers worn by the president’s party.

A trip to Grandpa’s was something to remember. He lived in a nail log house near Great-grandma’s bigger one which he moved to after his mother died. The small house is gone now but the her still stands and is occupied in summer and has been modernized inside.

The small log cabin had only one room and an outside summer kitchen. There was a bed in one corner and it had a “trundle” bed underneath it which was always occupied until they moved into the larger house as there were eight children in the family. My mother was the oldest and the youngest child was only three weeks older than I.

Grandfather drove a yoke of oxen and I can remember how proud we all were when he bought a horse and wagon. The wagon was short between the wheels and hadn’t any springs. Some years later he traded it for a buckboard.

My father’s father was an engineer of sorts, as he never went to school but a very little but he had natural ability. He moved buildings and built roads.

The road in Keene, Essex County, New York, that passes the Cascade Lakes was one of his jobs. Very few people thought a road could be built there but he was sure it could be done thus saving many miles between Keene and North Elba, and bringing some of nature’s beauty into evidence. Years ago it was a one-lane road with meeting places within sight of each other. If two teams met between these “turning out” places one had to back up to let the other pass.

Once when my father and I were going over that road in the winter we found it badly drifted so the lakes were being used as the highway because the ice was clear of snow. Just as we were ready to drive onto the ice we saw a team coming towards us and one of the horses was just scrambling out of the water as it had broken through a thin place in the ice.

Now this road is a state highway revealing the beauty of Adirondack lakes.

Music is composed of sounds but not all sounds produce music.

As one listens to the radio or the Hi-fi today one can not realize what the invention of the phonograph meant a century ago.

Musical instruments date back to Bible times but very few of the ones used then are still used except the harp and maybe the drums and the cymbals.

The Jew’s harp and the mouth organ are almost never heard now-a-days though occasionally one hears a harmonica. Violins (fiddles) and banjos have been replaced by the electric guitar.

In the good old days, many children knew music only by the songs that they heard sung by some relative and the hymns that were sung in Sunday School and during the church service.

My first music, produced mechanically, was the hand-organ man’s as he turned a crank for his monkey to perform and collect pennies in his little red cap.

Soon after this my mother acquired a small “music box.” This was a small box with rollers which produced a tune from a cylinder which had little brass pegs which hit little notes as one turned the crank.

The next music was one of Edison’s phonographs with wax rolls and ear “phones.” A large horn was obtained later so that more people could listen at one time.

Who remembers the old ad of a dog listening to “His Master’s Voice?”

Victrolas, hand operated, were next in line with flat records, forerunners of today’s hi-fi.

It was a proud family when an organ was brought into the home and some of the family could “play by ear.”

A family who could afford a piano was indeed the envy of the whole neighborhood.

Most of the old “fiddlers” didn’t know one note from another and often the fiddle was handed down for several generations.

Often very young children could play the violin real well by ear. “Fiddlers” contests were one of the old time entertainments often followed by a square dance.

The music teacher was often the church organist.

Years ago in our town there used to be a “singing school” taught one night a week during the winter. This was one form of “get together” that was beneficial. At the close of the term a concert was given. Our book was called “The Key Letter” and I was the youngest in the school but didn’t really learn to sing and I never learned to play the organ, although we had an old Mason and Hamlin organ.

This was considered one of the best makes and the Estey was a close second. The early pianos were cumbersome affairs and only people with a large parlor could have them.

The school bands of today are very different from the village bands of the good old days.

PEDDLERS

How many today remember the old peddlers who used to travel through this North Country with their wares?

The first ones I remember were the “tin peddlers.” You could hear them coming and await their arrival with anticipation.

His outfit consisted of a rather rickety wagon with a high box behind the seat and drawn by a rather sad looking horse.

His wares were mostly tin ware – pie and cake tins, bread tins, pails of all sorts and sizes, dust pans – and nearly everything that could be made of tin, and mostly hand made and soldered.

The outside was generally adorned with hand made brooms and mop handles.

“Old Blind Foster” was the only peddler I especially remember in the 1880’s. He usually came in the spring and had a boy to drive for him. His specialty was brooms. He made them himself during the winter, and a Foster broom lasted more than a year – and cost a quarter.

Next came the pack peddlers. They were emigrants who had to have some means of support before they could enter this country. They could speak very little English, but learned fast.

Their packs at first were mostly boxes twelve or eighteen inches square and about the same in depth. Their stock consisted mostly of pins and needles, thimbles and cheap jewelry. As they gained in knowing what people needed and wanted and could afford to buy, their stock grew until they were really quite like travelling dry goods stores, and one wondered how they could carry such packs. Their packs were wrapped in a large piece of bed-ticking, with one or two leather straps holding the contents in place and giving them something to hold them firmly on their backs.

One who used to stay overnight at our house was named Simon and he was a Russian, who came to America to escape military service. He had a Russian-American dictionary and he could find a Russian word and then ask one of us children to pronounce the English word, and then he’d say it over and over.

He was a “violinist” not a “fiddler.” I never heard such music he could make even on a poor violin.

Another pack peddler was named Isaac and he progressed rapidly in English and prosperity and in his later years owned and operated a dry-goods store in Port Henry.

Each peddler was welcomed by the farm wives as they seldom went to the store even to buy the groceries and had little chance to see new dry goods.

LIGHTS

And God said let there be light and there was light!

When you’ve pushed a button or turned a switch in the darkness and light appeared, have you ever thought how wonderful is light?

How did the people produce light in Bible times? We know they used torches but how did they light them?

We know that the Pilgrims used to bury coals in the ashes so as to keep their fires for the next day and sometimes if they went out, someone went to the nearest neighbor to borrow a few coals if no one had a flint and tinder.

Who discovered that a piece of flint struck against steel would make a spark that would start a fire if that spark fell upon the right substance? What a wonderful discovery!

Before matches were invented, rolls of paper or splinters of dry wood were used for lighting candles and lamps. The first lamps were dishes of oil with a piece of cloth in it which gave a small light as it burned.

The first lanterns were of tin with holes in the sides and a candle inside.

The first candles were made from bees wax but later were made from the fat from bears and sheep.

Our ancestors made their candles by dipping heavy cord into the fat, letting it cool and dipping again and again until the candle was at least an inch through.

Later there were candle molds of tin so at least ten or twelve could be made at one time.

When one sees the fine sewing, quilting and embroidering done by the early pioneers, one wonders how they could do such fine work with only a candle or oil lamp for light.

CHRISTMAS

IN THE

1880’s

Christmas, then as now, came but once a year, but I think it had more meaning to the children of that time than to the ones of today.

In the first place, we had only one Christmas while today’s children have Christmas from Thanksgiving until after the real day has passed. They have parties and trees and gifts galore.

Our Christmas was just one tree and not many presents. Our tree was a big one, reaching nearly to the ceiling of the church and was decorated mostly with strings of popcorn and oranges hung by a string and gifts.

Gifts were not wrapped in fancy paper, tied with yards of ribbon and placed under the tree.

Generally the largest and prettiest doll was hung as high up as branch could be found to hold it and the girl who received it was the envy of all the others.

Our Christmases would have been rather slim if it hadn’t been for the “city people” who made a practice of sending gifts for each Sunday School child.

One Christmas I especially remember, we each received a pocketbook with a silver dollar in it. The three of us gave our dollar to our father so he could buy himself a pair of pants so he’d have something fit to wear to church. My brother lost his pocketbook that summer but my sister and I had ours for years. As we didn’t have much use for them, not having much money, they lasted quite a while.

Another Christmas, in fact for several, books were sent. I still have one that I received then. I remember the Christmas that I received a “Cheerful Chatter” and a box of water color paints. That winter we were house-bound and Mother let my sister and me paint the pictures in that book. It is now a treasured possession of my sister’s granddaughter.

Although living in a place where trees were abundant, no one thought of having a private tree nor of decorating the house with evergreens as today.

I wonder how many of today’s children ever strung popcorn for decorating a Christmas tree. A needle was threaded with about two yards of heavy white thread – No. 8 or 10 (You can’t find it in today’s stores) – and kernels of the lovely white stuff were strung until it would hold no more. It’s lots prettier than the tinsel used today. After the tree was bare of presents, the strings of popcorn were eaten by the children. Sanitation was unheard of then.

Another decoration for the tree were the net stockings made by the church ladies and filled with popcorn, peanuts, and hard candy – one for each child.

We moved away from Lake Placid in the spring of 1889, so I don’t know when the changes came, but I do know that Christmas isn’t now like it used to be. Merry Christmas to all.

CONVENIENCES

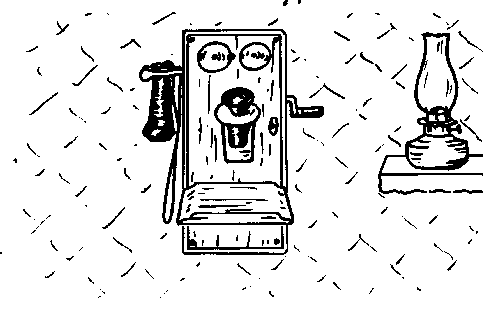

Sometimes we damn the telephone especially if it rings at an inconvenient time but think what you’d do if you didn’t have one.

They didn’t come into general use until the beginning of the present century.

I can remember how wonderful it seemed to talk with my parents yet couldn’t see them.

Telephones are a wonderful time saver. Before they came into use, if one needed a doctor a messenger had to go miles with a horse and buggy or horseback to get one.

My mother used to tell us how her mother sent her a child of three, with a note to her grandmother at the time when her sister was born. She and her little dog went more than a mile through the woods. Think of grandma’s anxiety, wondering if her child could make it safely and if her mother would arrive before the baby did.

Did you ever wonder what people did before they had electricity? There are still a few homes without it but they are few and far between.

Light is the most important of the gifts of electricity but power comes next. Just sit down and make a list of the uses you make of it and be thankful that Ben Franklin and Tom Edison once lived in our dear U.S.A.

Gasoline comes next in usefulness but the uses seem to help the men more than the women, tho about as many women drive cars as men.

The lawn mower is one of the greatest conveniences powered by gasoline.

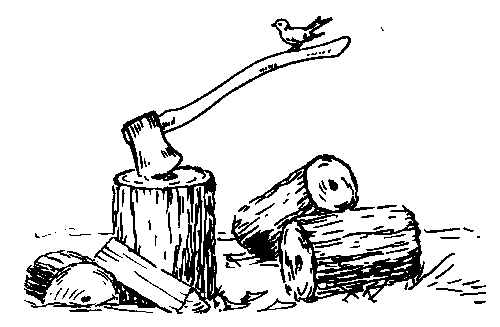

How our fathers, and especially our grandfathers, would have appreciated the chainsaw. Now that the chainsaw is in, it has done away with the buck saw, the axe, and crosscut saw which they used in cutting logs and firewood.

Fuel oil is another convenience as in days of yore wood was the only fuel used in this north country and its preparation was a long, hard process.

Getting “the year’s supply of wood” generally started in November, before the snow got very deep.

A provident man was judged by the amount of wood in the wood shed.

After the trees were chopped down with an axe, they were chopped or sawed into four feet lengths for easier handling and drawn to the wood shed where they could be sawed into “stove length” with a buck saw.

And then the axe was used again to split the blocks into convenient size for the cook stove or range. Some blocks were left for the heater or “box stove.”

After gasoline came into use someone invented a “power saw” which could be moved from place to place and did away with the “buck” saw as its owner did “custom” sawing.

A cord of wood was four feet wide, four feet high and eight feet in length and in those days could be bought for four or five dollars a cord.

WHAT’S

THAT?

Several years ago I visited a museum with a group of young people and “What’s That” was a very frequent question and in the years to come more and more young people, and some not so young, will be asking that question whenever they enter a museum or an antique shop.

And then again, I wonder. Will there be some of our old necessities still in existence as houses grow smaller and less storage space is available. “Throw it out.” “It isn’t of any use.” “That’s just junk.”

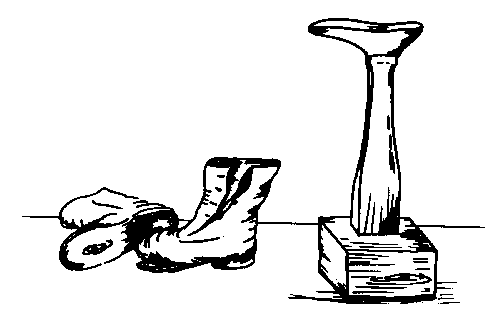

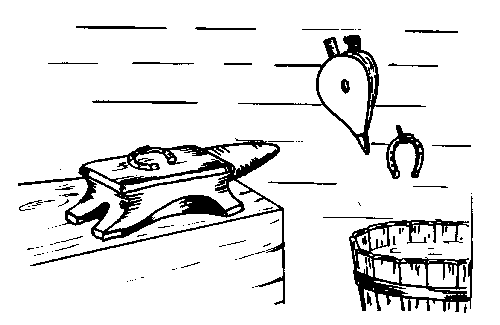

“What’s that?” asked one as we looked at an old cobbler’s bench with wooden lasts, pegs and a hammer. When told she exclaimed, “Oh! I thought it was an old coffee table. The one I saw was polished and shining and used for that.” The wooden lasts had no connection with shoes in her mind.

The bootjack near by was something to throw at the cat. This bootjack was home made of a small piece of board – about a foot long, five or six inches wide with a V cut in one end and a three inch block nailed to the under side. An old leather boot stood near with a pair of copper toed shoes beside it. In this same exhibit were buttoned and laced shoes of a time when today’s models were called slippers. The boot jack was used for “jacking off” the boots which usually came off hard.

Again, what’s that? This time it was an old long-handled bed warmer, with a still older and more common soap-stone and a little charcoal warmer, used to keep the feet warm on long sleigh rides. With today’s hot water bottles, electric pads and blankets, such things are not necessary. I used to take a hot brick (warmed in the oven) wrapped in a cloth to warm my bed on cold winter nights. There was also a foot-muff which was used in the sleigh and sometimes taken into the church when sermons were long and heat lacking. Overshoes were unknown years ago.

In these days of electric lights and flashlights it’s quite a curiosity to see some of the old lanterns and lamps that the earlier people used. When we look at the exquisite sewing and quilting done by candle light we wonder how it could possibly have been done.

Not many people wore glasses in those days and some of the old “spectacles” in the museums today are “wonders to behold.”

The first lanterns were made of tin with holes for the light from the candle to shine out through. A collection of old lanterns is most interesting.

The next exhibit was of the dairy industry, showing the development of the churn from its beginning as a dish and a spoon up through the stone crock with a wooden top through which a wooden “dasher” was worked up and down by hand, to the barrel type which could be operated by a dog or sheep in a treadmill.

The various containers which were used to contain the milk while the cream was rising, showed the earthen and tin pans and buckets and an early “separator.” The old strainers and the strainer pails are surely unusual in this present time. The old butter bowls and ladles were made of wood and used for washing the milk out of the butter and working the salt into it. If the salt wasn’t well worked into the butter, it would be of an uneven color.

There were many kinds of molds used before the standard brick shaped mold came into use.

Large dairies had a large “butter worker” that mixed the salt into the butter by a roller worked by a crank. Then the butter was packed into wooden tubs or stone crocks.

One thing they did not have in the dairy exhibit was the cloth strainer which was used before the metal ones were invented, It consisted of a length of “cheese” cloth and was held against the pail on both sides as the pail was tipped to pour the milk into the pan or dish.

“What’s that?” “That” happened to be an old “stab” corn planter in the farm department. In its day it was considered a great invention as a man would plant a hill of corn as fast as he could walk instead of digging a hole with a hoe, counting out five kernels of corn from a canvas bag tied around his waist, then covering the corn with his hoe before moving on to the next hill.

The spinning wheels came next. It was hard to realize that once upon a time all cloth was made at home. The wool and the flax wheels weren’t alike and it was easy to see why. But the same loom was used for both wool and linen. In this exhibit were the different tools used in the preparation of cloth – the distaff, hetchel, cards (not made of paper but of wood and steel) swifts and reels. Each had its special purpose.

The things in the kitchen section were really intriguing and one remarked that the women in the early nineteenth century must have had a strong right arm and back. So many of the articles were made of iron – tea kettles, roasters, pancake griddles, “spiders,” and kettles of all sizes and shapes.

No one wanted to go back to the range that their grandmothers used nor the ice box.

The laundry was equally interesting and each declared that “the good old days” of that era had no enticement of them to give up their “automatics” and decided that grandma didn’t have life so easy after all.

First came the farmer who planted and harvested the wheat and sent it to be ground into flour.

In older days the grain was ground in small grist mills by a local miller. The amount of wheat taken to the mill was called “a grist,” and was often taken, a bagful at a time, on horseback, and the mill was operated by water power.

Next came the mother who made the flour into bread by a very different process from the commercial bakeries of today.

The people of Bible times had only unleaven bread which was really flour, water and oil mixed together and was more like our crackers or the old-time “hardtack” of army days.

Yeast as we know it today was of the later century. Even in the beginning of the twentieth century it was a homemade product. First a potato was grated and a little sugar and water were added and allowed to ferment. Most housewives saved a little of this mixture each baking day to add to the new yeast (leaven) as a “starter.” It was generally kept in a tightly closed bottle or can in a cool place until needed. Sometimes the “starter” was borrowed from a neighbor.

“Baking day” came regularly every week. Just as Monday was wash day, Tuesday was for ironing, so also Friday or Saturday was baking day so as to have bread, cake, pies and cookies fresh for Sunday.

The bread had to be “set” the night before so it would have time to rise and be ready for the “tins” and could be baked while the usual housework was being “got out of the way” so as to leave time for the other baking. The process of starting the bread was called “setting the sponge” and it was usually kept warm either by being wrapped in a blanket or set on a chair near the stove.

In the morning when the dough had risen to the height satisfactory to the housewife it was turned out onto a well-floured “dough-board” and given a thorough kneading and then put back for another period of rising.

When risen enough, it was again turned out onto the dough board, cut into even portions, kneaded lightly, and shaped into loaves to fit the bread tins and again put to rise. Quite often one portion was cut into small bits and shaped into biscuits so warm bread could be had for supper without cutting the fresh loaves.

When risen again, usually a little above the top rim of the tins, it was put into the oven and baked about an hour.

Someone who disliked the first mixing of the “sponge” invented a “bread mixer” into which all the ingredients were placed and mixed by turning a crank on the top of the pail. This also did away with the second kneading, and only when the dough was ready to be shaped into loaves was it necessary to use the dough-board.

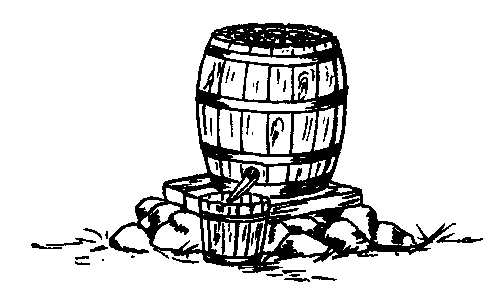

There were no five-pound sacks of flour in those long-ago days. Most flour came in barrels holding one hundred and ninety-six pounds. One could buy a half-barrel sack but most merchants preferred to deal in barrels because of the mice that chewed holes in the sacks.

I can think of no nicer “homey” smell or sight than some homemade bread fresh from the oven.

STOVES

When you press the button to your electric stove or turn on the gas, to the gas range, do you ever think how our ancestors prepared and cooked their food?

Everyone knows that the Indians and many of the early people used open fires for heat and cooking though many people ate everything raw, if it were eatable in that state.

Fireplaces were soon installed in many homes and with the invention of “cranes” and the “brick oven,” cooking was easier.

The fireplace crane was a movable iron attached to the inside of the fireplace in such a way that an iron kettle could be hung on it, suspended over the fire in such a way as to make the cooking fast or slow.

After the fireplaces came the stoves. These were rather crude – not much like the ranges that came during the beginning of the present century.

My grandmother’s stove – inherited from her mother-in-law was a “high oven” one, the only one I ever saw.

It had four griddles and the oven was at the back instead of under the griddles as in later models.

The front legs were only about a foot high so the griddles were only about two feet and a half from the floor; so no wonder that grandma and great-grandma were humped back.

The oven was at a convenient height so one could look in at what was baking without stooping. Grandfather put blocks under the stove legs so as to make it easier for Grandma to stir whatever she was cooking on the top of the stove.

The fuel was wood and a well-filled woodshed was the sign of a provident householder.

Grandfather had a good supply of wood every autumn but it became badly depleted by early summer when heat was not so necessary. As summer advanced the fuel supply grew less and less until one day when he came in at noon and asked “Is dinner ready?” “It’s all on the table” was grandmother’s reply. And if was but in its raw state as there had been nothing which could be used for fire.

He never went into the field after that without first providing that dinner would be “on the table” in an eatable condition when noon came.

My mother’s stove had only four griddles and one of them was always occupied by an iron tea-kettle as it was our only supply of hot water, except the boiler on wash day.

How wonderful it seemed when we had a new “range” with a “reservoir” and a “warming closet.”

The “parlor stove,” replacing the fireplace was a welcome invention as the “stove pipe” furnished extra heat for at least one bedroom upstairs.

This stove was quite simple and not very large at first but became larger and more ornate as the use of iron became easier.

The “box” stove was one of the earlier styles as it could be easier to keep filled with wood and took larger “chunks.”

In one schoolhouse where I taught there was a box stove which took a two foot length of wood and had a “griddle” on top which could be lifted up so the fire could be “poked” and wood added instead of putting it in through the door.

One of the larger boys was always called upon when more wood was needed as the teacher was seldom strong enough to handle the “chunks.”

As time passed the “parlor stove” became larger and more elaborate. Sometimes it was taller than a man and trimmed with steel and with many panes of isinglass in the doors.

As coal became more plentiful both ranges and parlor stoves were made for its use. This was a great convenience as fire could be kept over night so the house would be warm in the morning.

The first electric stoves resembled my grandmother’s “high over” stove only the griddles were higher up.

SHOPPING

I “went shopping” today. The old expression used to be, I “went to the store.”

I thought of the little boy who told his father that he could do something that his father couldn’t do at his age. When asked what that was, he replied, “I can carry home twenty dollars worth of groceries and you couldn’t.” How True!

When I first “went to the store,” I carried a slip of paper which I handed to the “storekeeper” and he did the collecting of articles and brought them to the counter while I just watched and looked around.

As a child, the store was a fascinating place to me. I got such a thrill standing by the candy show case looking at the tempting array of “stick candy,” gum drops and other varieties which a penny would buy.

Then there were the beautiful “bolts” of cloth, calicoes, now called percales, ginghams and outing flannels. More expensive materials were not in stock in local stores.

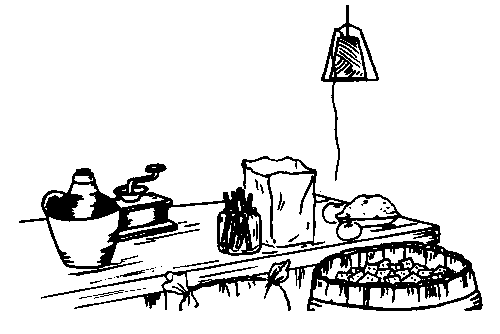

Along the other side of the store were the groceries with their tempting smells. Barrels of sugar, both white and brown, molasses, crackers, oatmeal and flour. A barrel of flour weighed 196 lbs., and a barrel of white sugar was 250 lbs.

What would anyone do with a “barrel” of flour or sugar now? When I was first married, at the beginning of this century, we bought a barrel of flour, a hundred pound bag of sugar, ten pounds of oatmeal (now it’s called oat flakes) and other groceries in proportion as we lived seven miles from the store and had no car, so whenever we went “shopping” we had to spend most of a day.

We’d take our extra eggs and butter to exchange for our groceries. Butter brought us 25¢ a pound during the winter and less in the summer. Eggs were as low as 15¢ a dozen during the summer but higher when cold weather came, as few farmers were equipped for winter production of both butter and eggs.

Sometimes we’d kill a veal for which we’d get maybe as much as ten cents a pound and the liver wasn’t counted so we usually kept that for ourselves. A fat dressed hog would bring five to eight cents a pound. There was no refrigeration then, as now, so the storekeeper had to buy fresh meat from the local farmers.

Have you ever heard the expression “as slow as molasses in January?” We bought our molasses by the quart or gallon and had to take our own container, called “the molasses jug” which the clerk filled from the barrel and during the cold season, it was a low job.

Very few groceries were packaged so most had to be weighed or measured so this took considerable time.

Sanitation as we know it today was unheard of at that time. The merchant did try to keep covers over most of the barrels, and of course the cheese had a glass cover. Some stores carry the old fashion kind of cheese, and it’s spoken of today as “store cheese” to distinguish it from the packaged cheese that we get at the supermarket.

The coffee came “in the bean” in hundred pound sacks and was ground by the merchant in a large “coffee mill” if one didn’t have her own mill at home. Both mills now are antiques and quite a curiosity to the present generations, tho I believe some supermarkets have an electric grinder one can operate oneself if they select a variety of coffee that comes in the bean. Instant coffee was unknown until about thirty years ago.

There were no adding machines or trade stamps in those days. The merchant had to do the adding up of the items. If he were in a hurry and he trusted the customer, he might pass the bill over for him to add. If the bill were fairly large, he might hand over a small bag of “hard” candy for the children or a cigar if the man was a smoker. The men did most of the trading in the old days, especially the farmers, as they’d “go to the store” whenever they had some other business in town.

COMPARISONS

I was speaking with a friend this morning about another friend and she remarked, “She must be tougher than a boiled owl.” I never heard of anyone eating an owl, boiled or cooked in any way, so who would know how tough it would be.

“As quiet as a mouse,” and everyone knows how very quiet a mouse can be.

As “poor as a church mouse” is generally used in speaking of person’s physical condition as there isn’t supposed to be even a crumb in a church to put flesh on one.

As “poor as Job’s turkey” is supposed to refer to one’s financial condition, though I can’t see why.

“As homely as a hedge fence,” and “as pretty as a picture” refer to a person’s face, though I’ve seen hedge fences that were quite attractive, and pictures that I wouldn’t hang in my house.

“As crooked as a rail fence,” and “so crooked that he couldn’t sleep in a roundhouse” are not considered complimentary to one’s character.

“As black as a crow,” and “it shines like a nigger’s heel” are degrees of color.

“Each old crow thinks her own is the blackest” is the remark often heard when a mother resents a comment made about her child or children, conveying the idea that hers are better than others.

“Bigger than all outdoors” is used in reference to anything that has any dimensions of a great size.

“Like a scared cat” is mostly used in connection with speed. “He ran like a scared cat” is a common remark but cats can run fast even when not frightened.

After mention of the cat, we must not forget the dog. “His bark is worse than his bite,” and “They fight like cats and dogs.” Sometimes a dog and a cat are the best of friends and fight for each other. It’s only when they are strangers that they fight – unlike humans who always try to put on a good appearance before strangers and fight with their friends.

“Like a wet blanket” We all know this feeling when some of our choice suggestions are met with opposition from the ones we felt sure would not “let us down.”

“As stubborn as a mule” is an expression that we are all familiar with and none of us like to have it applied to us. We’re just strong-willed instead of stubborn.

“As crazy as a loon.” Loons are queer water birds and have the name of being crazy because of the noise they make which sounds like an insane person’s laughter.

“As mad as a hornet.” This needs no comment.

“Fit as a daisy,” and “fit as a fiddle” are used in many ways and with many different meanings.

We’ve heard the expression many times, “I’m as hungry as a bear,” and “I could eat a raw dog.” One certainly must be hungry to use either expression. “As dry as a bone” also comes in to express a physical condition, but is oftener used regarding a book, a party, or an entertainment.

“As high as a kite” is generally used in reference to a person who has celebrated not wisely but too well. Also we hear “As drunk as a lord.”

It “stinks like a pole cat,” and “as sweet as a rose” are opposite comparisons.

“Happy as a lark,” “bright as a dollar,” and “smart as a cricket” are all complimentary.

“As slippery as an eel” is not considered complimentary to a person’s character.

“As odd as Dick’s hatband.” I can’t imagine what that band could have been like as men used to be very conservative in all their apparel.

“As old as Adam” denotes great age, also “As old as Mathular” and “as old as the hills.”

“As cool as a cucumber,” and “as cold as ice” are degrees of coldness in a person’s aspect regarding events.

“As mad as a wet hen.” Hens don’t like water except to drink, so many years ago when a hen became broody and insisted on setting, the farmer’s wife would dip her into a tub of cold water. This usually changed her mind.

“As white as a sheet,” but sheets aren’t always white now, even though they aren’t “battleship gray” as they were sometimes when not properly washed.

APPLES

There have been many changes and improvements in apples, their preservation and treatments in my life time.

My first apples were those that grew on my grandfather’s farm and we thought they were “the best ever” although now I know they were just wild fruit and grew on scraggly old unkept trees. “Old Grease” was the favorite because it was such a good keeper.

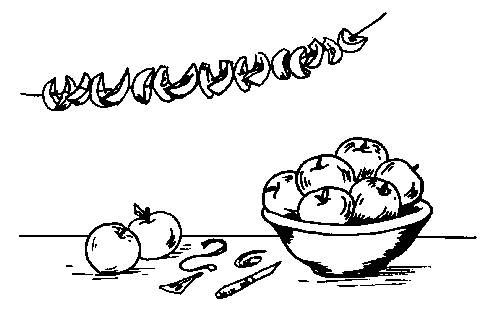

Once when we were visiting at Grandfather’s they had an “apple bee.” We little ones were allowed to help by washing the apples while the older ones pealed, quartered, cored and strung the quarters on long strands of twine, each step being done on an assembly-line plan although such a plan had not received recognition at that time.

The string was cut about two yards long so when the ends were tied together they would reach from one overlay to the next as the kitchen had no ceiling except the floor of the chamber above. Nails were driven into the overlays above the stove and the apple strings hung on them. Sanitation was unknown in those days and although the apples were nice roosting places for flies it didn’t seem to affect the taste of the dried apples, although one uncle used to say, “Tread on my toes and tell me lies, but don’t feed me dried apple pies.”

After a few years an apple peeler was invented and that made it easier and quicker. I can remember trying to peel an apple without breaking the strand and then swinging it three times around my head and letting it fall behind me as it was claimed at it would give me the initials of my future sweetheart. This was also a Halloween stunt.

When I was about fourteen my father gave me the fruit from a certain tree for drying and that was my Christmas money. He made a rack about three feet square and covered it with screen, and that hung over the stove in the kitchen so I didn’t have to string the apples. By then we became more sanitary and the rack was covered with cloth or paper to keep the flies off and hasten the drying. The quarters were sliced so they dried more quickly.

Dried apple pies were made similar to the fresh ones as the apples were soaked over night and sometimes cooked before being used. Dried apple sauce was a treat too.

This is my favorite cake recipe even now.

Two

cups of dried apples cut fine and soaked over night in one cup of

water. Then add one cup of molasses and cook until tender. One cup of

sour

cream, or one cup of butter and one cup of sour milk. One cup of sugar,

one of

raisins and three of flour. Season with one teaspoon each of cinnamon,

cloves,

nutmeg, and lemon extract and two teaspoons of soda.

A VISIT AT GRANDPA’S

One afternoon when I was about six years old, my father took us – my mother, brother and little sister, to visit my grandparents who lived in Wilmington, between twenty and thirty miles from our home in Lake Placid.

There were no cars in those days so a horse and buckboard was our mode of travel.

My brother rode on a small box between my parents’ knees and the dashboard. I sat between my parents and my little sister sat in my mother’s lap.

It was then as now, a lovely drive down through “the Notch.” We stopped for a few minutes at “The Notch House” to visit friends. This house has long since disappeared with the building of the hard surfaced road.

Grandfather’s farm was Northeast of Wilmington village and on a cross road so when we were nearly to the turn off, my brother and I took the old school path across the cow pasture and reached the house before the others as we ran most of the way. The house was a one-room log cabin with a built on summer kitchen which could be used only in summer as one had to go out doors to get to it.

The main room was kitchen, living-room and bedroom for most of the year. There was a “trundle” bed which rolled under the big bed and the older children slept in the loft. Visitors, and when the married children came home, were sent down to Great-grandma’s to sleep. Great-grandma had the largest log house I ever have seen. It had a back entry from which the stairs went up to the loft, a pantry and two fair-sized bedrooms at the back and the front half consisted of two good-sized rooms.

It always seemed queer to me that Great-grandma should have such a big house for just herself and that Grandpa should live in such a small one with his big family but now I know. It was her home.

Great-grandma’s bed was in the kitchen and I can’t remember ever being in the other front room until after she died and I “helped” Grandpa and Grandma move from the little house into the bigger one. I was then about six years old. Great-grandma had a loom which was at the foot of her bed near the window. She sat on the foot of the bed when weaving. I remember seeing a piece of her weaving on the loom. It was yellow and blue check wool from which grandma would make shirts for Grandpa and the boys. It was also used for blankets and petticoats.

One time when I visited at Grandpa’s, I watched the men shear the sheep and then I helped grandma wash the wool and “pick” it. Picking the wool was done before it was carded because washing it matted it so it was hard to card. Carding was often done at home before carding mills were near enough so the fleeces could be taken to them.

There was a little brook back of the two houses and I almost always fell in sometime during my visit.

Grandma had a “wash place” near the brook where she did the family “wash” from early spring until fall, as it saved bringing the water up to the house. A large iron kettle was placed on three even sized stones and filled with water, then a fire was built under it and when the water was hot it was tipped into a wash tub and the kettle refilled so the clothes could be boiled after being rubbed on a rub-board.

Grandma’s lye barrel was also there and the big kettle was used for making soft soap.

More than eighty years later, I visited the “old place.” Grandpa’s little house is gone, the “play house pines” are no more, having been sold for lumber years ago, the barns are gone but Great-grandma’s house is still standing – four square – and used as a summer home. The brook has a dam across it so there is little pond now near Grandma’s “wash place.” There were no commercial dyes in those days so Grandma used what she could find. Gray was one of the easiest colors as there was almost ways a black sheep in the flock and this gave a nice gray yarn which was used mostly for the knitted socks. If she needed more she saved the tea leaves for several days and then boiled them in an iron pot strained out the leaves, returned the fluid to the kettle and added a spoonful of copperas to “set” the color. Blue was obtained by dissolving indigo in “chamber lye” (urine). One of the family produced the best “lye” for this dye.

Butternut shells or bark were steeped for brown and onion peelings and copperas gave the yellow which Great-grandma used her weaving. Copperas and indigo could be bought at the local store. Salt was used with some dyes to set the color. I loved to watch Grandma spin the wool into yarn. Think of the miles the spinner traveled back and forth as she drew the rolls into yarn. Grandma was luckier than most women as she had a “lazy man” wheel. She could sit and as she turned the big wheel, the head swung away twisting the roll into yarn and after a certain distance it came back so she could add another roll. When the head was full the yarn was taken off onto “swifts.” From the swifts the yarn was taken off generally two strands together and made into balls which were later twisted together on the spinning wheel and taken from that onto a reel. Twenty times around on the reel made a skein.

If Grandma’s kitchen stove were in existence today it would sell, as an antique, for enough money to buy the latest in gas or electric. It was what was called “a high oven stove.” The fire box and griddles were only about two feet above instead of under the griddles. Grandma had to stoop to stir anything cooking, but the oven door could be opened easily as the top of it was shoulder high. Grandpa put blocks of wood under the legs to raise it up about ten inches to make it easier for Grandma. There wasn’t any reservoir and she kept an iron tea-kettle on one of the back griddles.

The summer before I was fourteen, my father, brother, and I went “over the mountain” from Lewis to Grandpa’s to get my sister who had spent the summer there. When we were nearly to the top of the mountain we found the way blocked by a skid-way of logs across the road. How to get by? We were too many miles on our way to turn back. There had been no sign telling that the road was blocked. I never saw my father so mad. Finally he unhitched the horse and led her around through the brush. My brother and I pushed on the buggy while Father pulled and at last we got the wagon up and over the logs. No one was at home when we got there but we didn’t mind. Father went in and had a nap and my brother and I went exploring. They were at a Sunday School picnic and were surprised when they found us waiting for them.

I sincerely regret that my grandchildren will never have the memories of their visits to their grandparents that I have of mine.

AN

OLD-TIME TEACHER

The state law required that a teacher be eighteen before a certificate could be issued so I didn’t begin my first term of school until the last day of October.

Perhaps I was lucky to get a school at that late date but all the other older teachers had signed their contracts earlier in the summer and no one wanted this isolated school. The trustee felt that he was fortunate to get even a beginner and was willing to wait.

In signing that contract I nearly signed my life away as it took several years to regain my health.

First, my boarding place was at the trustees and I paid a dollar and a half a week for my board and room, out of the sum of five dollars and seventy-five cents wages.

The board was farmers’ fare and “plenty of it such as it was.” The room was the parlor bedroom and supposed to be the best in the house, but it was COLD. There was no heat between it and the living room and the parlor door was kept closed, so it was like going outdoors when I went to bed. I couldn’t take a glass of water with me as it would have frozen.

It was over a mile to school but in one way I was fortunate. Two of the pupils lived beyond so if their father carried them to school he’d take me too, otherwise I had to walk.

We all had to “take our dinners” as there were no cafeterias in those good old days and it was over a mile to anyone’s home.

The school house had been built many years before and at that time there were over forty pupils. Now there were seven, two girls and five boys.

At the time of building the school there was a thriving community having a large charcoal industry that supplied the forges at Au Sable Forks, Black Brook, and Keeseville.

The school house was beside quite a large brook so it wasn’t far for the children to go for a pail of water.

One side of the plastered wall was covered with the names and addresses of the teachers who had preceded me in the days gone by.

Heat was furnished by a large box stove near the center of the room and we burned seven cords of wood that term as we filled the stove at night so the room would be warm for the next morning. A cord of wood measured four feet high, four feet wide, and was eight feet in length. That stove took a two-foot length of wood.

The desks were hand-made of one-inch boards and were large enough for two pupils.

The equipment consisted of a desk and chair for the teacher, two quite large black-boards, one chart for the beginners, several maps, a water pail and dipper, and a box of chalk for the black-boards. The erasers were handmade, a piece of wood with a piece sheepskin nailed on.

I taught “reading, ‘riting, and ‘rifmetic,” also English, spelling, geography, history and physiology. I didn’t need the “hickory stick.”

Slates were used exclusively as pens, pencils, and paper were hard to get.

The only social life I had during those four months was a “spelling bee” in the next district in which I was fortunate to “spell down” all the others. I could go home only once a month because of the distance.

It was during this term of school that I met Essex County’s most famous thief and jail-breaker. He was in hiding at the time and this was a good place to hide. I met him again that spring at Teachers’ Institute while a number of teachers were “going through the jail.” He was more delighted to see me than I was to see him, especially in that place.

My next school was larger and nearer home and paid six dollars a week.

School hours in those days were from nine until four with an hour off between twelve and one and two fifteen-minute recesses. Through the winter months the lamps would be lighted by the time the children reached home. There were no lights in the school so very little studying could be done towards the end of the afternoon session. I used to take half an hour off the noon period so as to excuse school at three-thirty.

There were no grades then. Each child worked independently. Maybe he could do fifth grade work in one subject and third or fourth or even sixth in some others.

Many of the pupils in those old-time schools became teachers, and good ones too, without first “going away to school.”

Friday afternoons were “specials” as school was always dismissed half an hour early and usually the last hour was something different from the usual program. Some afternoons there would be a spell down or an arithmetic match, or maybe reading from a favorite book that was being read in the opening exercises in the morning as an incentive to promptness.

Whoever saw a teacher wearing an apron in the school room? We used to, either a black sateen or a white cambric one, and they were serviceable too, protecting our dresses from chalk dust and dust.

My little great-granddaughter said to me not long ago, “Grandma, I don’t like boy teachers.”

The present generation is lacking in imagination and initiation. Everything is planned and supervised for them. When they are left alone they are bored and can only think of mischief and destruction. At least that is the public opinion for that is what the radio and the newspapers tell us.

Maybe we wouldn’t have riots and sabotage and looting if they weren’t played up so much to the public.

At recess at school as a child we used to play “Hide-and-seek” which is still played by children everywhere but “Drop the handkerchief, Ring around the rosy, and London Bridge” have passed into oblivion. In winter we played “Fox and Geese.” A large circle was made with paths towards the center which was the fox’s den from which he ran to catch a goose around the ring. When caught, he became the fox. “Duck on the rock” and “Sheep, run, sheep” were also favorites. Hide the thimble was an indoor game. There were no ball games as is played today but we had “One old cat” and “Two old cat” played by three or four with a flat piece of board and a soft ball – often home-made – made from old yarn and string and covered with coarse cloth.

“One old cat” was played by three, a pitcher, a catcher and a batter. When the batter struck the ball he ran to the extra base and back before one of the other players could get the ball and get to home base before he did. Then he became the pitcher and the pitcher became the catcher and the catcher came to bat. “Two old cat” was similar only the batters faced each other so that the pitcher and catcher were both pitcher and catcher as the ball was thrown both ways.

Jolly old winter has pleasures for me, skating and sliding in innocent glee. Winter certainly was a time of enjoyment. Nearly everyone had a sled, skipper or double runner and as soon as there was any snow everybody went sliding. Some of the sleds were home-made and a skipper was certainly within the reach of every boy who could drive a nail, find a barrel stave, a stick of wood, and short length of board. Sometimes two staves were nailed together. Great fun was the result of sliding on a shovel, in a pan, an old discarded butter bowl – the forerunner of the flying saucer of today.

Skis were unknown in my young days but sometimes we tried sliding standing up on two barrel staves. Toboggans were quite plentiful and were lots of fun especially if there was a crust.

We don’t have crusts very often now but years ago they were quite frequent as the weather was different then. A crust was formed by a warm spell in the weather with a little rain and then turning cold. Once there was a crust so thick that a horse could walk on it and not break through, and it was as slippery as ice.

A double runner was two sleds connected by a long board or plank and would carry from two to five or six persons and it was considered more fun to slide on a double runner than for each to slide alone. They were sometimes called “bobs.” Their only fault was that they were heavy and it took two or three to haul them back up the hill.

Skating parties were also great fun. Then there were the church suppers which were called “Sociables” as supper wasn’t served until ten o’clock or even later. While the older people visited, the young ones played kissing games such as “the needles eye,” “post office,” musical chairs, and several others that I can’t member now.

Occasionally there would be a dance but no one would think of dancing at a sociable as they were church affairs. And such suppers for only a quarter. Sometimes they had an oyster supper.

Sometimes we had game parties when checkers, dominoes or flinch was played. Once there was a top party. Each one was supposed to bring a top made from a thread spool and the game was to see whose top would spin the longest.

Then we often had molasses candy pulls and sometimes in the spring there would be a maple sugar party at the sugar house of some farmer where wax on snow was the treat.

At least once during the winter the whole school put on an entertainment. These consisted of recitations, dialogues, tabloids, drills, and songs. We had no organ or piano in that little old district one-room school, but someone could play the mouth organ for the drills and songs and as the pupils were of all grades and ages, there was no lack of actors.

Sometimes we’d have a spelling bee. Two leaders were appointed by the teacher and they would select contestants from the audience until all were chosen who wished to participate and then the teacher would pronounce the words, each side alternating. If one missed, the word went to the other side. The one who stood the longest was the champion.

This was followed by a social evening, dancing, playing games, or just visiting. I can’t remember that we ever served refreshments at these gatherings at the school house and seldom at the house parties unless it was a birthday celebration.

There were the quilting bees and many others whenever the occasion arose or a necessity presented itself.

Farmers used to gather to help each other and the wives went along to help prepare the dinner, especially if it were a threshing, a barn raising, or if a sick neighbor needed help to prepare the winter’s supply of wood or finish some needed job.

Quilting bees were popular for no young girl could get married until she had an adequate supply of quilts in her hope chest. One wonders at the fine stitches in these old quilts when one thinks that the supply of light provided by the small windows and the candles would be a good reason now-a-days for not doing any sewing.

“Singing schools” were another form of entertainment. When I was about twelve years old, my brother and I attended one of these. An old man by the name of Samuel Ober was the singing master and our book was “The Key Letter.”

I

never learned to sing but my brother did. I think we were the

youngest in the class and some of those who attended were nearly as old

as Mr.

Ober. It closed with a concert and everyone seemed to enjoy it.

BEAUTY

CULTURE

The desire for personal beauty and adornment is as old as creation. Adam and Eve were the first to wish for it but they had little need for it.

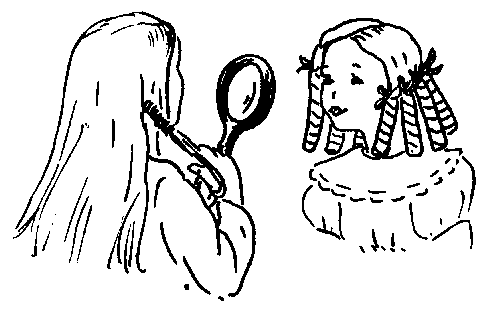

The “beauty parlors” of today are of the present century. In fact our mothers were their own “beauticians” as “permanents” were unknown until the last few decades.

The child born with naturally curly hair was indeed fortunate. “Rag curls” were the usual form as “curlers” were invented in the beginning of this century.

“Crimps” were produced by dampening the hair and braiding tightly until thoroughly dried. You may have seen an old daguerreotype or photograph of a girl with long crimped hair and wondered at its crimps.

We were more careful then about appearing, before even our families, with our hair in “curlers.”

There was general rejoicing when someone invented a “curling iron,” which could be heated in a lamp chimney and curls made without having to sleep in curlers which were anything but soft. One had to be careful that the iron didn’t get too hot and singe the hair.

Then came the “Marcelle wave” and also an iron for making it but this was a little harder to do so “specialists” began to advertise and thus the modern “beauty salons” came into existence.

GUM

Gum! Where is the child who does not know that word and what it means? There’s Tuty-Fruity, Spearmint, Bubble and the first and least known by the present generation, Spruce.

Not many of the present generation and few of their parents know the pleasure of chewing genuine spruce gum and some would look at you in horror if you offered them a piece but to me it’s “tops,” the only kind that gives any pleasure.

My father was a “gummer” and that was one source of his income. As a young man he was a guide and he knew the location many spruce forests, so when he was not employed he spent days gathering gum. This is a discharge from the cracks in the bark similar to pine pitch but this hardens into lumps of various sizes.

His gathering “spud” was cone shaped with a sharp projection on the upper edge, and mounted on a ten-foot pole so at he could reach the gum higher than he could reach otherwise. The lower deposits were often chipped off with a pocket knife.

During the long winter evenings he would clean each lump, going over it carefully to chip off any dark spot or piece of bark. The cleaned gum was sold mostly during the summer to the “city people” who came to Lake Placid.

One winter Father thought he would try an experiment so he saved the cleanings and put them into a cheese-cloth bag which he hung in Mother’s steam cooker with a basin under it to catch the gum as it melted and dripped through the cloth. The clarified gum as made into rolls just before it cooled, similar to our molasses candy. It was delicious but lost its lasting quality, which was what the children liked as we couldn’t have a new chew of gum every time we thought of it like the children of today.

Gum was precious and was saved carefully from one chewing until the next, and horror of horrors, was often loaned to another. Sanitation didn’t bother us then so much.

I remember my first “boughten” gum. It was pink paraffin, flavored with wintergreen and shaped like a whistle. It was good but the after-effects weren’t, for it seemed to produce a terrible sore throat.

There was a saw-mill not far from our home and during the winter season when the logs were being brought in, the yard was alive with children looking for gum as, to many of them, this was their only source of supply for the year.

SHOES

“Cobbler, Cobbler mend my shoe, Get it done by half past two.”

This is a children’s old rhyme taken, I think, from an old Mother Goose book.

Shoes today are not much like the ones worn by the pioneers nor is the making of them like even those our grandparents had.

Sandals were the first shoes and they were not much different from the ones of today.

Sometimes we see an old cobbler’s bench glorified into a present day coffee table, which is a long way from the original use.

In early times a cobbler made shoes and boots from leather which he had tanned himself or it had been prepared by the head of the household, for which the shoes were to be made. The members of a family were all outfitted with shoes or boots at the same time, and repairs were made to the old ones while the cobbler was available as he often travelled from one family to another at certain times each year.

Most people planned on having two pairs of shoes, one pair for common wear and the second for Sunday or special occasions and these were kept and worn for years.

The “every-day” pair was usually quite heavy and serviceable as they were worn indoors and out, in rain or slush or snow as there were no rubbers or overshoes in those days.

Along with the cobblers bench, he had sharp knives for cutting the leather, awls for making holes for the waxed thread which he used for sewing the seams as he didn’t use needle with the thread but a pointed end that was stiffened by extra wax.

The awls were also used for making holes in the sole-leather for the wooden pegs which he used to fasten the soles to the uppers.

The pegs were nearly an inch long and were in cards similar to the first matches and had to be cut apart. If the pegs went through into the inside of the shoe, they were smoothed off by a rasp which was an iron like a file only a great deal coarser.

The waxed thread used for sewing the boots and shoes was made of linen and several strands were twisted together and waxed with bees wax.

One seldom sees leather boots now but in the “good old days” they were very popular among the men, from farmer to city dweller and how very proud was the little boy when he was given his first pair of boots, especially if they had copper toes.

When boots were worn, a “boot jack” was a necessity. This was often home made and consisted of a board about a foot long and four inches wide with a V cut in one end and a three inch block wood under the notched end. One placed one foot on the board and the other heel in the notch and pulled the foot out of the boot.

DENTISTS

Five year old Johnnie went to the dentist for the first time.

This was the first of many visits that he will make to the dentist in all the years that are to be his life’s span.

Dentistry, like all other professions, has changed during the century.

When I was a child there were no dentists like there are today and whenever a tooth became loose one of the parents tied a string around it and pulled it out with a jerk if it were a front tooth. If it were a molar, someone found a pair of pliers and did the best he could to extract it. Baby teeth were never given any care whatever. I was in my teens before I ever had a toothbrush.

The stout man of the neighborhood usually acted as a friend in need whenever anyone was suffering from toothache as he most always had a pair of pinchers or pliers and the strength to pull the tooth as that was considered the only remedy for an aching tooth.

The first dentist I ever knew was a Dr. McKenzie who lived in Ausable Forks and came to Lake Placid about twice a year.

I never knew of his filling a tooth. His chief business was pulling and making plates.

Dr. McKenzie generally stayed with my parents and when my father died at the age of eighty-three, he was still wearing the upper plate that Dr. McKenzie made for him nearly fifty years before.

The thing I remember best about him is the little black pot that he used to cook the plates in as he’d walk back and forth before the stove watching it all the time and we children didn’t dare go near him or the stove because he told us it would blow us up if we did. I suppose there must have been a pressure gauge which he was watching. He gave my sister and me our first rings.

My next contact with a dentist was when I was nearly sixteen.

Dr. Henry Knapp of Essex came to the Lewis Hotel and I went to have a cavity in one of my front teeth filled. He cleaned it out with little instruments that looked like crochet hooks – all done by hand – no drills like the dentists use today. The filling was still there when the tooth was finally extracted more than forty years later.

My next dentist was Dr. Holt of Westport. He came to the Maplewood Inn in Elizabethtown twice a year for a week or two, according to the amount of business. He had a chair which could be raised or lowered according to the need and he had a drill which was operated by the pressure of his foot, and a larger number of instruments than Dr. Knapp. He was very sympathetic and could show you how sorry he was by shedding tears for you at the least sign you made of being hurt. He also had a variety of fillers as Dr. Knapp had only silver.

One thing still seems to be the same and that is that a fairy will come and leave some money under the pillow if the tooth is placed there for safe keeping until the fairy can come for it.

REMEDIES

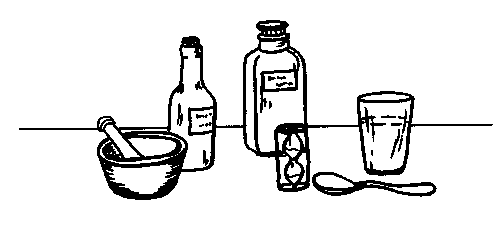

When I was a child in the 1880’s a doctor was hard to get and many “home” remedies were known and used.

Our doctor lived eight miles away and someone had to ride or drive a horse that eight miles to notify him that he was needed and the patient had to wait that length of time plus the time needed for the doctor to reach him.

Maybe that is why we were called “patients” – because we needed that virtue (patience) when we were ill.

My father wanted to be a doctor but in his youth such an education as was needed for that profession was out of his reach, he contented himself by being “a friend in time of need” and learned as many “home remedies” as he could from whatever source was available.

Many elderly women were gifted in “healing the sick” and as midwives, and were always ready and willing to help in times of birth and death.

One of my first memories of remedies was the one most commonly used for sore throat for that was my most frequent ailment. “Whistlewood” (striped maple) bark tea for gargle.

Every autumn someone was sent to the woods to bring back some of the young sprouts of the striped maple and the bark was stripped off and dried and stored away for use during the winter. Whenever one of us developed a sore throat, some of the bark was “steeped” and the resulting tea was used as a gargle. It was surely effective.

One of the remedies I hated was “sweet flag tea” for tummy ache. Sweet flag roots were gathered, cleaned and dried and when needed the roots were grated on a nutmeg grater until about a teaspoonful was obtained and then about half a cupful of boiling water was poured over it and a little sugar added and when cooled a little it was drank and generally did the trick. Peppermint tea is only a little more palatable to me.

Catnip and sage teas were used whenever a cold started to develop.

If pneumonia started the chest was rubbed with lard and camphor or lard and turpentine and covered with a flannel cloth. In later years an infusion was made by steeping wormwood leaves in hot lard and applied warm to the chest. I was in my teens before hot lemonade was known as a remedy for a cold. No one ever thought of “going to bed” as a remedy – nor of a cold being contagious.

No one ever thought of “taking stitches” in a cut or wound. The first move was to stop the bleeding and this was often done by the use of a “puffball” now known as a beefsteak mushroom. We used to watch for them in early fall and save them until needed. A nutmeg worn around the neck on a string was a “sure” preventative and cure of that painful eye affliction known as “a sty.”

An old sock or stocking was a sure cure for sore throat if wound around the neck at bedtime, especially if it had been worn a day or two. No credit was given to any gargle the next morning. It was the stocking that cured. Salt and water and a little vinegar was a gargle that anyone could mix and use.

Nosebleed was quite common and had various cures. Ice applied to the back of the neck or a cold silver knife laid on the spine was often used. A small roll of paper held between the upper lip and the gums was sometimes used. A red wool piece of yarn worn around the neck was often believed to be a preventive.

Sulphur and molasses was a spring tonic and all of us children had to take it to cleanse our blood and pep us up.

A bit of soda (saleratus) the size of a bean in a little water was the accepted remedy for heartburn or indigestion.

A little gunpowder moistened with a few drops of vinegar was often used to cure ring worms. Later when iodine was obtainable that was used to stop its spreading by painting the outer edge. It sure was a heroic remedy. It was claimed that a deep impression around it made by a thimble or other suitable object would stop its spreading.

Salves were often home made as drug stores were unknown or very far away. Grandma used to make a “balm-of-Gillilad” salve but I don’t know the ingredients except that she used the buds from that tree and always made it in the spring.

One remedy for a sore that had been infected was made from a few shavings from a bar of laundry soap, about the same amount of sugar (brown sugar was the best) and a little sweet cream, all worked together into a salve. This I know is good as it healed a sore of long standing for me and it was prescribed by a doctor.

Every home had a bottle of Castor Oil. This was the universal remedy for constipation. It was also used for corns.

Most all of the local stores carried quite a selection of “remedies.” There were several “tonics.” “Burdock’s Bitters” was one of the most popular especially with the men as it contained quite an amount of alcohol. There were “plasters” for lame back and back aches. “Pills” were abundant for various ailments.

OLD

WIVES’ WHIMS

I’m not superstitious and not many people are but so many “whims” seem to bear out the ideas expressed that one often has cause to wonder.

So many people wouldn’t think of sitting at a table of thirteen because of the whim that if one did, one of the thirteen would surely die before a year had passed. A broken mirror brings seven years of bad luck tho I can’t say why. It’s bad luck to spill salt. If you do, you must throw some over your left shoulder to keep misfortune away.

If a baby sleeps during the day and keeps awake at night, fussing and keeping its parents awake, a sure cure for this condition is to change the baby from head to foot in the crib. This is claimed to be a positive remedy and easy to use.

Some claim that a left-handed child should be made to use the right hand or he will always have an inferiority complex. Others claim just the opposite. Take your choice.

You mustn’t look at the new moon over your left shoulder. I don’t know why.

If a dog howls there’s sure to be a death in the near future in the community. When you hear of a death there’s sure to be three close together. If one forgets something when leaving the house and decides to return for it, he must sit down and count to ten before starting out again. This is supposed to break the spell.

“Bind your garters around your feet and set your shoes to face the street.” This rhyme was composed years ago when a lady’s garter was a narrow knitted strip which was wound around the leg several times and the end tucked under. This was supposed to have the effect of keeping the feet in good condition. Also always dressing the left foot first was considered necessary. A stitch in time saves nine. This is more a truth than a whim so most people are willing to admit.

“Beaus don’t go where cobwebs grow.” The older housewives are most often excellent housekeepers and no cobwebs were allowed. They didn’t have the distractions of the younger generation nor electric aids.

As Monday begins, so goes all the week. This hasn’t proved true for me. Company on Monday, company all the week. False. To everyone’s delight.

In selecting the wedding day this jingle was used. “Monday health, Tuesday for wealth, Wednesday the best day of all. Thursday for losses, Friday for crosses and Saturday no luck at all.” This was observed before Saturday became the favorite day that it is now. Some couples dared to tempt fate.

You must not cut your fingernails on Sunday. If you do, the devil will find some job for your hands during the week. A baby’s fingernails mustn’t be cut for if you do you’ll make him light fingered. One of the most ridiculous is, if you sew on Sunday, you’ll have to rip it out with your nose on Monday.

Whims are not all a woman’s prerogative. I knew a man who, for years, had carried a small potato in his pocket until it had become flat and as hard as a stone. Why? As a sure cure and preventative of rheumatism.

Speaking of cures and preventatives, there’s the one of wearing a piece of red wool yarn around the neck as a preventative of nose bleed and wearing a nutmeg on a string to prevent styes on the eyes.

Dropping your dish cloth is a sure sign of company but it will be someone who isn’t as good a housekeeper as you are. That’s a comforting prospect for most of us.

You mustn’t give anything sharp as a wedding present as it will cut the marriage vows and cause the marriage to break up. Also a sharp gift between friends cuts the friendship.

When walking with a friend you must never let anything come between you. You must never go one on each side of a tree or a person.

Some people will never undertake a new job on Friday because of the saying, “Soon done or never done.”

You must plant the garden seeds, especially the ones producing vines, in the dark of the moon if you don’t there will be lots of leaves and little fruit. My father always said that he planted his seeds in the earth and not in the moon and he always had lots of produce.

You mustn’t touch a toad or you’ll get warts. A sure cure for warts is to steal someone’s dish cloth, rub it on the warts and bury it. When it rots the warts will be gone. The seventh son of a seventh son touched my warts with a bit of spittle and they disappeared. Another cure for warts is to rub corn or oats on them and feed it to the hens. Sometimes they just disappear without any “old wives cure” being used.

If bubbles form on the top of your cup of tea or coffee, you must skim them off and swallow them quickly so they’ll bring you money.

Another money sign is if your right hand itches, you mustn’t scratch it but put it into your pocket. Women always had pockets in their dresses years ago. If a tiny spider appears near you, you must catch it and put it into your pocket if you want it to bring you money.

Some people consider it bad luck to kill any spider because of the tradition that it was a spider who saved the life of the Christ child on his flight into Egypt, by spinning a web across the mouth of the cave in which the Holy Family were hiding. The searchers knew that he wasn’t in there because he would have brushed down the web when entering.

See a pin and let it lay, you will cry before the day. See a pin and pick it up and you’ll surely have good luck. I knew an old woman who said she’d never bought but one “paper of pins” during her married life and she was considered “well to do” among her neighbors, so there must be some truth in this saying. She picked up every pin she saw, no matter where it lay. It’s bad luck to watch a departing guest out of sight.

“An apple a day keeps the doctor away. An onion a day keeps everyone away.”

“A lazy girl’s wheel runs the best when the sun’s in the West.” In early times every girl was taught to spin and given a “stint” (a certain amount) that she must do every day. So if she neglected to do it in the early part of the day she had to hurry to get it done before sunset.

SANITATION,

GARBAGE AND POLLUTION

Sanitation, garbage and pollution are new words in the vocabulary of the older generation.

Today each one in a family has his own towel, comb, drinking glass and other things which are considered personal. Years ago one comb answered the needs of the whole family and was kept in a “comb case” (usually of tin) under the family mirror (looking glass) in the kitchen.

There was only one towel, usually of the “roller” kind and everyone used it for hands and face. If the family were large it was changed twice or three times a week.

As the laundry was done by hand on a “rub board” it was necessary to make it as small as possible for the mother or the “hired girl” of the house if the family were fortunate enough to be able to afford extra help with the housework.

As for the drinking glass, a tin dipper was usually kept in the water pail and everyone drank from it whenever thirsty. There was also one kept near the pump or at the brook side where the water hole was.

There was no chlorinated water in those days and a brook, a well, or a cistern supplied the family water even in quite large villages.

If the cistern “went dry” it was filled from the nearest river or lake. The village teamster usually did it by draining the water in barrels which he filled with a pail.

There were no garbage trucks or disposal units for there really was no need for them. Each family used every scrap of food as the children were taught the maxim of “a clean plate.”

If there were any scraps left that the family couldn’t or wouldn’t eat they were given to the cat, the dog, or to the chickens. No canned cat and dog food in those days.