| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

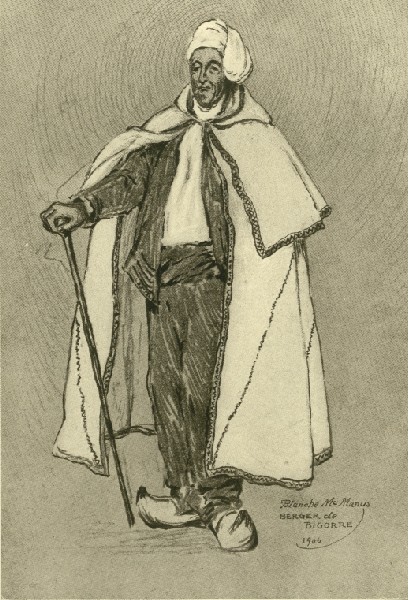

| CHAPTER .XX

TARBES, BIGORRE AND LUCHON THERE is a clean-cut, commercial-looking air to Tarbes, little in keeping with what one imagines the capital of the Hautes-Pyrénées to be. Local colour has mostly succumbed to twentieth-century innovations in the train of great hotels, tourists and clubs. In spite of this, the surrounding panorama is superb; the setting of Tarbes is delightful; and at times — but not for long at a time — it is really a charming town of the Midi. Tarbes possessed a château of rank long years ago; not of so high a rank as that of Pau, for that was royal, but still a grand and dignified château, worthy of the seigneurs who inhabited it. Raymond I fortified the place in the tenth century, and all through the following five hundred years life here was carried on with a certain courtly splendour. To-day the château, or what is left of it, serves as a prison. The unlovely cathedral at Tarbes was once a citadel, or at least served as such. It must have been more successful as a warlike accessory than as a religious shrine, for it is about the most ungracious, unchurchly thing to be seen in the entire round of the Pyrenees. The chief architectural curiosity of Tarbes is the Lycée, on whose portal (dated 1669) one reads: "May this building endure until the ant has drunk the waters of the ocean, and the tortoise made the tour of the globe." It seems a good enough dedication for any building. The ever useful Froissart furnishes a reference to Tarbes and its inns which is most apropos. Travellers even in those days, unless they were noble courtiers, repaired to an inn as now. The Messire Espaing de Lyon, and the Maître Jehan Froissart made many journeys together. It was here under the shelter of the Pyrenees that the maître said to his companion: "Et nous vînmes à Tarbes, et nous fûmes tout aises à l'hostel de l'Etoile.... C'est une ville trop bien aisée pour séjourner chevaux: de bons foins, de bons avoines et de belles rivières." Tarbes is something of an approach to this, but not altogether. The missing link is the Hostel de l'Étoile, and apparently nothing exists which takes the place of it. From the fourteenth century to the twentieth century is a long time to wait for hotel improvements, particularly if they have not yet arrived. The great Marché de Tarbes is, and has been for ages, one of its chief sights, indeed it is the rather commonplace modern city's principal picturesque accessory, if one excepts its grandly scenic background. Every fifteen days throughout the year the market draws throngs of buyers and sellers from the whole region of the western Pyrenees. In the very midst of the most populous and wealthy valleys and plains of the Pyrenees, one sees here the complete gamut of picturesque peoples and costumes in which the country abounds. Here are the Béarnais, agile and gay, and possessed of the very spirit associated with Henri IV. They seat themselves among their wares, composed of woollen stuffs and threads, pickled meats, truffles, potatoes, cheeses of all sorts, agricultural implements — mostly primitive, but with here and there a gaudy South Bend or Milwaukee plough — porcelain, coppers, cattle, goats, sheep and donkeys, and a greater variety of things than one's imagination can suggest. It is almost the liveliest and most populous market to be seen in France to-day. The gaudy umbrellas and tents cover the square like great mushrooms. There are much picturesqueness and colour, and lively comings and goings too. This is ever a contradiction to the reproach of laziness usually applied to the care-free folk of the Midi. In olden times the market of Tarbes was the resort of many Spanish merchants, and they still may be distinguished as donkey-dealers and mule traders, but the chief occupants of the stalls and little squares of ground are the dwellers of the countryside, who think nothing of coming in and out a matter of four or five leagues to trade a side of bacon — which they call simply salé — for a sheep or a goat, or a sheep or a goat for a nickel clock, made in Connecticut. It's as hard for the peasant to draw the line between necessities and superfluities as it is for the rest of us, and he is often apt to put caprice before need. Neighbouring close upon Tarbes is the ancient feudal bourg of Ossun, which most of the fox-hunters of Pau, or the pilgrims of Lourdes, know not even by name. It's only the traveller by road-the omnipresent automobilist of to-day — who really stands a chance of "discovering" anything. The art of travel degenerated sadly with the advent of the railway and the "personally conducted pilgrimage," but the automobile is bringing it all back again. The bicycle stood a chance of participating in the same honour at one time, but folk weren't really willing to take the trouble of becoming a vagabond on wheels. Ossun was the site of a Roman camp before it became a feudal stronghold, and with the coming of the château and its seigneurs, in the fifteenth century, it came to a prominence and distinction which made of it nearly a metropolis. To-day it is a dull little town of less than two thousand souls, but with a most excellent hotel, the Galbar, which is far and away better (to some of us) than the popular hotels of Pau, Tarbes or Luchon. The château of Ossun, or so much of it as remains, was practically a fortress. What it lacks in luxury it makes up for in its intimation of strength and power, and from this it is not difficult to estimate its feudal importance. The Roman camp, whose outlines are readily defined, was built, so history tells, by one Crassus, a lieutenant of Cæsar. It was an extensive and magnificent work, a long, sunken, oblong pit with four entrances passing through the sloping dirt walls. Four or five thousand men, practically a Roman legion, could be quartered within. It was from the Château d'Odos, near Tarbes, in the month of December, 1549, that the Queen of Navarre observed the comet which was said to have made its appearance because of the death of Pope Paul III. Says Brantome: "She jumped from her bed in fright at observing this celestial phenomenon, and presumably lingered too long in the chill night, for she caught a congestion which brought about her death eight days later, 21st December, 1549, in the fifty-eighth year of her age." According to Hilarion de Coate her remains were transported to Pau, and interred in the "principal église," but others, to the contrary, say that she was buried in the great burial vault at Les-car. This is more likely, for an authentic document in the Bibliothèque Nationale describes minutely the details of the ceremony of burial "dans l'antique cathédrale de Lescar." On the Landes des Maures, near by, was celebrated a bloody battle in the eighth century between the Saracens and the inhabitants of the country. Gruesome finds of "skulls of extraordinary thickness" have frequently been made on this battlefield. Just what this description seems to augur the writer does not know; perhaps some ethnologist who reads these lines will. At any rate the combatants must have died hard.  A SHEPHERD OF BIGORRE Following up the valley of the Adour one comes to the Bagnères de Bigorre in a matter of twenty-five kilometres or so. Bagnères de Bigorre is a hodge-podge of a name, but it is the "Bath" of France, as an Englishman of a century ago called it. There are other resorts more popular and fashionable and more wickedly immoral, such as Vichy, Aix les Bains and even Luchon, but still Bigorre remains the first choice. From the times of the Romans, throngs have been coming to this charming little spot of the Pyrenees where the mineral waters bubble up out of the rock, bringing health and strength to those ill in mind and body. Pleasure seekers are here, too, but primarily it is the baths which attract. There are practically no monuments of bygone days here, but fragmentary relics of one sort or another tell the story of the waters from Roman times to the present with scarcely a break. Arreau, seven leagues from Bigorre, towards the heart of the Pyrenees, through the Val d'Arreau, certainly one of the most picturesquely unspoiled places in all the Pyrenees, is a relic of mediævalism such as will hardly be found elsewhere in the whole chain of mountains from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. Its feudal history was fairly important, but its monuments of the period, save its churches and its market house or "Halle," have practically disappeared. Whatever defences there may have been, have been built into the town's fine stone houses and bridges, but the Roman tower of St. Exupère, and the primitive church now covered by Notre Dame show its architectural importance in the past. By reason of being one of the gateways through the Pyrenees into Spain (by the valley of the Arreau and the portes, so called, of Plan and Vielsa) Arreau enjoys a Franco-Espagnol manner of living which is quaint beyond words. It is the nearest thing to Andorra itself to be found on French soil. Luchon is situated in a nook of the Larboust surrounded with a rural beauty only lent by a river valley and a mountain background. The range to the north is bare and grim, but to the southward is thickly wooded, with little eagles'-nest villages perched here and there on its flanks and peaks, in a manner which leads one to believe that this part of the Pyrenees is as thickly peopled as Switzerland, where peasants fall out of their terrace gardens only to tumble into those of a neighbour living lower down the mountain-side. The surroundings of Luchon are indeed sublime, from every point of view, and one's imagination needs no urging to appreciate the sentiment which is supposed to endow a "nature-poet." Yes, Luchon is beautiful, but it is overrun with fashionables from all over the world, and is as gay as Biarritz or Nice. "La grande vie mondaine" is the key-note of it all, and if one could find out just when was the off-season it would be delightful. Of late it has been crowded throughout the year, though the height of fashion comes in the spring. Outside of its sulphur springs the great world of fashion comes here to dine and wine their friends and play bridge. Luchon has a history though. As a bathing or a drinking place it was known to the Romans as Onesiorum Thermæ and was mentioned by Strabo as being famous in those days. There were many pagan altars and temples here erected to the god Ilixion, which by evolution into Luchon came to be the name by which the place has latterly been known. In 1036, by marriage, Luchon was transferred from the house of Comminges to that of Aragon, but later was returned to the Comtes de Comminges and finally united with France in 1458 under Charles VII, retaining, however, numerous ancient privileges which endured until the end of the seventeenth century. This was the early history of Luchon. Its later history began when, in 1754, the local waters were specially analyzed and a boom given to a project to make of the place a great spa. The city itself is the proprietor of all the springs and its administrative sagacity has been such that fifty thousand visitors are attracted here within the year. |