| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER VIII

THE HIGH VALLEY OF THE AUDE THE Aude, rising close under the crest of the Pyrenees, flows down to the Mediterranean between Narbonne and Béziers. It is one of the daintiest mountain streams imaginable as it flows down through the Gorges de St. Georges and by Axat and Quillan to Carcassonne, and the following simple lines by Auguste Baluffe describe it well. "Dans

le fond des bleus horizons,

Les villages ont des maisons Toutes blanches, Que l'on aperçoit à travers Les bois, formant des rideaux verts De leurs branches." At Carcassonne the Aude joins that natural waterway of the Pyrenees, the Garonne, through the Canal du Midi. This great Canal-de-Deux-Mers, as it is often called, connecting with the Garonne at Toulouse, joins the Mediterranean at the Golfe des Lions, with the Atlantic at the Golfe de Gascogne, and serves in its course Carcassonne, Narbonne and Béziers. The Canal du Midi was one of the marvels of its time when built (1668), though it has since been superseded by many others. It was one of the first masterpieces of the French engineers, and may have been the inspiration of De Lesseps in later years. Boileau in his "Epitre au Roi," said: — "J'entends

déjà fremir les deux mers étonnées

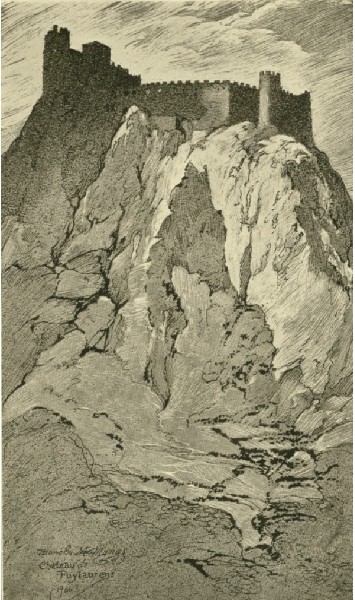

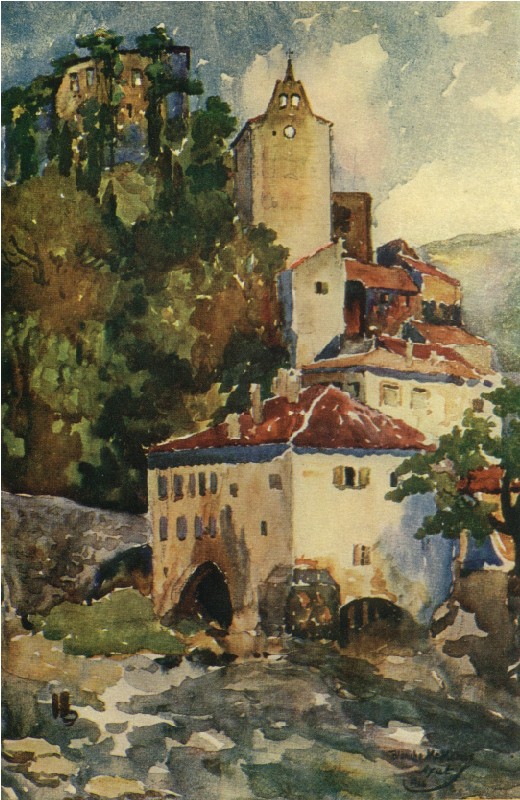

De voir leurs flots unis au pied de Pyrénées." South of Carcassonne and Limoux, just over "the mountains blue" of which the old peasant sang, is St. Hilaire, the market town of a canton of eight hundred inhabitants. It is more than that. It is a mediæval shrine of the first rank; for it is the site of an abbey founded in the fifth or sixth century. This abbey was under the direct protection of Charlemagne in 780, and he bestowed upon it "lettres de sauvegarde," which all were bound to respect. The monastery was secularized in 1748, but its thirteenth-century church, half Romanesque and half Gothic, will ever remain as one of the best preserved relics of its age. For some inexplicable reason its carved and cut stone is unworn by the ravages of weather, and is as fresh and sharp in its outlines as if newly cut. Within is the tomb of St. Hilaire, the first bishop of Carcassonne. The sculpture of the tomb is of the ninth century, and it is well to know that the same thing seen in the Musée Cluny at Paris is but a reproduction. The original still remains here. The fourteenth-century cloister is a wonderful work of its kind, and this too in a region where this most artistic work abounds. One's entrance into Quillan by road is apt to be exciting. The automobile is no novelty in these days; but to run afoul of a five kilometre procession of peasant folk with all their traps, coming and going to a market town keeps one down to a walking pace. On the particular occasion when the author and artist passed this way, all the animals bought and sold that day at the cattle fair of Quill an seemed to be coming from the town. The little men who had them in tow were invariably good-natured, but everybody had a hard time in preventing horses, cows and sheep from bolting and dogs from getting run over. Finally we arrived; and a more well-appreciated haven we have never found. The town itself is quaint, picturesque and quite different from the tiny bourgs of the Pyrenees. It is in fact quite a city in miniature. Though Quillan is almost a metropolis, everybody goes to bed by ten o'clock, when the lights of the cafés go out, leaving the stranger to stroll by the river and watch the moon rise over the Aude with the ever present curtain of the Pyrenees looming in the distance. It is all very peaceful and romantic, for which reason it may be presumed one comes to such a little old-world corner of Europe. And yet Quillan is a gay, live, little town, though it has not much in the way of sights to attract one. Still it is a delightful idling-place, and a good point from which to reach the château of Puylaurens out on the Perpignan road.  CHÂTEAU DE PUYLAURENS Puylaurens has as eerie a site as any combination of walls and roofs that one has ever seen. It perches high on a peak overlooking the valley of the Boulzane; and for seven centuries has looked down on the comings and goings of legions of men, women and children, and beasts of burden that bring up supplies to this sky-scraping height. To-day the château well deserves the name of ruin, but if it were not a ruin, and was inhabited, as it was centuries ago, no one would be content with any means of arriving at its porte-cochère but a funiculaire or an express elevator. The roads about Quillan present some of the most remarkable and stiffest grades one will find in the Pyrenees. The automobilist doesn't fear mountain roads as a usual thing. They are frequently much better graded than the sudden unexpected inclines with which one meets very often in a comparatively flat country; nevertheless there is a ten kilometre hairpin hill to climb out of Quillan on the road to Axat which will try the hauling powers of any automobile yet put on the road, and the patience of the most dawdling traveller who lingers by the way. It is the quick turns, the lacets, the "hairpins," that make it difficult and dangerous, whether one goes up or down; and, when it is stated that slow-moving oxen, two abreast, and often four to a cart, are met with at every turn, hauling hundred-foot logs down the mountain, the real danger may well be conceived. Axat, the gateway to the Haute-Vallée is a dozen or more kilometres above Quillan, through the marvellous Gorges de Pierre Lys. This is a canyon which rivals description. The magnificent roadway which runs close up under the haunches of the towering rocks beside the river Aude is a work originally undertaken in the eighteenth century by the Abbé Felix Arnaud, Curé of St. Martin-Lys, a tiny village which one passes en route. The Abbé Arnaud who planned to cut this remarkable bit of roadway through the Gorges du Pierre-Lys, formerly a mere trail along which only smugglers, brigands and army deserters had hitherto dared penetrate, and who to-day has the distinction of a statue in the Place at Quillan, was certainly a good engineer. It is to be presumed he was as good a churchman. The Aude flows boldly down between two great beaks of mountains, and here, overhanging the torrent, the gentle abbé planned that a great roadway should be cut, by the frequent aid of tunnels and galleries and "corniches." And it was cut — as it was planned — in a most masterful manner. One of the rock-cut tunnels is called the "Trou du Curé," and above its portal are graven the following lines: — "Arrête,

voyageurs!

Le Maitre des humains A fait descendre ici la force et la lumière. II a dit au Pasteur: Accomplis mon dessein, Et le Pasteur des monts a brisk la barrière." Surely this is a more noble monument to the Abbé Arnaud than that in marble at Quillan. The actual "Gorge" is not more than fifteen hundred metres in length, but even this impresses itself more profoundly by reason of the great height of the rock walls on either side of the gushing river. At Saint Martin-Lys, midway between Quillan and Axat, is the church where the Abbé Arnaud served a long and useful life as the pastor of his mountain flock. Axat, at the upper end of the Gorge, will become a mountain summer resort of the very first rank if a boom ever strikes it; but at present it is simply a delightful little, unspoiled Pyrenean town, where one eats brook trout and ortolans in the dainty little Hotel Saurel-Labat, and is lulled to sleep by the purling waters of the Aude directly beneath his windows. This quiet little town has a population of three hundred, and is blessed with an electric supply so abundant and so cheap, apparently, that the good lady who runs the all-satisfying little hotel does not think it worth while to turn off the lamps even in the daytime. This is not remarkable when one considers that the electricity is a home-made product of the power of the swift flowing Aude, which rushes by Axat's dooryards at five kilometres an hour. Two kilometres above the town are the Gorges de St. Georges, also with a superb roadway burrowed out of the rock. Here is the gigantic usine-hydro-électrique of 6,000 horsepower obtained from a three-hundred-foot fall of water. That such things could be, here in this unheard of little corner of the Pyrenees, is far from the minds of most European travellers who know only the falls of the Rhine at Schaffhausen. Axat has a ruined château on the height above the town which is a wonderful ruin although it has no recorded history. To imagine its romance, however, is not a difficult procedure if you know the Pyrenees and their history. Its attractions are indeed many; but it would be a paradise for artists who did not want to go far from their inn to search their subjects. There are in addition a quaint old thirteenth-century church, a magnificently arched stone bridge, and innumerable twisting vaulted passages high aloft near the château.  AXÂT Away above Axat is the plateau region known as the Capcir, thought to be the ancient bed of a mountain lake. It is closed on all sides by a great fringe of mountains, and is comparatively thickly inhabited because of its particularly good pasture lands; and has the reputation of being the coldest inhabited region in France, though it may well divide this honour with the Alpine valleys of the Tarentaise in Savoie. One passes from the Capcir into the Cerdagne lying to the eastward by the Col de Castelllon. |