| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

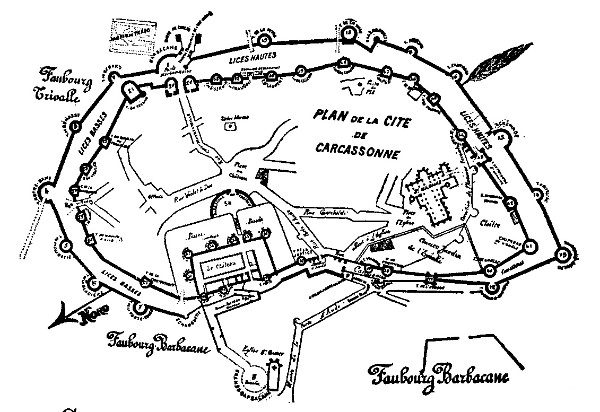

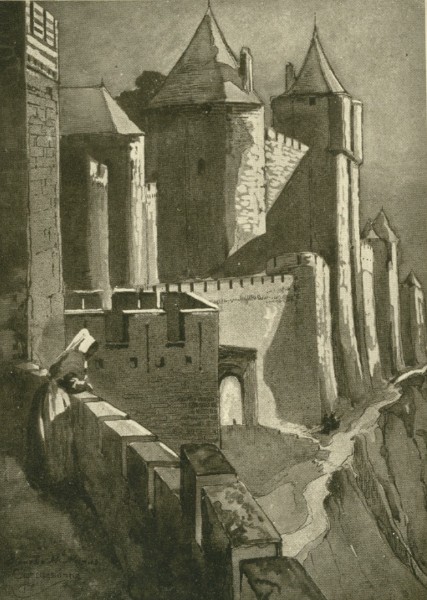

| CHAPTER IX

THE WALLS OF CARCASSONNE NEVER was there an architectural glory like that of Carcassonne. Most mediæval fortified bourgs have been transformed out of all semblance to their former selves, but not so Carcassonne. It lives to-day as in the past, transformed or restored to be sure, but still the very ideal of a walled city of the Middle Ages. The stress and cares of commerce and the super-civilization of these latter days have built up a new and ugly commercial city beyond the walls, leaving La Cité a lonely dull place where the very spirit of mediævalism stalks the streets and passages, and the ghosts of a past time people the château, the donjon, and the surrounding buildings which once sheltered counts and prelates and chevaliers and courtly ladies. The old cathedral, too, dedicated to St. Nazaire, a s pure a Gothic gem as may be found outside Sainte Chapelle in Paris, is as much of the past as if it existed only in memory, for services are now carried on in a great, gaunt church in the lower town, leaving this magnificent structure unpeopled and alone. Carcassonne, as seen from the low-lying plain of the valley of the Aude, makes a most charming motif for a picture. In the purple background are the Pyrenees, setting off the crenelated battlements of walls, towers and donjon in genuine fairy-land fashion. It is almost too ethereal to be true, as seen through the dim mist of an early May morning. "A wonderful diadem of chiselled stone set in the forehead of the Pyrenees," an imaginative Frenchman called it. It would not be wise to attempt to improve on this metaphor. This world's wonder — for it is a world's wonder, though not usually included in the magic seven — has enchanted author, poet, painter, historian and architect. Who indeed could help giving it the homage due, once having read Viollet-le-Duc's description in his "Dictionnaire Raisonée d'Architecture," or Nadaud's lines beginning: — "Je n'ai jamais vu Carcassonne." Five thousand people from all over the world pass its barbican in a year, and yet how few one recalls among his acquaintances who have ever been there. It began to dawn upon the French away back in 1835, at the instigation of Prosper Merimée, that they had within their frontiers the most wonderfully impressive walled city still above ground. It was the work of fifty years to clear its streets and ramparts of a conglomerate mass of parasite structures which had been built into the old fabric, and to reconstruct the roofings and copings of walls and houses to an approximation of what they must once have been. Carcassonne is not very accessible to the casual tourist to southern France who thinks to laze away a dull November or January at Pau, Biarritz, or even on the Riviera. It is not in the least inaccessible, but it is not on the direct line to anywhere, unless one is en route from Bordeaux to Marseilles, or is making a Pyrenean trip. At any rate it is the best value for the money that one will get by going a couple of hundred kilometres out of his way in the whole circuit of France. By all means study the map, gentle reader, and see if you can't figure it out somehow so that you may get to Carcassonne. Carcassonne, the present city, dates from the days of the good Saint Louis, but all interest lies with its elder sister, La Cité, a bouquet of walls and towers, just across the eight-hundred-year-old bridge over the Aude. Close to the feudal city, across the Pont-Vieux, was the barbican, a work completed under Saint Louis. It gave immediate access to the city of antiquity, and defended the approaches to the château after the manner of an outpost, which it really was. This one learns from the Old plans, ' but the barbican itself disappeared in 1816.  PLAN OF CARCASSONNE Carcassonne was a most effective stronghold and guarded two great routes which passed directly through it, one the Route de Spain, and the other running from Toulouse to the Mediterranean, the same that scorching automobilists "let out" on to-day as they go from one gaming-table at Monte Carlo to another at Biarritz. The Romans first made Carcassonne a stronghold; then, from the fifth to the eighth centuries, came the Visigoths. The Saracens held it for twenty-five years and their traces are visible to-day. After the Saracens it came to Charlemagne, and at his death to the Vicomtes de Carcassonne, independent masters of a neighbouring region, who owed allegiance to nobody. This was the commencement of the French dynasty of Trencavel, and the early years of the eleventh century saw the court of Carcassonne brilliant with troubadours, minstrels and Cours d'Amour. The Cours d'Amour of Adelaide, wife of Roger Trencavel, and niece of the king of France, were famous throughout the Midi. The followers in her train — minstrels, troubadours and lords and ladies — were many, and no one knew or heard of the fair chatelaine of Carcassonne without being attracted to her. Simon de Montfort pillaged Carcassonne when raiding the country round about, but meanwhile the old Cité was growing in strength and importance, and many were the sieges it underwent which had no effect whatever on its walls of stone. All epochs are writ large in this monument of mediævalism. Until the conquest of Roussillon, Carcassonne's fortress held its proud position as a frontier stronghold; then, during long centuries, it was all but abandoned, and the modern city grew and prospered in a matter-of-fact way, though never approaching in the least detail the architectural magnificence of its hill-top sister. The military arts of the Middle Ages are as well exemplified at Carcassonne as can anywhere be seen out of books and engravings. The entrance is strongly protected by many twistings and turnings of walled alleys, producing a veritable maze. The Porte d'Aude is the chief entrance, and is accessible only to those on foot. Verily, the walls seem to close behind the visitor as he makes his way to the topmost height, up the narrow cobble-paved lanes. Four great gates, one within another, and four walls have to be passed before one is properly within the outer defences. To enter the Cité there is yet another encircling wall to be passed. Carcassonne is practically a double fortress; the distance around the outer walls is a kilometre and a half and the inner wall is a full kilometre in circumference. Between these fortifying ramparts unroll the narrow ribbons of roadway which a foe would find impossible to pass.  THE WALLS OF CARCASSONNE Finally, within the last line of defence, on the tiny wall-surrounded plateau, rises the old Château de Trencavel, its high coiffed towers rising into the azure sky of the Midi in most spectacular fashion. On the crest of the inner wall is a little footpath, known in warlike times as the chemin de ronde, punctuated by forty-eight towers. From such an unobstructed balcony a marvellous surrounding panorama unrolls itself; at one's feet lie the plain and the river; further off can be seen the mountains and sometimes the silver haze shimmering over the Mediterranean fifty miles away. Centuries of civilization are at one's hand and within one's view. A curious tower — one of the forty-eight — spans the two outer walls. It is known as the Tour l'Évêque and possesses a very beautiful glass window. Here Viollet-le-Duc established his bureau when engaged on the reconstruction of this great work. Almost opposite, quite on the other side of the Cité, is the Porte Narbonnaise, the only way by which a carriage may enter. One rises gently to the plateau, after first passing this monumental gateway, which is flanked by two towers. Over the Porte Narbonnaise is a rude stone figure of Dame Carcas, the titular goddess of the city. Quaint and curious this figure is, but possessed of absolutely no artistic aspect. Below it are the simple words, "Sum Carcas." The Tour Bernard, just to the right of the Porte Narbonnaise, is a medieval curiosity. The records tell that it has served as a chicken-coop, a dog-kennel, a pigeon loft, and as the habitation of the guardian who had charge of the gate. Here in the walls of this great tower may still be seen solid stone shot firmly imbedded where they first struck. The next tower, the Tour de Benazet, was the arsenal, and the Tour Notre Dame, above the Porte de Rodez, was the scene of more than one "inquisitorial" burning of Christians. The second line of defence and its towers is quite as curiously interesting as the first. From within, the Porte Narbonnaise was protected in a remarkable manner, the Château Narbonnaise commanding with its own barbican and walls every foot of the way from the gate to the château proper. Besides, there were iron chains stretched across the passage, low vaulted corridors, wolf-traps (or something very like them) set in the ground, and loopholes in the roofs overhead for pouring down boiling oil or melted lead on the heads of any invaders who might finally have got so far as this. The château itself, so safely ensconced within the surrounding walls of the Cité, follows the common feudal usage as to its construction. Its outer walls are strengthened and defended by a series of turrets, and contain within a cour d'honneur, the place of reunion for the armour-knights and the contestants in the Courts of Love. On the ground floor of this dainty bit of mediævalism — which looks livable even to-day — were the seigneurial apartments, the chapel and various domestic offices. Beneath were vast stores and magazines. A smaller courtyard was at the rear, leading to the fencing-school and the kitchens, two important accessories of a feudal château which seem always to go side by side. On the first and second floors were the lodgings of the vicomtes and their suites. The great donjon contained a circular chamber where were held great solemnities such as the signing of treaties, marriage acts and the like. To the west of the cour d'honneur were the barracks of the garrison. All the paraphernalia and machinery of a great mediæval court were here perfectly disposed. Verily, no such story-telling feudal château exists as that of the Château de Narbonnais of the Trencavels in the old Cité of Carcassonne. The. Place du Château, immediately in front, was a general meeting-place, while a little to the left in a smaller square has always been the well of bubbling spring-water which on more than one occasion saved the dwellers within from dying of thirst. Perhaps, as at Pompeii, there are great treasures here still buried underground, but diligent search has found nothing but a few arrowheads or spear heads, some pieces of money (money was even coined here) and a few fragments of broken copper and pottery utensils. Finally, to sum up the opinion of one and all who have viewed Carcassonne, there is not a city in all Europe more nearly complete in ancient constructions, or in better preservation, than this old mediæval Cité. Centuries of history have left indelible records in stone, and they have been defiled less than in any other mediæval monument of such a magnitude. Gustave Nadaud's lines on Carcassonne come very near to being the finest topographical verses ever penned. Certainly there is no finer expression of truth and sentiment with regard to any architectural monument existing than the simple realism of the speech of the old peasant of Limoux: — "I'm

sixty years; I'm getting old;

I've done hard work through all my life, Though yet could never grasp and hold My heart's desire through all my strife. I know quite well that here below All one's desires are granted none; My wish will ne'er fulfilment know, I never have seen Carcassonne." "'They say that all the days are there As Sunday is throughout the week: New dress, and robes all white and fair Unending holidays bespeak.' "'O! God, O! God, O! pardon me, If this my prayer should'st Thou offend! Things still too great for us we'd see In youth or near one's long life end. My wife once and my son Aignan, As far have travelled as Narbonne, My grandson has seen Perpignan, But I have not seen Carcassonne."' What emotion, what devotion these lines express, and what a picture they paint of the simple faiths and hopes of man. He never did see Carcassonne, this old peasant of Limoux; the following lines tell why: — "Thus

did complain once near Limoux

A peasant hard bowed down with age. I said to him, 'My friend, we'll go Together on this pilgrimage.' We started with the morning tide; But God forgive. We'd hardly gone Our road half over, ere he died. He never did see Carcassonne." In August, 1898, a great fête and illumination was given in the old Cité de Carcassonne. All the illustrious Languedoçians alive, it would seem, were there, including the Cadets de Gascogne, among them Armand Sylvestre, D'Esparbès, Jean Rameau, Emil Pouvillon, Benjamin Constant, Eugene Falguière, Mercier, Jean-Paul Laurens, et als. All the artifice of the modern pyrotechnist made of the old city, at night, a reproduction of what it must have been in times of war and stress. It was the most splendid fireworks exhibition the world has seen since Nero fiddled away at burning Rome. "La Cité Rouge," Sylvestre called it. "Oh, l'impression inoubliable! Oh! le splendide tableau! It was so perfectly beautiful, so completely magnificent! I have seen the Kremlin thus illuminated; I have seen old Nuremberg under the same conditions, but I declare upon my honour never have I seen so beautiful a sight as the illuminations of Carcassonne." One view of the Cité not often had is from the Montagne Noire, where, from its supreme height of twelve hundred metres (the Pic de Nore) there is to be seen such a bird's-eye view as was never conceived by the imagination. On the horizon are the blue peaks of the Pyrenees cutting the sky with astonishing clearness; to the eastward is the Mediterranean; and northwards are the Cevennes; while immediately below is a wide-spread plain peopled here and there with tiny villages and farms all clustering around the solid walls of Carcassonne — the Ville of to-day and the Cité of the past. Over the blue hills, southward from Carcassonne, lies Limoux. Limoux is famous for three things, its twelfth-century church, its fifteenth-century bridge and its "blanquette de Limoux," less ancient, but quite as enduring. If one's hunger is ripe, he samples the last first, at the table d'hôte at the Hotel du Pigeon. "Blanquette de Limoux" is simply an ordinarily good white, sparkling wine, no better than Saumur, but much better than the hocks which have lately become popular in England, and much, much better than American champagne. The town itself is charming, and the immediate environs, the peasants' cottages and the vineyards, recall those verses of Nadaud's about that old son of the soil who prayed each year that he might make the journey over the hills to Carcassonne (it is only twenty-four kilometres) and refresh his old eyes with a sight of that glorious medieval monument. North of Carcassonne, between the city and the peak of the Montagne Noire, is the old château of Lastours, a ruined glory of the days when only a hill-top situation and heavy walls meant safety and long life. |