| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

XXIV. THE SHIPS OF MAlNE.

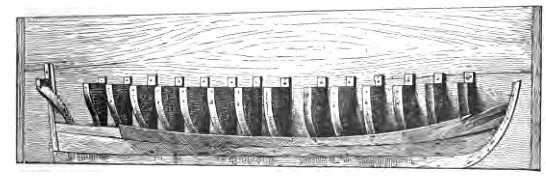

THE Flying Scud, acknowledged to be the fastest clipper the world has ever seen, was a Maine vessel. On one day—and this performance is recorded in the government office at Washington—she made nearly five hundred miles, a speed that almost matches that of an Atlantic "greyhound" of this day. The Scud was built at Damariscotta, by Metcalf & Co., in 1859 or 1860, and was intended for the tea trade, at a time when it meant a small fortune to bring to port the first of the new crop. The Dash was built at Porters Landing, by the Porter brothers, John and Seward, merchants doing business in Portland. The record of this little craft was, as her papers remain to show, one which even fancy has not improved upon, although vessels of this character have been a favorite with novelists. The Ariel of Cooper was not the equal of this Maine craft. The Dash was unique in her inception. At that time the modern plan of drafting vessels was practically unknown, and the solid model of to-day was not dreamed of. The way they built vessels then was simply to lay a keel, set up a stem and sternpost, and fill in between with frames, shaping the hull by the eye as the work progressed. Of course the two sides of the vessel were seldom of exactly the same shape, so that a vessel would often sail faster on one tack than she would on the other. But it was years before the shipbuilders adopted a more exact plan. However, the builders of the Dash meant to have a vessel that could show the highest rate of speed. They knew that a vessel that was to run the gantlet of English war ships must be a "flier," and they went to work to build one. They began with a model, the first ship's model that Maine ever knew. It was not like the solid models by which ships are built nowadays. It was the skeleton of half a vessel, made by nailing upon a backboard pieces of wood cut to represent halves of frames, and tacking rib-bands of wood upon them. These they trimmed and cut until the lines of the hull were perfected and what seemed to be the required shape for speed had been secured, and then they laid the keel.  Only a few rotten piles now remain of the wharf where the Dash was launched; the yard where so many fine vessels were built has long since been overrun by grass; but this rough model of the Dash has been carefully preserved as an heirloom, and is now in the possession of the namesake of one of these builders. This model, which was in the Maine exhibit at the World's Fair, shows that the sharp floor lines of the modern yacht are not of recent origin. This vessel, built in 1812, might easily be mistaken for one of the Burgess class, but for its almost perpendicular sternpost. The bow is sharp and thin, the run begins amidships, and all the floor timbers are at an angle much sharper than those of any merchant craft of to-day. The Dash was not originally designed for a privateer. But for years both English and French vessels had troubled the Americans, and when the embargo was ordered no ordinary craft could venture to sea. Ships lay dismantled at the wharfs, and the merchant marine of the United States was literally paralyzed. West India products naturally sold at exorbitant prices, and immense profits were to be made out of risky voyages. So, when war was declared, the Porters built the Dash, to operate much like the blockade runners of our Civil War. The United States was then practically without a navy, but five craft that could be properly classed as fighting ships being then in existence; while England had more than eighty vessels regularly cruising in these waters, and sometimes showed more than a hundred sail in the North Atlantic. The superiority of American ships and the skill of the American sailor had already been proved, and Yankee confidence felt equal to the emergency. The Dash was rigged as a topsail schooner, a style never seen in these days. She slipped down to Santo Domingo unobserved, disposed of a cargo at good prices, loaded with coffee, and was well on her way home when she was sighted by a British man-of-war, which sent her a cannon-ball invitation to come about and await the pleasure of his Majesty's representative. The captain simply piled on canvas, threw overboard enough of the cargo to let his little schooner take her racing form, and took not French, but Yankee leave of the Englishman. The strain to the Dash nearly took out her foremast. Her master had discovered that a little alteration would improve her sailing qualities, so a heavier spar was put in the place of the injured foremast, and square sails were added, making the Dash a hermaphrodite brig. A tremendous spread of light sails was given her, and then she was ready to get away from anything that John Mil was likely to send across the sea. The Dash had no sheathing; copper was too costly; but to prevent the bottom from becoming foul, she was given a coating of tallow and soap just before she sailed,—which was good while it lasted. She was chased by war vessels on her second voyage, one of them a seventy-four-gun ship, but sailed away from them; although once, at a pinch, she was forced to sacrifice her two bow guns and part of her deck load. So far the Dash's duty had been only to get away from her enemies, but now the fighting fever was upon the American sailors. It had been decided that it was better fun to take cargoes out of the enemy's ships than to run away from them, and cheaper than to purchase cargoes in ports. And so the little Dash was fitted out as a privateer. Two eighteen-pounders took the place of her small broadside guns; the "long torn," which was mounted amidships, was retained. With a larger crew she started out, determined to capture any British merchantman that was sighted. But the first vessel she met was a man-of-war, and she was obliged to resort to her old trick of running. The next was a cruiser of about her 'own, size, which she vanquished, carrying a fine cargo to port. Then she encountered the armed British ship Lacedæmonian and captured her, together with the American sloop which she was carrying off in triumph. A little later, being chased by a frigate and a schooner, she out-sailed the frigate and whipped the schooner. Her captain at that time was William Cammett, a man whose merits President Lincoln long afterwards recognized by making him inspector of customs at Portland. The Dash went on taking cargoes and prizes, until she was the pride of Portland and the detestation of the British men-of-war, who could no more catch her than they could catch a will-o'-the-wisp. She was placed under the command of Captain John Porter, a young brother of the owners, who was only twenty-four years old, but had already made a record on the quarter-deck. Within a week from the time he left port he had recovered the American privateer Armistice, which had just been taken by the English frigate Pactolus, and in another week had added two brigs and a sloop to his list of prizes. In the space of three months he sent home six prizes. Under Captain Porter's command the Dash reached the height of her fame. She had never known a defeat, had never even been injured by an enemy's shot, and it was claimed that she had not her equal in speed. It was esteemed a high honor to belong to her crew, and there was great competition for the privilege. In the middle of January, 1815, the Dash set out upon her last cruise. The crew were unaware that a treaty of peace had been signed between Great Britain and the United States, and were eager for more glory and more prize money. The light canvas was crowded upon the tall, tapering masts, and the rakish craft was Dashing up and down the harbor, but had to wait for the coming of the captain, who was taking leave of his young wife. A signal gun had summoned him, but he waited for a second, as if with a presentiment of the long parting. What little more is known of the Dash is told by the crew of the Champlain, a new privateer which had waited in the harbor to try her speed against that of the Portland champion on an outward cruise. Leaving the harbor together, the two ships took a southerly course. Gradually the Dash drew away to the front, and at the close of the next day was far ahead. A gale came on, and the last seen of the Dash she was shooting away into driving clouds of snow, which soon hid her from sight. The master of the Champlain altered his course, through fear of the Georges Shoals, and rode the gale safely; but the Dash was never heard from again. It is probable that Captain Porter failed to estimate his speed correctly and was upon the shoals before he suspected danger. For months and even years those whose loved ones had gone out in the Dash refused to believe them lost. But never a piece of wreckage reached the shore, no floating spar or splintered boat ever appeared to offer its mute testimony. The vessel had as completely disappeared as if she had been one of her own cannon balls dropped into the sea, and only time-stained records of her successful voyages remain, with the ancient model, as mementos of the famous Yankee privateer. Any one who wishes to see the Dash's record can find the ancient papers at the Portland customhouse; and the record is indeed a proud one. The largest and most powerful ocean towboats ever built were made by the Morse Towage Company, at Bath. It was proved that these boats were stanch enough for any service, and of a remarkable speed for their build, when the R. M. Morse, the first one built, pursued the Leary raft in a northeasterly gale that drove almost everything else to shelter. Another large vessel built at Bath was the barge Independent, carrying a cargo of five thousand tons, the largest of its kind ever constructed. The fishing vessels built in Maine have often proved, at the dangerous Banks, their superiority to all others. The Ocean Chief, built at Thomaston by C. C. Morton & Co., was a half-clipper intended to prove that a vessel may have cargo capacity and fleetness too, and she was a great success. The Governor Robie, built at Bath by William Rogers, not many years ago, was of the best oak, and her experience has been regarded as a proof of the superiority of wooden vessels over iron ones. She weathered a three days' storm on the rocks off Cape Elizabeth, where an iron ship would inevitably have gone to pieces. The Gold Hunter, built at Brewer, was the stanch ship that was first to "round the Horn" carrying miners bound for the California gold fields. She had been built for other things, but just before the day set for her launching the news of the great gold discoveries on the Pacific coast reached Bangor. Immediately the ship carpenters were set to work to divide off little staterooms between her decks, and soon she was ready to take as passengers a hundred and thirty-two men, the first of the famous forty-niners. Maine's ancient glory as a builder of ships may never return to her, although, while her great river leads from almost unlimited tracts of primeval forest straight to the sea, "the road of the bold," we need not despair of it. Even her cotton and iron manufactures may fail, but while she has her rocks and her cold—the best climate possible for the formation of ice of commercial value—we may hope that she will yet call home her enterprising sons who have strayed away from her, and take her place in the foremost rank of wealth-producing states, as she now ranks among the first in the production of many things that are better than wealth. |