| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2005 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2005 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to |

Sister

Mary

Felicitas, R.S.M.

Republished

by

Kellscraft Studio

2005

Originally

printed by the

Museum of Pok-O-Moonshine

I

was born in 1880

so have lived through the “good old days” which are

my memories now. A

friend

said to me a few years ago, “Why don’t you record

these things. Your

generation

will soon be gone and there will be no one who remembers,” so

that is

how my

memories came into existence.

Leila

M. Wells

Essex,

New York

October,

1969

TRAVELLING

One

lovely

afternoon in February, I enjoyed a fifty mile trip to Lake Placid to

visit my

granddaughter. It took about an hour in one of the new automobiles.

As

I journeyed I

thought of the difference in travel from my grandmothers’ day

to the

present

time.

It

would have

taken my grandparents more days for the trip than the hours which it

took me.

When

grandmother

went to town or to visit a neighbor she went on a farm wagon drawn by a

yoke of

oxen. There was a long board placed on the front and rear axles, a

chain was

fastened to the axles for her feet to rest upon and a rope was strung

from

stakes for her back and for her to hang onto so she wouldn’t

lose her

balance

and fall. Sometimes they used the wagon box with a chair in it or it

had straw

for her to sit on. This was used if they were “going to the

store.”

Grandmother

didn’t go shopping every week like her granddaughter does.

How

proud the

family was when a horse was brought home hitched to a

“democrat” wagon.

This

wagon had no springs and a short reach between the axles so was not

much easier

riding than the farm wagon but the horse was faster than the oxen so it

shortened the time on the road.

After

the

“democrat” came the “buck

board.” So called because the “reach” was

longer and

gave some spring to the seat, especially if the occupants were heavy

people

like both my grandparents.

Later

came the

carriage. This was quite elegant as it had a “top”

that would fold down

and

especially if it had hard rubber tires. Then there was the buggy. I

don’t know

why it was so called. Then the family wagon with two or three seats and

a

canopy top called a surrey.

I

mustn’t forget

to mention the stagecoach or “tally ho” which was

enclosed with doors

on either

side with space and seats on top for six or eight passengers or for

baggage.

It

was wonderful

for us children to watch the “tally ho” go by with

the horses on the

run and

the horn blowing. This was the way they entered the main Street of Lake

Placid

in the 1880’s. Sometimes there were four horses hitched to

the

stagecoach.

It

has been most

interesting to watch the improvements in the automobile from the

beginning of

the century to the present day.

The

change in our

highways has been as great as the change from the ox wagon to the

present

automobile.

When

my father was

a boy his father was commissioned to survey and build a road past the

Cascade

Lakes, which would shorten the route between Keene and Lake Placid.

As

a child I

remember riding over that road when it was so narrow that teams

couldn’t pass

each other only at the “turning put” places. Now it

is a two lane

highway.

Most

of the roads

now are hard surface. The owners of the first automobiles had to leave

them in

the barn after the first snow fall and until the mud was dried up in

the

spring. There were no snow plows then nor sanders.

After

heavy snow

falls, the farmers would hitch their teams to their heavy sleighs and

fasten a

board to one side of the back sled and plow the roads themselves.

Sometimes if

the roads were badly drifted they’d take down a portion of

the fence

and drive

through the fields around the drifted portion of the road. Those were

“the good

old days.”

WOOL

(By

Mrs. Thomas

J.

Wells) Leila M. Wells

Did

you ever hear

someone say, “You must be wool gathering?”

Everyone

knows

that wool comes from sheep, and raising and caring for sheep is the

oldest

occupation of man. Cloth made from wool is the oldest fabric.

The

sheep of today

is so different from the sheep of Bible time as to be almost a

different animal

except that its coat is still wool. Even in the years of my remembering

there

have been improvements in the size of sheep and in the grade of wool.

Shepherds

watched

their flocks by night lest even one little lamb should go astray.

The

sheep’s wool

grows during most of the year and gets long and thick during the cold

weather,

but when it gets warm the wool loosens from the skin and is easily

pulled loose

and comes away, otherwise the poor animal would be very uncomfortable

as the

summer gets warmer.

Now-a-days

the

wool is clipped off with electric shears, rolled into bundles and sold

to

dealers. Years and years ago the early shepherds had no shears with

which to

clip their flocks so each sheep was plucked or picked as its wool

loosened.

Those who didn’t own sheep used to go around the pastures

gathering the

wool

from the bushes where it had been pulled out as the sheep went through,

wandering from one place to another and thus came the expression

“wool

gathering.”

As

a child I

remember when grandfather “sheared the sheep.” It

was a warm day the

later part

of May. Each sheep was caught and held while a man with a pair of

“sheep

shears” (similar to our present day grass shears) started in

on the

front legs

and cut the wool off close to the skin all over the sheep and how bare

and

funny it looked when let run. Often the poor little lambs

didn’t know

their own

mothers.

Grandfather

sold

most of the wool but always kept several fleeces for family use. He

always kept

at least one black sheep whose fleece made gray yarn that

didn’t have

to be dyed

and Grandmother used that for socks for her men folks.

After

the

“shearing” the women took care of the wool that

wasn’t sold. First it

had to be

washed, then dried, and I’ve spent hours helping

“pick” it as it was

always

matted together after the washing. Grandfather then took it to the

“carding”

mill where it was made into “rolls” for spinning. Sometimes

Grandmother carded it herself into ‘batts” to be

used

as filler for new quilts.

Her

spinning wheel

was different from any other I ever saw as she could sit down and the

“head”

swung out and back instead of being stationary like the other spinning

wheels

where the spinner had to walk up and back.

The

first yarn was

spun very fine and generally two strands were twisted together for

knitting

socks and stockings and mittens. Only one strand was used in weaving

cloth.

“Great-grandma” had a loom in her kitchen and I

remember seeing her

weave

material for Grandfather’s shirts. It was even check, yellow

(“copperas”) and

blue. Later the loom was used for weaving rag carpets and rugs.

SCHOOL DAYS

A

big yellow

school bus has just gone by my house having left about a dozen boys and

girls

on the corner near by. Not one of them will walk but a short distance.

School

is so

different from my school days. I wonder if the children ever think how

school

might have been in their grandparents’ days.

When

I began going

to school back in the 1880’s I had to walk at least one and a

half

miles to the

“old red school house” where all grades (grades

were unknown then) were

taught

and as I was one of the little ones, I was left mostly to myself. No

“busy

work” or anything interesting to do.

The

teacher

believed in the “hickory stick” method and maybe he

had to as some of

the

pupils were as tall as he. I was as afraid of him as I was of the

travelling

bears that came to our village every summer.

After

a year or

two in that school, a teacher named Mrs. Mary Stickney opened a

“select” school

in the top story of a boat house and the parents paid a set price for

each child.

She

was a good

teacher and I began to like school and to learn. Her only fault, as I

decided

later, was that she had favorites — her two daughters and my

younger

sister.

She

was a

beautiful penman and we had regular writing lessons in home-made

writing books

with copies written by her. “Every line and every letter, try

to write

a little

better” was one.

My

next school was

a new one room one built across the road from my home so I

didn’t have

to walk

very far. It was taught by a William Barker who later became a Baptist

minister

and was stationed at Elizabethtown for several years.

My

schools until I

became a teacher, were mostly one room district ones and even as a

teacher I

had the one room schools and taught all the grades.

Grades

were

originated after I began teaching. Before that a pupil could be doing

5th grade

arithmetic and 8th grade reading and history. Social studies was

unheard of.

One

of my teachers

was an old man who had once been a school superintendent and his

hobbies were

arithmetic and “grammar” (English). If he finished

the regular schedule

a

little before four o’clock (the usual closing time) he would

say,

“Let’s add a

little bit,” and put a column of figures on the blackboard.

Diagramming

was the

next favorite and I’ve seen sentences from our 5th grade

reader that

covered

half the blackboard space. Diagramming is a lost art now.

At

recess and noon

we played games. “One old Cat” was a game for

three, “two old cats”

took four.

This was a ball game. The smaller children played “Drop the

handkerchief” or

“Ring around the rosie.”

How

would today’s

children like to be in school from 9 until 4 with no electric lights or

any of

today’s “necessities” and have to walk to

school?

WINTER

SPORTS

“Jolly

old winter

has pleasures for me.” Each season has its special joys and

pleasures.

Just as

I could hardly wait in the spring for a certain apple tree to blossom,

so I

could go barefoot, so it seemed that snow and ice would never come so

that I

could skate and slide down hill.

I

loved to slide

and I’ve slid on about everything except skiis, which were

not in

existence in

my sliding days. A barrel stave was the nearest to a ski in my

childhood.

Tho

“babysitters”

were unknown when I was small, I remember several times when a relative

was

available that my parents went tobogganning with other young people. We

were

living in Lake Placid then and the sliding parties were held on

Steven’s Hill.

From the top of the hill the toboggans would go nearly to the opposite

side of

Mirror Lake.

The

summer before

I was seven, my sister and I saved our pennies and when winter came we

bought a

sled. It had a little girl painted on the blue top so we called it

Marjorie

Daw. We were still sliding on it years later whenever there was a crust

and we

were home from our schools, over the weekends. We’d get up

early in the

morning

and go out for about an hour of fun. Each took a sled but I usually

took the

toboggan. Once in a while one of my sisters would feel brave enough to

take a

slide with me. Our “bobs” were two sleds held

together by a long plank.

Sometimes the sleds were owned by two different boys and the plank was

removable. It was a long way from the “bobs” used

on the Olympic runs,

as ours

had no brakes and no steering gear, except the rope and the

steerer’s

feet. The

ride down the hill was fun but the hike back with the heavy bobs was

not so

funny. Each slider was supposed to lend a hand during the return.

It’s

too bad that

cameras were so rare in those days as pictures of our loaded bobs would

be very

interesting now, as we didn’t have the sports clothes that

are the

“must” of

today. There were no rails for our feet so each had to hold the feet of

the one

behind him on the plank except for the steerer, so no one really wanted

to be

second on the plank as he was responsible for his own feet as well as

those of

the one behind him.

The

nearest thing

to the present “Flying Saucer” was an old wooden

butter bowl. These

butter

bowls are not available now as what few are still around in some

antique shop

and priced sky-high. I never had slid in a Flying Saucer but in an old

bowl one

goes round and round until the bottom of the hill is reached and then

one has

to sit for a while until his head clears. A tin pan was sometimes used

as a

substitute for the bowl. An old shovel of any kind gives one a thrill.

After

the toboggan I think I enjoyed the “skipper” next

best. What’s a

skipper? It

was made from a barrel stave, a block of wood about a foot high and a

small

piece of board for the seat. One needed to have perfect balance to make

a

successful descent, but it was thrilling, at least I found it so.

We

used to have

skipper races to see whose skipper went the fastest, as nearly everyone

had one

and some boys had several. Sometimes two staves were fastened together

and some

of the skippers were fastened together. Sometimes two staves were

fastened

together and some of the skippers were made of four staves, two on top

and two

on the bottom and these didn’t need the block of wood and the

board.

These were

used more like a toboggan, but only one could slide on it at a time.

Our

dog, Dixie,

loved to go sliding with us, but we didn’t enjoy her company

so much,

as she’d

grab us by the cap or sleeve and drag us off the sled, as she seemed to

fear we

would get hurt.

Father

thought we

shouldn’t learn to skate until we were ten years old but I

cheated. My

brother

was older than I so when he was tired of skating, he’d let me

take his

skates.

There was a small depression in our lawn and each winter we lugged

water to

fill it and make a place to skate. Here we learned to avoid disaster by

all of

us going in the same direction. As we entered our teens we were allowed

to

attend skating parties on the village mill pond. Generally a bonfire

was built

on the shore and when tired of skating, we’d gather round it

and sing

the

popular songs.

CHARCOAL

Charcoal!

What

thoughts come to your mind at the mention of this word? Delicious

steaks and

barbecues? Neat little blocks in a paper sack bought at the store?

To

me the word

brings memories of my grandfather and “the boys”

(my two oldest uncles)

and my

father, all of them grimmy and smelling strongly of smoke.

It

wasn’t until I

was in my early twenties that I learned more about it and what

“burning

charcoal” really meant. I was teaching in a country district

where that

was one

of the sources of income and was invited to spend a Saturday in the

woods

watching the process.

There

were no

chain saws then so the cutting of the trees was done mostly with an ax

and a

bucksaw, or a cross-cut saw was used to cut the trees into four-foot

lengths.

When

the trees had

been made ready, the men started “making the pit.”

I never could learn

why it

was called a pit for the pieces were stood on end, four or five at

first and

then a row of sticks around them and more rows around until the base

was about

fifteen or eighteen feet across. Then another tier was built in the

same way on

top of the first. When this was finished it was covered with evergreen

branches

and then about a foot of dirt was packed on until the whole looked like

an

Eskimo’s igloo. A small opening was left in the top for the

smoke to

come out

and small openings at different places at the bottom where the fire was

started. This had to be watched constantly so that it would burn slowly

and not

go up in a glorious bonfire. If a blaze started, more dirt was put on.

It took

several days of slow burning and Constant watching for the wood to

reach the

right stage for “drawing.” Drawing consisted of

first closing all

drafts and

the slow dying of the fire, then the uncovering and raking which had to

be done

slowly so as not to start the fire in case a spark was left.

Finally

the

charcoal was bagged in burlap bags and drawn in farm-wagons to market.

At

that time

charcoal was used in summer hotels and blacksmiths’ forges

but in my

first

memories it was used in iron smelters and forges.

Grandfather’s

charcoal was

drawn by ox team to the iron works at Black Brook. Father used to time

our

visits to “Grandpa’s” so as to be there

to help him when he needed more

than

“the boys,” which was generally during the burning

when someone had to

watch

day and night.

Charcoal-burning

used the timber that now goes into pulp wood. The tops and limbs too

small for

charcoal sticks are used for fire wood. The peculiar odor of the smoke

is

always associated with my grandfather’s home.

CORN

“When

the swallows

come to the barns it’s time to plant the corn.”

Planting

corn has

changed since I was a little girl on the farm, like all farm operations.

There

were no

riding implements in those days and the farmer walked miles each day as

he

guided the plow and then “dragged” the field to

prepare it for planting.

When

the field was

considered ready for planting it was cross-marked by two men who

carried a long

pole with three or four chains attached, three feet apart, dragging so

as to

mark the place for the hills. Some farmers had an idea that the marker

could be

drawn by a horse so one man could do the marking. This marking was

necessary as

an aid to the cultivation of the growing corn.

After

the field

was marked both ways, it was ready for the planting which was done on

Saturday

if possible so the children could help — one child to each

adult.

The

man would dig

a hole with a hoe and the child would drop the kernels into it and then

dirt

was hoed over it and generally given a pat with the hoe or was stepped

on to

firm the soil over the corn.

Five

kernels were

the usual number put into each hill.

|

“One

for the

cut-worm, One for the crow, One for the woodchuck And two to grow.” |

And

as soon as a child

could count to five he was considered old enough to help. He carried

the corn

in a small pail. If no child were available, the man had a canvas pouch

tied

around his waist and counted out the kernels with his left hand while

using the

hoe with his right.

Before

a horse

drawn cultivator was invented, the weeds were cut down with a hoe,

several

times through the growing season.

When

the corn had

ripened it was cut by hand with a tool called a “corn

cutter,” laid in

bundles

and tied either with withes of twisted grass or binder’s

twine. Then

set up

several bundles together in “stooks.”

When

twine was

used it was cut into the right length for tying, and carried, generally

by

being drawn through the suspenders (an unknown article today when belts

are the

main support of a man’s trousers) of the binder.

The

stooks were

left in the fields for several weeks to dry out. When dried they were

brought

into the barn for husking out the ears of corn. Sometimes if the

weather was

good the husking was done in the field.

A

“huskingpin” was

used for the easier opening of the husks. This was generally a pencil

shaped

piece of wood a little less than an inch in diameter and six inches in

length

with a leather loop in the middle which slipped over the middle finger

to hold

it in place whenever the hand was opened.

Often

a “husking

bee” was held if the farmer had a large barn and lots of corn

to be

husked.

This was an occasion for a “frolic” and the girls

joined in the work

and the

fun and sometimes there was competitions to see which couple could husk

the

most corn.

A

red ear earned a

kiss for the husker.

New

cider and

doughnuts were the refreshments.

The

Indians grew

corn (maise) before the Englishmen came to America and taught them how

to grow

and use it.

Hominy,

grits,

samp, and corn meal are all corn products.

“Hulled”

corn used

to be a great treat. Lye obtained from wood ashes used for soaking the

corn

until the hull and eye could be rubbed off easily and then the corn was

washed

in several waters until no hulls and eyes remained. This corn was

similar to

today’s hominy or samp.

My

mother used to

make a large amount of this each winter and kept it frozen in a crock

in an

outside room, bringing in whatever she thought was needed for a meal.

Sometimes

it was served with milk and sugar as a cereal. Popcorn has always been

as

popular as it is now although we never had it in such variety.

Nearly

every home

had a “corn popper.” This was a rectangular wire

box with a tin lid on

a long

wooden handle. If not one of these as substitute a

“Spider” or kettle

was used.

When a spider or kettle was used it was possible to put butter and salt

into

the corn as it popped.

A

small family

sized popper was invented after electricity became used more generally.

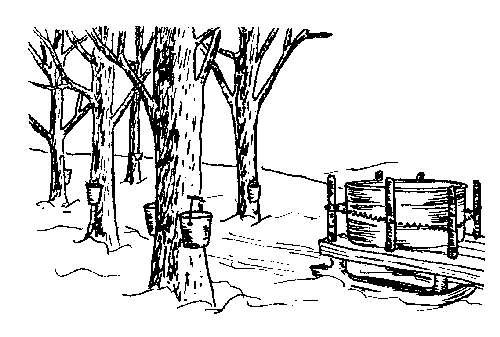

SUGARING

(By

Mrs. Thomas

J.

Wells) Leila M. Wells

Did

you ever eat

maple sugar, maple fudge or syrup? And did you ever wonder where such

delicious

flavor was found? It’s truly American.

The

Indians were

the discoverers of this deliciousness and taught it to the early

settlers of

New England and New York. How did they discover it? Thereby hangs a

tale. The

story goes, so I’ve been told, that some Indians were on a

hunting trip

and cut

a maple tree for their camp fire and noticed the drip of what they

thought was

water from a cut in the tree, and, as water wasn’t too

plentiful, they

placed

one of their dishes under it and caught quite a little. Some brave

tasted it

and found how sweet it was and when they used some of it for cooking

they

discovered that it became sweeter so when they returned home they tried

boiling

it and discovered syrup. I don’t know if they or the Pilgrims

were the

real

discoverers of the final process that produced the sugar but it

probably was

accidental also. Perhaps some housewife neglected to take the syrup off

the

fire at the right time and it “sugared off” as the

expression goes.

There

have been

many improvements in the process of maple sugar making even since my

earliest

memories of it. At first the sap was boiled in a large brass or iron

kettle out

of doors and was “finished off” in a smaller one in

the house as syrup

or

sugar.

One

of my earliest

memories is of the time my mother, my brother and I went into the sugar

bush to

spend the night. At that time sugaring had advanced to the stage where

it was

no longer just a family means of obtaining sweetening for pies and

cakes and

apple sauce.

“Sugaring

off” was

an occasion for a party. The boiled-down syrup was poured on the snow

to cool

and the “wax” was the most delicious thing ever

tasted. That was the

way the

maker knew when the right stage for sugar was reached. “Soft

sugar” was

poured

into tubs to be used later. “Hard sugar” was put

into tins or molds and

sold to

the “city people” during the summer.

My

father had a

large “sugar orchard,” as it’s now

called, several miles from home so

he had a

“shanty” where he boiled the sap in a large pan

instead of a kettle and

had a

bunk where he could sleep when he didn’t have to feed the

fire or add

more sap

to the pan.

Sugaring

generally

started in March and continued for five or six weeks or until the leaf

buds

started to grow. During the early part of March preparations started by

getting

the buckets and spouts ready. Now-a-days these are purchased but at

that time

they were hand made. The spouts were made from sumac branches about an

inch in

diameter and cut six inches long. One end was whittled down to fit a

three-quarter inch hole. About half way of the stick, a sawing was made

to the

center of the stick and that half was split off. A wire was used to

push the

pith out. When the spout was driven into a hole in the tree the sap

would come

through and drop into a bucket placed underneath.

The

buckets were

hand-made of wooden staves. I’ve watched my father make them,

and years

later I

visited the same sugar bush and saw the buckets and sap yoke that he

had made.

Gathering

sap was

different then from now, when it is done with a large tank on a sled

drawn by

horses. Then it was done by men emptying the smaller buckets into two

larger

ones which were carried on a yoke across the shoulders. When the large

buckets

were full, they were carried to the shanty where they were emptied into

storage

barrels and the man went back for more. Sometimes he had to carry his

load

quite a distance, so he walked miles through the snow and slush as sap

runs

only when the temperature is above freezing.

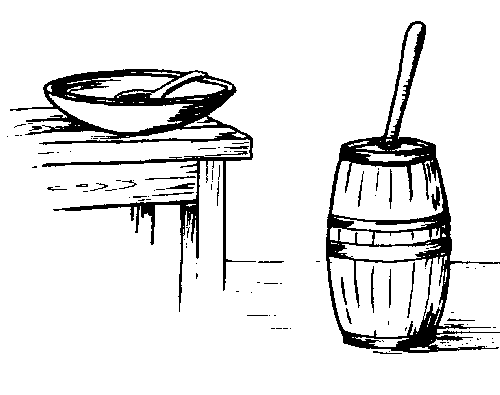

BUTTER

Leila

M. Wells

When

you put

butter on your bread or toast, do you ever think what it is, where it

comes

from and how it is made?

Butter

comes from

cream, cream comes from

milk and milk comes from a cow. A farmer cares for the cow, feeds her

and milks

her but now-a-day, he does not make the butter as in the days long past.

Years

ago nearly

every family owned a cow even though they had very little land. The cow

was

pastured generally in a community lot and either milked at the pasture

bars or

brought to the home barn.

The

milk was

strained through “cheese cloth” into shallow pans

and set on shelves,

either in

the pantry or cellar for the cream to rise. After about twenty-four or

thirty-six hours the cream was skimmed off with a tin skimmer. This was

an

instrument with holes in it so the milk would run through as the cream

would be

too thick to go through.

When

enough cream

had been accumulated it was put into an earthen jar called a

“churn”.

The cover

had a hole in it so the “dash” handle could come

through and be worked

up and

down, keeping the cream in motion until the butter formed in small

particles.

These particles were skimmed out into a butter bowl (a large wooden

bowl) and

water added to wash out whatever milk was left in. Generally two

different

waters were used and a ladle was used to agitate the butter particles

and wash

out the milk. Then the salt was added, about an ounce of salt to a

pound of

butter, and thoroughly worked in so that the butter wouldn’t

be

streaked.

Then

it was made

into balls for the table or packed in earthen jars or wooden tubs for

market.

A

childhood treat

was when my grandmother would put a pan of sour or

“labbard” milk in

front of

me and sprinkle it with brown sugar. “Delicious” in

my estimation.

Making

butter was

our chief source of income when we were first married.

We

had a small

“separator” so we didn’t use pans and we

had one of the new churns a

barrel set

in a frame and turned end to end by a hand crank.

We

had regular

customers and packed the butter in earthen jars, holding from five to

ten

pounds and if we received over twenty-five cents a pound we thought it

wonderful.

Butter

now comes

from large factories, wrapped in waxed paper in one pound packages and

tastes

like money.

In

olden times if

the butter was slow in breaking, a fire poker was heated red hot and

thrust

into the churn to “burn the intch.” This raised the

temperature of the

cream

which was just what was needed. Cold cream was slow to turn into butter.

In

olden times

when the butter in winter didn’t have the bright color of

June, the

butter-maker used the juice of grated carrots for coloring. Later

a coloring was obtainable at the

village store.

FENCES

“Don’t

fence me

in” are the words in an old song, so fences have existed for

ages and

there are

many kinds for many uses.

The

early settlers

used what was available such as stumps, rails and stones.

The

stump fences

that remain today are really quite unique and pretty.

That

was one way

that the early pioneers could make use of what was on hand and what

today is

destroyed was then used. They served two purposes, cleared the land and

fenced

it at the same time.

As

so many of the

farms were stony, the stone fences or walls as they were called, also

served

these two purposes. Many of them have disappeared now as they have been

used

for house and barn foundations and as sub-bases for many of the new

roads.

Rail

fences came

next and they were of two kinds, those laid zig-zag and those laid

straight

with their ends through holes in a larger rail driven into the ground.

These

fences took up less room than the zig-zag ones and it was easier to

keep the

fence row clean of briars and brush.

Then

came the

barbed wire fences and later still the woven wire ones.

Ornamental

fences

were used in villages and around lawns and gardens.

Some

of the fancy

iron work fences are still found and the white picket fences are being

built

now-a-days more as a decoration than for a practical use.

Most

farmers are

doing away with the old types of fences and are using the one strand of

wire

which carries electricity and one contact with the fence is sufficient

to teach

the animals to avoid it.

WASHING

I’ve

just returned

home from the laundromat and I couldn’t help thinking how it

would seem

to do

my laundry the way my grandmother did hers or even as my mother did.

I

remember

watching my grandmother do her washing one summer day when I was seven

or eight

years old.

First

my uncle

filled a large iron kettle from the brook near the “wash

place” which

was a

little way from the back of the house, near the brook and under some

trees.

The

kettle was set

on three or four large stones and a fire was built under it. When the

water was

hot, some of it was put into a large wooden “wash

tub” which set on a

bench

near by. Into this Grandma put the sheets and pillow slips after adding

a

generous amount of soft soap and then she put in the “rub

board” and

proceeded

to give each article a good rubbing.

After

each article

was rubbed it was dropped into the big kettle and boiled.

After

each article

had been rubbed and boiled it was rinsed in several waters from the

brook and

spread on the grass to dry. The colored clothing was not boiled but was

rubbed

extra and spread on the bushes to dry.

Mother’s

washings

were similar only her wash water was heated on the kitchen stove in a

“boiler.”

This was a tin or copper, oblong vessel with a cover And she had a

“pound

barrel” and “pounder.” The barrel was

hard wood and the clothes were

pounded

with an article similar to the old dasher of a churn until someone

invented a

pounder with a spring. Some “pounders” were blocks

of wood about six

inches

across and ten inches high, fastened to an old broom stick.

The

first washing

machines were open tubs with a corrugated lining and a semi-circle rub

board

and was hand operated. Only a few articles could be washed at a time in

them.

The closed tubs came soon after and were still hand operated. Then

someone

invented one that could be operated by a dog or goat in a tread mill

attached

to the wheel of the machine by a leather band.

Grandma

wrung her

clothes by hand but Mother had a wringer which was a great help, both

in time

and strain on the clothes.

There

used to be

considerable competition to see which woman would get her clothes on

the line

first on Monday morning. And if you didn’t wash on Monday you

were

considered a

poor housekeeper. One woman remarked that she couldn’t wash

or iron and

be a

Christian all in one day.

The

ironing was

done with flat-irons heated on the kitchen stove and usually consisted

of a set

of three — two heated while one was used. A collection of old

flat

irons, as

they were called, makes an interesting exhibit at any antique show.

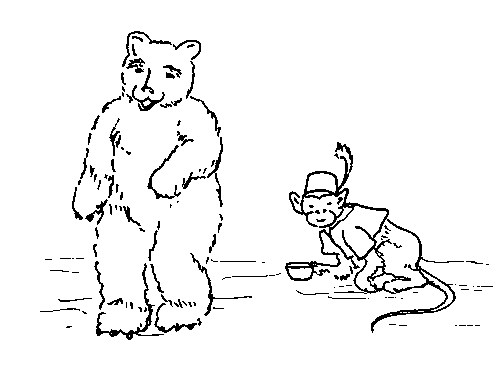

BEARS

AND MONKEYS

When

I was a child

the coming of the bear was looked forward to with both fear and

anticipation.

When

the word

spread that the bear was coming I generally ran for the house but

curiosity

soon overcame my fear and I joined the other children on the side of

the road.

Generally

there

were two men, dirty and unkept, with the bear which was black or brown

(cinnamon) lead by a chain fastened to the collar. One man lead the

bear and

the other man followed with a prod with a sharp point.

When

a crowd had

gathered the bear was made to dance while one of the men sang

“Tarry-ta-roon,

ta roon ta ray” over and over.

Then

the men would

shout “Twenty-five cents to see the bear climb the telephone

pole.”

Someone was

always willing to part with the hard earned quarter.

The

men and bear

usually spent the night in some farmer’s barn.

The

last

travelling bear that I remember seeing appeared one morning just as

breakfast

was being served at the now vanished Hunter’s Home in New

Russia. Not

one of

the boarders or help missed the sight. This was the summer of 1906.

Another

event

which occurred each summer but was looked for with great anticipation

was the

coming of the organ grinder hand organ man and his little monkey, Jocko.

Jocko

wore a

little red jacket and did so many amusing things that the organ grinder

usually

resembled “The Pied Piper of Hamlin,” as he went

along the street.

The

children

nearly emptied their “piggy banks” to put money

into Jocko’s little tin

cup.

Whenever he received a few pennies he’d climb onto the

man’s shoulder

and empty

them into the man’s hand.

The

organ was an

oblong box which the man carried on a strap around his neck. It had a

crank on

the right side which he turned to produce the music and a movable leg

which was

let down to help hold the organ while the crank was being turned. Oh!

The joys

and pleasures of childhood.