| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

IX. AGAMENTICUS AND PASSACONAWAY.

GORGEANA, the first city of Maine, was planted in the wilderness. The ambition of its founder, Sir Ferdinando Gorges, to establish a colony in Maine had, as we have seen in connection with the Plymouth Company, been thwarted and disappointed at every point. When he secured a private grant of twenty-four thousand acres on each side of York River, he determined to plant a small colony there at his own expense. He called his colony Agamenticus at first, from the name of the mountain, famous in the aboriginal legends, which looked down upon it. "Agamenticus" signifies, in the Indian tongue, "the other side of the river." The name is applied to a beautiful elevation, or rather three elevations joined together, well wooded, and rising by gentle slopes, not rocky or steep like the Mount Desert mountains, but with a large crowning rock upon its summit. This mountain is a famous landmark for mariners, and is thought to have been the first land of the New World that revealed itself to Gosnold, in 1603. He is supposed to have landed at York Nubble and to have named it Savage Rock. The mountain is five or six miles from the shore, while Boon Island, the first land to be approached in that neighborhood, is seven miles farther. It was to Agamenticus that Wonolancet, the peace-loving son of the great Passaconaway, is thought to have retired when he refused to take part in the long and bloody King Philip's War.. St. Aspinquid, of Indian tradition, who died on the mountain, and whose gravestone is still to be seen there, is said to have been Passaconaway himself. St. Aspinquid died May 1, 1682, and is said to have been born in 1588, being therefore about ninety-four when he died. He was over forty when he was converted to Christianity, and from that time devoted himself to preaching the gospel to the Indians. His funeral obsequies were attended by many sachems of various tribes, and celebrated by a grand hunt of the warriors, at which were slain ninety-nine bears, thirty-six moose, eighty-two wild cats, and thirty-eight porcupines. That Passaconaway was living at as late a date as 1660 is shown by an anecdote of that year told of him in an ancient Indian biography. Manataqua, sachem of Saugus, had made known to Passaconaway that he wished to marry his daughter. This being agreeable to all parties, the wedding soon took place, at the residence of Passaconaway, and the hilarity wound up with a great feast. According to Indian customs when the contracting parties are of high station, Passaconaway ordered a select number of his men to accompany the newly married pair to the husband's home. When they had arrived there, several days of feasting followed, for the entertainment of such of the husband's friends as were unable to be present at the ceremony, as well as for the escort, who, when the rejoicings were over, returned to Penacook. Some time after, the wife of Manataqua expressed a desire to visit her father's house. She was permitted to go, and a select company was chosen by her husband to conduct her safely through the forest. When she wished to return to her husband, her father instead of conveying her, as before, sent to the young sachem to come and take her away.  Manataqua was highly indignant at this message, and sent his father-in-law this answer: "When she departed from me, I caused my men to escort her to your dwelling, as became a chief. She now having an intention to return to me, I did expect the same." The elder sachem was angry in his turn, and sent back an answer which only increased the difficulty, and it is supposed that the connection between the new husband and wife was terminated by this disregard of ceremony on the part of her father. Passaconaway's character was certainly like that ascribed to St. Aspinquid. In his youth he was supposed to have magic powers, and his people believed that he could burn a leaf to ashes and then restore to it nature's vivid greenness. They never doubted that he could raise a living serpent from the skin of a dead one, and many warriors testified that they had seen him turn himself into a flame to burn up his enemies. As for St. Aspinquid, we may well believe that his assumption of magic powers was not wholly abandoned after he embraced Christianity, for most of the praying Indians clung to some of their savage superstitions, and sometimes would divest themselves of their new religion as suddenly as if it were a blanket, and rush frantically into a powwow or a war dance, or even a frenzy of slaughter. But St. Aspinquid died firm in the faith delivered to him by the devoted Jesuit missionaries, and in his last days he endeavored to promote peace and good will between his people and the whites. In 1660, when he felt his end to be drawing near, he made a great feast, to which he invited all his widely scattered tribes, calling them his children. "Hearken," he said, "to the last words of your father and friend: The white men are sons of the morning. The Great Spirit is their Father. His sun shines bright about them. Never make war with them. Sure as you light the fires, the breath of heaven will turn the flames upon you and destroy you. Listen to my advice. It is the last I shall be allowed to give you. Remember it, and live." A

poem on Passaconaway, written by a bard of the old days, and

extremely popular as a fireside tale, is too delightfully quaint to

be allowed to pass into oblivion: "'Tis

said that sachem once to Dover came

From Penacook, when eve was setting in; With plumes his locks were dressed, his eyes shot flame; He struck his massy club with dreadful din, That oft had made the ranks of battle thin. Around his copper neck terrific hung A tied-together bear and catamount skin; The curious fish bones o'er his bosom swung; And thrice the sachem danced, and thrice the sachem sung. "Strange man was he! 'Twas said he oft pursued The sable bear and slew him in his den, That oft he howled through many a pathless wood And many a tangled wild and poisonous fen That ne'er was trod by other mortal men. The craggy ledge for rattlesnakes he sought, And choked them one by one, and then O'ertook the tall gray moose as quick as thought, And then the mountain cat he chased, and chasing caught. "A wondrous wight! For o'er Siogee's ice With brindled wolves, all harnessed three and three, High seated on a sledge, made, in a trice, On Mount Agiocochook of hickory, He lashed and reeled and sung right jollily. And once, upon a car of flaming fire, The dreadful Indian shook with fear to see The king of Penacook, his chief, his sire, Ride flaming up toward heaven, than any mountain higher!"

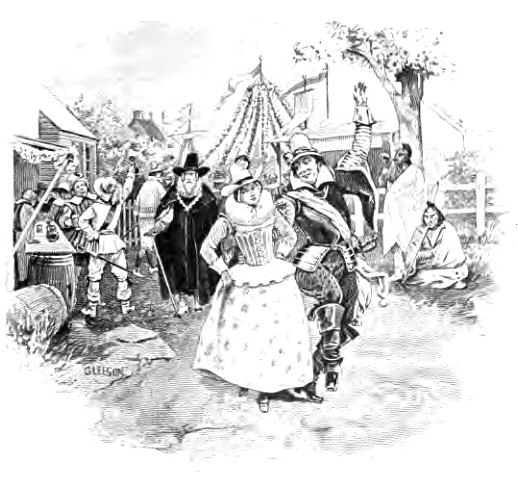

The last line suggests the curious reverence of the Indians for mountain peaks, and their dread of the evil spirit whom they supposed to inhabit them. They believed that the devout St. Aspinquid had banished it from Agamenticus, but thought it dangerous to ascend any other high mountain. The summit of Mount Katandin they thought the home of Pamola, an evil spirit very great and very strong indeed. His head and face were said to be like a man's, his body and feet like an eagle's, and he could take up a moose with one of his claws. Pamola did not like snowtime, so the tradition ran, and at the beginning of winter he rose with a great noise, and took his flight to some unknown warmer region. The story is told of seven Indians who, a great many moons ago, too boldly went up the mountain, and were certainly killed by the mighty Pamola, for they were never heard of more. The tradition handed down from earliest times was that an Indian never goes up to the summit of Katandin and lives to return. Passaconaway had banished the evil spirit from Agamenticus, but the Indians themselves were soon driven away by the new settlement. Gorges's long-thwarted ambition demanded a great and striking success for his colony. He was not willing to build a little hamlet and see it gradually expand into a village and then a town, after the humble fashion that prevailed in Maine. Instead, he inaugurated a city with pomp and ceremony,—an old-world city, whose mayor and all civil officers wore gorgeous uniforms and the insignia of their rank. The mayor was called upon to hold semiannual fairs, on the feasts of St. Peter and St. James, and to make arrangements that they should be held perpetually.  It was evidently intended to form by ceremonial and festival an attractive contrast to the plainness and austerity of the Puritan settlements in other parts of Maine. The

poet of Sir Ferdinando's city has perhaps exaggerated a little. He

writes: "For

hither came a knightly train

From o'er the sea with gorgeous court; The mayors, gowned in robes of state, Held brilliant tourney on the plain, And massive ships, within the port, Discharged their load of richest freight. Then when at night, the sun gone clown Behind the western hill and tree, The bowls were filled, this toast they crown: 'Long live the city by the sea!'" But the city was not destined to live long. Massachusetts assumed control of Maine by virtue of her charter from the English king, and after some resistance the inhabitants allowed a large part of the territory to be annexed to Massachusetts. Sir Ferdinando Gorges died, and his nephew, Thomas Gorges, who had been deputy governor of the province of Maine, and was then living in state at Gorgeana, had gone on a visit to England to secure influence to settle the disturbed condition of affairs in Maine. In his absence the city was sacrificed to the ambition of the Massachusetts Bay Company. It was sold out to a company, and when Gorges returned he found even his residence despoiled, nothing remaining but an old pot, a pair of tongs, and a couple of andirons. The "civic splendor" had all departed, but it remained a town, and in 1652 it was ordered at a town meeting that "William Hilton have use of ferry for twenty-one years, to carry strangers over for twopence and for swimming over horses or other beasts, four-pence, or for one swum over by strangers therewith, he or his servants being ready to attend." The overland route from Maine to Massachusetts was close by the ocean, and the ferry in constant demand. The Indians in that region, whether through the influence of Passaconaway or through the friendliness of the settlers, seem to have been less hostile than in the adjoining towns; for, on their journeys, they frequently patronized the ferry, their way of announcing themselves as passengers being by a blood-curdling war whoop at Mr. Hilton's gate. Even in the darkness of the evening, Mrs. Hilton would answer the signal, and herself ferry the savages across. A squaw who had been indulging in fire water, one day, became enraged at Mrs. Hilton's refusal to ferry her over, and threw a knife so that it cut off the "thumb ca " of the door latch. But she returned the next day, deeply penitent, and with promises of future good behavior. The part of the territory of Maine which had been annexed to Massachusetts was called the county of Yorkshire, and Agamenticus, the late city of Gorgeana, received the name of York. But while York continued to keep peace with its neighboring Indians, the bands of savages that roamed, plundering and slaughtering, through the country often swooped down upon it; and in February, 1692, while it was still only a little village scattered along the bank of the Agamenticus River, it was entirely destroyed, except the garrison houses, by a company of nearly three hundred French and Indians, who had come through the wilderness from Canada on snowshoes. In half an hour they had killed seventy-five of the inhabitants, and taken more than a hundred prisoners. Many of the prisoners were severely wounded, and were carried away, in the bitter cold of the winter, by the ruthless savages, and very few of them ever saw home or friends again. But the little town arose from its ashes. At the close of the dreadful King William's War, which was the second Indian war and lasted ten years, while King Philip's War, bloody and devastating as it was, had lasted but three, the destitution and suffering in Maine were extreme. "No mills, no inclosures, no roads, but, on the contrary, dilapidated habitations, wide, wasted fields, and melancholy ruins." But the people of York were not wholly discouraged. Among other things, they wanted a gristmill. The united resources of the town were not sufficient to build one; so they offered to a man in Portsmouth a lot of land to build a mill upon, liberty to cut all the timber that he needed, and their pledge to carry all their corn to his mill, so long as he kept it in order. They could not live without the mill, and they suffered great suspense for a time, lest their offer should not be accepted. What had been Sir Ferdinando's proud city now depended upon a gristmill, or the hope of one, for its continued existence. The mill was built, and gradually the scattered people returned and rebuilt their little log houses. But there was no peace for the plucky pioneers. The first disturbance originated in a report that the settlers were organizing for a war of extermination upon the savages. The Indians were frightened, and began to withdraw from the settlements. Even Passaconaway's peaceful tribes took alarm, and their departure led the inhabitants to believe that they were to join a general uprising of the tribes. The militia was ordered out, and well-armed soldiers patrolled the town of York, every night, from nine until morning. The townspeople listened, doubtless with heart-sickening dread, for the war whoop that should mean more than a demand for Goodman Hilton's ferryboat. But this time the horrors of bloodshed were averted. Governor Dudley arranged a council with the sagamores of the eastern tribes at Falmouth, the 20th of June, 1703. Knowing that the Indians were greatly impressed by pomp and ceremony, the governor came to the council with an imposing retinue. But the splendor of the Indians altogether eclipsed that of their white brethren. There were eleven sagamores, and they entered Portland harbor with a fleet of sixty-five canoes, containing two hundred and fifty warriors, decorated with plumes and war paint, and wearing garments gorgeous with fringes and beaded embroidery. Governor Dudley had brought a great tent, in which were gathered his suite and all the Indian chiefs. He made a speech to the Indians, in which he declared that it was his wish to reconcile every difficulty that had arisen since the last treaty, and that he would esteem them all as brothers and friends. Simms of the Penobscots was the Indian orator of the occasion, and he bore himself with much dignity. "We thank you, good brother, for coming so far to talk with us," he said. "It is a great favor. The clouds gather and darken the sky. But we still sing with love the songs of peace. Believe my words. So far as the sun is above the earth, so far are our thoughts from war or from the least desire of a rupture between us." Peace was ratified and presents exchanged, after the Indian fashion. There were professions of strong friendship on either side, and the hearts of the people rejoiced. Those who had been ready to depart to safer regions remained, and there was even a little emigration to the Maine shores, where land was cheap, valuable timber abundant, the soil rich, and the fisheries increasingly profitable. But only two months after this encouraging peace was made, a company of five hundred French and Indians swooped down upon the shore towns, Cape Porpoise, Wells, York, Saco, and Casco. Few details remain to us, but it is evident that the slaughter and destruction were terrific, and, except the garrison houses, scarcely a building remained in those towns. In 1707, the six English settlements which were all that survived in Maine were those of Wells, Berwick, Kittery, Casco, Winter Harbor, and York. The settlers continued to suffer constantly from the prowling savages. In the summer of 1712 twenty-six of the English were killed or carried into captivity in the neighborhood of York, Kittery, and Wells. They could not venture into the fields without danger of being murdered. Children playing upon the doorsteps would be dragged off by the savages before their mothers' eyes. One of the scouting parties which were continually on the march for the defense of the settlements was surprised, between York and Cape Neddick, on the 14th of May, 1712, by a company of thirty Indians. The leader of the scouting party, Sergeant Nalton, was instantly killed, and seven others, probably wounded, were captured. The survivors fled for their lives, and succeeded in reaching the garrison. A Mr. Pickernel, hearing of the Indian assault, had left his house, with his family, to take refuge in the garrison, when an ambushed Indian shot him dead. His wife was wounded, and his little child was scalped. The child, left for dead, eventually recovered from the frightful wound,—which was very unusual for a victim of the Indians' scalping. The story of York has seemed worth the telling, not only because it was the first city of Maine, but because it was one of the towns which through all the wars bore the brunt of the Indians' fury, and its survival shows the noble courage and persistence of its settlers. Wells, the adjoining town, was another settlement upon which the Indians' vengeance was especially fierce. The story of a little captive from that town forms one of the most romantic chapters in Miss C. A. Baker's "True Stories of New England Captivities." Little Esther Wheelwright was the granddaughter of the Rev. John Wheelwright, the first minister of Wells. He was a man of high character and great spirituality, but of doctrinal peculiarities which had not found favor with his Puritan brethren in Massachusetts. So in 1643 he removed to Wells, and although he afterwards returned to England, his son, who was also John Wheelwright, remained, shared the fearful struggles with the Indians, and was known until his death as a highly respected citizen. His daughter, little Esther, was doubtless a typical Puritan girl, dutifully sharing in the household tasks of the bare and primitive living, learning her catechism, and walking to "meeting" in the blockhouse under the protection of her father's gun; and also imbibing a wholesome horror of Indians, and of the papistical French, their allies.  In the blockhouse her sister Hannah had been married, on the 16th of September, 1712, to Elisha Plaisted, a young man of Portsmouth. The Wheelwrights were one of the first families of Wells, and young Plaisted also had good social connections and an extensive acquaintance. There were guests from Portsmouth and Kittery, from York, and even from Falmouth. Some came by water, some in companies on horseback, and all were well armed. For once, privations should be forgotten, terrors thrown to the winds, and the garrison house, stained with blood and hacked by tomahawks though it might be, should be decked for a bridal. But alas! there were unexpected, unwelcome guests. The Indians had heard of the proposed festivities, had even made themselves acquainted with the ways by which the wedding guests were to come and go. The ceremony was performed, and there was frolic and feasting. It is quite likely that it lasted well into the small hours; when good times are rare, people are apt to make the most of them. The first of the guests to leave found that two of the horses were missing. Sergeant Tucker, Isaac Cole, and Joshua Downing went out in search of them. While they were, still very near the blockhouse, from behind the trees came the fierce volleys of two hundred savages ambushed in the forest. Joshua Downing and Isaac Cole fell dead, and Sergeant Tucker, seriously wounded, was taken captive. Out of the blockhouse rushed every man of the company at the sound of the guns. Many of them were military men, and accustomed to Indian warfare, but they did not realize how great was the number of their foes. They sprang upon their horses, and, in small companies, rode off, in different directions, to waylay the Indians and cut off their retreat. But on each path that they took were Indians lying in ambush. Elisha Plaisted, the bridegroom, who was very brave, led seven or eight men, and they rode directly into an ambush. With one volley the Indians killed every horse. One man was killed, and young Plaisted was captured and carried away in his wedding garments. In their anxiety to secure Plaisted the Indians allowed the others to escape. His father was a comparatively rich man, and they expected to extort from him a large ransom for his son. He was finally ransomed by the payment of £300. But when, in a fiercer raid and slaughter, little Esther Wheelwright was taken captive, the Indians disappeared with their prey into the heart of the forest, and there was no possibility of a ransom. She suffered hardship in the long journey through the winter woods to Canada, but the Indians do not seem to have treated her cruelly. We hear of her next in the Ursuline Convent at Montreal, where the sisters have speedily transformed the granddaughter of the Puritan divine into a novice with white veil and crucifix. She became a devout nun, and although she was at liberty to visit her home, she never cared to do so. She died full of years and sainthood, the mother superior of the Ursuline Convent. Little Mary Sereven, who was the daughter of a Baptist minister, was carried away by the Indians at the same time with Esther Wheelwright. She also became a member of a Roman Catholic sisterhood, but of her story little is known. In spite of the continued Indian depredations, these coast towns gradually increased and prospered. In 1725 York was, next to Falmouth, the most important town in Maine. It was of political consequence, the shire town, and its inhabitants were men whose opinions had weight in the councils of the colony. Perhaps this was, after all, better than the "civic splendor" of Sir Ferdinando's ambition. There was, indeed, before long, not a little wealth and refinement of living. The last negro slaves held in New England were owned there, and the oldest inhabitant remembers going to the funerals of two of them and seeing them buried at the feet of the master and mistress who had died before them. Now the beautiful York coast and harbor and the pretty winding river have attracted swarms of summer visitors. Hotels line the wide beaches, and sounds of revelry by night awaken even the echoes on Passaconaway's lonely mountain. No trace remains of the famous old sagamore and saint, except the grave that is to be seen on Agamenticus, and his name, bestowed upon a fine hotel. |