| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XXI

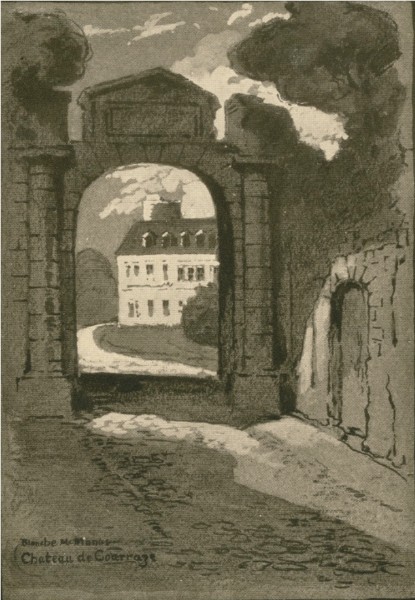

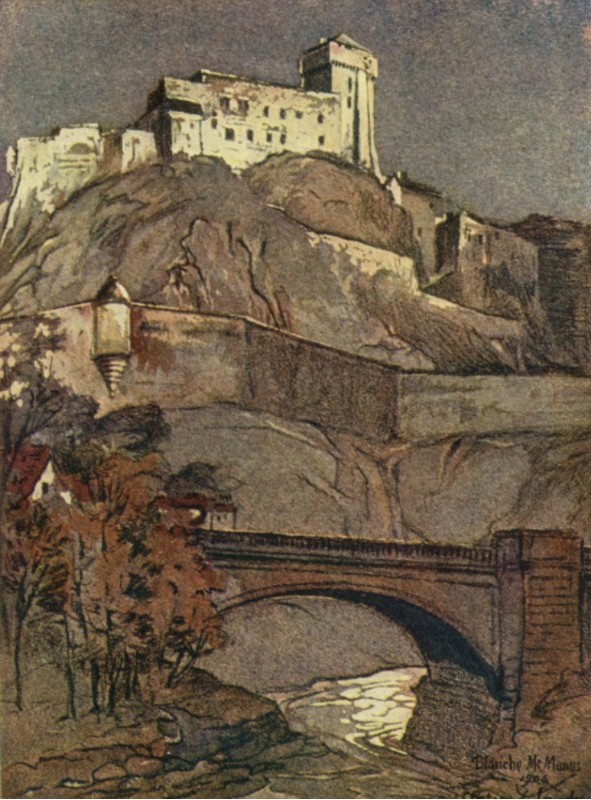

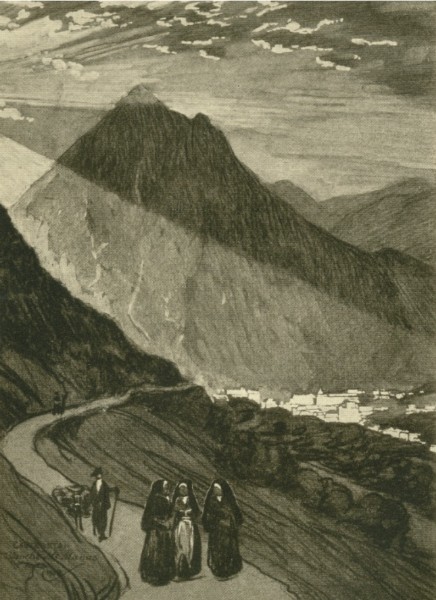

BY THE BLUE GAVE DE PAU Tux Gave de Pau, a swiftly-flowing stream which comes down from its icy cradle in the Cirque de Gavarnie and joins with the Adour near Bayonne's port, winds its way through a gentle, smiling valley filled with gracious vistas, historic sites and grand mountain backgrounds. Next to the æsthetic aspects of the Gave de Pau are its washhouses. The writer in years of French travel does not remember to have seen a stream possessed of so many. One sees similar arrangements for washing clothes all over France, but here they are exceedingly picturesque in their disposition, and the workers therein are not of the Zola-Amazon type, nor of the withered beldam class. How much better they wash than others of their fraternity elsewhere is not to be remarked. There are municipal washhouses in some of the larger towns of France, great, ugly, brick, cement and iron structures, but as the actual washing is done after the same manner as when carried on by the banks of a rushing river or a purling brook there is not much to be said in their favour that cannot as well be applied to the washhouses of Pau, Oloron or Orthez in Navarre, and artist folk will prefer the latter. Coarraze, twenty kilometres above Pau, on the banks of the Gave, is a populous centre where the hum of industry, induced by the weavers who make the toile du Béarn, is the prevailing note. Toile du Béarn and chapelets are the chief output of this little bourg, and many francs are in circulation here each Saturday night that would probably be wanting except for these indefatigable workers who had rather bend over greasy machines at something more than a living wage, than dig a mere existence out of the ground. The little bourg is dull and gray in colour, only its surroundings being brilliant. Its situation is most fortunate. Opposite is a great tree-covered plateau, a veritable terrace, on which is a modern château replacing another which has disappeared — "comme un chevreau en liberté," says the native. It was in this old Château de Coarraze that the youthful Henri IV was brought up by an aunt, en paysan, as the simple life was then called. Perhaps it was this early training that gave him his later ruggedness and rude health.  CHÂTEAU DE COARRAZE The château has been called royal, and its construction has been attributed to Henri IV, but this is manifestly not so. Only ruined walls and ramparts, and the accredited facts of history, remain to-day to connect Henri IV with the spot. The château virtually disappeared in a revolutionary fury, and only the outline of its former walls remains here and there. A more modern structure, greatly resembling the château at Pau, practically marks the site of the former establishment endowed with the memory of Henri IV's boyhood. Froissart recounts a pleasant history of the Château de Coarraze and its seigneur. A certain Raymond of Béarn had acquired a considerable heritage, which was disputed by a Catalan, who demanded a division. Raymond refused, but the Catalan, to intimidate his adversary, threatened to have him excommunicated by the Pope. Threats were of no avail, and Raymond held to his legacy as most heirs do under similar claims. One night some one knocked loudly at Raymond's door. "Who is there?" he cried in a trembling voice. "I am Orthon, and I come on behalf of the Catalan." After a parley he left, nothing accomplished, but returned night after night in some strange form of man or beast or wraith or spook or masquerader and so annoyed Raymond that he was driven into madness, the Catalan finally coming to his own. At Nay, Gaston Phœbus is said to have built a sort of modest country house which in later centuries became known simply as La Maison Carrée. Perhaps Gaston Phœbus built it, and perhaps he did not, for its architecture is f a very late Renaissance. At any rate it has a charming triple-galleried house-front, quite in keeping with the spirit of mediævalism which one associates with a builder who has "ideas" and is not afraid of carrying them out, and this was Gaston's reputation. The house is on record as having one day been occupied by the queen of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret. Just beyond Coarraze is Betharrem whose "Calvary" and church are celebrated throughout the Midi. From the fifteenth of August to the eighth of September it is a famous place of pilgrimage for the faithful of Béarn and Bigorre, a veritable New Jerusalem. Its foundation goes back to antiquity, but its origin is not unknown, if legend plays any part in truthful description. One day, too far back to give a date, a young and pious maiden fell precipitately into the Gave. She could not swim and was sinking in the waters, when she called for the protection of the Virgin Mary. At that moment a tree trunk, leaning out over the river, gave way and fell into the waters; the maiden was able to grasp it and keep afloat, and within a short space was drifted ashore. There is nothing very unplausible about this, nothing at all miraculous; and so it may well be accepted as a legend based on truth. A modest chapel was built near at hand, by some pious folk, to commemorate the event, or perhaps it was built — as has been claimed — by Gaston IV himself, on his return from the Crusades in the middle of the twelfth century. The latter supposition holds good from the fact that the place bears the name of the city by the Jordan. Montgomery burned the chapel during the religious wars, but again in the seventeenth century, Hubert Charpentier, licencié of the Sorbonne, came here and declared that the configuration of the mountain resembled that where took place the crucifixion, and accordingly erected a Calvary dedicated to "Our Lady," "in order," as he said, "to revivify the faith which Calvinism had nearly extinguished." Saint-Pé-de-Bigorre, lying midway between Pau and Lourdes, is an ideally situated, typical small town of France. It is not a resort in any sense of the word, but might well be, for it is as delightful as any Pyrenean "station" yet "boomed" as a cure for the ills of folk with imaginations. It is a genuine garden-city. Its houses, strung out along the banks of the Gave, are wall-surrounded and tree-shaded, nearly every one of them. But one hotel extends hospitality at Saint Pé to-day, but soon there will be a dozen, no doubt, and then Saint Pé will be known as a centre where one may find "all the attractions of the most celebrated watering-places." To-day Saint Pé depends upon its ravishing site and its historic past for its reason for being. It derives its name from the old Abbey of Saint-Pé-de-Générès (Sanctus Petrus de Generoso), founded here in the eleventh century, by Sanchez-Guillaume, Duc de Gascogne, in commemoration of a victory. This monastery, with its abbatial church, was razed during the religious wars by the alien Montgomery who outdid in these parts even his hitherto unenviable cruelties. The church was built up anew, from such of its stones as were left, into the present edifice which serves the parish, but nothing more than the tower and the apse are of the original structure. To Lourdes is but a dozen kilometres by road or rail from Saint Pé. In either case one follows along the banks of the Gave with delightful vistas of hill and dale at every turn, and always that blue-purple curtain of mountains for a background. Lourdes is perhaps the most celebrated, if not the most efficacious, pilgrim-shrine in all the world. It's a thing to see, if only to remark the contrasting French types among the pilgrims that one meets there — the Breton from Pont Aven or Quimperlé, the Norman from the Pays de Caux, the Parisian, the Alsaçien, the Niçois and the Tourangeau. All are here, in all stages of health and sickness, vigorous and crippled. The shrine of "Our Lady of Lourdes" is all things to all men. Lourdes is a beastly, unclean, and uncomfortable place in which to linger, in spite of its magnificent situation, and its great and small hotels with all manner of twentieth-century conveniences. It's a plague-spot on fair France, looking at it from one point of view; and a living superstition of Christendom from another. The medical men of France want to close it up; the churchmen and hotel keepers want to keep it. open. Arguments are puerile, so there the matter stands; and neither side has gained an appreciable advantage over the other as yet. Lourdes was one day the capital of the ancient seigneurie, Lavedan-en-Bigorre, and at that time bore the name Mirambel, which in the patois of the region signified beautiful view. Originally it was but a tiny village seated at the foot of a rock, and crowned by the same château which exists to-day, and which in its evolution has come down from a castellum-romain, a Carlovingian bastille, a Capetian and English prison of state, a hospital for the military, a barracks, to finally being a musée. Of the château of the feudal epoch nothing remains, save two covered ways, the donjon, a sixteenth-century gate and a drawbridge, this latter probably restored out of all semblance to its former outlines. One of these covered ways gave access to the upper stages with so ample a sweep that it became practically a horse stairway upon which cavaliers and lords and ladies reined their chargers.  CHÂTEAU DE LOURDES The donjon is manifestly a near relation to that of Gaston Phœbus at Foix, though that prince had no connection with the château. Transformation has changed all but its outlines, its fosse has become a mere sub-cellar, and its windows have lost their original proportions. The Château de Lourdes was undoubtedly a good defence in its day in spite of its present attenuated appearance. In 1373 it resisted the troops of Charles V, commanded by the Duc d'Anjou. Under the ancient French monarchy its career was most momentous, though indeed merely as a prison of state, or a house of detention for political suspects. Many were the "lettres de cachet" that brought an unwilling prisoner to be caged here in the shadow of the Pyrenees, as if imbedded in the granite of the mountains themselves. The rock which supports the château rises a hundred metres or so above the Gave. A great square mass — the donjon — forms the principal attribute, and was formerly the house of the governor. This donjon with a chapel and a barracks has practically made up the ensemble in later years. Here, on one of the counterforts of the Pyrenees, just beyond the grim old château, and directly before the celebrated Pic du Ger, now desecrated by a cog-railway, where the seven plains of Lavedan blend into the first slopes of the mountains, were laid the first stones of the Basilique de Lourdes in 1857. Previously the site was nothing more than a moss-grown grotto where trickled a fountain that, for ages, had been the hope of the incurably ill, who thought if they bathed and drank and prayed that miracles would come to them and they would be made whole again. The fact that the primitive, devout significance of this sentiment has degenerated into the mere pleasure seeking of a mixed rabble does not affect in the least the simple faith of other days. The devout and prayerful still come to bathe and pray, but they are lost in the throng of indiscriminately "conducted" and "non-conducted" tourists who make of the shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes a mere guide-book sight to be checked off the list with others, such as the Bridge of Sighs, the Pyramids of Gizeh, the Tour Eiffel, or Hampton Court, — places which once seen will never again be visited. To-day only the smaller part of the visitors, among even the French themselves, excepting the truly devout, who are mostly Bretons — will reply to the question as to whether they believe in Lourdes: "Oui, comme un article de foi." No further homily shall be made, save to say that the general aspect of the site is one of the most picturesque and enchanting of any in the Pyrenees — when one forgets, or eliminates, the signs advertising proprietary condiments and breakfast foods. It doesn't matter in the least whether one Frenchman says: "C'est ma Foi;" or another "C'est un scandale;" the landscape is gloriously beautiful. Of the Grotto itself one can only remark that its present-day garnishings are blatant, garish and offensive. The great, slim basilica rises on its monticule as was planned. It has been amply endowed and extravagantly built. Before it is a perron, or more properly a scala-sancta, and the whole is so theatrically disposed, with a great square before it, that one can quite believe it all a stage-setting and nothing more. As a place of pilgrimage, Lourdes is perhaps the most popular in all the world, certainly it comes close after Jerusalem and Rome. Alphonse XIII, the present ruler of Spain, made his devotions here in August, 1905. Argelès is practically a resort, and has the disposition of a Normandy village; that is, its houses are set about with trees and growing verdure of all sorts. For this reason it is a delightful garden city of the first rank. Argelès' chief attraction is its site; there are no monuments worth mentioning, and these are practically ruins. Argelès is a watering-place pure and simple, with great hotels and many of them, and prices accordingly. Above Argelès the Gave divides, that portion to the left taking the name of Gave de Cauterets, while that to the right still retains the name of Gave de Pau. Cauterets has, in late years, become a great resort, due entirely to its waters and the attendant attractions which have grouped themselves around its établissement. The beneficial effect of the drinking or bathing in medicinal waters might be supposed to be somewhat negatived by bridge and baccarat, poker and "petits chevaux" but these distractions — and some others — seem to be the usual accompaniments of a French or German spa. "C'est le premier jour de septembre que les bains des Pyrénées commencent à avoir de la vertu." Thus begins the prologue to Marguerite de Navarre's "Heptameron." The "season" to-day is not so late, but the queen of Navarre wrote of her own experiences and times, and it is to be presumed she wrote truly.  CAUTERETS A half a century ago Cauterets was a dirty, shabby village, nearly unknown, but the exploiter of resorts got hold of it, and with a few medical endorsements forthwith made it the vogue until now it is as trim and well-laid-out a little town as one will find. The town is a gem of daintiness, in strong contrast to the surrounding melancholy rocks and forests of the mountainside. Peaks,. approximating ten thousand feet in height, rise on all sides, and dominate the more gentle slopes and valleys, but still the general effect is one of a savage wildness, with which the little white houses of the town, the electric lights and the innumerable hotels — a round score of them — comport little. Certainly the beneficial effects accruing to semi-invalids here might be supposed to be great — if they would but leave "the game" alone. A simple mule path leads to the Col de Rion back of Cauterets, though it is more frequented by tourists on foot than by beasts of burden. Here on the Col itself, in plain view of the Pic du Midi and its sister peaks, the Touring Club has erected one of those admirable guidebook accessories, a "table d'orientation." On its marbled circumference are traced nearly three hundred topographical features of the surrounding landscape, and a study of this well-thought-out affair is most interesting to any traveller with a thought above a table d'hôte. Throughout the region of the Pyrenees these circular "tables d'orientation," with the marked outlines of all the surrounding landscape, are to be found on many vantage grounds. The principal ones are: — On

the Ramparts of the Château de Pau.

The Col d'Aspin. The Col de Riou. Platform of the Tour Massey at Tarbes. Platform de Mouguerre. Summit of the Pic du Midi. Summit of the Cabaliros. Summit of the Canigou. Over the Col de Riou and down into the Gave de Pau again, and one comes to Luz. Luz is curiously and delightfully situated in a triangular basin formed by the water-courses of the Gave de Pau and the Gave de Barèges. Practically Luz is a ville ancienne and a ville moderne, the older portion being by far the most interesting, though there is no squalor or unusual picturesqueness. Civic improvements have straightened out crooked streets and razed tottering house fronts and thus spoiled the picture of mediævalism such as artists — and most others — love. A ruined fortress rises on a neighbouring hill-top which gives a note of feudal times, but the general aspect of Luz, and its neighbouring pretty suburb of St. Sauveur, each of them possessed of thermal establishments, are resorts pure and simple, which, indeed, both these places were bound to become, being on the direct route between Pau and Tarbes and Gavarnie, and neighbours of Cauterets and Barèges. Barèges lies just eastward of Luz on a good carriage road. Like Bagnères-de-Bigorre, it is an oddly named town which depends chiefly upon the fact that it is a celebrated thermal station for its fame. It sits thirteen hundred metres above the sea, and while bright and smiling and gracious in summer, in winter it is as stern-visaged as a harpy, and about as unrelenting towards one's comfort. Only this last winter the mountain winds and snows caved in Barèges' Casino and a score of houses, killing several persons. There is no such a storm-centre in the Pyrenees. Barèges has got a record no one will envy, though the efficacy ' of its waters makes them worthy rivals of those of Bigorre and Cauterets. The fame of Barèges' waters goes back to the days of the young Duc du Maine, who came here with Madame de Maintenon, in 1667, on the orders of the doctor of the king. In 1760 a military hospital was founded here to receive the wounded of the Seven Years War. Barèges is one of the best centres for mountain excursions in the Pyrenees. The town itself is hideous, but the surroundings are magnificent. Above Saint Sauveur, Luz and Cauterets, in the valley of the Gaube, rises the majestic Vignemale, whose extreme point, the Pic Longue, reaches a height of three thousand, two hundred and ninety-eight metres, which is the greatest height of the French Pyrenees. In the year 1808, on the occasion of the coming of the Queen of Holland, spouse of Louis Bonaparte, to the Bains de Saint Sauveur, an unknown muse of poesy sang the praise of this great mountain as follows:- "Roi

des Monts: Despote intraitable.

Toi qui domine dans les airs, Toi dont le trône inabordable Appelle et fixe les éclairs! Fier Vignemale, en vain ta cime S'entoure d'un affreux abime De niège et de débris pierreux; Une nouvelle Bérénice Ose, à côts du précipice, Gravir sur ton front sourcilleux!" Each of the thermal stations in these parts possesses its own special peak of the Pyrenees. Luchon has the Nethou; Bigorre the Pic du Midi de Bagnères; Eaux-Bonnes the Balaitous; Eaux-Chaudes the Pic du Midi d'Ossau; Vernet the Canigou and Saint Sauveur and Cauterets the Vignemale. The Vignemale, composed of four peaks, each of them overreaching three thousand, two hundred metres, encloses a veritable river of ice. Its profound crevasses and its Mer de Glace remind one of the Alps more than do the accessories of any other peak of the Pyrenees. The ascension of the Vignemale, from Cauterets or Luz, is the classic mountain climb of the Pyrenees. No peak is more easy of access, and none gives so complete an idea of the ample ranges of the Pyrenees, from east to west, or north to south. |