|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

VESPA'S FOOD SUPPLY

WHILE in the spring and early summer Vespa lives largely upon nectar, she is not at all conservative upon the food question. All is fish that comes to her net. She is decidedly omnivorous, even enjoying cooked food when she can get it. She often flies into dining-rooms and kitchens and helps herself to what she finds; an informal assumption of unoffered hospitality that gives her more pleasure than any one else concerned.

Later in the season she sucks other people's fruit juice with the same optimistic disregard of property rights, and with her sharp jaws cheerfully punctures and then eats the choicest spot on the juiciest, ripest, and best fruit that the orchard affords.

The best is none too good for a wasp, she believes, and lives up to her faith.

The fruit-grower thinks otherwise and looks with eyes of wrath upon the white-and-black, or yellow-and-black imps that ruin his best fruit and sting him if he presumes to interfere.

Sometimes the wasps eat all the pulp from a specially attractive fruit, though too often their epicurean tastes are content only with the best of a pear or an apple, taking out enough to spoil it and leaving the rest. Almost every one has had the experience of picking up what looked like a perfect pear or apple and finding it a mere shell filled with wasps. Such an apple was once given a shake, when out through the single hole that gave entrance to the interior came a tail wildly brandishing a sting, ready for business. After the tail came the rest of the wasp, who, once fairly out, flew about her affairs without molesting the hand that held the apple. After this successful exit came another tail brandishing a fiery dart, and after this another and another, until a dozen or more wasps had sallied forth tail first in a triumphant, touch-me-if-you-dare procession.

Since the cause of their disturbance was out of sight the clever wasps, fearing to come out head first and thus put themselves at disadvantage to a possible foe, preferred the exercise of military tactics that though simple were sufficient.

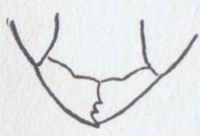

Vespa requires strong jaws, for with them she

does most of the hard work of a wasp's life, from cutting up solid food to

chewing wood fibre into paper pulp for nest-building purposes. ; And they are

strong, large, toothed and horny in substance, joined to the sides of the head

below the eyes, and, as is usual in insects, working sideways.

Vespa requires strong jaws, for with them she

does most of the hard work of a wasp's life, from cutting up solid food to

chewing wood fibre into paper pulp for nest-building purposes. ; And they are

strong, large, toothed and horny in substance, joined to the sides of the head

below the eyes, and, as is usual in insects, working sideways.

She likes, to vary her diet of fruits and sweets

with an occasional insect, which she is very skilful in catching. She is

particularly fond of flies, though nothing seems to come amiss, and she bears

out her reputation of liking ill-smelling food by devouring the malodorous white

cabbage butterfly and the offensive earwig, both of which are left severely

alone by even the hungriest of insectivorous birds. She also likes raw meat, to

which she willingly helps herself from the butcher's shop, without troubling him

to wait on her. The butcher ought to welcome her, as the small amount of meat

she consumes is more than paid for in the large number of flies she catches,

thus protecting him from one of the greatest nuisances he has to contend with.

But butchers are not always grateful for their blessings, and one once clipped

the wings of the wasps engaged in carrying off his meat, to punish them for the

theft. Never before had they been obliged to face such an emergency, and finding

themselves unable to fly, their wasp minds, searching for a cause and relying

upon past experience to supply it, naturally concluded they had carved out too

heavy a steak, and they set to work cutting their pieces of meat smaller and

smaller. Poor little fellows! What happened when the fragments had been reduced

to the smallest possible size and the wings still refused to perform their

office, the record does not state, but surely there was material for tragedy in

the annals of waspdom.

Besides eating animal food herself, Vespa carries it home to feed the larvae in the nest.

Wasps doubtless deserve far more credit than they usually get for their services as fly-catchers. Mr. Wood, in his “Homes without Hands,” tells of pigs lying in the warm sunshine covered with flies which wasps pounced upon and carried away.

Another observer watched wasps catching flies on two cows, and in twenty minutes saw between three and four hundred snatched off.

It is to be hoped the cows were properly grateful.

In some parts of our own country, farmers' wives are reported to have taken advantage of the wasp's well-known fondness for flies by hanging a wasp's-nest in the house. Doubtless such a fly-trap, with a little care and patience, would work admirably, as wasps readily make friends of people whom they are in the habit of seeing close to their nests, and who do not molest them. However, the present writer does not seriously recommend the practice as a substitute for window-screens and fly-poison.

No doubt the wasps do a great, though unrecognised service, in keeping the flies in check, as was once proved on an estate in England, where all the female wasps were hunted and killed one spring before they had a chance to start their nests. The wasps were sacrificed in order to save the fruit in the fall from their depredations. The fruit was spared, but for two years the estate “was infested, like Egypt, with a plague of flies.”

Doubtless wasps are valuable scavengers in hot countries, where they are very numerous, and where they have been known to consume large quantities of refuse, and even to keep the butchers' stalls sweet and clean. In our country the wasps that live near human habitations do their share as scavengers. Once these little insect vultures were observed to clean the bones of a dead mouse in two days.

An interesting writer in a British periodical

tells of sitting in the open air and being visited by wasps that wished to share

his lunch. The first day they were some time finding the lunch-bag, but the next

day they recognised it and their entertainer, and were on hand clustered on the

bag ready for the feast before there was time to undo the strap. Some bread and

jelly and a small piece id bacon and butter were hung on the hedge to lure away

the rather inconvenient guests, and these things they caused to disappear, --

all but a small piece of hard bread.

An interesting writer in a British periodical

tells of sitting in the open air and being visited by wasps that wished to share

his lunch. The first day they were some time finding the lunch-bag, but the next

day they recognised it and their entertainer, and were on hand clustered on the

bag ready for the feast before there was time to undo the strap. Some bread and

jelly and a small piece id bacon and butter were hung on the hedge to lure away

the rather inconvenient guests, and these things they caused to disappear, --

all but a small piece of hard bread.

The same observer found a great difference in wasps near dwellings and those living in the deep woods. The latter took no interest in lunch-bags, not having, had experience with food prepared by man, and they were not inclined to make the acquaintance of their human guest. Those living by the roadside, however, visited him as he sat painting, getting on his collar and his arm and even allowing him to stroke them gently on the back.

Indeed wasps differ as much as cats in their habits of friendliness. One cannot make friends with a puss that has run wild in the woods, perhaps was born in the hollow of a tree, as one can with a household pet. Neither do the wasps of the forest become friendly like those of the wayside.

A yellow-jacket's nest was once built in the ground on a vacant lot in a large city. People constantly passed within three feet of it, and mischievous boys had stoned the entrance to the nest until there was a little mound of stones to mark the spot. The wasps rushed out when stoned and stung the boys, but they never molested a passer-by under ordinary circumstances. Indeed one could stand close to the nest and watch them hurrying in and out, whizzing past one's head back and forth, showing no resentment and paying no attention to their visitor.

If one wishes the sensation of taking a live hornet in the hand, it can be safely done by putting a drop of syrup on the end of the finger and offering it to a hungry caged hornet. One should move gently, slowly, invitingly, and her ladyship, forgetting all cause for resentment in the joy of discovering food, will climb in a friendly way upon the offered finger; and no wasp is ever dastardly enough to sting a finger upon which it voluntarily and in a calm frame of mind has climbed, that is, unless it becomes frightened before it leaves of its own accord.

It is never safe to frighten hornets. Sometimes her ladyship finds the warm finger attractive for its own sake, and particularly on a chilly day will sit contentedly panting her abdomen after the syrup is eaten and the holder is quite ready to end the experiment and return the wasp to her cage.

This can be done by gently placing a slip of paper in front of her and shoving her off the finger, or if the nerve fails, a quick flip will safely dislodge her.

In dealing with hornets the main thing is to be perfectly calm and self-possessed. A nervous thrill of fear seems to be communicated by some occult process to Vespa's nerve centres as well, and a frightened hornet is always a fighting hornet.