| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

The Pygmies. A great while ago,

when the world was full of wonders, there lived an

earth-born Giant, named AntŠus, and a million or more of curious little

earth-born people, who were called Pygmies. This Giant and these

Pygmies being

children of the same mother (that is to say, our good old Grandmother

Earth),

were all brethren, and dwelt together in a very friendly and

affectionate

manner, far, far off, in the middle of hot Africa. The Pygmies were so

small,

and there were so many sandy deserts and such high mountains between

them and

the rest of mankind, that nobody could get a peep at them oftener than

once in

a hundred years. As for the Giant, being of a very lofty stature, it

was easy

enough to see him, but safest to keep out of his sight. Among the Pygmies, I

suppose, if one of them grew to the height of six

or eight inches, he was reckoned a prodigiously tall man. It must have

been

very pretty to behold their little cities, with streets two or three

feet wide,

paved with the smallest pebbles, and bordered by habitations about as

big as a squirrel's

cage. The king's palace attained to the stupendous magnitude of

Periwinkle's

baby house, and stood in the center of a spacious square, which could

hardly

have been covered by our hearth-rug. Their principal temple, or

cathedral, was

as lofty as yonder bureau, and was looked upon as a wonderfully sublime

and

magnificent edifice. All these structures were built neither of stone

nor wood.

They were neatly plastered together by the Pygmy workmen, pretty much

like

birds' nests, out of straw, feathers, egg shells, and other small bits

of

stuff, with stiff clay instead of mortar; and when the hot sun had

dried them,

they were just as snug and comfortable as a Pygmy could desire. The country round

about was conveniently laid out in fields, the largest

of which was nearly of the same extent as one of Sweet Fern's flower

beds. Here

the Pygmies used to plant wheat and other kinds of grain, which, when

it grew

up and ripened, overshadowed these tiny people as the pines, and the

oaks, and

the walnut and chestnut trees overshadow you and me, when we walk in

our own

tracts of woodland. At harvest time, they were forced to go with their

little

axes and cut down the grain, exactly as a woodcutter makes a clearing

in the

forest; and when a stalk of wheat, with its overburdened top, chanced

to come

crashing down upon an unfortunate Pygmy, it was apt to be a very sad

affair. If

it did not smash him all to pieces, at least, I am sure, it must have

made the

poor little fellow's head ache. And O, my stars! if the fathers and

mothers

were so small, what must the children and babies have been? A whole

family of

them might have been put to bed in a shoe, or have crept into an old

glove, and

played at hide-and-seek in its thumb and fingers. You might have hidden

a

year-old baby under a thimble. Now these funny

Pygmies, as I told you before, had a Giant for their

neighbor and brother, who was bigger, if possible, than they were

little. He

was so very tall that he carried a pine tree, which was eight feet

through the

butt, for a walking stick. It took a far-sighted Pygmy, I can assure

you, to

discern his summit without the help of a telescope; and sometimes, in

misty

weather, they could not see his upper half, but only his long legs,

which

seemed to be striding about by themselves. But at noonday in a clear

atmosphere, when the sun shone brightly over him, the Giant AntŠus

presented a

very grand spectacle. There he used to stand, a perfect mountain of a

man, with

his great countenance smiling down upon his little brothers, and his

one vast

eye (which was as big as a cart wheel, and placed right in the center

of his

forehead) giving a friendly wink to the whole nation at once. The Pygmies loved to

talk with AntŠus; and fifty times a day, one or

another of them would turn up his head, and shout through the hollow of

his

fists, "Halloo, brother AntŠus! How are you, my good fellow?" And

when the small distant squeak of their voices reached his ear, the

Giant would

make answer, "Pretty well, brother Pygmy, I thank you," in a

thunderous roar that would have shaken down the walls of their

strongest

temple, only that it came from so far aloft. It was a happy

circumstance that AntŠus was the Pygmy people's friend;

for there was more strength in his little finger than in ten million of

such bodies

as this. If he had been as ill-natured to them as he was to everybody

else, he

might have beaten down their biggest city at one kick, and hardly have

known

that he did it. With the tornado of his breath, he could have stripped

the

roofs from a hundred dwellings and sent thousands of the inhabitants

whirling

through the air. He might have set his immense foot upon a multitude;

and when

he took it up again, there would have been a pitiful sight, to be sure.

But,

being the son of Mother Earth, as they likewise were, the Giant gave

them his

brotherly kindness, and loved them with as big a love as it was

possible to

feel for creatures so very small. And, on their parts, the Pygmies

loved AntŠus

with as much affection as their tiny hearts could hold. He was always

ready to

do them any good offices that lay in his power; as for example, when

they

wanted a breeze to turn their windmills, the Giant would set all the

sails

a-going with the mere natural respiration of his lungs. When the sun

was too

hot, he often sat himself down, and let his shadow fall over the

kingdom, from

one frontier to the other; and as for matters in general, he was wise

enough to

let them alone, and leave the Pygmies to manage their own affairs Ś

which,

after all, is about the best thing that great people can do for little

ones. In short, as I said

before, AntŠus loved the Pygmies, and the Pygmies

loved AntŠus. The Giant's life being as long as his body was large,

while the

lifetime of a Pygmy was but a span, this friendly intercourse had been

going on

for innumerable generations and ages. It was written about in the Pygmy

histories, and talked about in their ancient traditions. The most

venerable and

white-bearded Pygmy had never heard of a time, even in his greatest of

grandfathers' days, when the Giant was not their enormous friend. Once,

to be

sure (as was recorded on an obelisk, three feet high, erected on the

place of

the catastrophe), AntŠus sat down upon about five thousand Pygmies, who

were

assembled at a military review. But this was one of those unlucky

accidents for

which nobody is to blame; so that the small folks never took it to

heart, and

only requested the Giant to be careful forever afterwards to examine

the acre

of ground where he intended to squat himself. It is a very

pleasant picture to imagine AntŠus standing among the

Pygmies, like the spire of the tallest cathedral that ever was built,

while

they ran about like pismires at his feet; and to think that, in spite

of their

difference in size, there were affection and sympathy between them and

him!

Indeed, it has always seemed to me that the Giant needed the little

people more

than the Pygmies needed the Giant. For, unless they had been his

neighbors and

well wishers, and, as we may say, his playfellows, AntŠus would not

have had a

single friend in the world. No other being like himself had ever been

created.

No creature of his own size had ever talked with him, in thunder-like

accents,

face to face. When he stood with his head among the clouds, he was

quite alone,

and had been so for hundreds of years, and would be so forever. Even if

he had

met another Giant, AntŠus would have fancied the world not big enough

for two

such vast personages, and, instead of being friends with him, would

have fought

him till one of the two was killed. But with the Pygmies he was the

most

sportive and humorous, and merry-hearted, and sweet-tempered old Giant

that

ever washed his face in a wet cloud. His little friends,

like all other small people, had a great opinion of

their own importance, and used to assume quite a patronizing air

towards the

Giant. "Poor creature!"

they said one to another. "He has a very

dull time of it, all by himself; and we ought not to grudge wasting a

little of

our precious time to amuse him. He is not half so bright as we are, to

be sure;

and, for that reason, he needs us to look after his comfort and

happiness. Let

us be kind to the old fellow. Why, if Mother Earth had not been very

kind to

ourselves, we might all have been Giants too." On all their

holidays, the Pygmies had excellent sport with AntŠus. He

often stretched himself out at full length on the ground, where he

looked like

the long ridge of a hill; and it was a good hour's walk, no doubt, for

a

short-legged Pygmy to journey from head to foot of the Giant. He would

lay down

his great hand flat on the grass, and challenge the tallest of them to

clamber

upon it, and straddle from finger to finger. So fearless were they,

that they

made nothing of creeping in among the folds of his garments. When his

head lay sidewise

on the earth, they would march boldly up, and peep into the great

cavern of his

mouth, and take it all as a joke (as indeed it was meant) when AntŠus

gave a

sudden snap of his jaws, as if he were going to swallow fifty of them

at once.

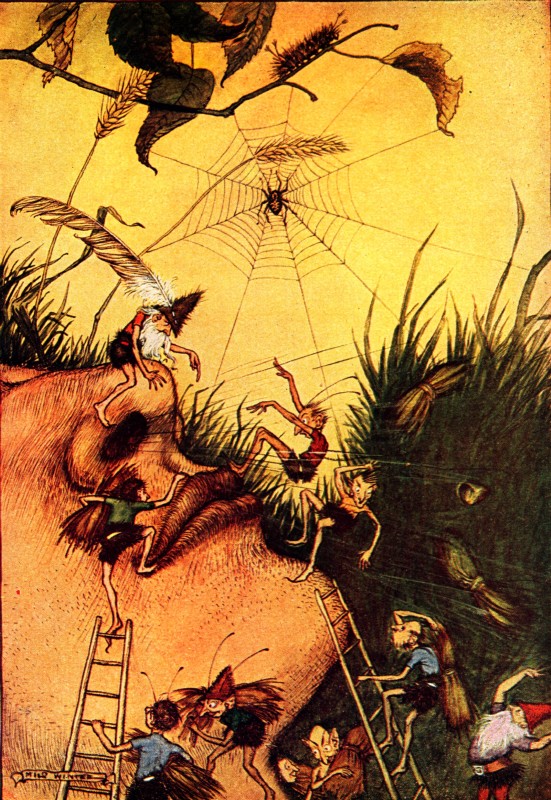

You would have laughed to see the children dodging in and out among his

hair,

or swinging from his beard. It is impossible to tell half of the funny

tricks

that they played with their huge comrade; but I do not know that

anything was

more curious than when a party of boys were seen running races on his

forehead,

to try which of them could get first round the circle of his one great

eye. It

was another favorite feat with them to march along the bridge of his

nose, and

jump down upon his upper lip. If the truth must be

told, they were sometimes as troublesome to the

Giant as a swarm of ants or mosquitoes, especially as they had a

fondness for

mischief, and liked to prick his skin with their little swords and

lances, to

see how thick and tough it was. But AntŠus took it all kindly enough;

although,

once in a while, when he happened to be sleepy, he would grumble out a

peevish

word or two, like the muttering of a tempest, and ask them to have done

with

their nonsense. A great deal oftener, however, he watched their

merriment and

gambols until his huge, heavy, clumsy wits were completely stirred up

by them;

and then would he roar out such a tremendous volume of immeasurable

laughter,

that the whole nation of Pygmies had to put their hands to their ears,

else it

would certainly have deafened them. "Ho! ho! ho!" quoth

the Giant, shaking his mountainous sides.

"What a funny thing it is to be little! If I were not AntŠus, I should

like to be a Pygmy, just for the joke's sake." The Pygmies had but

one thing to trouble them in the world. They were

constantly at war with the cranes, and had always been so, ever since

the

long-lived Giant could remember. From time to time, very terrible

battles had

been fought in which sometimes the little men won the victory, and

sometimes

the cranes. According to some historians, the Pygmies used to go to the

battle,

mounted on the backs of goats and rams; but such animals as these must

have

been far too big for Pygmies to ride upon; so that, I rather suppose,

they rode

on squirrel-back, or rabbit-back, or rat-back, or perhaps got upon

hedgehogs,

whose prickly quills would be very terrible to the enemy. However this

might

be, and whatever creatures the Pygmies rode upon, I do not doubt that

they made

a formidable appearance, armed with sword and spear, and bow and arrow,

blowing

their tiny trumpet, and shouting their little war cry. They never

failed to

exhort one another to fight bravely, and recollect that the world had

its eyes

upon them; although, in simple truth, the only spectator was the Giant

AntŠus,

with his one, great, stupid eye in the middle of his forehead. When the two armies

joined battle, the cranes would rush forward,

flapping their wings and stretching out their necks, and would perhaps

snatch

up some of the Pygmies crosswise in their beaks. Whenever this

happened, it was

truly an awful spectacle to see those little men of might kicking and

sprawling

in the air, and at last disappearing down the crane's long, crooked

throat,

swallowed up alive. A hero, you know, must hold himself in readiness

for any

kind of fate; and doubtless the glory of the thing was a consolation to

him,

even in the crane's gizzard. If AntŠus observed that the battle was

going hard

against his little allies, he generally stopped laughing, and ran with

mile-long strides to their assistance, flourishing his club aloft and

shouting

at the cranes, who quacked and croaked, and retreated as fast as they

could. Then

the Pygmy army would march homeward in triumph, attributing the victory

entirely to their own valor, and to the warlike skill and strategy of

whomsoever

happened to be captain general; and for a tedious while afterwards,

nothing

would be heard of but grand processions, and public banquets, and

brilliant

illuminations, and shows of wax-work, with likenesses of the

distinguished

officers, as small as life. In the

above-described warfare, if a Pygmy chanced to pluck out a

crane's tail feather, it proved a very great feather in his cap. Once

or twice,

if you will believe me, a little man was made chief ruler of the nation

for no

other merit in the world than bringing home such a feather. But I have now said

enough to let you see what a gallant little people

these were, and how happily they and their forefathers, for nobody

knows how

many generations, had lived with the immeasurable Giant AntŠus. In the

remaining part of the story, I shall tell you of a far more astonishing

battle

than any that was fought between the Pygmies and the cranes. One day the mighty

AntŠus was lolling at full length among his little

friends. His pine-tree walking stick lay on the ground, close by his

side. His

head was in one part of the kingdom, and his feet extended across the

boundaries of another part; and he was taking whatever comfort he could

get,

while the Pygmies scrambled over him, and peeped into his cavernous

mouth, and

played among his hair. Sometimes, for a minute or two, the Giant

dropped

asleep, and snored like the rush of a whirlwind. During one of these

little

bits of slumber, a Pygmy chanced to climb upon his shoulder, and took a

view

around the horizon, as from the summit of a hill; and he beheld

something, a

long way off, which made him rub the bright specks of his eyes, and

look

sharper than before. At first he mistook it for a mountain, and

wondered how it

had grown up so suddenly out of the earth. But soon he saw the mountain

move.

As it came nearer and nearer, what should it turn out to be but a human

shape,

not so big as AntŠus, it is true, although a very enormous figure, in

comparison with Pygmies, and a vast deal bigger than the men we see

nowadays. When the Pygmy was

quite satisfied that his eyes had not deceived him,

he scampered, as fast as his legs would carry him, to the Giant's ear,

and

stooping over its cavity, shouted lustily into it: "Halloo, brother

AntŠus! Get up this minute, and take your

pine-tree walking stick in your hand. Here comes another Giant to have

a tussle

with you." "Poh, poh!" grumbled

AntŠus, only half awake. "None of

your nonsense, my little fellow! Don't you see I'm sleepy? There is not

a Giant

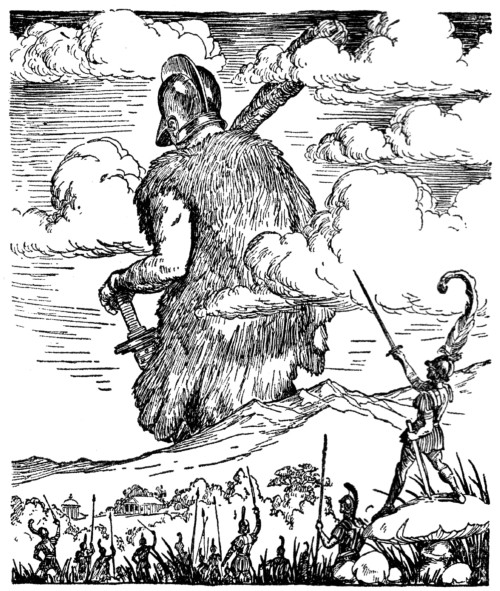

on earth for whom I would take the trouble to get up." But the Pygmy looked

again, and now perceived that the stranger was

coming directly towards the prostrate form of AntŠus. With every step,

he

looked less like a blue mountain, and more like an immensely large man.

He was

soon so nigh, that there could be no possible mistake about the matter.

There

he was, with the sun flaming on his golden helmet, and flashing from

his

polished breastplate; he had a sword by his side, and a lion's skin

over his

back, and on his right shoulder he carried a club, which looked bulkier

and

heavier than the pine-tree walking stick of AntŠus. By this time, the

whole nation of the Pygmies had seen the new wonder,

and a million of them set up a shout all together; so that it really

made quite

an audible squeak. "Get up, AntŠus!

Bestir yourself, you lazy old Giant! Here comes

another Giant, as strong as you are, to fight with you." "Nonsense,

nonsense!" growled the sleepy Giant. "I'll

have my nap out, come who may." Still the stranger

drew nearer; and now the Pygmies could plainly

discern that, if his stature were less lofty than the Giant's, yet his

shoulders were even broader. And, in truth, what a pair of shoulders

they must

have been! As I told you, a long while ago, they once upheld the sky.

The

Pygmies, being ten times as vivacious as their great numskull of a

brother,

could not abide the Giant's slow movements, and were determined to have

him on

his feet. So they kept shouting to him, and even went so far as to

prick him

with their swords. "Get up, get up, get

up," they cried. "Up with you, lazy

bones! The strange Giant's club is bigger than your own, his shoulders

are the

broadest, and we think him the stronger of the two." AntŠus could not

endure to have it said that any mortal was half so

mighty as himself. This latter remark of the Pygmies pricked him deeper

than

their swords; and, sitting up, in rather a sulky humor, he gave a gape

of

several yards wide, rubbed his eyes, and finally turned his stupid head

in the

direction whither his little friends were eagerly pointing. No sooner did he set

eyes on the stranger, than, leaping on his feet,

and seizing his walking stick, he strode a mile or two to meet him; all

the

while brandishing the sturdy pine tree, so that it whistled through the

air. "Who are you?"

thundered the Giant. "And what do you want

in my dominions?" There was one

strange thing about AntŠus, of which I have not yet told

you, lest, hearing of so many wonders all in a lump, you might not

believe much

more than half of them. You are to know, then, that whenever this

redoubtable

Giant touched the ground, either with his hand, his foot, or any other

part of

his body, he grew stronger than ever he had been before. The Earth, you

remember, was his mother, and was very fond of him, as being almost the

biggest

of her children; and so she took this method of keeping him always in

full

vigor. Some persons affirm that he grew ten times stronger at every

touch;

others say that it was only twice as strong. But only think of it!

Whenever AntŠus

took a walk, supposing it were but ten miles, and that he stepped a

hundred

yards at a stride, you may try to cipher out how much mightier he was,

on

sitting down again, than when he first started. And whenever he flung

himself

on the earth to take a little repose, even if he got up the very next

instant,

he would be as strong as exactly ten just such giants as his former

self. It

was well for the world that AntŠus happened to be of a sluggish

disposition and

liked ease better than exercise; for, if he had frisked about like the

Pygmies,

and touched the earth as often as they did, he would long ago have been

strong

enough to pull down the sky about people's ears. But these great

lubberly

fellows resemble mountains, not only in bulk, but in their

disinclination to

move. Any other mortal

man, except the very one whom AntŠus had now

encountered, would have been half frightened to death by the Giant's

ferocious

aspect and terrible voice. But the stranger did not seem at all

disturbed. He

carelessly lifted his club, and balanced it in his hand, measuring

AntŠus with

his eye, from head to foot, not as if wonder-smitten at his stature,

but as if

he had seen a great many Giants before, and this was by no means the

biggest of

them. In fact, if the Giant had been no bigger than the Pygmies (who

stood

pricking up their ears, and looking and listening to what was going

forward),

the stranger could not have been less afraid of him. "Who are you, I

say?" roared AntŠus again. "What's your

name? Why do you come hither? Speak, you vagabond, or I'll try the

thickness of

your skull with my walking-stick!" "You are a very

discourteous Giant," answered the stranger

quietly, "and I shall probably have to teach you a little civility,

before

we part. As for my name, it is Hercules. I have come hither because

this is my

most convenient road to the garden of the Hesperides, whither I am

going to get

three of the golden apples for King Eurystheus." "Caitiff, you shall

go no farther!" bellowed AntŠus, putting

on a grimmer look than before; for he had heard of the mighty Hercules,

and

hated him because he was said to be so strong. "Neither shall you go

back

whence you came!" "How will you

prevent me," asked Hercules, "from going

whither I please?" "By hitting you a

rap with this pine tree here," shouted AntŠus,

scowling so that he made himself the ugliest monster in Africa. "I am

fifty times stronger than you; and now that I stamp my foot upon the

ground, I

am five hundred times stronger! I am ashamed to kill such a puny little

dwarf

as you seem to be. I will make a slave of you, and you shall likewise

be the

slave of my brethren here, the Pygmies. So throw down your club and

your other

weapons; and as for that lion's skin, I intend to have a pair of gloves

made of

it." "Come and take it

off my shoulders, then," answered Hercules,

lifting his club. Then the Giant,

grinning with rage, strode tower-like towards the

stranger (ten times strengthened at every step), and fetched a

monstrous blow

at him with his pine tree, which Hercules caught upon his club; and

being more

skilful than AntŠus, he paid him back such a rap upon the sconce, that

down

tumbled the great lumbering man-mountain, flat upon the ground. The

poor little

Pygmies (who really never dreamed that anybody in the world was half so

strong

as their brother AntŠus) were a good deal dismayed at this. But no

sooner was

the Giant down, than up he bounced again, with tenfold might, and such

a

furious visage as was horrible to behold. He aimed another blow at

Hercules,

but struck awry, being blinded with wrath, and only hit his poor

innocent

Mother Earth, who groaned and trembled at the stroke. His pine tree

went so

deep into the ground, and stuck there so fast, that, before AntŠus

could get it

out, Hercules brought down his club across his shoulders with a mighty

thwack,

which made the Giant roar as if all sorts of intolerable noises had

come

screeching and rumbling out of his immeasurable lungs in that one cry.

Away it

went, over mountains and valleys, and, for aught I know, was heard on

the other

side of the African deserts. As for the Pygmies,

their capital city was laid in ruins by the

concussion and vibration of the air; and, though there was uproar

enough

without their help, they all set up a shriek out of three millions of

little

throats, fancying, no doubt, that they swelled the Giant's bellow by at

least

ten times as much. Meanwhile, AntŠus had scrambled upon his feet again,

and

pulled his pine tree out of the earth; and, all aflame with fury, and

more

outrageously strong than ever, he ran at Hercules, and brought down

another

blow. "This time, rascal,"

shouted he, "you shall not escape

me." But once more

Hercules warded off the stroke with his club, and the

Giant's pine tree was shattered into a thousand splinters, most of

which flew

among the Pygmies, and did them more mischief than I like to think

about.

Before AntŠus could get out of the way, Hercules let drive again, and

gave him

another knock-down blow, which sent him heels over head, but served

only to

increase his already enormous and insufferable strength. As for his

rage, there

is no telling what a fiery furnace it had now got to be. His one eye

was

nothing but a circle of red flame. Having now no weapons but his fists,

he

doubled them up (each bigger than a hogshead), smote one against the

other, and

danced up and down with absolute frenzy, flourishing his immense arms

about, as

if he meant not merely to kill Hercules, but to smash the whole world

to

pieces. "Come on!" roared

this thundering Giant. "Let me hit you

but one box on the ear, and you'll never have the headache again." Now Hercules (though

strong enough, as you already know, to hold the sky

up) began to be sensible that he should never win the victory, if he

kept on

knocking AntŠus down; for, by and by, if he hit him such hard blows,

the Giant

would inevitably, by the help of his Mother Earth, become stronger than

the

mighty Hercules himself. So, throwing down his club, with which he had

fought

so many dreadful battles, the hero stood ready to receive his

antagonist with

naked arms. "Step forward,"

cried he. "Since I've broken your pine

tree, we'll try which is the better man at a wrestling match." "Aha! then I'll soon

satisfy you," shouted the Giant; for, if

there was one thing on which he prided himself more than another, it

was his

skill in wrestling. "Villain, I'll fling you where you can never pick

yourself up again." On came AntŠus,

hopping and capering with the scorching heat of his

rage, and getting new vigor wherewith to wreak his passion, every time

he

hopped. But Hercules, you

must understand, was wiser than this numskull of a

Giant, and had thought of a way to fight him Ś huge, earth-born monster

that he

was Ś and to conquer him too, in spite of all that his Mother Earth

could do

for him. Watching his opportunity, as the mad Giant made a rush at him,

Hercules caught him round the middle with both hands, lifted him high

into the

air, and held him aloft overhead. Just imagine it, my

dear little friends. What a spectacle it must have

been, to see this monstrous fellow sprawling in the air, face

downwards,

kicking out his long legs and wriggling his whole vast body, like a

baby when

its father holds it at arm's length towards the ceiling. But the most

wonderful thing was, that, as soon as AntŠus was fairly off

the earth, he began to lose the vigor which he had gained by touching

it.

Hercules very soon perceived that his troublesome enemy was growing

weaker,

both because he struggled and kicked with less violence, and because

the

thunder of his big voice subsided into a grumble. The truth was that

unless the

Giant touched Mother Earth as often as once in five minutes, not only

his

overgrown strength, but the very breath of his life, would depart from

him.

Hercules had guessed this secret; and it may be well for us all to

remember it,

in case we should ever have to fight a battle with a fellow like

AntŠus. For

these earth-born creatures are only difficult to conquer on their own

ground,

but may easily be managed if we can contrive to lift them into a

loftier and

purer region. So it proved with the poor Giant, whom I am really a

little sorry

for, notwithstanding his uncivil way of treating strangers who came to

visit

him. When his strength

and breath were quite gone, Hercules gave his huge

body a toss, and flung it about a mile off, where it fell heavily, and

lay with

no more motion than a sand hill. It was too late for the Giant's Mother

Earth

to help him now; and I should not wonder if his ponderous bones were

lying on the

same spot to this very day, and were mistaken for those of an

uncommonly large

elephant. But, alas me! What a

wailing did the poor little Pygmies set up when

they saw their enormous brother treated in this terrible manner! If

Hercules

heard their shrieks, however, he took no notice, and perhaps fancied

them only

the shrill, plaintive twittering of small birds that had been

frightened from

their nests by the uproar of the battle between himself and AntŠus.

Indeed, his

thoughts had been so much taken up with the Giant, that he had never

once

looked at the Pygmies, nor even knew that there was such a funny little

nation

in the world. And now, as he had traveled a good way, and was also

rather weary

with his exertions in the fight, he spread out his lion's skin on the

ground,

and, reclining himself upon it, fell fast asleep. As soon as the

Pygmies saw Hercules preparing for a nap, they nodded

their little heads at one another, and winked with their little eyes.

And when

his deep, regular breathing gave them notice that he was asleep, they

assembled

together in an immense crowd, spreading over a space of about

twenty-seven feet

square. One of their most eloquent orators (and a valiant warrior

enough,

besides, though hardly so good at any other weapon as he was with his

tongue)

climbed upon a toadstool, and, from that elevated position, addressed

the

multitude. His sentiments were pretty much as follows; or, at all

events,

something like this was probably the upshot of his speech: "Tall Pygmies and

mighty little men! You and all of us have seen

what a public calamity has been brought to pass, and what an insult has

here

been offered to the majesty of our nation. Yonder lies AntŠus, our

great friend

and brother, slain, within our territory, by a miscreant who took him

at

disadvantage, and fought him (if fighting it can be called) in a way

that

neither man, nor Giant, nor Pygmy ever dreamed of fighting, until this

hour.

And, adding a grievous contumely to the wrong already done us, the

miscreant

has now fallen asleep as quietly as if nothing were to be dreaded from

our

wrath! It behooves you, fellow-countrymen, to consider in what aspect

we shall

stand before the world, and what will be the verdict of impartial

history,

should we suffer these accumulated outrages to go unavenged. "AntŠus was our

brother, born of that same beloved parent to whom

we owe the thews and sinews, as well as the courageous hearts, which

made him

proud of our relationship. He was our faithful ally, and fell fighting

as much

for our national rights and immunities as for his own personal ones. We

and our

forefathers have dwelt in friendship with him, and held affectionate

intercourse as man to man, through immemorial generations. You remember

how

often our entire people have reposed in his great shadow, and how our

little

ones have played at hide-and-seek in the tangles of his hair, and how

his

mighty footsteps have familiarly gone to and fro among us, and never

trodden

upon any of our toes. And there lies this dear brother Ś this sweet and

amiable

friend Ś this brave and faithful ally Ś -this virtuous Giant Ś this

blameless

and excellent AntŠus Ś dead! Dead! Silent! Powerless! A mere mountain

of clay!

Forgive my tears! Nay, I behold your own. Were we to drown the world

with them,

could the world blame us? "But to resume:

Shall we, my countrymen, suffer this wicked

stranger to depart unharmed, and triumph in his treacherous victory,

among

distant communities of the earth? Shall we not rather compel him to

leave his

bones here on our soil, by the side of our slain brother's bones? so

that,

while one skeleton shall remain as the everlasting monument of our

sorrow, the

other shall endure as long, exhibiting to the whole human race a

terrible

example of Pygmy vengeance! Such is the question. I put it to you in

full

confidence of a response that shall be worthy of our national

character, and

calculated to increase, rather than diminish, the glory which our

ancestors

have transmitted to us, and which we ourselves have proudly vindicated

in our

warfare with the cranes." The orator was here

interrupted by a burst of irrepressible enthusiasm;

every individual Pygmy crying out that the national honor must be

preserved at

all hazards. He bowed, and, making a gesture for silence, wound up his

harangue

in the following admirable manner: "It only remains for

us, then, to decide whether we shall carry on

the war in our national capacity Ś one united people against a common

enemy Ś or

whether some champion, famous in former fights, shall be selected to

defy the

slayer of our brother AntŠus to single combat. In the latter case,

though not

unconscious that there may be taller men among you, I hereby offer

myself for

that enviable duty. And believe me, dear countrymen, whether I live or

die, the

honor of this great country, and the fame bequeathed us by our heroic

progenitors, shall suffer no diminution in my hands. Never, while I can

wield

this sword, of which I now fling away the scabbard Ś never, never,

never, even

if the crimson hand that slew the great AntŠus shall lay me prostrate,

like

him, on the soil which I give my life to defend." So saying, this

valiant Pygmy drew out his weapon (which was terrible to

behold, being as long as the blade of a penknife), and sent the

scabbard

whirling over the heads of the multitude. His speech was followed by an

uproar

of applause, as its patriotism and self-devotion unquestionably

deserved; and

the shouts and clapping of hands would have been greatly prolonged, had

they

not been rendered quite inaudible by a deep respiration, vulgarly

called a

snore, from the sleeping Hercules. It was finally decided that the whole nation of Pygmies should set to work to destroy Hercules; not, be it understood, from any doubt that a single champion would be capable of putting him to the sword, but because he was a public enemy, and all were desirous of sharing in the glory of his defeat. There was a debate whether the national honor did not demand that a herald should be sent with a trumpet, to stand over the ear of Hercules, and after blowing a blast right into it, to defy him to the combat by formal proclamation. But two or three venerable and sagacious Pygmies, well versed in state affairs, gave it as their opinion that war already existed, and that it was their rightful privilege to take the enemy by surprise. Moreover, if awakened, and allowed to get upon his feet, Hercules might happen to do them a mischief before he could be beaten down again. For, as these sage counselors remarked, the stranger's club was really very big, and had rattled like a thunderbolt against the skull of AntŠus. So the Pygmies resolved to set aside all foolish punctilios, and assail their antagonist at once.  The enemy's

breath rushed

out of his nose in an obstreperous hurricane and whirlwind

Accordingly, all the

fighting men of the nation took their weapons, and

went boldly up to Hercules, who still lay fast asleep, little dreaming

of the

harm which the Pygmies meant to do him. A body of twenty thousand

archers

marched in front, with their little bows all ready, and the arrows on

the

string. The same number were ordered to clamber upon Hercules, some

with spades

to dig his eyes out, and others with bundles of hay, and all manner of

rubbish

with which they intended to plug up his mouth and nostrils, so that he

might

perish for lack of breath. These last, however, could by no means

perform their

appointed duty; inasmuch as the enemy's breath rushed out of his nose

in an

obstreperous hurricane and whirlwind, which blew the Pygmies away as

fast as

they came nigh. It was found necessary, therefore, to hit upon some

other

method of carrying on the war. After holding a

council, the captains ordered their troops to collect

sticks, straws, dry weeds, and whatever combustible stuff they could

find, and

make a pile of it, heaping it high around the head of Hercules. As a

great many

thousand Pygmies were employed in this task, they soon brought together

several

bushels of inflammatory matter, and raised so tall a heap, that,

mounting on

its summit, they were quite upon a level with the sleeper's face. The

archers,

meanwhile, were stationed within bow shot, with orders to let fly at

Hercules

the instant that he stirred. Everything being in readiness, a torch was

applied

to the pile, which immediately burst into flames, and soon waxed hot

enough to

roast the enemy, had he but chosen to lie still. A Pygmy, you know,

though so

very small, might set the world on fire, just as easily as a Giant

could; so

that this was certainly the very best way of dealing with their foe,

provided

they could have kept him quiet while the conflagration was going

forward. But no sooner did

Hercules begin to be scorched, than up he started,

with his hair in a red blaze. "What's all this?"

he cried, bewildered with sleep, and

staring about him as if he expected to see another Giant. At that moment the

twenty thousand archers twanged their bowstrings, and

the arrows came whizzing, like so many winged mosquitoes, right into

the face

of Hercules. But I doubt whether more than half a dozen of them

punctured the

skin, which was remarkably tough, as you know the skin of a hero has

good need

to be. "Villain!" shouted

all the Pygmies at once. "You have

killed the Giant AntŠus, our great brother, and the ally of our nation.

We

declare bloody war against you, and will slay you on the spot." Surprised at the

shrill piping of so many little voices, Hercules, after

putting out the conflagration of his hair, gazed all round about, but

could see

nothing. At last, however, looking narrowly on the ground, he espied

the

innumerable assemblage of Pygmies at his feet. He stooped down, and

taking up

the nearest one between his thumb and finger, set him on the palm of

his left

hand, and held him at a proper distance for examination. It chanced to

be the

very identical Pygmy who had spoken from the top of the toadstool, and

had

offered himself as a champion to meet Hercules in single combat. "What in the world,

my little fellow," ejaculated Hercules,

"may you be?" "I am your enemy,"

answered the valiant Pygmy, in his

mightiest squeak. "You have slain the enormous AntŠus, our brother by

the

mother's side, and for ages the faithful ally of our illustrious

nation. We are

determined to put you to death; and for my own part, I challenge you to

instant

battle, on equal ground." Hercules was so

tickled with the Pygmy's big words and warlike gestures,

that he burst into a great explosion of laughter, and almost dropped

the poor

little mite of a creature off the palm of his hand, through the ecstasy

and

convulsion of his merriment. "Upon my word,"

cried he, "I thought I had seen wonders

before to-day Ś hydras with nine heads, stags with golden horns,

six-legged

men, three-headed dogs, giants with furnaces in their stomachs, and

nobody

knows what besides. But here, on the palm of my hand, stands a wonder

that outdoes

them all! Your body, my little friend, is about the size of an ordinary

man's

finger. Pray, how big may your soul be?" "As big as your

own!" said the Pygmy. Hercules was touched

with the little man's dauntless courage, and could

not help acknowledging such a brotherhood with him as one hero feels

for

another. "My good little

people," said he, making a low obeisance to

the grand nation, "not for all the world would I do an intentional

injury

to such brave fellows as you! Your hearts seem to me so exceedingly

great,

that, upon my honor, I marvel how your small bodies can contain them. I

sue for

peace, and, as a condition of it, will take five strides, and be out of

your

kingdom at the sixth. Good-bye. I shall pick my steps carefully, for

fear of

treading upon some fifty of you, without knowing it. Ha, ha, ha! Ho,

ho, ho!

For once, Hercules acknowledges himself vanquished." Some writers say, that Hercules gathered up the whole race of Pygmies in his lion's skin, and carried them home to Greece, for the children of King Eurystheus to play with. But this is a mistake. He left them, one and all, within their own territory, where, for aught I can tell, their descendants are alive to the present day, building their little houses, cultivating their little fields, spanking their little children, waging their little warfare with the cranes, doing their little business, whatever it may be, and reading their little histories of ancient times. In those histories, perhaps, it stands recorded, that, a great many centuries ago, the valiant Pygmies avenged the death of the Giant AntŠus by scaring away the mighty Hercules.

|