|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

WASP-FLOWERS.

THE wasps love the flowers, and from early

spring to late fall may be seen flying about them.

They appear to be very exclusive in their tastes, as they are found upon only a few plants, whereas bees may be found upon almost anything that blossoms. This is not due to a capricious appetite, but doubtless to the size of the tongue, for the little flat ligula of the hornets and yellow-jackets cannot reach to the nectary of most flowers.

The wasp is a philosopher, however, who does not waste power worrying over delectable sweets just out of reach.

“Go to!” it seems to say; “there are other flowers, more generous and with equally dainty sweets;” and these it seeks and joyfully rifles, turning no longing gaze towards the honeyful spurs and cups not open to its enjoyment.

There are certain flowers that may be justly

called wasp-flowers, because the head of the wasp and the cup of the flower fit

each other so prettily. One of these is the figwort. There are two species of

this odd plant in our country, the Maryland figwort, which blossoms later and

grows larger, and the early smaller Hare figwort.

These are common weeds that might be passed a thousand times without notice, because the flowers are small and inconspicuous, but when one knows they are wasp-flowers they at once become more interesting.

The figwort grows abundantly where it does grow, and in good soil the larger species attains a height of eight or ten feet, though it is usually from three to five feet tall.

The figwort is quite a charming plant, when one stops to look at it; its clusters of small purple-green flowers, light and airy on their slender stems making a pretty pattern against the sky. But the principal interest attaching to it is in the shape and size of its blossoms.

These little green and purple urns are just large enough to receive the head and chest of a hornet or yellow-jacket, and when the little creatures fit themselves into its accommodating bosom they find its nectar neither hidden nor to be reached only through long and slender tubes, as is the case with so many bee-flowers.

No, this figwort nectar lies within easy reach at the bottom of the little urn, ready to yield itself abundantly to the short flat tongues of hungry hornets and yellow-jackets. And about these flowers on sunny days the hornets and yellow-jackets can always be found.

Bees too visit them, for their honey is abundant, and the bees find them, notwithstanding their dull colours, quite as readily as do the wasps.

But there are many wasps to one bee about the

figworts, which at that season of the year are often the only flowers in bloom

that yield tribute to wasps, while the bees can satisfy themselves at other

fountains.

The figwort is a cunning schemer, whose dainty green or purple urns do not stand filled with nectar with no other purpose than the pleasure of the wasps and bees. They go to it for honey, and this it graciously gives, then makes them the bearers of its pollen grains. To it they bring pollen from neighbouring figworts; from it they bear pollen.

The figwort holds its ripened pistil forth in the passage-way to its banquet hall, and whoever enters must brush the ready stigma. Thus, sooner or later, it is sure to receive the pollen it desires from its distant neighbours.

Once dusted with pollen the pistil turns down out of the way over the lower lip of the urn, and the stamens then present themselves, ripe and ready to dust the honey-seekers with plenteous pollen to be carried to neighbouring figworts.

This service of pollen-carrying the wasps must perform, whether they like it or not, and they do not seem to like it, for wasps do not gather pollen for food as do bees, and it is only a nuisance to them.

They often stop to brush it off, but enough grains cling to them to serve the purpose of the flowers visited.

The figwort has a hood over its head formed by the borders of the upper petals ; and this is one of the prettiest things about it.

The wasp goes in under this hood, which rises as the bud unfolds, and reveals the opening to the flower urn.

Moreover, when it rains the flower droops a little on its stem, and the hood also draws forward slightly, so as to protect the precious contents of the urn -- the nectar and pollen-from the rain.

When the sun shines the flower straightens up, as does also the hood.

In figwort season the laurel too opens, and then do the mountains of its choice blossom like gardens. The observer looks with amazed admiration upon undulating banks of solid bloom-walling in the path he treads. Through the openings in these banks, slopes in the distance shine white as snow or glow rosy red. The wilder the mountain, the mightier its outburst of laurel beauty.

The shallow cups of the flowers invite the approach of the wasps, who also frequent the safe recesses of the mountains, where to the branches of the trees they hang their paper homes.

The laurel is not specially a wasp-flower, though these insects seek its easily reached nectar upon occasion, and no doubt are valuable agents in carrying the pollen which the laurel conceals in a curious and very ingenious manner until the time of its ripening. The stamens are bent over like springs, the anthers being caught in little pockets or depressions in the corolla.

When the wasp seeks nectar its restless legs loosen the stamen springs, and up fly the anthers, throwing pollen as out of a sling, often quite over the bush to a neighbouring plant, and often against the body of the wasp, that, after being pelted with pollen, is in a condition to cross-fertilise the next laurel flower it visits.

The Alleghany Menzesia is a plant the wasps

delight in. It belongs to the Heath Family, and has a bush like an azalea, but

flowers like those of a huckleberry, though larger.

The Alleghany Menzesia is a plant the wasps

delight in. It belongs to the Heath Family, and has a bush like an azalea, but

flowers like those of a huckleberry, though larger.

Indeed these flowers are just large enough to allow the hungry Vespa to get her head into the nectar stored at the bottom of the little flower urn.

The Menzesia grows in the Alleghany Mountains, and one lovely mountain top in Virginia in the spring is covered with beautiful bushes of it, every flower cluster having its little band of wasp votaries.

The pretty snowberry blossoms that make charming the northern mountains are also wasp flowers. This dainty little plant creeps over mossy banks, and in May and June puts forth the small white flowers that are succeeded by snowy berries having a flavour of birch.

The pretty bell-shaped blossoms are of the right size to accommodate the head of Vespa, and, she has the good taste to be fond of snowberry honey.

The sweet-clover also yields its delicious nectar to the short tongues of the hornets and yellow-jackets, - a fact of which they are not slow to take advantage, as the visitors buzzing about the sweet-clover beds that line many roadsides bear witness.

Vespa enjoys the goldenrods too, and in the fall of the year may be captured quite easily as she buries her face in the polleny masses, oblivious for once to whoever may be coming near with suspended net and evil intent.

It is commonly said that wasps are attracted to flowers having a disagreeable or meat-like odour.

This may be true to some extent, though it seems probable that the structure of the flower has more influence upon the visits of wasps than the odour. Certain flies do prefer ill-smelling flowers, and the wasps, finding the nectar of these flat-topped blooms obtainable by their short tongues, may visit them also, though they by no means confine their attention to such. They may not be quite as dainty as the bees in their choice of food, but it is a libel to accuse them of preferring ill-smelling blossoms if they can find sweet ones.

They are very fond of honey, syrup, and all sweets, and eagerly suck the sap from bleeding trees in the spring of the year.

Like the bees they have a weakness for fermented drinks, and they are immoral enough to abandon themselves to whatever satisfaction comes from intoxication, eagerly drinking sweet wine, or sugar and water containing alcoholic liquor. If their drink is but sweet enough they joyfully imbibe until they are quite drunk. They frequent nature's wine-shops too, drinking the juices of fermented fruits, and after an orgy under a tree whose over-ripe fruit strews the ground, they may be seen lying around in a state of helpless drunkenness.

As they recover they stagger about in a feeble and tipsy manner absurdly suggestive of the members of a higher race when in the same unfortunate condition.

Their misdoings do not prevent their being

valuable to the plant world. Probably they are important fertilising agents to

all flowers whose nectar their tongues can reach, and it is known that several

plants are entirely dependent upon them for cross-fertilisation.

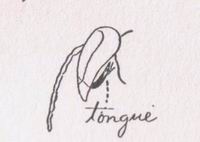

The tongue of Vespa, the wasp, differs very much in structure from that of Apis, the bee, for the Apis' tongue is modified into a long, sucking proboscis, while the mouth organs of Vespa are not very much specialised. The upper lip folds down and hides the tongue when the latter is at rest. Below the upper lip is a portion which consists of a four-parted tongue and two feelers, one on each side.

Underneath this are two horny parts, which bear each a feeler.

The feelers probably aid the wasp in exactly

locating, and perhaps in deciding the quality of, its food. The tongue as a

whole enables it to lick up easily reached liquids, but it is quite unable to

reach concealed or distant nectar.

When not in use the tongue is drawn in and back,

where it fits in a groove behind the head. When in use it appears as a little

flat tongue, so like that of a dog in motion and appearance, as one watches it

at a distance, that one is surprised and delighted with the first view of a wasp

dining in captivity. It is very difficult to see it dining excepting in

captivity, as the social wasps are usually so wary that one cannot get near

enough to watch them on the flowers out-of-doors. In nest-making time, however,

when they are engaged in cutting up insects or bits of meat for transportation

they become so oblivious to the rest of the world that one can not only watch

them at short range, but even clip their wings.

When not in use the tongue is drawn in and back,

where it fits in a groove behind the head. When in use it appears as a little

flat tongue, so like that of a dog in motion and appearance, as one watches it

at a distance, that one is surprised and delighted with the first view of a wasp

dining in captivity. It is very difficult to see it dining excepting in

captivity, as the social wasps are usually so wary that one cannot get near

enough to watch them on the flowers out-of-doors. In nest-making time, however,

when they are engaged in cutting up insects or bits of meat for transportation

they become so oblivious to the rest of the world that one can not only watch

them at short range, but even clip their wings.