| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

XIII

IN THE REIGN OF THE ROYAL GOVERNORS

THE year in which Sewall

died marked the appointment of Jonathan Belcher as governor of

Massachusetts.

He was the sixth governor to be sent out by the crown and the third who

was a

native of the province. But he succeeded in his office no

better than the

gentlemen who had preceded him, the wrangling which had become

a regular

feature of legislative life here marring his administration as it had

done

those of his predecessors. Belcher was the son of a prosperous Boston

merchant

and a graduate of Harvard College. He was polished and sociable and had

had the

benefit of extensive travel. But he found himself in an impossible

situation

and the only thing for him to do was to make as few enemies as possible

and

wait for death or the king to remove him. People who for two

generations had

been practically independent were not going to take kindly to

any appointee of

a throne they were determined to find tyrannical.

Of course the opposition was

by no means unanimous. Quite a few persons there were in Boston and its

nearby

towns to whom the old regime, with its subserviency to men like the

Mathers,

had been noxious in the extreme, and they naturally welcomed the

change. But to

most of those who in lineage, sentiment, and habit, represented the

first

planters the foisting upon New England of a royal governor,

bound in loyalty

to a far-off king, was an affront to be neither forgiven nor

condoned. Though

the holder of this office had been a man of superhuman breadth and of

extraordinary generosity he would not have been acceptable to this

portion of

the inhabitants. William Phips had been indigenous to a degree found in

no man

elected by the people. But he suited neither the Mathers, who nominated

him,

nor the common people who hated the Mathers. Even the Earl of

Bellomont, the

"real lord" who succeeded Phips, got on better with the captious

people who moulded public opinion in Boston than did this Maine

carpenter.

For a time, indeed, it

looked as if Bellomont were going to get on very well indeed. A

vigorous man

of sixty-three, fine looking, with elegant manners and courtly ways, he

had

little difficulty, at first, in making friends with even the least

friendly of

the Bostonians. Churchman though he was, he was not averse to

attendance at the

Thursday lecture and this, of course, made upon the stiff-necked

Puritans just

the impression he had calculated that it would.

The Assembly hired of Peter

Sergeant for him the Province House afterwards renowned as the official

home of

the governors, and here he entertained handsomely. By a curious

coincidence his

lady thus succeeded as mistress of the handsome mansion Lady Phips,

whom Peter

Sergeant had married for his third wife. The builder, owner and first

occupant

of what is perhaps the most interesting house in colonial

history was a rich

London merchant who carne to reside here in 1667 and died here

February 8,

1714. Sergeant had held many offices under the old charter government,

was one

of the witchcraft judges and, when Andros had been deposed, played an

important

part in that proceeding. That he was a very rich man one must conclude

from the

extreme elegance of the homestead which he erected, nearly

opposite the Old

South Church, on a lot three hundred feet deep with a frontage of

nearly a

hundred feet on what was then called High street but which we now know

as

Washington street.

The house was square and of

brick. It had three stories, — with a gambrel roof and lofty

cupola, the

last-named adornment surmounted with the gilt-bronzed figure of an

Indian with

a drawn bow and arrow. Over the portico of the main entrance was an

elaborate

iron balustrade bearing the initials of the owner and the date

"16 P. S.

79." Large trees graced the court-yard, which was surrounded by an

elegant

fence set off by ornamented posts. A paved driveway led up to the

massive steps

of the palatial doorway. Two small out-buildings, which, in

the official days

served as porters' lodges, signified to passers-by that this

house was indeed

the dwelling-place of one who represented the majesty of England.

The Province House

Hawthorne in his

"Legends of the Province House" has repeopled for us this impressive

old mansion and, at the risk of anticipating somewhat the arrival of

governors

not yet on the scene, I shall quote his description while suppressing,

as far

as possible, his allusions to the deplorable condition of the house at

the time

he himself visited it: " A wide door with double leaves led into the

hall

or entry on the right of which was a spacious room, the

apartment, I presume,

in which the ancient governors held their levees with

vice-regal pomp,

surrounded by the military men, the Counsellors, the judges,

and other

officers of the Crown, while all the loyalty of the Province thronged

to do

them honour.... The most venerable ornamental object is a

chimneypiece, set

round with Dutch tiles of blue-figured china, representing scenes from

Scripture; and, for aught I know, the lady of Pownall or Bernard may

have sat

beside this fireplace and told her children the story of each blue

tile. . .

"The great staircase,

however, may be termed without much hyperbole, a feature of grandeur

and

magnificence. It winds through the midst of the house by flights of

broad

steps, each flight terminating in a square landing-place,

whence the ascent is

continued towards the cupola. A carved balustrade... borders the

staircase with

its quaintly twisting and intertwining pillars, from top to bottom. Up

these

stairs the military boots, or perchance the gouty shoes of many a

Governor have

trodden, as the wearers mounted to the cupola, which afforded them so

vide a

view over the metropolis and the surrounding country. The cupola is an

octagon

with several windows, and a door opening upon the roof....

Descending... I

paused in the garret to observe the ponderous white oak

framework, so much

more massive than the frames of modern houses, and thereby resembling

an

antique skeleton."

The cheerful task of

recalling the courtly functions of the Province House in its bright

days has

been ably discharged by Edwin L. Bynner — who, writing in the

Memorial History

of Boston on the "Topography of the Provincial Period" invokes

"this old-time scene of stately ceremonial, official pomp or social

gayety,

of many a dinner rout or ball. Here dames magnificent in damask or

brocade,

towering head-dress and hoop petticoat — here cavaliers in

rival finery of velvet

or satin, with gorgeous waistcoats of solid gold brocade, with wigs of

every

shape, — the tie, the full-bottomed, the ramillies, the

albermarle, — with

glittering

swords dangling about their

silken hose — where, in fine, the wise, the —

witty, gay and learned, the

leaders in authority, in thought and in fashion, the flower of old

Provincial

life, trooped in full tide through the wainscoted and tapestried rooms,

and up

the grand old winding staircase with its carved balustrade and its

square

landing-places, to do honour to the hospitality of the martial Shute,

the

courtly

Burnet, the gallant Pownall,

or

the haughty Bernard."

At the time of Bellomont's

administration, however, the house had not Yet become

identified with any

great amount of official grandeur. The Boston of that year (1619)

impressed one

traveller, indeed, as a very poor sort of place. This traveller's name

was

Edward Ward and he is worth some attention as a wit, even though we may

need to

discount a good deal of what he wrote about the chief town of New

England:

"The Houses in some parts Joyn as in London," he says, "the

Buildings, like their women, being neat and handsome; their Streets,

like the

Hearts of the Male Inhabitants are paved with Pebble. In the

Chief or High

street there are stately Edifices, some of which have cost the owners

two or

three thousand pounds the raising; which, I think, plainly

proves two old

adages true, — viz that a Fool and his Money is soon parted,

and Set a Beggar

on Horseback he'll Ride to the Devil, — for the Fathers of

these men were

Tinkers and Peddlers. To the Glory of Religion and the Credit of the

Town there

are four Churches.... Every Stranger is invariably forc'd to take this

Notice.

Wit in Boston there are more religious zealouts than honest men.... The

inhabitants seem very religious showing many outward and visible signs

of an

inward and Spiritual Grace but though they wear in their Faces the

Innocence of

Doves, you will find them in their Dealings as subtile as Serpents.

Interest is

Faith, Money their God, and Large Possessions the only Heaven they

covet. Election,

Commencement and Training days are their only Holy-Days. They keep no

saints'

days nor will they allow the Apostles to be saints; yet they assume

that sacred

dignity to themselves, and say, in the title-page of their Psalm-book,

'Printed

for the edification of the Saints in Old and New England.' "

A witty fellow certainly,

this taverner and poet whom Pope honoured with a low seat in the

Dunciad and

who so cleverly hit off the peculiarities of our Puritan forbears that

we have

to quote him whether we will or no. In connection with the law against

kissing

in public he tells a story — which has since become

classic of a ship captain

who, returning from a long voyage, happened to meet his wife in the

street and,

of course, kissed her. For this he was fined ten shillings. "What a

happiness,"

comments Ward, "do we enjoy in old England, that can not only kiss our

own

wives but other men's too without the danger of such a penalty." Ward

regarded our women as highly kissable, observing that they had better

complexions than the ladies of London. "But the men,

— they are generally

meagre and have got the hypocritical knack, like our English Jews, of

screwing

their faces into such puritanical postures that you would think they

were

always praying to themselves, or running melancholy mad about some

mystery in

the Revelations."

One of the chief objects

that the king had in mind in appointing Lord Bellomont

governor was the

suppression of piracy, which had long been an appalling scourge on the

whole

American coast. The new incumbent did not disappoint his royal master,

for he

promptly arrested and caused to be sent to England for subsequent

hanging the

notorious Captain Kidd, who, from pirate hunting with Bellomont as

silent

partner, himself turned pirate and had to be given short shrift. While

Kidd was

in jail he proposed to Bellomont that he should be taken as a prisoner

to

Hispaniola in order that he might bring back to Massachusetts the ship

of the

Great Mogul, which he had unlawfully captured, and in the huge

treasure of

which Bellomont and his companions would own four-fifths if the prize

were

adjudged a lawful one. Bellomont refused this offer, for he well knew

that the

Great Mogul Is ship ought not to have been attacked inasmuch as that

personage

was on friendly terms with England. It is to this "great refusal" of

Bellomont that we owe the mystery that to this day enshrouds

the whereabouts

of Captain Kidd's treasure.

Bellomont died in New

York-whither

he had gone for a short visit — March 5, 1701, after a

sojourn in Boston of a

little over a year. The stern-faced Stoughton again filled the gap as

the head

of the government. And then, on July 11, 1702, there arrived in Boston

harbour

as governor that Joseph Dudley who, eleven years before, had been sent

out of

the country a prisoner in the "crew" of the hated Andros. Dudley has

been more abused than any of the royal governors. Most historians speak

of him

as "the degenerate son of his father" but, as far as I can see, they

mean by this only that he honoured the king instead of the theocracy

and

attended King's Chapel instead of the Old South Church. He had been

born in

Roxbury July 23, 1647, after his father had attained the age of

seventy, and was

duly educated for the ministry. But, preferring civil affairs to the

church, he

held various offices and was sent to England in 1682, one of

those charged

with the task of saving the old charter. He soon saw that this could

not be

done and so advised the surrender of that document,

— counsel which, of

course, caused him to be called a traitor to his trust. But it served

to

recommend him to the royal eye and brought him the appointment of

President of

New England. How he was imprisoned, how he attempted

escape and how he was

finally punished (?) in England we have already seen. Dudley

was in truth much

too able a man to be ignored. During the almost ten years of his exile

from

America, he not only served as deputy governor of the Isle of Wight but

he was

also a member of Parliament. Most interesting of all he

enjoyed the close

friendship of Sir Richard Steele, who acknowledged that he "owed many

fine

thoughts and the manner of expressing them to his happy acquaintance

with

Colonel Dudley; and that he had one quality which he never knew any man

possessed

of but him, which was that he could talk him down into tears when he

had a mind

to it, by the command he had of fine thoughts and words adapted to move

the

affections." Even those who admired Dudley did — not

invariably trust him,

however. Sewall, whose son had married the governor's daughter, records

that

"the Governor often says that if anybody would deal plainly with him he

would hiss them. But I (who did so) received many a bite and many a

hard word from

him." Dudley, first among the royal governors, began that

fight for a

regular salary which lasted almost as long as did the office. For some

time he

refused the money grants which were voted to him but, when he found

that he

would get nothing else, he at last gave way. Yet he was so unpopular

that there

was hardly any year when he received more than six hundred pounds. When

Queen

Anne died he knew that his power must come to an end. So he retired

from public

office to his estate at West Roxbury, where he died in 1720,

having bequeathed

fifty pounds to the Roxbury Free school for the support of a Latin

master. All

his life he had been a conspicuous friend of letters and, in

distributing

commissions, he uniformly gave the preference to graduates of the

college for

which he had clone so much.

To the year of Dudley's

death belongs the institution of what is perhaps Boston's most unique

educational enterprise, — "a Spinning School for the

instructions of the

children of this Town." There had arrived in Boston, shortly before

this,

quite a number of Scotch-Irish persons from in and about

Londonderry, bringing

with them skill in spinning and a habit of consuming the

then-little-known

potato. The introduction of the potato had no immediate social effect

but the

coming of the linen wheel, a domestic implement which might be

manipulated by a

movement of the foot, was looked upon as a matter of great importance.

Accordingly, a large building was erected on Long-Acre street (that

part of

Tremont street between Winter and School) for the express purpose of

encouraging apprentices to the manufacture of linen. Spinning-wheels

soon

became the fad of the day and, at the commencement of the

school "females

of the town, rich and poor appeared on the Common with their wheels and

vied

with each other in flue dexterity of using them. A larger concourse of

people

was perhaps never drawn together on any occasion before." By a curious

kind of irony the General Court appropriated to the use of this

spinning school

the. tax on carriages and other articles of luxury.

The Common, by the bye, had

now come to be the cherished possession which Bostonians of to-day

still esteem

it. Purchased by Gov. Winthrop and others of William Blackstone in 1634

for

thirty pounds, a law was enacted as early as 1640 for its protection

and

preservation. Originally it extended as far as the

present Tremont Building,

and an alms-house and the Granary as well as the Granary Burying Ground

(established in 1660) were within its confines. It is certainly greatly

to be

regretted that the famous Paddock Elms, set out on the Common's edge in

1762 by

Major Adino Paddock, the first coach maker of the town, whose

home was

opposite the Burying-Ground, had to be removed in 1873, in order to

make way

for traction improvements!

The next governor after

Dudley was Colonel Samuel Shute, in whose behalf friends of the

Province, then

in London, purchased the office from the king's appointee for one

thousand

pounds. Shute was a brother of the afterwards Lord Barrington

and belonged to

a dissenting family. It was, of course, expected by Ashhurst,

Belcher and

Dummer — when they obtained from Colonel Elisha Burgess the

right to the

governorship — that Shute would give them their money's worth

and help them to

down the rising Episcopal party in Boston. But their incumbent promptly

showed

that he was a king's man by voting an adjournment of the court over

December

25, 1722. "The Governor mentioned how ill it would appear to have votes

passed on that day," records Sewall; and on further argument Colonel

Shute

"said he was of the Church of England."

This must have been a bitter

fact for our old friend, the justice, to write down in his Diary, for

none had

struggled harder than he against the inevitable advance of Episcopacy.

Of course

the religion of England must surely, if slowly, make its way forward in

an

English province. governed by officials sent out from England. Sewall

was too

sensible a man not to know this. But he would not raise his left little

finger

to help the matter on. His Diary abounds, as we have already seen, in

references to the difficulties encountered by those who were trying to

introduce into Boston the ways and the worship of the old country. When

Lady

Andros died he had none of his usual exclamations of pity for

the sorrow of

the bereaved husband, and when Andros tried to buy land for a

church-home

Sewall refused to sell him any.

But the governor got land

just the same, for he appropriated a corner of the burial ground for

his

church. The Reverend Increase Mather, speaking of the matter in 1688

said:

"Thus they built an house at their own charge; but can the Townsmen of

Boston tell at whose charge the land was purchased?" This refers,

however,

only to the land occupied by the original church. The

selectmen of Boston

docilely granted, in 1747, the additional parcels needed for the

enlargement of

the building then on the spot.

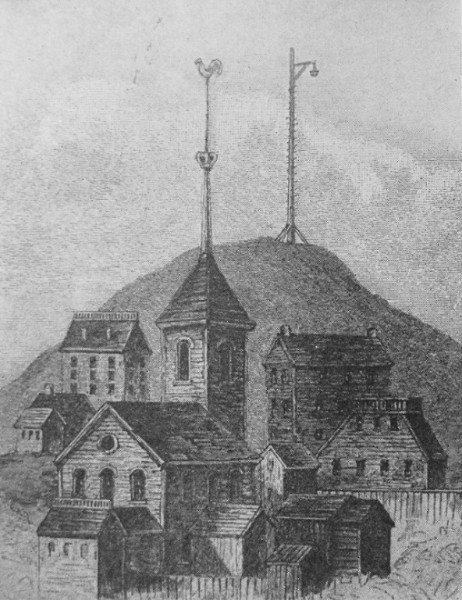

Sufficiently

unpretentious, certainly, was the

exterior of the early home of prayer-book service in Boston.

It was of wood

crowned by a steeple, at the top of which soared a huge "cockerel."

In the one cut which has come down to us of the building, the height of

this

scriptural bird rivals that of the nearby Beacon. This,

however, is very

likely attributable to an error in perspective on the part of the

"artist." Greenwood tells us that "a large and quite observable

crown" might be discerned just under this ambitious bird. The interior

of

the church was much more attractive to the eye than was the

case in the other

Boston meeting-houses. Though there were no pews for several years,

this defect

had been remedied, by 1694, as the result of a purse of fifty-six

pounds

collected from the officers of Sir Francis Wheeler's fleet, which had

been in

the harbour shortly before. Further to offset its humble exterior the

chapel

had a "cushion and Cloth for the Pulpit, two Cushions for the Reading

Desks, a carpet for the Allter all of Crimson Damask, with silk fringe,

one

Large Bible, two Large Common Prayer Books, twelve Lesser Common Prayer

Books,

Linnin for the Allter. Also two surplises." All these were the gift of

Queen Mary. There was besides a costly Communion service

presented by king and

queen. Against the walls were "the Decalougue viz., the ten

Commandments,

the Lord's Prayer and the Creed drawne in England."

The original King's Chapel and the King's Chapel of To-day.

G. Dyer, the early warden of

the chapel gave also according to his means and wrote down for

posterity the

manner of his generosity: "To my labour for making the Wather cock and

Spindel, to Duing the Commandements and allter rome and the Pulpet, to

Duing

the Church and Winders, mor to Duing the Gallary and the

King's Armes, fortey

pounds, which I freely give." In 1710 the chapel was rebuilt to twice

its

original size, to accommodate the rapidly growing

congregation. As now

arranged the pulpit was on the north side, directly opposite a pew

occupied by

the royal governors and another given over to officers of the British

army and

navy. In the western gallery was the first organ ever used in America.

The

fashion in which the chapel acquired this "instrument" (now in the

possession of St. John's parish, Portsmouth, New Hampshire) is most

interesting. It was originally the property of Mr. Thomas

Brattle, one of the

founders of the old Brattle street church and a most

enthusiastic musician. He

imported the organ from London in 1713 and, at his death, left it by

will to

the church with which his name is associated, "if they shall accept

thereof and within a year after my disease procure a sober person that

can play

skillfully thereon with a loud noise." In the event of these conditions

not being complied with it was provided that the organ should go to

King's

Chapel. The Brattle street people failed to qualify and the

Episcopalians got

the organ. It was used in Boston until 1756 and then sold to St. Paul's

church

in Newburyport, where it was in constant use for eighty years,

after which it

was acquired for the State street Chapel of the Portsmouth church,

where it

still gives forth sweet sounds every Lord's day.

High up on the pulpit of

King's Chapel stood a quaint hour-glass richly mounted in brass and

suspended

from the pillars, then as now, were the escutcheons of Sir Edmund

Andros,

Francis Nicholson, Captain Hamilton, and the governors Dudley, Shute,

Burnet,

Belcher and Shirley. It was arranged that the royal governor

and his deputy

were always to be of the vestry. Joseph Dudley accordingly hung up his

armorial

bearings and took his place under the canopy and drapery of the state

pew as

soon as ever he came back to the land in which his father had been a

distinguished Puritan. There is nothing to show that. he did not do

this

conscientiously, however. Certainly it must have been much pleasanter

here for

a governor than in the bare meeting-houses where everything he might or

might

not do would be counted to his discredit.

During Colonel Shute's term

of office the smallpox, which Boston had escaped for nearly twenty

years, again

visited the town (1721). Nearly six thousand people contracted the

disease, of

whom almost one thousand died. Inoculation was urged and

Cotton Mather did

really noble service in pushing its propaganda, soon converting to his

belief

in the efficacy of the practice Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, an eminent

physician, and

Benjamin Colman, first minister of the Brattle street Church

and for nearly

half a century (1701-1747) one of the famous preachers of the Province.

Dr.

William Douglas was the chief opponent of the new theory and he printed

in the

paper of the Franklins, his attacks upon those who urged it. Two years

after

the scourge Shute went to England on a visit from which he never

returned, and

Lieutenant Governor William Dummer took the chair, which, as the event

proved,

he was to occupy for nearly six years.

During this interim both

Increase and Cotton Mather died, the one in 1723, the other five years

later.

The father had preached sixty-six years and had presided over

Harvard College

for twenty; the son was in the pulpit forty-seven years and was one of

the overseers

of the college. To bear him to his burying-place on Copp's Hill six of

the

first ministers of Boston gave their services, and the body

was followed by

all the principal officials, ministers, scholars and men of affairs,

while the

streets were thronged and the windows were filled "with sorrowful

spectators." How expensive this funeral was I do not know, but

when

Thomas Salter died (in 1714) the bill was as follows:

|

£ s. d. 50 yds of Plush.…..................................10 8 4 24 yds. silk crepe..................................... 2 16 0 9 3-8 black cloth..................................... 11 5 0 10 yards fustian........................................ 1 6 8 Wadding.................................................. 0 6 9 Stay tape and buckram .............................7 7 6 13 yds. shalloon....................................... 2 12 0 To making ye cloths................................. 4 17 0 Fans and girdles....................................... 0 10 0 Gloves................................................... 10 9 6 Hatte, shoes, stockings............................. 3 15 0 50 1.2 yds. lutestring .............................. 25 5 0 Several rings.…........................................ 3 10 0 Also buttons, silk, cloggs... 2 yards of cypress.…............................... 3 10 0 To 33 gallons of wine @ 4s. 6d ............... 7 8 6 To 12 ozs. spice @ 18d.…...................... 0 18 0 To 1-4 cwt. sugar @ 7s.…....................... 0 18 0 To opening ye Tomb ….. To ringing ye Bells................................... 3 10 0 To ye Pauls..... Doctor's and nurse's bills......................... 10 0 0 — the whole amounting to over £100. |

Governor William Burnet

Enter now as governor

William Burnet, son of the historian bishop. He arrived in Boston July

13,

1728, and was escorted from the Neck to the Bunch of Grapes Tavern by a

large

body of enthusiastic citizens, among them the famous Mather

Byles, who dropped

into poetry on this as on many a later occasion of state. Burnet had in

his

train a tutor, a black laundress, a steward and a French cook.

Upon the

latter, as will be easily understood, the Bostonians gazed

with particular

awe. But Burnet was merely preparing to live here as he had lived in

England

and, later, in New York. He was a true English gentleman, cultivated,

courteous, affable and inclined to be all things to all men. Had he

come in any

other capacity than that of royal governor he would have found life in

Boston

exceedingly agreeable. But one of his instructions was to push the

matter of

salary, and as soon as this matter was broached the people forgot that

he was

personally a delightful man. As if to avert any plea of poverty which

the House

might advance, he referred in his first address, asking for a

salary of

£1,000, to the lavish fashion in which he had been welcomed.

But this quite

failed to make those whom he would have conciliated agree to

what he demanded.

They had planted themselves once and for all where the war of the

Revolution

found them-on the position that all "impositions, taxes and

disbursements

of money were to be made by their own freewill, and not by dictation of

king,

council or parliament." We must, as George E. Ellis lucidly points out

in

his study of the royal governors, honour their pluck and

principle, while at

the same time doing justice to the "firm loyalty, the self-respect, the

dignity and persistency, with which Bur-net stood to his instructions,

nobly

rejecting as an attempt at bribery, all the evasive ingenuity of the

recusant

House in offering him three times the sum as a present, while he was

straitened

by actual pecuniary need."

The dissension which

followed after this question had been broached was harsh in the extreme

and, in

the midst of it, the governor, while driving from Cambridge to Boston

in his

carriage, was overturned on the causeway, cast into the water and so

chilled as

to be thrown into a fever from which he died on September 7, 1729. The

Bostonians seem to have realized that chagrin and excitement probably

played as

much part in hastening his end as the ducking which was the

immediate cause of

it, and they buried him with great pomp at an expense of eleven hundred

pounds.

The funeral was conducted

after the English fashion and not in the slightly mitigated

Puritan manner of

Cotton Mather's interment. (Before Mather's day there had been wont to

be no

service whatever, the company coming together at the tolling of a bell,

carrying

the body solemnly to the grave and standing by until it was covered

with earth

and that, not in consecrated ground, but in some such

enclosure by the

roadside as one sees frequently to-day in sparsely settled country

villages.)

Gloves and rings were given

to the mourning members of the General Court, and the

ministers of King's

Chapel, to three physicians, the bearers, the president of Harvard

College and

the women who laid out the body; while gloves only were given to the

under-bearers, the justices, the captains of the castle and of the man-of-war in the

harbour, to officers

of the customs, professors and fellows of the college, and the

ministers of

Boston who happened to attend the funeral. Wine in abundance

was furnished to

the Boston regiment. Apropos of Governor Burnet's funeral Mr. Arthur

Gilman

states in his readable "Story of Boston" that the distribution of

rings was common on such occasions, and until 1721. gloves and scarfs

were also

given away. But in 1741 wine and rum were forbidden to be distributed

as scarfs

had been forbidden twenty years earlier. (There had, however, been some

advance

since the time of Charles II, when on the occasion of the burying of a

lord, as

the oration was being delivered "a large pot of wine stood upon the

coffin, out of which everyone drank to the health of the deceased.")

Five years after Burnet's

death the General Court voted his orphan children three thousand pounds.

And now we come to the

appointment of Belcher, with whom this chapter opened. He was in

London, on the

Province's behalf, at the time when the news of Burnet's death

arrived and, by

the exercise of not a little diplomacy, he managed to get

himself commissioned

governor (January 8, 1730), and so was able to land in Boston from a

warship in

the autumn of that same year. He also was received with signs of

rejoicing,

accompanied by the inevitable sermon. To his credit, it should

be said, that

he alone, of the governors chosen by the king, seems to have stood

faithful to

his paternal religion. He gave the land for the Hollis Street Church,

of which

Rev. Mather Byles, Sr., was minister, and, for many years, lived

conveniently

near to this parish of which he was a patron. The house still standing

in

Cambridge, with which Belcher's name is associated, was an

inheritance from

his father and had passed out of his hands ten years before he became

governor.

Apart from the salary

matter, concerning which he of course strove with no more and no less

success

than his predecessors, Belcher's administration of eleven years was a

very

peaceable one. I have elsewhere1

given an account of the very

interesting journey that he and his Council made to Deerfield for the

purpose

of settling a grievance of the Indians in that section. The governor

lost his

wife during his term of office and the News-Letter of October 14, 1736,

obligingly describes in detail the ensuing funeral:

"The Rev. Dr. Sewall

made a very suitable prayer. The coffin was covered with black

velvet and

richly adorned. The pall was supported by the Honourable

Spencer Phipps Esq.,

our Lieutenant-Governor; William Dummer Esq., formerly Lieutenant

Governor and

Commander-in-Chief of this province; Benjamin Lynde, Esq.,

Thomas Hutchinson,

Esq., Edmund Quincy, Esq., and Adam Winthrop Esq. His Excellency, with

his

children and family followed the corpse all in deep mourning;

next went the

several relatives, according to their respective degrees, who were

followed by

a great many of the principal gentlewomen in town; after whom went the

gentlemen of His Majesty's Council; the reverend ministers of this and

the

neighbouring towns the reverend President and Fellows of

Harvard College; a

great number of officers both of the civil and military order, with a

number of

other gentlemen.

"His Excellency's coach,

drawn by four horses, was covered with black cloth and adorned with

escutcheons

of the coats of arms both of his Excellency and of his deceased lady

[She had

been the daughter of Lieutenant Governor William Partridge of

New Hampshire].

All the bells in town were tolled; and during the time of the

procession the

half minute guns begun, first at His Majesty's Castle William, which

were

followed by those on board His Majesty's ship 'Squirrel' and many other

ships

in the harbour their colors being all day raised to the heighth as

usual on

such occasions. The streets through which the funeral passed,

the tops of the

houses and windows on both sides, were crowded with innumerable

spectators."

Belcher was removed from his

post in Boston May 6, 1741, and, after an interval of four

years, was made

governor of New Jersey, where he was welcomed with open arms and did

much to

help Jonathan Edwards — in whose "Great Awakening" he had

been deeply

interested-put Princeton University on its feet. But he always retained

his

affection for his native place and he enjoined that his

remains be brought to

Cambridge and buried in the cemetery adjoining Christ Church,

in the same

grave with his cousin Judge

Remington,

who had been his ardent friend. He died August 31, 1757. He was

succeeded in

Boston by William Shirley, a man whose stay here was bound up with such

an

interesting romance that I have chosen to discuss his career along with

the

events traced in the next chapter. It must, however, be plain by now

that

Boston has advanced a long way from the prim town over which

the Mathers held

sway. Already it has become the scene and centre of a miniature court,

with the

state, the forms and the ceremonies appertaining thereto. Gold lace,

ruffled

cuffs, scarlet uniform and powdered wigs are by this time to he

encountered

everywhere on the street, and even when the governor went to the

Thursday

lecture he was richly attired and escorted by halberds. The bulk of the

people

to be sure are still thrifty mechanics, industrious and

plain-living; but

there are many persons of wealth, intelligence and culture, and these

throng

King's Chapel on Sunday. For the Brocade Age has dawned.

The Mather tomb in the Copp's Hill Burying Ground.

_________________________