| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

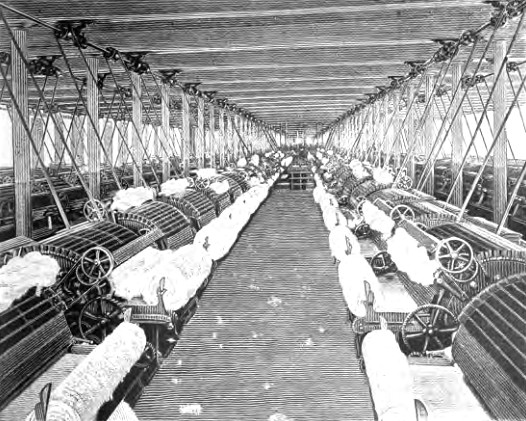

XXII. SOME OF MAINE'S RESOURCES.

FOR a hundred and thirty years Maine was a sort of adopted daughter of Massachusetts, and, devastated as she was by the long and bloody French and Indian wars, she doubtless stood in need of such protection as Massachusetts could and did bestow upon her. But there were, nevertheless, great disadvantages in this dependence. Massachusetts, although in general kind and considerate, was sometimes more domineering and more selfish than anybody but a bad stepmother can be. The independence which she grudgingly granted might have been attained much earlier but for Maine's inward dissensions. The question of separation had become a party issue, the Republicans contending for independence, the Federalists adhering to Massachusetts. The changes of political nomenclature are confusing, and unusually so in this case, where one of the parties adopted the name of its original opponents. It was in reality the nationalists who came to be called Federalists. They held to the unity of the nation, as opposed to a confederacy. The old federals, supporters of the idea of the confederation, were afterwards, with Jefferson for leader, known as Republicans, later as Jeffersonian Democrats, finally simply as Democrats. In 1820 the point was carried and the separation made. The connection had been carried on, through all the years of pioneer struggle, with more or less of good will and family affection, and it was severed in mutual friendship and respect. The new state of Maine had a population of nearly three hundred thousand, and both wealth and population immediately increased. She has not steadily increased in population. Lumber and shipping, her great sources of income in the past, have declined, and yet her increase in wealth has gone steadily on. The place of the lumbering interest was taken by the comparatively new industry of cotton manufacture. Iron-working, boot-and shoemaking, flouring mills, woolen factories, and leather-making came instead of the building of ships. And more recently than these there has come, especially in the Aroostook highlands, a skilled husbandry, which has sometimes been thought Maine's great and fatal lack.  It was not nature's churlishness, not even the restless spirit of youth and the unaccountable human instinct that makes the West draw like a magnet, that left her such a painful legacy of untamed woodland and abandoned farms; it was not a lack of energy—the people of Maine have never been accused of being lazy; but, rather, the failure to apply to agriculture the skill and enterprise, the fertility of resource, necessary to success in any other calling. More than fifty years ago the "hermit of the Aroostook" saw the resources of that fertile and beautiful region and prophesied of its future. The "American Whig Review" of September, 1847, tells of a traveler on his way down the St. John to New Brunswick, who stops for a night, having heard that the Aroostook is "famous for salmon and scenery." He accepts the hospitality of a hermit who has lived alone, for years, near a beautiful waterfall on the river. "The valley is. one of the most beautiful and luxuriant in the world," says the hermit, who has once been a traveler and lived among men; "the only thing against it is that nearly five miles of its outlet belongs to the English government. The Aroostook River is one of the most important branches of the St. John. Its general course is easterly, but it is exceedingly serpentine, and, according to some of your best surveyors, drains upward of a million acres of the best soil in Maine. Above my place there is scarcely a spot that might not be navigated by a small steamboat, and I believe the time is not far distant when your enterprising Yankees will have a score of boats here, carrying their grain to market. Before that time you must build a canal or a railroad around my beautiful waterfall.  "An extensive lumbering business is now carried on in the valley, but its future prosperity must depend upon its agriculture. Already are the river banks dotted with well-cultivated farms, and every year is adding to their number. The soil is rich and alluvial; the staple crop is wheat. Grasses flourish here, and the Aroostook farmer will yet send to market immense quantities of cattle. The climate here is not so severe as has been supposed. The heavy snowfall prevents the ground from freezing to a great depth." This was written ten years after the famous Aroostook War, and five years after the settlement of the boundary question by the Ashburton treaty. The English had previously claimed much more than the five miles of the river's outlet which disturbed the hermit's mind. |