| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| The Minotaur. In the old city of

Trœzene, at the foot of a lofty mountain, there

lived, a very long time ago, a little boy named Theseus. His

grandfather, King

Pittheus, was the sovereign of that country, and was reckoned a very

wise man;

so that Theseus, being brought up in the royal palace, and being

naturally a

bright lad, could hardly fail of profiting by the old king's

instructions. His

mother's name was Æthra. As for his father, the boy had never seen him.

But,

from his earliest remembrance, Æthra used to go with little Theseus

into a

wood, and sit down upon a moss-grown rock, which was deeply sunken into

the

earth. Here she often talked with her son about his father, and said

that he

was called Ægeus, and that he was a great king, and ruled over Attica,

and

dwelt at Athens, which was as famous a city as any in the world.

Theseus was

very fond of hearing about King Ægeus, and often asked his good mother

Æthra

why he did not come and live with them at Trœzene. "Ah, my dear son,"

answered Æthra, with a sigh, "a

monarch has his people to take care of. The men and women over whom he

rules

are in the place of children to him; and he can seldom spare time to

love his

own children as other parents do. Your father will never be able to

leave his

kingdom for the sake of seeing his little boy." "Well, but, dear

mother," asked the boy, "why cannot I go

to this famous city of Athens, and tell King Ægeus that I am his son?" "That may happen by

and by," said Æthra. "Be patient, and

we shall see. You are not yet big and strong enough to set out on such

an

errand." "And how soon shall

I be strong enough?" Theseus persisted in

inquiring. "You are but a tiny

boy as yet," replied his mother. "See

if you can lift this rock on which we are sitting?" The little fellow

had a great opinion of his own strength. So, grasping

the rough protuberances of the rock, he tugged and toiled amain, and

got

himself quite out of breath, without being able to stir the heavy

stone. It

seemed to be rooted into the ground. No wonder he could not move it;

for it

would have taken all the force of a very strong man to lift it out of

its earthy

bed. His mother stood

looking on, with a sad kind of a smile on her lips and

in her eyes, to see the zealous and yet puny efforts of her little boy.

She

could not help being sorrowful at finding him already so impatient to

begin his

adventures in the world. "You see how it is,

my dear Theseus," said she. "You must

possess far more strength than now before I can trust you to go to

Athens, and

tell King Ægeus that you are his son. But when you can lift this rock,

and show

me what is hidden beneath it, I promise you my permission to depart." Often and often,

after this, did Theseus ask his mother whether it was

yet time for him to go to Athens; and still his mother pointed to the

rock, and

told him that, for years to come, he could not be strong enough to move

it. And

again and again the rosy-checked and curly-headed boy would tug and

strain at

the huge mass of stone, striving, child as he was, to do what a giant

could

hardly have done without taking both of his great hands to the task.

Meanwhile

the rock seemed to be sinking farther and farther into the ground. The

moss

grew over it thicker and thicker, until at last it looked almost like a

soft

green seat, with only a few gray knobs of granite peeping out. The

overhanging

trees, also, shed their brown leaves upon It, as often as the autumn

came; and

at its base grew ferns and wild flowers, some of which crept quite over

its

surface. To all appearance, the rock was as firmly fastened as any

other

portion of the earth's substance. But, difficult as

the matter looked, Theseus was now growing up to be

such a vigorous youth, that, in his own opinion, the time would quickly

come

when he might hope to get the upper hand of this ponderous lump of

stone. "Mother, I do

believe it has started!" cried he, after one of his

attempts. "The earth around it is certainly a little cracked!" "No, no, child!" his

mother hastily answered. "It is not

possible you can have moved it, such a boy as you still are!" Nor would she be

convinced, although Theseus showed her the place where

he fancied that the stem of a flower had been partly uprooted by the

movement

of the rock. But Æthra sighed, and looked disquieted; for, no doubt,

she began

to be conscious that her son was no longer a child, and that, in a

little while

hence, she must send him forth among the perils and troubles of the

world. It was not more than

a year afterwards when they were again sitting on

the moss-covered stone. Æthra had once more told him the oft-repeated

story of

his father, and how gladly he would receive Theseus at his stately

palace, and

how he would present him to his courtiers and the people, and tell them

that

here was the heir of his dominions. The eyes of Theseus glowed with

enthusiasm,

and he would hardly sit still to hear his mother speak. "Dear mother Æthra,"

he exclaimed, "I never felt half so

strong as now! I am no longer a child, nor a boy, nor a mere youth! I

feel

myself a man! It is now time to make one earnest trial to remove the

stone." "Ah, my dearest

Theseus," replied his mother "not yet!

not yet!" "Yes, mother," said

he, resolutely, "the time has

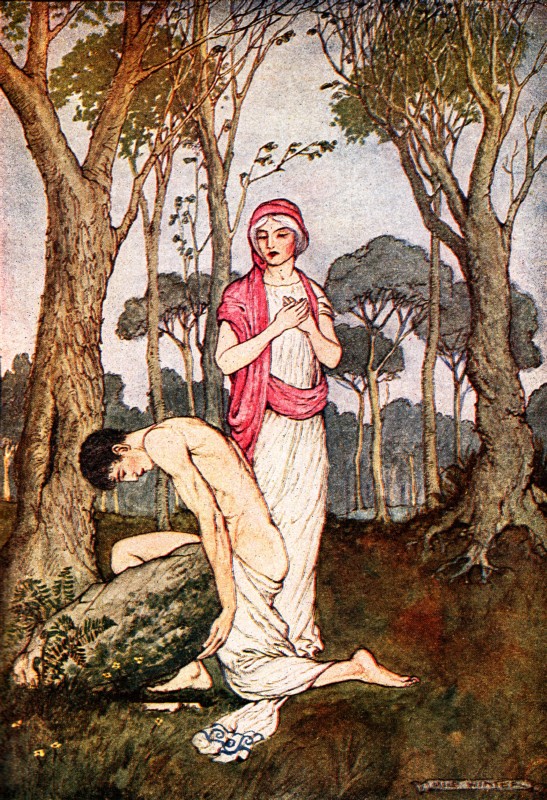

come!" Then Theseus bent himself in good earnest to the task, and strained every sinew, with manly strength and resolution. He put his whole brave heart into the effort. He wrestled with the big and sluggish stone, as if it had been a living enemy. He heaved, he lifted, he resolved now to succeed, or else to perish there, and let the rock be his monument forever! Æthra stood gazing at him, and clasped her hands, partly with a mother's pride, and partly with a mother's sorrow. The great rock stirred! Yes, it was raised slowly from the bedded moss and earth, uprooting the shrubs and flowers along with it, and was turned upon its side. Theseus had conquered!

The great rock

stirred!

While taking breath,

he looked joyfully at his mother, and she smiled

upon him through her tears. "Yes, Theseus," she

said, "the time has come, and you

must stay no longer at my side! See what King Ægeus, your royal father,

left

for you beneath the stone, when he lifted it in his mighty arms, and

laid it on

the spot whence you have now removed it." Theseus looked, and

saw that the rock had been placed over another slab

of stone, containing a cavity within it; so that it somewhat resembled

a

roughly-made chest or coffer, of which the upper mass had served as the

lid.

Within the cavity lay a sword, with a golden hilt, and a pair of

sandals. "That was your

father's sword," said Æthra, "and those

were his sandals. When he went to be king of Athens, he bade me treat

you as a

child until you should prove yourself a man by lifting this heavy

stone. That

task being accomplished, you are to put on his sandals, in order to

follow in

your father's footsteps, and to gird on his sword, so that you may

fight giants

and dragons, as King Ægeus did in his youth." "I will set out for

Athens this very day!" cried Theseus. But his mother

persuaded him to stay a day or two longer, while she got

ready some necessary articles for his journey. When his grandfather,

the wise

King Pittheus, heard that Theseus intended to present himself at his

father's

palace, he earnestly advised him to get on board of a vessel, and go by

sea;

because he might thus arrive within fifteen miles of Athens, without

either

fatigue or danger. "The roads are very

bad by land," quoth the venerable king;

"and they are terribly infested with robbers and monsters. A mere lad,

like Theseus, is not fit to be trusted on such a perilous journey, all

by

himself. No, no; let him go by sea." But when Theseus

heard of robbers and monsters, he pricked up his ears,

and was so much the more eager to take the road along which they were

to be met

with. On the third day, therefore, he bade a respectful farewell to his

grandfather, thanking him for all his kindness; and, after

affectionately

embracing his mother, he set forth with a good many of her tears

glistening on

his cheeks, and some, if the truth must be told, that had gushed out of

his own

eyes. But he let the sun and wind dry them, and walked stoutly on,

playing with

the golden hilt of his sword, and taking very manly strides in his

father's

sandals. I cannot stop to

tell you hardly any of the adventures that befell

Theseus on the road to Athens. It is enough to say, that he quite

cleared that

part of the country of the robbers about whom King Pittheus had been so

much

alarmed. One of these bad people was named Procrustes; and he was

indeed a

terrible fellow, and had an ugly way of making fun of the poor

travelers who

happened to fall into his clutches. In his cavern he had a bed, on

which, with

great pretense of hospitality, he invited his guests to lie down; but,

if they

happened to be shorter than the bed, this wicked villain stretched them

out by

main force; or, if they were too tall, he lopped off their heads or

feet, and

laughed at what he had done, as an excellent joke. Thus, however weary

a man

might be, he never liked to lie in the bed of Procrustes. Another of

these

robbers, named Scinis, must likewise have been a very great scoundrel.

He was

in the habit of flinging his victims off a high cliff into the sea;

and, in

order to give him exactly his deserts, Theseus tossed him off the very

same

place. But if you will believe me, the sea would not pollute itself by

receiving such a bad person into its bosom; neither would the earth,

having

once got rid of him, consent to take him back; so that, between the

cliff and

the sea, Scinis stuck fast in the air, which was forced to bear the

burden of

his naughtiness. After these

memorable deeds, Theseus heard of an enormous sow, which ran

wild, and was the terror of all the farmers round about; and, as he did

not

consider himself above doing any good thing that came in his way, he

killed

this monstrous creature, and gave the carcass to the poor people for

bacon. The

great sow had been an awful beast, while ramping about the woods and

fields,

but was a pleasant object enough when cut up into joints, and smoking

on I know

not how many dinner tables. Thus, by the time he

reached his journey's end, Theseus had done many

valiant feats with his father's golden-hilted sword, and had gained the

renown

of being one of the bravest young men of the day. His fame traveled

faster than

he did, and reached Athens before him. As he entered the city, he heard

the

inhabitants talking at the street corners, and saying that Hercules was

brave,

and Jason too, and Castor and Pollux likewise, but that Theseus, the

son of

their own king, would turn out as great a hero as the best of them.

Theseus

took longer strides on hearing this, and fancied himself sure of a

magnificent

reception at his father's court, since he came thither with Fame to

blow her

trumpet before him, and cry to King Ægeus, "Behold your son!" He little suspected,

innocent youth that he was, that here, in this very

Athens, where his father reigned, a greater danger awaited him than any

which

he had encountered on the road. Yet this was the truth. You must

understand

that the father of Theseus, though not very old in years, was almost

worn out

with the cares of government, and had thus grown aged before his time.

His nephews,

not expecting him to live a very great while, intended to get all the

power of

the kingdom into their own hands. But when they heard that Theseus had

arrived

in Athens, and learned what a gallant young man he was, they saw that

he would

not be at all the kind of a person to let them steal away his father's

crown

and scepter, which ought to be his own by right of inheritance. Thus

these

bad-hearted nephews of King Ægeus, who were the own cousins of Theseus,

at once

became his enemies. A still more dangerous enemy was Medea, the wicked

enchantress; for she was now the king's wife, and wanted to give the

kingdom to

her son Medus, instead of letting it be given to the son of Æthra, whom

she

hated. It so happened that

the king's nephews met Theseus, and found out who he

was, just as he reached the entrance of the royal palace. With all

their evil

designs against him, they pretended to be their cousin's best friends,

and

expressed great joy at making his acquaintance. They proposed to him

that he

should come into the king's presence as a stranger, in order to try

whether Ægeus

would discover in the young man's features any likeness either to

himself or

his mother Æthra, and thus recognize him for a son. Theseus consented;

for he

fancied that his father would know him in a moment, by the love that

was in his

heart. But, while he waited at the door, the nephews ran and told King

Ægeus

that a young man had arrived in Athens, who, to their certain

knowledge,

intended to put him to death, and get possession of his royal crown. "And he is now

waiting for admission to your majesty's

presence," added they. "Aha!" cried the old

king, on hearing this. "Why, he must

be a very wicked young fellow indeed! Pray, what would you advise me to

do with

him?" In reply to this

question, the wicked Medea put in her word. As I have

already told you, she was a famous enchantress. According to some

stories, she

was in the habit of boiling old people in a large caldron, under

pretense of

making them young again; but King Ægeus, I suppose, did not fancy such

an

uncomfortable way of growing young, or perhaps was contented to be old,

and

therefore would never let himself be popped into the caldron. If there

were

time to spare from more important matters, I should be glad to tell you

of Medea's

fiery chariot, drawn by winged dragons, in which the enchantress used

often to

take an airing among the clouds. This chariot, in fact, was the vehicle

that

first brought her to Athens, where she had done nothing but mischief

ever since

her arrival. But these and many other wonders must be left untold; and

it is

enough to say, that Medea, amongst a thousand other bad things, knew

how to

prepare a poison, that was instantly fatal to whomsoever might so much

as touch

it with his lips. So, when the king

asked what he should do with Theseus, this naughty

woman had an answer ready at her tongue's end. "Leave that to me,

please your majesty," she replied.

"Only admit this evil-minded young man to your presence, treat him

civilly, and invite him to drink a goblet of wine. Your majesty is well

aware

that I sometimes amuse myself by distilling very powerful medicines.

Here is

one of them in this small phial. As to what it is made of, that is one

of my

secrets of state. Do but let me put a single drop into the goblet, and

let the

young man taste it; and I will answer for it, he shall quite lay aside

the bad

designs with which he comes hither." As she said this,

Medea smiled; but, for all her smiling face, she meant

nothing less than to poison the poor innocent Theseus, before his

father's

eyes. And King Ægeus, like most other kings, thought any punishment

mild enough

for a person who was accused of plotting against his life. He therefore

made

little or no objection to Medea's scheme, and as soon as the poisonous

wine was

ready, gave orders that the young stranger should be admitted into his

presence. The goblet was set

on a table beside the king's throne; and a fly,

meaning just to sip a little from the brim, immediately tumbled into

it, dead.

Observing this, Medea looked round at the nephews, and smiled again. When Theseus was

ushered into the royal apartment, the only object that

he seemed to behold was the white-bearded old king. There he sat on his

magnificent throne, a dazzling crown on his head, and a scepter in his

hand.

His aspect was stately and majestic, although his years and infirmities

weighed

heavily upon him, as if each year were a lump of lead, and each

infirmity a

ponderous stone, and all were bundled up together, and laid upon his

weary

shoulders. The tears both of joy and sorrow sprang into the young man's

eyes;

for he thought how sad it was to see his dear father so infirm, and how

sweet

it would be to support him with his own youthful strength, and to cheer

him up

with the alacrity of his loving spirit. When a son takes a father into

his warm

heart it renews the old man's youth in a better way than by the heat of

Medea's

magic caldron. And this was what Theseus resolved to do. He could

scarcely wait

to see whether King Ægeus would recognize him, so eager was he to throw

himself

into his arms. Advancing to the

foot of the throne, he attempted to make a little

speech, which he had been thinking about, as he came up the stairs. But

he was

almost choked by a great many tender feelings that gushed out of his

heart and

swelled into his throat, all struggling to find utterance together. And

therefore, unless he could have laid his full, over-brimming heart into

the

king's hand, poor Theseus knew not what to do or say. The cunning Medea

observed what was passing in the young man's mind. She was more wicked

at that

moment than ever she had been before; for (and it makes me tremble to

tell you

of it) she did her worst to turn all this unspeakable love with which

Theseus

was agitated to his own ruin and destruction. "Does your majesty

see his confusion?" she whispered in the

king's ear. "He is so conscious of guilt, that he trembles and cannot

speak. The wretch lives too long! Quick! offer him the wine!" Now King Ægeus had

been gazing earnestly at the young stranger, as he

drew near the throne. There was something, he knew not what, either in

his

white brow, or in the fine expression of his mouth, or in his beautiful

and

tender eyes, that made him indistinctly feel as if he had seen this

youth

before; as if, indeed, he had trotted him on his knee when a baby, and

had

beheld him growing to be a stalwart man, while he himself grew old. But

Medea

guessed how the king felt, and would not suffer him to yield to these

natural

sensibilities; although they were the voice of his deepest heart,

telling him

as plainly as it could speak, that here was our dear son, and Æthra's

son,

coming to claim him for a father. The enchantress again whispered in

the king's

ear, and compelled him, by her witchcraft, to see everything under a

false

aspect. He made up his mind,

therefore, to let Theseus drink off the poisoned

wine. "Young man," said

he, "you are welcome! I am proud to

show hospitality to so heroic a youth. Do me the favor to drink the

contents of

this goblet. It is brimming over, as you see, with delicious wine, such

as I

bestow only on those who are worthy of it! None is more worthy to quaff

it than

yourself!" So saying, King

Ægeus took the golden goblet from the table, and was

about to offer it to Theseus. But, partly through his infirmities, and

partly

because it seemed so sad a thing to take away this young man's life.

however

wicked he might be, and partly, no doubt, because his heart was wiser

than his

head, and quaked within him at the thought of what he was going to do —

for all

these reasons, the king's hand trembled so much that a great deal of

the wine

slopped over. In order to strengthen his purpose, and fearing lest the

whole of

the precious poison should be wasted, one of his nephews now whispered

to him: "Has your Majesty

any doubt of this stranger's guilt? This is the

very sword with which he meant to slay you. How sharp, and bright, and

terrible

it is! Quick! — let him taste the wine; or perhaps he may do the deed

even

yet." At these words,

Ægeus drove every thought and feeling out of his breast,

except the one idea of how justly the young man deserved to be put to

death. He

sat erect on his throne, and held out the goblet of wine with a steady

hand,

and bent on Theseus a frown of kingly severity; for, after all, he had

too

noble a spirit to murder even a treacherous enemy with a deceitful

smile upon

his face. "Drink!" said he, in

the stern tone with which he was wont to

condemn a criminal to be beheaded. "You have well deserved of me such

wine

as this!" Theseus held out his

hand to take the wine. But, before he touched it,

King Ægeus trembled again. His eyes had fallen on the gold-hilted sword

that

hung at the young man's side. He drew back the goblet. "That sword!" he

exclaimed: "how came you by it?" "It was my father's

sword," replied Theseus, with a tremulous

voice. "These were his sandals. My dear mother (her name is Æthra) told

me

his story while I was yet a little child. But it is only a month since

I grew

strong enough to lift the heavy stone, and take the sword and sandals

from

beneath it, and come to Athens to seek my father." "My son! my son!"

cried King Ægeus, flinging away the fatal

goblet, and tottering down from the throne to fall into the arms of

Theseus.

"Yes, these are Æthra's eyes. It is my son." I have quite

forgotten what became of the king's nephews. But when the

wicked Medea saw this new turn of affairs, she hurried out of the room,

and

going to her private chamber, lost no time to setting her enchantments

to work.

In a few moments, she heard a great noise of hissing snakes outside of

the

chamber window; and behold! there was her fiery chariot, and four huge

winged

serpents, wriggling and twisting in the air, flourishing their tails

higher

than the top of the palace, and all ready to set off on an ærial

journey. Medea

staid only long enough to take her son with her, and to steal the crown

jewels,

together with the king's best robes, and whatever other valuable things

she

could lay hands on; and getting into the chariot, she whipped up the

snakes,

and ascended high over the city. The king, hearing

the hiss of the serpents, scrambled as fast as he

could to the window, and bawled out to the abominable enchantress never

to come

back. The whole people of Athens, too, who had run out of doors to see

this

wonderful spectacle, set up a shout of joy at the prospect of getting

rid of

her. Medea, almost bursting with rage, uttered precisely such a hiss as

one of

her own snakes, only ten times more venomous and spiteful; and glaring

fiercely

out of the blaze of the chariot, she shook her hands over the multitude

below,

as if she were scattering a million of curses among them. In so doing,

however,

she unintentionally let fall about five hundred diamonds of the first

water,

together with a thousand great pearls, and two thousand emeralds,

rubies,

sapphires, opals, and topazes, to which she had helped herself out of

the

king's strong box. All these came pelting down, like a shower of

many-colored

hailstones, upon the heads of grown people and children, who forthwith

gathered

them up, and carried them back to the palace. But King Ægeus told them

that

they were welcome to the whole, and to twice as many more, if he had

them, for

the sake of his delight at finding his son, and losing the wicked

Medea. And,

indeed, if you had seen how hateful was her last look, as the flaming

chariot

flew upward, you would not have wondered that both king and people

should think

her departure a good riddance. And now Prince

Theseus was taken into great favor by his royal father.

The old king was never weary of having him sit beside him on his throne

(which

was quite wide enough for two), and of hearing him tell about his dear

mother,

and his childhood, and his many boyish efforts to lift the ponderous

stone.

Theseus, however, was much too brave and active a young man to be

willing to

spend all his time in relating things which had already happened. His

ambition

was to perform other and more heroic deeds, which should be better

worth

telling in prose and verse. Nor had he been long in Athens before he

caught and

chained a terrible mad bull, and made a public show of him, greatly to

the

wonder and admiration of good King Ægeus and his subjects. But pretty

soon, he

undertook an affair that made all his foregone adventures seem like

mere boy's

play. The occasion of it was as follows: One morning, when

Prince Theseus awoke, he fancied that he must have had

a very sorrowful dream, and that it was still running in his mind, even

now

that his eyes were opened. For it appeared as if the air was full of a

melancholy wail; and when he listened more attentively, he could hear

sobs, and

groans, and screams of woe, mingled with deep, quiet sighs, which came

from the

king's palace, and from the streets, and from the temples, and from

every habitation

in the city. And all these mournful noises, issuing out of thousands of

separate hearts, united themselves into one great sound of affliction,

which

had startled Theseus from slumber. He put on his clothes as quickly as

he could

(not forgetting his sandals and gold-hilted sword), and, hastening to

the king,

inquired what it all meant. "Alas! my son,"

quoth King Ægeus, heaving a long sigh,

"here is a very lamentable matter in hand! This is the wofulest

anniversary in the whole year. It is the day when we annually draw lots

to see

which of the youths and maids of Athens shall go to be devoured by the

horrible

Minotaur!" "The Minotaur!"

exclaimed Prince Theseus; and like a brave

young prince as he was, he put his hand to the hilt of his sword. "What

kind of a monster may that be? Is it not possible, at the risk of one's

life,

to slay him?" But King Ægeus shook

his venerable head, and to convince Theseus that it

was quite a hopeless case, he gave him an explanation of the whole

affair. It

seems that in the island of Crete there lived a certain dreadful

monster,

called a Minotaur, which was shaped partly like a man and partly like a

bull,

and was altogether such a hideous sort of a creature that it is really

disagreeable to think of him. If he were suffered to exist at all, it

should

have been on some desert island, or in the duskiness of some deep

cavern, where

nobody would ever be tormented by his abominable aspect. But King

Minos, who

reigned over Crete, laid out a vast deal of money in building a

habitation for

the Minotaur, and took great care of his health and comfort, merely for

mischief's sake. A few years before this time, there had been a war

between the

city of Athens and the island of Crete, in which the Athenians were

beaten, and

compelled to beg for peace. No peace could they obtain, however, except

on

condition that they should send seven young men and seven maidens,

every year,

to be devoured by the pet monster of the cruel King Minos. For three

years

past, this grievous calamity had been borne. And the sobs, and groans,

and

shrieks, with which the city was now filled, were caused by the

people's woe,

because the fatal day had come again, when the fourteen victims were to

be

chosen by lot; and the old people feared lest their sons or daughters

might be

taken, and the youths and damsels dreaded lest they themselves might be

destined to glut the ravenous maw of that detestable man-brute. But when Theseus

heard the story, he straightened himself up, so that he

seemed taller than ever before; and as for his face it was indignant,

despiteful, bold, tender, and compassionate, all in one look. "Let the people of

Athens this year draw lots for only six young

men, instead of seven," said he, "I will myself be the seventh; and

let the Minotaur devour me if he can!" "O my dear son,"

cried King Ægeus, "why should you expose

yourself to this horrible fate? You are a royal prince, and have a

right to

hold yourself above the destinies of common men." "It is because I am

a prince, your son, and the rightful heir of

your kingdom, that I freely take upon me the calamity of your

subjects,"

answered Theseus, "And you, my father, being king over these people,

and

answerable to Heaven for their welfare, are bound to sacrifice what is

dearest

to you, rather than that the son or daughter of the poorest citizen

should come

to any harm." The old king shed

tears, and besought Theseus not to leave him desolate

in his old age, more especially as he had but just begun to know the

happiness

of possessing a good and valiant son. Theseus, however, felt that he

was in the

right, and therefore would not give up his resolution. But he assured

his

father that he did not intend to be eaten up, unresistingly, like a

sheep, and

that, if the Minotaur devoured him, it should not be without a battle

for his

dinner. And finally, since he could not help it, King Ægeus consented

to let

him go. So a vessel was got ready, and rigged with black sails; and

Theseus,

with six other young men, and seven tender and beautiful damsels, came

down to

the harbor to embark. A sorrowful multitude accompanied them to the

shore.

There was the poor old king, too, leaning on his son's arm, and looking

as if

his single heart held all the grief of Athens. Just as Prince

Theseus was going on board, his father bethought himself

of one last word to say. "My beloved son,"

said he, grasping the Prince's hand,

"you observe that the sails of this vessel are black; as indeed they

ought

to be, since it goes upon a voyage of sorrow and despair. Now, being

weighed

down with infirmities, I know not whether I can survive till the vessel

shall

return. But, as long as I do live, I shall creep daily to the top of

yonder

cliff, to watch if there be a sail upon the sea. And, dearest Theseus,

if by

some happy chance, you should escape the jaws of the Minotaur, then

tear down

those dismal sails, and hoist others that shall be bright as the

sunshine.

Beholding them on the horizon, myself and all the people will know that

you are

coming back victorious, and will welcome you with such a festal uproar

as

Athens never heard before." Theseus promised

that he would do so. Then going on board, the mariners

trimmed the vessel's black sails to the wind, which blew faintly off

the shore,

being pretty much made up of the sighs that everybody kept pouring

forth on

this melancholy occasion. But by and by, when they had got fairly out

to sea,

there came a stiff breeze from the north-west, and drove them along as

merrily

over the white-capped waves as if they had been going on the most

delightful

errand imaginable. And though it was a sad business enough, I rather

question

whether fourteen young people, without any old persons to keep them in

order,

could continue to spend the whole time of the voyage in being

miserable. There

had been some few dances upon the undulating deck, I suspect, and some

hearty

bursts of laughter, and other such unseasonable merriment among the

victims,

before the high blue mountains of Crete began to show themselves among

the

far-off clouds. That sight, to be sure, made them all very grave again.

Theseus stood among

the sailors, gazing eagerly towards the land;

although, as yet, it seemed hardly more substantial than the clouds,

amidst

which the mountains were looming up. Once or twice, he fancied that he

saw a

glare of some bright object, a long way off, flinging a gleam across

the waves. "Did you see that

flash of light?" he inquired of the master

of the vessel. "No, prince; but I

have seen it before," answered the master.

"It came from Talus, I suppose." As the breeze came

fresher just then, the master was busy with trimming

his sails, and had no more time to answer questions. But while the

vessel flew

faster and faster towards Crete, Theseus was astonished to behold a

human

figure, gigantic in size, which appeared to be striding, with a

measured

movement, along the margin of the island. It stepped from cliff to

cliff, and

sometimes from one headland to another, while the sea foamed and

thundered on

the shore beneath, and dashed its jets of spray over the giant's feet.

What was

still more remarkable, whenever the sun shone on this huge figure, it

flickered

and glimmered; its vast countenance, too, had a metallic lustre, and

threw

great flashes of splendor through the air. The folds of its garments,

moreover,

instead of waving in the wind, fell heavily over its limbs, as if woven

of some

kind of metal. The nigher the

vessel came, the more Theseus wondered what this immense

giant could be, and whether it actually had life or no. For, though it

walked,

and made other lifelike motions, there yet was a kind of jerk in its

gait,

which, together with its brazen aspect, caused the young prince to

suspect that

it was no true giant, but only a wonderful piece of machinery. The

figure

looked all the more terrible because it carried an enormous brass club

on its

shoulder. "What is this

wonder?" Theseus asked of the master of the

vessel, who was now at leisure to answer him. "It is Talus, the

Man of Brass," said the master. "And is he a live

giant, or a brazen image?" asked Theseus. "That, truly,"

replied the master, "is the point which

has always perplexed me. Some say, indeed, that this Talus was hammered

out for

King Minos by Vulcan himself, the skilfullest of all workers in metal.

But who

ever saw a brazen image that had sense enough to walk round an island

three

times a day, as this giant walks round the island of Crete, challenging

every

vessel that comes nigh the shore? And, on the other hand, what living

thing,

unless his sinews were made of brass, would not be weary of marching

eighteen

hundred miles in the twenty-four hours, as Talus does, without ever

sitting

down to rest? He is a puzzler, take him how you will." Still the vessel

went bounding onward; and now Theseus could hear the

brazen clangor of the giant's footsteps, as he trod heavily upon the

sea-beaten

rocks, some of which were seen to crack and crumble into the foaming

waves

beneath his weight. As they approached the entrance of the port, the

giant

straddled clear across it, with a foot firmly planted on each headland,

and

uplifting his club to such a height that its butt-end was hidden in the

cloud,

he stood in that formidable posture, with the sun gleaming all over his

metallic surface. There seemed nothing else to be expected but that,

the next

moment, he would fetch his great club down, slam bang, and smash the

vessel

into a thousand pieces, without heeding how many innocent people he

might

destroy; for there is seldom any mercy in a giant, you know, and quite

as

little in a piece of brass clockwork. But just when Theseus and his

companions

thought the blow was coming, the brazen lips unclosed themselves, and

the

figure spoke. "Whence come you,

strangers?" And when the ringing

voice ceased, there was just such a reverberation

as you may have heard within a great church bell, for a moment or two

after the

stroke of the hammer. "From Athens!"

shouted the master in reply. "On what errand?"

thundered the Man of Brass. And he whirled his

club aloft more threateningly than ever, as if he

were about to smite them with a thunderstroke right amidships, because

Athens,

so little while ago, had been at war with Crete. "We bring the seven

youths and the seven maidens," answered

the master, "to be devoured by the Minotaur!" "Pass!" cried the

brazen giant. That one loud word

rolled all about the sky, while again there was a

booming reverberation within the figure's breast. The vessel glided

between the

headlands of the port, and the giant resumed his march. In a few

moments, this

wondrous sentinel was far away, flashing in the distant sunshine, and

revolving

with immense strides round the island of Crete, as it was his

never-ceasing

task to do. No sooner had they

entered the harbor than a party of the guards of King

Minos came down to the water side, and took charge of the fourteen

young men

and damsels. Surrounded by these armed warriors, Prince Theseus and his

companions were led to the king's palace, and ushered into his

presence. Now,

Minos was a stern and pitiless king. If the figure that guarded Crete

was made

of brass, then the monarch, who ruled over it, might be thought to have

a still

harder metal in his breast, and might have been called a man of iron.

He bent

his shaggy brows upon the poor Athenian victims. Any other mortal,

beholding

their fresh and tender beauty, and their innocent looks, would have

felt

himself sitting on thorns until he had made every soul of them happy by

bidding

them go free as the summer wind. But this immitigable Minos cared only

to

examine whether they were plump enough to satisfy the Minotaur's

appetite. For

my part, I wish he himself had been the only victim; and the monster

would have

found him a pretty tough one. One after another,

King Minos called these pale, frightened youths and

sobbing maidens to his footstool, gave them each a poke in the ribs

with his

sceptre (to try whether they were in good flesh or no), and dismissed

them with

a nod to his guards. But when his eyes rested on Theseus, the king

looked at

him more attentively, because his face was calm and brave. "Young man," asked

he, with his stern voice, "are you not

appalled at the certainty of being devoured by this terrible Minotaur?"

"I have offered my

life in a good cause," answered Theseus,

"and therefore I give it freely and gladly. But thou, King Minos, art

thou

not thyself appalled, who, year after year, hast perpetrated this

dreadful

wrong, by giving seven innocent youths and as many maidens to be

devoured by a

monster? Dost thou not tremble, wicked king, to turn shine eyes inward

on shine

own heart? Sitting there on thy golden throne, and in thy robes of

majesty, I

tell thee to thy face, King Minos, thou art a more hideous monster than

the

Minotaur himself!" "Aha! do you think

me so?" cried the king, laughing in his

cruel way. "To-morrow, at breakfast time, you shall have an opportunity

of

judging which is the greater monster, the Minotaur or the king! Take

them away,

guards; and let this free-spoken youth be the Minotaur's first morsel."

Near the king's

throne (though I had no time to tell you so before)

stood his daughter Ariadne. She was a beautiful and tender-hearted

maiden, and

looked at these poor doomed captives with very different feelings from

those of

the iron-breasted King Minos. She really wept indeed, at the idea of

how much

human happiness would be needlessly thrown away, by giving so many

young

people, in the first bloom and rose blossom of their lives, to be eaten

up by a

creature who, no doubt, would have preferred a fat ox, or even a large

pig, to

the plumpest of them. And when she beheld the brave, spirited figure of

Prince

Theseus bearing himself so calmly in his terrible peril, she grew a

hundred

times more pitiful than before. As the guards were taking him away, she

flung

herself at the king's feet, and besought him to set all the captives

free, and

especially this one young man. "Peace, foolish

girl!" answered King Minos. "What hast thou to

do with an affair like this? It is a matter of

state policy, and therefore quite beyond thy weak comprehension. Go

water thy

flowers, and think no more of these Athenian caitiffs, whom the

Minotaur shall

as certainly eat up for breakfast as I will eat a partridge for my

supper." So saying, the king

looked cruel enough to devour Theseus and all the

rest of the captives himself, had there been no Minotaur to save him

the

trouble. As he would hear not another word in their favor, the

prisoners were

now led away, and clapped into a dungeon, where the jailer advised them

to go

to sleep as soon as possible, because the Minotaur was in the habit of

calling

for breakfast early. The seven maidens and six of the young men soon

sobbed

themselves to slumber. But Theseus was not like them. He felt conscious

that he

was wiser, and braver, and stronger than his companions, and that

therefore he

had the responsibility of all their lives upon him, and must consider

whether

there was no way to save them, even in this last extremity. So he kept

himself

awake, and paced to and fro across the gloomy dungeon in which they

were shut

up. Just before

midnight, the door was softly unbarred, and the gentle

Ariadne showed herself, with a torch in her hand. "Are you awake,

Prince Theseus?" she whispered. "Yes," answered

Theseus. "With so little time to live, I

do not choose to waste any of it in sleep." "Then follow me,"

said Ariadne, "and tread softly." What had become of

the jailer and the guards, Theseus never knew. But,

however that might be, Ariadne opened all the doors, and led him forth

from the

darksome prison into the pleasant moonlight. "Theseus," said the

maiden, "you can now get on board

your vessel, and sail away for Athens." "No," answered the

young man; "I will never leave Crete

unless I can first slay the Minotaur, and save my poor companions, and

deliver

Athens from this cruel tribute." "I knew that this

would be your resolution," said Ariadne.

"Come, then, with me, brave Theseus. Here is your own sword, which the

guards deprived you of. You will need it; and pray Heaven you may use

it

well." Then she led Theseus

along by the hand until they came to a dark,

shadowy grove, where the moonlight wasted itself on the tops of the

trees,

without shedding hardly so much as a glimmering beam upon their

pathway. After

going a good way through this obscurity, they reached a high marble

wall, which

was overgrown with creeping plants, that made it shaggy with their

verdure. The

wall seemed to have no door, nor any windows, but rose up, lofty, and

massive,

and mysterious, and was neither to be clambered over, nor, as far as

Theseus

could perceive, to be passed through. Nevertheless, Ariadne did but

press one

of her soft little fingers against a particular block of marble and,

though it

looked as solid as any other part of the wall, it yielded to her touch,

disclosing an entrance just wide enough to admit them They crept

through, and the

marble stone swung back into its place. "We are now," said

Ariadne, "in the famous labyrinth

which Dædalus built before he made himself a pair of wings, and flew

away from

our island like a bird. That Dædalus was a very cunning workman; but of

all his

artful contrivances, this labyrinth is the most wondrous. Were we to

take but a

few steps from the doorway, we might wander about all our lifetime, and

never

find it again. Yet in the very center of this labyrinth is the

Minotaur; and,

Theseus, you must go thither to seek him." "But how shall I

ever find him," asked Theseus, "if the

labyrinth so bewilders me as you say it will?" Just as he spoke,

they heard a rough and very disagreeable roar, which

greatly resembled the lowing of a fierce bull, but yet had some sort of

sound

like the human voice. Theseus even fancied a rude articulation in it,

as if the

creature that uttered it were trying to shape his hoarse breath into

words. It

was at some distance, however, and he really could not tell whether it

sounded

most like a bull's roar or a man's harsh voice. "That is the

Minotaur's noise," whispered Ariadne, closely

grasping the hand of Theseus, and pressing one of her own hands to her

heart,

which was all in a tremble. "You must follow that sound through the

windings of the labyrinth, and, by and by, you will find him. Stay!

take the

end of this silken string; I will hold the other end; and then, if you

win the

victory, it will lead you again to this spot. Farewell, brave Theseus."

So the young man

took the end of the silken string in his left hand, and

his gold-hilted sword, ready drawn from its scabbard, in the other, and

trod

boldly into the inscrutable labyrinth. How this labyrinth was built is

more

than I can tell you. But so cunningly contrived a mizmaze was never

seen in the

world, before nor since. There can be nothing else so intricate, unless

it were

the brain of a man like Dædalus, who planned it, or the heart of any

ordinary

man; which last, to be sure, is ten times as great a mystery as the

labyrinth

of Crete. Theseus had not taken five steps before he lost sight of

Ariadne; and

in five more his head was growing dizzy. But still he went on, now

creeping

through a low arch, now ascending a flight of steps, now in one crooked

passage

and now in another, with here a door opening before him, and there one

banging

behind, until it really seemed as if the walls spun round, and whirled

him

round along with them. And all the while, through these hollow avenues,

now

nearer, now farther off again, resounded the cry of the Minotaur; and

the sound

was so fierce, so cruel, so ugly, so like a bull's roar, and withal so

like a

human voice, and yet like neither of them, that the brave heart of

Theseus grew

sterner and angrier at every step; for he felt it an insult to the moon

and

sky, and to our affectionate and simple Mother Earth, that such a

monster

should have the audacity to exist. As he passed onward,

the clouds gathered over the moon, and the

labyrinth grew so dusky that Theseus could no longer discern the

bewilderment

through which he was passing. He would have left quite lost, and

utterly

hopeless of ever again walking in a straight path, if, every little

while, he

had not been conscious of a gentle twitch at the silken cord. Then he

knew that

the tender-hearted Ariadne was still holding the other end, and that

she was

fearing for him, and hoping for him, and giving him just as much of her

sympathy as if she were close by his side. O, indeed, I can assure you,

there

was a vast deal of human sympathy running along that slender thread of

silk.

But still he followed the dreadful roar of the Minotaur, which now grew

louder

and louder, and finally so very loud that Theseus fully expected to

come close

upon him, at every new zizgag and wriggle of the path. And at last, in

an open

space, at the very center of the labyrinth, he did discern the hideous

creature. Sure enough, what an

ugly monster it was! Only his horned head belonged

to a bull; and yet, somehow or other, he looked like a bull all over,

preposterously waddling on his hind legs; or, if you happened to view

him in

another way, he seemed wholly a man, and all the more monstrous for

being so.

And there he was, the wretched thing, with no society, no companion, no

kind of

a mate, living only to do mischief, and incapable of knowing what

affection

means. Theseus hated him, and shuddered at him, and yet could not but

be

sensible of some sort of pity; and all the more, the uglier and more

detestable

the creature was. For he kept striding to and fro, in a solitary frenzy

of

rage, continually emitting a hoarse roar, which was oddly mixed up with

half-shaped words; and, after listening a while, Theseus understood

that the

Minotaur was saying to himself how miserable he was, and how hungry,

and how he

hated everybody, and how he longed to eat up the human race alive. Ah! the bull-headed

villain! And O, my good little people, you will

perhaps see, one of these days, as I do now, that every human being who

suffers

any thing evil to get into his nature, or to remain there, is a kind of

Minotaur, an enemy of his fellow-creatures, and separated from all good

companionship, as this poor monster was. Was Theseus afraid?

By no means, my dear auditors. What! a hero like

Theseus afraid, Not had the Minotaur had twenty bull-heads instead of

one. Bold

as he was, however, I rather fancy that it strengthened his valiant

heart, just

at this crisis, to feel a tremulous twitch at the silken cord, which he

was

still holding in his left hand. It was as if Ariadne were giving him

all her

might and courage; and much as he already had, and little as she had to

give,

it made his own seem twice as much. And to confess the honest truth, he

needed

the whole; for now the Minotaur, turning suddenly about, caught sight

of

Theseus, and instantly lowered his horribly sharp horns, exactly as a

mad bull does

when he means to rush against an enemy. At the same time, he belched

forth a

tremendous roar, in which there was something like the words of human

language,

but all disjointed and shaken to pieces by passing through the gullet

of a

miserably enraged brute. Theseus could only

guess what the creature intended to say, and that

rather by his gestures than his words; for the Minotaur's horns were

sharper

than his wits, and of a great deal more service to him than his tongue.

But

probably this was the sense of what he uttered: "Ah, wretch of a

human being! I'll stick my horns through you, and

toss you fifty feet high, and eat you up the moment you come down." "Come on, then, and

try it!" was all that Theseus deigned to

reply; for he was far too magnanimous to assault his enemy with

insolent

language. Without more words

on either side, there ensued the most awful fight

between Theseus and the Minotaur that ever happened beneath the sun or

moon. I

really know not how it might have turned out, if the monster, in his

first

headlong rush against Theseus, had not missed him, by a hair's breadth,

and

broken one of his horns short off against the stone wall. On this

mishap, he

bellowed so intolerably that a part of the labyrinth tumbled down, and

all the

inhabitants of Crete mistook the noise for an uncommonly heavy thunder

storm.

Smarting with the pain, he galloped around the open space in so

ridiculous a

way that Theseus laughed at it, long afterwards, though not precisely

at the

moment. After this, the two antagonists stood valiantly up to one

another, and

fought, sword to horn, for a long while. At last, the Minotaur made a

run at

Theseus, grazed his left side with his horn, and flung him down; and

thinking that

he had stabbed him to the heart, he cut a great caper in the air,

opened his

bull mouth from ear to ear, and prepared to snap his head off. But

Theseus by

this time had leaped up, and caught the monster off his guard. Fetching

a sword

stroke at him with all his force, he hit him fair upon the neck, and

made his

bull head skip six yards from his human body, which fell down flat upon

the

ground. So now the battle

was ended. Immediately the moon shone out as brightly

as if all the troubles of the world, and all the wickedness and the

ugliness

that infest human life, were past and gone forever. And Theseus, as he

leaned

on his sword, taking breath, felt another twitch of the silken cord;

for all

through the terrible encounter, he had held it fast in his left hand.

Eager to

let Ariadne know of his success, he followed the guidance of the

thread, and

soon found himself at the entrance of the labyrinth. "Thou hast slain the

monster," cried Ariadne, clasping her

hands. "Thanks to thee,

dear Ariadne," answered Theseus, "I

return victorious." "Then," said

Ariadne, "we must quickly summon thy

friends, and get them and thyself on board the vessel before dawn. If

morning

finds thee here, my father will avenge the Minotaur." To make my story

short, the poor captives were awakened, and, hardly

knowing whether it was not a joyful dream, were told of what Theseus

had done,

and that they must set sail for Athens before daybreak. Hastening down

to the

vessel, they all clambered on board, except Prince Theseus, who

lingered behind

them on the strand, holding Ariadne's hand clasped in his own. "Dear maiden," said

he, "thou wilt surely go with us.

Thou art too gentle and sweet a child for such an iron-hearted father

as King

Minos. He cares no more for thee than a granite rock cares for the

little

flower that grows in one of its crevices. But my father, King Ægeus,

and my

dear mother, Æthra, and all the fathers and mothers in Athens, and all

the sons

and daughters too, will love and honor thee as their benefactress. Come

with us,

then; for King Minos will be very angry when he knows what thou hast

done." Now, some low-minded

people, who pretend to tell the story of Theseus

and Ariadne, have the face to say that this royal and honorable maiden

did

really flee away, under cover of the night, with the young stranger

whose life

she had preserved. They say, too, that Prince Theseus (who would have

died

sooner than wrong the meanest creature in the world) ungratefully

deserted

Ariadne, on a solitary island, where the vessel touched on its voyage

to

Athens. But, had the noble Theseus heard these falsehoods, he would

have served

their slanderous authors as he served the Minotaur! Here is what

Ariadne

answered, when the brave prince of Athens besought her to accompany

him: "No, Theseus," the

maiden said, pressing his hand, and then

drawing back a step or two, "I cannot go with you. My father is old,

and

has nobody but myself to love him. Hard as you think his heart is, it

would

break to lose me. At first, King Minos will be angry; but he will soon

forgive

his only child; and, by and by, he will rejoice, I know, that no more

youths

and maidens must come from Athens to be devoured by the Minotaur. I

have saved

you, Theseus, as much for my father's sake as for your own. Farewell!

Heaven bless

you!" All this was so

true, and so maiden-like, and was spoken with so sweet a

dignity, that Theseus would have blushed to urge her any longer.

Nothing

remained for him, therefore, but to bid Ariadne an affectionate

farewell, and

to go on board the vessel, and set sail. In a few moments the

white foam was boiling up before their prow, as

Prince Theseus and his companions sailed out of the harbor, with a

whistling

breeze behind them. Talus, the brazen giant, on his never-ceasing

sentinel's

march, happened to be approaching that part of the coast; and they saw

him, by

the glimmering of the moonbeams on his polished surface, while he was

yet a

great way off. As the figure moved like clockwork, however, and could

neither

hasten his enormous strides nor retard them, he arrived at the port

when they

were just beyond the reach of his club. Nevertheless, straddling from

headland

to headland, as his custom was, Talus attempted to strike a blow at the

vessel,

and, overreaching himself, tumbled at full length into the sea, which

splashed

high over his gigantic shape, as when an iceberg turns a somerset.

There he

lies yet; and whoever desires to enrich himself by means of brass had

better go

thither with a diving bell, and fish up Talus. On the homeward voyage, the fourteen youths and damsels were in excellent spirits, as you will easily suppose. They spent most of their time in dancing, unless when the sidelong breeze made the deck slope too much. In due season, they came within sight of the coast of Attica, which was their native country. But here, I am grieved to tell you, happened a sad misfortune.  They never

once thought

whether their sails were black, white, or rainbow colored

You will remember

(what Theseus unfortunately forgot) that his father,

King Ægeus, had enjoined it upon him to hoist sunshiny sails, instead

of black

ones, in case he should overcome the Minotaur, and return victorious.

In the

joy of their success, however, and amidst the sports, dancing, and

other

merriment, with which these young folks wore away the time, they never

once

thought whether their sails were black, white, or rainbow colored, and,

indeed,

left it entirely to the mariners whether they had any sails at all.

Thus the

vessel returned, like a raven, with the same sable wings that had

wafted her

away. But poor King Ægeus, day after day, infirm as he was, had

clambered to

the summit of a cliff that overhung the sea, and there sat watching for

Prince

Theseus, homeward bound; and no sooner did he behold the fatal

blackness of the

sails, than he concluded that his dear son, whom he loved so much, and

felt so

proud of, had been eaten by the Minotaur. He could not bear the thought

of

living any longer; so, first flinging his crown and sceptre into the

sea

(useless baubles that they were to him now), King Ægeus merely stooped

forward,

and fell headlong over the cliff, and was drowned, poor soul, in the

waves that

foamed at its base! This was melancholy news for Prince Theseus, who, when he stepped ashore, found himself king of all the country, whether he would or no; and such a turn of fortune was enough to make any young man feel very much out of spirits. However, he sent for his dear mother to Athens, and, by taking her advice in matters of state, became a very excellent monarch, and was greatly beloved by his people. |