| THE EMPIRE OF

AROOSTOOK THE size and

situation and resources of Aroostook county are such that our interest

in it is

very great. It borders the Dominion for more miles than any other

county. For a

considerable part of that distance the boundary is a river. At the

point where

the St. John joins the Woolastaquaguam the elevation is about 75o feet.

From

this point to the state boundary it is 158 miles, and the stream is

navigable

for its whole length in Maine, of course to vessels of moderate size.

To this

gradual fall we owe the prominence of canoeing in Maine. This great

county is

most attractive to hunters and fishermen, because large game is still

to be

had. The moose, the king of the forest, of course stands in a class by

himself.

Bear are not very rare. The fishing is still good. Aroostook grain

fields are

in places extensive, since this is one of the regions in the east where

grain

can still be raised advantageously. The potato, while a very important

crop, is

not the only one, as the ordinary newspaper paragraph would lead us to

suppose.

The generally

moderate changes in elevation have favored the construction of good

roads.

Ridges of gravel and sand, so called "horsebacks," which mark the

glacial drift, furnish an inexhaustible store of road material. The county

benefits

from the military road put through by the nation from Bangor to Houlton

and

completed in 1830. After the boundary disputes which threatened war

were

settled in 1842, there was a rapid influx of farmers. The size of

this

county is impressed upon us when we find it is surveyed into 181

townships. It

is, therefore, not without reason that we speak of this region as an

empire.

Whether this beautiful county will soon be more highly appreciated we

do not

know. We do feel certain that efforts such as were made by the state

many years

ago in bringing over Swedes, might be rewarded by a large accession to

the

amount of population. Meanwhile the beauty of the streams and orchards

is ours

to enjoy. The county is

one

of large farms, and strong, self-reliant men. They are able to develop

their

empire, but it will be many years before they can utilize all parts of

it. But before the

beautiful aspects of the county can be fully recorded it will be

necessary to

thread its streams and woodland paths for many thousands of miles. The

grandeur

and desolation of some of the forests is more appealing than any other

aspect

of Maine. Aroostook is lacking a poet, and the same may be said of many

other

parts of our country. Had Scott woven the names of Maine streams and

mountains

into his novels a succession of visitors would have thought the scenery

remarkable. Of our scenery, like our other possessions, it is true that

we wait

for the glamour of a great name before we are awakened to admire. VIEW POINTS IN

MAINE MANY extensive

and

entrancing views may be had in Maine. As a rule, they are not suitable

for

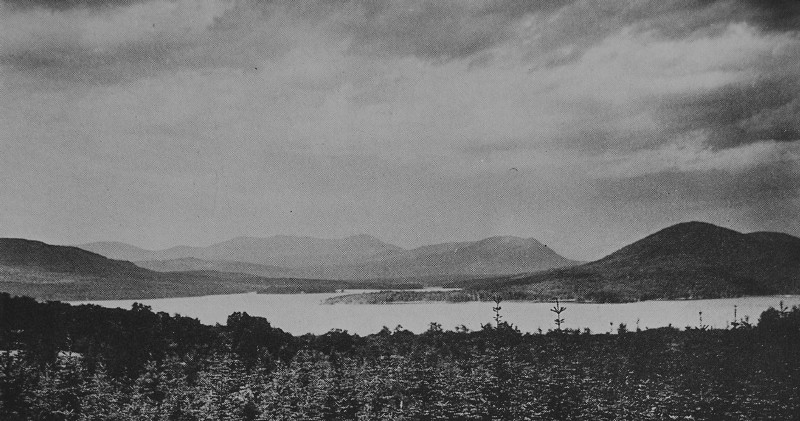

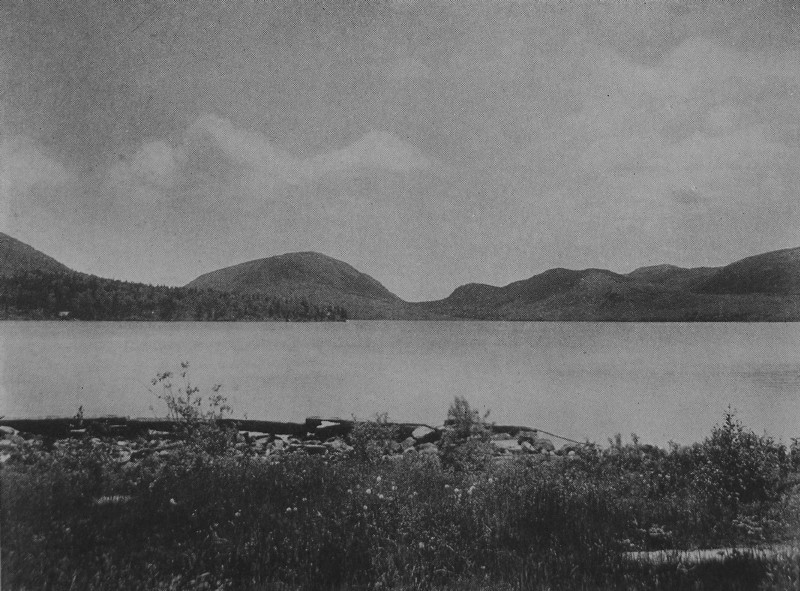

pictures, but it seems important to record some of them. The view of Moosehead Lake, looking either north or south or west from Mount Kineo, is perhaps superior to any other large lake view to be had anywhere in our country. This is especially true on a day with fine clouds. The islands, some merely rocks and others hundreds of acres in extent; the countless little bays; the wonderful mountain outlines against the sky; the magnificence of clouds reflected on a quiet day in the bay, — make up a total aspect of grandeur which leaves little to be desired. OLD YORK JAIL Views only

slightly

less attractive are to be had from Squaw Mountain, from the Spencer

Mountains,

and from other elevated points about the lake. From the top of

Mount Katahdin there is a tumbled mass of hills stretching away into a

dim

haze. The water prospects nearby, from this elevation, are not so

extensive.

Chimney Pond, lying almost beneath one, gives its basin the appearance

of a crater.

The view from

those

Maine mountains which are really a part of the White Mountain range is

often

more attractive than New Hampshire mountain views. We have

mentioned

the unrivalled beauty of the scenes both seaward and landward from

Mount

Megunticook, and the superb view of Kezar Pond and the White Mountains

as seen

from Lovell. The outlook

from

the mountains near Weld is magnificent. In the south of

the

state, Agamenticus gives both sea and mountain views, with agricultural

valleys

in the immediate foreground. With the

completion

of the road to the summit of Green Mountain the finest outlook on the

coast of

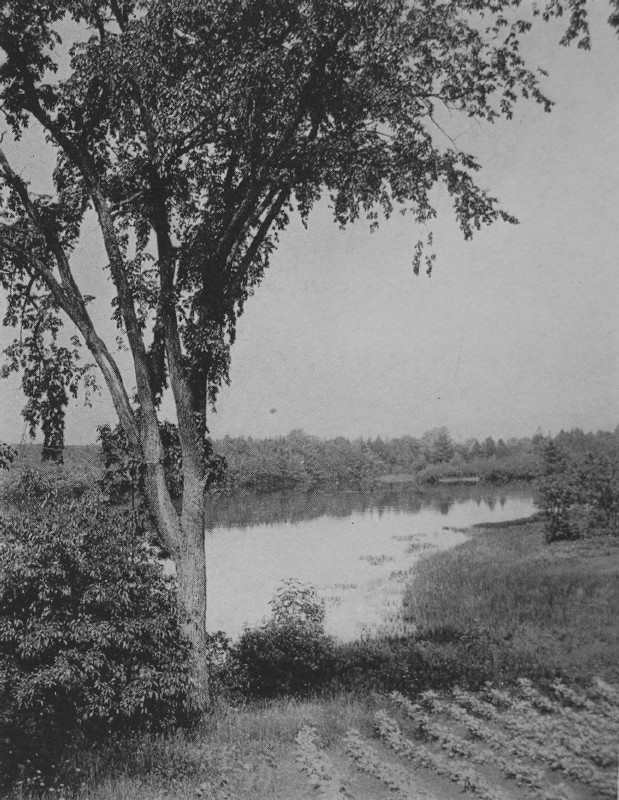

Maine will be made convenient. About most of

the

larger lakes like those of Rangeley, Sebago, Grand Lake near Princeton

and the

Belgrade Lakes, there are view-points of great interest. In fact,

Rangeley and

the Belgrade Lakes, viewed from the west in the afternoon, are among

the most

satisfactory visions vouchsafed to us mere mortals. The most

attractive

river view we have seen in this country, aside from that of the

highlands of

the Hudson, opens to us as we ascend the Penobscot. The

historically

famous view of Casco Bay, already referred to, should not lead us to

forget

various view-points of the harbor of Boothbay, of Merrymeeting Bay, and

Passamaquoddy Bay. It would be too

long a story to enumerate the more intimate views obtained from minor

elevations. The hills about the Cobbosseecontee Lake, while not very

lofty,

afford delightful prospects. A beautiful agricultural region may be

seen from

Allen's Hill in Manchester. In the course

of

this setting forth of pictures there are numerous other prospects which

are

entitled according to their location. Among the minor

and

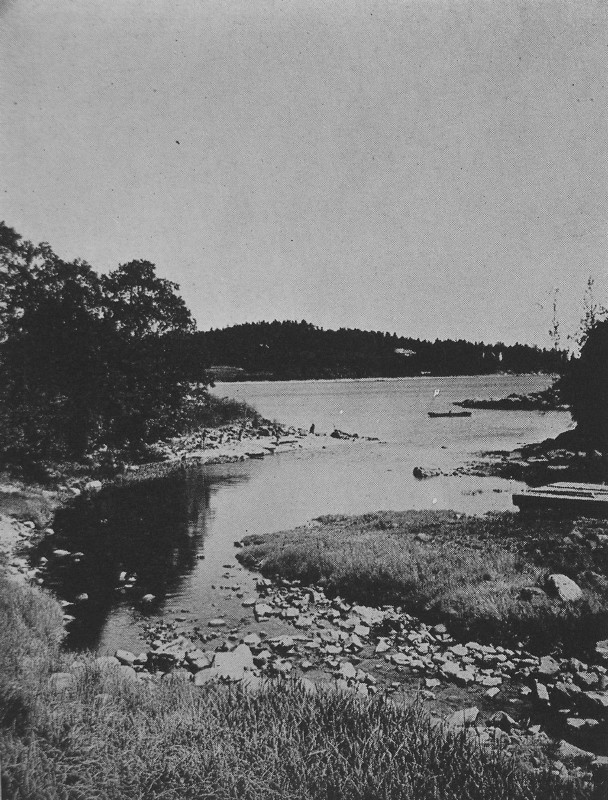

narrower outlooks we may mention those to be had at the Sheepscot

River, of

Damariscotta River, and of the Saco, both in its meadow reaches, and in

its

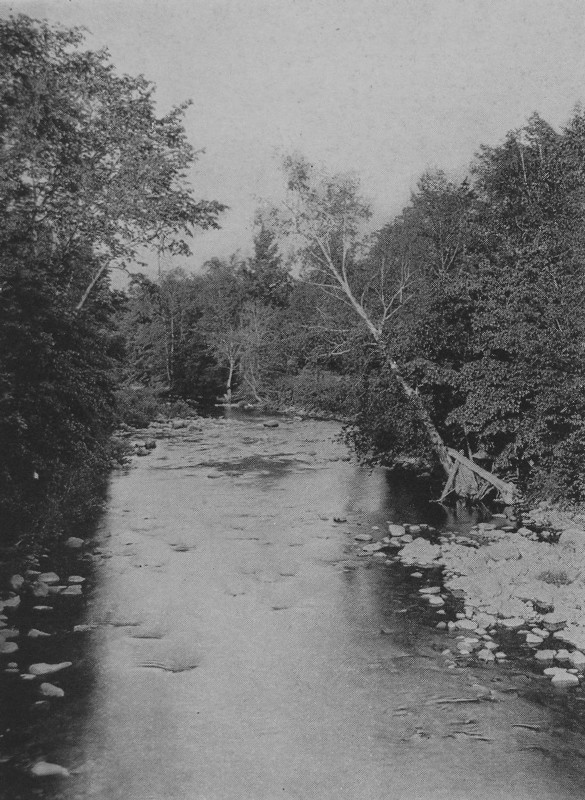

bolder course through the hills of Hiram. The

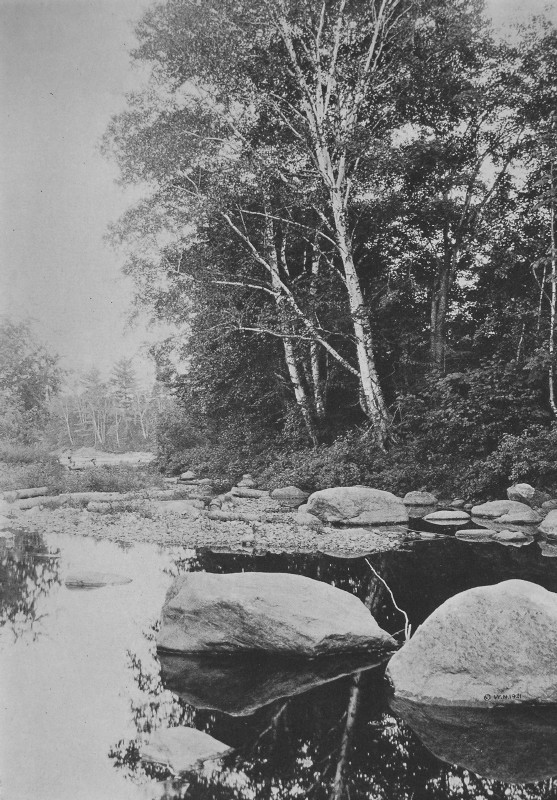

Pisquataquis

River in the county of that name, the Mattawamkeag in Aroostook county

and

Washington county, and Machias River in the latter county, all abound

in

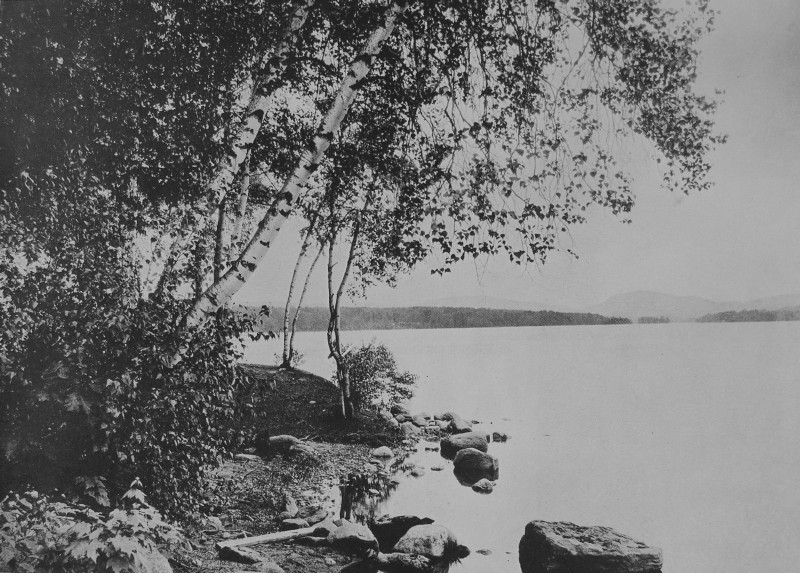

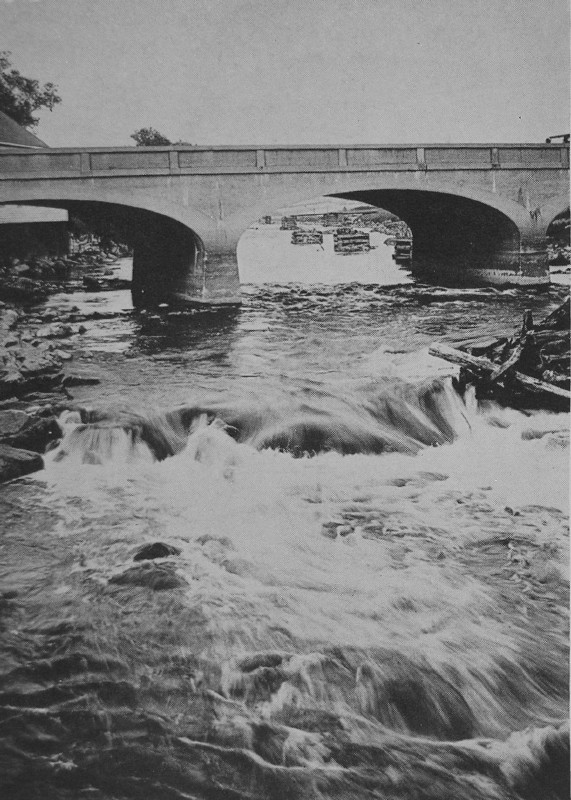

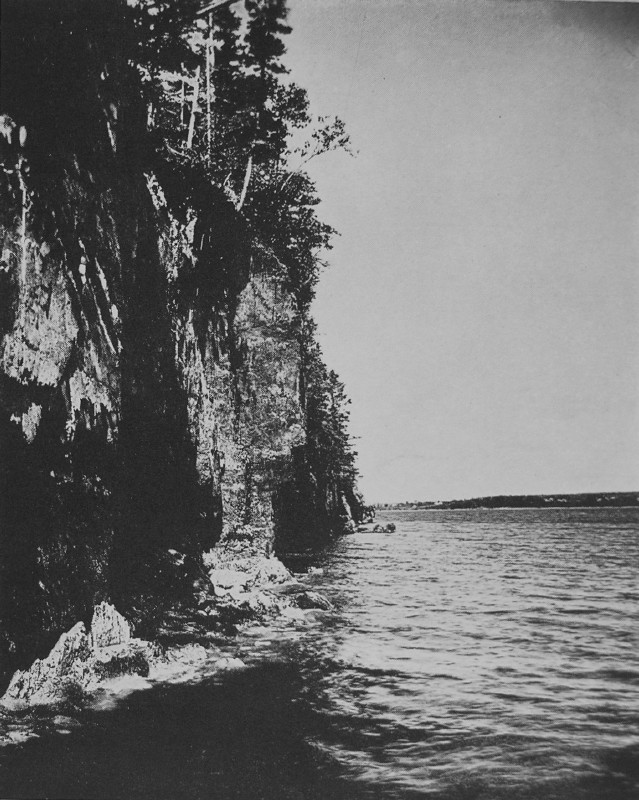

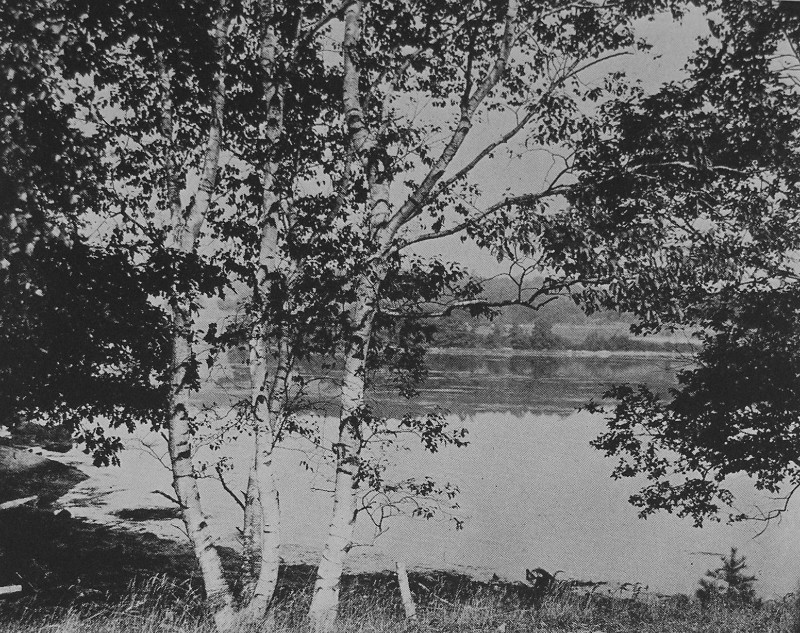

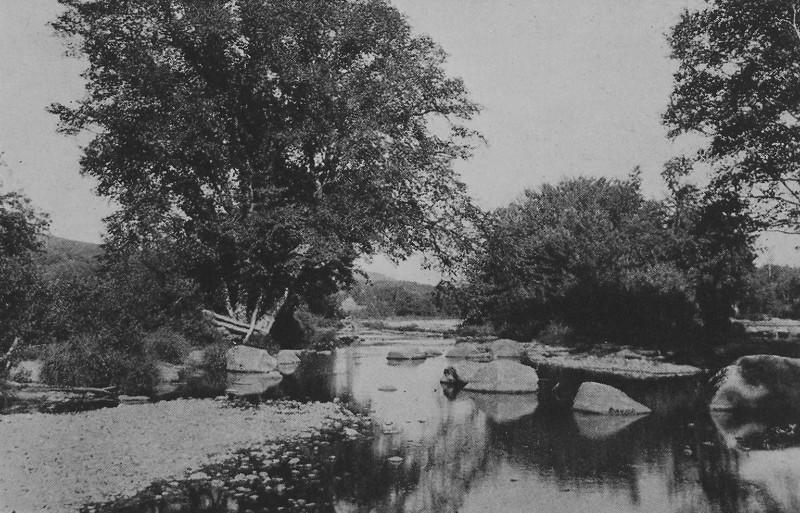

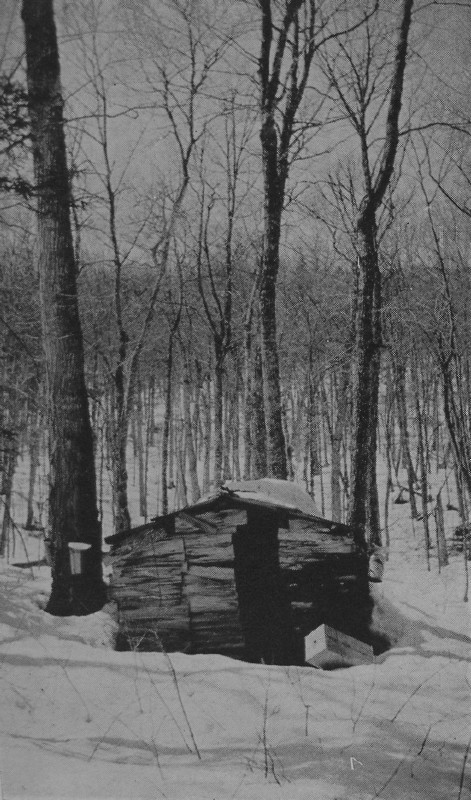

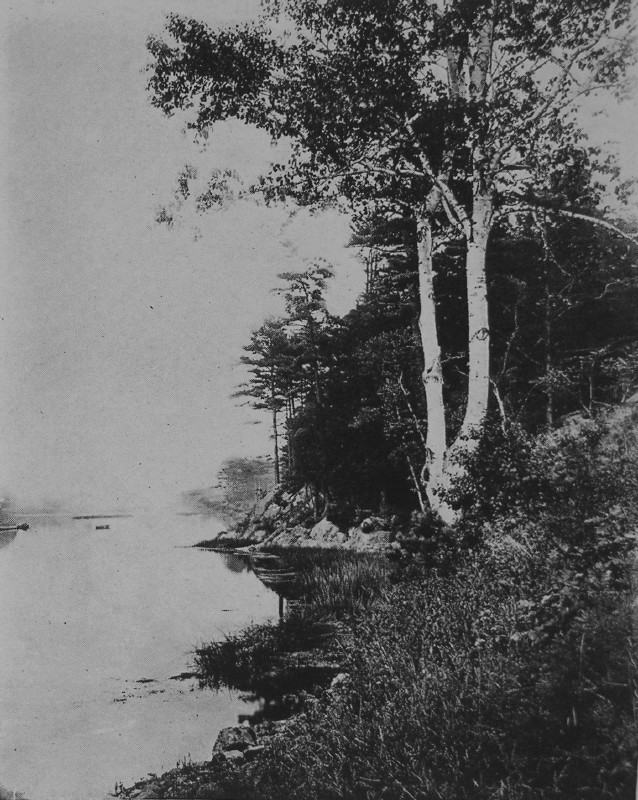

pleasant prospects. The finest agricultural districts, being in towns with no great contrast in elevation, are of course not notable for picturesqueness.  ELMO'ER CREST - SURRY  PLEASANT RIVER  COBBOSEECONTEE HAZE - WINTHROP  A MANCHESTER WOOD  A BELGRADE STREAM  A LITTLE MAINE RIVER  LAVENDER BLOSSOMS - PITTSFIELD  A FEATHERED ELM - BLUE HILL  A WASHINGTON COUNTY SHORE - DENNYSVILLE  WILSON POND OVER EVERGREENS - GREENVILLE  MOUNT GREEN - MOUNT DESERT  AT MINGO POINT - RANGELEY LAKE  THE TUMBLING RIVER - EAST MACHIAS  MOUNT DESERT CLIFFS In such

districts

we must be content with a little turn of the brook shaded by elms or

birches.

This is the sort of scenery that is found almost everywhere, and is

best fitted

to soothe the heart of man. It is the near and dear and familiar

prospect. It is

the view to which children are bred, like the homely scenes of England.

We

could find Maine people in any one of our states who remember with

loyal

affection the little brook where they played as children. They sat on

the roots

of an old maple, and watched the trout, as large as young whales,

scooting from

hiding-place to hiding-place. The old barway, flanked on the one side

by a

birch and on the other by a pine, and leading to the pasture lane, that

was

bordered by wild-apple trees, is a sweet recollection. In Nebraska, in

California, they remember those childhood surroundings, beautiful in

themselves

and more beautiful in the soft haze of forty years ago. The old apple tree on whose branch they sat to read tales of Indians or knights is a better tree than the most stately monarch of the forest. We come upon an old farm whose owner returns for summers of longer and longer duration. There, with merciful surgery and sustaining braces he tries to preserve the old apple tree, as it is perhaps the only living companion of his boyhood. TRUTH AND BEAUTY SAY what we

will of

the pitilessness of nature, we do not find that the pitiless mood is

habitual.

Usually she is tender with us, confiding, and affectionate. She humors

our

whims and allows us to rest or play or think among the charming seats

which she

affords. Even the ledges in the pastures seem friendly. We hear much of

the

marble heart. We are not so sure that the sermon in stones is a mere

poetic

figure. Most of the soil seems to be disintegrated rock, and the spirit

of the

lily is a daughter of the granite. We insist on our relationship to

dear old

mother earth. Perhaps she understands us better than we know. Certainly

she is

honest with us. There is an unquenchable and eternal effort in nature

to

beautify everything. More and more ugly forms are passing out, while

the more

graceful shapes establish themselves. Consider the grewsome assemblage

in the

animal world during the early geologic period as compared to the

gracefulness

of the beasts we have today. The vast, shapeless, slimy monsters remain

only as

fossils. Now, if you roam the forests, you see instead the graceful

head and

limpid eyes of the deer peering at you through the glades. Instead of

the

flying reptiles we have the phoebe and the robin. More and more the

coarser

forms pass away. Hidden graces take shape from the rock and from the

most

unpromising and inert material, life and beauty spring forth to give us

a

wonderfully attractive world. In this sense there is a beauty spot

everywhere.

Nature is never tame. She never bores us. Does she ever lay her colors

twice

alike in the sky? How many forms of clouds are there? Did anyone ever

count

them all? Is there any limit to the possible shapes of orchids Or

irises?

Whether we coax nature along or leave her in her wild state, she always

feeds

us with new suggestions, new form, new colors. Tennyson saw a universe

in a

single flower. By rigorous analysis, all poetry aside, we may find the

universe

in an atom. The seeker after truth, when he takes this name, seems to pose as a sort of twentieth century knight, and to imply that he has before him a heroic and difficult quest. But is not truth nearer than that? Is not the absolute integrity of the universe witnessed by the subtle but uniform cohesion of particles too small for us to see even with a microscope? Moses did not invent the ten commandments, neither did He who walked Galilean fields first utter the beatitudes. They spoke in better form what had been uttered in a fragmentary way before. They crowned the truth and the beauty which is in the rocks, the soil, the sea, and the sky. They did not recognize any discord between the lily and the law. Their effort was to arouse us from dullness and to face the facts. There is nothing new either in the moral or physical universe. All is mere discovery, emphasis, application, and illustration. All is a process, conscious or otherwise, of getting into harmony with the beauty that is everywhere trying to manifest itself, with the music that has always been in the air in a splendid overtone, never flattened, never harsh. We go about the world holding a mirror up to nature. We discover nothing new, but we are seeing it for the first time and therefore, as far as we are concerned, it is a discovery. A LORD MAYOR'S PROCESSION, AGAMENTICUS HIDDEN THINGS

COMING TO LIGHT

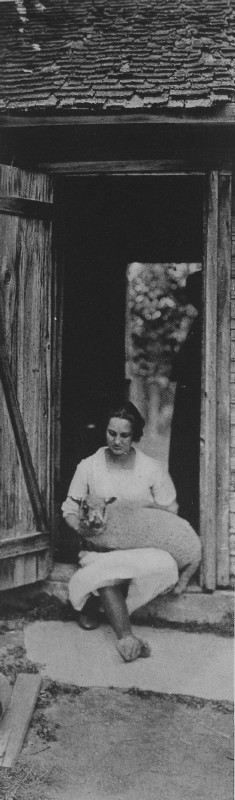

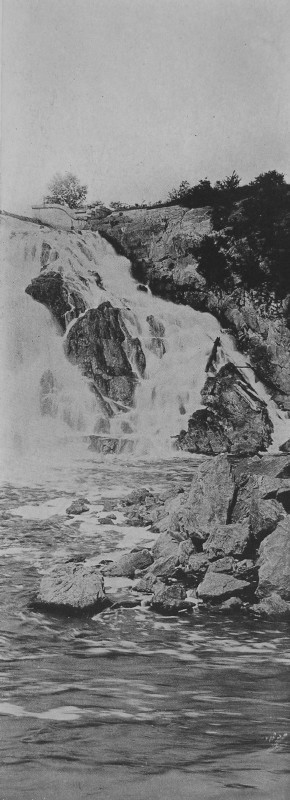

WE may define human progress as a reverential effort to put together the hints of things that we do not see. We are engaged almost altogether in handling forces which, in their ultimate analysis, are subtle and invisible. We have not yet been able to get back to ultimate things. Every generation finds another subdivision in what was before supposed to be the primary form. This is all a most fascinating occupation. Every honest and active man helps. And every living thing helps. The bec does his part. His seed-carrying is more important than his honey-gathering. The bird does its part. The worms are doing their part. They have wrought a chemical change in the soil of the earth. The sunshine creates the green that makes vegetation possible. The wind does its work, and the seeds have their wings arranged to take advantage of it. The freshets carry vegetation across oceans. Salt keeps the world from congealing and keeps it Sweet. We talk about the living and the dead; but everything is alive, throbbing and thrilling, even the particles of the rock. Since there is a world of beauty in what we can see, we infer beauty as existent everywhere. We see it under the microscope and with a telescope. We see it forming on the window-pane and in the crystals of the rocks as well as blazing from the stars.  THE PET LAMB - PRENTISS  FALLS AT ELLSWORTH  THE BACK FIELD ROAD - ALNA  SALT COVE BIRCHES - DAMARISCOTTA  AN ELM FESTOON - PITTSFIELD  A SALT COVE - HANCOCK  AUTUMN AT BETHEL  THE GRACE OF THE STREAM - BETHEL All the

ugliness we

have so far discovered we have found in the trail of men, who, perhaps,

thought

they were doing a good thing. Our commonest mistake has been our

failure to

follow the leading of nature as to what is beautiful. Hence our

unsightly

constructions, our poles and wires, and what not. Gradually it is being

found

that we can do in a beautiful way what we once did in an ugly way. The theologian

has

also been afraid of nature. He thought the devil was in it. He has now

learned

that there is one God in all, and over all, and through all. He knows

now that

all ground is holy ground. He knows now that the mightiest gift ever

contributed to religious truth is the splendid unrolling of evolution.

We all

know now that the change of a letter in some old manuscript need not

upset the

serenity of those who seek the beautiful and the good. The age has

done

much to lessen the conceit of specialists, each of whom used to suppose

that

his own line was the life-line of the world. We know now that no one

branch of

knowledge, and especially no one person, can unveil very much of that

eternal

truth which is beauty. Thus every great poet now respects the toilers

in

chemistry, and they in turn respect moral mysteries. Just so that we

honestly

try to find out about the truth of things, we are all working on the

same job.

There is nothing little unless we choose to make it so. There is

nothing big

except as we offer it to be put in its place as an indispensable part

of a symmetrical

whole. The only real enemy is ignorance, if we spread that term to mean, as it fairly does, the selfishness born out of ignorance.

WHATEVER is nearest to us, seeming very important, is therefore important so far as its influence on us is concerned. Moralists and others have objected to the littleness of men who thought their private matters of superlative account. There is, however, a way in which this natural and universal tendency may be counted an advantage. If our eyes were so made as to show near things small and distant things large, it is a question whether we should derive any advantage from obtaining this more correct optical view. Since we have to do most with the things that are near it may be better that they look large to us. If we only select from these near things those which have an absolute importance, our vision will not distort the truth. For instance, an apple blossom hangs over our head. We take it into our hand and look critically at the petals. It is as beautiful as we can conceive anything to be, and, merely because it is near us, we should not, in our broader modern philosophy, think it of small account. The blossom is near us so that we may examine it in detail. It is a flowering of truth, showing in epitome a kind of essence of the universe. A farmer's wife, having this blossom by her window, really dwells with a superlative thing. There are other growths in the little house-garden which, so far as we know, are just as exquisite as anything God has made. We need not go to Burbank, or to those who cunningly produce hybrids, to obtain anything more perfect. We are, as a matter of fact, living in a world where some things have reached perfection. Certain flowers at their best, a human being of the highest type, a summer sky, — all these and many other products may be counted the acme and crown of creative effort. We cannot ask evolution to do anything more. By the examination of various other things that grow, or that men make, it is easy to see that the ideal has not been reached. But we ought not to forget the distinction that has been achieved in the world up to date. Is it not much to say and more to feel that some forms and some colors and some characters are wholly satisfactory? Among so many things that we have yet to do, human nature takes comfort in feeling that some processes of creation are finished. They are exquisite. We cannot ask or imagine anything better. It is by dwelling on these finished things that we gain courage to improve other things. The perfect things are to rest us and lift us and make us capable of going on. What courage it ought to give to an artist or a theologian that he can discover something with which no fault can be found. This perfection of form or function is, of course, seen more generally among elemental things, such as a drop of water or those minuter shapes which must be examined microscopically. Thus the snowflake, the petal, and the crystal have reached their climax. This achievement ought to be regarded as a prophecy. We ought to understand that this process is inherent in the scheme of nature. We ought also to know that there is in man an impulse, call it what you will, that leads toward ideals. There is no more danger 0f the death of an ideal than there is of the death of a crystal. A crystal may melt and an ideal may disappear from one mind or from many; but the source of the ideal lies in unchanging laws, and it will come into being again. As the clover and the herd's-grass has spread from America over Europe, the forms of flowers are sure to follow. The channels of information increase. The paths through which perfection is nourished and made what it is cannot be permanently clogged. The truly scientific mind is a mind full of confidence in the future. The unveiling of what nature is doing breeds confidence that she has no notion of quitting work. She is going on. FORT HALIFAX - WINSLOW We suppose the

atom, in a huge, prehistoric lizard, to have been precisely like what

an atom

is today. That is, perfection always existed in the primary forms of

matter. It

is in the combination of these primary forms that improvement is going

on and

the sense of beauty is being developed. Obviously, the greater number

of

combinations required in any finished product, the more difficult it is

to

reach perfection. It is precisely here that evolution is working.

Perfection of

adaptation is a process, and a process apparently urged by some

immortal

impetus. There seems to be a Thought behind all. Were it not so, there

is no

reason why horrific creatures, like magnified beetles, should not have

the

intelligence of man. In the scheme of things, the finest intelligence

occurs

with the best forms. The fly is kept down while the eagle becomes

large. Even

in small things, the process of transformation into beauty is going on.

In all

large things in the vegetable world, and mostly in the animal world,

the shapes

that now exist are beautiful. There are those who fear that perfect forms cannot be permanently cept, since they see how apparently difficult and long is the process by which they have been brought into being. But we should not forget that the impetus which brought forth these forms is in no degree lessened. Every successful combination seems to make more feasible still better combinations. We believe in the Thought and the Power that is bringing this about. The apparent immortality of subtle forces, such as we discover in radium, ought to make it easy for us to understand that this radio-activity is not an exceptional case. Everywhere are agencies of all sorts, immortal in their tendencies. That is to say, matter has a tendency which seems to be a part of itself. You cannot imagine matter without its attractions and repulsions. If gravity and cohesion and the various chemical affinities are discovered anywhere, it is always in connection with forms of matter, just as character is a part of a man. That is to say, we cannot separate matter from its tendencies or its passions, if you so choose to name them. It is because we can depend upon these steady aims or purposes in atoms and molecules that we see hope for a world of ultimate beauty. Somehow, everybody believes in matter. It is a basis of faith on which all men can get together. But the features of matter which impel it this way and that, that blend two particles or three as one, that make gold and air and diamond, these features may be thought of as the soul of matter. Its affinities cannot be separated from it. This is the most hopeful thing in our day. It means that whatever has produced the highest success, whatever has made possible a Plato, is an urge that never ceases. It means that if civilization goes down it will go up again. It means that the most beautiful imaginings of a Greek artist will be surpassed. It is idle to presume that since we have waited a long time we must wait always for this thing to happen. If beauty is in the soul of matter, and is struggling to express itself, the result is certain. The common phrase that what goes up must come down, is borne out of pessimism, and is unscientific. The fear of death and disintegration is not borne out by the eternal impulses in matter. Creations continue, and must continue. Beauty rises higher after every destruction. GARRISON-HOUSE AT YORK, BUILT ABOUT 1645 We have no

fears

for the ultimate future. If Maine is now a shore fitted to enthrall our

imagination

and delight our senses, the fact is merely a proof that the yearning,

if we may

so call it, in matter and man, rests on ultimate things. It is a proof

that

forms of grandeur of a nobler sort must in every age continue to

develop, and

the appreciation of man must continue in a similar development. Wells, in his Outline, can see no progress except in a fidelity, growing in man, to the truth. This, at last, is religion. It is also, science. Make the most of it. THE FUTURE OF

MAINE MAINE, considered as a national asset, is not occupying the position which its scenery, its size, and its resources deserve. Settled first and admired most by the discoverers, it is being developed last. Some Maine people consider the state to be of importance for two things only, in a permanent way. These are its water powers and its tourist attractions. We are far from agreeing with this judgment. We believe that Maine as a source of building material, aside from its forests, must count very heavily in the future. Further, we think that in time its agricultural resources must prove of great value. It will not always be true, as it is now, that farming is the last resort. The extent and variety of Maine's soil will not permit it to be ignored. The lumber resources of this state will of course in time be subordinated to its other features, but by conservation those resources will always be a large asset. HIGH STREET, WISCASSET The attractions of Maine as a residence must eventually appeal to many millions of Americans, as well as to persons of other lands. This remark holds true not only of the summer months. In these days almost every one has a vacation. The people of Maine, by taking their vacations in the winter and going south, will be far better off than those who live most of the year in the south, and can get only a month or two in Maine. The Maine winter is not disagreeable before the month of February, and even then there are many who enjoy it, so much so that more and more Maine is being visited in the winter by guests who want to know what a real winter is. Those who have the leisure and the means to make a southern journey for a month or so in the winter will find Maine a climate more attractive in some particulars than any other that we know. The coast of Maine is the only section of the entire Americas except western Washington that is comfortably cool in the summer. The fog which often visits the coast in this season is a great joy to persons who have escaped the welter of the cities. It always tempers and cools the air, affording the humidity without heat which is a natural craving in the summer. Every foggy day is a joy and most bright days are breezy. COMMENT ON LINE

DRAWINGS IN order to

enrich

this volume as much as possible, we have added thirty-two sketches in

the text

pages. Sir William Pepperell (house p. 28) commanded Maine troops at

the siege

and capture of Louisburg from the French in 1745, on June 15, a notable

date

for Maine since the state — or Dominion of Maine as it was

then — was never

afterwards seriously hindered in its development eastwards. It is hard to

remember that the English were for one hundred fifty years either

actively Or

dormantly hostile to the French in America, and that it was long

doubtful

whether the English civilization would prevail. From the Penobscot

eastward the

country was generally held by the French, and the region from Maine to

the

Penobscot was debatable land. The Indians of this district suffered so

much,

whichever side they favored, that between war and pestilence most of

them were

either destroyed or discouraged, and migrated to the St. Lawrence.

There,

congenial to the French, they were more at ease though they found a

climate

still more rigorous than that they had left. The few

remaining

Indians of Maine, gathered just above Bangor and on Passamaquoddy Bay,

are

wards of the state. Their ancestors were outrageously treated. They

themselves

are with difficulty being brought to understand the independent spirit

of

America. Visits to their homes are glimpses to a life very interesting

to us of

the twentieth century. In the Longfellow house, in the center of Portland, the public possesses a very delightful monument (p. 29), since it was here that from infancy he grew, though horn and living for a few months in another Portland house. Between this public memorial in Portland and the Longfellow house in Cambridge, eventually to come into the hands of the public, or trustees for the public, the nation will have very great and rich memorials of the beloved poet. The Portland house being of brick will he easier to protect from fire, and with care may become a possession for many generations.  THE BATH OF THE WHITE LADIES - DAMARISCOTTA  ANDROSCOGGIN BIRCHES  BANKS OF THE CARRABASSET - KINGFIELD  A DECORATIVE SHORE  OXFORD COUNTY WATERSIDES  THE SUGAR CAMP  TWIN SENTINELS - GERRISH ISLAND The Campus of

Bowdoin College (p. 41) is shown in another of our pictures (p. 144).

Although

Maine had no separate early existence, many of her institutions are

very old,

and Bowdoin has all the storied flavor of an ancient seat of learning

— the

most delightful of human retreats. The old name

for

York was Agamenticus, still retained by the lofty hill behind the town

— the

landmark of southern Maine, and the stream that flows hard by. We

presume this

cut from Drake is taken from a painting. We are very

pleased

to examine it, since it faithfully represents the architecture and

customs of

that period. York just escaped being much more important than it is.

Only its

location prevented the choice of it as the capital, and for long it was

the

most important place in the state. The sort of dwelling shown in the

distance

on the left is very rare nowadays, so much so that many traveled

Americans have

never seen a specimen. Probably many hundreds of such seventeenth

century

houses have been torn down. In a generation those that remain will be

very

highly cherished. The York

garrison

(p. 271), represents the second period of architecture such as still

exists, especially

in Connecticut. The Tristram Perkins house was a Kennebunkport landmark, and is most pleasing from its fine lean-to. It is dwellings like this that give character to a town. The fashion is happily revived and could scarcely be bettered. SOME OF THE

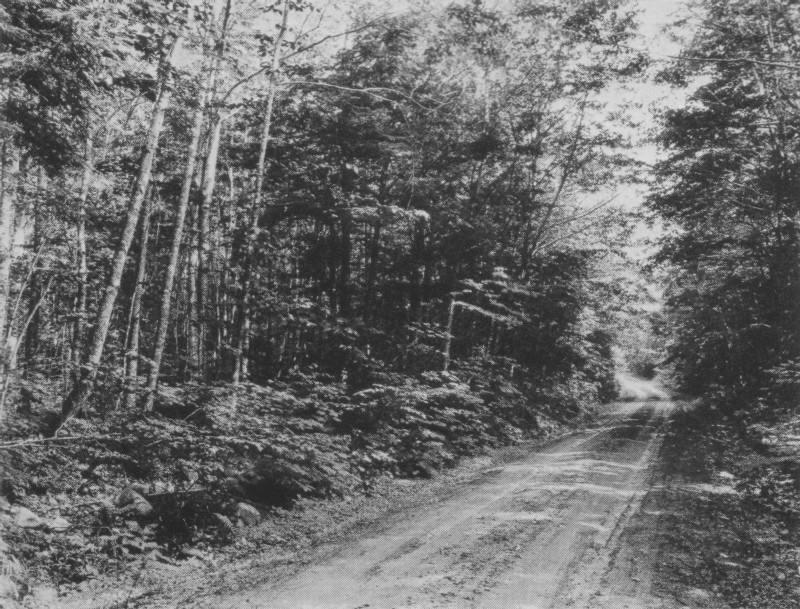

PICTURES IN DETAIL "ROUNDING the

Cliff" (p. 11) is one of the most charming spots we have found in

Maine.

It is admirably adapted in its immediate surroundings and its

accessibility for

a summer home, and if a residence here were continued for ten months in

a year

each of those months would have its special attraction. The spot is a

little

removed from the highway, perhaps forty rods, and it was, we presume,

the site

of an ancient dam which has almost entirely disappeared. There is a

fine, bold

vertical stratum of rock on the left, of warm, rich, brown color. The

outlook

in three directions is excellent. No lovelier water-view, no better

foundation,

no region more inviting for wood-paths comes now to our recollection.

There are

no dwellings near this spot. A quaint old

bridge

at New Vineyard, a spreading stream, and a substantial, rambling old

dwelling

make up a composition very satisfactory to the eye and the heart. We

would say

that the spot was susceptible of being beautified to a very great

degree (p.

159). In "Danville

Banks" (p. 37) we find a surprisingly pretty shore, just out of

Lewiston

and Auburn and on the Poland road. This region has not been thought of

as one

of particular attraction. The shore, however, is as good as one could

wish. "A Maine Coast

Sky" (p. 47) is a happy combination got by the author many years ago,

it

being one of the few pictures that are not new. The curdled sky is

always

wonderful, as it often suggests outspread wings. The attractions of the

sky in

Maine are often greater than those of the landscapes, in the east. When

both

are good the heart of man can ask little more. In "A Woolwich Homestead" (p. 49) is a type of the earliest substantial houses in Maine. A well-sweep still appears. Woolwich was settled almost among the first towns of the state. It was a very extensive town, and counted as a unit with Bath. At the mouth of one of the two principal Maine rivers it was close to the accessible highways of that period. On both banks of the Kennebec from its mouth up for a score or so of miles are found a good number of early dwellings and good farms. The river was the only road at the time. It is highly delightful in these days of flying machines to discover that the Pilgrim Colony arranged for an express shallop, to make the run from Cushnoc, now Augusta, passing all the shore towns, to Falmouth, or what is now practically speaking, Portland, in twenty-four hours. This was fast going at that time. The Pilgrims had good muscle as well as good consciences. They were not anaemic religionists. Like all men who have a living to make they became sturdy, and like all men who establish trade relations intended to continue, they were fair dealers. There is no finer district either for agriculture, climate, a choice of water-routes, and attractive scenery than that at the mouth of the Kennebec. This has been learned by those who have developed Squirrel Island, Popham Beach and the other attractive sea resorts hereabouts. A READFIELD HOMESTEAD In the "Old

Dennett House" (p. 58) we have a delightful reminder of the seventeenth

century. In that time Eliot was a part of Kittery. The entire district

around

the mouth of the Piscataqua River was settled first after Plymouth in

New

England. Kittery at that time was called Piscataqua. Almost in the same

year

Kittery, York, the Berwicks, Portsmouth, and Dover, were taken up by

our

ancestors. The district of Kittery was most wisely chosen as the site

of a navy

yard, it being one of the best harbors in existence. Incidentally, the

estuary

of the Piscataqua is a region of wonderful attractions to the eye. This

ancient

house has the roof line of that time. It is most happy in a noble tree

placed

properly as a companion. The drive that we see is the private entrance,

so that

the old dwelling stands well back from the main street. We can by no

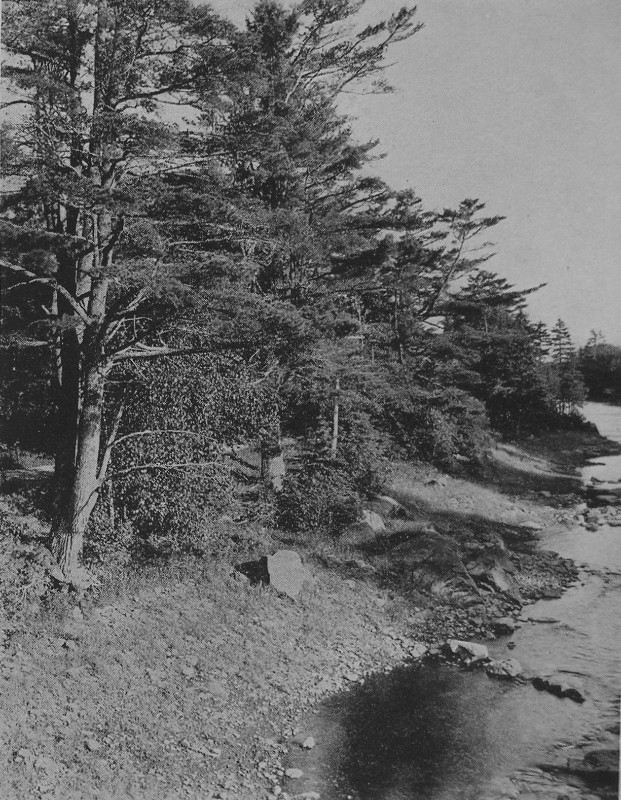

means

attempt to describe all the excursions we have enjoyed in Maine. On the

shore

we think nothing could be finer than the grand cliffs and the salt

spume from

the breakers. In the back reaches behind the islands we believe

ourselves to

have found something even better, in the winding shores, the perfect

cones of

the spruce, and in the miniature harbors beside each one of which we

picture a

perfect home site. In the interior of the state near a cascade on one

of the

subordinate streams, rather than by the roar of a great river fall, we

then

think we have reached an even better location, as a stimulus to the

imagination, a constant challenge to activity. When at last we reach

the

splendid slopes of the loftier elevations in the state, and look out

over

valleys covered by farms and threaded by silver streams, here and there

issuing

from mirrored lakes, we exclaim that here is the best in Maine. Thus it is that what has sometimes been thought a defect of human nature greatly adds to the joy of living. It is a fortunate circumstance that the scene before us seems always to be the best. We can always find something in it of peculiar merit. There is an inexhaustible quality in any landscape. Certain groups of trees, certain curves of the hills and of the shores, certain windings of the road or settings of the cottages, disclose themselves to us from day to day with added charm. It is this capacity for seeing attractions already existing that suggests the capacity for attractions which may be added about the old homestead. The person who loves an old home will often look at it with the view to adding a drive here, a cluster of trees there, a field wall, or some landscape feature that will still further enhance the pleasures of home life. The dwelling itself also may be made more solid or better able to resist the storms. Thus the joy of seeing and planning must enter into every consideration when one has or seeks a home in the country.  CLOUDS OVER DODGE POND - RANGELEY  UNDER A BIRCH BOUGH - HALLOWELL  A POLAND WOOD  AN INLAND LAKE - MOUNT DESERT  HOSMER LAKE - CAMDEN  A LITTLE COVE - MOUNT DESERT  CLIFF OVENS - MOUNT DESERT  AN OXFORD COUNTY STREAM  A COTTAGE IN RANDOLPH  EAGLE LAKE - LAFAYETTE NATIONAL PARK  A WEDDING VEIL - LINCOLN COUNTY  MOUNT KINEO FROM MOOSEHEAD LAKE There is

probably

no pleasure in life, aside from moral aspects, that can equal the

pleasure of

developing a home in the country. The joy consists not altogether in

directing

the work of others. The fullness of delight will not come to any man

until he

takes in his own hand a trowel and lays the foundation stones. Unless

we know

the feel of a spade and a hammer we shall never fully enjoy handling a

pen or a

brush. To see one's own thoughts arise in stone or brick, to see the

approaches

taking form as they did in our dreams, and to observe the increasing

grace of the

curves of elm and birch and balm of Gilead, as those trees increasingly

decorate the home acres, these are joys worth the participation of the

greatest

minds. To arrange one's own garden and to train the vines against the

wall, and

to prune the fruit trees at the back door, to follow at least

occasionally

behind the plow and to see the sod reversed in a long graceful curve,

this is a

necessity to a man who would really understand his relation to the

natural

world. By such participation with the materials of the earth he

enlarges his

range of thought. He multiplies his points of contact, and becomes a

more real

human being. If he adds to or crowns these occupations by founding a

family to

grow up in the country, he has then become a complete man so far as our

limitations will permit. He provides

himself

with baskets and lunches and takes his family or friends up to the

mountain for

a day of berry picking. He goes to the river, and with a chosen

companion

paddles around its curves, or rests in its eddies, or floats on the

little

lake. Fishing for a while, chatting for a while, watching the clouds

and the

hill contours for a while, he returns in the quiet of the evening to

the old

home. Days occupied in the orchard or the woods, where old paths lead,

he joys

in the fellowship of silence and the forest denizens. It is a good

world. Even

in the old cemetery, where the shadows play across his ancestors.

graves, he is

not too sad. He admits the mysteries in life, he meets its pains and

sorrows

like a man, and all in retrospect blends in one picture. He cannot

change it so

far as it is drawn. But he is hopeful that what he has done has not too

much

marred the symmetry of the whole. He is confident that other

generations will

go forward with a surer brush. Life is good. It may be rich. It cannot

be

disastrous, if we move along steadily, as we can. The most beautiful thing on earth is a countryside developed and dwelt in by a kindly, honorable, diligent people. A good neighbor means more in the country than elsewhere. Character shines with a more pleasing luster in the country. There, four or five roads leading here and there in a neighborhood and occupied by dwellings each with its own bass-wood or pine or pear trees, furnish forth a neighborhood adequate for all human events. It is a sufficient scene for Mrs. Wilkins. A well developed neighborhood of this sort supplies the reaction of man to nature so that each appears to the best advantage. We find it difficult to separate Washington from Mt. Vernon. Because the English could not separate him from his home acres they said he was only a country squire. That country squire foundation enabled him to be Washington. The same foundation gave us a Hampden. Putman came up from such a neighborhood, and Cooper, and how many more! But it is not necessary that one's name should appear in any history to establish proof of a successful life. Much that is bitter has been written regarding the inscriptions on grave-stones. No doubt those who carve the stones desire to say something kind. Why should it be otherwise? Are we heartless enough to look for a critical comment on a grave-stone? Why has not some one complained that the patience and the toil and the hopefulness of those who rest in the country churchyard are not more fully recorded above them? Count the stones which they picked, if you can, and the wall which they builded. See their monuments in the solid dams and the barn foundations. See them in the rows of maples and elms and in the old orchards. See them in the eyes of their children of the fourth and fifth generation, those children who have become the leaders in the mighty work of modern America. We reverence any man who has worked long and faithfully, who has believed in his home acres, who has lived with his wife and loved her always, who has brought up children to believe in honor and diligence. He who has done this is better than a genius because he has been the strength of human society. However America may be living today, it rests on a foundation of men who told the truth and ploughed the soil and fought the storms and fell fighting in their tracks. We would trust a calloused hand, with somewhat gnarled fingers, much more readily than the man's hand that has just come from a manicure. The state is built on truth and muscle and hope, not on compliments and cosmetics. THE TRISTAM PERKINS HOUSE A STREET IN UNION At last only that natural beauty is attractive which can be enjoyed by decent people. Those who are not building up the country can neither fully enjoy its scenery, nor have they a right to do so. There cannot possibly be a full response in their natures to the finer and stronger elements of a landscape. Something of the rock, something of the mountain, something of the fullness of the lake waters, must enter into the nature of the man or he cannot see and feel these things properly. He therefore finds when he goes away for the summer his chief enjoyment in the skulking rooms of hotels, in the underworld which supplies his appetites by scoffing the law. No country place is good to him that is without a green table or a red liquid or purple morals. We have heard and seen so much of "going into the country" from those whose only purpose is to make a slimy trail that we turn with joy to the finer and more real things. Life in its larger riches is found under the oak and by the fireside, in the sweet intercourse with sane persons who know how to rest because they know how to work. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS WE are indebted

to

the Maine Publicity Association for the surf scene with the four-masted

schooner and the lighthouse (p. 14). The anemone cave on Ocean Drive,

Bar

Harbor (p. 193) is supplied by the Maine Publicity Association. A

picture of

seagulls (p. 14) from the same source was from McDougall &

Keefe, Boothbay

Harbor. The ski jumper

shows Victor Mortenson of the Nansen Ski Club making a leap of

seventy-six

feet, (p. 36). The attractive

picture of a lonely sail (p. 70) is in Casco Bay. It is supplied by the

Publicity Association. A harbor view

of

Eastport, called "The Tow" (p. 194), shows the lines of smacks being

taken out to sea. Eagle Lake, at

Lafayette National Park, supplied like the above by the Maine Publicity

Association, shows the source of the water supply of Bar Harbor, and

the

mountains are Pemetic, the Bubbles and Sargent (p. 288). The gentlemen

fishing

are on Stony Creek, near South Paris, Maine, (p. 194). Gathering Sap

(p. 18),

the little wood hut where sap is boiled (p. 278), and Going with Daddy

(p. 36),

are supplied from the same source. We presume that

Winter Sports (p. 68) is at Damariscotta. A similar picture was made

there by

Lindsay, of Newcastle. "For the Open

Sea" (p. 24) is also a gift from McDougall & Keefe, Boothbay

Harbor. Labbie's

Studio, of

Wiscasset and Bar Harbor, has also supplied two marines, (pp. 165 and

172). Of the line

drawings, The Pemaquid Block House is by Lindsay, of Newcastle. The

Fort

Western Plan and sketch are supplied by Wm. H. Gannett, a descendent of

Capt.

Winslow, the commander of the old fort. The Capitol is supplied by the

Maine

Publicity Association; Larrabee's Garrison and the York Garrison House

are from

Abbott's "History of Maine," the York Jail sketch was supplied by

that museum, and the Lord Mayor's Procession and the Tristam Perkins

House are

from the volume by Drake, the "Pine Tree Coast." The sketches of

Drake Island at Great Chebeague are by Mr. C. N. Sladen, of

Newtonville. The

other nineteen are from photographs by the author. In general, the

pictures are by the author, and most of them have been made in this

very year

of grace, so that they now appear for the first time.

|

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2008

(Return to Web Text-ures)